Cadet Nurse Corps

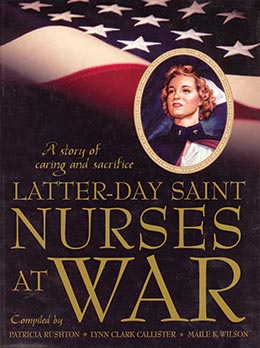

Patricia Rushton, Lynn Clark Callister, Maile K. Wilson, comps., Latter-day Saint Nurses at War: A Story of Caring and Sacrifice (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) 115–154.

Historical Background

The United States Cadet Nurse Corps was the largest and youngest group of uniformed women to serve their country during the war and postwar era of World War II. Though the original goals of the cadet program included inducing inactive nurses to return to practice and training voluntary nurses aides, the largest focus of the program was the recruitment of new students into nursing schools and the improvement of nursing education. At the beginning of World War II in 1941, a Public Health Service inventory showed there were 289,286 registered nurses in the United States. Of those, only 173,055 were active. The predicted national need for nurses at the time was 97,000. Existing nursing education institutions, about 1,300, could not stretch enough to accommodate that number. A secondary goal was set for 65,000, and 47,000 were recruited in 1942. The corps recruited nurses from July 1, 1943, to October 15, 1945. During that period of time 179,000 women, beginning at age seventeen, joined the corps. Of that number, 124,000 women graduated as nurses from 1,125 participating schools of nursing before 1948, when the corps was discontinued. Those who joined the corps received tuition, books, a stipend, and a uniform. In return, they contracted to serve as nurses in either military or civilian hospitals or in Indian Health Service or Public Health Services facilities for the duration of the war.

During the war years there was a shortage of nurses for several reasons. The direct need for nurses to care for military personnel was the most visible reason. Another reason was the growing defense industry, which contributed to a more prosperous economy. The civilian medical community was also disrupted by the fact that physicians were also called to support the military, leaving a larger portion of medical care to the nurses left in the civilian sector. The American Red Cross and the United States Public Health Service initially assisted by assigning thousands of volunteers to help with hospital care, but these organizations could not keep up with the demand.

Though the Cadet Nurse Corps only existed for about five years, its contribution has been long lasting. Eighty percent of the nursing care provided in civilian hospitals during World War II was provided by Cadet Nurse Corps students (Robinson, 2002, xi). This allowed hospitals to stay open to serve civilian populations that may have had to close otherwise because of insufficient nursing staff.

Ruth L. Johnson, a consultant with the Cadet Nurse Corps, described the improvement to nursing education produced by the institution of the corps. She noted that every school that wished to participate was reviewed. They needed to meet certain requirements for faculty and for curriculum content. Those schools that did not meet this criteria were closed. This elevated the level of nursing education. Schools were also required to have budgets independent of the facility with which they were associated. This began the process of making schools of nursing independent of hospitals and medical staffs (Robinson, 2002, chapter 2).

Finally, the nurses who were educated by the corps have become leaders in the profession, educators for current nursing programs, and care providers for millions of Americans.

Rayola Hodgkinson Andersen

War was raging. Nurses were desperately needed. The government started the United States Cadet Nurse Corps. If you joined, your tuition and housing were paid. That was good, since I came off the farm in Vernal, Utah, and had no way of paying for my education.

When we started nursing school in 1945, we were issued summer uniforms and winter uniforms. We only wore them when we had to appear for inspection and when we went to the movies. If we wore them to the movies, we got to go in for free. We started nursing school by living at Carlson Hall, which was University of Utah housing, for six months. We took all of the preliminary classes in anatomy and physiology and the nursing arts. We transferred to LDS Hospital after about six months and lived in housing on State Street and First Avenue. It was a two-story building. We had a housemother. We had to be home every night at 9:00 p.m. and were locked in. It seems like it was 10:00 on Fridays and 11:00 on Saturday night. After our first year we moved to the LDS Hospital Nurses’ Home on Ninth Avenue. However, we were still locked in after 9:00 p.m. We had classes in the afternoon. It was so hot, and of course, there was no air conditioning. After a couple of months we started working on the medical-surgical floors in the hospital.

While we lived there we had classes at the LDS Hospital. We had to get up and catch the Ninth Avenue bus by about 5:30 in the morning so we could have breakfast and get to class. We had class from 8:00 am until noon. We learned about all the diseases. It was after these fundamental nursing classes that we began to be checked off on our nursing skills at the hospital. I remember that the nurses—really our nursing instructors—were not particularly kind or understanding. We had bedside stands. The bedpans were supposed to be on the bottom, and the bath basins were on top of the bedpans and other paraphernalia in the drawers. When one of my instructors was checking one of the patients that I had, some other nurse had come along and given the patient their bedpan, but she didn’t put it under the basin. The instructor really scolded me about that. You didn’t ever say anything. You just stood there and let them yell at you. The instructors would check to see if you made the bed right with square corners. She would run her fingers across the windowsills and across the top of the clothing closet to make sure you had done everything exactly right.

It was such a scary thing to be with the instructors. They scolded us often. The floors in the work area in the utility rooms had little octagon tiles on the floor. As I was getting scolded I used to count them to see how many I could count before they stopped getting after me. They’d say, “Miss Hodgkinson, what have you done wrong now?” I often thought that if I had known what I had done wrong, I wouldn’t have done it. So I wasn’t even sure what it was they were getting after me for part of the time. During this time of instruction and class work we had to go to choir. Archibald Bennett was the choir director. He happened to end up being a senator in the United States Senate back in Washington DC for many, many years. However, he always loved the choir we had at the nursing school. Even if you couldn’t sing, you still had to get up at 6:00 a.m. every morning and go to choir.

As soon as we finished basic training, we worked at the hospital from 7:00 until 11:00. Then we would eat and go to class. We would then work from 4:00 until 10:00. That was our day’s activity and we really had to work hard. After the first year, we started working with other nurses until we could work the night shift ourselves. I remember the first night I worked, I was on a medical floor with Evelyn Plewe Jorgensen. She was a year ahead of me. I was so scared that someone would die because we had a lot of people who did die. I would take a flashlight and creep into the room and see if the patients were alive. I couldn’t even tell if some of them were breathing. I asked Evelyn what I should do. She is a character. She said, “I guess you better wake them up.” It was really scary because we had a lot of deaths.

At that time, a hospital was not a place to get better. It was a place to die. Anyone who broke their hip died, anyone who got pneumonia died, anyone who got cancer died, anyone with a ruptured appendix died. Premature babies rarely, if ever, lived, and little kids with whooping cough or croup often ended up dying. One of the most feared diseases in little kids or adults was polio. I remember that Mrs. Lake, who was paralyzed, was in the hospital for over a year. In 1952, after I graduated from nursing school and had been on an LDS mission to Norway, the old county hospital had iron lungs everywhere for people with bulbar polio. It was the most dreaded disease of its time. The Salk polio vaccine came out in 1954, and everybody took the shots to begin with. Later the vaccine was given in drops. It was interesting that since the development of the Salk vaccine, I have only seen one case of polio. It was a little eight-year-old child, and it was very mild. That disease has been eradicated in our country.

We had a lot of little kids with rheumatic fever in my early days of nursing. It was so prevalent: little kids with swollen joints all wrapped up in cotton and having a lot of pain.

One of the things everyone worried so much about at that time was a patient getting a red streak up the arm or leg from an infection. If someone got one of those, everybody got busy and hot-packed the infected area, and the patient got put on bed rest.

I remember we had a lot of drunken people who came in hallucinating and having DTs (delirium tremens). We would give them a huge 5 cc injection of paraldehyde in their hip. The way it dissipated was through their breath, so their breath smelled like paraldehyde for a couple of days.

After a year and a half we would start working as the charge nurse on afternoons and nights by ourselves. We worked forty-eight-hour weeks and stayed late after our shift most of the time. We always did everything we could not to get the supervisor involved. Mrs. Reed was very nice, but Miss Clara Wall wasn’t all that nice. I remember so well that if anybody couldn’t sleep, we had to rub their back and give them a glass of hot milk, and usually it helped.

During those years of our hospital work, we didn’t have many drugs. We had morphine and Dilaudid for pain, Nembutal and Seconal for sleep, and phenobarbital for calming people down. Of course, there was always codeine and we had paregoric, which we used a lot. I think penicillin and sulfa were just discovered and began to be used during the war. I remember my very first penicillin shot. We had our own little 3 cc luerlock syringes and the barrel and the plunger had numbers on them and they had to match. We had our own needles and we had a little pumice stone that we sharpened our needles on. We had to boil the syringes and the needles three minutes between shots. The penicillin was given every three hours around the clock. I remember the gentleman that I gave my very first penicillin shot to. It was an IM injection. He was paralyzed. His name was Tommy Shields. His spine had been crushed while working on the railroad, and instead of taking a cash settlement, he decided to live on the railroad ward for the rest of his life. He was really a prankster, which I didn’t know at the time. I boiled my syringe and pulled up the penicillin, and I went shaking, scared to death to give this shot. I didn’t notice that he was watching me and when I touched him with the needle he started screaming loudly. I just stuck the needle in. I forgot all about pulling back the plunger to see if there was any blood in it. I just pushed in the medicine and fled into the hall, scared and shaking. Then I heard him start laughing. It dawned on me that he was paralyzed and couldn’t even feel the shot.

We made rounds with the doctors too. One of the surgeons, a Dr. Richards, would come on. We would go with him to see the patients. The protocol was that he went first, the resident went next, then the intern, then the medical students, and then the nurse would tag along last. The doctor would change the dressing and then he would turn to me, the nurse, and say, “I want a piece of tape eight inches long.” I could exactly eight inches, so I would tear him a piece of tape. I would give it to the intern, he would give it to the resident, and he would give it to the surgeon. Dr. Richards would wad it up and throw it in the wastebasket. Then, he would say, “I want an eight-inch piece of tape.” The resident would cut him a piece of tape, and he would put it on the dressing. It didn’t matter how long the piece was. The doctor would tape it on. It was really an interesting relationship with the doctors. I remember in surgery when one of the clamps wouldn’t clamp, the doctor would throw it across the room and hit the wall. I remember one of my classmates who was a very tender, sweet girl. She got a clamp that didn’t work, so she just threw it across the room. She didn’t realize that only the doctors got to do that. It was a very stressful time, and my roommate packed up to go home a couple of times, but I would talk her out of it. I was going to leave once. It was just too much stress and too hard a work. It was awful. But my roommate talked me out of leaving too.

We had a lot of camaraderie and a lot of fun. It was during the war, and things were rationed. One night we made some fudge up on the seventh floor. We didn’t even think you could smell it throughout the whole hospital. It was the middle of the night. We had it all finished and the supervisor, Miss Wall, came up and scolded us, but not too bad. We gave her a piece and she said, “Well, don’t do it again.” Those were wonderful times. We bonded with each other as nurses and to this day are still very good friends. Some of the doctors were really nice. One of them was Dr. White. We had a basketball team, and after every game he would take us over to Snelgrove’s Ice Cream Parlor, and we could buy anything we wanted. I always had a strawberry parfait. It had pecans in it. It was such a luxury for me in those days.

One can never think about the nurses training in those days without thinking of all of the thermometers we had. We had to shake them all down by hand. We got smart and would put them in a little hand towel and shake them. Once in a while, if we didn’t hold them tight, some of them would slip out and break. We always had to pay for anything we broke like that. All of the catheters had to be boiled and used again. Sometimes they would boil dry and everybody would know when we had made that mistake by the smell of burnt rubber all over the hospital. The doctors always had to do the blood transfusions. In the very early days of my training, the interns had to stay with the patients, if they had an IV, the whole time it was running. I remember we had a nurse by the name of Miss Ingersoll who gave the first blood transfusion by a nurse. We didn’t have filters, but they did have some kind of a little chamber that they filled with sterile cotton and the blood dropped through the cotton into the patient.

At the Cottonwood Maternity Hospital, sometimes they would have a really ill baby that they didn’t expect to live because it had low blood. Since I was so young and energetic and had a lot of meanness I guess, they would sometimes ask if they could take 10 cc of blood to give the baby. They never typed or crossmatched blood in those days and to my knowledge never even typed the baby. They would give the baby this 10 cc of blood. I never minded or had any objection to that. About twenty years later I was out in my garden and this beautiful eighteen-year-old and her mother came to the back of my garden and said, “Are you Rayola Andersen?” I said, “Yes, I am.” The mother started crying and said, “I want you to meet my daughter. You are the one who saved her life.” I said “My gosh, what was that all about?” She said “When she was a baby they never expected her to live so they gave her some blood that you had given. I have kept track of you in the newspaper because you were on a basketball team, and the one time you saved that man’s life, and that was in the newspaper. I have always been grateful and I have always wanted to come and tell you thank you.” I thought that was a beautiful thing, even though I really hadn’t done anything to get credit. I think nursing is a wonderful profession.

One of the things that had to do with the war quite directly was that there were soldiers who lived out in the barracks at Kearns, Utah. Of course most of us nursing students were young and nave and came from country towns around Utah, and those fellows came to date us since we were in the nurse corps. We thought they were quite strange and they thought we were quite strange. But we had a lot of fun dating them, and it helped them to not be so lonely being so far from home.

Perhaps the most memorable nursing situations that I had were during my rotation onto the pediatric ward. I still remember the names of many of those little patients. There was an eighteen-month-old boy with blue eyes and blond curly hair who was admitted with a severe case of croup. We had no particular medicine for croup. We used a humidifier when we should have been using something cold. He went into severe laryngeal spasm. I held him in my arms while the clerk tried to hunt the intern by phone. We had no other way to communicate except by phone. The baby started to turn blue. I tried to put my fingers between his teeth to try and let air in because I didn’t know anything else that I could do. It took about ten to fifteen minutes to find the intern, but the little fellow died before the doctor got there, and that was really a traumatic thing.

Another experience that demonstrates the nursing care of that time was a six-year-old named Johnny. At his birthday party they were having a weenie roast. He got a pair of cowboy chaps for his birthday, and they were highly flammable. One of the little boy guests picked up a burning stick and threw it at him and hit him in the leg, catching the chaps on fire. Before his mother could smother the flames, he had second-degree burns and in some spots third-degree burns. They brought him into the hospital to die. We smeared Silvadeen salve all over his burns and wrapped him in gauze bandages from his waist to his feet and gave him morphine for the pain and just expected and waited for him to die. We didn’t have any screens on the windows, and flies just flew in and out of the hospital rooms. Johnny didn’t die. After about a week the doctor decided we had to change the dressings. We put him in a tub of warm water to soak them off. After about ten minutes the water was totally covered with maggots. In spite of how gross and nauseating it was, the maggots had actually eaten all of the dead tissue, and little Johnny started healing. He was able to leave the hospital in about three months walking, even though it was stiff-legged. Actually, after that they began to implant maggots into wounds because they didn’t do any harm to the body; they only ate up the necrotic tissue. An interesting side light to that story happened thirty-two years later. I have a couple of rental houses. A rental couple had bought a house of their own and had moved, so I was running a rental ad. A gentleman called and came to see the house. After the tour and discussion of the rental agreement he smiled broadly and said, “You don’t know who I am, do you?” I apologized and explained that I was a nurse and met many people and because of that I didn’t really know who he was. He grinned and said, “Yes, I know you are a nurse because many years ago, I was badly burned from the waist down and you were one of my nurses.” I really couldn’t believe it, but I said, “You’re Johnny.” We hugged and discussed what his life had been like.

While I was a student, one of the students came to work with her engagement ring on. Her supervisor saw it and told her to take it off because we were never allowed to wear any kind of jewelry. The student said, “No, it is my engagement ring and I don’t want to take it off.” She was told she would either take it off or she wouldn’t be a nurse. She said, “Well, I am not going to take it off.” She actually had to leave nursing over that engagement ring. After that we got smarter. One of my good friends got married, but nobody ever knew it. We were always trading shifts or doing anything we could so she could go out with this boyfriend we thought she had. In reality she had gotten married. She kept it hidden until we finished our program.

One type of case that was very difficult for patients and families and for us was a patient that had cancer with a fistula to the outside. The odor was terrible and almost unbearable. We would put some pine stuff in water and use a fan to move the air around to try to make it smell better. But I don’t think it helped much because it was just dead body tissue from growths that didn’t have enough blood to supply the tissue, so it died. I think of people saying how terrible cancer is nowadays, but we never have smells like that anymore. Fifty percent of all the people who get diagnosed with cancer are walking around on the streets or are in remission under treatment. We have all kinds of treatments and palliative care and are making great strides in curing many kinds of cancers.

We had many patients who had large goiters, some bigger than large grapefruits, and the only treatment was surgery. All of the patients had waited until it was pressing on the trachea and they could hardly breath. The typical visual sign was exopthalmic (bulging) eyes. I remember that occasionally the patient would have what was called “thyroid storm.” These patients would become delirious and had high fevers, abnormal heart rhythms, and extreme sweating. They became very shocky. We had to cool them rapidly and give large doses of adrenal corticoid hormones. I was fortunate; I never saw a patient die from this.

Another interesting thing we saw then that we never see anymore was patients with renal failure, called uremia. We didn’t have dialysis, so they had severe ascites. The treatment was to do a paracentesis when their breathing was compromised. These patients would develop sandlike granules around their nose, armpits, and wherever they perspired a lot. It was their bodies’ way of getting rid of the uric acid that their kidneys could not.

Patients with liver disease always ended up dying. My most memorable patient was an American lady about thirty years old who had been working in Japan and was taken as a prisoner of war at the beginning of World War II. She said she pulled a little plough during the day in the rice paddies and was strapped down for the Japanese soldiers’ pleasure at night. She had liver failure from the lack of protein in her diet; and suffered from severe ascites. We did a paracentesis every second or third day, which was the only treatment, when it caused her problems with her breathing. However, the procedure only encouraged the accumulation of more fluid in her abdomen and the continuation of her ascites.

Another thing we used during wartime—and I have never seen it used since—was sawdust in bed frames. People who had terrible decubitus ulcers that were draining would lie on the bed, and all the drainage would go into the sawdust. It had some real beneficial effects except that it was so uncomfortable for the patients. I think that is why they discontinued its use and found better ways of taking care of the problem. Another thing that we used to do was use Wangenstein drainage systems. You would put water up in the top, and the pressure of it would go down and take out the drainage from the stomach or whatever it was that was draining. It was a very happy day to see all of those disappear. During the war there were two cure-alls. If you ever got a cold, you got a mustard plaster. All it ever did was burn your skin. I guess it felt so good to get it off that you didn’t complain any more. Another thing was that everyone was obsessed with bowels in those days. If anyone ever complained about anything to do with their bowels, the first thing we did was give them an enema. To prevent that, almost every night all the patients would get a black and white toddy made of cascara and milk of magnesia. The patients hated that, but they never ever got constipated.

Many injured servicemen ended up at Bushnell Hospital in Brigham City, Utah. These patients had lost arms or legs or were badly burned or had other major injuries. Some of us students would hitchhike to Brigham City. We didn’t have cars or money for bus or train rides, and hitchhiking was a safe way to travel at that time. We would go to Bushnell and date these soldiers. It was interesting to see what difficulties they had in trying to cope with their injuries. They liked to have us come because we kidded and joked around, and they felt so comfortable with us. One of the soldiers was a big guy from Texas. He had lost both legs. He asked why I would be interested in coming up there to see him. I told him, “Well I feel pretty safe with you. I know you can’t catch me.”

I was in Norway in 1950, just after the war. When I saw the tragedies of war, I thought then that it is the most awful evil that can ever come into the world. When I saw the kind of care that those people got compared to the kind of care that we had, even in those days, it was a blessing. In the State of Utah—I admit all of my biases right now—we have the most up-to-date healthcare of anyplace in the United States.

I have always loved nursing. I am still involved in nursing and am able to contribute to the wonderful profession and provide care to those who are so much less fortunate than I am.

Note: Evelyn Plewe Jorgensen observed in 2003 that Rayola Andersen was the only member of their nursing class still to be actively working in the profession.

Beth Smith Edvalson

“Why don’t you become a nurse?” my older brother asked. My response was “Hmm.” If I make a snap decision, it is usually wrong. I decided to think about it. I was already working six hours in the evenings, two or three days a week, at the local hospital. It was in a volunteer capacity, but I liked helping people and associating with nurses.

The war had started. My brother had enlisted and was flying a bomber. Most people’s lives were anything but stable. My mother had died a few years previously, and my father and I lived in my stepmother’s house.

I don’t remember how I heard about the Cadet Nurse Corps, but it sounded like a marvelous plan for me. Now I can see the hand of the Lord in my life. My father was a farmer and had little money. I had a brain and a strong body, so why not put those attributes to good use helping others? My father was against nursing as a profession because “it was not a respectable occupation for a woman.” Other than offering his opinion, he didn’t protest my decision.

In June 1943 I entered the University of Utah with about ninety-nine other young women and spent two days taking entrance exams for nurses. I think we were part of the second group in the Cadet Nurse Corps.

Where could you find a better offer for an education? Three years equivalent to college credit, a gray dress uniform, three nursing uniforms, housing and food all furnished, plus $21 a month. It seemed like a sweet deal to me.

At this time I learned that my brother, my childhood companion, was missing in action over the Himalaya Mountain while on a bombing mission into China. I mourned deeply, but I remembered his admonitions: “You have been taught the right way to live. It is your fault if you do not learn. Always ask questions if you don’t understand something.”

After six months on campus, our group was divided and sent to our chosen hospital. Some went to Holy Cross, some to Salt Lake City General, and some to St. Marks. I went to Dr. W. H. Groves LDS Hospital. Some of my group who went to LDS Hospital were housed in the Beehive House in the city and had to ride the bus up to the hospital for classes and to work. I lived in the “cottages” across the street from the nurses’ home behind the hospital. There were eight girls in each cottage and about four cottages. They had been private homes but were converted to house student nurses. We ate our meals in the basement of the nurses’ home where the older student nurses lived.

We finally were issued our white uniforms. They were laundered in the hospital laundry and were starched so that they could almost stand alone. Still no cap, but we really liked our uniforms. The white stockings and shoes we furnished ourselves. Nylons were hard to come by. In order to get them, we had to put our name on a waiting list at the stores. When we could get them they wore like cast iron. Most of us soon discovered better shoes than the regulation Red Cross style.

We learned all the patient care procedures like the art of making a bed with a patient in or out of it. At one point I was the patient and the instructor lectured on and on. I could hear her as well with my eyes closed as with them open. I heard her say, “Well, our patient, Miss Smith, has gone to sleep!” My eyes flew open, everyone was laughing, and I was so embarrassed. Miss Shelton, a stern-faced woman with a twinkle in her eye, just looked at me.

For those first six months at the hospital, we worked when we were not in class. The day we received our caps was a proud day! The thin black ribbon would come at the end of the second year. We had been in the program a year when we received our cap, and it was time we earned our keep.

After we were worked into the system, I really liked it better. I didn’t mind doing all the grungy work because it was part of the job. We gave enemas, bathed men, catheterized women, and dug impacted stools out of the elderly. One time a very old woman needed to give us a sterile specimen, and she fought us as we tried to catheterize her. The resident doctor that had ordered the specimen walked regally in the room, put his hand on her bare thigh, and in his bass voice said, “Now look here, Mrs.———.” She let out a scream and grabbed the sheets and curled up in a ball. Needless to say we never did get a specimen, and she left the hospital the next day.

One time a three-month-old baby was admitted to the isolation ward on my floor. She didn’t look very ill, but I placed her on the bed elevated on pillows and sent for oxygen. Her temperature was 100 degrees, and she was pale. I turned my back to get something, and when I looked at her again she was dead. I wanted to shout and say “Hey, wait a minute, we haven’t done anything for you yet!” That was my first experience with death and being first on the scene. It was so final! We had not been taught first aid yet because they were afraid that we would use it on our patients. All I could do was run for help.

The hospital was big and drafty, and on winter nights the wind would howl and moan down the elevator shafts and through some of the doors that led to the sun rooms. The morgue was in the drafty basement, which also housed the diet kitchen, the laundry, and so forth. Late at night it was a super scary place to be.

If we made a mistake in our charting we had to recopy the whole page, including everyone else’s notes, and they had to initial them. We had a narcotic count on every shift. We had to sign for each pill or dose of narcotic we used and if we dropped it or had an accident with it, we had to fill out a form in triplicate and have them all notarized. All narcotics were in pill form, and one night I took one of those tiny little white pills and dropped it. I searched that white tiled floor on my hands and knees with no results. I prayed because I couldn’t think of anything else to do, then I got up off my grimy white knees and glanced into the ice chest. There on the very edge was my little white pill. I was so grateful for that help.

Seldom did anything come dose-packaged. We had to mix most things such as penicillin. One time I was going to help a resident administer some medicine to a young man in his spine. The patient was already paralyzed, but he had an infection. The doctor told me how to mix the medicine, but I read the bottle, and he had me mix it too strong. I didn’t know what to do, and there was no one to ask because I was the charge nurse and he was the doctor I might have consulted. I mixed it as he said, but I have always wondered about it. The patient died in spite of us.

We were not allowed to draw blood or start intravenous fluids. We had to call a supervisor or an intern. Most of us senior nurses could do a better job than the interns, but we had to let them try. Starting an IV is a matter of feel, and some people just never got the hang of it. Most nurses carried three pieces of equipment in their pocket: bandage scissors, a kelly clamp, and a pen. One time a resident was starting an IV, assisted by one of our perfectionist nurses—the “not a hair out of place” kind—and she was a good nurse, which made it worse. The doctor got the needle in the vein and called for the clamp. As I walked into the room I saw Nurse Perfect whip out her kelly clamp, which turned out to be her scissors, and cut the tubing. Wow, what a mess! The sticky glucose fluid was running all over the floor and Nurse Perfect was paralyzed. I whipped out my kelly, I looked at it first, and clamped off the tubing. I don’t remember whether the doctor had to start over from scratch or not.

I liked surgery; even counting all the sponges and instruments afterward was all right. We had to wash and pack the instruments and put them in the autoclave after each surgery. It was the night nurses’ duty to sterilize them all. Every so many days we would have to wash the operating room walls and floors down with an antiseptic of some kind. That was one of those things that went with the job. I didn’t like brain surgery; the instrument sounds were weird and there was always tension in the room.

My favorite floor was obstetrics. Everything was happy there, usually. I delivered babies a time or two because the doctor didn’t arrive in time. Quite often as I was shaving a woman, I would realize that I was about to give the baby its first hair cut.

When we had been in the hospital two and one half years, we were divided into groups for our final six months. One third went to the navy, one third went to the army, and one third of us stayed at the resident hospital.

We were not allowed to get married until we graduated. Some of the older girls broke that rule and lived with their husbands in an apartment on the sly. They would sneak out the window of the nurses’ home and make it back to work the next morning. I did ask for permission to get married and was greatly surprised that I was granted permission. Of course, my fiancé was going overseas right after the ceremony, so the decision was easy.

We set the date for July 5, and the ceremony was to take place at my brother’s apartment. Sugar was rationed, and I had collected all the sugar stamps I could find for my wedding cake. I had spent $90 for my wedding dress and had my picture taken in it, with the bottom swirling around my feet.

My intended came home on furlough. On July 3 he received a telegram that his furlough was canceled and that he was to report to Seattle, Washington, on the morning of July 7. We were married on the 4th of July, canceled all the invitations for the wedding, ate our fill of cake, and gave the rest away.

I was in Salt Lake City when the war was over, and the streets were full of people. We were cheering and jumping up and down and kissing everybody. (Well not everybody, but there were a lot of soldiers in the streets.) I have enjoyed and benefitted from being a graduate registered nurse. It was one of the best opportunities I could have had.

LaRee Williams Fullmer

When I attended Granite High School, mathematics was my best subject. I thought seriously of going into some field where I could use mathematics. However, at that time my teacher discouraged me because he thought that it was not for women. I had always thought about becoming a nurse, so I decided to take that as my second choice. I graduated from high school in May 1942 and began the course to become an RN two weeks later.

The first two quarters of our course, we students attended the University of Utah. The classes included chemistry, english, physiology, bacteriology, and others. After the Christmas holidays those of our class who didn’t flunk out moved into quarters at the LDS Hospital where we lived and worked for the next two and one-half years. I lived in Cottage Three with seven other girls. It was an old house with four bedrooms and only one bathroom, which had no shower—just an old-fashioned tub, basin, and toilet. We had to adjust to living without very much privacy as sometimes there would be one of us using the basin, one on the pot, and one or two of us in the tub. There wasn’t much hot water either. We weren’t allowed to cook, but we did sneak in a hot plate that we used occasionally. One of the specialties was taffy that tasted like the cold cream that we used to pull it because we didn’t have any butter or margarine.

In the basement of the main nurses’ home there was a dining room where all of us had our meals. The food was not the best. In fact, most of the time it was mediocre. The one thing that was served was good homemade bread. I learned to eat lots of sugar sandwiches; we would spread the bread with margarine (there was no butter) and sprinkle sugar on top. There was always endive for the salads instead of lettuce. It seemed that every Sunday was fried rabbit. I never ate it. I thought some good LDS person must have had a rabbit farm.

I remember that during the war we did not have some of the things that we were used to having. The margarine was white for awhile and then it came with a little color packet to make it yellow and eventually it came as it is now. Most of my dates during the war did not have cars, and if they did there was gas rationing. We usually walked to town or took the bus. There were no nylon hosiery. We wore cotton hose to work.

Our nursing instructor, Miss Sheldon, was excellent. From the beginning we learned and worked in the wards, giving routine bedside care until we were checked out on giving medications and treatments. We usually had at least six patients assigned to us for care. The students were a great help in the hospital because there were very few RNs at that time. At this time new mothers stayed in the hospital at least seven days after delivery, and most of that time was spent in bed. As a result most of these patients were constipated. So the night shift nurse on the maternity ward would start about 4:00 a.m. to get all of the enemas finished and the rectal tubes boiled before she went off shift.

Usually when we worked nights in the operating room, there was not much going on after we had taken care of the supplies. One night when I was on duty with another nurse, I drifted off to sleep in the wee hours of the morning. The night supervisor just happened along at that time and caught me. She gave me a note and told me to report to the nursing office the next morning. I ripped up the note and went to bed. I was called early that morning and had to get dressed and report to the nursing office. I don’t remember what I had to do—probably write a paper on why I shouldn’t sleep on duty. But it was embarrassing to meet with Maria Johnson, our director of nursing, and her assistant.

Nurses appeared different back in those days. Everything we wore on duty had to be white. If we didn’t look right we were sent to change our clothes. If we forgot to do anything that was expected of us, such as leaving a patient’s room untidy, we were called back on duty, dressed in our uniforms, to finish the task. Our director of nursing, Maria Johnson, always appeared very professional in her uniform. We used to say that she went to her quarters at noon and pressed her uniform, as it always looked as if she never sat down while wearing it. All of our supervisors were always dressed very professionally in their uniforms.

I think that most nights at the hospital the supervisor was the only licensed person on duty. The patient floors were staffed mostly by students. At night if a patient needed a narcotic, the nurse had to call the supervisor to get permission to give it. We were young students on at night, so we needed supervision. Miss Clara Wall, a supervisor, would ask every time we called for a pain medication, “Have you given the patient some warm milk and washed his or her face with warm water?” I thought, “Lady, I hope that when you get sick and in pain I’m here to bring you a wash cloth and warm milk.” We students would become smart enough to call her and tell her that we had washed the patient’s face, rubbed his back, and offered him some warm milk, but the patient was still in pain, so could we give a medication.

At the time I was in training, the hospital nursery had a census of between seventy and ninety babies because the mothers stayed in the hospital about seven days. We would take the babies in racks that held six bassinets out to their mothers every three to four hours. In between feedings we would diaper all of the babies and give them supplemental feedings if needed. There were many dirty diapers. One of the duties of the night nurses was to clean off the diapers that were used so that they could be sent to the laundry. It was a very stinky job in a small, stinky room.

We also had our turn in the formula lab. We had to make and bottle the formula. The rubber caps that were used on the bottles would make our fingers very sore because they were so hard to pull on the bottles and then take off when the nipples were put on. We did have fun working in the nursery. One RN, as she diapered the babies, would sing her song, “Don’t circumcise me if I don’t need it.” There were about twenty-one verses to the song.

My friend Marilyn Thompson and I were not twenty-one when we graduated and took the state boards, so we decided to stay at the hospital and work in the nursery until we could get our licenses. As RNs we could do more things, such as give the babies medications and gavage them. One of the fun things we did was to give the mothers a demonstration on bathing and taking care of a newborn. We’d choose the cutest baby to use for our demonstration. It was funny because we young girls who had never had a baby would sometimes be demonstrating to mothers who had several children. Another fun event was when we had a Jewish circumcision. The sun porch would be set up for a party. The rabbi would come and do the little surgery, and then there would be a party with lots of people and good refreshments.

About the time I graduated, the war was over, so there was no need to go into the service. I can remember when it ended. I was working on 7A—the top floor of the hospital. Looking down towards town I could hear the celebration going on. I spent the last few weeks of my training on 7A. It was the most expensive and nicest patient unit in the hospital. All the rooms were private and cost $10.00 per day. Most of the General Authorities were admitted to this floor when they were ill.

Edith Maurine Edwards Garrard

I was born July 4, 1924, in Salt Lake City, Utah, to David Samuel and Bertha Pearson Edwards. I was the eighth of nine children in the family, seven brothers and one sister. I lived all my life at the family home at 467 Eleventh Avenue until I was married. Of course, as a student nurse, I stayed at the LDS Hospital nurses’ home on Ninth Avenue and C Street during the three years I was in training. Those were three great years of knowing and working with exemplary people.

I was a cadet nurse who joined the Cadet Nurse Corps in December 1943 and graduated from the Groves LDS Hospital three-year diploma program in December 1946. I earned my bachelor of science degree in nursing from the University of Utah in June 1947. My graduation occurred after the cessation of World War II, so I did not join the active forces. Because I had attended the U of U prior to entering the nursing program, I discovered that I could earn my BS by June 1947 if I carried twenty-one hours in one quarter plus worked weekends to earn substance money. Several of my classmates did the same.

Although my father had initially opposed my becoming a nurse, the Cadet Nurse program provided an independent means of accomplishing this goal. There was no prouder father in attendance at the nursing graduation ceremonies than my father, who had acquired an entirely new perspective of nurses and the wonderful women who were my classmates.

Although my efforts did not qualify me for actively serving as a nurse during WWII, the Cadet Nurse program did provide me with the means to become a registered nurse, which had been a goal in my life. Shortly after graduation, I married an intern I met during training. He subsequently served two more years in the military.

Four of my brothers served in the military during World War II. The eldest was a West Point graduate who became a career officer and retired as a brigadier general. After the start of the war, the second brother joined the U.S. Air Force, became a pilot, and was later based in England and flew missions over Germany. The third brother joined the Utah National Guard at the beginning of the war and served for five years, assigned to multiple posts in the Pacific area as an artilleryman. The fourth brother was an eighteen-year-old young man drafted into the infantry who served and fought in the Battle of the Bulge. So you can see that my parents were deeply concerned when I decided to join the Cadet Nurse Corps. Had the war not ended when it did, there would have been five stars in the window. Fortunately, all of the military members of the Edwards family returned home safely. All were LDS Church members.

There was no central supply when I was a student. All nurses were expected to own a syringe and a variety of needles, which we carried in a container in our uniform pockets. The needles and syringes were carefully sterilized on a gas burner in a pan of distilled water. We were taught exacting sterilization techniques. I do not recall any injection site infections. Mrs. Mason, RN, diligently taught us isolation and sterilization technique. I do not recall many of us breaching these rules. I also do not recall nosocomial infections. The supervisors were diligent in requiring students to do things correctly and according to protocol. We students paid great honor and respect to our superiors. They were giants in our eyes. After graduation, when we all scattered to different locations, we all felt that our training had been excellent. Many of the graduates of the three-year diploma program went on with their careers and achieved much professional success.

Most of the students at the LDS Hospital then were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The LDS Hospital was across the street from the original Ensign Ward on Ninth Avenue and D Street. The students could not regularly attend weekly meetings because of the requirement to work many weekends and shift work. Most of us attended church when possible.

As nurses, we were taught to hold doctors in high esteem. We were taught to always show great respect in their presence. It was protocol to stand whenever a doctor entered the nurses’ station and to give him our chair if an empty one was not available. While making rounds with a doctor, a nurse always carried the stack of charts and made sure that the doctor entered the patient room first. The subservient attitude has continued to affect the lives of many student nurses of this era. We were also taught that we should always be ladies.

Like most of the other student nurses at LDS Hospital at the time, I was reared in a Latter-day Saint home where church activity was the norm and expected. My parents were good examples to me of what Latter-day Saints should do and be. This motivated me to gain a testimony and be an active Church member. This Latter-day Saint philosophy and belief was reinforced during our training. This was accomplished through more of an underlying teaching rather than by being actively required.

As students, our classmates became our very dear friends. In talk fests at night, we learned to cope with the traumatic and difficult experiences we encountered in our patient care. We were offered no professional psychological support system. Students carried tremendous responsibilities, and we lived by strict rules and regulations.

I have always been grateful for the Cadet Nurse program and the enrichment it brought into my life. In addition to the training I made wonderful friends. The Cadet Nurse program was wonderful!

During the inevitable difficult and emotional times that occur in a nursing career—as well as in the rearing of a family—I have received reassurance and strength from Latter-day Saint teachings and association with good people.

Margaret Maurine Harris

I entered nursing in August 1945 with the last group under the auspices of the Cadet Nurse Corps. At that time the war was coming to an end. We had only the minor inconvenience of rationing some items like shoes and sugar. At this time there was immense loyalty to our armed services, and we were happy to do what was needed. Some of my high school classmates joined various branches of the service, and we were very proud of them. My favorite woman high school teacher joined the WAVES. This was a time of intense patriotism. We were uniformed as cadet nurses complete with cap and a flowing cape.

At that time nursing was in a transition from the diploma-type nursing to collegiate. All cadets spent the first year at the University of Utah taking basic courses. The course was planned so that after the first year at the university, we would spend the next two and one-half years at the hospital that had accepted our application (LDS, St. Marks, or Salt Lake City General), and subsequently, we could spend an additional year to complete a BS in nursing if we so chose. During the last six months of our hospital experience, some could select to spend that time in a veterans hospital. About six of our classmates chose to do that and went to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

During the time we were at the University of Utah, we were housed at Carlson Hall. We tended to group with our hospital group. Though we were congenial, we banded together against any outside threat. Apparently our house mother sensed a difference between the nursing students and the others. She was heard to say, “You can take the girl out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the girl,” referring to the nursing students. Many of us were from small towns and small farming communities, and most of us would have to work to be able to pay our way through college. The Cadet Nurse Corps funded our education and gave us an allowance of fifteen dollars a month, which we thought was wonderful. That fifteen dollars gave us enough that we seldom had to ask our families for money.

Our instructors were very strict. We were on probation for the first six months, which meant that some would not make it past that point. Instruction was procedure-oriented, with each step in the procedure outlined in precise order. We used our mop bucket at home as a basin to practice bed baths. We practiced on each other, quizzed each other, cheered each other on, and listened to and consoled each other over the slightest mishap. The outside enemy—the instructors, the upper classmen, and the doctors who saw students as a curse—all caused us to band together in a tight survival mode.

The hospital could not have survived without the help of the students, as many graduate nurses who normally would be at the hospital were in the armed services. Nearly all of the graduate nurses in our hospital were the head nurses, supervisors, and teachers. That format was so standard that a graduate nurse who was just doing bedside care and not being some kind of administrator was suspected of not being up to par! Our teachers taught us the procedures, but when we were on our hospital wards we were under the direction of the RN head nurse on day shifts or an upper classman as the charge nurse on afternoon and evening shifts. The nursing care was done by the student nurses. The student charge nurses were under the direction of the supervisors, but there were only two to three supervisors for the entire hospital. When there were not enough senior students to be charge nurses for each shift, the responsibility fell to whichever students had the most experience on that ward in the hospital. Undoubtedly, it was because of the responsibility given to students early in their experience that the teachers were so strict with us, realizing better than we did what we were facing.

Because of the cohesiveness among us, we knew of the tiniest mishap. Any mishap seemed to loom large to the supervisors. Burned in my memory are such things as the time one student washed the thermometers in hot water and they had to be replaced. The philosophy seemed to be to pounce on the tiniest mistake as a means of preventing any larger ones that might be injurious to the patient. I do not recall any serious injury to patients by my classmates.

It was well understood that the patients’ welfare came first. We felt we had to be near death before we would call in sick. Any time a student nurse missed a day, she reported to the assistant superintendent of nurses for a review of the cause. The prospect of that interview was enough to cause us to want to “take up our bed and walk.” Any day missed because of illness had to be made up. Prior to graduation, all of the missed days were added up and had to be made up before a graduation certificate was issued.

Our service times were geared towards the needs of the patient. For some time we worked the famous split shifts working from 7:00 a.m. till noon to take care of the morning bathing and care of the patient and then returning from 7:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. to prepare the patient for bed, which included a back rub, straightening the bed and room, and any treatments or other care needed. For a time we worked this split shift until a rule was made (by the State Board of Nursing perhaps?) that our assigned time had to be completed twelve hours from the time we began. Hence, the change was from 7:00 a.m. till noon and 4:00 p.m. till 7:00 p.m. We thought that change was marvelous. In the afternoons we had our classes, and then our study time was after 7:00 p.m. When we worked the night shift, we slept from about 8:00 a.m. till lunch and then went to classes in the afternoon. It was often hard to stay awake for classes.

I remember this time mostly as a time of intense feelings of loyalty and pride in our country, a time that caused all of us to work together for the good of our country. The nursing program was tough. We were disciplined and learned to put our patients’ needs first and to depend on each other and help each other. As a result we learned many skills that have been valuable throughout our lives. Also, we have bonded as friends, which is as much felt and alive today as it was during our times together in the Cadet Nurse program.

Mary F. Hughes

Despite the fact that I have not been actively engaged in the field of nursing for the past twenty years, I always have a feeling of excitement when I go into a hospital. It comes upon me suddenly. As I see people scurrying about I feel a sense of direction, a feeling of commitment, and oftentimes the tenseness of urgency. If I search the individual faces that are about me, I see joy, happiness, anxiety, despair, and a myriad of other emotions. I walk through the corridors and cannot help but look into the rooms with open doors, for I know that in these rooms, human drama is being played out. The closed doors, especially those forbidden to the public, hold a particular fascination for me, and I am always curious as to what might be happening behind those doors.

Nineteen forty-four was an exciting year. World War II was in full swing. The war was foremost in all our minds and lives as we heard about battles on far away shores. Our eyes would scan the evening newspapers for war casualties, fearing to find a familiar name. Everyone was doing their bit to aid the war effort, and I, eighteen years old and a new high school graduate, was preparing to enter into the United States Cadet Nurse Corps.

There were not many career options open to young women at that time, and the realistic choices boiled down to three: becoming a school teacher, a secretary, or a nurse. It was not a difficult choice for me, as the visions in my head of nursing, especially at the time of war, held the promise of great adventure. An additional benefit was the opportunity to leave home, spread my wings, and see what the world was all about. The financial help offered through the Cadet Nurses program—tuition, housing, and a fifteen dollar per month stipend—had also given me more than a gentle nudge towards the profession.

After much consideration, I chose the Salt Lake County General Hospital as my place of training. The hospital was located in Salt Lake City, Utah, some fifty miles from my home—a nice safe distance that would allow me the independence I wanted while still being close enough for a visit home when things got tough. The county hospital, as it was known, was operated primarily to provide medical care for the indigent and operated on a bare-bones budget with no frills. It was a training ground for University of Utah medical students, and the Salt Lake County General Hospital nursing program was in turn affiliated with the university. Upon my completion of the three-year prescribed course, I would receive not only my diploma but university credit for course work as well.

My first six months were spent living on campus at the University of Utah along with fellow cadet nurses from three other area hospitals. We all lived in the same dorm and took the same courses. We carried eighteen hours per quarter studying chemistry, anatomy physiology, foods and nutrition, library science, English, and other basic subjects.

It didn’t take my classmates and me long to discover the fact that eighteen hours was a hefty load to carry, but it also didn’t take us long to discover the fun and antics of dorm life and the excitement of life in the big city. There were trolley rides into town and excursions to an army base nearby to dance with men stationed there. When money was scarce, which was often the case, long walks about campus and the surrounding areas filled the few hours that were left.

We were a unified group, although at the end of the six months on campus, we knew we would separate for our various hospitals to continue our training. We felt we were doing our part to aid the war effort and were eager to get on with the business of becoming a nurse. The time went by quickly, and January found us at our respective hospitals, where we were to be “probies.”

Our first challenge was to get settled into the Nurses’ Home. This was a big three-story building sandwiched between the various other buildings that made up the hospital complex. It was where we would sleep, eat, attend classes, study, socialize, and commiserate with each other.

We probies were assigned rooms on the top floor with the expectation of moving down to the lower floors as we gained seniority. I shared my room with two other roommates. Our particular room was tucked away in the corner of the old building and appeared to have been forgotten for some time. It was my bed that I remember most vividly. It was an old, discarded hospital bed. It seemed to be a mile high, and I soon found out I was in deep trouble because my curves matched the ruts that were worn into the mattress.

Our indoctrination into the life of a probie was not a gentle one as the many rules and regulations were laid out for us by the housemother. She informed us that we were to be accountable to her for all our comings and goings. There was nightly curfew of 9:30 p.m., which would be strictly enforced. We were, however, allowed two late passes (12:00 midnight) per week, and two overnight passes per month could be substituted for the late passes if approved by the housemother. We were advised to sign out and to sign in, and we were told that any late violations would result in giving up passes for an extended time. The housemother ruled with an iron hand, and we soon found it difficult to slip anything over on her. The doors were locked at midnight, and the worst possible scenario was to be late and to have to ring the doorbell, knowing she would answer it.

The next indoctrination was that of the dress code. We were all excited when we received our six white uniforms with a cadet nurse patch on one sleeve. White stockings and oxfords would complete the uniform until we could earn our coveted cap. The hospital laundry would wash and starch our uniforms. They certainly did a good job—our uniforms often resembled cardboard boxes as we slipped into them after they were freshly laundered. No jewelry was allowed, and the necessary watch, along with any rings, were to be pinned to the uniform. Incidentally, a few engagement rings were confiscated because this rule was not adhered to. Others followed the rule, and a few engagement rings went through the laundry still attached to uniforms. Our hair was to be neatly done and kept off our collars in a net. We were cautioned that under no circumstances were we allowed on the hospital floors unless we were in full uniform. We were also given the option to purchase a coat. We thought this ankle-length cape, made of dove-grey wool and lined with red, was a splendid addition to our uniforms and was well worth the three months’ stipend it took to pay for it.

Somewhere along the line, we were also given a Cadet Nurse Corps dress uniform. It was a sharp-looking uniform made of grey wool complete with silver buttons, epaulets, and of course, the cadet nurse patch on the sleeve. A jaunty grey beret completed the ensemble. There was no definite use for the uniform, but it was fun to wear and made us feel like we were very much a part of the war effort.

Our next three months were spent on probation, a time designated to prove ourselves. Our status as probies was mighty low in the medical hierarchy. We were advised of the propriety of standing whenever a physician approached us. We were also to show respect for our instructors by arising as they entered the classroom.

Our first experience on the floor was cleaning units. This included cleaning everything used by the former patient, right down to the bed springs. From this somewhat tedious task, we progressed to the bedpan detail and then on to the finer arts of nursing.

Our pharmacology course was strictly a no-nonsense affair. Our instructor was a stern taskmaster, and we were drilled over and over about the importance of aseptic technique and the responsibilities of administering medications. This training has served me well. After almost fifty years, I am still an avid label reader, and any lids found on my kitchen countertops are always upside down.

Finally, most of us had endured probiehood, and we were anxious for our capping. This solemn and impressive ceremony was held in a local church with proud family and friends gathering for the occasion. It was a treasured moment for me as I marched down the aisle, holding a single red rose, and my coveted cap being placed upon my bowed head by the superintendent of the nurses.

I still have my cap tucked away among other cherished mementos of times gone by. I am still very proud of it. I worked hard to receive it, and it was a badge of honor for all to see as I entered into the weighty responsibilities of nursing.

By 1943, military service had taken many of the registered nurses, and few were available to staff the hospital. There were few auxiliary people as well. Student nurses furnished the bulk of the manpower needed to keep the hospitals functioning during those crucial years.

Nurses’ aids were unheard of at that time, and there was one male orderly serving the entire hospital on each shift. Possibly half of the wards had RNs as head nurses, and senior students assumed this responsibility on the other wards. There was usually one RN house supervisor for each shift to cover the entire hospital. If one was not available, senior students substituted. The hospital consisted of a medical infirmary (extended care) building, a surgical building, and an obstetrics facility. The OB facility housed the delivery room, newborn nursery, antepartum, postpartum, and gynecological wards. In addition, across the block there was a communicable disease unit. One wing was for children, while the other was a venereal disease treatment center. There were no enclosures connecting the various buildings, and the house supervisor really had a lot of territory to cover.

My first assignment was on a surgical unit, and, with my cap proudly perched upon my head, I was inducted into the real world of nursing, and once again it was not a gentle induction! After three weeks of working days, I was assigned the night shift. We rotated shifts at the discretion of the head nurse and each rotation lasted a week. My first week of nights still holds great horror for me.

Surgery II was an eighteen-bed surgical female unit. There was one large ward with six beds up one side and six down the other. At the other end of a hall was a porch with three more beds. Three private rooms plus the nurses’ station were along the hall which connected the two. I was placed on the unit alone with a full census.

The patients were varied. There were no post-op recovery rooms or intensive care units, so we were responsible for all levels of care. I had a patient who spiked a 104 degree temperature each morning around 4:00. To add to this, she had a gastric tube connected to a Wangensteen suction, which was a challenge in itself. The Wangensteen suction was a monstrosity of an apparatus made of three discarded IV bottles. These were connected together by IV tubing in such a manner as to create a gentle suction when water was drained from one bottle to another, with the third one catching the drainage. The first trick was to set it up correctly; the next trick was to keep it working by keeping the lines free and the water level right by interchanging two of the bottles. If this sounds complicated, it was—much different than plugging into the hospital suction system.

I had a ninety-year-old woman with a fractured hip. She was in a spica cast, which covered her from the waist down, and she needed frequent turning throughout the night. The other patients were in various stages of post-op recovery, with a few next-day surgeries thrown in.

About mid-week, a two-year-old child with a skull fracture was admitted to the ward during the early morning hours. His condition was critical, and the physicians didn’t want to risk moving him to the pediatric ward, which was on the first floor of the medical building three-fourths of a block away. I had no training in pediatrics thus far, and I still remember how ridiculous the adult-sized blood pressure cuff looked on his small arm. Somehow, my patients and I managed to survive the week, but it was a week in my life that I will never forget!

The responsibilities of student nurses were many. In addition to patient care, we cleaned beds; folded and stacked linen; and cleaned and wrapped IV tubing, catheters, treatment trays, and whatever else was around for autoclaving. We sharpened needles, boiled syringes, and kept the treatment rooms clean. Today everything is expendable. In those days everything was in short supply and was used indefinitely.

Keeping the nurses’ station tidy, as well as straightening the various shelves and drawers about the ward, was the responsibility of the night nurse. Then there was the nightly ritual of soaking the bedpans in Lysol solution. This was done by placing the bedpans in the one and only bathtub, filling it with water, and swirling some Lysol around.

While on our operating room rotation, we took turns on call. During our time on the obstetrical and gynecological floor, a combined unit, we did the same. There was never any make-up time given for the sleep we lost fulfilling these responsibilities. The student nurse in the operating room on the 3:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. shift was responsible for all the supplies and for autoclaving all the surgical packs for the entire hospital. In addition, she pulled the instruments for the next day and visited the surgical wards with a razor in hand to prep the patients for the next day’s schedule.

During our senior year, we were given the opportunity to assume head nurse responsibilities—that is, if we were lucky enough to pull day shift, which didn’t happen very often.

In the diet kitchen, we were responsible for the special diets. We planned and cooked the food, set up the trays, put them on the carts, and personally delivered the trays to the patients on the floor. We were in the kitchen by 6:00 a.m., worked until after the noon meal, had a few hours off in the afternoon, and then went back to the kitchen to prepare the evening meal.

Well, somehow I survived the rigors of being a student nurse during the World War II era. The war ended, I graduated, married, had children, and worked in the profession for twenty years in a variety of capacities.

The advances in nursing and the medical field in general have been tremendous, and I have witnessed firsthand some exciting breakthroughs. It was during my student years that penicillin was introduced, and little did anyone realize the impact this discovery would have on the world. It came to us in crystalline form, and we would dilute it with normal saline as needed. It was given to patients IM every three to four hours around the clock, often with dramatic results. One such case comes to mind.

Tucked away on the third floor of the surgical building was a small private room occupied by a dentist who had been hospitalized for treatment of osteomyelitis of the spine. The room was not a particularly pleasant one to enter. It was filled with clutter. Reading material was stacked so high on every flat surface that it was a challenge to find enough space to place a food tray. As student nurses started their rotation on the floor, they were warned of how crotchety this doctor could be. Everyone knew that he had every right to be, for he had been in this tiny room for over seven years as the disease ravaged his body. He had undergone multiple surgeries as surgeons attempted to cut away the diseased bone, but the disease and the agonizing pain continued, robbing him of his health, his livelihood, and his will to live.

The advent of penicillin brought him new hope. It was known as the miracle drug, and it was not misnamed. Within a few months after treatment was started, the doctor left his tiny cubicle and returned to his home and eventually to his practice.

My first orientation as a student to psychiatric nursing was two dark, dungeon-like rooms in the basement of the surgical building of the old county hospital. These two rooms served as a holding place for patients awaiting commitment to the State Mental Hospital. It took all the courage I could muster to take food and medications to those being held there.

In the mid-fifties, I worked the 3:00 to 11:00 shift as a charge nurse on one of Salt Lake City’s first psychiatric wards in a private hospital. The thirteen-bed unit was a far cry from the two rooms in the basement of the county hospital. For the most part it was a pleasant place to be, but many patients were restrained. Although restraining patients was not a pleasant task, there often was no other way to control abusive and destructive behavior. Electric convulsive therapy (ECT) and insulin shock therapy were often the choice of treatment. Lobotomy was also a distasteful method of patient control, one which carried lifelong ramifications for the patient and family.

Midway through the three years that I worked on the unit, tranquilizing drugs made their appearance. Thorazine was the first, with resperine close behind. When I left the unit, restraints had been thrown away, insulin shock therapy was no longer used, and ECT was rapidly losing popularity as a mode of treatment. What a wonderful breakthrough!

Over the years, I myself have felt all the emotions mentioned above. I have experienced the joy of hearing the first cry of my newborn babies. I have peered through nursery windows, feeling great awe as I saw a new grandchild for the first time. I have felt the pain of surgery and have welcomed the soothing touch of a hand upon my cheek. I have waited long, lonely hours outside the operating room, for the words “all went well.” I have experienced the anxiety and despair of seeing my husband and daughter hover near death, and I remember how good it felt when I wheeled them out of the hospital, knowing they had another chance at life.

Through all these experiences, I have enjoyed seeing nurses at work. Oh, how proud I am of the nursing profession today. I am amazed as I observe their skills. I thrill as I see them manipulate the high tech equipment with ease and knowledge. I applaud the fact that they are no longer seen as mere handmaidens for the physicians but are now viewed as thinking, competent individuals who have much to offer the medical field in their own right. I admire their spunk, their confidence, and their eagerness to be heard. Equally as important, I am gratified when I see and feel their love and compassion for those who need their care. Yes, I really do enjoy seeing nurses at work, and as I watch, my mind often slips back over the years to June 1944.

As I watch nurses at work today, I envy the modern conveniences and technology they have at their fingertips. I admire their fine-tuned skills and their vast reservoir of knowledge, and I am very proud of their expanding role in the medical field. And now, if I may, I would like to extend a word of advice to nurses today. Pursue your goals. Strive to expand your role and continue to command respect. However, do not get lost in the modern world of technology. Do not relinquish to others your rightful place at the bedside of the patient. Be there to extend a soothing touch to those in pain. Be there for the lonely and frightened. Be there to offer gentle words of encouragement to those in despair. Be there to listen, to understand. Be there to offer solace to the distraught and grieving. Be there to comfort and to care.

As you carve the role for future nurses, fiercely guard the unique nurse-patient relationship that is yours. Recognize its healing power, for it is one of the most powerful tools you have to enhance the healing process. Cherish this relationship. It is your heritage handed down to you from past generations. Remember it is yours to pass on to those who will follow in your footsteps.

Joyce Gottfredson Johnsen

Joyce Gottfredson Johnsen

As a little girl, I always wanted to become a nurse. My father, David B. Gottfredson (physician, surgeon, and family practicioner in Richfield, Utah), would sometimes let me go to his office to help in the morning. He and the family were in Richfield from 1928 to 1941. He was called up with the Utah National Guard for World War II, and the family became “camp followers.”

Our June 1943 nurses class was the first cadet nurse class to go all three years through the program. Those already in the nursing programs of the several Salt Lake hospitals were signed up into the program for the balance of their training, as desired.

It was at County (Salt Lake County Hospital) that the University of Utah Medical School had its beginnings, giving us trainee nurses additional opportunities to observe the medical students in training and to be taught by specialists in their medical professions. County also had special wards, or departments, for communicable diseases, the elderly, and prisoners, along with an out-patient department and clinic. The communicable diseases ward was a good learning experience. During the polio epidemic, we were involved in caring for polio patients on the several polio wards. I was also aware of a diphtheria patient and a whooping cough patient while in training. In the medical ward building, there was an old folks area, where we administered medicine as part of our service on the upstairs medical ward. (The old folks had their own attendants to help them.) Also, downstairs there was a jail ward for prisoners in locked cells. If we needed to attend to them, we would take a male orderly with us to go down there. Sometimes there would be psychiatric patients in the locked area. In the outpatient department and clinics, we had the experience to care for patients with tuberculosis and venereal diseases, as well as do well-baby, maternity, and follow-up care and nutrition counseling.

One thing I remember from my cadet nurse training days was the hard, long, marble floors down the hall from the nursing supervisor’s office in the main building. There was a ward there at the end. I was caring for an elderly black man in the final stages of venereal disease. His mind had been affected and his teeth were badly deteriorating. My perception of what happened was that he chewed on his teeth, then spit the debris at people, including me.

On a surgical ward, a transient had been admitted for an emergency appendectomy in the afternoon. I was on the 3:00 to 11:00 shift alone, and in the early evening as patients were put to bed, the transient wakened from the anesthesia. He was determined to leave—to get out of “this house of ill repute”—new stitches and all. I don’t remember for sure, but he somehow was getting over the edge of the bed rails. I finally was able to get some help to restrain him.

The only time I experienced sickness (nausea and queasiness) was during an amputation by Dr. Cyril A. Callister. When I was asked to hold the basket to receive the amputated leg, my stomach really began churning.

During my three-month internship (the last three months of training) when I was acting night supervisor, I received a phone call from one of the student nurses on duty on the medical 3 ward. One of the patients was having some distress. From what she described, I told her to check his blood pressure, and I would come to the ward to see him. I then phoned the doctor on call to report to him and requested that he come to see the patient. After several additional calls to the doctor and several more BP checks, the man settled down some. The doctor didn’t ever come. At rounds next day, as reported to me later, this on-call doctor was read the riot act by Dr. Wintrobe, because the patient had had a heart attack.

Our class finished June 12, 1946, with seventeen graduates. Our three-class graduation was not until September 3, 1946, 8:00 p.m.—The thirtieth annual commencement exercises. It was in the old Union Building first floor hall—the building just west of Kingsbury.

Class motto: “servamus fidem”