The Temple Site: Private Dedication, Public Announcement

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "The Temple Site: Private Dedication, Public Announcement," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 57–70.

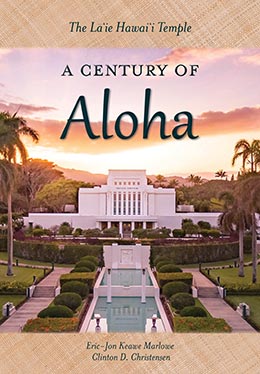

Saints departing the Lāʻie Chapel (named “I Hemolele”) after Sunday services. This chapel would be the site chosen and dedicated for the construction of a temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Saints departing the Lāʻie Chapel (named “I Hemolele”) after Sunday services. This chapel would be the site chosen and dedicated for the construction of a temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Now confident that the time to build a temple in Hawaiʻi had come and would meet with the Lord’s favor, President Joseph F. Smith straightway decided to dedicate a site. He chose to do so on 1 June, the birthday of Brigham Young,[1] under whose prophetic direction missionaries were first sent to Hawaiʻi. President Young later recommended a “gathering place” in the islands and endorsed the location of Lāʻie—the very land, now fifty years later, on which this temple would be built. For President Smith, the date carried a personal connection, for it was President Young who had looked after the orphaned teenager, called him to serve two missions in Hawaiʻi, set him apart as an Apostle at age twenty-eight, and then called him to serve as his counselor for more than ten years. That President Smith deliberately chose to dedicate the temple site on Brigham Young’s birthday was a fitting honor.

A Private Dedication

Just before a community gathering at 8:00 p.m. at the mission home to bid farewell to the prophet and others who would depart the next day, there occurred “an ecclesiastical event of historic significance.”[2] In his brief account of what transpired, President Smith wrote, “This evening Brothers Smoot, Nibley and myself walked over to the meeting house & had some conversation on the subject of recommending that a small temple or endowment house be erected here at Laie. We were agreed and I offered a prayer and dedicated the meeting house site for a temple provided the counsel of the First Presidency & 12 shall approve it.”[3] With added detail, Elder Smoot recorded:

At 5 minutes to eight p.m. President Smith asked Bp Nibley and myself to take a walk. As we were leaving the house we met most of the people of Laie on their way to the Missionary House to hold a meeting and tell us good bye. We proceeded to the meeting house [I Hemolele] located on a little hill about 400 yards southeast of the Mission House arriving there about 8 oclock. We entered the enclosure and stopped just west of the building and President Smith said Bp Nibley had suggested to him that as the Mission was in a financial condition that [if] it could build a small Endowment House or Temple it should do so and also thought that the meeting house should be moved from its present location and the Endowment or Temple be located on the hill now occupied by the Meeting House. Pres. Smith said if that met the approval of all three of us he felt impressed to consecrate and dedicate the ground for that purpose. . . . Being agreeable to us all, President Smith at 8:15 p.m. lead in prayer and the ground was dedicated and consecrated for the purpose named above. A feeling of satisfaction pervaded the hearts of each one of us. . . . This can be considered a blessed day for members of the church living on the islands of the Pacific Ocean.[4]

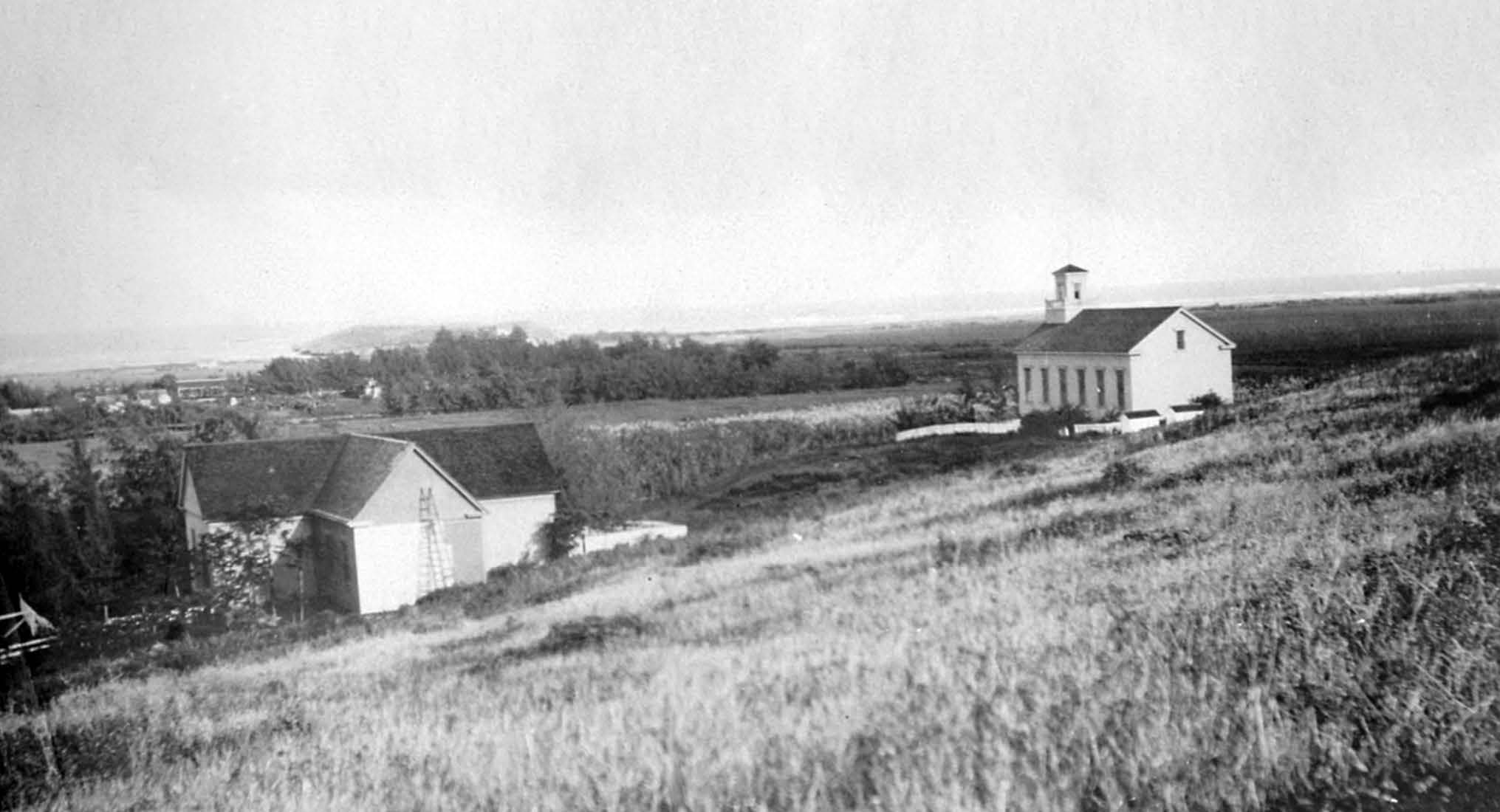

On 1 June 1915, President Joseph F. Smith, accompanied by Elder Reed Smoot and Bishop Charles W.

On 1 June 1915, President Joseph F. Smith, accompanied by Elder Reed Smoot and Bishop Charles W.

Nibley, walked the short distance from the mission home (far left) to the Lāʻie Chapel (far right), where

the prophet dedicated the site for the construction of a temple. Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives.

Regarding the contents of the dedicatory prayer, Bishop Nibley said, “President Smith asked the Lord that His Spirit might hover over and consecrate, and dedicate, and hallow that ground.”[5] And Elder Smoot later added: “I never saw a more beautiful night in all my life; the surroundings were perfect. . . . I have heard President Smith pray hundreds of times. . . . But never in all my life did I hear such a prayer. The very ground seemed to be sacred, and he seemed as if he were talking face to face with the Father. I cannot and never will forget it if I lived a thousand years.”[6]

Having been gone under an hour, the three Brethren returned to the mission home, where members, unaware of what had just occurred, were waiting patiently on the front lawn to present a program in honor of their departing guests.

Description of Temple Site

Elder John A. Widtsoe described the temple site as “the top of a hill, sloping rather gently to the north, south and east, and backed on the west by [a larger] green-covered coral reef [hill].” And of the surrounding area he noted:

Half a mile eastward from the temple site the lazy waves of the Pacific Ocean wash the sand-covered shore—a mile westward, rise the high, jagged, green mountains. . . . Between the temple and ocean and mountains lie well cultivated fields of sugar cane, kalo [taro] and other crops. High on the foothills can be seen the regular lines of the pineapple fields. Dotting the landscape . . . are groves of trees and palms, cocoanut, papaya, mango, banana. . . .

To the north, a block or two, can be seen the buildings of the mission headquarters. . . . Below the temple [site], and a little to the north lies the little village of Laie, with its pretty cottages, flower gardens and quiet streets. Now and then can be heard . . . the Oahu railroad, as it draws a train load of sugar cane or pineapples to the neighboring factory.

Over all hangs the blue sky, and an everlasting summer.[7]

Reasons for Choosing the Site

Other than Bishop Nibley’s suggestion that the location of the Lāʻie Chapel (I Hemolele) would be a good place to build the temple, as well as the unanimous agreement of the three leaders to dedicate that site, no reasons for why that specific location was chosen are on record. However, choosing that site made sense for several reasons. Only two years earlier, Bishop Nibley and his counselors in the Presiding Bishopric had asked potential architects for the Alberta Temple to prepare their drawings “for a structure on an eminence facing the east, and with a comparatively gentle slope.”[8] Similarly, the Lāʻie Chapel already faced east, and as noted in Elder Widtsoe’s description, it was slightly elevated and could be seen for some distance from the lower plane that extended to the ocean, and though elevated, the site was very accessible.

Furthermore, the site was already owned by the Church, and its proximity to the mission home/

A Promise

The dedicated temple site where the chapel then stood is on a small hill gently sloping to the east

The dedicated temple site where the chapel then stood is on a small hill gently sloping to the east

overlooking the community of Lāʻie and the ocean beyond. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The next day the prophet and his party departed Lāʻie for Honolulu, and a few days later they would set sail for home “after a very enjoyable visit in Hawaii of sixteen days.”[9] Although no one besides President Smith, Elder Smoot, Bishop Nibley, and President Woolley likely knew of the private dedication of the temple site, the prophet appears to have indicated the certainty of the temple to his longtime friend “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi before his departure. Elder Isaac Homer Smith, then serving in Honolulu, recorded his recollection that “he [the prophet] promised her on this occasion that she would live to receive her blessings in the House of the Lord.”[10] Likely shared out of love and deep appreciation for her unwavering devotion, this promise would prove to be a tender blessing for her.

First Presidency and Twelve Approval

On 17 June 1915, the day after returning to Salt Lake City, President Smith met with the First Presidency and the Twelve. “I sprung the proposition to build a small temple at Laie in the interests of our people of the islands of the Pacific,” wrote President Smith, “and it met with a warm approval by the entire council.”[11]

Apparently President Smith also discussed the temple’s construction with Ralph E. Woolley, President Samuel Woolley’s son.[12] Age twenty-nine, Ralph had completed a degree in engineering a year earlier and was working in Utah. The history of the Hawaiian Mission records that Ralph arrived at Lāʻie on 7 August, nearly a month before the temple was officially announced, “to do engineering on the plantation and on the new temple to be erected.”[13] Shortly thereafter, in a confidential letter to President Woolley dated 17 August, President Smith confirmed his intent “to make public announcement of the Sacred building . . . during our October conference.”[14]

Public Announcement of the Temple

In the opening session of general conference on 3 October 1915, President Joseph F. Smith concluded his remarks with a brief report of the progress being made on the construction of the temple in Alberta, Canada. He then rhetorically asked his audience why the Church was building that temple. President Smith responded with the story of a young man from northern British Columbia who had recently returned from a mission almost penniless. Shortly after his return, he found a virtuous woman to marry, but he lacked the means to travel to a temple to be sealed.[15] Having illustrated the need for temples outside Utah, President Smith then said the following:

Now, away off in the Pacific Ocean are various groups of islands, from the Sandwich Islands down to Tahiti, Samoa, Tonga, and New Zealand. On them are thousands of good people . . . of the blood of Israel. When you carry the Gospel to them they receive it with open hearts. They need the same privileges that we do, and that we enjoy, but these are out of their power. They are poor, and they can’t gather means to come up here to be endowed, and sealed for time and eternity, for their living and their dead, and to be baptized for their dead. What shall we do with them? . . .

Now, I say to my brethren and sisters this morning that we have come to the conclusion that it would be a good thing to build a temple that shall be dedicated to the ordinances of the house of God, down upon one of the Sandwich Islands, so that the good people of those islands may reach the blessing of the House of God within their own borders. . . .

It is moved that we build a temple at Laie, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii. All who are in favor of it will please manifest it by raising the right hand [all hands raised]; contrary minded by the same sign. I do not see a contrary vote.

I want you to understand that the Hawaiian mission, and the good Latter-day Saints of that mission, with what help the Church can give, will be able to build their temple. They are a tithe-paying people, and the plantation is in a condition to help us. We have a gathering place there where we bring the people together, and teach them the best we can, in schools and under the various auxiliary organizations of the Church. I tell you that we (Brother Smoot, Bishop Nibley and I) witnessed there some of the most perfect and thorough Sunday School work on the part of the children of the Latter-day Saints that we had ever seen. God bless you. Amen.[16]

House of Israel

In his reasoning, President Smith extolled the faith of Church members throughout the Pacific, making clear that the temple in Hawaiʻi was intended to serve members across Polynesia. Furthermore, the prophet reassured a debt-weary Church that this temple would be prudently financed. But at the core of President Smith’s reasoning for a temple in Hawaiʻi was his appeal to fairness and equality: “They need the same privileges that we do, and that we enjoy.”

Also notable is the prophet’s specific reference to Pacific Islanders as “the blood of Israel.” As previously mentioned, shortly after the arrival of the Church in the Pacific, missionaries and Church leaders connected Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders with the house of Israel.[17] God seeks to gather Israel for several reasons: to learn the teachings of the gospel, strengthen one another, and organize themselves to preach the gospel to others. What’s more, he gathers them so they can build temples in which to perform sacred ordinances.[18] Moreover, the specific connection of Pacific Islanders to Joseph, son of the patriarch Jacob, carries with it particular duties. The tribes of Joseph’s sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, are to be gathered first and are then to help gather others into the covenant (see Joseph Smith Translation, Genesis 48:5–11; Deuteronomy 33:16–17; Doctrine and Covenants 133:30–39).[19] As will be seen, a temple in Hawaiʻi would prove providential to island members in their duty to extend the gospel covenant in its fulness to other nations.[20]

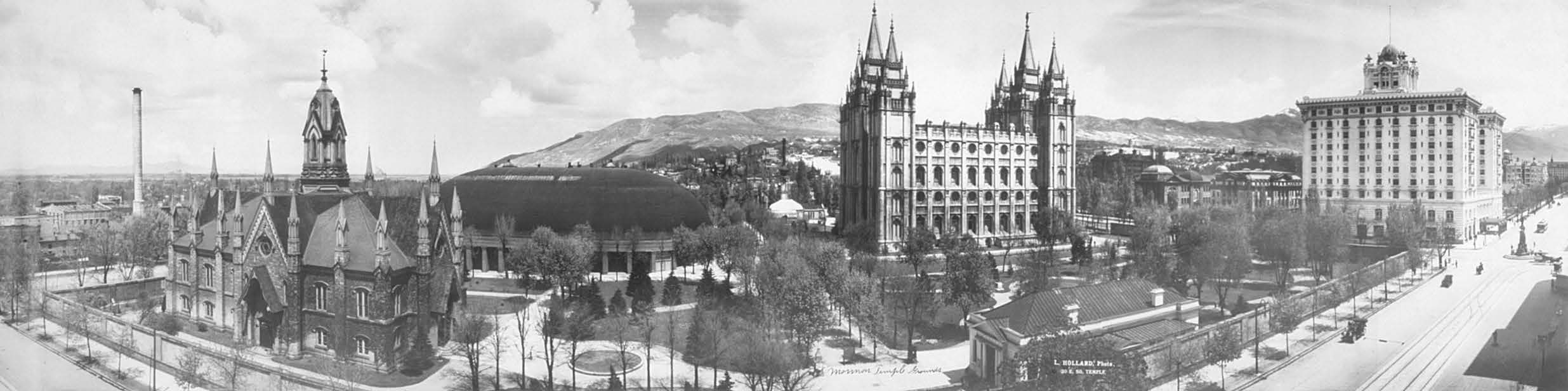

At general conference on 3 October 1915, President Joseph F. Smith’s proposal that a temple be built in Hawaiʻi was unanimously received. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

At general conference on 3 October 1915, President Joseph F. Smith’s proposal that a temple be built in Hawaiʻi was unanimously received. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Reaction to the Announcement

Reaction to President Smith’s conference announcement that a temple would be built in Hawaiʻi was tremendous. Speaking later in the same conference, President Samuel Woolley stated, “I have felt for years that there would be a temple there, and I have put forth what effort the Lord has given me to that end trying to build up and beautify that sacred land.” He told those in attendance that the land of Lāʻie, upon which the temple would be built, was considered a “city of refuge” (puʻuhonua) by ancient Hawaiians and that it will now be “an eternal city of refuge” to their posterity. Woolley then concluded, “The spirit of temple work, looking after themselves and their dead, has been in the hearts of [Hawaiians] for years, and now we have voted to build a temple.”[21]

Through the kindness of a Honolulu newspaper reporter, word of the temple announcement arrived in Lāʻie that same day, just in time to be announced at the conclusion of a Sunday School conference (378 present). Orson Clark, a missionary, recorded, “Such a beautiful end to one of the most interesting conferences. . . . Many people had been working and preparing to go to the House of the Lord, and now their dreams were to be realized sooner than they anticipated.”[22] Capturing the voice of many, Native Hawaiian Lyons Baldwin Nāinoa, a longtime resident of Lāʻie, declared, “We have prayed for a long time that the Lord would help us to go to Zion (Utah), and now we have the temple brought to our own land. Let us work day and night.”[23]

The day after the announcement, the Deseret News ran an article stating: “It will be sixty-five years next December since the first missionaries . . . set foot upon these lovely isles of the Pacific. . . . The result is written in one of the brightest chapters of Church history. Much of the blood of Israel was found, thousands were brought into the covenant. . . . Probably no part of the earth has yielded a richer harvest of human souls, in proportion to size and population, than this same group of islands in the Pacific. . . . It is entirely appropriate, therefore, that the site of the first temple beyond the limits of continental America should be fixed for the Hawaiian Islands.”[24]

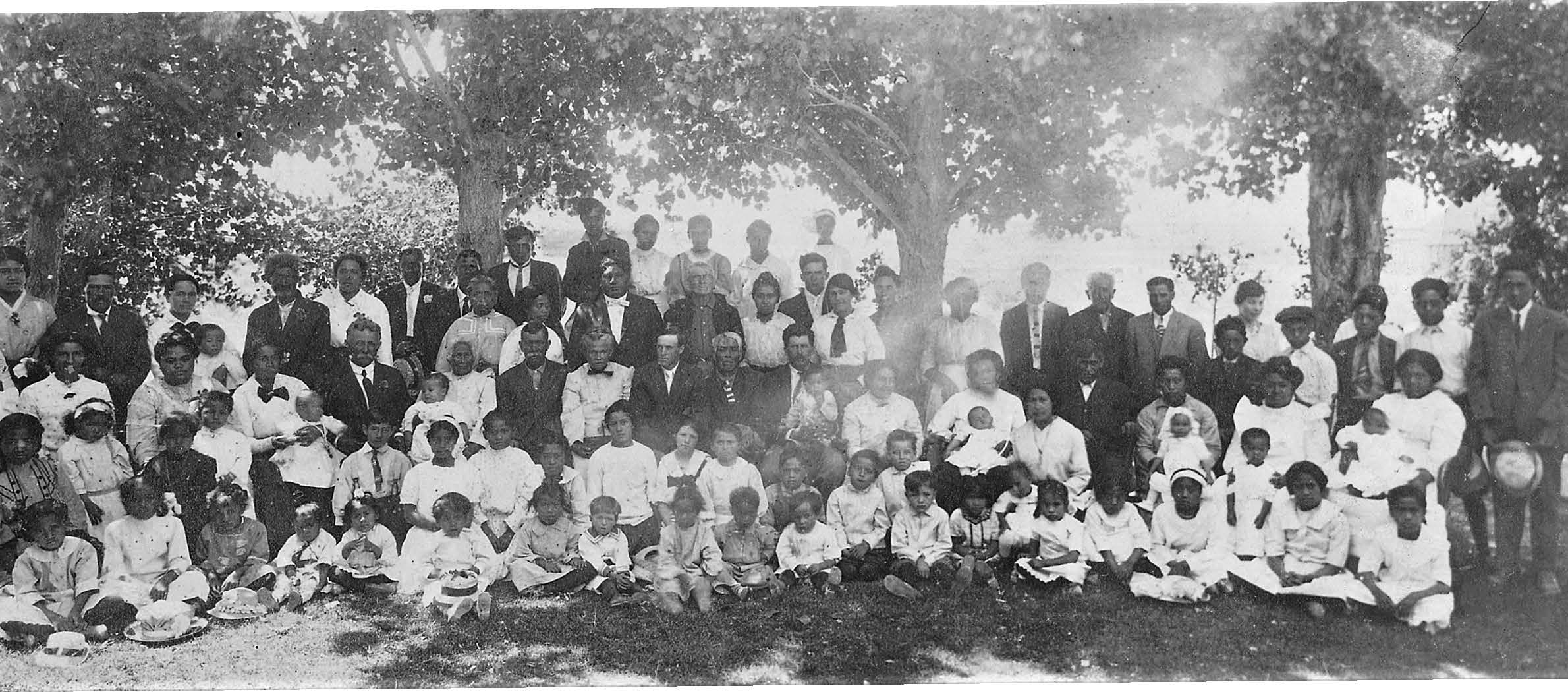

Perhaps most dramatically affected by the temple’s announcement was the Polynesian settlement of Iosepa, seventy-five miles west of Salt Lake City in Skull Valley, Utah. As mentioned, the Iosepa colony was established in 1889 largely by Native Hawaiian members who had gathered to Utah seeking temple blessings. Closely acquainted with these Saints, President Joseph F. Smith paid them a visit after the conference. Iosepa resident Maryann Nawahine recalled: “He told us to return to the warm lands of our ancestors and that a temple would soon be built there. ‘I will soon die, and I don’t know what will become of you Hawaiians,’ he said. So the following year, 1916, we returned to Laie.”[25] Of the same visit, Native Hawaiian John E. Broad noted, “He did not pressure us to go, to return to Hawaii. No, he gave us that privilege if we wanted to return.”[26]

Two observations are worth making. First, both generations at Iosepa—the older generation that came from Hawaiʻi and the generation born at Iosepa who left the colony—experienced the sacrifice of leaving the place of their birth in large measure for temple blessings. Second, the Iosepa Saints assuredly factored into Joseph F. Smith’s decision to build a temple in Hawaiʻi. President Smith was intimately aware of the Iosepa Saints’ faith and long-demonstrated willingness to sacrifice for temple blessings. And he specifically tied his reasoning for their return to Hawaiʻi to the temple’s construction and proffered blessings. To the Iosepa colony’s legacy of faith, it is safe to add a considerable contribution to the realization of the Hawaii Temple.

Looking back on the effect this temple announcement had on the Church, the Relief Society Magazine said that upon the temple’s announcement “a psalm of praise arose in the heart of every Latter-day Saint. And every step of the way for its erection and completion has been observed with keen interest since that auspicious day.”[27] A description of this “keen interest” in the construction and completion of the temple follows.

Iosepa Saints circa 1910. Shortly after the temple’s announcement, the prophet personally visited the Polynesian colony at Iosepa, Utah, recommending the Saints return to the islands and assist with the temple. They did so, and the Iosepa Ranch was sold in 1917. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Iosepa Saints circa 1910. Shortly after the temple’s announcement, the prophet personally visited the Polynesian colony at Iosepa, Utah, recommending the Saints return to the islands and assist with the temple. They did so, and the Iosepa Ranch was sold in 1917. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Notes

[1] See Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 310.

[2] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 310.

[3] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 310. President Joseph F. Smith later added: “I want to say to you that on the first of June, 1915, while on the islands with Brother Reed Smoot and Bishop Charles W. Nibley and the president of the mission there, and others of the elders, we talked over this matter, and we agreed—that is, Brother Smoot, Bishop Nibley and I agreed—that we would recommend the building of a temple in our settlement at Laie, and in pursuance of this agreement on our part, subject, of course, to the confirmation of the Council of the Twelve and of the Church, we went out upon the ground that we thought would be suitable on which to build a temple, and in the shades of evening we offered a prayer to the Lord and we dedicated the ground for that purpose, on condition it was approved by the presiding authorities of the Church and by the Church itself.” “Conference Address by President Joseph F. Smith,” Millennial Star, 4 November 1915, 694.

[4] Harvard Heath, ed., In the World: The Diaries of Reed Smoot (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1999), 273–74.

[5] Charles W. Nibley, Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 17 February 1920, 273.

[6] Reed Smoot, in Conference Report, October 1920, 137.

[7] John A. Widtsoe, “The Temple in Hawaii: A Remarkable Fulfilment of Prophecy,” Improvement Era, September 1916, 953–54.

[8] “Approved Design for Temple in Alberta Province: Pope & Burton Awarded First Honors in Architects’ Competition,” Deseret Semi-Weekly News, 2 January 1913.

[9] Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 5 June 1915.

[10] Isaac Homer Smith, in Brief History of the Life of Isaac Homer Smith, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[11] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 311.

[12] This is according to Romania Woolley, Ralph’s wife. See Eva Newton, “Finishing the Hawaii Temple” (1991), BYU–Hawaii Archives, 335.

[13] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 7 August 1915.

[14] President Joseph F. Smith to Samuel E. Woolley, 17 August 1915, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[15] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, 3 October 1915. For a more detailed account of his remarks, see “Conference Address by President Joseph F. Smith,” Millennial Star, 4 November 1915, 689–94.

[16] Smith, in Conference Report, 3 October 1915. For a more detailed account of his remarks, see “Conference Address by President Joseph F. Smith.”

[17] As previously noted, there are several possibilities of how, when, and to what extent a remnant of the house of Israel found its way into the Pacific Islands. See chapter 1, notes 24 and 25.

[18] See “The Gathering of the House of Israel,” chap. 42 in Gospel Principles (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2011), 245–50.

[19] See “The Scattering and the Gathering of Israel,” chap. 24 in Doctrines of the Gospel Student Manual (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2000), 64–66.

[20] Further, directly linking Pacific Islanders with the biblical promises given to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and more specifically to Joseph, may offer some reason for the early arrival of the Church in the islands, the ready acceptance of the restored gospel by so many, and now the remarkably early building of a temple in their midst. See R. Lanier Britsch, “The Conception of the Hawaii Temple,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 9, no. 1 (1988), https://

[21] Samuel E. Woolley, president of the Hawaiian Mission, in Conference Report, October 1915, 110–12.

[22] Orson Clark, mission journal, 3 October 1915. Special thanks to Dean Ellis for suggesting this source.

[23] Lyons Baldwin Nāinoa, minutes of regular annual conference of the Hawaiian Mission, 6 April 1916, CHL, 33–34, quoted in Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011), 109.

[24] Quoted in Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 26 October 1915, 279.

[25] Henry and Maryann Nawahine, interview by Clinton Kanahele, 20 July 1963, box 5, folder 6, Jerry Loveland Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[26] John E. Broad, interview by Clinton Kanahele, 13 June 1970, Lāʻie, Hawaiʻi, MSSH 550, Clinton Kanahele Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[27] “Dedication of the Hawaiian Temple,” Relief Society Magazine, February 1920, 79.