Serving a Growing Membership from the East

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Serving a Growing Membership from the East," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 309–328.

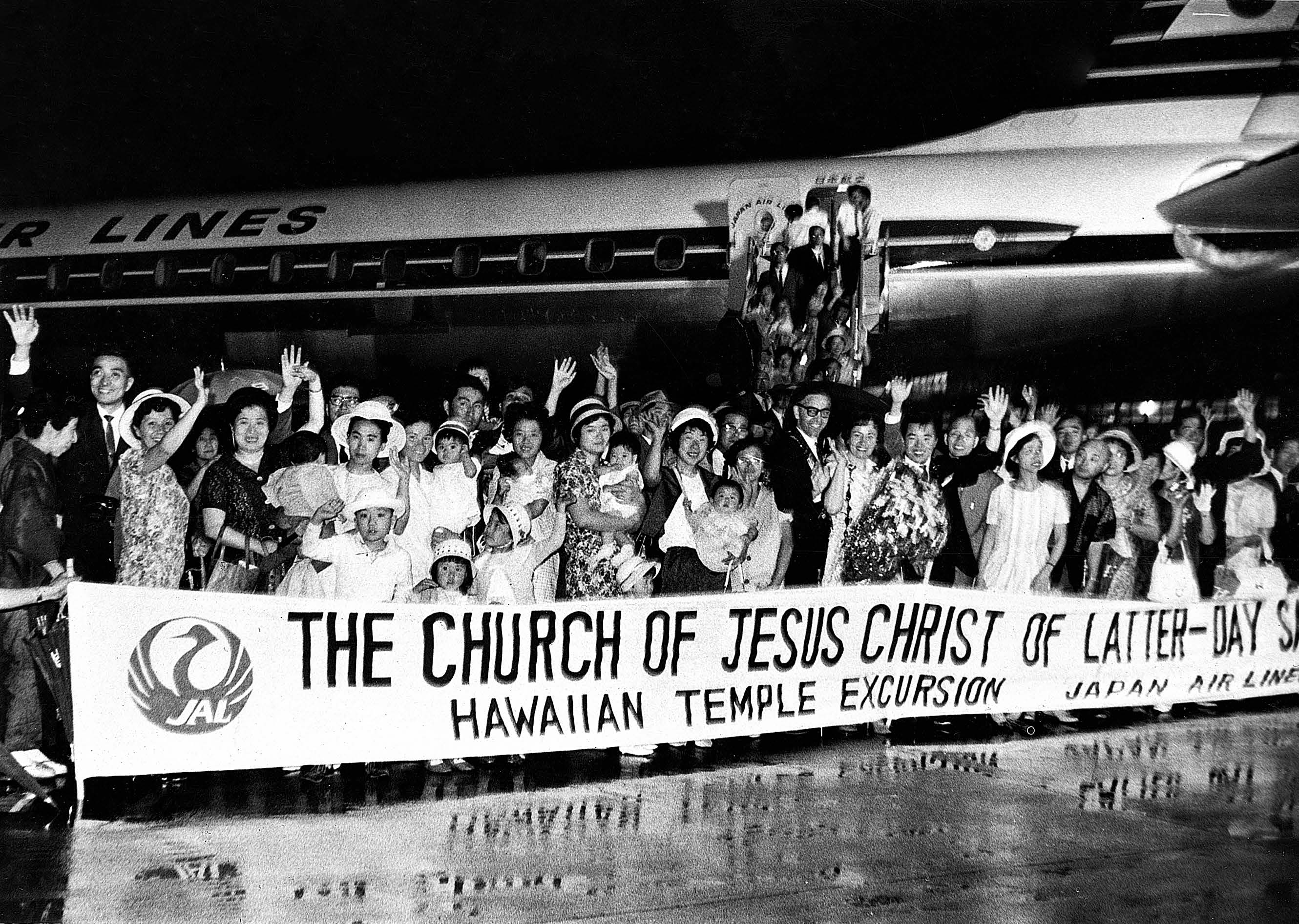

Starting in 1965, Japanese excursions to the Hawaii Temple continued almost yearly through 1979, concluding with the dedication of the Tokyo Temple in 1980. Pictured here is the 1967 Japanese excursion group. Courtesy of Masahisa Watabe and BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Starting in 1965, Japanese excursions to the Hawaii Temple continued almost yearly through 1979, concluding with the dedication of the Tokyo Temple in 1980. Pictured here is the 1967 Japanese excursion group. Courtesy of Masahisa Watabe and BYU–Hawaii Archives.

After World War II the Church began to reestablish itself in Asia and then expand. Until the dedication of the Tokyo Temple in 1980, most of Asia’s Church membership was served by the Hawaii Temple. Although Asian Latter-day Saints had on occasion attended the Hawaii Temple for a number of years, the 1960s and 1970s saw a coordinated and unprecedented effort by these Saints to receive temple blessings in greater numbers.

Japanese Saints Attend the Hawaii Temple

The Japan Mission was established in 1901, but after years of struggle it was closed in 1924. However, among the many soldiers involved in the occupation and reconstruction of Japan[1] at the end of World War II (August 1945) were hundreds of Latter-day Saint servicemen. These young men, most of whom were unable to serve full-time missions owing to the war, were quick to seize the unusual opportunity to share the gospel. In November 1945 Tatsui Sato met some of these Latter-day Saint servicemen, and after careful study he and his wife Chiyo were baptized on 7 July 1946—Tatsui by serviceman C. Elliot Richards and Chiyo by serviceman Boyd K. Packer, who later became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[2]

In his naval assignment Edward L. Clissold also spent time in postwar Japan as part of the occupation, and upon his return to Hawaiʻi he reported to President McKay on the missionary work the servicemen were doing and the possibility of reopening the Japan Mission. Eventually Clissold was called as president of the Japan Mission, arriving in March 1948.[3] He called Tatsui Sato as the mission translator, and over the years Tatsui translated the Book of Mormon, other standard works, books on Church doctrine and history, and numerous tracts, pamphlets, and manuals.[4]

From left: Boyd K. Packer, Norman Nixon, Tatsui Sato, C. Elliott Richards, and Chiyo Sato with son Yasuo. The servicemen helped convert the Sato family, who were some of the first

From left: Boyd K. Packer, Norman Nixon, Tatsui Sato, C. Elliott Richards, and Chiyo Sato with son Yasuo. The servicemen helped convert the Sato family, who were some of the first

people to be baptized in Japan after World War II. Tatsui Sato would later translate the temple ceremony into Japanese. Photo courtesy of Chiyo Nelson Christensen.

Then in the early 1960s, almost fifteen years after the mission reopened, Kenji Yamanaka, a rather influential man in his sixties, joined the Church. Months later, he thought of organizing a group of Japanese members to visit Salt Lake City so they could observe and better understand Church operations. Yamanaka presented this idea to Japan Mission president Dwayne N. Andersen, who then redirected the idea. President Andersen felt strongly that temple attendance by Japanese members would deeply affect their membership.[5] He had served a mission in Hawaiʻi (1941–44), and while serving on Molokaʻi he had helped organize, and had experienced firsthand, one of the inspiring excursions to the temple in Lāʻie. Later, as a young bishop in Concord, California, he prepared a group of unendowed and unsealed families and arranged for them to attend the Los Angeles Temple as a group.[6] Thus strongly desiring that members attend the temple and upon consideration of the expense, President Andersen redirected Yamanaka’s idea into a Japanese member excursion to the Hawaii Temple. Then the two men moved mountains to make it happen.

Financial and spiritual preparation

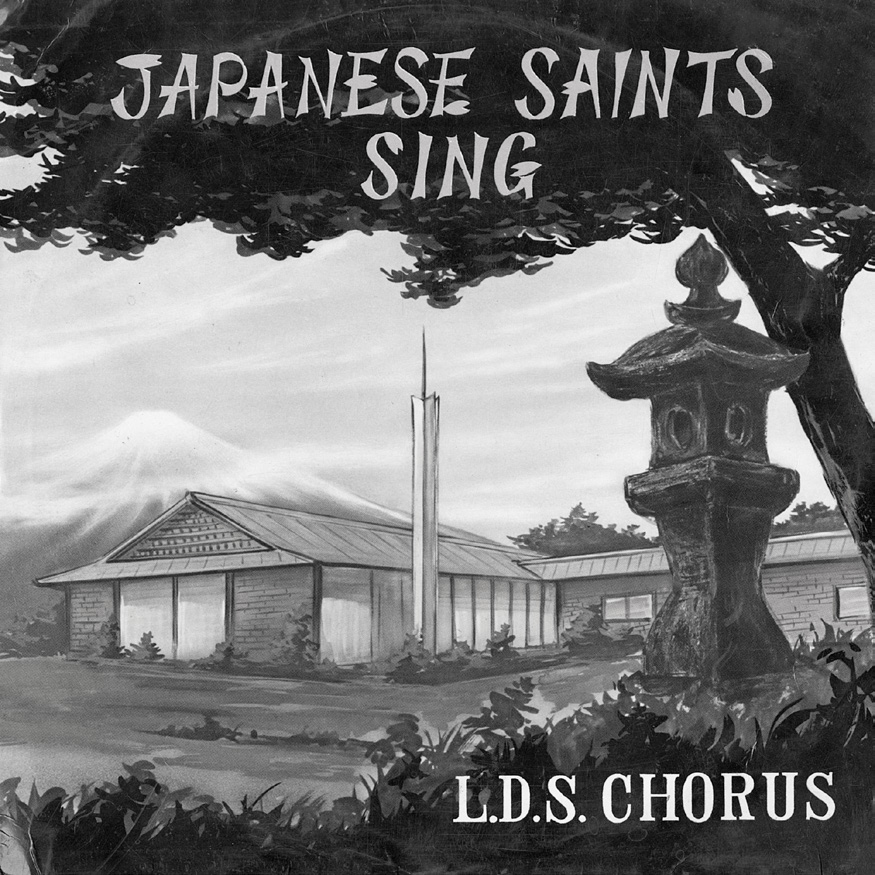

Among the fund-raising projects

Among the fund-raising projects

for the Japanese temple excursion was the stereo recording of a record called Japanese Saints Sing. Photo courtesy of Asia North Area Office. Album cover courtesy of Church History Library.

As Kenji Yamanaka researched the costs, it was discovered that chartering a flight could save over half the cost of airfare, and thus the 165 to 170 seats on such a flight became the target number of members to involve in the excursion. To help offset the enormous cost to members who at that time generally had very little, Yamanaka acquired thousands of pearls, which he and members spent countless hours making into tiepins, single-pearl necklaces, and earrings. These items were given to people who made donations to the temple excursion.[7]

Another fundraising project was the stereo recording of a record called “Japanese Saints Sing.” Yamanaka made arrangements with an orchestra and one of the finest recording studios in Japan to record the songs. Although the twenty-four choir members had practiced for weeks, on the night before the recording, President Andersen noted that “they had not practiced with the orchestra yet and sounded quite poor.” The next day, after a group prayer including the choir, orchestra, and recording personnel, recording began. President Andersen stated: “After recording one song, they played it back so we could hear it. I could not believe my ears! It was just beautiful and sounded like a large chorus. One member told us that they felt like angels were singing with them! It was the first time that an entire record had been taped in one single day. . . . The entire day was just one big miracle. We had many people, after hearing the record, ask us if it was the Tabernacle Choir.”[8]

Successful as these fundraising efforts were, the cost for couples going to the Hawaii Temple was still one-third to one-half their annual salaries—a sacrifice they willingly, and in many cases miraculously, made. To further save money, members made their own temple clothing.[9]

As part of his preparation to translate the temple ceremonies into Japanese, Tatsui Sato (right) arrived in Hawaiʻi months before the Japanese temple excursion and spent weeks in numerous endowment sessions. At left is Tomigoro Takagi, an early Japanese convert. Courtesy of Richard Clissold.

As part of his preparation to translate the temple ceremonies into Japanese, Tatsui Sato (right) arrived in Hawaiʻi months before the Japanese temple excursion and spent weeks in numerous endowment sessions. At left is Tomigoro Takagi, an early Japanese convert. Courtesy of Richard Clissold.

Yet most consequential was the spiritual preparation of the Japanese Saints. All participants were interviewed by a member of the mission presidency at the onset of their preparation, in the middle of their preparation, and just before their departure. The Saints were asked to use family home evening as the time for their spiritual preparation and to read a number of temple-related materials. Most specifically, each member was asked to prepare enough genealogical family group sheets of ancestors to have about eight names cleared in time for temple work in Hawaiʻi. President Andersen noted: “The spiritual and temporal preparations were long and hard; but the rewards were great and wonderful.”[10]

Translation of temple ceremonies into Japanese

Given his assignment over the Asia area of the Church, Apostle Gordon B. Hinckley was well aware of the Japanese Saints’ plan to attend the temple, and during their preparation he spoke to Hawaii Temple president Edward Clissold about arrangements. President Clissold suggested the ceremonies be translated into Japanese and further gave his opinion that “there is only one man” to do the translation, and that was his mission translator and friend Tatsui Sato.[11]

Of all operating temples at that time, the Hawaii Temple seemed ideal for the translation of the ceremonies into Japanese. Not only had President Clissold been a mission president in Japan (1948–49) and president of the Japanese-speaking mission in Hawaiʻi (1942–43), but many local Japanese Saints were available to help with translation, provide the cast of voice characters for the tapes, and work in the temple to assist the Saints from Japan. Furthermore, personnel at the Hawaii Temple were familiar with the process of translating the temple ceremonies, having done so for the Samoan and Māori languages seven years earlier.

Tatsui Sato arrived in Hawaiʻi on 20 January 1965 and attended the temple for his first time two days later. In preparation to translate, “he spent weeks going through countless endowment sessions,” wrote Grace Y. Suzuki, “to imbue himself with the deep significance of man’s elevation to the realm of higher learning.”[12] In March a translation committee headed by President Clissold was organized, with Tatsui Sato, Paul C. Andrus (former president of the Japan Mission), Kichitaro Ikegami, Hideo Kanetsuna, and Grace Suzuki as its members. Initially it was thought to have the committee sit down in the temple together and translate page by page. However, President Clissold felt moved to “place it all in Brother Sato’s hands, let him translate the ceremonies from beginning to end, and then have the translation committee sit down and go over his work.” In the temple from early morning until late at night, over a period of about three months, Sato completed the work. The committee then met in the temple to read the translation page by page and make comments and corrections as it went along. However, as Sato started to read, President Clissold motioned to the others not to interrupt, allowing Sato to read the entire ceremony (almost two hours). “When he was finished, there wasn’t a dry eye around the table,” recalled President Clissold. Those on the committee said, “We have never heard such beautiful Japanese in all our lives. . . . We have never felt the spirit of the temple work as we feel it now in our own native tongue, through the translation of Brother Sato.” President Clissold noted that the translation committee met only twice after that, and he did not recall “more than ten or fifteen changes made in Brother Sato’s translation.”[13]

With the translation complete, cast members were selected for the audio recording.[14] Tatsui Sato, Masugi Uenoyama, Hideo Kanetsuna, Yoshima Akiyama, Sam Shimabukuro, David Ikegami, and Grace Suzuki represented the characters, and Yasuo Niiyama was the narrator. Several rehearsals were held in late May and into June before the arrival of Elder Gordon B. Hinckley with the necessary audio equipment on 22 June 1965. The equipment was set up in the temple that afternoon, and after the cast had practiced for three hours, all agreed to start in the morning.[15] Recording began at 9:00 a.m. and ended at 1:00 p.m., the tape was edited and spliced from 2:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m., and then it was finished.[16] They had accomplished in less than two days what Elder Hinckley said had previously taken weeks to complete.[17]

President David O. McKay authorized President Clissold to call and set apart Japanese members on Oʻahu as temple officiators for the duration of the Japanese excursion. Subsequently, thirteen brethren and nine sisters were trained and set apart on 11 July 1965.[18] Four days later, with the tape complete and workers trained, Japanese members from across Oʻahu attended the first temple session in Japanese on 15 July 1965. Of this session President Clissold wrote: “The workers did very well. . . . It was a historic session. Many of the older Japanese expressed great joy in hearing the ceremonies in their own language.”[19]

Japanese Saints attend the Hawaii Temple

The Japanese Saints landed in Honolulu around 11:00 a.m. on 22 July 1965. “The arrival and reception of our saints in Hawaii was breathtaking,” wrote President Andersen. “Hundreds of people of many nationalities were there with many hundreds of leis. Hawaiian saints placed countless strands of gorgeous flowers around the necks of the Japanese saints—as many as each neck would hold. . . . The love and warmth shown to them by virtual strangers filled the hearts of the Japanese to overflowing.”[20] One of the Japanese brethren later commented: “As I looked out of the airplane and saw Pearl Harbor, and remembered what our country had done to these people on December 7, 1941, I feared in my heart. Will they accept us? But to my surprise they showed greater love and kindness than I had ever seen in my life. Now I have a clearer understanding of Godly love and brotherly love!”[21]

The Japanese Saints landed in Honolulu on 22 July 1965. “The arrival and reception of our saints in Hawaii was breathtaking,” recalled mission president Dwayne Andersen. Courtesy of Masahisa Watabe.

The Japanese Saints landed in Honolulu on 22 July 1965. “The arrival and reception of our saints in Hawaii was breathtaking,” recalled mission president Dwayne Andersen. Courtesy of Masahisa Watabe.

Buses took the Saints to the Church College of Hawaii dormitories, where they would be staying, and that afternoon an instruction meeting was held in the temple visitors’ center auditorium. Because the temple could not hold all the members at once, they were divided into two groups, and on the morning of 23 July the first group entered the temple, with the second group following that afternoon. Of the first day in the temple, President Andersen recorded, “Emotions were high, hearts bursting, and eyes weeping. Neither set of saints wanted to leave the temple after their ordinances were completed. It was only with love and patience that the temple workers could encourage them to depart the premises—telling them that they could again return the next day.”[22] President Wallace Forsythe, counselor in the temple presidency for twenty years, felt assured that this was now the largest number of first-time endowments ever performed in the Hawaii Temple in one day. That night President Clissold ended his journal entry, “15 hours in the temple today and enjoyed every minute.”[23]

The next day, two endowment sessions and opportunities for other ordinance work were available for the Japanese Saints to begin doing the work for their ancestors. That “afternoon brought the sweetest joy imaginable, as children were sealed to their parents.”[24] Adding to this, Elder Gordon B. Hinckley came to participate and thrilled the Saints by performing some of the sealing ordinances.[25] Throughout their stay in Lāʻie, the Japanese Saints were able to participate in five to eight endowment sessions each, as well as perform baptisms, initiatories, and sealing ordinances for their kindred dead.[26]

Along with their spiritual experiences at the temple, there was also a great deal of learning and training. On the first Sunday, the Japanese leaders spent the day with Oʻahu Stake members who held Church callings corresponding to their own, and a special leadership meeting was held so that the Japanese leaders could see how a stake operated. On Monday night the Japanese Saints were invited into various homes in Lāʻie for family home evenings. Some went home teaching with the local members, and a number were able to receive their patriarchal blessings. Yet all was not serious. “The Japanese saints were thrilled with an evening at the Polynesian Cultural Center. They laughed much and heartily clapped as dances and music were presented. They asked: ‘Are all these young people from these different cultures members of OUR church?’ As the answer came in the affirmative, their eyes would light up with excitement. Certainly their minds were being opened up to the expanding of the worldwide Church.”[27]

The 1965 temple group from Japan in front of the Hawaii Temple. “It was an unbelievable ten days!” concluded President Andersen. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The 1965 temple group from Japan in front of the Hawaii Temple. “It was an unbelievable ten days!” concluded President Andersen. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

“It was an unbelievable ten days!” concluded President Andersen. “This marvelous temple experience was more wonderful than we could ever have imagined.”[28] Years later, Andersen noted that among this original group to attend the Hawaii Temple came one General Authority, five regional representatives, five temple presidents (or six if President Andersen is counted, who was the first Tokyo Japan Temple president), six mission presidents, and many other fine Church leaders. Yet likely most impressive was that seventeen years later, 95 percent of these members remained active in the Church.[29]

Japanese excursions to the Hawaii Temple continued almost yearly through 1979, concluding with the dedication of the Tokyo Temple in 1980.[30] What’s more, the success of the Japanese temple excursions that began in 1965 had sparked the possibility of other Saints in the region doing the same.

Korean Temple Excursion

Saints in Korea had long desired to attend the temple, but economic and political conditions presented prohibitive obstacles. Yet despite such constraints, preparations began in January 1970 for an excursion to the Hawaii Temple later that year. Korean Mission president Robert H. Slover and Koo Jung Shik, who had studied law at Seoul National University, worked determinedly to gain government clearance for the temple excursion. Shik recalled, “We received rejections three times from the bureau of International Exchange in applying for approval of our passports. . . . But we didn’t give up. . . . At that time, it was not easy for even high officials to travel abroad as couples.”[31] Reservations had been made for a charter flight to Hawaiʻi with members from Japan in early August, yet less than a month before, clearance had still not been received. “We went up and down the whole scale of government hierarchy,” said President Slover of their efforts to gain approval; it “was almost impossible.”[32] When approval was granted for six couples just two weeks before departure (two individual members would also attend), Shik concluded, “Through the blessings of Heavenly Father, we were able.”[33]

Passports were not the only challenge. Although these Korean Saints had saved at great sacrifice, the economics of the trip remained insurmountable for most of them. However, when a group of former missionaries to Korea (the Korean Missionary Association) learned of the temple trip earlier that year, they began raising funds to help. Regarding the importance of these funds to the fulfillment of this temple trip, President Slover said, “This is the only way they could do it.”[34] And yet another problem, President Slover noted, was that “it appeared that it would not be possible for a translation [of temple ceremonies into Korean] to be completed in time.” However, Spencer J. Palmer, former mission president in Korea, accepted the project and with the help of others was able to readily prepare a tape. President Slover concluded, “To the Korean people the impossible had happened.”[35]

Korean and Japanese Saints in front of the Hawaii Temple in 1970. That year just over a dozen Korean Saints traveled to the Hawaii Temple and connected en route with Japanese Saints making the same trip. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Korean and Japanese Saints in front of the Hawaii Temple in 1970. That year just over a dozen Korean Saints traveled to the Hawaii Temple and connected en route with Japanese Saints making the same trip. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

En route to Hawaiʻi, the six couples flew to Osaka, Japan, where they were warmly welcomed by the Japanese Saints.[36] At that time the 1970 World’s Fair was occurring in Osaka, and the Church had an exhibit therein. Cha Jong Whan, a member of the Korean group, recalled seeing many tourists and even the Japanese emperor. Yet all were eager to board the flight with the Japanese Saints for Hawaiʻi, where several Korean-speaking Church members were awaiting their arrival (returned missionaries, Korean-Hawaiians, and others—some having traveled from the mainland) to assist the Korean Saints and work with them in the temple. Of their arrival Choi Wook Whan said, “The first thing that impressed me in Hawaii was the kindness and open-hearted spirit of the members. They gave us such a wonderful welcome and made everything so pleasant.”[37]

Then on 3 August, the first temple session in Korean was held in the Hawaii Temple. Each member from Korea received the endowment, and the following day all six couples were sealed. In anticipation of the Korean Saints’ arrival, Hawaii Mission president Harry V. Brooks, who acted as sealer, determined to perform all the marriage sealings in the Korean language. Hong Byung-sik, a Korean member from California who assisted, said, “His pronunciation was very good. . . . There was not one word that was not understood. . . . They felt his love and rejoiced at the wonderful blessings they had received.”[38] Of being sealed in the temple Cha Jong Whan said, “We had been married five years earlier, but to be sealed in the temple, on August 4, 1970, was to put my feet on the path of eternal life and bring me one step closer to exaltation.”[39] And of the group’s overall experience attending the temple throughout the week, Choi Wook Whan said, “It opened our minds and awakened to us how we can receive salvation. The eternal plan became real; our testimonies have been strengthened so much it is hard to explain. What a great blessing it is for the people of Korea to have the opportunity of attending the temple.”[40]

Similarly, seven more Korean couples were able to journey to the Hawaii Temple the following year (1971), but very few were able to do so after that.[41] Speaking of those Korean Saints who were able to attend the temple, President Slover noted that they “have made a great deal of difference. . . . They became real spiritual leaders.”[42]

Considering the temple excursions from Japan, Korea, and other islands of the Pacific, the temple’s 1970 annual report recalled the words of President J. Reuben Clark from thirty-five years earlier that Hawaiʻi with its ethnic diversity and temple would be “the outpost of a great forward march for Christianity and the Church, among those mighty peoples that face us along the eastern edge of our sister hemisphere.”[43] The report concluded: “We are living at a time to see this fulfilled, as the Japanese, Korean and others come to have this work done.”[44]

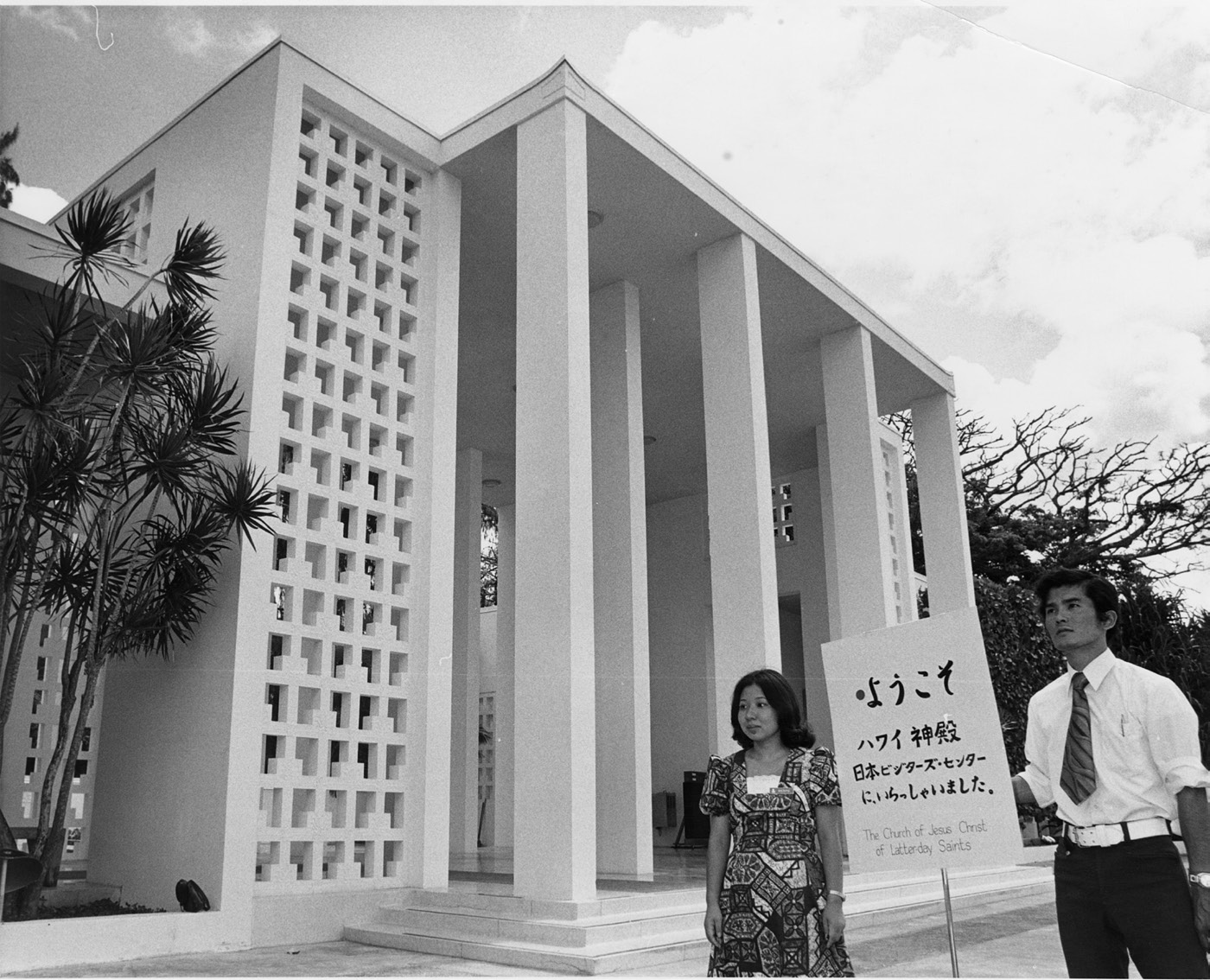

Japanese Visitors’ Center

Perhaps the most noticeable alteration related to the Hawaii Temple in the early 1970s was the installation of the Japanese visitors’ center. More than 320,000 people visited the temple grounds in 1972, and more than 30,000 of them were from Japan. To accommodate Japanese visitors, the building directly across the reflecting pool from the main visitors’ center was renovated in order to house displays in Japanese depicting various facets of the gospel and Church history. Many of these displays had been used in the Church pavilion at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan, and included the movie Man’s Search for Happiness, which was filmed specially in Japan, along with Meet the Mormons and Ancient America Speaks (all in Japanese).[45] Tours of the visitors’ center and temple grounds were offered by Japanese-speaking guides, many of them students at the Church College of Hawaii. Wesley N. Peterson, then director of the Hawaii Temple Visitors’ Center, said, “We’re proud of our beautiful temple, and our new Japanese Visitors Center will explain clearly to our many Japanese guests, who themselves come from a land famous for beautiful shrines and sacred areas, why the Church has built this temple in Hawaii, and why it is sacred.”[46]

Chinese Translation of Temple Ceremonies

In the early 1970s a Japanese visitors’ center was created in the building directly across the reflecting pool from the main visitors’ center. Many of the displays had been used in the Church pavilion at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In the early 1970s a Japanese visitors’ center was created in the building directly across the reflecting pool from the main visitors’ center. Many of the displays had been used in the Church pavilion at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Though never in large excursions, a small number of Saints from Hong Kong came to the Hawaii Temple over the years and were assisted by local members who spoke Chinese.[47] In 1973 the China Hong Kong Mission reported that on 23 June “Hong Kong District President Sheldon Poon, District YMMIA President Andy Ning, Kwok Chiu Au and Wah Ching Kwok left for Hawaii on a special Church assignment. They prepared the tape for the temple endowment service in Cantonese at the Hawaiian Temple.”[48] In 1974 the Hawaii Mission noted: “Temple sessions or preparation for temple sessions are carried out in the following languages in Hawaii: English, Japanese, Korean, Cantonese, Mandarin, Samoan and Tahitian.”[49]

With the proliferation of temples in Asia and the Pacific in the 1980s, the 1970s saw the zenith of international temple excursions to Hawaiʻi. Considering the frequency of these trips, Charles and Lila Walch (president and matron of the Hawaii Temple from 1971 to 1976) marveled: “Members of the Church have come to the temple in groups from Japan, Maui, Molokai, Hawaii, Korea, in addition to many from the mainland and the ever faithful on the island of Oahu. These include those from Samoa, Tonga, Tahiti, Japan, China, New Zealand, Australia, Philippines, and other parts of the world including our faithful ‘haoles.’”[50] From its inception the Hawaii Temple was destined to reach the kindreds, tongues, and peoples of many nations (see Revelation 5:9). And from a historical standpoint, the Hawaii Temple has been among the most ethnically prodigious temples of the latter days.

Notes

[1] After the defeat of Japan in World War II, the United States led the Allies in the occupation and rehabilitation of the Japanese state. Between 1945 and 1952, the US occupying forces, led by General Douglas A. MacArthur, enacted widespread military, political, economic, and social reforms. See “Occupation and Reconstruction of Japan, 1945–52,” United States Department of State, Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, https://

[2] See Terry G. Nelson, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Japan from 1948 to 1980” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1986), https://

[3] See Nelson, “History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Japan,” 11–12.

[4] See “Temple Work Planned in Japanese,” Church News, 17 April 1965, 6.

[5] See Dwayne N. Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography for His Posterity (2001), M270 1 A546d 2001, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), 102–3.

[6] See Nelson, “History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Japan,” 152–56.

[7] See Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 103–4.

[8] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 104.

[9] For an overview of the Japanese Saints’ preparation and the numerous challenges they overcame, see Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 102–11.

[10] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 107.

[11] Edward L. Clissold, “Address,” Japanese Mission Reunion, Salt Lake City, UT, October 1969, MS 15892, CHL. See Clissold, journal, 27 June 1964, in family possession.

[12] Grace Y. Suzuki, “Memories of Brother Tatsui Sato,” in Looking at Heaven and Earth: Memories of Tatsui Sato, ed. Masao Watabe, Kazuo Imai, and Koichi Ishizaka (Japan: n.p., 2004), 126, MS270 1 S253 2004, CHL.

[13] Clissold, “Address,” Japanese Mission Reunion. Clissold added: “I don’t believe there was a man on earth that could have done this work except Brother Sato who has spent eighteen years translating the Book of Mormon, Jesus the Christ, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Articles of Faith. I doubt there are many men in the Church that have the knowledge and understanding of the gospel that Brother Sato has, and I pay tribute to him for his devotion and for his faith and the great ability that he has acquired through his service in the work of the Lord.”

[14] See Clissold, journal, 18 May 1965.

[15] See Clissold, journal, 22 June 1965.

[16] See Clissold, “Address,” Japanese Mission Reunion.

[17] See Edward L. Clissold, interview, 11 February 1980 and 5 April 1982, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, OH-103, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives), 37–38.

[18] President Clissold set apart Frank F. Suzuki, Hideo Kanetsuna, Walter T. Teruya, Allan Barcarse, Kotaro Koizumi, William Nako, Sam Shimabukuro, Yasuo Niiyama, Adney T. Komatsu, Ramon Wasano, Masugi Uenoyama, Kenneth Orton, and Paul G. Andrus. President Wallace G. Forsythe set apart Marion Okawa, Grace Suzuki, Sharon Kanetsuna, Tokoyo Barcarse, Lorriane Abo, Mildred Nako, Judy Komatsu, Florence Orton, and Michiko Shimabukuro.

[19] Clissold, journal, 15 July 1965.

[20] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 109.

[21] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 109.

[22] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 110.

[23] Clissold, journal, 23 July 1965.

[24] As reported in the Northern Far East Mission publication Success Messenger, 15 August 1965.

[25] Departing from the typical one-year waiting period, President David O. McKay gave special permission to four Japanese members to perform temple ordinances for family members who had died less than one year earlier. Elder Gordon B. Hinckley was assigned to work closely with these families. See The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846–2000: A Documentary History, ed. Devery S. Anderson (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), 348; and David O. McKay, diary, 27 April 1965, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

[26] See Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 110.

[27] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 110.

[28] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 111.

[29] Andersen, Dwayne N. Andersen: An Autobiography, 111.

[30] See Adney Komatsu, interview, 8 November 1978, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, OH-56, BYU–Hawaii, 16. Elder Komatsu explained, “In 1965, 1967, and 1969 they had another group, but since 1970 every year they had groups come out to the Hawaii Temple or the Salt Lake Temple.”

[31] Quoted in Spencer J. Palmer and Shirley H. Palmer, eds. and comps., The Korean Saints: Personal Stories of Trial and Triumph, 1950–1980 (Provo, UT: Religious Education, Brigham Young University, 1995), 144–45.

[32] Robert H. Slover, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 16 August 1976, Provo, UT, James Moyle Oral History Program, OH-503, CHL, 20.

[33] Quoted in Palmer and Palmer, Korean Saints, 144–45.

[34] Slover, interview, 16 August 1976, 20.

[35] “Temple Visit Set for 14 Koreans,” Church News, 17 April 1971, 10. See “Saints Find Temple Journey Worth Sacrifice,” The Hawaiian LDS Record-Bulletin, September 1970, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 3.

[36] Korea had emerged from thirty-five years of harsh Japanese rule at the end of World War II, and South Korean diplomatic and trade relations with Japan were not established until 1965. But the warm relationship formed between the Korean and Japanese Saints on this trip once again affirmed that geopolitical differences do not supersede the unifying force of the gospel and these members’ desires for temple blessings.

[37] Choi Wook Whan, “Going to the Temple Is Greatest Blessing,” Church News, 17 April 1971, 10.

[38] “Temple Visit Set for 14 Koreans,” 10.

[39] Quoted in Palmer and Palmer, Korean Saints, 44.

[40] Whan, “Going to the Temple Is Greatest Blessing,” 10.

[41] See R. Lanier Britsch, From the East: History of the Latter-day Saints in Asia, 1851–1996 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 191–92.

[42] Slover, interview, 16 August 1976, 20–21.

[43] J. Reuben Clark Jr., “The Outpost in Mid-Pacific,” Improvement Era, September 1935, 530–35.

[44] Hawaii Temple, annual historical reports, 1970, CHL.

[45] See “Japanese Center Opens,” Ke Alakaʻi, 10 August 1973, 1; and “Japanese Center Dedicated at Hawaii Temple,” Ensign, October 1973, 87.

[46] “Japanese Center Dedicated,” 87.

[47] See Charles Goo, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 18 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 3–4. “I remember helping groups who came from Hong Kong, because of course, at that time they didn’t have any temples in Asia, and my wife and I were assigned to assist in the Cantonese sessions, and ordinances that were performed there. . . . Not very many but there were some Saints that did come. Some went to Utah to be sealed, or receive their endowments, some came here. Just a few families.”

[48] China Hong Kong Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 23 June 1973, CHL.

[49] Frederick T. S. Mau, Hawaii Mission 1974 letter announcing renovation of Hawaii Temple, Frederick T. S. Mau Papers, CHL.

[50] Quoted in Victor L. Walch and David B. Walch, A Worthy Legacy: Memories of Charles Lloyd Walch and Lila Bean Walch (self-published, 2008), 335.