Introduction

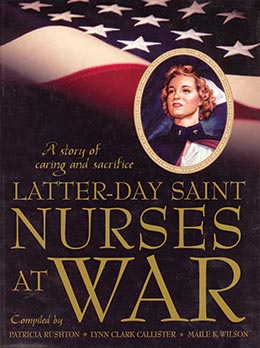

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 1–8.

For centuries, actions associated with caring and sacrifice have been noted in historical accounts. In biblical times, Rebekah provided sustenance by taking water from the well to give to the stranger, Abraham’s servant, and his camels (see Genesis 24:14–21); Jacob worked seven additional years to marry Rachel (see Genesis 29:21–30); Moses advocated for the daughters of Jethro in Midian when he protected their flocks (see Moses 2:16–20); the woman at the Samaritan well provided physical water for Christ, and He offered her living water (see John 4:7–14); Christ healed the blind man at Bethesda (see John 5:5–9); Jesus Christ comforted Martha at the death of Lazarus (see John 11:19–26); and Jesus Christ suffered for mankind in the Garden of Gethsemane (see Luke 22:41–44).

During the nineteenth century, family members and friends cared for those in need, but “nursing” was considered beneath the dignity and social status of all but the lowest working class or prostitutes. For Florence Nightingale to do such menial work would threaten her social standing, but she did it anyway for the benefit of the men she cared for (Helmstadter 2002). During that same century, certain events motivated people to organize acts of caring and sacrifice. These people began to establish standards and values to achieve a common purpose. The people were nurses, the purpose was better patient care, and the setting was the battlefield.

The purpose of this work is to tell the story of Latter-day Saint (LDS) nurses who have served during wartime situations. These nurses have never had the opportunity to tell their story, which has much in common with other stories of nurses who served during a wartime period, but which also demonstrates some unique aspects because of their spiritual and religious perspective.

A Legacy of Caring

Since the work of Florence Nightingale, Dorothea Dix, and Clara Barton, professional nurses have been involved in caring for the sick and wounded during military conflicts. Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) have cared for the sick and wounded since the establishment of this faith in 1830 and have carried out their duties as part of the military since at least World War I. The collection of these accounts is of great benefit to nurse-historians and others studying those who have served during military conflict. Collecting and archiving these accounts is critical because most of the nurses who served in World War I have died and nurses who served during World War II are now in their eighties, some with fading memory and declining health. Many voices are lost each day as this generation passes.

Nurses have much to gain from learning about their rich historical legacy from courageous women and men who served their country during periods of military conflict. Almost all of the nurses who have contributed to this project have made a statement like “I didn’t do anything special. I just did what I had to do.” Their stories, however, illustrate their personal growth, their loyalty to their faith and their country, and their valuable contributions to the progress of the nursing profession and to the health and well-being of others.

We asked LDS nurses to share their wartime experiences through audiotaped interviews, accounts written in personal journals, or retrospective written accounts. In addition to these primary sources, secondary sources included newspaper accounts, letters, biographies written by children or spouses, military records and memorabilia, and photographs. For example, one participant shared the letters she wrote home while serving in the European theater during World War II. One, written from somewhere in France on January 27, 1945, reads: “Dearest Mother and Family: Writing by the light of a dim lantern is rather difficult. At least now we have a fire going in the little stove in our tent. We are settled in these humble living conditions [fourteen in one tent], but are thankful that it will not always be this way.”

Some of the participants became very emotional as they recalled challenging experiences.

As interviewers, we offered support, waited in silence, and then asked them if they wished to continue. Some had never discussed their military service with their families and found it helpful to talk with an interested investigator. Articulating their memories seemed to validate their perceptions and help them draw meaning from their experiences. Many expressed the sense that having this opportunity to share their perspectives was actually therapeutic, although this was not the intent of the project.

Historical Background

It is important to understand from whence the profession of nursing came in order to understand the foundation of professional nursing. “Professional nursing began on the battlefield,” says Paul Kerry, professor in the History Department of Brigham Young University. We see evidence for that statement in the lives of Florence Nightingale, Mary Jane Bickerdyke, and Clara Barton.

Florence Nightingale went to Scutari, Crimea, as a representative of the British government in an effort to improve the situation of sick or wounded British soldiers during the Crimean War. She wrote: “We have now four miles of beds—and not eighteen inches apart. . . . These poor fellows have not had a clean shirt nor been washed for two months before they came here, and the state in which they arrive from transport is literally crawling. . . . When one poor fellow who is to be amputated tomorrow, sees his comrade today die under the knife it makes impression—and diminishes his chances. We have Erysipelas Fever and Gangrene” (Florence Nightingale in Dossey 2000, 125–26).

The Barrack Hospital sat over a network of cesspools, but sewer lines were blocked and privies overflowed into the hallways. Windows were closed against the cold, wind, and rain, trapping the stench from the sewers together with smoke from the stoves. The water supply was visibly contaminated with organic matter. Not surprisingly, cholera, typhoid, and typhus added to the toll of illness and death. (Dossey 2000, 126)

In comparing Nightingale to Vietnam War nurses, Barker suggested that Nightingale might have suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. She commented that Nightingale suffered somatic symptoms for much of the rest of her life. She never nursed again and was rarely seen in public. However, she was a prolific writer and advocate for the causes of the British soldier, sanitation, and educated nurses (1989, 630).

Nightingale’s nursing activities to improve the quality of life for British military men threatened her physical and emotional health, social standing, and family approval. However, she brought cleanliness, reduced infection, improved ventilation, privacy, and improved nutrition to those who were ill, and her practice became the basis of the standard of patient care that has continued to the present.

Mary Jane Bickerdyke, another early nurse, was a widow with two sons who supported her family by doing home nursing during the American Civil War. Some of the men at the Union camp in Cairo, Illinois, were ill and dying even before the first battle of the Civil War was fought. Gangwer wrote:

Believing it was the Lord’s work that she was called to do, Mrs. Bickerdyke placed her sons in the care of friends and left her home to take the supplies to Cairo. When she arrived, she was appalled at what she saw. There were three hospital tents crowded with cots; the ground inside the tents was covered with wet, dirty straw. Flies swarmed around the water buckets. The “noxious effluvia” was overpowering.

Mrs. Bickerdyke rolled up her calico sleeves, asked for some able-bodied men to help her, and went to work. Under her orders, they shovelled out the tents, made barrels into bath tubs, and drew fresh water for the drinking buckets. The patients were scrubbed with her yellow soap while she made up the cots with clean linen she had brought. Dirty clothes were laundered or burned, and clean clothes supplied. She enlisted the help of Cairo citizens to set up laundries in the camp as well as kitchens. Special food was prepared for the sick instead of the usual ration of bacon and beans. One of her soldier helpers, a young man named Andy Somerville, told her that she reminded him of his mother and she soon became known as “Mother” Bickerdyke. She has also been called the “angel of Cairo” and a “cyclone in calico.” (Gangwer 1998, 11–12)

At one time she ignored the orders of one of the contract surgeons, who then complained to General William T. Sherman. Sherman replied, “Oh! Mother Bickerdyke outranks me. She takes her orders from God” (Gangwer 1988, 12).

Clara Barton also provided nursing care during the Civil War, including in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in May 1864, after the Battle of the Wilderness. During that battle, 21,700 soldiers were either killed or wounded. Barton’s description of the situation after the battle speaks to the terrible conditions suffered by military men during the war:

I saw, crowded into one old sunken hotel, lying helpless upon its bare, wet, bloody floors, five hundred fainting men hold up their cold, bloodless, dingy hands, as I passed, and beg me in Heaven’s name for a cracker to keep them from starving (and I had none); or to give them a cup that they might have something to drink water from (and I had no cup and could get none). . . . I saw two hundred six-mule army wagons in a line, ranged down the street to headquarters, and reaching so far out on the Wilderness road that I never found the end of it; every wagon crowded with wounded men, stopped, standing in the rain and mud, wrenched back and forth by the restless, hungry animals all night from four o’clock in the afternoon till eight next morning and how much longer I know not. The dark spot in the mud under many a wagon, told only too plainly where some fellow’s life had dripped out in those dreadful hours. (Barton 1922, 277–78)

During the Civil War, Clara Barton independently managed a large-scale war relief operation in which she arranged for huge quantities of supplies to be furnished to the army and the hospitals. She impartially cared for the casualties of both the Federal and Confederate armies, for both blacks and whites. She was frequently in physical danger, being shot at as she tended to those on the battlefield. The ideals of caring for anyone in need, regardless of their physical, social, or financial situation, are the ideals embodied in the organization that Barton helped to organize: the American Red Cross (Donahue 1985, 294).

Those who served as nurses during the American Civil War elevated the standard of patient care in providing comfort and life-saving measures. They sacrificed personal comfort, possessions, and welfare to care for those who served on both sides of the conflict. They added to Florence Nightingale’s foundation for modern nursing. Their actions have been described as follows:

Despite the early skepticism of the surgeons and the general public about the propriety and ability of women to serve as nurses, these women showed the world they had the stamina, commitment, organizational ability, and talent to become a vital force in the nation. They not only opened up nursing as a career for women in America but laid the groundwork for developing the modern hospital. But perhaps the truest measure of their accomplishment is the effect they had on their patients. If some surgeons still retained their prewar prejudices about female nurses, these were offset by accolades from the returning veterans. (Culpepper and Adams 1988, 984)

Challenges came in many forms, including a lack of acceptance, impossible sanitary conditions, supply shortages, and a general lack of training. Each difficulty produced changes and advances in the nursing field that would affect all future generations of nurses. The methods perfected and the challenges met by these pioneering nurses would set a standard of advancement and excellence in the field beyond anyone’s imagining. (Purcell 2000, 18)

The Civil War revolutionized nursing care in the United States. For the first time in American history, well-educated, respectable, middle-class women were encouraged to use their knowledge of nursing to care for ill, injured, or infirm military personnel outside their own circle of family and friends. The war generated an increase in the demand for systematic educational programs designed to inculcate in women a knowledge of the principles of nursing care. Women breeched the social barriers to practicing nursing in hospitals, never again to be barred from the wards by social conventions. They won the grudging respect of surgeons and were often idolized by their patients. Many of the women became regional heroines, and a few became national legends. (Rogge 1987, 26)

The nineteenth century also provided examples within the Latter-day Saint community of the caring and sacrifice typical of pre-professional nursing. These examples are accompanied by faith in the power and will of our Heavenly Father to bless His children. One example is that of Amanda Smith at Haun’s Mill, Caldwell County, Missouri, on October 30, 1838, and is best told in her own words:

I suddenly saw the mob coming. . . . I seized my two little girls and escaped across the millpond on a slab-walk. . . . Yet though we were women, with tender children, in flight for our lives, the demons poured volley after volley to kill us. . . . When the firing had ceased I went back to the scene of the massacre, for there were husband and three sons, of whose fate I as yet knew nothing. . . . Passing on I came to a scene more terrible still to the mother and wife. Emerging from the blacksmith shop was Willard, [Amanda’s son] bearing on his shoulders his little brother Alma.

“Oh, my Alma is dead!” I cried, in anguish.

“No, mother; I think Alma is not dead. But Father and brother Sardius are killed!”

. . . The entire hip joint of my wounded boy [Alma] had been shot away. Flesh, hip bone, joint and all had been ploughed out from the muzzle of the gun which the ruffian placed to the child’s hip through the logs of the shop and deliberately fired. The bones that remained were three or four inches apart.

We laid little Alma on a bed in our tent and I examined the wound. It was ghastly sight. I knew not what to do. It was night now. . . . Yet was I there, all that long dreadful night, with my dead and my wounded, and none but God as our physician and help.

“Oh, my Heavenly Father,” I cried. “What shall I do? Thou seest my poor wounded boy and knowest my inexperience. Oh Heavenly Father, direct me what to do!”

And then I was directed as by a voice speaking to me. The ashes of our fire was still smoldering. We had been burning the bark of the shag-bark hickory. I was directed to take those ashes and make a lye and put a cloth saturated with it right into the wound. It hurt, but little Alma was too near dead to heed it much. Again and again I saturated the cloth and put it into the hole from which the hip joint had been ploughed, and each time mashed flesh and splinters of bone came away with the cloth; and the wound became as white as chicken’s flesh.

Having done as directed I again prayed to the Lord and was again instructed as distinctly as though a physician had been standing by speaking to me. Nearby was a slippery-elm tree. From this I was told to make a slippery-elm poultice and fill the wound with it. . . . I made the poultice, and the wound . . . was properly dressed. . . .

I removed the wounded boy to the house of Brother David Evans, two miles away, the next day, and dressed his hip; the Lord directing me as before. I was reminded that in my husband’s trunk there was a bottle of balsam. This I poured into the wound, greatly soothing Alma’s pain.

“Alma, my child,” I said, “you believe that the Lord made your hip?”

“Yes, Mother.”

“Well, the Lord can make something there in the place of your hip. Don’t you believe that he can, Alma?”

“Do you think that the Lord can, Mother?” inquired the child, in his simplicity.

“Yes, my son,” I replied, “he has shown it all to me in a vision.”

Then I laid him comfortably on his face and said, “Now you lay like that, and don’t move, and the Lord will make you another hip.”

So Alma laid on his face for five weeks, until he was entirely recovered—a flexible gristle having grown in place of the missing joint and socket, which remains to this day a marvel to physicians.

On the day that he walked again I was out of the house fetching a bucket of water, when I heard screams from the children. Running back, in affright, I entered, and there was Alma on the floor, dancing around, and the children screaming in astonishment and joy. (Hodson 1996, 78–84)

Another example of caring in early Latter-day Saint history is the brief account of care provided to Joseph Smith after a mob had tarred and feathered him at the John Johnson farm on March 24, 1832. The mobbers dragged him out of the house, tore off his clothes, scratched his body with bare fingernails, and covered him with hot tar and feathers. Unsuccessful attempts were made to pour tar into his mouth and to poison him. Joseph reported, “My friends spent the night in scraping and removing the tar, and washing and cleansing my body; so that by morning I was ready to be clothed again” (Smith 1980, 264). Though Joseph reported this care in the few words characteristic of many plainspoken frontiersmen, the act itself was probably not small. It took all night and required that cooled tar imbedded with feathers be stripped from skin that had been burned and scratched.

Sorensen, in her work on Mormon nursing, notes, “The unquestioned origin of professional nursing among the Latter-day Saints is found in the sisterly acts of pioneer midwives. In Nauvoo, midwives Patty Sessions, Vienna Jacques, and Ann Carling had been set apart by the Prophet Joseph Smith to care for the women of the Church. The work of the midwives continued in the Salt Lake Valley, as they combined faith with practical skills, offering spiritual gifts with physical comfort” (1998, 53). Sorensen continues with a concise summary of pre-professional nursing among Mormon women:

Social and philosophical upheaval also profoundly affected the daily lives of turn-of-the-century Mormon women. Women had walked beside male priesthood leaders through the years of forced emigration, from Ohio to Missouri, Missouri to Illinois, and from Illinois across the country to the Salt Lake Valley. All the while, they re-established homes, cared for the sick, delivered infants, reared children, anointed and buried the dead, and provided for entire households while men were away as scouts, soldiers, missionaries, or polygamist fugitives. Such adversity and responsibility, as well as the pervading characteristic of daily life of essentially separate cultures for men and women, promoted a fierce independence and leadership among Mormon women. Devoted to their faith, their families, and to the success of the Church, women exhibited a social and political progressiveness unique in their history and contrary to their public image. (1998, 55)

About This Study

Firsthand accounts appear alphabetically by the nurses’ last names. Several common themes emerged as the nurses discussed both their professional and personal experiences. The main theme was “We did what we had to do.” Nurses demonstrated strength and courage associated with their spiritual lifestyle. This is perhaps best exemplified in the words of an army nurse serving during World War II spoken with pride: “We had chosen a profession that required our best in brain and brawn.” Even fledgling nurses had a sense of mission and purpose, as one stated: “The work and studies were demanding. Our work gave us a warm feeling of helping the war effort. To this day I do not know how we had the strength to do what we did. We gave such support to each other. Being a nurse called for such sacrifice, that only the finest type of woman could fulfill.

Professional themes included short staffing, long hours, and insufficient supplies calling for creativity and ingenuity in clinical practice, even for the cadet nurses. One cadet nurse whose brother died landing in Okinawa, wrote in June 1944: “Very few graduate nurses worked in the hospital at this time. Our head nurses, supervisors, and instructors were graduates. The main work force were student nurses in various stages of training. We had excellent and difficult experiences. We worked hard, we became efficient, and grew in responsibility.”

Another cadet nurse wrote about the relative lack of effective medications and equipment even stateside during World War II: “They did not have antibiotics when I was a student. Sulfa came in about the time I graduated. Many people died of pneumonia, which was one of the major killers. There were no respirators or anything of that sort. There was none of the wonderful equipment we take for granted today. The IVs and blood transfusions were nothing like they are today. We used very primitive homemade gastric-suctioning machines. For incubators for premature babies, we had a box with a light bulb in it.”

Nurses treated victims of shock and trauma, as many of them practiced before the establishment of critical care units in the 1960s. They cared for patients with post traumatic stress syndrome, which was not identified as an official diagnosis until after the Vietnam War. They cared for patients with unusual diseases not typically seen in clinical practice, including jungle rot and other skin conditions typical in the Pacific Theater in World War II. Sometimes they were in situations where they were required to provide care that was beyond their scope of practice under very difficult circumstances. Often they had profound emotional experiences. Speaking about receiving 1,062 former prisoners of war at the end of the Pacific conflict in World War II, a navy nurse said: “Soon our patients began arriving, many emaciated and weak, some limping or using crutches. Our few corpsmen hurried up the road with stretchers and carried back the weakest ones. In the meantime, we nurses were assigned patients as they arrived, making sure that they each had a thorough sponge bath and clean pajamas. Then they were promptly transported to the ship (USS Consolation) and admitted to the hospital. Many of the former prisoners were American, but some were British, Australian, or from countries where I couldn’t understand their language. But sign language was adequate; smiles and happy gestures let us know that they were just as thankful to be rescued as the ones who tried to express their feelings in words or who quietly shed a few tears.”

An army nurse in the European Theater during World War II wrote about her typical working day: “Wounded soldiers were admitted by ambulance. My duties were to clean wounds, change dressings, send patients to shower, and then check them for further wounds. That meant seventy-two hours of straight duty that night and the next couple of days until we were exhausted. We worked twelve- hour shifts steady from that time on, until the end of the war [fourteen months later].”

Personal themes included fear of the unknown, a sense of uncertainty, loneliness, ambivalence about military conflict, a sense of appreciation and love for home and country, and concerns for family at home. One nurse wrote: “There were many nights in the Arabian Peninsula when loneliness and missing your family set in, and to me that is the worst feeling that anyone could experience. As Mother Teresa has said, ‘Loneliness and to be unwanted is the greatest poverty.’ I couldn’t agree more.”

The German nurse whose comment follows was only seventeen when she was pressed into service as a Red Cross nurse caring for the wounded and dying on the Russian front. Frightened and alone, she expressed the deep uncertainty she felt: “I never would have imagined that while I was on the Russian front, that my life would have taken me where it has. I thought I was definitely going to die. It was to a point that I had given up. There was really nothing whatsoever left for me.

Some study participants made meaning of their war time experiences, and described the lessons learned which profoundly affected their lives. These included living fully in the present, reevaluating priorities, cherishing freedom, valuing home and family, and having faith and trust in God. These were the values they held fast to and which sustained them in difficult times. One perioperative nurse in Operation Desert Storm, who left a wife and four young children at home including a newborn, identified the importance of living fully in the present: “Being given four days to get our lives in order was not a lot of time. The lessons learned were that one never knows what tomorrow will bring. Life is fragile, and we should live today as though it might be our last.”

Another spoke of reevaluating priorities: “I promised myself that if I made it out of this conflict, if I ever had to choose between time and money I would always chose time to be with my family and those I love.”

For the most part, study participants were very patriotic and spoke of cherishing freedom, even in those instances where they had conflicting feelings about going to war: “We should cherish freedom, and hold it so close and dear to our hearts that we would be willing to give our lives to protect the freedoms our country is based on.” Another wrote, “Ever since the day I returned home, I cannot see a flag or hear the “Star-Spangled Banner” without privately coming to attention and paying respect for the symbol that flag represents.”

Valuing home and family was a pervasive theme found in the interviews and in the letters written home: “I left my family not knowing if I was going to return. My only prayer the whole time that I was gone, was not that I would be protected, but that my [family] would be well cared for in my absence. . . . My wife said that there was a shield, a protection over our home at all times. That meant a lot to me.”

These nurses espoused a spiritual lifestyle, and this was a common thread throughout the interviews. They found strength in their relationship with a higher power and made meaning of their experiences because of their religious beliefs: “We may find times in our lives when we are totally helpless. No matter how much control we think we have over our lives, we must always remember that we have to have faith and trust in God. We are dependent on Him.”

A navy nurse who served in World War II in the Pacific Theater reflected on her experiences: “You are so aware of the Supreme Power that controls all. I know that God has been good to us for preserving us. There is joy in living—being aware that you are very much alive.”

On November 11, 2004, Veterans Day, a note dedicated to nurses was left at the Vietnam Wall. It read, “I don’t remember your name, but thanks for saving my life.” This indication of how much the quiet, unsung, heroic services of a nurse meant to this veteran is inspiring. These men and women whose stories are chronicled in this text have made a difference in the lives of countless military personnel—and though they may not remember their names, they remember the quiet presence and dedicated and competent care they received from a nurse.