Into the Twenty-First Century—2000 to 2019

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Into the Twenty-First Century—2000 to 2019," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 379–410.

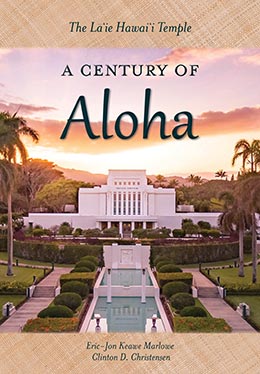

Views of the 2010 Hawaii Temple open house, a tradition that started ninety years earlier at this very temple. A staging area in the parking lot was arranged to accommodate nearly 43,000 visitors. Photos courtesy of Monique Saenz.

Views of the 2010 Hawaii Temple open house, a tradition that started ninety years earlier at this very temple. A staging area in the parking lot was arranged to accommodate nearly 43,000 visitors. Photos courtesy of Monique Saenz.

With the dedication of the Kona Hawaii Temple, the Laie Hawaii Temple district was reduced by a handful of stakes to its east but still reached thousands of miles west into the Pacific. In the following year, temple excursions continued from the Marshall Islands, and a group of Saints from Guam made the long journey as well. Also, new languages, such as Mongolian, continued to be added to the Laie Hawaii Temple’s long list of available translated languages, which included Korean, Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, Marshallese, Kiribati, Samoan, Tongan, and others. As temple matron, Sister Clarke marveled at the diversity of temple workers, which she referred to as “a beautiful tapestry of cultures.”

They were a mixture of sisters whose roots extended far beyond the islands of Hawaii. Among our workers were those whose names were Chen, Wong, Chang,—Yamaguchi, Yoshimura, Matsuzaki, Kim, Lee, Hee. And our Polynesian sisters: Kahalehili, Niutupuivaha, Kamauoha, Soliai, etc. Then there were our marvelous young student volunteers from the university,—Ina Dapalongga (Indonesia), Subashini Chandreskera (Sri Lanka), Chemge Dugasuren (Mongolia), Joy Chew (Singapore), Lorena Arroz (Philippines) and our darling Junko Tsakaguchi (Okinawa); beautiful, outstanding young women. . . . We loved them all most dearly.[1]

On 1 November 2001, the Clarkes were released and Glenn Y. M. Lung and his wife Julina began their service as temple president and matron. President Lung was born in Hawaiʻi to Chinese parents who had joined the Church in the 1940s. His love for the temple was influenced by his father, a Confucianist who loved genealogy and was drawn to the Church because of his interest in connecting families. Being of Hawaiian, Asian, and American descent, Julina Lung was deeply connected to the temple’s past. Her mother, Lottie Ching, had sung in the children’s session of the temple dedication in 1919. Even further back, her Hawaiian great-grandfather, Samuel K. Imaikalani, and his wife Makaweli moved to Utah to be closer to a temple; he died in 1892 as a resident of the Hawaiian colony in Iosepa. Julina was named after her grandmother Julina Imaikalani, born in 1885 in Hawaiʻi and delivered by Joseph F. Smith’s wife Julina Lambson Smith.[2]

The Lungs were called suddenly on 4 October 2001 and began their service less than a month later. Though both loved the temple and commonly attended, neither had served as a temple worker. Sister Lung recalled that when they had a question or needed to know how something was to be done, they would “go look at the handbook.” Then she added, “It would be in there. I’m telling you, the Lord put it in there.” The Lungs further credited an “excellent” temple recorder, Wayne Yoshimura, and temple engineer, Carl Tuitavuki. “They kept us going. I mean anything came up, and they could advise you.”[3]

Though generally behind the scenes, these two positions—temple recorder and engineer—play an invaluable role in any temple’s success. The engineer generally ensures the maintenance of physical aspects of the temple such as the physical plant, structure, decor, furnishings, safety and security, and landscaping. The appointment of temple recorder is often less understood. Wayne Yoshimura, who served as temple recorder for over fifteen years, explained that a recorder in general assists the president in overseeing the day-to-day operations of the temple. As suggested in its name, the temple recorder specifically ensures the ordinances are performed and recorded accurately (see Doctrine and Covenants 128:1–4). Additionally, the recorder may oversee temple finances, reports, paid employees, budgeting, and more. Though several of these tasks are seemingly secular, Yoshimura emphasized that in the temple they always serve a spiritual purpose.[4]

Beautification of Hale Laʻa Boulevard

A project to renovate Hale Laʻa Boulevard from the ocean up to the Laie Hawaii Temple began in 2003. R. Eric Beaver, president and CEO of Hawaii Reserves, which manages Church land in Lāʻie and oversaw the project, said the beautification of Hale Laʻa Boulevard was “to extend the beauty, character and influence of the temple through the community, out to the highway, and to the water’s edge.”[5] At the groundbreaking ceremony on 25 October 2003, President Gordon B. Hinckley prayed that those who drive along Kamehameha Highway would be inspired by the beauty of the boulevard “to come and go about the [temple] grounds.”[6]

![President Gordon B. Hinckley expressed his hope that “thousand, hundreds of thousands, even millions of people . . . [would] look up this lovely street to the temple, and have come into their hearts some acknowledgment that this is a special place—a place of beauty, a place of faith, a place of God.” Photo by Daniel Ramirez courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://creative commons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode.](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/6846/Laie_Hawaii_Temple_August_7_Page_406_Image_0001.jpg) President Gordon B. Hinckley expressed his hope that “thousand, hundreds of thousands, even millions of people . . . [would] look up this lovely street to the temple, and have come into their hearts some acknowledgment that this is a special place—a place of beauty, a place of faith, a place of God.” Photo by Daniel Ramirez courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

President Gordon B. Hinckley expressed his hope that “thousand, hundreds of thousands, even millions of people . . . [would] look up this lovely street to the temple, and have come into their hearts some acknowledgment that this is a special place—a place of beauty, a place of faith, a place of God.” Photo by Daniel Ramirez courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

The project included removing the seventy-foot Norfolk pines that previously lined the boulevard and replacing them with stately Cuban palms. Blue rock walls were added along either side, with new sidewalks, curbs, and streetlights. A parking lot was built across from Lāʻie Elementary School and Temple Beach, a traffic circle was installed near the temple, and an enclosed meditative garden was created on the beachfront. The overhead electrical and utility wires on both ends of the boulevard were buried to create an open view to the ocean, and the entire length of the street was relandscaped.[7] Upon the project’s completion, Beaver said, “The beauty of the project exceeds all of our expectations and sets a new aesthetic standard for the community.”[8]

At the same time, a new front entrance to BYU–Hawaii and a low wall along the front of campus were made of the same blue rock that adorns Hale Laʻa Boulevard. Of the connection of these dual beautification projects, BYU–Hawaii president Eric B. Shumway said, “They will accentuate the spiritual and eternal purposes of the Temple of God and of the University of the Lord in Laie. Indeed, they will please the eye, they will gladden the heart, and they will also lift the soul.”[9]

At the project’s dedication on 11 December 2004, President Gordon B. Hinckley reminded everyone that “the very name of the street we dedicate [Hale Laʻa] denotes ‘sacred house, house of the Lord,’ in the beautiful Hawaiian language.” He hoped the improvements would enhance Lāʻie’s tradition of being a place where Latter-day Saints and others can “find refuge from the noise, the conflict, [the] distress . . . of modern living, here to find peace, here to commune with the Lord, here to enter into His sacred House and partake of the holy ordinances.” He expressed his desire that the “thousand, hundreds of thousands, even millions of people who travel up and down Kamehameha Highway—may slow down and look up this lovely street to the temple, and have come into their hearts some acknowledgment that this is a special place—a place of beauty, a place of faith, a place of God.”[10]

Concurrent with the beautification of Hale Laʻa Boulevard and the entrance to BYU–Hawaii, the temple visitors’ center closed in June 2004 for some significant renovations as well. These included several state-of-the-art interactive kiosks and updated displays able to accommodate multiple languages, as well as the redesign of the east theater to enable the showing of large-format movies such as The Testaments.[11] In 2005 various aspects of the temple grounds were reworked to tie in to the recently completed Hale Laʻa Boulevard project, including the replacement of some of the old sago palms with new royal palms.[12]

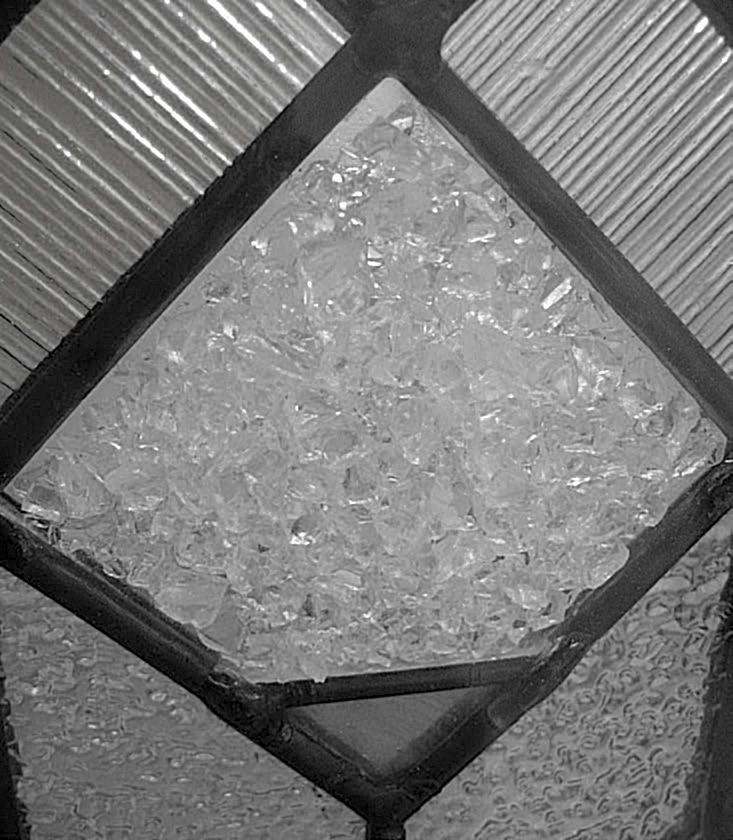

Designed by the original architects to represent the tree of life (a symbol of Christ), the stained glass windows encircling the upper walls of the celestial room were restored in 2005. Courtesy of Tom Holdman.

Designed by the original architects to represent the tree of life (a symbol of Christ), the stained glass windows encircling the upper walls of the celestial room were restored in 2005. Courtesy of Tom Holdman.

Finally, in 2005 the stained glass windows were restored. Designed in a tree of life motif by the original architects, they encircle the upper walls of the celestial room. Each window is about nineteen inches wide and forty-eight inches tall. In the earlier years, the windows were kept open for ventilation, and they became deeply corroded. Stained glass expert Tom Holdman removed 154 fragile pieces of stained glass from each of the twenty-four lead frameworks, and then he carefully cleaned and restored the nearly 3,700 beautiful pieces of glass before placing each piece back into the repaired frameworks.[13]

Remodeling the Temple, 2008–2010

When the Hale Laʻa beautification project was near completion, the Lungs were released and Wayne and Bernice Ursenbach began their service as temple president and matron on 1 November 2004. It had been over twenty-five years since the temple last underwent a major remodel, and after his first day of service President Ursenbach knew he was there “to get the temple operating properly and to work towards getting the temple remodeled.”[14] Over several months of working with the temple engineer and recorder, President Ursenbach submitted recommendations to the Temple Department that the baptistry, foyer, art windows, and various other aspects of the temple be modified. In particular he noted that the baptismal font was too small (a concern noted by President Heber J. Grant upon his inspection of the temple in 1919) and that water would at times flow over the sides during the ordinance.[15]

Experts were sent to evaluate the temple, and upon further inspection identified some seismic issues with the structure’s outer wings. As the temple presidency changed, President Ursenbach told his successor, H. Ross Workman, that there were some serious problems with the physical condition of the temple. In 2008, thirty years after the temple’s last major remodel, President Workman was notified that the temple would close for extensive renovation.[16] John Stoddard, Temple Department project manager, later described how several projects evolved into such a major remodel: “The original work order for the Laie Temple Renovation came . . . in November of 2006. At first the Temple underwent a seismic study, then it grew to become handicap accessible, and then a list of deferred maintenance problems was tacked on to the project, and the question arose, ‘What do we fix, and what do we not fix?’ President Monson said, ‘Do what is right for the Temple.’”[17] The official letter from the First Presidency stated that the closure was “necessary to return the Temple to its original beauty, and to bring it up to current Temple standards.”[18]

The renovation called for the preservation of murals and various internal features; demolition of the front canopy and interior space of most rooms; and the removal and reinstallation of all electrical, mechanical, HVAC, and operating systems. The exterior and interior finishes were to be stripped down to the bare wall, existing roof and drainage systems replaced, and the baptismal font enlarged. All training rooms, locker rooms, and restrooms were to be renovated. New front and rear entrances would be constructed with improved access for those with disabilities. All exterior and interior walls were to be refinished, and new carpeting, wall coverings, moldings, fixtures, furnishings, and decorations would be installed. Finally, all exterior sidewalks, rails, and benches were to be replaced, the grounds relandscaped, and the parking lot repaved.[19]

It was also decided to restore elements that were reduced or lost in previous remodels. For example, some of the narrow windows on each side of the temple core had been covered over, and it was decided to restore them, bringing much more natural light into the temple.[20]

Demolition began in January 2009. “Our instructions were simple,” said crew member Zack Taylor. “No food or drink inside the building, no salvaging, and no swearing. We were then handed jackhammers, crowbars and power tools in order to take the temple from a house of worship and transform it back to the construction site that it was ninety years earlier.”[21] As part of this process, all layers of paint on the temple were completely stripped down to bare cement walls, leaving the gray shell of the temple exposed. Senior architect David Brenchley said, “After we had removed a lot of the finishes, we were extremely surprised at how well the structure had held up. There were just a few areas we had to repair. The majority of the original structure and a lot of the detail on the exterior is in great condition. It’s a wonderful building.”[22] Construction superintendent Bruce Bean noted, “It became apparent the builders in 1915 were truly remarkable craftsmen and in a class of their own. It is amazing how true and aligned the Temple is.”[23]

Baptismal font

Laie Hawaii Temple baptismal font, 2010. © IRI. Used with permission.

Laie Hawaii Temple baptismal font, 2010. © IRI. Used with permission.

During renovation, the baptismal font underwent extensive changes. As mentioned, the original brass font was considered too small and the platform surrounding it was too narrow. Thus plans called for constructing a bigger concrete font, enlarging the platform, removing one of two stairways, and preserving the original twelve oxen. However, the redesign of the font turned out to be too big for the pedestal that rested on the backs of the oxen. Of this problem it was recorded: “Contractors used a considerable amount of time and inspiration to devise a new plan that would work after shaving down the existing pedestal. . . . With a simple measuring tape, screws, string and a pencil they hand-drew an ellipse for the shape of the new bowl and cut the elaborate wooden form pieces. . . . They [then] suspended the assembled pieces above the base to ensure the proper thickness of concrete in the space beneath.”[24] Finish work was done using photos from Church Archives as a model to restore the baptismal font as closely as possible to its original design. Last, custom-formed glass panels were installed around the font.

In the end, the only parts of the original baptismal font that remained were the sculpted oxen created by Avard and Leo Fairbanks in 1916 and 1917. The oxen are not pointed in the four cardinal directions as they often are in other temples, because the space available would not allow it.[25] There is, however, a brass arrow located in the floor that indicates true north.[26] Interestingly, it was discovered that the sculpted grass and reeds around the oxen were once painted green and gold, rather than the pure white they were at the temple’s closing. To restore authenticity, the grasses were again painted green and gold.

Glass art

Glass artist Tom Holdman had restored the original celestial room windows five years earlier and learned that they were a representation of the tree of life. Called back to work on this renovation, he explained that “early on, it was decided the theme for the art glass in this Temple would denote the paradise of God, and partaking and sharing of the Tree of Life.” Approved design elements included the hibiscus flower and the kukui tree.[27] The yellow hibiscus is the Hawaiʻi state flower. Its design “is found in the foyer to give the feeling that you are entering into the Lord’s paradise and can be at peace.”[28]

Before this remodel, patrons accessed the upper rooms of the temple by a stairway passing through the baptistry. During the renovation this stairway was sealed off using, in part, glass art depicting the kukui tree. Holdman explained:

The Baptistery glass is a Kukui tree—a reminder [of the] Tree of Life, or Jesus Christ. The tree was chosen for its historical significance in the Hawaiian culture. The various parts of the tree had many uses and, in particular, the oily nut was used as a lamp to bring light for hundreds of years, as well as creating clarity on the water to improve vision for the fisherman. The stained glass tree also has exposed roots and it appears as if the roots and branches are weaving together, just as we weave our ancestry and posterity through Temple work. In addition, the tree has twelve pieces of fruits reflecting the scripture in Revelation 22:1–2 “. . . on either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits . . . and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.”[29]

Describing his effort to preserve and honor the past, Holdman continued:

I felt moved that a piece of the original Celestial Room needed to remain, so I asked that the old chandelier be shipped to my studio. I crushed the crystal like the early Saints crushed their china and crystal to adorn the walls of the Kirtland Temple. The fine crystal pieces from the old chandelier were then added to the stained glass window designs of the doors to the Celestial Room. This helps us remember all the sacrifices the Hawaiian pioneer Saints went through to build the fifth temple in the Church.[30]

Glass art depicting the kukui tree (chosen for its historical significance in the Hawaiian culture) was added to the baptistry to emphasize the theme of partaking and sharing of the tree of life. © IRI. Used with permission.

Glass art depicting the kukui tree (chosen for its historical significance in the Hawaiian culture) was added to the baptistry to emphasize the theme of partaking and sharing of the tree of life. © IRI. Used with permission.

Holdman concluded: “I really tried to listen to the Spirit and glorify God through the art glass of this, His holy Temple, for the beautiful people of Hawaii and Polynesia. The ultimate experience for me came after all the hard work and sacrifice of creating the windows when, in the Celestial Room, the Spirit came upon me and whispered that the Lord had accepted my offering to Him.”[31]

Interior design

Consistent with symbolism in the windows above, glass art in the doors of the celestial room also depict the tree of life—a symbol of Christ. In honor of those who sacrificed to build the original temple, pieces of the original celestial room chandelier were crushed and then added to the designs of the celestial room doors. © IRI. Used with permission. Inset photo courtesy of Tom Holdman.

Consistent with symbolism in the windows above, glass art in the doors of the celestial room also depict the tree of life—a symbol of Christ. In honor of those who sacrificed to build the original temple, pieces of the original celestial room chandelier were crushed and then added to the designs of the celestial room doors. © IRI. Used with permission. Inset photo courtesy of Tom Holdman.

The Temple Department asked interior designer Greg Hill “to take a more historic angle on this renovation.” Hill explained: “I have tried to bring in the feeling of the Hawaiian culture, the islands and the South Pacific. . . . We’ve done this in the wall coverings which depict tropical ferns, in the floral implementations in the fabrics, and the wood which represents the koa tree.” Hill added that “probably more so in the Laie Temple, than any other Temple, you will see artwork of Hawaiian landscapes, seascapes, and rainforests. . . . There is no question that as you move from room to room that you are experiencing the sacred ordinances . . . in a setting that is very Hawaiian.”[32]

The bas-relief models of the friezes were removed from the chapel and hung in the lobby and then beautifully lit to give “a striking presentation when you enter the Temple.” Hill concluded: “Thoughts and impressions have come to me regularly: Over the two weeks as I laid out the furnishings, I have been prompted to move pieces of furniture and art numerous times. And, I feel that the end result brings us closer to what the Lord wants.”[33]

Decorative painting

In his effort to return the temple to its original form, decorative painter Aaron Allen considered the craftsmen who originally built the temple between 1916 and 1918 and asked, “What would they have done if they had the opportunity, budget, time and tools?” And of selecting patterns for each room, he stated: “We made sure they came from sources that were available then . . . [and] could have been used then if more time and opportunities had been in place. With those thoughts in mind, we were able to bring out more detail.”[34]

Millwork in the celestial room ceiling presented a particularly rich opportunity. The wood moldings had been carved with a kukui tree leaf-and-nut pattern, and the architects had extended the millwork pattern down the walls. Although the walls had been plain white for so many years, they were painted gold during the remodel. When the painting was done, it seemed to Allen almost as if that were the way the millwork was always intended to be. There is actually no gold paint in the temple; it is all 22 and 23 karat gold leaf from Italy, and it was used to bring out the beauty and architectural details. Allen estimated that there are about fourteen miles of gold detailing in the temple.[35]

Several paint patterns are local. In addition to the stained glass and carpets, a kukui nut pattern is also painted into the celestial room ceiling. The hibiscus motif is used in the bride’s room, symbolic of a woman putting a hibiscus flower behind her left ear to indicate she is married. Some of the most intricate patterns are in the garden room, where there is an effect of having koa wood flowers inlaid into the crown molding by highlighting the brims of each flower with gold leaf.[36]

Allen further noted that the murals were also restored and lovingly framed. He then concluded, “It’s been a great privilege to think about what this Temple must have meant when it originally opened. . . . It is a landmark and a monument to all.”[37]

Other changes

Although the temple was closed, President and Sister Workman spent much of their time in Hawaiʻi regularly consulting with the Temple Department about matters of design. For example, it was the department’s intent to install theater seating as is standard in most temples. However, President Workman reminded them of the wide variety of shapes and sizes of patrons who attend the Laie Hawaii Temple and suggested upholstered bench seating would be more accommodating, which they agreed to do.[38]

Celestial room in the Laie Hawaii Temple, 2010. © IRI. Used with permission.

Celestial room in the Laie Hawaii Temple, 2010. © IRI. Used with permission.

Yet perhaps the biggest change to the temple experience as a result of the renovation was the temple’s return to a physically progressive portrayal of the endowment ceremony. From 1978 to 2008, each room—creation, garden, and world—was a separate ordinance room where the endowment was largely given via film before patrons proceeded to the veil. President Workman recalled speaking with the Temple Department about returning to a progressive room-to-room endowment and lauded them for their willingness to do so. Senior architect David Brenchley noted, “We were given the directions that the Church wanted to go back to historically how patrons used all four ordinance rooms and ended up in the Celestial Room.”[39] President Workman concluded, “It made a huge change in the Spirit that was felt in connection with how the endowment was given. . . . The symbolism associated with that movement was made more manifest.”[40]

Today the Laie Hawaii Temple is one of only a few temples that were originally built with, and currently employ, a room-to-room progressive portrayal of the endowment ceremony, with use of the most recent films within each room. Some feel this combination preserves the best of the old while incorporating the best of the new.

Reopening the Temple

A couple weeks before the temple open house, President Workman spoke at the BYU–Hawaii devotional on 5 October 2010 and asked, “Did you feel the absence of Sacred Space in this Island?” He then queried: “In a few short weeks, this beautiful gem of the Pacific will again become Sacred Space. . . . The lives of the living and the dead will be sanctified again. . . . Will your life be one of those sanctified?”[41] Then for three weeks in October and November 2010, the doors of the temple opened to the general public for an open house, where nearly forty-three thousand visitors had the opportunity to walk through the sacred structure. A member of another faith who toured the temple expressed gratitude for the opportunity and said, “I learned a lot and gained an appreciation of your Church that I hadn’t understood before.”[42] A longtime member said: “It’s just beautiful to see the colored glass they’ve added, the wood textures, the carpeting. There’s more natural light coming into the Temple: It’s absolutely beautiful. There’s a flow to everything in there, and more pictures depicting Christ and His ministry on earth.”[43]

Remarkably, among those who attended the open house was “Aunty” Abigail K. Kailimai, then ninety-five, who as a child was present at the 1919 dedication and who attended the 1978 rededication as well. She recalled the excitement she felt as a child riding the boat from the Big Island to Oʻahu and the train to Lāʻie for the dedication, noting, “We were all dressed up to go and mom made a new white dress.” In the years that followed, Sister Kailimai recalled yearly temple trips from the Big Island and staying at the Lanihuli house while in Lāʻie. Of her tour of the temple in 2010 she said, “Today when I was in the Sealing Room, I just couldn’t help thinking when my children were being sealed to me and my husband. I think that was the happiest day of my life.”[44]

Cultural celebration

Abigail K. Kailimai attended the children’s dedicatory session in 1919, the 1978 rededication, and in her nineties the 2010 rededication of the Laie Hawaii

Abigail K. Kailimai attended the children’s dedicatory session in 1919, the 1978 rededication, and in her nineties the 2010 rededication of the Laie Hawaii

Temple. Courtesy of Mike Foley.

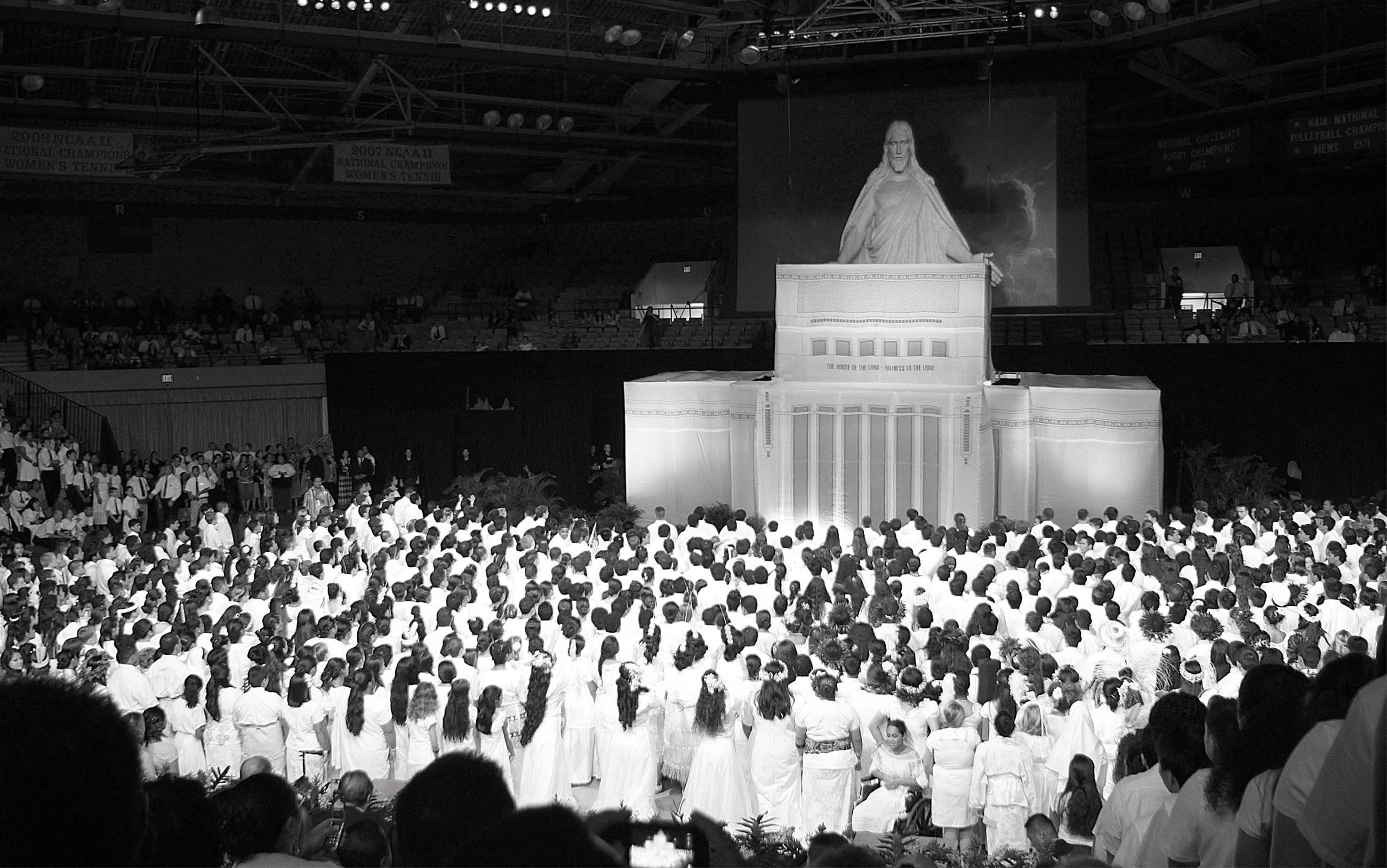

To help inspire them to make the temple more a part of their lives and to strengthen their testimonies, the youth were invited to participate in a cultural event celebrating the history of the Church in Hawaiʻi and the Laie Hawaii Temple. Presented at the Cannon Activities Center on the BYU–Hawaii campus on 20 November 2010, the event was titled “The Gathering Place.” About two thousand youth from several stakes within the temple district performed a ten-scene progressive reenactment of key events in the coming forth of the Church in Hawaiʻi, including the construction of the temple. The final scene culminated with all the youth flowing in from the aisles and doorways to fill the stage while facing a replica of the temple slowly rising in the background with a picture of the Savior depicted on the large screen above. After the song ended, all the youth turned to face the attending prophet, President Thomas S. Monson, and sang “I Love to See the Temple” and “The Army of Helaman.”[45]

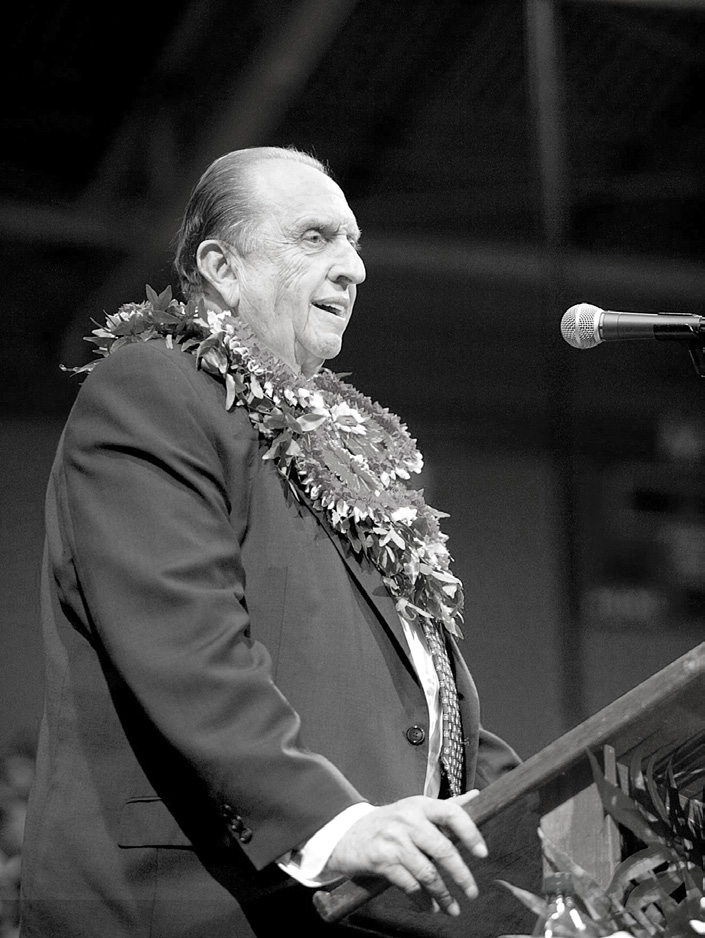

In his remarks to the entire cast before the second performance, President Monson told the youth: “You’re a marvelous sight. . . . Years from now you’ll be telling your children and grandchildren of the opportunity you had to participate in such a tremendous cultural celebration. Stay close to the Church. Keep the commandments. Serve where you’re called to serve.” President Monson further told the youth that the Laie Hawaii Temple, which would be rededicated the next morning, “shines as a beacon of righteousness to all who behold its light.”[46]

Rededication

As part of a cultural celebration for the temple’s rededication, youth reenacted the coming forth of the Church in Hawaiʻi. Photo of culminating scene courtesy of Mike Foley. In his remarks President Thomas S. Monson told the youth that the Laie Hawaii Temple “shines as a beacon of righteousness to all who behold its light.” Photo courtesy of Monique Saenz.

As part of a cultural celebration for the temple’s rededication, youth reenacted the coming forth of the Church in Hawaiʻi. Photo of culminating scene courtesy of Mike Foley. In his remarks President Thomas S. Monson told the youth that the Laie Hawaii Temple “shines as a beacon of righteousness to all who behold its light.” Photo courtesy of Monique Saenz.

President Monson and his wife Frances had visited the Laie Hawaii Temple for their first time in February 1965. Now, forty-five years later, he, again with Frances at his side, had returned as the prophet and President of the Church to rededicate it. On 21 November 2010, three dedicatory sessions originating from the temple’s celestial room were held. President Monson was accompanied by Henry B. Eyring, First Counselor in the First Presidency, and by Apostle Quentin L. Cook. In his remarks, Elder Cook said, “The sacrifices that were made to build these [early] Temples are among our greatest historical heritages.”[47] President Monson powerfully taught:

Temples are built not only of stone and of wood and of mortar, Temples are built of service and sacrifice. Temples are built of fasting and faith. Temples are built of trials, tears, and testimonies. . . .

As we come to this Holy House, as we remember the covenants we make here, we’ll bear [our] trials and overcome temptations. Here we find purpose. Here we discover peace: Not the peace provided by men, but the peace promised by the Son of God.

May our Heavenly Father bless us that we may have the Spirit of Temple worship, that we may be obedient to His commandments, that we may follow carefully the steps of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.[48]

In his prayer to rededicate the temple, President Monson expressed “gratitude for the insight and inspiration of President [Joseph F.] Smith, as well as for others who served faithfully and worked tirelessly so that a House of the Lord could be built here.” Regarding the work in temples for those who have gone beyond, President Monson quoted President Joseph F. Smith, who once stated, “Through our efforts in their behalf, their chains of bondage will fall from them, and the darkness surrounding them will clear away, that light may shine upon them, and they shall hear in the spirit world of the work that has been done for them by their children here, and will rejoice.”

Then, fulfilling his primary purpose, President Monson implored: “Acting in the authority of the everlasting priesthood and in the sacred name of our Redeemer, Jesus Christ, we rededicate unto Thee and unto Thy Son this, the Laie Hawaii Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. We rededicate it as a house of baptism, a house of endowment, a house of sealing, a house of righteousness—for the living and for the dead.” In conclusion he stated: “Father, as we rededicate this sacred edifice, we rededicate our very lives to Thee and to Thy work. May we leave Thy house this day with a renewal of faith and with an added spirit of dedication to Thy work and that of Thy Son.”[49] Nearly two years after the temple had closed for renovation, it was again open for use.

BYU–Hawaii Students as Temple Workers

Many members throughout the Laie Hawaii Temple district form the company of temple workers that keeps the temple operational, and for decades a notable component within it has been BYU–Hawaii students and employees. Early in the Patrick K. Kanekoa presidency (2012–15) changes were made that enabled even more students to serve as temple workers.

When BYU–Hawaii president Steven C. Wheelwright asked President Kanekoa if many students attended the temple, the latter confirmed that was so but added that more students could serve as ordinance workers (normally a six-hour shift). President Wheelwright expressed concern that school demands, combined with work and family obligations, made such a time commitment untenable for most students. As they continued to discuss the matter, President Kanekoa asked, “What if we have the students serve for three hours?”[50] Thus a half shift was created to further extend the opportunity for BYU–Hawaii students to serve as temple ordinance workers. Echoing the sentiment of previous temple administrations, President Kanekoa affirmed the value of these students to the work in the Laie Hawaii Temple and added, “They’re amazing, . . . they’re bright, they’re smart, they know. They have a great spirit about them.”[51]

Of course, this benefit goes both ways. BYU–Hawaii president Eric B. Shumway had expressed his concern that students may “fill their lives and their calendars with study and entertainment, but neglect this opportunity to encounter Heavenly Father in a special way in his house.” He said further, “By the same token, one of my greatest joys is to meet students in the temple, sometimes as temple workers, sometimes sitting quietly with bowed head in the celestial room. I bear solemn testimony that you are in the presence of God there.”[52] Later school president John S. Tanner echoed, “I’m convinced that you, young people especially, will become the leaders you need to become. Not just from the lessons you learn here but lessons you will learn in the Temple.”[53]

Unprecedented Youth Participation

It seems safe to say that the decade of 2010–19 has seen a seismic shift Churchwide in the manner and amount of youth participation in temple work. For previous generations of youth, temple work was mainly a prescheduled event arranged by Church leaders and conducted as a group. Further, genealogy work was generally considered something done by older generations.

However, speaking directly to the youth in his October 2011 general conference address, Elder David A. Bednar said: “I know of no age limit described in the scriptures or guidelines announced by Church leaders restricting this important service [family history] to mature adults. . . . It is no coincidence that FamilySearch and other tools have come forth at a time when young people are so familiar with a wide range of information and communication technologies.” He then added, “I invite the young people of the Church to learn about and experience the Spirit of Elijah. I encourage you to study, to search out your ancestors, and to prepare yourselves to perform proxy baptisms in the house of the Lord for your kindred dead (see Doctrine and Covenants 124:28–36).”[54]

Not long after Elder Bednar’s challenge, President Kanekoa, while attending a temple presidents’ training seminar in Salt Lake City, heard of walk-in baptisms (without appointment) and right away made arrangements to do so in the Hawaii Temple. “And, boy, it just boomed,” recalled President Kanekoa.[55] Once this new policy was instituted in Lāʻie in 2012, youth could be seen lining up outside the temple baptistry early in the morning and at other times.

Also during the Kanekoa presidency, it was announced that those who received a mission call could serve as temple workers while making final preparations for their mission. Of this development, temple matron Elizabeth Kanekoa noted, “What more perfect place can you be [before serving a mission]?” She then observed that “after their mission, they would come back and be temple ordinance workers.”[56]

Then the First Presidency announced that, starting in 2018, “young women may be asked to assist with tasks in the temple baptistry currently performed by adult sisters serving as temple ordinance workers or volunteers,” and “ordained priests may be asked to officiate in baptisms for the dead, including performing baptisms and serving as witnesses.”[57] When the Laie Hawaii Temple opened in January 2018, the first youth group to enter the baptistry was from the Kahuku First Ward. Young men Seth Reid and Joseph Toelafua baptized, and Camrin Waka witnessed the baptisms.[58] Using their priesthood authority to baptize and witness was an opportunity few young men had previously experienced before missionary service, but now many do so regularly in the temples, as part of the work to bring salvation to those in the spirit world.

An Incredible Missionary Tool

Over the past century, likely more people have been introduced to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and the purpose of temples on the Laie Hawaii Temple grounds than at any other Church site except Temple Square in Salt Lake City. Tour groups and other visitors circling the island have been visiting the temple grounds since before the temple was dedicated in 1919, and for more than fifty years the Polynesian Cultural Center has been shuttling visitors to the temple grounds with its tram tour of Lāʻie as well. In 2017 alone there were a quarter of a million visitors, a large majority of whom were not members of the Church.

Jeff and Heidi Swinton, directors of the Laie Hawaii Temple Visitors’ Center from 2016 to 2017, said: “This Visitors’ Center is the mouthpiece. The temple can’t speak. People can’t even go into the temple. . . . They go home with pictures of the temple, pictures of the Christus, pictures of themselves with sister [missionaries], and they will go home and see someone walking in their neighborhood wherever they are in the world with a [missionary] badge on, and they will remember what they felt when they were walking on the grounds of the Visitors’ Center. This is the Lord inviting people to come to Christ.”[59]

Over the past century, likely more people have been introduced to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and the purpose of temples while visiting the Laie Hawaii Temple grounds than at any other Church site except Temple Square in Salt Lake City. Through the years young sister missionaries have increasingly become the welcoming face to those who visit the temple grounds. Courtesy of Stephen B. Allen and Mike Foley.

Over the past century, likely more people have been introduced to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and the purpose of temples while visiting the Laie Hawaii Temple grounds than at any other Church site except Temple Square in Salt Lake City. Through the years young sister missionaries have increasingly become the welcoming face to those who visit the temple grounds. Courtesy of Stephen B. Allen and Mike Foley.

Over the years, young sister missionaries have increasingly become the welcoming face of the visitors’ center. Now nearing forty in number serving at a time, these sister missionaries are capable of speaking numerous languages—Mandarin, Cantonese, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, Tagalog, English, and more. Furthermore, with the advent of technology, if a visitor asks for more information, the sisters can send their contact information instantly via text message to missionaries in the person’s hometown. When not greeting visitors, the sisters put on headsets in a small call center at the back of the visitors’ center, where they communicate with people they’ve met on the temple grounds, answer or send referrals, or respond to questions submitted by people online at ComeuntoChrist.org or other Church websites. “There have been times when I have walked in and found two sisters kneeling on the floor, praying with people on the phone. It’s as if they were teaching them face-to-face,” Elder Swinton said. “They are teaching all the time. It’s a busy place.” Although the sisters may occasionally receive news that someone has been baptized as a direct result of their efforts, they see their role as primarily finding and sending referrals.[60]

The Laie Hawaii Temple Visitors’ Center continues to be an incredible missionary tool. The idea to include a visitors’ bureau within the temple’s original design was discerning. With such a strong and consistent missionary component on its grounds, it is easy to view the Laie Hawaii Temple as offering salvation to all of God’s children—introducing people to the restored gospel, allowing members to make further covenants, and offering covenants to those who have passed on.

Continued Reach of the Laie Hawaii Temple

Though its geographic boundaries are now relatively small, the Laie Hawaii Temple continues to have a far-reaching effect. Former temple president H. Ross Workman stated it this way:

The boundaries of the temple are shrinking. That’s true for every temple district because they keep building new temples. And I think that’s awesome. But the reach of the [Laie Hawaii] temple doesn’t change because people migrate to Hawaii for lots of reasons: education, economics, vacation, whatever it is, so that temple still has reach that goes way beyond its boundaries. . . .

Hawaii is a very tolerant place for cultures. They have a big Filipino population, big Asian population, huge Samoan population, huge Tongan population. And they bring family when they come.

This little temple that Joseph F. Smith saw in 1915 and Heber J. Grant dedicated in 1919, this little temple has a huge effect. And hundreds of times, I felt the witness of the Spirit on the value of that sacred work in that little temple for the Church worldwide. I still feel it to this very day.

Only four Latter-day Saint temples (St. George, Logan, Manti, and Salt Lake) reached one hundred years of operation before the Laie Hawaii Temple. And as was true for the pioneer temples preceding it, the Laie Hawaii Temple was literally built by local members who consecrated their skill, time, and means to its construction. They hauled the lava stones, they set the forms, they poured the concrete, they prepared the meals, they mended the clothes, and they raised and donated the money, paid a generous tithe, and worked the plantation to pay for it. Yet the Laie Hawaii Temple is a pioneer in its own right: It was the first temple dedicated in an effort to bring temples to people beyond the main body of the Church in Utah, and it was the first temple to reach and accommodate significant numbers of diverse cultures and languages.

The Laie Hawaii Temple was built at a time of local prosperity, yet it languished for some time in poverty. It was initially built on the faith of Polynesian members, yet it has served many other cultures and languages. The temple directly experienced the fear and uncertainty of world war, yet it has also enjoyed rich freedom. It stood alone for decades as the nearest temple to a majority of the world’s population, and as a sign of Churchwide progress it now covers only a small fraction of what it once did. And though the work within the temple stands singular, it has uniquely linked with other institutions in furthering the Lord’s kingdom. The story of the Laie Hawaii Temple is truly remarkable.

Come and Partake

Laie Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Gary Davis.

Laie Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Gary Davis.

The ultimate purpose and power of the Laie Hawaii Temple is not found in its history, its outward beauty, or on its grounds, but rather can be discovered only by those who worthily spend time within its walls.

It has been said that in temples “the story of life is simplified for the understanding of men.”[61] Arguably nowhere is the plan of salvation—God’s design to help us grow, learn, and experience joy—taught in a more chronologically comprehensive manner than in the temple. In the temple, the plan is nearly complete in its linear portrayal of who we are, the purpose of this life, our endless nature, the centrality of family, and our eternal potential.

What’s more, all this is taught interactively, progressively, repetitively, kinesthetically, symbolically, and in an environment of peace and contemplation free of distraction, comparison, and materialism.

Sincerity in temple worship demands individual introspection, an assessment of where we stand, and consideration of who we can become, and ultimately all is consummated through commitments that deeply connect us with the Divine.

Of our personal experience within the temple, three-time Laie Hawaii Temple president Edward L. Clissold concluded:

There is no magic at the door of the temple that turns a sinner into a saint. The place for us to prepare to meet the Lord in this holy house is in the quiet walks of our everyday life, in our homes, in our business, as we associate with [others], in our private lives. Then we shall come to the temple, not as a pilgrimage, not as an act of penance, not to be forgiven for sin, but we shall come here to partake of the rewards which God has for the faithful. Here we shall receive the glorious endowments of the priesthood. Here we shall be sanctified. Here we shall do work for our dead kindred. Here we shall be saviors on Mt. Zion. Here we shall receive the strength and the fortitude that will carry us through life.[62]

Notes

[1] Barbara Clarke, reminiscence, MS 31094, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT. Some names in the quotation were altered for clarity. Sister Clarke further explained: “For many of our ordinance workers, English was a second language. This was hard for them. Many had just learned to speak pigeon [pidgin] English, using a lot of dis and dat and leaving out introductory words such as ‘the’—etc. This was a challenge, but they were so eager to serve, and so humble.”

[2] See Glenn Lung and Julina Lung, interview by Gary Davis, 21 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[3] Lung, interview.

[4] See Wayne Yoshimura, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 16 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[5] “Hale Laʻa, BYUH, Temple Projects Dedicated,” Kaleo o Koʻolauloa, 16 December 2004, 1–2.

[6] Taralyn Trost, “President Hinckley Joins in Island Celebrations, Groundbreaking,” Ensign, January 2004, 74.

[7] See “Hale Laʻa, BYUH, Temple Projects Dedicated,” 1–2.

[8] “Hale Laʻa, BYUH, Temple Projects Dedicated,” 1–2.

[9] “President Hinckley Presides over Hale Laʻa Blvd. Groundbreaking, Blessing,” BYU–Hawaii Alumni Association e-newsletter, October 2003. https://

[10] “Hale Laʻa, BYUH, Temple Projects Dedicated,” 1–2.

[11] See “Hale Laʻa, BYUH, Temple Projects Dedicated,” 1–2.

[12] See “Laie Temple Windows Restored, Grounds Relandscaped,” Kaleo o Koʻolauloa, 6 October 2005, 9.

[13] See “Laie Temple Windows Restored, Grounds Relandscaped,” 9.

[14] Wayne O. and N. Bernice Ursenbach, interview by Clinton D. Christensen and John Mills, 27 September 2016, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[15] See Ursenbach, interview.

[16] See H. Ross and Kaye Workman, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 21 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[17] The Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 17.

[18] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 16.

[19] See Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 17.

[20] See Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 18–19.

[21] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 20.

[22] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 29.

[23] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 18–19.

[24] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 23–24.

[25] Scripture mentions that the oxen were placed in groups of three, with each group facing outward toward a point of the compass and with the large basin placed on their backs. See 1 Kings 7:25; and 2 Chronicles 4:4. See also Edward J. Brandt, “Why Are Oxen Used in the Design of Our Temples’ Baptismal Fonts?,” Ensign, March 1993, 54–55.

[26] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 23–24.

[27] See Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 30–31.

[28] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 30–31.

[29] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 30–31. Page 43 further explains: “The kukui nut tree is repeated several times in the Laie Hawaii Temple. The kukui nut tree is known as a tree of light in native Hawaii. Because of the high oil content of the kukui nut, ancient Hawaiians would burn the nuts to provide light. Hawaiians also extracted the oil from the nut and burned it in a stone oil lamp called a kukui hele po (light, darkness goes) with a wick made of kapa cloth, similar to the more well known variety of tapa cloth. The kukui nut, also known as the candlenut, burns in approximately 15 minutes which led to the ancient Hawaiian measure of time.”

[30] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 30–31. Holdman further explains: “In the Celestial Room door windows there are also pieces cut from white agate stone. When the Lord came down to the Americas and was quoting Isaiah, he spoke of the last days and the building of Temples. He said, ‘And I will make thy windows of agates . . . and all thy children will be taught of the Lord; and great shall be the peace of thy children.’ (3 Nephi 22:12–13).”

[31] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 30–31.

[32] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 32–33.

[33] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 32–33.

[34] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 34–35.

[35] See Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 34–35.

[36] See Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 34–35.

[37] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 34–35.

[38] See Workman, interview.

[39] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 29.

[40] Workman, interview.

[41] H. Ross Workman, “Sacred Space,” BYU–Hawaii devotional, 5 October 2010.

[42] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 116.

[43] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 43.

[44] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 118.

[45] See Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 122–54.

[46] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 128.

[47] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 163.

[48] Laie Hawaii Temple: 2010 Rededication, 164.

[49] Thomas S. Monson, “Dedicatory Prayer, Laie Hawaii Temple, 21 November 2010,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://

[50] Patrick and Elizabeth Kanekoa, interview by Michael Morgan, 18 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[51] Kanekoa, interview.

[52] Eric B. Shumway, “Revelation and the Temple of God,” BYU–Hawaii Devotional, 4 May 2006.

[53] John S. Tanner, “Thoughts on Thanksgiving and Christmas,” BYU–Hawaii Devotional, 29 November 2016.

[54] David A. Bednar, “The Hearts of the Children Shall Turn,” Ensign, November 2011.

[55] Kanekoa, interview.

[56] Kanekoa, interview.

[57] Camille West, “Church Adds New Opportunities for Youth and Children to Prepare for and Participate in Temples,” Church News, 17 December 2017. See First Presidency letter, 14 December 2017, https://

[58] Reminiscences courtesy of Mark James.

[59] Brooklyn Redd and Patrick Campbell, “Swintons’ Impact on the Visitors’ Center,” Ke Alakaʻi, 19 January 2018, 16–22.

[60] Trent Toone, “Laie Temple Visitors’ Center Experiences Increase of More than 100 Visitors per Day,” Church News, 19 May 2016.

[61] Stephen L Richards, “Contributions of Joseph Smith,” Millennial Star, 27 May 1937, 325.

[62] Edward L. Clissold, at the dedication of the New Zealand Temple in 1958, in Edward L. Clissold papers, in private possession.