A Major Remodel and Rededication—1970s

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "A Major Remodel and Rededication—1970s," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 329–350.

The 1978 remodel nearly doubled the size of the Hawaii Temple. First Presidency flanked by local leaders at the temple’s rededication, left to right: Glenn Lung, Marion G. Romney, N. Eldon Tanner, Spencer W. Kimball, Adney Komatsu.

The 1978 remodel nearly doubled the size of the Hawaii Temple. First Presidency flanked by local leaders at the temple’s rededication, left to right: Glenn Lung, Marion G. Romney, N. Eldon Tanner, Spencer W. Kimball, Adney Komatsu.

In 1970 only four other functioning Latter-day Saint temples could boast a half century of operation.[1] But with such age came increasing structural needs, and addressing those needs would feature prominently in the temple’s next decade.

New Temple Presidency and Procedures

After nearly nineteen years as prophet and almost fifty years of association with Hawaiʻi and its temple, President David O. McKay passed away in January 1970, and the presidency of Joseph Fielding Smith began. Just over a year later, President Smith called C. Lloyd and Lila B. Walch to be the new president and matron of the Hawaii Temple.

On 5 April 1971, the same day the Walches were set apart for their temple assignment, Church architect Emil Fetzer joined them to present plans for a major remodeling of the Hawaii Temple.[2] However, mostly because of delays in obtaining the necessary government permits, the actual remodeling of the Hawaii Temple would not get underway until June 1976, five years after the Walches first saw the plans.[3] These five years saw a number of changes at the temple.

Return to live sessions

Just over four months into his service, President Walch received a letter from Harold B. Lee, First Counselor in the First Presidency, instructing that there were to be no more audiotape sessions that were not accompanied by slides or a film. Because the Hawaii Temple had never been built or fitted for slide or film presentation of the endowment, this meant a return to live-actor sessions. Without workers prepared to take the live parts (audiotapes had been used for seven years), President Walch phoned President Lee, who permitted use of the tapes for the remainder of the week but said, “Commencing next week, no more taped sessions.”[4] President Walch promptly gathered the temple workers and presented the news. “A wonderful response took place” as the workers accepted the challenge and asked the Lord to help them learn the necessary parts. Literally just days later, all English sessions were conducted live. Of the first live session, President Walch said: “It was done beautifully and almost perfectly. Eyes were filled with tears and hearts were filled with gratitude to our Heavenly Father for helping our wonderful workers to accomplish what had seemed almost impossible.”[5]

Other changes

One month after reinstating live-actor sessions, President Walch noted his surprise at the Saints’ diligence to attend the temple on Thanksgiving, an annual tradition that celebrated the temple’s birthday. He wrote:

It had long been the custom to hold sessions on Thanksgiving morning in commemoration of the dedication of the temple on that day in 1919. On November 25, 1971, our ordinance workers arrived at the temple at 5:00 a.m. . . . To our surprise, there were more than enough [patrons] there to fill our rooms. We commenced sessions immediately and continued every thirty minutes until all who came had an opportunity to fulfill the desire of their hearts, to be in the temple they loved on a day set apart to show our thankfulness for blessings received. There were over 500 endowments performed that morning.[6]

However, this tradition soon ended. President Walch later recorded, “The First Presidency advised us not to continue to hold sessions on this day because it took parents away from their homes on what should be a special family day. This brought to an end the opening of the temple on Thanksgiving.”[7]

In the early ’70s the practice of indexing ordinances inside the temples was discontinued, and the pools in the center of the grounds approaching the temple were reduced in depth and laid with blue glazed tile.[8] Four months after Spencer W. Kimball became President of the Church on 30 December 1973, he and his wife Camilla attended a session in the Hawaii Temple, after which President Kimball spoke to the temple workers directly, offering encouragement and instruction.[9] Also of note, in 1974 the Church College of Hawaii was elevated to the status of university by the Church Board of Education and renamed Brigham Young University–Hawaii.

Remodeling the Temple, 1976–1978

There were various reasons for a major remodeling of the Hawaii Temple in the 1970s. Church membership in Hawaiʻi had nearly tripled since the temple opened in 1919, and this growth was projected to continue. At more than fifty-five years old, the temple was no longer in compliance with building standards and codes. And although extensions, air conditioning, audio technology, and more had been added to the temple throughout the years to meet particular needs, a complete rearrangement of space would considerably increase the temple’s operational efficiency.

Closing the temple

Knowing the temple would soon close spurred a flurry of temple activity. Temple workers determined to forgo the annual summer temple closure so more temple work could be done.[10] Waiʻanae Stake president William Fuhrmann challenged stake members to do one thousand endowments before the temple closed, and a bus was rented for monthly trips to meet this goal.[11] President Walch reported that in the months just prior to the temple’s closing, Church members did the largest volume of work in one month, in one week, and in one day in the temple’s history.[12]

When the temple was closed to ordinance work on 1 June 1976, the office was moved to the temple dormitory (also known as “Temple Court” on Naniloa Loop), furnishings were removed, and temple clothing was stored away. Finally, all set-apart temple workers (the Walches included) were released and the entire building was turned over for construction.[13]

Remodeling the temple

The work began by gutting the annex along the front of the temple and the wings that were added in 1948 and 1962; then several walls were removed. With space around the original temple now more accessible, a large coring machine drilled holes under and around the temple. Extending as deep as forty feet into the subsurface coral, these holes were pumped full of cement to ensure a more secure foundation.[14]

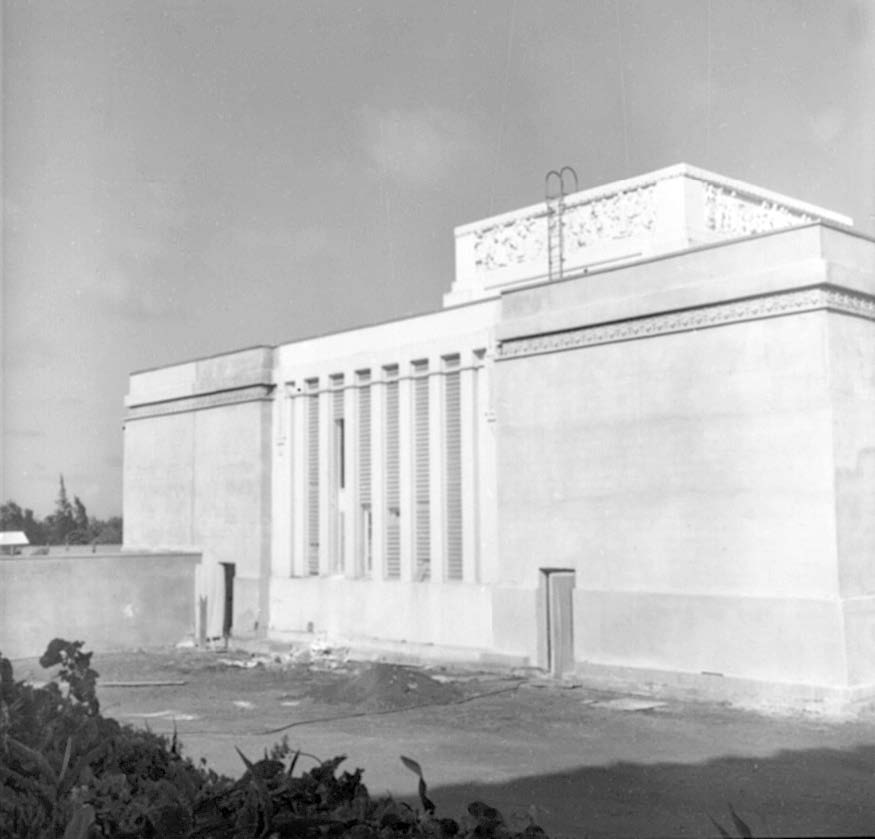

The most noticeable addition was the extension of the main temple entrance about twelve feet forward, doubling the size of the reception area. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The most noticeable addition was the extension of the main temple entrance about twelve feet forward, doubling the size of the reception area. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Approximately twenty thousand square feet were added during the remodel. “We have been able to virtually double the size of the temple,” said Church architect Emil B. Fetzer, “without disturbing the architectural integrity of the original design.”[15] Perhaps the most visible of this additional space was the extension of the main temple entrance about twelve feet forward toward the ocean, nearly doubling the size of the reception area. However, the major additions to the structure were placed in the back so that the temple would retain its traditional appearance from the front and sides.[16]

With the removal of nearly everything but the original core temple structure, and with the addition of so many square feet, the architects were able to efficiently arrange and enlarge the dressing rooms, laundry and dining facilities, clothing issue, workers’ quarters, office space, and instruction rooms. A baptismal chapel with adjacent ordinance rooms and a new entrance to the font area were added on the back of the temple. New areas for initiatory were created, and the four existing sealing rooms were enlarged and two more added. The entire building was air-conditioned and humidity controlled; all electrical, plumbing, and mechanical systems were updated; and all carpeting, draperies, and furnishings were replaced.[17] Amid the remodel, Joseph Tyler, Church building inspector, explained, “We’re doing our best to match the quality of construction that went into the temple in 1918. The techniques have changed radically since that time, but the quality should be equally good.”[18]

Major additions such as a baptismal chapel and ordinance rooms were confined to the back of the temple to preserve its traditional appearance from the front and sides. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Major additions such as a baptismal chapel and ordinance rooms were confined to the back of the temple to preserve its traditional appearance from the front and sides. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

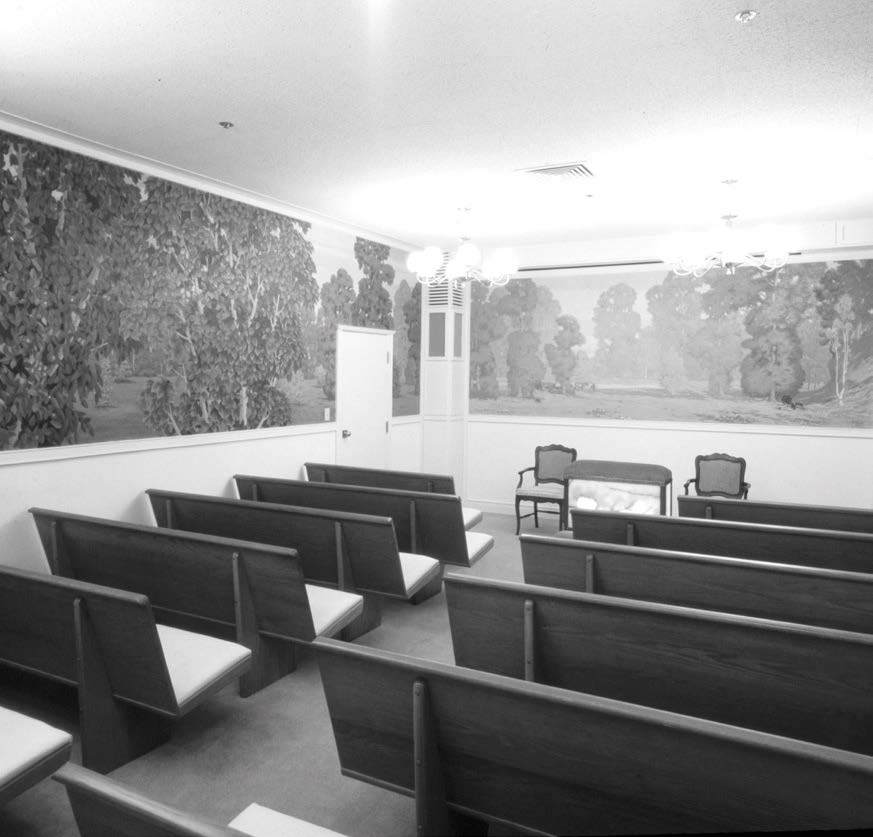

Perhaps most noticeable to a patron’s experience within the temple was that the remodel changed how the endowment was presented. “The progressive-style ordinance rooms featuring a live presentation of . . . the endowment were converted to stationary rooms in which the film version of the endowment was used. This required an audio-visual projection system to be installed in the temple’s ordinance rooms.”[19] Lost was the progressive nature of starting in the creation room, moving through the rooms representing the stages of life, and finally ending in the celestial room. However, function over form allowed for much greater capacity (a major reason for the remodel) and better accommodated those unable to climb the stairs throughout the temple.

An opportunity to clean the temple

Lila Waite, Lāʻie Stake Relief Society president, was asked to coordinate the temple cleaning before its opening. At that time married members were unable to be endowed without their spouse, and Sister Waite specifically asked the various stake Relief Society presidencies on Oʻahu to “call women who had not the opportunity to go to the temple, but were worthy in every way.” Sister Waite recalled:

After we finished cleaning each day at 3 o’clock, we would take the women on tours throughout the temple, and we would say to them, “You can open any door that you want to; you can ask any question, and we will try to do our best in answering them.” We wanted them to know that there were no secrets . . . that it was a beautiful and sacred place. We wanted them to become familiar with it. . . . Their faces would light up; they would be so thrilled to see each room and they would want to know the purpose of each room. They especially loved the Baptismal Font, the Sealing Rooms, and the Celestial Room. One of the sisters said when we walked into the Celestial Room, “I have given up on that dream a long time ago, but now I have it back again.”[20]

Open house

With the temple remodel, patrons would no longer move progressively through the creation, garden, and world rooms for a live endowment session. Instead, each of the three rooms could now feature a full film presentation of the endowment, serving more patrons, a major reason for the remodel. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

With the temple remodel, patrons would no longer move progressively through the creation, garden, and world rooms for a live endowment session. Instead, each of the three rooms could now feature a full film presentation of the endowment, serving more patrons, a major reason for the remodel. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Just over a year into the remodel, the First Presidency announced the appointment of Max W. and Muriel P. Moody as the new president and matron of the Hawaii Temple. Max had been president of the Honolulu Stake, and he and Muriel had been temple workers for a number of years. Although the temple would not be rededicated for another nine months, the Moodys would play an invaluable role in getting the temple ready to function upon reopening, and they assisted with the temple open house and rededication.[21]

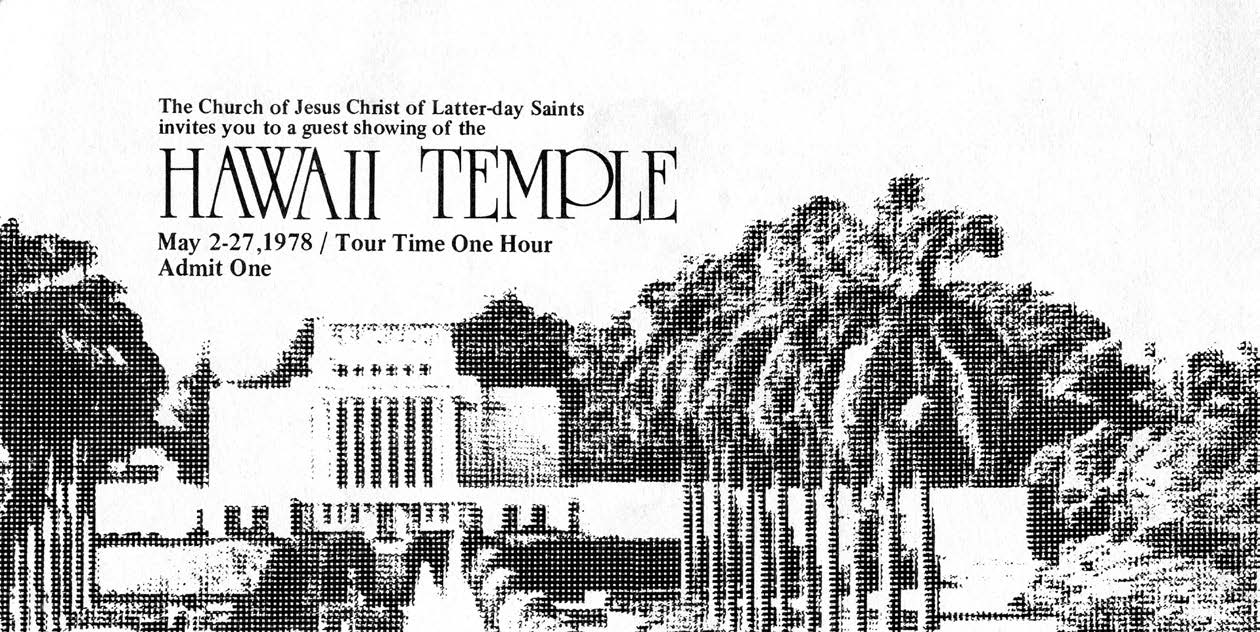

In 1978 the First Presidency announced that the Hawaii Temple would conduct an open house from 2 to 27 May. This was the first time since its dedication in 1919 that the temple would be open to the public, and President Moody encouraged members to invite less-active family members and friends, as well as friends of other faiths, to the open house.[22] “The goal of the Open House isn’t to satisfy curiosity,” said President Moody. “It’s to educate people who want more out of life than they’re getting now.”[23]

Elder Howard W. Hunter, then an Apostle, led a special preview showing of the newly remodeled temple to Hawaiʻi business, civic, government and religious leaders on 1 May.[24] Volunteer guides from every stake on Oʻahu ushered visitors through the temple in the weeks that followed. Sunset, a travel magazine, explained that “guided tours lasting half an hour will take you through the main section of the building. . . . Viewing will include the baptismal font area; the sealing rooms, where eternal marriages are performed; and ordinance rooms, with murals symbolically depicting man’s journey through life.”[25] A final tally showed that 110,805 people went through the temple during the open house. About 80 percent of visitors (88,644) were not members, and more than 55,000 of them asked for further information on the Church.[26]

Among these visitors was Paula Faufata, who, while out with friends in May 1978 and hearing that the temple was open, attended the tour. She recalled that as she made her way up the final flight of stairs and entered the doorway, “something warm, sweet and beautiful came over me, and I began to cry uncontrollably. I asked the girl [attendant], ‘Where are we,’ and she responded, ‘the celestial room.’ I told my friends, ‘I will come back soon and in the right way.’”[27] Paula was baptized and would spend decades doing family history and temple work. Also among the visitors was a nonmember teacher at Kūhiō Elementary School in Honolulu who impressed her students so much about the sanctity of the temple that some of them bought new shoes before their visit (many of Hawaiʻi’s schoolchildren only owned sandals).[28]

Ticket for the 1978 open house, the first since the temple’s dedication in 1919. More than

Ticket for the 1978 open house, the first since the temple’s dedication in 1919. More than

110,000 people attended the 1978 event, approximately 80 percent of whom were not members. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Church members also benefited from the temple open house. Kim Phillips, a BYU–Hawaii student and recent convert, said the open house was “the first time I had been inside an LDS temple. I too was struck with a feeling of warmth and love as I entered the building. I gained a greater understanding of Church doctrine and a renewed sense of the importance of temple marriage, baptism for the dead, and other ordinances just by walking though the sacred edifice. I determined to work on my genealogy.”[29]

Rededication of the temple

From 13 to 15 June 1978, nine dedicatory sessions were held (at 9:30 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 4:30 p.m. each day) to accommodate the nearly nine thousand members who attended. Each session originated from the celestial room of the temple, which seated approximately 120 people. Others viewed the proceedings on closed-circuit television in other rooms of the temple and in designated rooms at BYU–Hawaii.[30]

In addition to President Spencer W. Kimball, other General Authorities participating in the dedicatory services were Presidents N. Eldon Tanner and Marion G. Romney of the First Presidency; President Ezra Taft Benson and Elders Howard W. Hunter and Marvin J. Ashton of the Quorum of the Twelve; and Elders Marion D. Hanks, O. Leslie Stone, Adney Y. Komatsu, and John H. Groberg of the First Quorum of the Seventy.[31]

The dedicatory prayer was repeated in each session and began with deep gratitude for Jesus Christ, the restored gospel, and Church leadership past and present. It petitioned for “all nations, that their hearts may be inclined toward [God].” Appreciation was given for the rich heritage of the gospel in Hawaiʻi and the Pacific.[32]

Then, specific to its purpose, the prayer stated: “We rededicate to Thee the grounds and the building with all the furnishings and fittings and everything pertaining thereunto, from the foundation to the roof thereof, to Thee, our Father, God. . . . May all who come upon these grounds, whether members of the Church or not, feel the sweet and peaceful influence of this blessed, hallowed spot.” Of the work beyond the temple walls, it was asked that the way be opened for “the members of the Church in these lands as well as other islands, to secure the genealogies of their forefathers so that they may come to this holy house and become saviors unto their ancestors.”[33]

In closing, the prayer particularly petitioned blessings on the island natives—“that they may long live upon this land, to further Thy cause”—and on the youth: “Shield and preserve and protect them from the adversary. . . . Preserve them in purity and in truth.” Then, in benefit of all who enter the temple, the prayer concluded, “We most earnestly pray that this sacred building may be a place in which Thou shalt delight to pour out Thy Holy Spirit in great abundance and in which Thy Son may see fit to manifest Himself and to instruct.”[34]

Speakers’ remarks

Among his remarks shared during the rededication, President Kimball called for a “reformation in the homes of every Latter-day Saint. Let us begin with our children so they’ll be prepared and when they’re married they’ll think of just one place, and this is the temple.” President Kimball then suggested that a picture of one of the temples be placed in the bedroom of each child and asked that the parents use family home evening to teach their children about eternal marriage.[35] Sister Camilla Kimball also spoke, expressing that one of the greatest blessings of the temple to her was the assurance of being with our loved ones again and that frequent visits to the temple offered time for contemplation.

In his remarks, President Benson noted that the Hawaii Temple had a special place in the hearts of his family. His wife, Flora Amussen Benson, served a mission in the Hawaiian Islands, and for a time she taught in the Church school in Lāʻie during the day and worked in the temple in the evening. President Benson shared that one evening after officiating and straightening things in the temple, Flora discovered that all the others had gone home and she was alone. It was dark outside and she was concerned. She prayed to the Lord that she would be protected, and as she left the temple door, a circle of light surrounded her and moved with her until she entered the mission home door. She always felt, as did her family whenever she shared this experience, that this was an answer to prayer.[36]

President Benson encouraged stake and ward temple days and then counseled, “Let’s go to the temple often, at least once each month. Let’s . . . have our children note the joy with which we prepare to go to the temple. Rich blessings, answers to prayers, will come as we ponder the eternal verities and let our minds rest upon the solemnities of eternity in the temple of God—the nearest place to heaven on mortal earth.”[37]

Elder Howard W. Hunter shared that when the Hawaii Temple was dedicated in 1919 there were fewer than half a million members in the Church and that a total of 78,000 endowments had been performed in the four temples in Utah. Further, in 1977 3,600,000 endowments had been performed in all the temples and membership had climbed to four million. He then noted that from 1919 to 1977, Church membership had increased eight times while the number of endowments had increased fifty times. With the increased capacity of the Hawaii Temple and further plans underway to expand temple work throughout the world, he expected that number would grow many, many more times.[38]

Elder Marvin J. Ashton had long been associated with Lāʻie through his leadership on the BYU–Hawaii and Polynesian Cultural Center boards. He knew the synergistic relationship between the temple, university, and PCC, and like many others, he understood the loss to this dynamic during the temple’s two-year closure. Ashton noted that he had hoped and prayed for the day when unitedly the temple, university, and PCC could again go forward as one and build the kingdom. As the temple was rededicated that day, he felt his prayers were answered. He then taught, “The temple is not a destination, but a starting point.”[39]

Elder Adney Y. Komatsu reminded those present that beyond the blessings of personally receiving the sacred ordinances and extending those blessings to those beyond the veil, temple attendance provides useful instruction in gospel principles. In addition, the temple is a place of meditation and worship, a place for contemplation and prayer, a sanctuary from the world—a bit of heaven on earth. As a result of continued temple activity, he added, people are more aware of the world in which they live, more dedicated to the purposes of God, and better equipped to deal with and overcome the trials and temptations of life. He concluded that for these reasons, and many others, we are encouraged to return to the temple frequently and regularly.

“Tūtū” Colburn

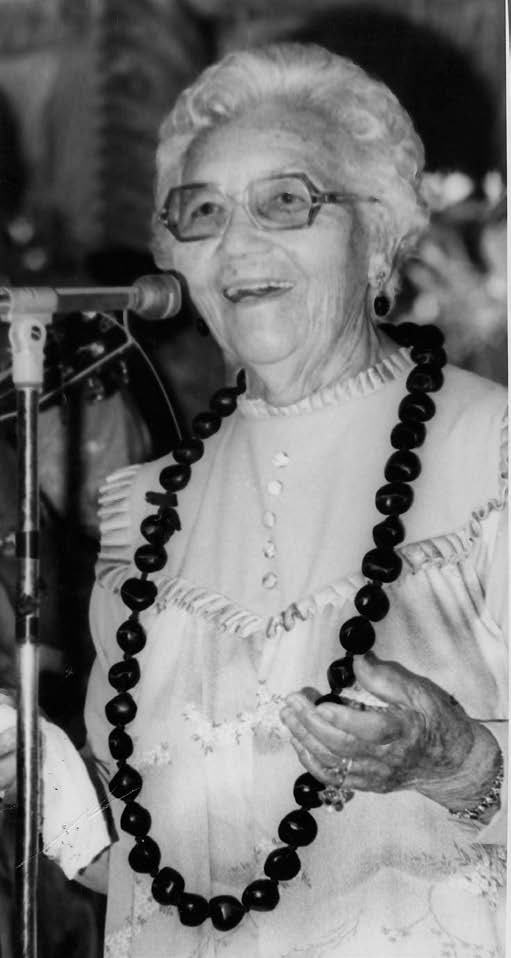

When Lydia Kahōkūhealani Colburn was a young mother, her two-week-old son died. “In my former church he had no chance for salvation because he had not been baptized,” she said. “I did not think that was right.” The restored gospel, with its doctrine of temple work for the dead, felt right to her, and she was baptized in 1907. When the Hawaii Temple was dedicated in 1919, thirty-two-year-old Sister Colburn sang soprano in the choir at the dedicatory service. Nearly fifty-nine years later, at age ninety-one, she sang in the choir at the 1978 rededication, giving her the distinction of being the only person to sing at both dedications of the temple. She passed away five months after singing at the temple rededication.[40]

Temple Blessings for All

Nearly 59 years after singing at

Nearly 59 years after singing at

the 1919 temple dedication, Lydia Kahokuhealani Colburn felt blessed to sing at the 1978 rededication as well. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In the ninth and final rededicatory session of the Hawaii Temple, President Kimball read a letter released just six days earlier by the First Presidency that was reverberating in the press. The letter has since become known as Official Declaration 2 in the Doctrine and Covenants, and it rescinded a policy in place since 1852 that members of African descent could not hold the priesthood or receive temple ordinances.[41] After reading the letter to those in the final session, President Kimball affirmed its direction from the Lord and expressed his deep hope that many lives would be blessed as a result.[42]

Among those in Hawaiʻi who were blessed by this revelation were Ilene Marrotte and her family. After marrying a Church member, Ilene was baptized in 1968. Her bishop invited her and her husband to prepare to go to the temple, and it was then that her husband told her of the Church’s policy. One of Ilene’s grandparents had African heritage. Yet her bishop, Kotaro Koizumi, made her a promise: “As sure as the sun will rise in the morning, Heavenly Father will someday have your family sealed in the temple for time and all eternity.” Ilene held on to this promise and supported her husband as he went to the temple every Saturday. However, Ilene found it difficult not to have the promises of the temple, especially when her infant daughter died in 1970.

The Marrotte family was elated to hear news of the 1978 revelation. Two days after the letter was released, President Kimball attended a stake conference in Kauaʻi where the Marrottes lived. After the conference, the family briefly met the prophet and shook his hand. Not long after, they traveled to Lāʻie. Ilene recalled, “We went to the temple on August 5, 1978, to seal our family for time and all eternity. As we knelt in the sealing room, tears of joy filled our hearts, seeing my children dressed in white. Our Bishop[’s] wife was proxy for our daughter who had passed away.”[43]

All-Night Temple Sessions

Ilene Marrotte and her family

Ilene Marrotte and her family

were among those in Hawaiʻi

who were blessed by the 1978

revelation extending temple

blessings to all. Ilene briefly met

President Spencer W. Kimball

two days after the announcement, and shortly thereafter her family was sealed in the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Temple work resumed after the rededication, and so did an old challenge. For many years it was procedure for Church headquarters in Salt Lake to send temple-ready groups of names (often called a “batch”) to individual temples, and when the temple work for that batch was complete, another batch would be sent. The challenge this presented was that baptism, confirmation, and initiatory could be done rather quickly, but names, particularly male names, could be held up for several months until the endowments were completed.[44]

In part to address this challenge, the scheduling of special “priesthood sessions” in the temple had been almost standard since the 1950s. This practice continued under President Moody, with priesthood sessions held on the first two Saturdays of each month, a Samoan priesthood session on Thursdays, and a PCC priesthood session on Wednesdays.[45] However, despite these efforts, thousands of male names backed up, awaiting endowments.

Considering this imbalance and President Kimball’s statement that he looked forward to a time “when the temples will be used around the clock,”[46] Bishop Herbert K. Kahikina of the Kaimukī Ward proposed that his priesthood holders arrange a special all-night session to help equalize the imbalance between male and female endowments. Permission was granted, and in 1979 eight sessions were held from 7:30 p.m. on 18 May to 7:30 a.m. on 19 May. Three hundred and fifty men plus a group of women (“admittedly a little drowsy”) participated that night, completing 865 endowments.[47] Other wards and stakes followed. A total of five all-night priesthood sessions were held in 1979. As a result, the imbalance of male to female names was decreased from approximately 4,000 to 301. The practice of all-night sessions was discontinued the following year in favor of providing more priesthood sessions on Saturdays.[48]

All-night temple sessions were introduced in the Hawaii Temple in 1979. Though discontinued the following year, the practice nearly eliminated the backlog of male names awaiting ordinance work at that time. Photo by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

All-night temple sessions were introduced in the Hawaii Temple in 1979. Though discontinued the following year, the practice nearly eliminated the backlog of male names awaiting ordinance work at that time. Photo by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Coincidentally, these all-night sessions coincided with the global oil crisis in 1979.[49] In an effort to conserve energy, policy dictated that lights outside the temple and on the grounds be limited to those necessary for security.[50] Exceptions to this policy were only made for special occasions such as these all-night temple sessions.

Tahitian and Japanese Excursions in 1979

Since 1958, Tahitian Saints had generally attended the New Zealand Temple, but they occasionally visited the Hawaii Temple. In 1979 twenty-five members from two wards in Tahiti traveled to the Hawaii Temple for three weeks. Within this group, nine families were sealed, including Marc Georges and his wife Henrietta, who was pregnant. Upon their return to Tahiti, a baby boy was born, and his father said, “In his (the baby’s) room we have hung a picture of the Hawaiian Temple to remind him that his parents have been sealed there and that he can, one day, enter the Holy House of our Father in Heaven.”[51] Because the Tokyo Temple would be dedicated the following year, that summer saw the last official temple excursion from Japan to the Hawaii Temple. Such excursions from Japan had occurred nearly yearly for fifteen years.[52]

End of an Era

For almost forty years (1919–58), the Hawaii Temple stood alone in its service to members in the Pacific and Asia. It then divided that geographic responsibility with the New Zealand Temple for just over twenty years (1959–80). However, the advent of the Tokyo Temple in 1980 was the beginning of an increase of temples in the region. Temples were dedicated in Samoa, Tonga, and Tahiti in 1983, in the Philippines and Taiwan in 1984, and in Korea in 1985. But the Hawaii Temple’s reach into these areas has not entirely ended, for BYU–Hawaii has continued to draw students from across the Pacific and Asia, many of whom return home spiritually fortified and with a lifelong love for temple work forged within the walls of the Hawaii Temple.

The reduced geographic reach of the Hawaii Temple coincided with new opportunities. Signaling the potential use of computers in temple work, a 1979 article on the growing uses of computers in Hawaiʻi noted the use of a minicomputer at ʻIolani Palace (the former residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi) as well as at the temple at Lāʻie.[53] Burgeoning missionary work in Micronesia would see the Hawaii Temple once again providing blessings for members from across large areas of the Pacific. And as membership in Hawaiʻi continued to grow, the newly renovated temple offered greater capacity, efficiency, and flexibility of scheduling. Though its geographic reach would recede, the future of the Hawaii Temple remained bright.

Notes

[1] That is, the St. George, Logan, Manti, and Salt Lake Temples. From the commencement of temple work in 1841 to the end of 1970, the combined work in all temples had arrived at 35,683,789 baptisms and 33,220,205 endowments. The Hawaii Temple’s 32,332 endowments in 1970 helped raise that year’s worldwide total to 1,667,923. See “Temple Endowment on Way Up, President Brooks Says,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, June 1971, 1.

[2] See Victor L. Walch and David B. Walch, A Worthy Legacy: Memories of Charles Lloyd Walch and Lila Bean Walch, MSSH 321, 332, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[3] See Walch, Worthy Legacy, 333.

[4] Walch, Worthy Legacy, 333–34.

[5] Walch, Worthy Legacy, 333–34. Although all English sessions returned to live actors, use of audiotapes for foreign languages continued.

[6] Walch, Worthy Legacy, 333.

[7] Walch, Worthy Legacy, 333.

[8] See Yearly Temple Reports, 1972, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[9] See Yearly Temple Reports, 1974, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[10] See Yearly Temple Reports, 1975, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[11] See Theodore W. H. Maeda, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 18 March 2017, CHL.

[12] See “Every Day in Temple Has Been a Highlight,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, Summer 1976, 2.

[13] See Yearly Temple Reports, 1976, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[14] See “Reconstruction Underway,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, September 1976, 9.

[15] Don L. LeFevre, “Thousands Tour Hawaii Temple,” Church News, 6 May 1978, 3.

[16] See “Reconstruction Underway,” 9; and LeFevre, “Thousands Tour Hawaii Temple,” 3.

[17] See LeFevre, “Thousands Tour Hawaii Temple,” 3; “An Architect’s View of the Mormon Temple at Laie,” Hawaii Architect, May 1978, 18–19; and “Reconstruction Underway,” 9.

[18] “Reconstruction Underway,” 9.

[19] Chad M. Orton, “Laie Hawaii Temple” (manuscript, 2017), in private possession.

[20] Lila Waite, interview, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, OH-395, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 8–9.

[21] See “Moody Called to Head Hawaiian Temple,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, October–November 1977, 16.

[22] See “Temple Reopens: Will Be Re-Dedicated By Prophet on June 13,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, March 1978, 3.

[23] “Public Take Opportunity to See Famed LDS Temple; They Like What They See,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, June 1978, 12–13.

[24] See “Hawaii Temple Will Open for Special Tours,” Church News, 29 April 1978, 3.

[25] “Rare Opening of Oahu’s Temple,” Sunset: The Magazine of Western Living, May 1978.

[26] See “Public Take Opportunity,” 12–13. See also Michael Foley, “Multitudes Visit Hawaii Temple: Thousands of Non-LDS Anxious to Know More,” Church News, 17 June 1978, 7.

[27] Paula Faufata, reminiscence, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[28] See Foley, “Multitudes Visit Hawaii Temple,” 7.

[29] “Testimony Strengthened by Non-Members,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, June 1978, 11.

[30] See Dell Van Orden, “Remodeled Temple Is Rededicated in Laie,” Church News, 24 June 1978, 3–4. See also Alf Pratte, “Hawaii Temple Rededicated,” Ensign, August 1978, 77.

[31] See Van Orden, “Remodeled Temple Is Rededicated,” 3–4.

[32] “Dedicatory Prayer, Laie Hawaii Temple, 13 June 1978,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://

[33] “Dedicatory Prayer.”

[34] “Dedicatory Prayer.”

[35] Van Orden, “Remodeled Temple Is Rededicated,” 3–4. See Pratte, “Hawaii Temple Rededicated,” 77.

[36] See Derin Head Rodriguez, “Flora Amussen Benson: Handmaiden of the Lord, Helpmeet of a Prophet, Mother in Zion,” Ensign, March 1987. See also chap. 6 in Sheri L. Dew, Ezra Taft Benson: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1987).

[37] Van Orden, “Remodeled Temple Is Rededicated,” 3–4.

[38] See Van Orden, “Remodeled Temple Is Rededicated,” 3–4. See also Pratte, “Hawaii Temple Rededicated,” 77.

[39] Van Orden, “Remodeled Temple Is Rededicated,” 3–4.

[40] See Dell Van Orden, “She’s Almost 91, ‘Tu Tu’ Colburn Continues to Sing,” Church News, 24 June 1978, 4.

[41] See “Race and the Priesthood,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://

[42] The letter, dated Thursday, 8 June 1978, was made public the following day, and two days later “President Kimball visited the island of Kauai June 11 [Sunday], meeting with representatives of the news media in a news conference and interviews. He then presided at nine Hawaii Temple rededication services June 13 through 15.” Alf Pratte, “The Time to ‘Do It’ Is Now, Pleads President Kimball at Hawaii Area Conference,” Ensign, August 1978, 74.

[43] See Ilene Marrotte, Ilene Marrotte Story, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[44] See Wayne Yoshimura, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 16 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[45] See “Women Far Ahead of Men in Temple Attendance, Work,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, May 1979, 2.

[46] Spencer W. Kimball, “Greater Need Brings Temple’s Renovation,” Church News, 19 April 1975, 3.

[47] “Temple ‘All-Nighter’ Brings out the Best in People,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, June 1979, 3.

[48] See “Temple Drops Night Session,” Hawaii Record Bulletin, January 1980, 6. As effective as the all-night sessions may have been, Wayne Yoshimura recalled, “We went through the numbers, but the spirituality part, I think, was lacking. I recognized a lot of people going in there and sleeping, snoring, it took away from the spirit.” Yoshimura, interview.

[49] Because of decreased oil output in the Middle East, the price of crude oil more than doubled, resulting in long lines at gas stations.

[50] See Yearly Temple Reports, 1979, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[51] “Temple Busy for Tahitians,” Ke Alakaʻi, 31 August 1979, 14.

[52] See “200 Japanese Saints Pass through Hawaii Temple,” Ke Alakaʻi, 31 August 1979, 15.

[53] See Dorothy Gannon, Pacific Business News, 1979.