To Kindreds, Tongues, Peoples, and Nations

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "To Kindreds, Tongues, Peoples, and Nations," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 183–204.

New Zealand Saints attending the Hawaii Temple in 1926. Other than a decade-gap surrounding World War II, such temple trips occurred every couple of years from 1920 until the dedication of the New Zealand Temple in 1958. Courtesy of Hyran Smith.

New Zealand Saints attending the Hawaii Temple in 1926. Other than a decade-gap surrounding World War II, such temple trips occurred every couple of years from 1920 until the dedication of the New Zealand Temple in 1958. Courtesy of Hyran Smith.

From the beginning, the foundation for the work in the Hawaii Temple was made possible thanks to the consistent and rather unnoticed service of local members. Elder members of Lāʻie and the surrounding community were able and eager to make temple service a regular part of their lives.[1] Other members, too, pitched in—like Eliza Leialoha Nainoa Salm, who weekly prepared a box lunch and readied the temple bags so that when her husband Frederick got home, they and their young daughter Flora could make the drive to attend the temple.[2] Or George Mahi, who after moving from Maui to Oʻahu determined to help gather names and do the work for families from the outer islands who were unable to make the trip themselves.[3] It was the seemingly common yet consistent efforts of Saints like these that, when combined, became the steady strength behind the temple’s success.

However, from its inception the Hawaii Temple was destined to reach many kindreds, tongues, peoples, and nations (see Revelation 5:9). From a historical standpoint, it has been among the most ethnically prodigious temples of the latter days, and it began earning this moniker within months of its dedication with the arrival of Māori Saints.

Māori Saints

The 1920 Māori temple group, who brought lengthy Māori genealogies for temple work, sparked tremendous public interest in the possibility of shared ancestry between the Hawaiian and Māori peoples. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The 1920 Māori temple group, who brought lengthy Māori genealogies for temple work, sparked tremendous public interest in the possibility of shared ancestry between the Hawaiian and Māori peoples. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In his announcement of the Hawaii Temple in 1915, President Joseph F. Smith was clear that this temple would serve members throughout the Pacific region.[4] Thus many Saints in New Zealand were keenly interested in the progress of the temple, and mission president James N. Lambert intended to escort a party of Māori Saints (natives of New Zealand) to the dedication services.[5] In preparation for this event, President Lambert negotiated with the government for permission for these members to attend. He even assigned a sister missionary to organize sewing bees with the Māori women who had been endowed in the Salt Lake Temple to make ten sets of temple clothing for the anticipated visit.[6]

Yet because of the rather sudden scheduling of the temple’s dedication in November 1919, no Church members from New Zealand were able to attend the dedication. Aware of this unfortunate circumstance, President Heber J. Grant advised President Lambert to accompany the Māori Saints to the temple after the mission conference in April.[7] Ultimately fourteen Māori Saints[8] traveled to Hawaiʻi with President Lambert and his family. Arriving in Honolulu on 16 May 1920 to a warm reception, they would stay for ten weeks.[9]

As they would do countless times for temple visitors in the years to come, members in Lāʻie opened their doors to the Māori Saints. Local members would often gather with the visitors at the Broad[10] family home and spend the evening in song and entertainment.[11] Such arranged and spontaneous gatherings would occur throughout the Māori Saints’ stay and included cottage testimony meetings as well.[12]

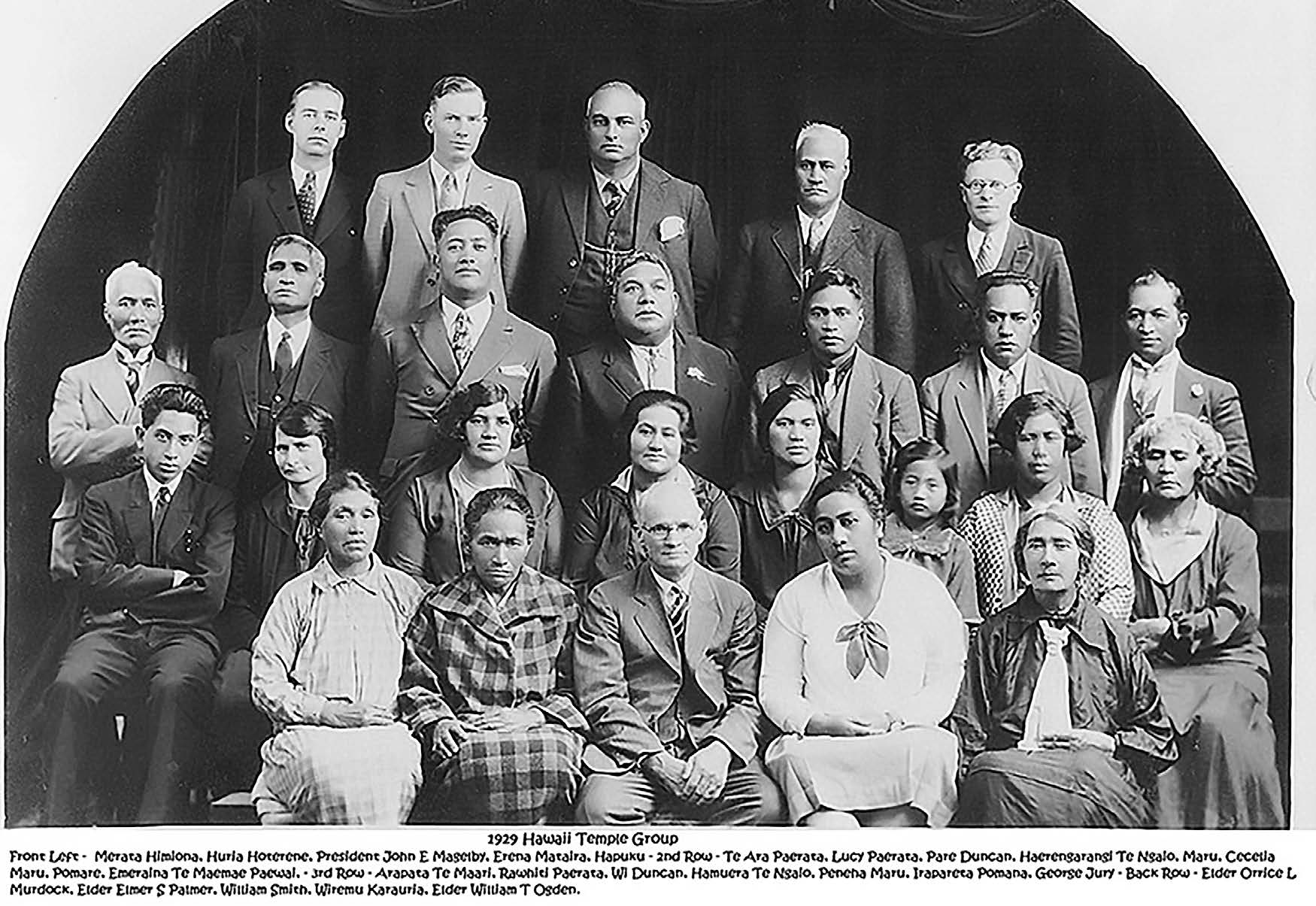

1929 Māori temple group. Despite numerous hindrances, this group persisted and was finally able to journey to the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Hyran Smith.

1929 Māori temple group. Despite numerous hindrances, this group persisted and was finally able to journey to the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Hyran Smith.

“It was a real thrill,” wrote Elder Patrick L. Carroll, a temple worker, “to feel their spirit and see their joy at being able to work in the Temple of the Lord.”[13] The Māori Saints brought with them hundreds of ancestral names, and members in Hawaiʻi eagerly joined with them to help complete the work. The presence of the Māori Saints seemed to spark greater interest in the temple, prompting President Waddoups to write: “These have been wonderful days for the Temple work. We have taken as many as 55 through in one company. I feel that a new era is dawning for the Temple work in this land.”[14]

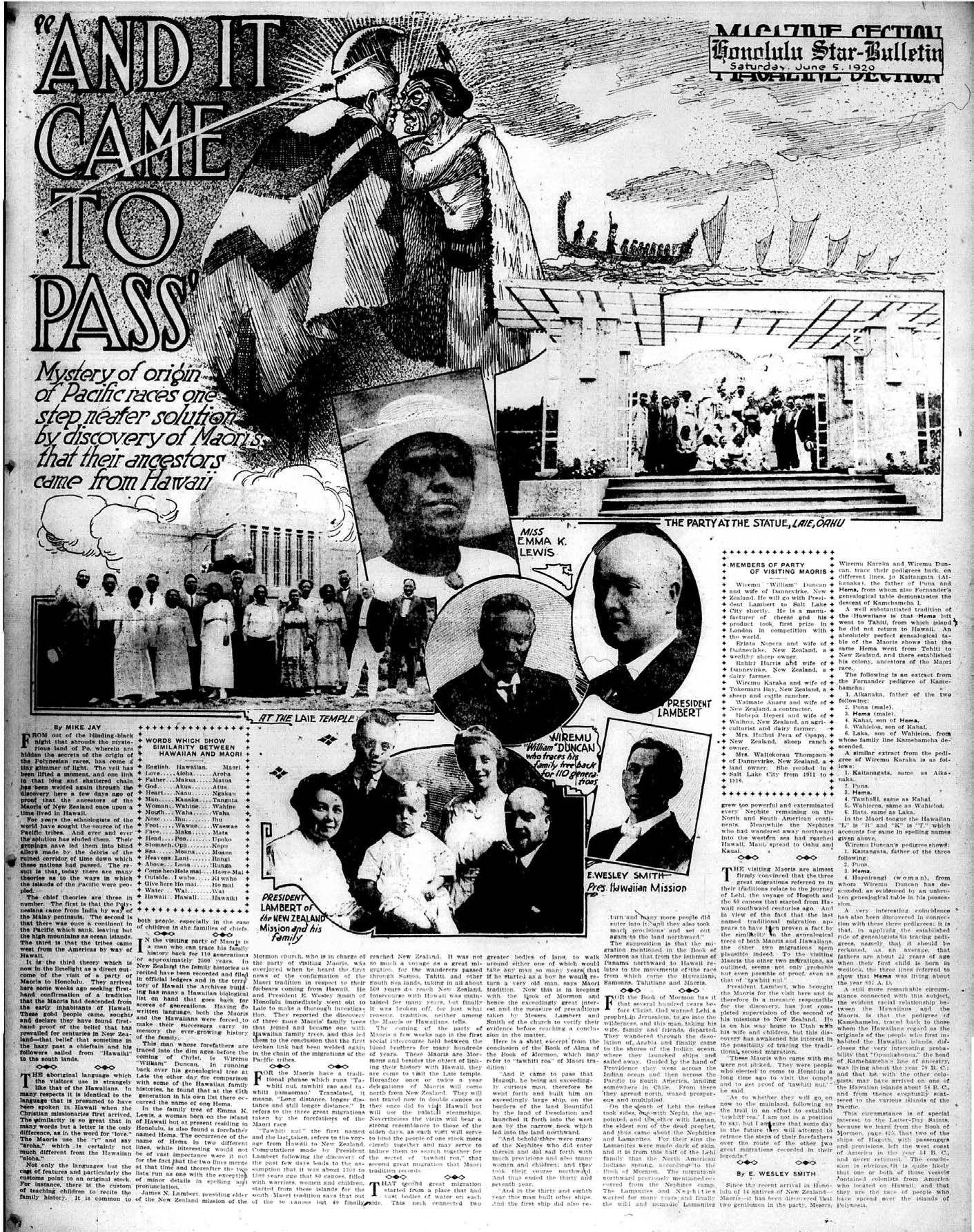

Beyond temple work, the 1920 Māori temple group raised an astonishing amount of interest in the broader Hawaiian community. As mentioned, the Māori Saints had compiled and brought with them lengthy genealogies. As these genealogies were prepared for temple ordinances, Duncan McAllister, the temple recorder, noted a connection between these and the Hawaiian genealogies he had previously arranged.[15] At that time there was considerable public and scientific interest in Polynesian heritage,[16] and word of this shared genealogy between Hawaiians and Māori spread through the newspapers.[17]

In mid-June, a reception for the Māori Saints was hosted by the Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club. Twenty-five hundred attended, with former territorial governor Sanford B. Dole speaking and the Reverend Akaiko Akana as master of ceremonies. Princess Kawananakoa occupied a seat on the stand with the Māori guests. A program consisting of Hawaiian and Māori chants, games, and songs was given, and the Royal Hawaiian Band furnished the music.[18]

On one occasion Princess Kawananakoa entertained the Māori visitors in her home, and in another event the Daughters of Hawaiʻi hosted the Māori party in the Queen Emma Summer Palace, where they discussed similarities between Hawaiian and Māori traditions.[19] Just before their return to New Zealand, the Māori Saints visited with Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole and his wife. Hawaiian Mission president E. Wesley Smith noted that the Māori Saints’ visit “has not only been fraught with interest, but has opened up new and vast fields of endeavor here in the islands. It has been an epoch making event.”[20]

The 1920 Māori temple trip was the first of three trips that members from New Zealand would make to the Hawaii Temple in the 1920s, each of which faced its own challenges. For example, as members were preparing for another trip to the Hawaii Temple in 1929, mission president John E. Magleby learned that the government was demanding a large deposit before it would consider issuing passports. Magleby had to challenge this matter all the way to the prime minister before it was satisfactorily resolved. Yet other demands were imposed, such as prepurchasing return tickets, providing proof of sponsorship in Hawaiʻi, and obtaining a medical exam, making the trip tenuous up to the last minute. Despite these hindrances, the Saints and their leaders persisted, and in 1929 twenty-one Māori members finally made their journey to the Hawaii Temple.[21] Adding value to the effort of these Saints, New Zealand Mission secretary Orrice L. Murdock observed that those who went to the temple “all returned with renewed spiritual vigor, to be pillars of strength in building up the cause of righteousness in the midst of this distant branch of the house of Israel.”[22]

Of these Māori temple trips, Zipporah Stewart observed, “Many of them spent their last dollar and life-time savings to make the trip to the Hawaiian Temple. They stayed at Lanihuli [the two-story former mission home near the temple]. . . . Early in the morning we would hear them singing, ‘Who’s On the Lord’s Side, Who?’ and other hymns as they marched up the hill to the temple to do endowment for themselves and their kindred dead. . . . How grateful these dear natives were for the privilege of going to do work they had longed to do for a lifetime. Their singing had such a sweet charm and harmony that we shall never forget.”[23]

Distances in the Pacific are vast. Traveling from New Zealand to Hawaiʻi is farther than traveling from Salt Lake City to Hong Kong, well over seven thousand miles one way. Further, Church members in New Zealand often lived in indigent circumstances, and government opposition and bureaucracy at times made outside travel difficult, if not prohibitive. Yet they found a way to get to the temple—some to Utah in the late 1800s[24] and repeatedly to Hawaiʻi in the first half of the twentieth century. The three trips in the 1920s were the beginning of a pilgrimage that would span thirty-seven years. Other than a decade-long gap surrounding World War II, such trips occurred every couple of years up until the dedication of the New Zealand Temple in 1958.[25] When President David O. McKay announced in 1955 that a temple would be built in New Zealand (the eleventh temple in operation and first in the Southern Hemisphere), the New Zealand Saints had a proven record of temple attendance earned at a distance and sacrifice as great as any in the Church.

Samoan Saints

A few Samoan members of the Church had gone to Utah seeking temple blessings years before the construction of the Hawaii Temple. But with a temple in Hawaiʻi, the number of Samoans able to experience the temple would quickly increase. Interestingly, the initial wave of Samoan Saints going to the Hawaii Temple was spurred in 1922 when Samoan Mission president John Q. Adams extended calls to various dedicated members to go to the temple in Hawaiʻi. President Adams recalled that “upon the completion of the temple at Laie, our people seemed to be seized with an intense desire to accumulate enough of this world’s goods to go to the temple, and we called some of our men and women there.”[26]

Among the Samoan families called to go to the Hawaii Temple were committed members like Aulelio and Sina Anae.[27] President Adams related the following in general conference:

In the Hawaiian mission field now, there is a man from Samoa, with his wife and seven children. . . . We said to this man, Aulelio, “It is 2,500 miles, which is a long ways off, but if you can secure enough to go there, go and take your wife, and go as soon as you desire.” This man had labored as a missionary for twenty years, without pay, something that people of the world cannot realize or appreciate. Of course, he could not accumulate much, but through the blessings of God, he was able to sell his home and sell his rolls of matting that he used for chairs and bedding, and everything in the world they owned, four or five head of cattle, and ducks and chickens, and managed to scrape together $600 or $700, took the entire amount to buy their passage, and they are now in Laie, working for the salvation of the vast numbers of Samoans who have preceded them to the other side of the veil. Would you and I do that?[28]

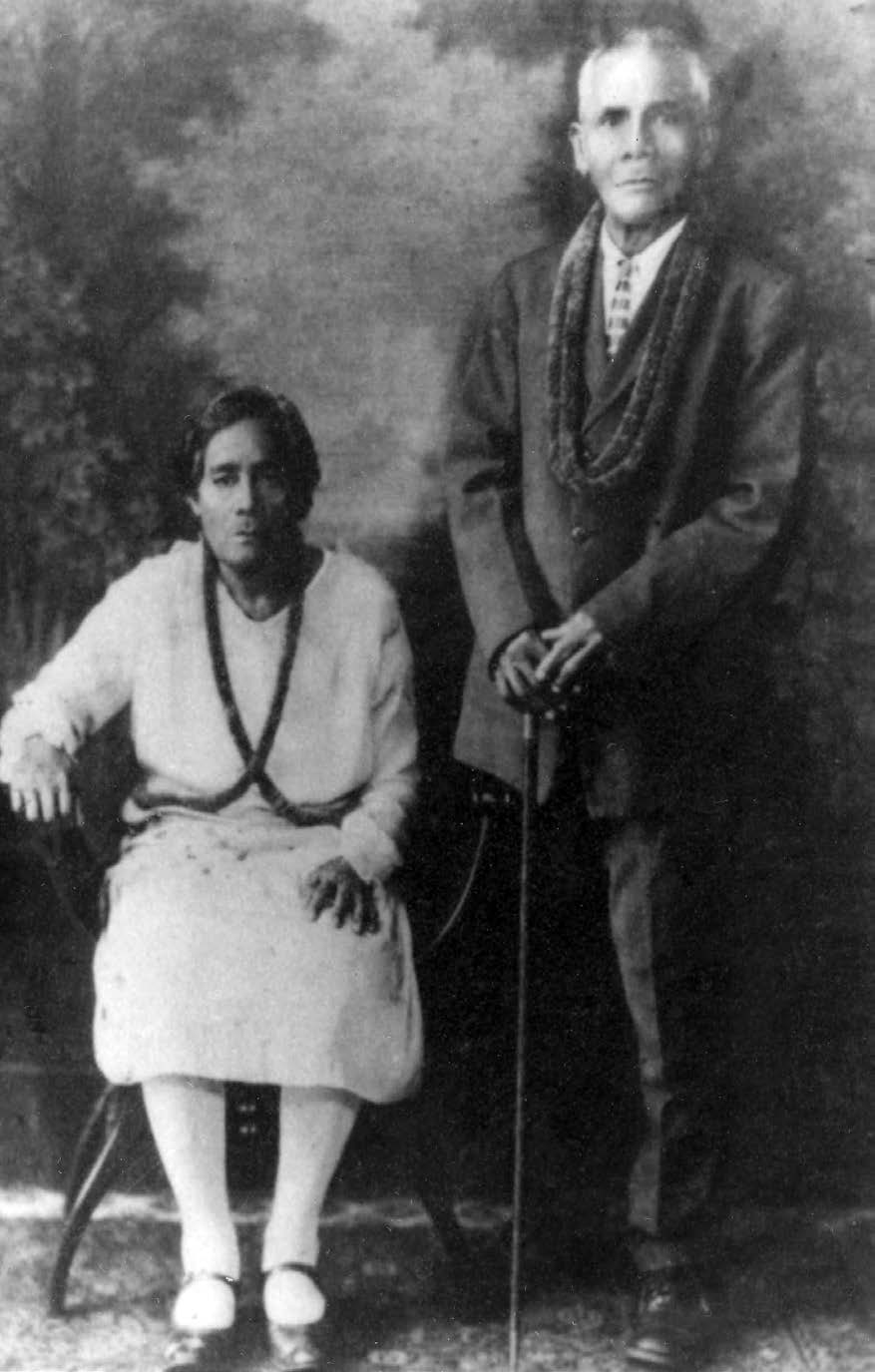

For the Anaes and other families living in American Samoa (an American territory), governmental permission to travel to Hawaiʻi was relatively open. Yet for those families called from Western Samoa, such passage was prohibitive. Facing stringent travel restrictions yet determined to answer their call to go to the temple, Opapo and Toai Fonoimoana moved their family from Sauniatu, on the island of Upolu in Western Samoa, to Mapusaga, on the island of Tutuila in American Samoa. It then took the Fonoimoana family five years to meet the residency requirements and raise the needed money to realize their goal.[29] Of those five years, Opapo and Toai’s son noted, “Persecution was particularly acute in Tutuila, and it caused Opapo much sorrow though it never shook his faith.”[30] The Fonoimoana family finished their journey in 1928, receiving their temple blessings in Hawaiʻi that November.[31]

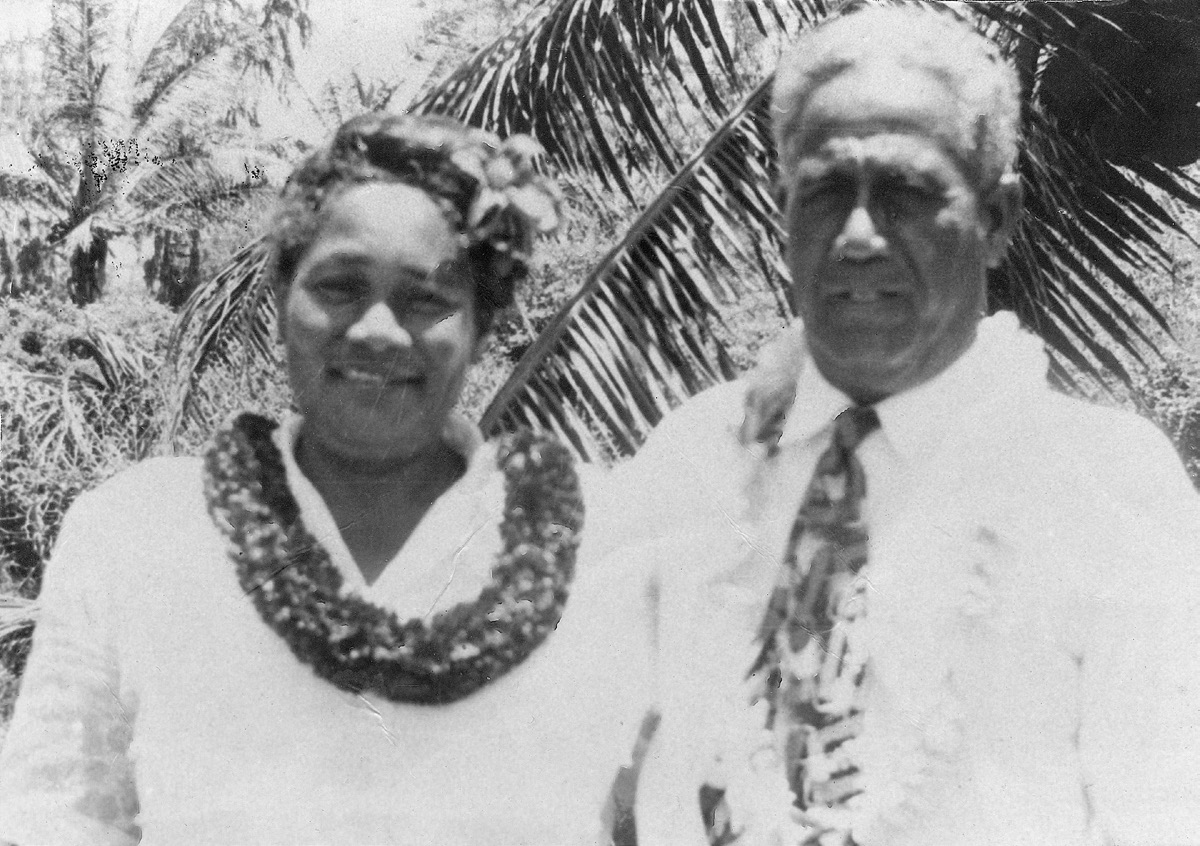

Called by their mission president to attend the Hawaii Temple, Toai and Opapo Fonoimoana moved their family from Western Samoa to American Samoa, where they lived for five years to meet the residency requirements and raise the needed money to attend the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Called by their mission president to attend the Hawaii Temple, Toai and Opapo Fonoimoana moved their family from Western Samoa to American Samoa, where they lived for five years to meet the residency requirements and raise the needed money to attend the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Beyond those that were formally called, other Samoan Saints felt equally compelled to go to the temple. One such family was Muelu Taia and Penina Ioane Meatoga. While living in the village of Mapusaga on Tutuila, Penina had a dream. Family members recount that in this dream she traveled to a strange land and saw a white building on a hill in the middle of green fields, and a man appeared beckoning her to this building. When this dream was shared with the presiding mission elder at Mapusaga, he confirmed it was the Hawaii Temple and endorsed the family’s efforts to get there. By raising livestock and making copra, the Meatogas eventually raised the necessary funds for their growing family to relocate to Lāʻie,[32] where their family was sealed in 1928.[33]

An unknown number of Samoan Saints went to Lāʻie, completed their temple work, and returned to Samoa. But others decided to remain in Lāʻie and send for the rest of their family to join them.[34] John Q. Adams, who as Samoan Mission president had called a number of these families to go to the temple, also moved to Lāʻie with his family in 1926 and managed the plantation store, a choice that no doubt helped these Samoan families assimilate into their new community.[35]

Although she was a small child at the time, Vailine Leota Niko recalled how her family was warmly welcomed into the community of Lāʻie. She recalled being given “our own little house which was heaven to us.” She continued, “There was not a time when you passed a house and where the head of the family or anyone would [not] come out and say ‘Hele Mai,’ [or] ‘Hele mai e ai,’ [meaning] ‘come in and have something to eat,’ or ‘come in.’ They were happy and they welcomed you to their place and they were so hospitable.” Of these Samoan immigrants, historians Moffat, Woods, and Walker added: “The obvious reason Samoans stayed in Laʻie was to be close to a temple, but Laʻie also gave their families more educational and economic opportunities than were available in Samoa. Some of the Samoans found work on the plantation. Others made and sold handicrafts to tourists who came out to see the temple. Associated with this activity was a replica Samoan village constructed by the Toa Fonoimoana family across from the temple. The village became a tourist destination on its own, as a display of Samoan life and culture.”[36]

Beckoned to attend the Hawaii Temple in a dream, Muelu Taia and Penina Ioane Meatoga raised livestock and made copra until they could raise the necessary funds for their growing family to relocate to Lāʻie, where their family was sealed. Courtesy of Meatoga descendants.

Beckoned to attend the Hawaii Temple in a dream, Muelu Taia and Penina Ioane Meatoga raised livestock and made copra until they could raise the necessary funds for their growing family to relocate to Lāʻie, where their family was sealed. Courtesy of Meatoga descendants.

By 1929, one decade after the completion of the temple, there were approximately 125 Samoans living in Lāʻie (about 25 percent of the village population).[37] A Church leader who worked among the Samoans in Lāʻie for many years said, “The early group of Samoans who came up, the ones who came in the twenties, were the cream of the crop from the Samoan mission. They came here with a sincere desire to do good for themselves and the Church. They came here to do Temple work.”[38] Though impossible to quantify, it is astonishing to consider the generational impact on temple work these Samoan families have had because they chose to make their home next to the Laie Hawaii Temple.

Tahitian and Tongan Saints

Although a few individuals or families may have made the journey, it does not appear that any organized groups from Tahiti or Tonga traveled to the Hawaii Temple in its first few decades of service. However, Tahitian Saints working under the direction of mission president Ole Bertrand Peterson twice submitted names to the Hawaii Temple in 1924.

These lists of names were gladly received by President Waddoups. Yet ever the gentle teacher of temple procedure, President Waddoups responded to the Tahitian mission president via letter, kindly reminding him of a long-standing practice associated with proxy temple work: remuneration.[39] Policy of that era reads, “When proxies have to be obtained to act in endowments for the dead, which occupies the time of an entire session in Temple work, it is customary to pay such proxies a small sum [between 50 and 75 cents], to partly remunerate them for personal expenses.”[40] In his letter President Waddoups explained:

You perhaps know that in all the Temples arrangement has been made whereby poor men and women, who are worthy, may go to the Temple and work on the records of others than their own blood relations, and receive a slight financial remuneration for the same. The plan adopted is this, those who send their family names to the Temple for Endowment work, who are unable to attend to the work in person, may send with these names [modest remuneration]. This amount is given to the man or woman who takes out the Endowments for the dead individual. We have a number here who need such financial help, when they work in the Temple. . . . It takes the better part of one day to do the necessary Endowment work for one individual.[41]

Fully aware that those who submit family names for temple work may themselves be poor, President Waddoups offered that each Relief Society organization throughout the Tahitian Mission could establish a temple fund for this purpose. This approach had been used in Hawaiʻi with success.[42] That said, President Waddoups twice implored President Peterson to “remember . . . that there is often an opportunity to give these names to people who come to do Temple work and who have no names of their own, and who do not need nor wish financial help, so in any event send to us your work whether you are able to send any money or not, and we will do all we can to get it done.”[43]

It is important to remember that all temples built before the Hawaii Temple had weathered extreme economic challenges and that only seventeen years earlier, in 1907, had the Church itself become debt-free. The remuneration policy had been implemented in difficult times and was maintained through meager times. Yet perhaps most insightful in this policy is its implicit assertion that members themselves are responsible for their kindred dead. Others may assist, but the duty belongs to individual members. And if they cannot do the ordinance work for their own family lines, they should be willing to assist others, if needed, to ensure that the work is done in a timely manner. As the scripture reads, “He shall turn . . . the heart of the children to their fathers” (Malachi 4:6; emphasis added). This practice of modest remuneration, in some form, continued well into the latter half of the twentieth century.[44]

Mention of remuneration aside, President Waddoups’s most urgent direction in his 1924 letter to the Tahitian Saints was that they record their oral genealogies.

We find in all Polynesian countries that the genealogies of the people are kept in chants and songs, for many generations. These records are not recorded, but are kept by memory from one generation to another, and handed down much as they were among Hebrew peoples. These verbal genealogies, should now be collected by us, and faithfully preserved. . . . They should be placed where possible in family groups. Keeping them in the order of their birth, starting as far back as you can go, and following down the line to the present generation if possible.[45]

President Waddoups added that they should record these genealogies “as soon as possible,” noting that those “who know these verbal genealogies are old and fast leaving us. When they die this vast amount of information concerning their people die[s] with them.”[46]

When President Peterson responded a few months later, he expressed gratitude for the direction and reported that he had “appointed the Relief Societies of our various branches as Temple Committees—to take care of both the genealogical and financial part of the work—and trust the results will be satisfactory.” He enclosed twenty dollars as remuneration for the names previously sent.[47]

This exchange of letters provides a notable case study of how temple work, in its infancy, proceeded throughout the Church in the Pacific and Asia. Because desire to participate was not always attended by a clear understanding of the procedures and exactness associated with the work, instruction and clarification were often needed. Yet to the Saints’ credit in Tahiti and other Pacific Island nations, as well as in Asia, such correction was welcomed and then implemented in furthering the work of the temple.

Like the Tahitians, the Tongan Saints also gathered their genealogies and sent names to the Hawaii Temple.[48] Mission and district conferences in Tonga often held genealogical sessions, and district and branch genealogical committees were formed. Reporting on the Tongan Mission, the Improvement Era in 1928 stated that “much success has been attained in gathering genealogy and names for baptism for the dead from the Saints and outsiders, especially from the chiefs along the lines of the kings of these islands.”[49]

Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Saints

Beginning in the 1850s, plantation owners in Hawaiʻi began importing contracted laborers to meet the needs of a growing sugar industry. By the early twentieth century, thousands of laborers from China, Japan, Portugal, Korea, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and other countries had moved to the islands, completed their sugar plantation contracts, and chosen to stay. This immigration had dramatically altered the demographics of Hawaiʻi, and efforts to share the restored gospel among Hawaiʻi’s many nationalities markedly expanded in the 1920s. In noting the success of these efforts, mission reports increasingly mentioned the cosmopolitan nature of Hawaiʻi’s Church membership. In 1926 the Improvement Era published a message from the Hawaii Mission under the heading “The Saints of Twelve Languages Taught How to Live.” A portion of the report explained, “Hawaii is known as the melting pot of the world, and it might be interesting to note that there were eleven races of the earth represented at the meetings who were baptized members of the Church; namely English, Hawaiian, German, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese, Negro [African] and P[ue]rto Rican.”[50] Mission records would also show Tahitians, Tongans, Marshallese, and other nationalities among Church membership in Hawaiʻi in these early years.[51]

This international presence within the Church began permeating the temple as well. President Waddoups stated, “It is, so far as I know, our pleasure to have done the first [temple] work for any living persons of the following races, in any Latter-day Saint temple: Chinese, Japanese, and Korean,”[52] and there were likely others.[53]

Chinese Saints

In 1919 President Waddoups recorded in his journal that Henry Aki was the first Chinese person to receive his temple endowment. In 1949 the Akis were among those sent to establish missionary work in China. Second row, from left: Hilton Robertson, Sai Lang Aki, Hazel Robertson, Elva and Matthew Cowley. First row: Henry Aki (far left), Carolyn Robertson (center). The three others were crew members of the USS President Cleveland, docked in Hong Kong at the time. Courtesy of John Aki.

In 1919 President Waddoups recorded in his journal that Henry Aki was the first Chinese person to receive his temple endowment. In 1949 the Akis were among those sent to establish missionary work in China. Second row, from left: Hilton Robertson, Sai Lang Aki, Hazel Robertson, Elva and Matthew Cowley. First row: Henry Aki (far left), Carolyn Robertson (center). The three others were crew members of the USS President Cleveland, docked in Hong Kong at the time. Courtesy of John Aki.

Although initially uncommon, the first Chinese began joining the Church in Hawaiʻi in the 1870s.[54] Yet by the temple’s dedication there were a modest number of Chinese members, and likely the first to be endowed was Henry Wong Aki. The day after Christmas 1919, President Waddoups recorded in his journal, “We have with us today Bro Henry [Wong] Aki so far as I know the first Chinaman to receive his Endowments.”[55] After meeting Henry Aki in 1924, Apostle Richard R. Lyman wrote: “He is a full-blooded Chinaman who is an excellent Church worker. . . . This splendid man stands ready, he says, to preach the gospel in his native land or elsewhere if the Church authorities desire to have him do it.”[56] Henry and his Chinese-Hawaiian wife, Sai Lang Akana Aki, traveled of their own accord to China in 1930, returning with numerous names for temple work.[57] And in 1932 Henry Aki was invited by the Hawaii Mission president “to take charge of the missionary work among his people” in Hawaiʻi. “He willingly and joyfully accepted,” as did his wife Sai and Sister Mary Tyau, who were called to assist. “They began to work among their people with great success.”[58]

Thus it would come as no surprise that when Apostle Matthew Cowley was asked by the First Presidency in 1949 to establish the work in China,[59] he asked Henry and Sai Aki to assist. The Akis were among a small group on Victory Peak in Hong Kong as Elder Cowley prayed, establishing the Chinese Mission. The Akis then served as mission counselors in establishing the newly made mission.[60]

Japanese Saints

Tsune Nachie immigrated to Lāʻie, where in 1923 she was among the earliest Japanese Saints to enter the temple and later became a temple worker, likely the first from her country. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Tsune Nachie immigrated to Lāʻie, where in 1923 she was among the earliest Japanese Saints to enter the temple and later became a temple worker, likely the first from her country. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Apostle Heber J. Grant dedicated Japan for the preaching of the gospel in 1901. In 1905, after careful observation and study, Tsune Ishida Nachie, the mission housekeeper and cook, was baptized. A stalwart member with particular interest in the Book of Mormon, she was likely the leading force for the redemption of the dead in Japan at that time. She pressed the elders for more information about temple work and gathered numerous names for temple ordinances.[61] Knowing her desire to visit the temple and mindful of her advancing age (mid-sixties), the missionaries, who viewed her as a second mother, obtained donations through letters to former missionaries that enabled Sister Nachie to immigrate to Lāʻie, where in 1923 she was among the earliest Japanese to enter the temple and likely became the first Japanese temple worker.[62] For many years she lived in Lāʻie, working in the temple and attending to her self-driven mission to share the gospel among the Japanese in Hawaiʻi.[63] Olivia Waddoups considered among her choicest memories in the Hawaii Temple “the keen insight into the ceremonies possessed by Sister Tsun[e] Nachie, our Japanese friend and sister.”[64]

In 1932 a group of Japanese members and a few others were asked to work among the Japanese people of Oʻahu. Among those called was Tsune Nachie. At the time living in a small apartment connected to the Honolulu mission home, “she went out each morning with her church books and a few pamphlets, tied in a handkerchief, and visited diligently among her people and preached the gospel to them.”[65] Then missionary Edward L. Clissold (who later served as temple president) simply said of Sister Nachie, “A saint, if ever there was one, a wonderful woman.”[66] She shared the gospel and regularly attended the Hawaii Temple until she was physically unable to do so, passing away in December 1938.[67]

Korean Saints

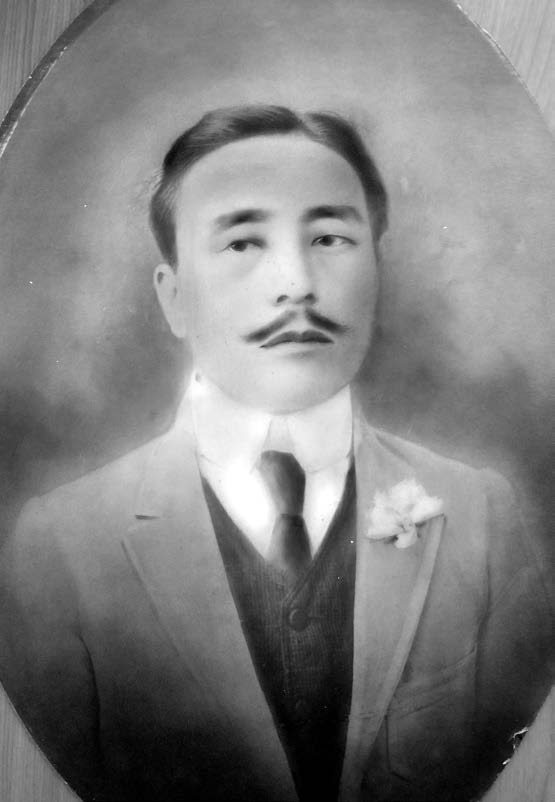

Born in Seoul, Korea, Chai Han Kim was among the earliest Koreans to immigrate to Hawaiʻi. Strong spiritual manifestations led him to join the Church and later be sealed with his family in the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Mark Piena.

Born in Seoul, Korea, Chai Han Kim was among the earliest Koreans to immigrate to Hawaiʻi. Strong spiritual manifestations led him to join the Church and later be sealed with his family in the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Mark Piena.

Born in Seoul, Korea, Chai Han Kim was among the earliest Koreans to immigrate to Hawaiʻi in the early 1900s. He established himself on the Big Island, becoming a foreman of one of the plantations on the Hāmākua Coast and supervising Korean immigrant workers. He later married Susie Kanohokuahiwiokalani Wela, and around 1920 they moved their growing family to Kipapa Camp #5, another Korean camp in the pineapple fields of central Oʻahu. It was then that he had a strong spiritual manifestation directing him to go to Wahiawa and find a church. Once there he went to a church whose minister spoke Korean, but was told that his manifestation was not from a divine source. Later he had another manifestation, and he and his wife walked to Wahiawa again. As they crossed the bridge into Wahiawa, they saw a couple sitting under a tree and asked them where to find the church. The surprised couple said they were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and took them to the branch president. The family was baptized in 1927 and later sealed in the temple.[68]

While it is possible that Chai Han Kim was the first Korean to be endowed in a temple,[69] of more importance is the generational contribution of the Kim family to the Church in Hawaiʻi and abroad. Though Chai hardly spoke any Hawaiian or English, he took his family to the temple and faithfully attended church every week until he was too old to walk, thus providing a legacy of faith that has affected generations.

A Growing International Reach

These stories of dedicated temple service illustrate the early international reach of the Hawaii Temple. Chinese, Māori, Samoan, Japanese, Korean, Filipino,[70] and other Latter-day Saints of diverse ethnicities found their way to the Hawaii Temple in the early decades of its existence. From its beginning, the Hawaii Temple routinely accommodated patrons from different cultures speaking different languages. This international reach is a hallmark of the temple’s hundred-year history—and remains a striking example of the Church’s early effort to carry the fulness of the gospel to all kindreds, tongues, peoples, and nations.

Notes

[1] “The Temple had just been completed three or four years, and the older people of the Village went to the Temple and worked at the temple.” Alberta Burningham, OH-31, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives), 4. In his journals, President Waddoups often refers to the “regular” or “usual” patrons from the community who attend the temple.

[2] Flora Kapualahaole Salm Soren-Butt, interview by Fred Woods, 8 August 2005, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[3] See George E. M. Mahi, OH-135, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 15.

[4] See Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1915. See also “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, 11 January 1920, 5.

[5] See Marjorie Newton, Tiki and Temple: The Mormon Mission in New Zealand, 1854–1858 (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2012), 139.

[6] See Annie M. Atkin, New Zealand mission journal, 14, 16, 22 May 1917, 41, William Frank Atkin Papers, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), quoted in Newton, Tiki and Temple, 141.

[7] See Newton, Tiki and Temple, 157.

[8] A list of those who were able to attend can be found in Duncan M. McAllister, “Genealogical Records Relationship,” Improvement Era, September 1920, 996.

[9] See Walter J. Wright, “Hawaiian Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 20 July 1920, 42; and Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 23 July 1920.

[10] The families of Charles John Lehuakona Broad and his son John Edwin Broad had lived in Iosepa, Utah, and moved to Lāʻie after the temple was announced.

[11] See William M. Waddoups, journal, 17 May 1920, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[12] See Waddoups, journal, 3 June 1920.

[13] Patrick L. Carroll, “A Letter to My Grandson, Philip Carroll,” FamilySearch.org.

[14] Waddoups, journal, 14 June 1920.

[15] See Duncan M. McAllister, “Evidence as to Origin of the Polynesian People,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 22 November 1921, 207–8.

[16] See “Noted Scientists Soon to Reach South Sea Isles to Study Origin of Polynesians,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 5 June 1920. The study, scheduled to begin that year, involved no fewer than eight scientists going to various parts of Polynesia.

[17] See Mike Jay, “And It Came to Pass,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 5 June 1920. See also History of the Hawaiian Mission, 5 June 1920.

[18] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 30 June 1920. See also Waddoups, journal, 14 June 1920.

[19] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 30 June 1920.

[20] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 23 July 1920.

[21] See O. Murdock, “Temple Excursion from New Zealand,” Improvement Era, August 1929, 865–67. See also Newton, Tiki and Temple, 183–84.

[22] Murdock, “Temple Excursion,” 865.

[23] Zipporah Layton Stewart, Hawaiian Temple reminiscence, MS 6124, CHL.

[24] See Newton, Tiki and Temple, 81–84.

[25] The number and frequency of Māori temple trips to Hawaiʻi is primarily based on the New Zealand Mission Manuscript History, the History of the Hawaiian Mission, and the Te Karere New Zealand Mission newspaper, all available in the CHL. Special thanks to Hyran Smith, Arapata Meha, and Riley Moffat for their research on this topic.

[26] John Q. Adams, in Conference Report, October 1924, 106.

[27] Aulelio Tameamea Poutalimati Anae and Sina Siona Leali‘ifano received their own temple blessings on 30 October 1923. See FamilySearch.org.

[28] Adams, in Conference Report, 103–8.

[29] See Tella and Mataniu Fonoimoana, OH-92, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 16.

[30] Carl Fonoimoana, “Opapo: The Power of Faith,” Ensign, July 1981, 66.

[31] FamilySearch.org records that Opapo Fonoimoana and Toai Alema Auuti received their own temple blessings on 29 November 1928.

[32] See Anna Meatoga Napoleon, Kaleo o Ko‘olauloa (Lāʻie community newspaper), 25 October 2001; and R. Eric Beaver, interview by Gary Davis, 20 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[33] According to FamilySearch.org, Muelu Taia Lauofo Meatoga and Penina Ioane received their own temple blessings and were sealed on 25 January 1928.

[34] See Bernard Francis Pierce, “Acculturation of Samoans in the Mormon Village of Laie, Territory of Hawaii” (master’s thesis, University of Hawaiʻi, June 1956), 19–20, http://

[35] See Ruth and Faelela Adams, “Thurza Amelia Tingey Adams History,” FamilySearch.org.

[36] Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, 2011), 129.

[37] See “Samoan Colony at Laie Adds Variety to Life of Windward Oahu,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 8 June 1929; and Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 129.

[38] Pierce, “Acculturation of Samoans,” 19–20.

[39] See William Waddoups to Ole Bertrand Peterson, 23 October 1924, CHL.

[40] Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, and Charles W. Penrose, “Temple Work for Church Members Abroad,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, April 1915, 54.

[41] Waddoups to Peterson, 23 October 1924.

[42] See Wilford W. King, “Hawaiian Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 11 May 1920, 389–90.

[43] Waddoups to Peterson, 23 October 1924.

[44] See David O. McKay, Stephen L Richards, and J. Reuben Clark Jr. to stake presidents, 15 December 1955, 407, quoted in Devery S. Anderson, ed., The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846–2000: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), 302; and Priesthood Bulletin, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, April 1972, 4.

[45] Waddoups to Peterson, 23 October 1924. For more information on Pacific genealogies, see Kip Sperry, “Oral Genealogies in the Pacific Islands,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The Pacific Isles, ed. Reid L. Neilson, Steven C. Harper, Craig K. Manscill, and Mary Jane Woodger (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 75–92.

[46] Waddoups to Peterson, 23 October 1924.

[47] Ole Bertrand Peterson to William Waddoups, 28 January 1925, CHL.

[48] It is not clear if any Tongans were able to attend the Hawaii Temple until the late 1950s. Tongan Mission president Mark Vernon Coombs “called a number of the local brethren to go to the Hawaii temple but no one seemed to have enough money.” Tongan Mission History, 13 April 1924, CHL.

[49] “Far-Away Tonga,” Improvement Era, January 1928, 250. “Afternoon we had a baptismal service in the temple. I did the baptizing; 185 were baptized for mostly Tongans from the Tongan Mission.” Waddoups, journal, 30 April 1929.

[50] “The Saints of Twelve Languages Taught How to Live,” Messages from the Missions, Improvement Era, December 1926, 187–88. See “Annual Conference Held at Honolulu,” Messages from the Missions, Improvement Era, June 1927, 728–29.

[51] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 1920s–1930s.

[52] William M. Waddoups, “Hawaiian Temple,” Improvement Era, April 1936, 227.

[53] See note 70 herein.

[54] See Russell T. Clement and Sheng-Luen Tsai, “East Wind to Hawaii: Contributions and History of Chinese and Japanese Mormons in Hawaii,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 2, no. 1 (1981): 12.

[55] Waddoups, journal, 26 December 1919, 98.

[56] Richard R. Lyman, Improvement Era, December 1924, 104.

[57] See Olivia Sessions Waddoups, journal, 13 March 1930 and 5 April 1930, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers.

[58] Castle H. Murphy, “A Brief Resume of the Beginning of the Work of Preaching the Gospel to the Chinese and Japanese in Hawaiʻi 1932 and 1944,” MSSH 151 or 147, box 34, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[59] See Paul Richard Sullivan, “Saints in Hong Kong Commemorate Mission’s Beginnings,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 16 July 2014, https://

[60] See H. Grant Heaton, “Missionary Work in Asia,” BYU Studies 12, no. 1 (Autumn 1971): 88–91. See also Murphy, “Brief Resume.”

[61] See Ardis Parshall, “Courage to Follow Convictions,” in Women of Faith in the Latter Days, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Brittany Chapman (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 3:128.

[62] There were a number of Japanese immigrants in Hawaiʻi who had joined the Church and likely attended the temple before Tsune Nachie’s arrival. For example, “My father [father-in-law Takie Doyle, born 25 Apr 1883 in Japan, endowed 3 December 1919 in Laie Hawaii Temple (see FamilySearch.org)] was the first Japanese to go into the temple right [when] it was dedicated over here. He and my mother took their endowment out and we were sealed, us kids where sealed to them on December 30, 1919. He was the first Japanese.” Samuel Kalama, 12 July 1978, OH-41, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 25.

[63] In the 1930 census, Tsune Nachie identified herself as a “missionary,” https://

[64] Olivia Waddoups, Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[65] Murphy, “Brief Resume.”

[66] Edward L. Clissold, oral history interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 11 June 1976, MSSH 261, box 2, 7, BYU–Hawaii Archives. See Parshall, “Courage to Follow Convictions.”

[67] For more information on Tsune Ishida Nachie, see Parshall, “Courage to Follow Convictions.”

[68] Information on the story of Chai Han Kim was obtained from his grandson Dennis C. H. Kim in an email message to the author, 1 January 2018.

[69] FamilySearch.org indicates that Chai Han Kim was endowed on 12 January 1933.

[70] The first Filipinos to receive their temple blessings likely did so in the Hawaii Temple. Thousands of Filipinos immigrated to Hawaiʻi in the early 1900s, and a number of them joined the Church and eventually attended the temple. For example, Anacleto Ribuca Battad, born in 1903 in San Vicente, Ilocos Sur, Philippines, immigrated to Hawaiʻi in 1924, was later baptized a member of the Church, and received his endowment on 19 August 1943 in the Laie Hawaii Temple (see FamilySearch.org). This was two years before what is traditionally considered the first convert baptism in the Philippines (see “Timeline of Key LDS Church Events in the Philippines,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 11 September 2017, https://