A Time of Delay and Preparation

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "A Time of Delay and Preparation," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 129–140.

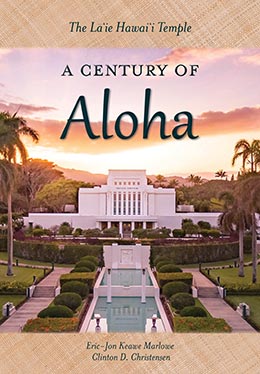

Completion of the Hawaii Temple occurred in the final throes of World War I, the rise of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the ailing health and eventual passing of President Joseph F. Smith, Lāʻie Chapel, with President Samuel E. Woolley at pulpit. Courtesy of Church History Library. Flu and War images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Completion of the Hawaii Temple occurred in the final throes of World War I, the rise of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the ailing health and eventual passing of President Joseph F. Smith, Lāʻie Chapel, with President Samuel E. Woolley at pulpit. Courtesy of Church History Library. Flu and War images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

President Joseph F. Smith had taken a very personal interest in the Hawaii Temple’s construction, visiting the site in 1916 and 1917 to monitor its progress.[1] Then, with the completion of the temple in 1918, anticipation was mounting that the prophet would soon arrive for the temple’s dedication. Although by this time President Smith had been ailing for months, leaving him unable to travel to Lāʻie to dedicate the new temple, hope remained that his health would improve, so the dedication was deferred.[2]

A Reassuring Revelation amid Profound Loss

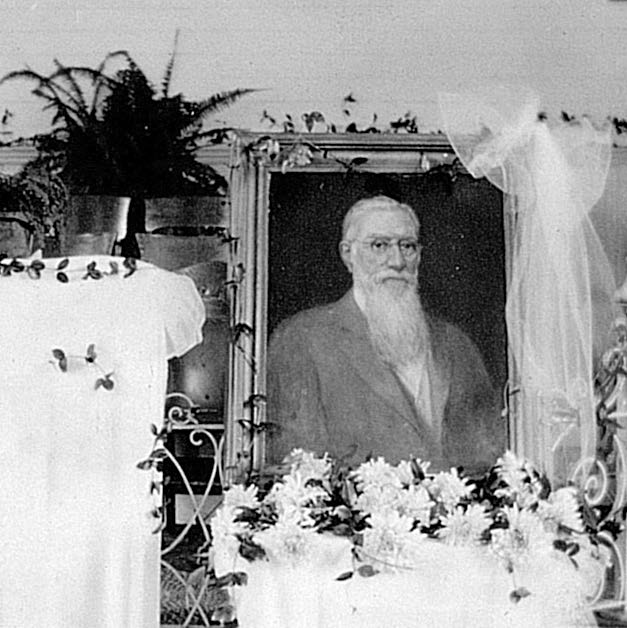

The temple’s completion coincided with the final stages of World War I and the rise of the 1918 flu pandemic, an astonishingly devastating period. The war that would claim nine million lives was not yet over, nor had the developing epidemic that would claim at least fifty million lives yet reached its full pandemic strength.[3] Amid these calamitous world events, his multiplied sorrow at the recent passing of family members,[4] and his continued decline in health, President Smith received on 3 October 1918 a remarkable vision of the Savior’s visit to the spirit world (recorded in Doctrine and Covenants 138). With timely relevance, the vision “made known” the vast scope of the work of redemption and how it is accomplished beyond the veil (see 138:36–37). In revealing this merciful provision in the postmortal spirit world, the vision “reconfirm[ed] the connection of temple work to the redemption of the dead” and “invites us, the living, to actively participate, through seeking after the dead by performing vicarious ordinances . . . and in so doing drawing the two worlds together.”[5] Given during a time of profound loss of human life, President Smith’s vision was a striking reminder of the need for more temples that provide the vital ordinances necessary to complete the work being done in the spirit world.

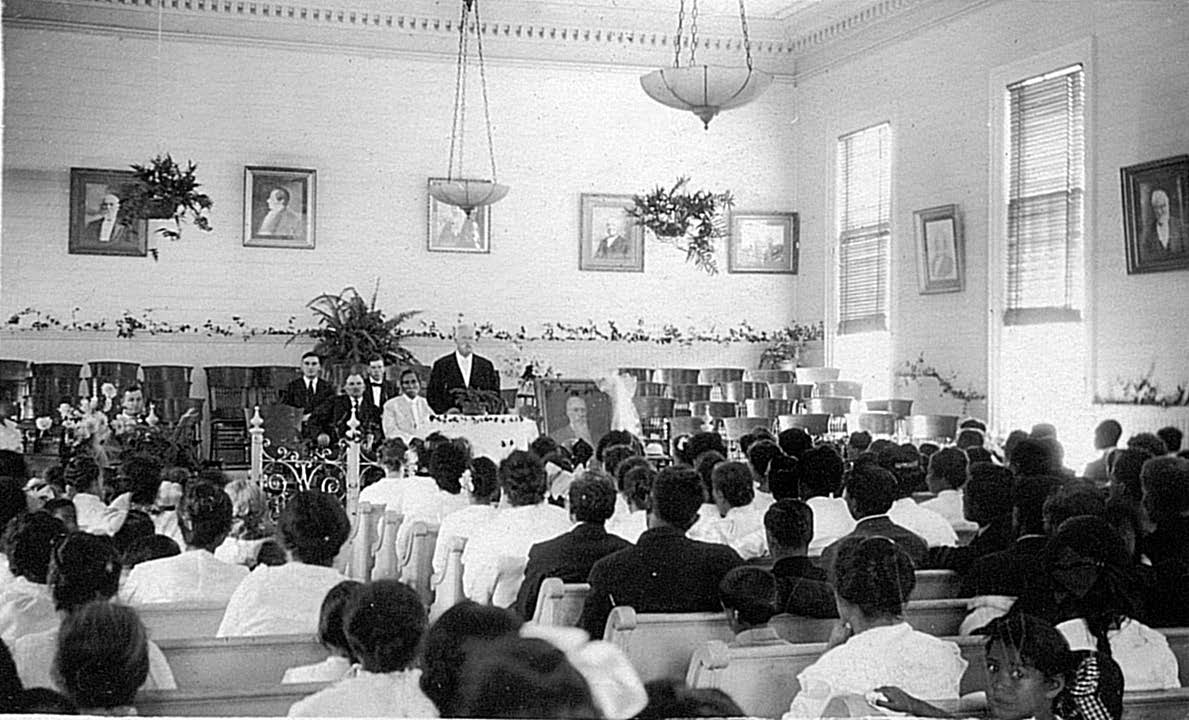

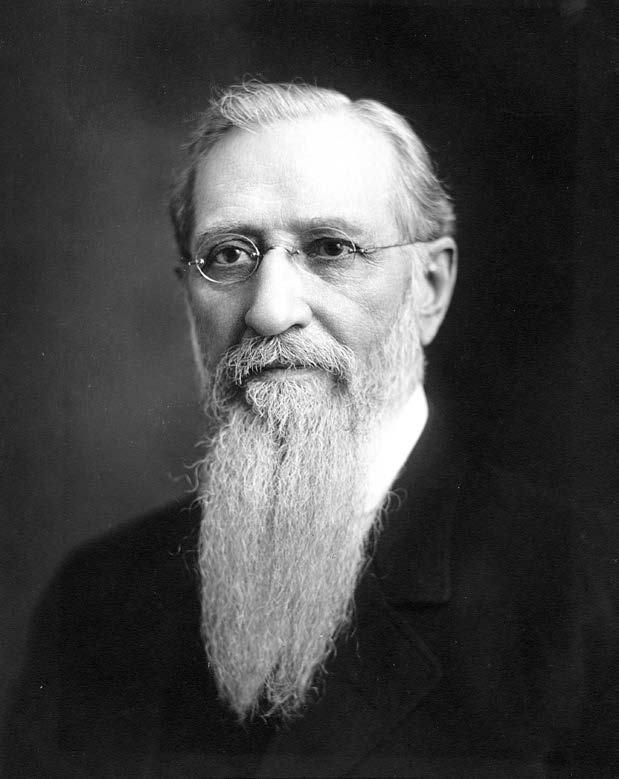

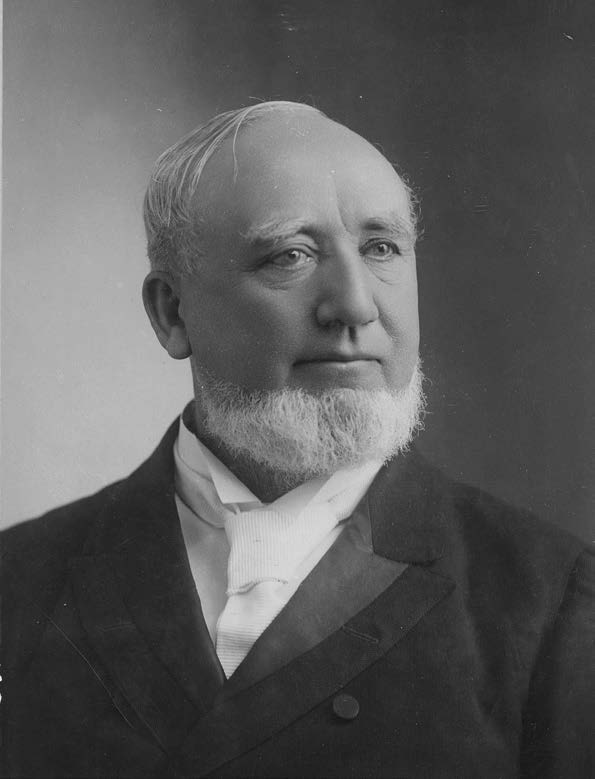

The combined missions and ministries of George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith were markedly instrumental in the early construction of a temple in Hawaiʻi. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The combined missions and ministries of George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith were markedly instrumental in the early construction of a temple in Hawaiʻi. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Regrettably, President Smith did not recover sufficiently from his illness to return to Hawaiʻi and dedicate the temple. He passed away on 19 November 1918, eight days after the official end of World War I and six days after his eightieth birthday. News of his passing sent a gloom over the Church in Hawaiʻi. In memorial services in the Lāʻie Chapel, “remarks were made in regard to the life’s labors and integrity of the beloved leader.” In a very keen way, “the Hawaiians felt that they had lost their best friend, as Pres. Smith was always ready and willing to assist them.”[6]

Today in the Hawaii Temple, in the hallway behind the recommend desk, are two portraits: one of Joseph F. Smith, the other of George Q. Cannon. Cannon, eleven years Joseph F. Smith’s senior, played a leading role in establishing the restored gospel in Hawaiʻi. His authentic regard for the Hawaiian people and zeal for the work set the tone for generations of missionaries that followed. Joseph F. Smith, at age fifteen, arrived in Hawaiʻi just two months after Cannon departed and over the course of three missions would serve nearly seven years among the Hawaiian people. “Pūkuniahi” and “Iosepa” (affectionate Hawaiian names for Cannon and Smith) never forgot Hawaiʻi, and in a tangible way their ministries represent the founding of the work in Hawaiʻi and the realization of the fulness of that work with a temple.

A Time of Delay and Preparation

No public funeral was held for President Smith because Utah was under quarantine owing to the influenza epidemic. In a meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve on 23 November 1918, Heber J. Grant was ordained and set apart as the seventh President of the Church. President Grant planned to dedicate the Laie Hawaii Temple shortly after the April 1919 general conference, but another surge of the flu epidemic caused the April conference to be postponed until June.[7] It was then resolved to dedicate the temple shortly after the October conference,[8] but other pressing Church matters postponed the temple’s dedication until the latter part of November 1919—nearly seventeen months after its completion.[9]

The temple’s first president

William Waddoups was born in 1878 and raised on a modest farm in Bountiful, Utah. In January 1900 he was called to serve a mission to Colorado, but Joseph F. Smith, then Second Counselor in the First Presidency, changed William’s call to Hawaiʻi.[10] His older brother Anson was serving in Hawaiʻi at the time and, without notice of the change, was shocked when William appeared at the Honolulu district mission home.[11] William served with Anson for six months and deemed the opportunity “a great blessing.”[12] During his missionary service from 1900 to 1904, William developed a deep love for the Hawaiian people and became fluent in the Hawaiian language.

Olivia Sessions Waddoups and William Mark Waddoups. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Olivia Sessions Waddoups and William Mark Waddoups. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Olivia Sessions Waddoups was born in 1883 and was also raised in Bountiful, Utah. William and Olivia became acquainted through a Sunday School class, and they corresponded while William served his mission in Hawaiʻi. At age eighteen, Olivia became a worker in the Salt Lake Temple, a rare privilege for someone so young. She was “closely associated” with and mentored by Bathsheba W. Smith, matron of the Salt Lake Temple and Relief Society General President.[13] Unlike the usual custom at that time of a sister receiving her temple blessings when she married or went on a mission, Olivia received her endowment without serving a formal mission and a year before marrying William.

Upon William’s return from Hawaiʻi in 1904, they were married in the Salt Lake Temple and then spent the 1904/

At the closing of Iosepa, William Waddoups “was called to work in the Salt Lake Temple in preparation for [a] mission to the Temple in Hawaii.”[16] He did so from September 1917 to June 1918, when, with the temple basically complete, President Smith called Waddoups to serve as president of the Hawaii Temple.[17] The Waddoups family, with their four children ranging in age from six to fourteen, arrived in Hawaiʻi in July 1918.[18] Called at age forty, William Waddoups was twenty-two years younger than any other temple president serving at that time. He would serve as president of the Hawaii Temple for almost sixteen years.[19]

Preparing members for temple service

Anticipating that the temple would soon be dedicated, President Waddoups described the months of waiting as “uncertain and anxious . . . as we had not regular duties to perform much of the time.” He worked several jobs, such as weighing and loading pineapples and managing the plantation stores at Lāʻie and Hauʻula.[20] Yet as the delay continued, he found purpose traveling among the Saints, teaching congregations and individual members about the importance of temple work and instructing them in gathering their genealogy.

After President Waddoups had done so throughout the island of Oʻahu, mission president Samuel Woolley called him to go to the “Big Island” of Hawaiʻi and do the same.[21] Then under President E. Wesley Smith, who replaced Samuel Woolley as mission president in July 1919, President Waddoups traveled and taught among the Saints on the islands of Maui, Molokaʻi, and Kauaʻi as well.[22] By the time he returned from Kauaʻi, the last stop of his five-island temple preparation tour, it was early November 1919—and it was then that word arrived from President Grant that the dedication would take place later that month.

Temple Open House

During the delay, tours of the temple were freely provided to persons who were not members of the Church, a novel practice at that time. President Waddoups recorded:

I have had the pleasure of showing I think at least 500 people not of our faith through the temple. They have one and all been profuse in their praise of its beauty. All have been deeply impressed with the spirit of peace and the sacred quiet of the Temple. We have explained many of the beautiful principles of our Gospel to each company and the hearts of many have been reached. Many have marveled at the beauty of our religion and the perfection of our organization. We feel that much good has been accomplished and that many friends have been made. Most of the leading men and women, prominent ministers, business men, Judges, doctors, lawyer and politicians, of Honolulu and this Island have been through the Temple. We feel that we have many friends here and are assured that the time is ripe for the work to be opened.[23]

Mission presidents Samuel E. Woolley and E. Wesley Smith also took guests through the temple, and President Grant and his party accompanied a group of nonmember visitors as they toured the inside and outside of the temple in the days just before the dedication. All together it was estimated that one thousand nonmembers attended the temple open house.[24] Such use of a Latter-day Saint temple as a means of public outreach and missionary work was unprecedented, and it provided a pattern that would become common practice among temples that followed.[25]

New Leadership

As mentioned, Elias Wesley Smith was called as mission president in July 1919, replacing Samuel Woolley, who had served as both mission president and plantation manager for twenty-four years. E. Wesley Smith, then age thirty-three, was the son of Joseph F. Smith. He was born in Lāʻie while his parents resided there from 1885 to 1887, and at age twenty Wesley had served a three-year mission in Hawaiʻi (1907–10).[26]

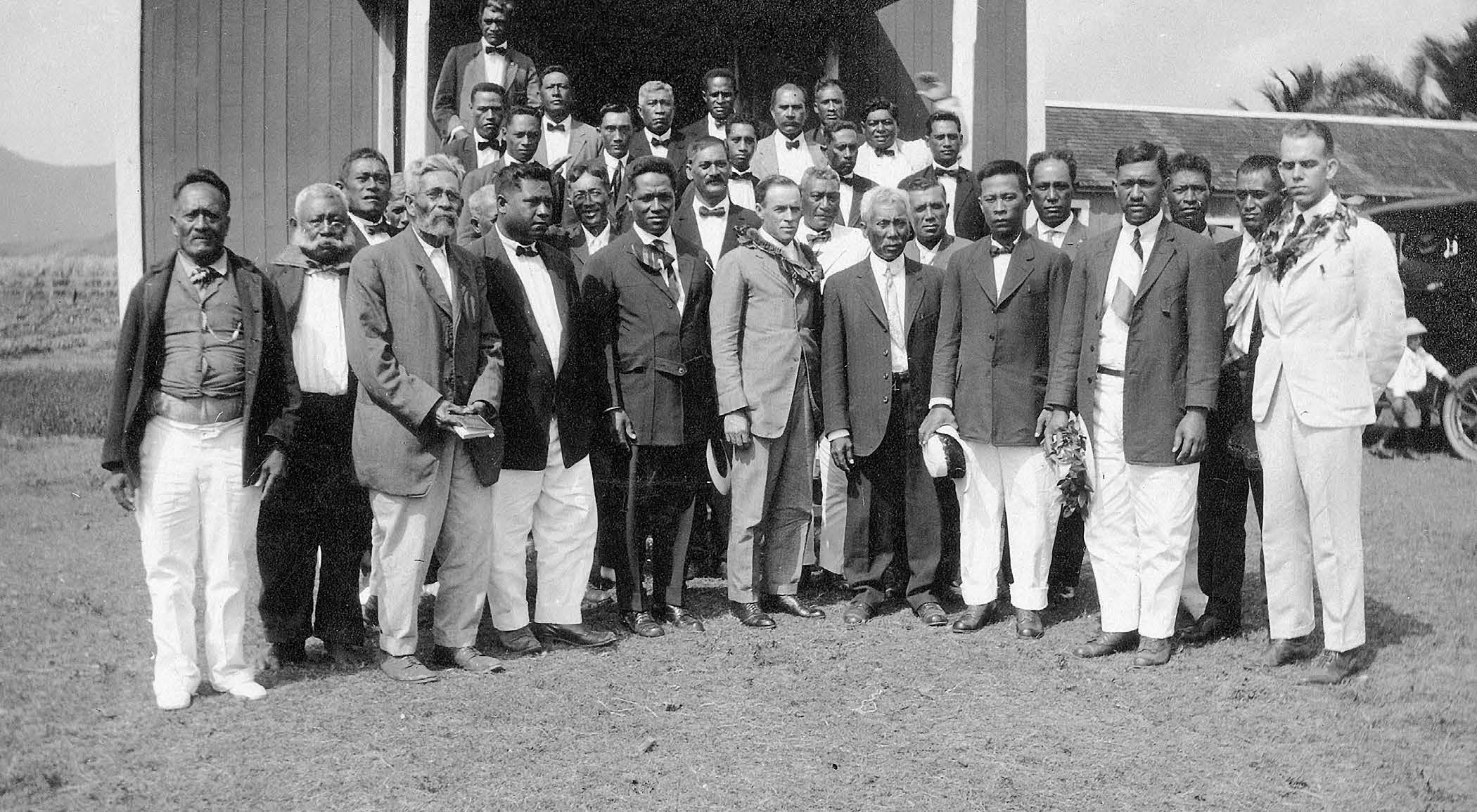

During the delay in the temple’s dedication, President Waddoups found purpose traveling among the Saints, teaching congregations and individual members about the importance of temple work and instructing them in gathering their genealogy. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

During the delay in the temple’s dedication, President Waddoups found purpose traveling among the Saints, teaching congregations and individual members about the importance of temple work and instructing them in gathering their genealogy. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Having considered mission logistics and the changing demographics in Hawaiʻi, shortly after his arrival President Wesley Smith moved the mission headquarters from Lāʻie to Honolulu and emphasized preaching the gospel to all nationalities, instead of primarily among Hawaiians.[27] During his years of service as mission president, he was a strong proponent of the temple.

Especially consequential to the temple’s immediate leadership was the calling of Duncan McNeil McAllister as the Hawaii Temple’s first recorder, a position founded in scripture (Doctrine and Covenants 128:1–5). An Improvement Era article said that McAllister’s “experience in temple work is exceeded by no living person.”[28] Before being called to the Hawaii Temple in 1919, McAllister served as temple recorder in the Salt Lake and St. George Utah Temples for twenty-six years (1893–1919).[29] The value of such experience is underscored by the fact that in 1919 there was no temple department in the Church or correlated materials to guide and direct leaders in the affairs of temple administration. In effect, McAllister filled that role. President Waddoups considered him a “man of much experience” and “a great help and an inspiration to me in my new work.”[30] What’s more, McAllister’s daughter Katie, who had served a mission in Hawaiʻi from 1912 to 1914, was called to serve with her father in the temple with responsibility over temple clothing.[31]

Although the lengthy delay between the completed temple and its dedication was unanticipated, it provided more time to better prepare members for temple work and worship. Also, the opportunistic use of the undedicated temple as a missionary tool set a precedent for temples that followed. Even so, leaders and members were elated when they at last received assurance that President Grant and his party would soon arrive to dedicate the temple.

From left to right: Duncan and Catherine McAllister, Katie McAllister, and Olivia and Mark Waddoups. Called as the Hawaii Temple’s first recorder, Duncan M. McAllister was considered perhaps the most knowledgeable person regarding temple work and was a valuable asset to the early work done in the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

From left to right: Duncan and Catherine McAllister, Katie McAllister, and Olivia and Mark Waddoups. Called as the Hawaii Temple’s first recorder, Duncan M. McAllister was considered perhaps the most knowledgeable person regarding temple work and was a valuable asset to the early work done in the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Notes

[1] See Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 316, 320. Richard J. Dowse explained that “he [Joseph F. Smith] was intimately involved in the details of its [the temple’s] construction—even to the point of ordering the correction of the color schemes in a mural’s water scene.” Richard J. Dowse, “Joseph F. Smith and the Hawaiian Temple,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill, Brian D. Reeves, Guy L. Dorius, and J. B. Haws (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013), 279–302. See also Lewis A. Ramsey correspondence, 7 May 1917, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[2] The prophet uncharacteristically mentioned his poor health in the October 1917 and April 1918 general conferences; see Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 320–22.

[3] This number of lives taken by the flu comes from George S. Tate, “I Saw the Hosts of the Dead,” Ensign, December 2009, 57–58, which references Niall P. A. S. Johnson and Juergen Mueller, “Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918–1920 ‘Spanish’ Influenza Pandemic,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, no. 1 (2002): 105–15. Johnson and Mueller caution that “even this vast figure [of 50 million] may be substantially lower than the real toll, perhaps as much as 100 percent understated” (115).

[4] In January 1918 President Smith’s eldest son, Hyrum Mack Smith, an Apostle, died of a ruptured appendix; later that same year Hyrum’s widow, Ida Bowman Smith, also passed away, leaving behind their five children.

[5] Tate, “I Saw the Hosts of the Dead,” 59.

[6] Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 24 November 1918.

[7] See Heber J. Grant to Samuel Woolley, 24 April 1919, Heber J. Grant Collection, MS 1233, Historian’s Office letterpress copybooks, CHL, 54:726.

[8] See Grant to Woolley, 16 June 1919, 54:751.

[9] See Heber J. Grant to E. Wesley Smith, 15 October 1919, Heber J. Grant Collection, 55:124.

[10] See William M. Waddoups, “Personal History of William Mark Waddoups,” William M. Waddoups Papers, 1883–1969, CHL, 3.

[11] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 3. See also Thomas Anson Waddoups, “The Biography of Thomas Anson Waddoups,” CHL. Born 23 December 1875, Anson was two years and two months older than William.

[12] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 3.

[13] Dorothy O. Rea, “Thou Shalt Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself,” Church News, 9 July 1956, 11.

[14] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 5.

[15] Waddoups, “Biography of Thomas Anson Waddoups.”

[16] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 5.

[17] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[18] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 22 July 1918.

[19] Three years’ service for temple presidents would not become standard until the 1980s.

[20] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6; and William M. Waddoups, journal, 8 April–17 July 1919 and 22 November 1919, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[21] See Waddoups, journal, 26 February 1919–8 April 1919.

[22] See Waddoups, journal, 18 July 1919. For a brief summary of Waddoups’s visit to Kalaupapa colony while on the island of Molokaʻi, see “Hawaiian Mission, Kalaupapa Branch,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 11 November 1919, 164.

[23] Waddoups, journal, circa 21 November 1919.

[24] See “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 6 January 1920, 229–32.

[25] The Salt Lake Temple had a small, private open house before its dedication, but it was not for the general public. Holding public open houses before temple dedications is a common practice today.

[26] See “Early Mormon Missionaries: Elias Wesley Smith,” Church History, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://

[27] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 16 September 1919, which states, “The following account of this tour [of the Islands] was published in the ‘Liahona’ of Oct. 28, 1919 [Wilford W. King, Mission Clerk]. ‘Heretofore our labors in this land have been mostly among the Hawaiians. But from now on the Gospel is going to be carried to all the nationalities on the islands.’”

[28] “The House of the Lord in Hawaii,” Improvement Era, March 1921, 460.

[29] See Duncan M. McAllister, “A Testimony,” Improvement Era, December 1918, 152–55.

[30] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[31] See “Early Mormon Missionaries: Katie Perkes McAllister,” Church History, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://