Temple Grounds and Completion

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Temple Grounds and Completion," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 109–128.

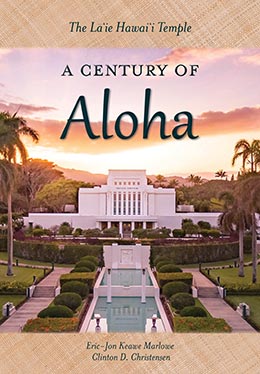

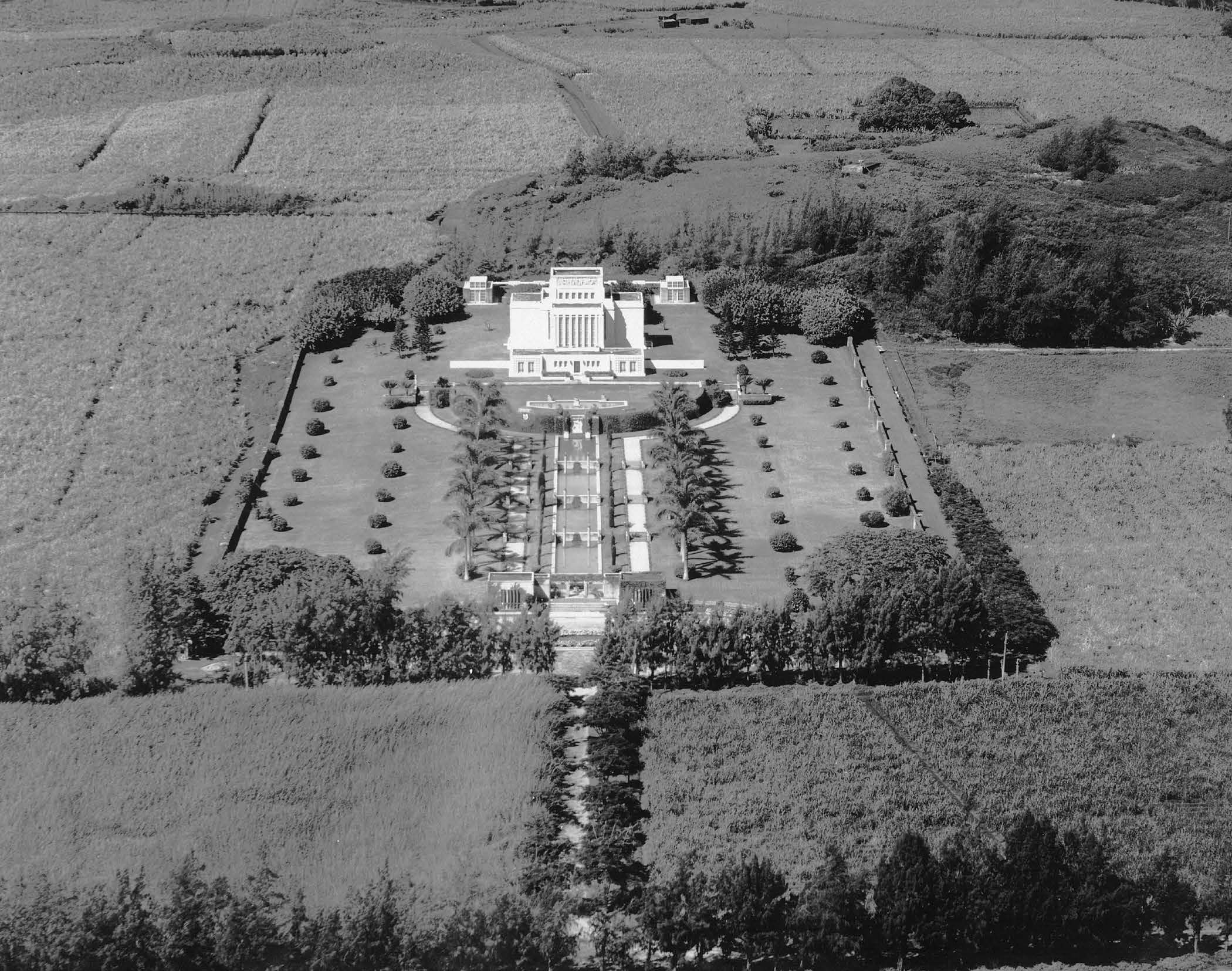

In the five acres enclosed by a new lava rock wall, architect Harold Burton designed a beautiful setting that would come to enhance the temple’s monumental character. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In the five acres enclosed by a new lava rock wall, architect Harold Burton designed a beautiful setting that would come to enhance the temple’s monumental character. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In April 1918, the Deseret News ran an article entitled “Temple Complete: Attention Centered Now on Landscape.”[1] By this time, work on the temple grounds was already well underway.[2] Architect Harold Burton had designed a beautiful setting around the temple that would enhance its monumental character.[3] Enclosing the five-acre grounds was “a four-foot wall of lava rock, buttressed at intervals by solid concrete blocks.”[4] Within these sacred grounds would be three modestly rising, rectangular terraced pools with cement walkways on either side leading to the temple.[5] The most elevated of these pools connected to a concrete wall (now covered in vines) ten feet high, forming a semicircular terrace immediately around the entrance to the temple and containing an additional pool with a fountain. This semicircular wall was also part of the Alberta Temple design and was intended “to emphasize the height of the [temple] structure and to provide a secluded setting in keeping with the purpose of the edifice.”[6] Furthermore, on the hillside directly behind the Hawaii Temple, two small fern houses conforming to the architectural style of the temple were constructed, along with a lengthy pergola extending between them.

Statuary

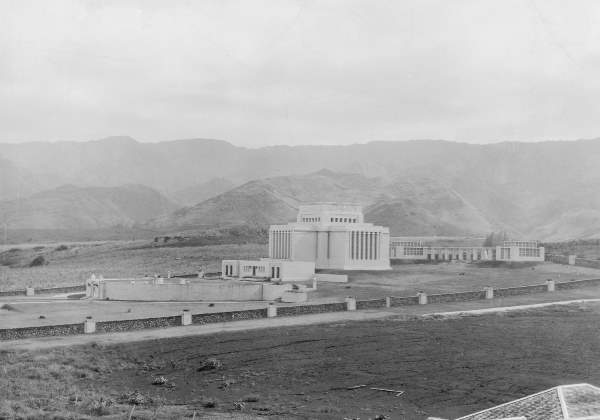

At the head of three pools is a bold relief panel designed and sculpted by Avard Fairbanks to honor motherhood. Courtesy of Church History Library.

At the head of three pools is a bold relief panel designed and sculpted by Avard Fairbanks to honor motherhood. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In his design of the temple landscape, Harold Burton had designated two areas of special consideration for statuary: one, a fountain at the head of three pools; the other, a statue at the entrance to the temple grounds. Because Avard Fairbanks’s work on the friezes was concluding in late 1917, Burton and President Samuel Woolley asked him to make studies of two sculptures—one to represent Hawaiian motherhood and the other to show Lehi blessing his son Joseph.[7]

At the head of the three pools, slightly recessed in the semicircular retaining wall and framed with vines, is a panel in bold relief depicting a Hawaiian mother and her children. “I designed a group to represent Hawaiian Motherhood,” Avard explained, “or, as it is called ‘Maternity.’ . . . Motherhood was represented by a Hawaiian lady with a great shell, and she was pouring water out of this great shell to her children.” Avard considered the water coming from the shell to represent the “Fountain of Life” that a mother offers her children.[8]

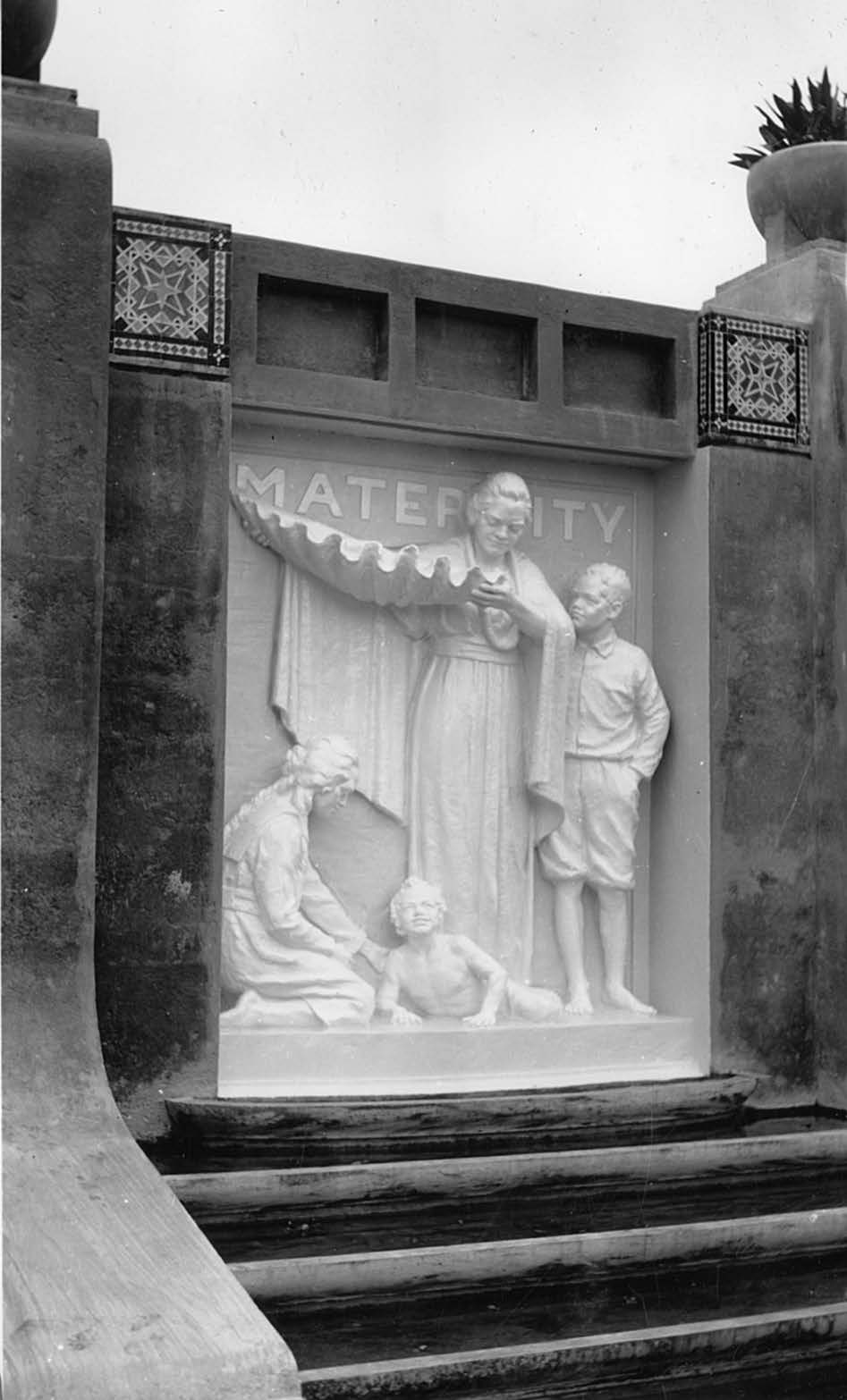

The other sculpture produced was Lehi Blessing Joseph. Speaking in the October 1917 general conference overflow meeting, President Samuel Woolley shared his belief that the building of a temple in Hawaiʻi was “fulfillment of the promise that the Lord made to Lehi who . . . in blessing his son Joseph, promised him that all of his seed would not be lost.” Woolley further suggested that a remnant of Joseph’s descendants ended up in Hawaiʻi, Samoa, New Zealand, and other Pacific Islands, and that the Lord “sent his servants there in an early day in our history . . . to fulfill his promises.”[9] Upon President Woolley’s return to Hawaiʻi, Burton discussed with him the inclusion of a statue within the temple grounds, and it was decided to include one of Lehi, the first Book of Mormon prophet, blessing his son Joseph.

With reference to 2 Nephi 3:3–5, this statue of Lehi blessing Joseph symbolizes the early latter-day gathering of Israel in Hawaiʻi and across Polynesia. Courtesy of Church History Library.

With reference to 2 Nephi 3:3–5, this statue of Lehi blessing Joseph symbolizes the early latter-day gathering of Israel in Hawaiʻi and across Polynesia. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Avard’s larger-than-life creation was placed at the front entrance to the temple grounds, but shortly thereafter it was moved to the back of the temple between the two fern houses.[10] It now resides in the west courtyard of the temple visitors’ center. According to J. Leo Fairbanks, the statue “symbolizes God’s promise to Lehi’s son realized . . . through the Hawaiian people.”[11] Although we may not know exactly how this ancestral connection occurred, the statue remains symbolic of the latter-day gathering of Israel that has taken place, and continues to take place, in Hawaiʻi and across Polynesia.

Visitors’ Bureau

Two small buildings reflecting the unique architecture of the temple were built just below the terraced pools on either side of the entrance gates. They were fitted to receive visitors and to function as a bureau of information. Years earlier, in 1902, the Church established its first visitors’ bureau (later called a visitors’ center) on Temple Square in Salt Lake City to provide tourists with accurate information about Church beliefs and history.[12] Evidently the Visitors’ Bureau at the Hawaii Temple was the second in the Church and the first built simultaneously with the construction of a temple. In its early years, missionaries often staffed the Visitors’ Bureau during the day and then officiated in the temple in the evenings.

Two small buildings on either side of the entrance gates were fitted to receive visitors. Originally functioning as a bureau of information, they were a forerunner to visitors’ centers commonly used throughout the Church today. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Two small buildings on either side of the entrance gates were fitted to receive visitors. Originally functioning as a bureau of information, they were a forerunner to visitors’ centers commonly used throughout the Church today. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Inclusion of a visitors’ bureau in the original design of the temple grounds was perceptive. Although sugarcane was still Hawaiʻi’s economic engine at the time, the writings of men like Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson had stoked interest in Hawaiʻi, and tourism was on the rise. In the decade that followed, William Waddoups, first temple president, wrote: “Thousands of tourists visit the temple grounds at Laie every year. It is one of the beauty spots of the islands and attracts almost all of the visitors who come to our shores. Free literature and guides are available to our visitors. We feel that this is one of the very important missionary opportunities offered to our Church.”[13] The small edifices that received all those visitors (occasionally enhanced over years) would serve as the Visitors’ Bureau until 1963, when they would be replaced with the extensive visitors’ center seen today.

Vegetation

The architects worked out a brilliant design for the temple grounds, and the maturing gardens served to enhance the temple’s beauty. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The architects worked out a brilliant design for the temple grounds, and the maturing gardens served to enhance the temple’s beauty. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The Relief Society sisters, led by Ivy Apuakehau, planted grass across the five-acre temple grounds.[14] Zipporah Stewart recorded that the “soil was prepared, and all the dear sisters, myself included, crawled on our hands and knees. The roots were put into the soil and pressed down by hand about three or four inches apart. . . . No seeds were sown.” Sister Stewart continued, “For two or three weeks these sisters could be seen crawling along each with a basket of roots. The native sisters wore their long, light-colored holoku dresses. It was a sight to behold, and how our legs and back did ache when night came.” Of the completed project, she added, “It didn’t look very good at first, but in the warm moist air and Hawaiian sunshine and rain, it soon thickened up and looked like a lovely green carpet all over the ground. I have always felt a degree of pride when I’ve seen it knowing I was a small part of that project.”[15]

The architects worked out a brilliant design for the temple grounds, and the maturing gardens served to enhance the temple’s beauty. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The architects worked out a brilliant design for the temple grounds, and the maturing gardens served to enhance the temple’s beauty. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Noticeable in photos taken at the temple’s dedication in 1919, the grounds were devoid of trees, shrubbery, and other flora. These were added in 1920. Although not a Church member, Joseph Rock, the Territory of Hawaiʻi’s first official botanist and a faculty member of the University of Hawaiʻi at the time, generously volunteered his services in planning the landscape gardening of the temple grounds.[16] Rock’s involvement led Duncan McAllister, the Hawaii Temple’s first recorder, to correctly note, “We confidently anticipate that, in due course of time, these grounds will be attractively beautiful.”[17]

Success of the Temple Grounds

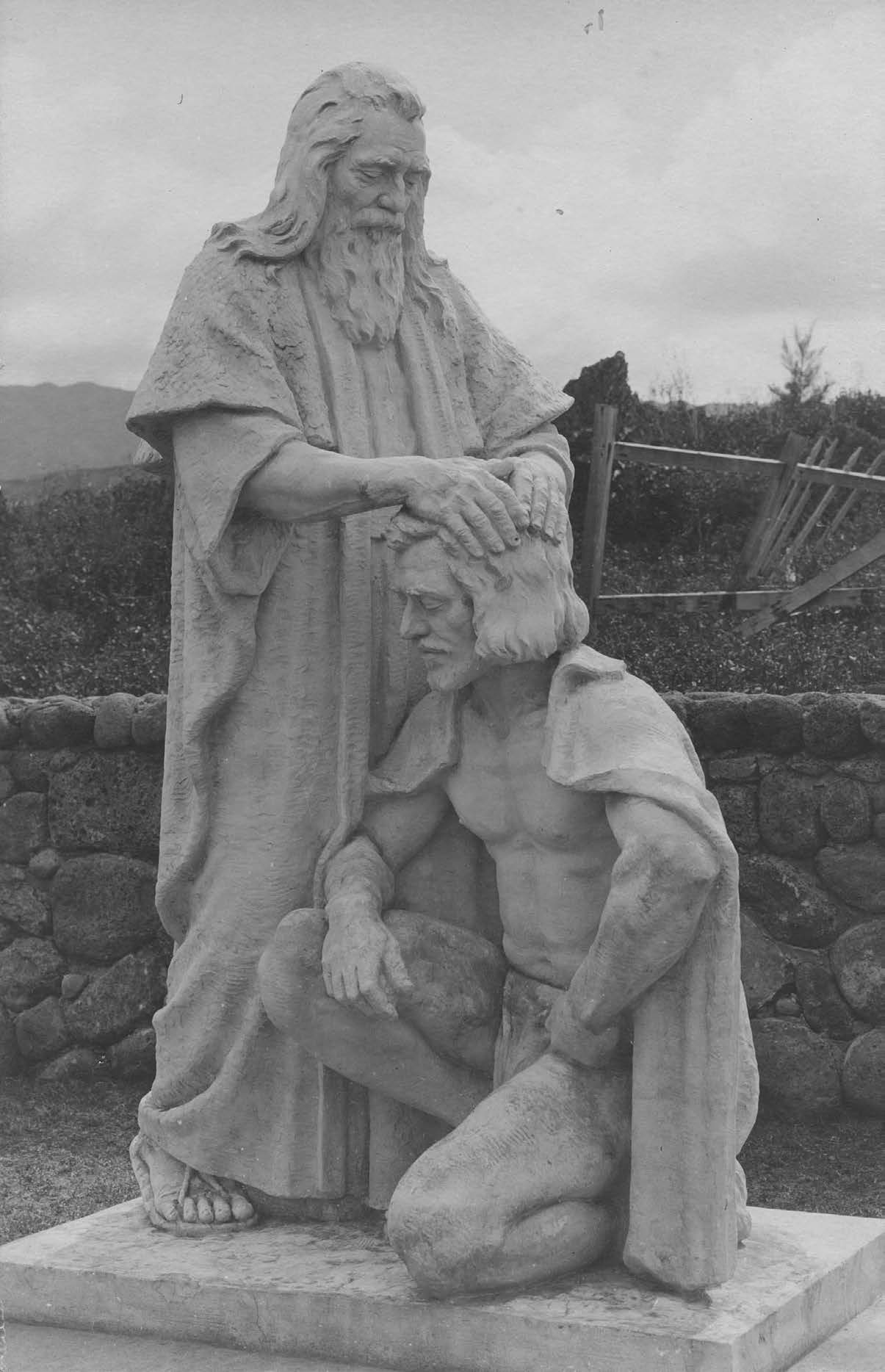

As previously mentioned, the temple itself was relatively small (originally 10,500 square feet) and was built amid the Church’s sprawling plantation, with mostly sugarcane surrounding it.

As the temple took shape in this open landscape, it must have looked small and lonely. The architects worked out a brilliant design for the temple grounds to remedy this impression. Their grand conception of the temple as the climax of an arrangement of terraces, reflecting pools, waterfalls, and tropical plants arranged along a formal axis was one of their most powerful ideas—a concept that would take many years of patient care to realize completely. From the driveway and gatehouses [visitors’ bureau] at the lower end of the site to the delicate fern houses and pergola behind the temple, everything was composed in a unified symmetrical scheme. . . . As the gardens have matured and the outbuildings have expanded, the temple has continued to dominate its surroundings.[18]

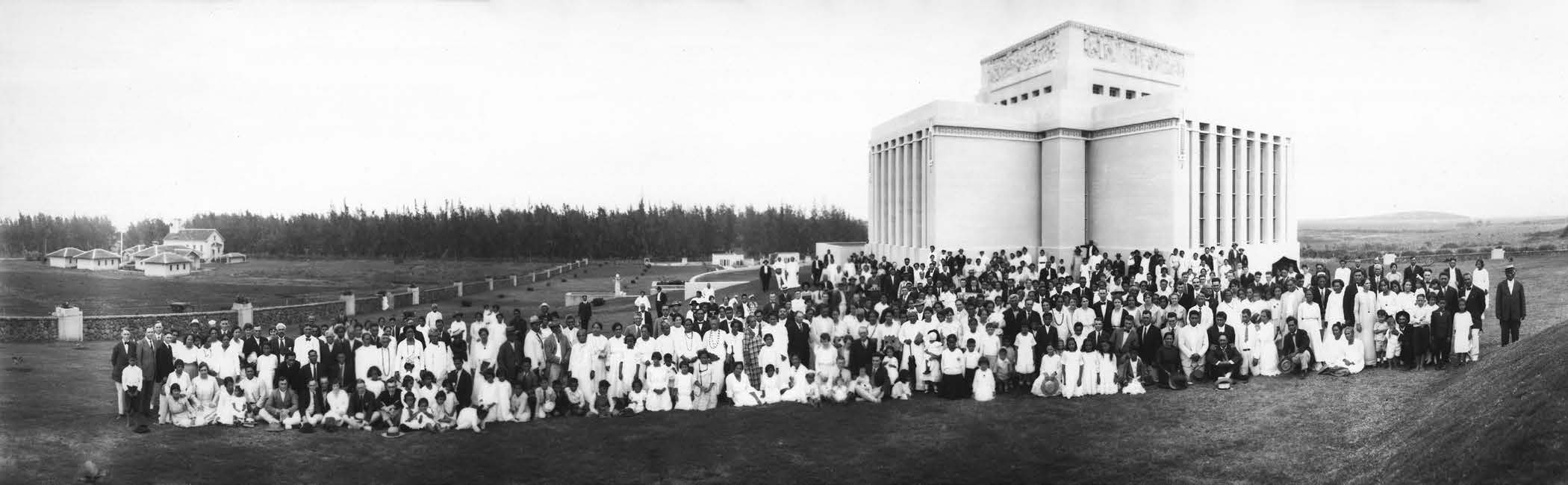

President Heber J. Grant, in his 1919 dedicatory prayer for the Hawaii Temple, asked that “all who come upon the grounds which surround this temple [would] feel the sweet and peaceful influence of this blessed and hallowed spot.”[19] Few at that time could have envisioned the millions that would have such an experience over the next century on these temple grounds.

The Triumph of Construction

There is an account related to the construction of the temple that has attracted considerable attention over the years. The story goes that as the temple was under construction, the lumber that was being used ran out. Lumber was necessary to create and buttress the forms into which concrete was poured, to provide extensive scaffolding, and to do other necessary jobs, and this shortage threatened to halt the work. Building supervisor Ralph Woolley—and perhaps others associated with the work—prayed about this challenge. A day or two later, word spread through the village that a ship had run aground on a reef off Lāʻie. This ship was carrying lumber and needed to unburden itself of this cargo in order to free itself from the reef. Community members helped gather and haul the floating lumber to the temple site, and construction resumed. This story has commonly been retold to illustrate the Lord’s hand in the construction of the temple and his willingness to answer prayer.[20]

The quality of the Hawaii Temple’s design, the artistic success of its decorations, and the beauty and arrangement of its gardens combine to produce what has been called an “artistic miracle.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The quality of the Hawaii Temple’s design, the artistic success of its decorations, and the beauty and arrangement of its gardens combine to produce what has been called an “artistic miracle.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

As striking as the lumber story may be, the much larger though slower-moving miracle was the entire construction of the temple. The Hawaii Temple was essentially built without the use of heavy equipment. And although they were talented and teachable, most of the Hawaiian Church members who built the temple were, at least initially, unskilled in the trades required to construct such a modern building. Further, many of the specialized workers were young (architect Harold Burton, construction supervisor Ralph Woolley, cement builder Walter Spalding, sculptor Avard Fairbanks, and artist LeConte Stewart were all in their twenties), and though they were well educated, they were relatively untested in the particular tasks the temple’s construction demanded. What’s more, from moving the chapel to make way for the temple (January 1916) to the planting of grass on the temple grounds (June 1918), construction took about two and a half years. In contrast, the simultaneous construction of the Alberta Temple took ten years (1913 to 1923) to complete.[21]

That the building of the Hawaii Temple could be achieved with such quality while using mostly unskilled labor in markedly remote conditions without the use of heavy equipment, be financed entirely in Hawaiʻi, and be completed within two and a half years while enduring various delays really was quite miraculous. However, the ultimate miracle is what that cumulative effort, with divine assistance, produced—a magnificent edifice eminently suited to its purpose as a house of the Lord. As Paul Anderson rightfully concludes:

The enduring value of the temple builders’ work is evident in the temple’s ability to inspire awe and admiration through the decades. Its design achieved a sense of timelessness that has not gone out of fashion.

The temple and its grounds demonstrate the spiritual power of an artistic vision. . . . The quality of its design, the artistic success of its decorations, and the beauty and arrangement of its gardens have all combined to make it a memorable landmark for both the Church and Hawaiʻi. It is a kind of artistic miracle that in this remote place, at a time when relatively few Latter-day Saints lived outside Utah, the builders were able to make this small temple into a fitting symbol of their grandest spiritual hopes and ideals.[22]

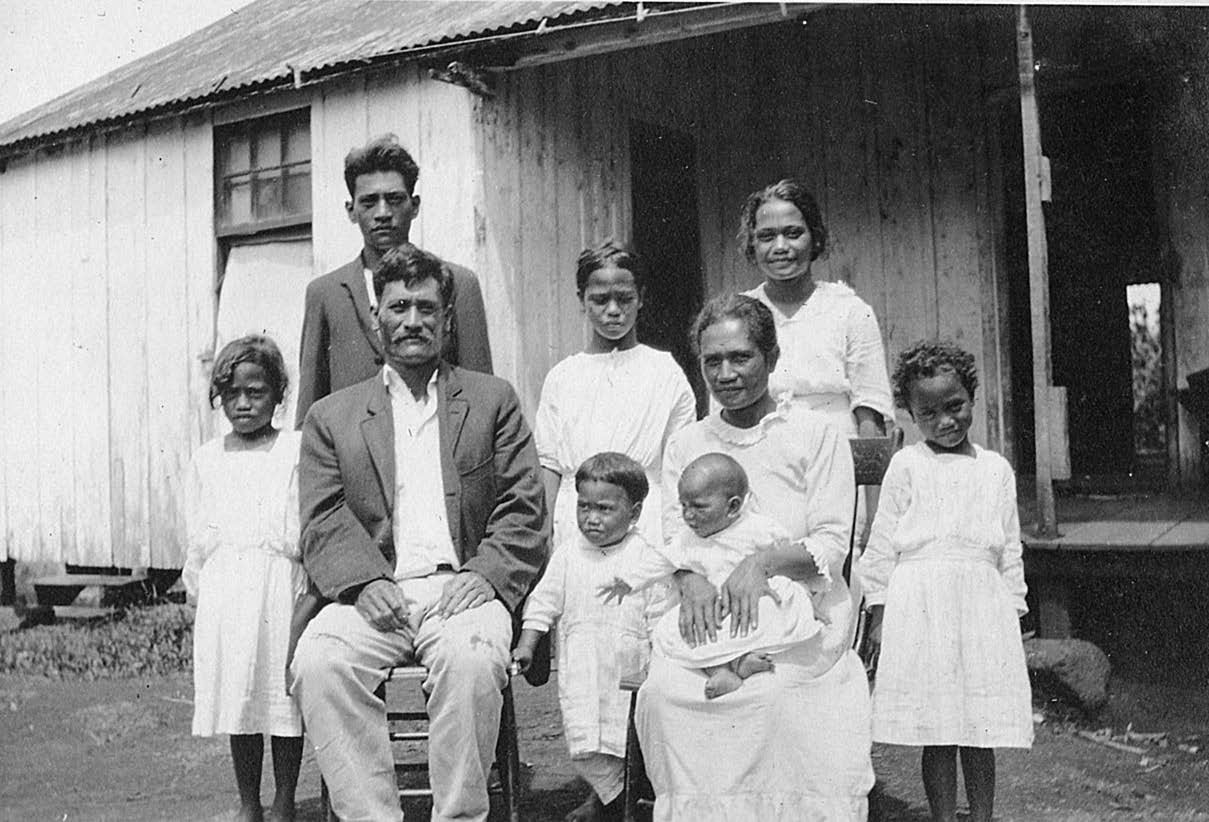

Honoring the Hawaiian Saints

The demographics of the Hawaiian Islands had changed rapidly over the years, so much so that by the time the temple was constructed Native Hawaiians made up only about 20 percent of the islands’ overall population.[23] Yet as previously noted, from the time the Church arrived in Hawaiʻi through the temple’s construction, Church membership in the islands was predominantly Native Hawaiian.[24] Although the Church demographics in Hawaiʻi would significantly change in coming years and the temple would soon serve an incredibly diverse and international membership, it was primarily the Native Hawaiian Saints’ faith, funding, and physical labor that built the temple, and fittingly the temple would first serve their ancestors.

Funding the temple

Virtually all funding for the Hawaii Temple came from tithing, donations, or plantation profits acquired in Hawaiʻi.[25] After the temple was announced, many native members who had been saving to attend the temple in Utah promptly donated those savings to the Hawaii Temple’s construction.[26] Then in the mission-wide conference following the temple’s announcement, President Samuel Woolley challenged each member to donate five dollars—a substantial sacrifice at the time.[27] Shortly after this challenge was issued, John A. Widtsoe (later called as an Apostle in 1921) and his wife Leah arrived in Hawaiʻi for an extended stay. During this time he observed:

All are making their donations to the temple. The children save their pennies, and the parents their dollars. . . . The widow gives her mite, and the poor find it possible to give. . . . Concerts and other entertainments and bazaars are held to secure monies with which to increase the temple fund. One group of sisters go into the mountains for bamboo and lauhala, which they make into fans, pillows, mats and other useful articles, which are sold. . . . Several Relief Societies [make] quilts, laces, mats and many other things are made, later to be sold at bazaars held for the benefit of the temple. And all this is done joyously.[28]

Among the Hawaiian Saints eager to contribute their share of the temple were those living at the Kalaupapa leper colony on the island of Molokaʻi. “They knew they couldn’t go to the temple,” said missionary W. Francis Bailey, “but from what I can learn they were the first to meet their assessment on the temple. It was a very sizable amount.”[29]

Concerts and other forms of entertainment provided by members were among a variety of ways the Hawaiian Saints raised funds for the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Concerts and other forms of entertainment provided by members were among a variety of ways the Hawaiian Saints raised funds for the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The cumulative effect of these donations and fundraisers exceeded President Samuel Woolley’s challenge, raising approximately $60,000 (more than six dollars per member).[30] Giving voice to the pervasive generosity and often meager means by which the Hawaiian Saints did this, Elder Ford Clark, a missionary in the Hawaiian Mission from 1917 to 1920 who was deeply moved by a member giving her last forty cents in care of him and his companion, simply concluded, “But that is a Hawaiian over and over and I see it every day.”[31]

Though member donations were substantial, the total cost of the temple was somewhere between $215,000 and $256,000.[32] Rather remarkably, President Woolley was able to make up the remaining cost of the temple through profits from the Lāʻie Plantation, which employed mainly members of the Church at that time. As mentioned, it was fortuitous during the construction of the temple that sugarcane prices were historically strong and consistent, thus providing a steady and substantial stream of revenue for constructing the temple.[33] Thus all funding for the Hawaii Temple was essentially contained to the Hawaiian Islands.

Although unable to attend the temple, Church members in the Kalaupapa leper colony on Molokaʻi were among the first to meet their donation challenge to help fund the construction of the temple. Photo of Kalaupapa by

Although unable to attend the temple, Church members in the Kalaupapa leper colony on Molokaʻi were among the first to meet their donation challenge to help fund the construction of the temple. Photo of Kalaupapa by

Forest and Kim Starr courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

creativecommons.org /

A monument of faith and labor

Many deserve credit for their contributions to the construction of the Hawaii Temple. For more than sixty years, dedicated missionaries and the support of patient Church leaders had helped lay the foundation of the Church in Hawaiʻi. President Woolley was particularly instrumental, and the various specialists involved in the actual construction also merit meaningful recognition, as do many more people. However, it is appropriate to emphasize again that the Hawaii Temple was principally built on the faith, donations, and physical labor of the Hawaiian Saints. As temple architect Hyrum Pope observed: “In the construction of this edifice the ideal which was ever held in mind was to erect a structure that would be as lasting as human skill could make it. . . . As it stands today complete in every particular, this temple is a lasting monument to the faith and devotion of the Hawaiian Saints.”[34]

For their ʻohana

The Hawaiian word ʻohana means “family”—not just the small nuclear family but rather what Dorothy Leilani Behling refers to as the “fully-extended generational family.” She explains that ʻohana is the “family of aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins of various numbers and degrees without which the Polynesian is heartsick and lonely. ʻOhana is the embracing, animating center of life—one’s family.”[35]

For the Kapaha family and their fellow Hawaiians, the temple is about ʻohana, “the embracing,

For the Kapaha family and their fellow Hawaiians, the temple is about ʻohana, “the embracing,

animating center of life—one’s family.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Just as within the Church one’s obligation to redeem the dead begins with his or her own immediate ancestry (ʻohana), it might be assumed that after death one’s first efforts to share the gospel in the spirit world would follow that priority as well. As mentioned, the Hawaiian race, which included numerous Church members, was decimated by disease in the 1800s. This was devastating for those who lost loved ones. Yet amid such loss, Hawaiian Church members, and the missionaries who served among them, were often comforted by the understanding that those deceased would now be furthering the gospel cause in the spirit world, particularly among their departed ʻohana. Sharing this feeling, Behling wrote, “I choose to believe . . . that some of the best of the newly converted children of Israel in Hawaii left this world to teach their ohana waiting in the spirit world.”[36]

For more than sixty years these departed Hawaiian members had been preaching to their ʻohana across the veil. Now their faithful descendants had built a temple that could consummate that labor. What’s more, many ancient Hawaiian names and ancestry had been preserved in chants and meles (songs) handed down through generations, and these records would be among the first work for the dead done in the Hawaii Temple. Of these conditions, Behling concluded:

I believe there was no place in all the world in 1919 that was any more prepared to support the work of a temple—with centuries of [ancestral] records, over [60] years of preparation by missionaries to the dead, and a tried and faithful membership—than Hawaii. The reward for this extraordinary effort was the Hawaii Temple.[37]

Gathering of Hawaiian Saints at the temple on 11 June 1920. Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives.

Gathering of Hawaiian Saints at the temple on 11 June 1920. Courtesy of Hawaii State Archives.

Notes

[1] Noted in Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 18 April 1918.

[2] Report of Progress, March 1918, in Correspondence and Reports Relating to the Building of the Laie, Hawaii Temple, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[3] Howard W. Burton to Randolph W. Linehan, 20 May 1969, Harold W. Burton Papers, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[4] Rudger J. Clawson, quoted in Duncan M. McAllister, A Description of the Hawaiian Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Erected at Laie, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1921). The Hui Lau Lima News reported: “These men drove teams of horses to the river beds in the mountains back of Laie and hauled [lava] rocks to the Temple site. . . . Smaller rocks were used in the wall around the Temple grounds.” Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957, MSSH 284, box 52, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 8.

[5] See Rudger J. Clawson, “The Hawaiian Temple,” Millennial Star, 8 January 1920, 32.

[6] “Approved Design for Temple in Alberta Province,” Deseret Semi-Weekly News, 2 January 1913.

[7] Avard Fairbanks, transcripts 3 and 4, in authors’ possession.

[8] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3. Avard again used people from the community as models for this sculpture. Eliza Nāinoa Salm modeled the mother, Manuela Kalili the boy at the mother’s left, Leimomi Kalama Taa the child lying at the mother’s feet, and Mileka Apuakehau Conn the girl kneeling at the mother’s right. Sister Salm recalled that the shell was so heavy it could be supported only for five- or ten-minute intervals. See Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[9] Samuel E. Woolley, in Conference Report, 5–7 October 1917. Samuel Woolley is mainly referring to the promise Lehi made to Joseph, “that the Messiah should be made manifest unto [Joseph’s posterity] in the latter days, in the spirit of power, unto the bringing of them . . . unto light” (2 Nephi 3:4–5). Woolley, as did many others, understood the early arrival of the Church, and now the construction of a temple, as a direct fulfillment of this prophecy among Hawaiians and, more broadly, Polynesians.

[10] For this heroic statute, the elderly Hawaiian Charley Broad, whom Avard deeply respected, posed as Lehi, and Avard’s mentor and good friend Hamana Kalili was pleased to portray Joseph. See Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3; John E. Broad, interview by Clinton Kanahele, Lāʻie, HI, 13 June 1970, Clinton Kanahele Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives; and Clinton Kanahele interviews, vol. 1, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[11] J. Leo Fairbanks, “The Sculpture of the Hawaiian Temple,” Juvenile Instructor, November 1921, 575.

[12] See Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2011), xxii.

[13] William M. Waddoups, “Hawaiian Temple, Laie, Oahu, Hawaii,” Improvement Era, April 1936, 227.

[14] See Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957.

[15] Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence of Hawaiian Temple, 1894–1984, CHL.

[16] William M. Waddoups, journal, 19 January 1920, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Joseph F. C. Rock is considered by many to be the father of Hawaiian botany. Born in Vienna, Austria, in 1884, Rock arrived in Honolulu in 1907 and became the territory’s first botanist. He quickly became an authority on the local flora and was appointed to the University of Hawaiʻi faculty in 1911.

[17] McAllister, Description of the Hawaiian Temple, 8.

[18] Paul L. Anderson, “A Jewel in the Gardens of Paradise: The Art and Architecture of the Hawaiʻi Temple,” BYU Studies 39, no. 4 (2000): 180.

[19] Dedicatory Prayer, Laie Hawaii Temple, 27 November 1919, https://

[20] The first recorded account of the lumber story was a talk given by Romania Hyde Woolley, Ralph Woolley’s wife, on 17 February 1970—over fifty years after construction of the temple. See Marvel Murphy Young, “Finishing the Hawaii Temple,” BYU–Hawaii Archives. The story has since been repeated in a handful of oral histories conducted after her speech. Yet questions about the veracity of this story remain; see James E. Hallstrom to John L. Hepworth, 4 April 1992, Letters Regarding Construction of Laie Hawaii Temple, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[21] Paul L. Anderson explained that the extended time needed to construct the Alberta Temple was due to “the severity of the Canadian winters, the remote location, and the interruption of World War I.” See Paul L. Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples,” Ensign, July 1977.

[22] Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 180.

[23] See R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018), 257–58.

[24] See Britsch, Moramona, 257–59.

[25] Donations were received from the Utah Relief Society Penny Fund and from former missionaries to Hawaiʻi, and the Tongan Mission donated fifty dollars. These contributions were appreciated yet accounted for only a small portion of the total cost of the temple.

[26] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 9 April 1916; and E. L. Miner, “The Hawaii Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 30 May 1916, 778–80.

[27] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 9 April 1916; and Miner, “Hawaii Mission,” 788.

[28] John A. Widtsoe, “The Temple in Hawaii: A Remarkable Fulfilment of Prophecy,” Improvement Era, September 1916, 954. Among these efforts, Viola Kehau Peterson Kawahigashi recalled going with her mother to the villages around Lāʻie “to ask for donations for the building of the temple. Non-members, like the Japanese or the Chinese, would say, ‘. . . we don’t have any money. But we have taro. . . . We would be glad to donate that.’ [A sack of] taro was 100 lbs. for $1.50 in those days.” In Young, “Finishing the Hawaii Temple.”

[29] W. Francis Bailey, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 1–3 August 1973, Salt Lake City, James Moyle Oral History Program, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Bailey added, “We had some very strong faithful Latter-day Saints in the [leper] colony. . . . I don’t suppose there is any place in the world . . . in which there was greater concern for each other and helping each other wherever they possibly could. There seemed to be a distinct brotherhood relationship and it was inspiring.”

[30] See McAllister, Description of the Hawaiian Temple, 10.

[31] Quoted in Dean Clark Ellis and Win Rosa, “‘God Hates a Quitter’: Elder Ford Clark: Diary of Labors in the Hawaiian Mission, 1917–1920 and 1925–1929,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 28, no. 1 (2007): 13.

[32] See McAllister, Description of the Hawaiian Temple, 10, which states, “The Temple and grounds have cost about $215,000.” The Genealogical and Historical Magazine of the Arizona Temple District states, “The actual cost of the Hawaiian Temple as shown from the presiding Bishop’s Office, in Salt Lake City is $256,000.00” (April 1940, 4).

[33] See Jeanne Kuebler, “Sugar Prices and Supplies,” in Editorial Research Reports 2 (1963): 563–82, http://

[34] Hyrum C. Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” Improvement Era, December 1919, 153.

[35] Dorothy L. Behling, “Love for Ohana Helps Bring the Temple,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 9, no. 1 (21 May 1988): 41.

[36] Behling, “Love for Ohana,” 40.

[37] Behling, “Love for Ohana,” 41.