A Gathering Place in Lāʻie

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "A Gathering Place in Lāʻie," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 17–30.

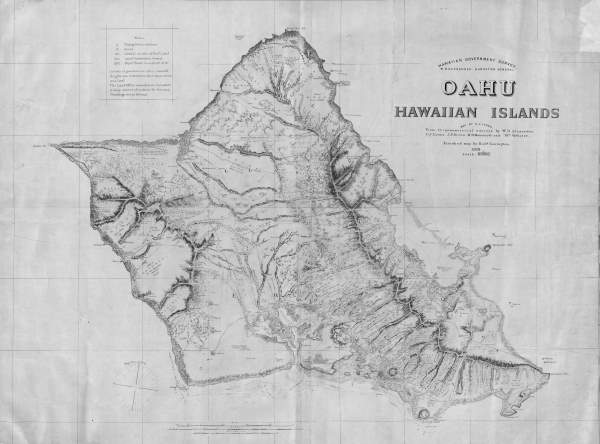

In 1865 the Church purchased 6,000 acres that included the village of Lāʻie on the northeast coast of the island of O'ahu. This location became a gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints and the eventual location of the Laie Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1865 the Church purchased 6,000 acres that included the village of Lāʻie on the northeast coast of the island of O'ahu. This location became a gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints and the eventual location of the Laie Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Like their counterparts serving elsewhere in the mid-1800s, missionaries in Hawaiʻi taught that new members should gather to “Zion” in the Utah Territory. However, in an effort to preserve a dwindling population, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi forbade such emigration.[1] When in response Brigham Young recommended that mission leaders find a location for the Hawaiian Saints to gather,[2] the Pālāwai basin on the small island of Lānaʻi was secured for this purpose in 1854.[3] Yet establishing even a small colony of Hawaiian Saints on Lānaʻi proved difficult. Then, adding to a number of challenges faced by the fledgling Church throughout Hawaiʻi, missionaries were recalled from the islands in 1858 because of the Utah War.[4] From the spring of 1858 until the arrival of Walter Murray Gibson in the summer of 1861, native members were responsible for the leadership of the Church in the Hawaiian Islands.

Captain Gibson, most noted for voyages to the East Indies, apparently saw membership in the Church as an opportunity to further his desire to establish some kind of personal kingdom in Southeast Asia. After joining the Church, Gibson petitioned a call to serve a mission to Japan and Malaysia. While en route he visited the Saints in Hawaiʻi and, noticing a void in leadership, stepped in. He used members’ money to purchase the land on Lānaʻi in his own name and eventually established himself as “Chief President,” with the island of Lānaʻi as headquarters for his intended kingdom. Some Hawaiian Church members became suspicious of Gibson, and in a letter that eventually reached President Brigham Young, they questioned Gibson’s authority and practices. In response President Young assigned Apostles Ezra Taft Benson and Lorenzo Snow—and called former Hawaiian missionaries Joseph F. Smith (age twenty-five), William W. Cluff, and Alma L. Smith—to “go to the islands and set the churches in order.”[5] Upon arrival in Hawaiʻi, the Apostles visited with Gibson. Unwilling to change, Gibson was excommunicated from the Church on 7 April 1864. Shortly thereafter Apostles Snow and Benson departed, leaving Joseph F. Smith as mission president.[6]

Though able to resuscitate a modest but foundational group of Hawaiian Saints to carry the Church forward, Smith and his companions were unable to acquire a suitable location for the Saints to gather after losing the Lānaʻi location to Gibson.[7] However, before their departure, William Cluff experienced a vision while visiting the village of Lāʻie on the northern coast of Oʻahu. Cluff recounts that after praying in secret, he was astonished to see Brigham Young walking up the path to meet him. Young commented on the beauty and desirability of the location, then said, “Brother William, this is the place we want to secure as headquarters of this [Hawaiian] mission.”[8] Further significance is given this vision by others who later understood Brigham Young to have also informed Cluff that a temple would someday be built in Lāʻie.[9] A couple months later, Elder Francis A. Hammond[10] bought the entire ahupuaʻa (land division) of Lāʻie,[11] more than six thousand acres, for fourteen thousand dollars.[12] Therefore, in January 1865 Lāʻie became the new center of Church activities in Hawaiʻi—and the eventual home of the temple.[13]

Interestingly, Lāʻie was traditionally known to have been an ancient puʻuhonua, variously translated as “city, place, or temple of refuge.”[14] Anthropologist E. S. Craighill Handy wrote: “In the Hawaiian islands were enclosures that may be spoken of as temples of refuge, which were specially built for and consecrated to this purpose. . . . Fugitives of all kinds . . . were allowed to enter the sacred enclosure, and, once in, were safe. . . . After a certain length of time they were allowed either to enter the service of the priests or to sally forth into the world again unmolested.”[15] Though under very different circumstances, Lāʻie was once again to serve as a city of refuge (see Doctrine and Covenants 115:6–8), and with the later addition of the temple, it would be viewed by many as an eternal city of refuge (see 124:36–39).[16]

Gathering to Lāʻie

Village of Lāʻie circa 1898. The large building at center is the mission home, and the larger building to its right is the Lāʻie Chapel, named “I Hemolele.” The chapel's location would later become the site of the Laie Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Village of Lāʻie circa 1898. The large building at center is the mission home, and the larger building to its right is the Lāʻie Chapel, named “I Hemolele.” The chapel's location would later become the site of the Laie Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

George Nebeker, Hawaiian Mission president from 1865 to 1873, described Lāʻie: “Our location here is a pleasant one. We are situated on the island of Oahu, near its north point, thirty-two miles from the city of Honolulu, the capital of the group. We have some three miles of coast, from which our land runs back to the center of the Island, or top of the mountain. There are five hundred acres of good, arable land lying near the sea-beach; the remainder is grazing and timber land.”[17]

In the decade following the purchase of Lāʻie, Church membership in the islands exceeded four thousand.[18] However, Lāʻie simply lacked the resources and jobs needed to gather all the Hawaiian Saints there, and despite missionaries’ repeated calls to gather to Lāʻie, only about three hundred Saints did so.[19] The plantation had both lean and profitable years but generally struggled in its opening decades. However, in 1883 the Saints were able to dedicate a beautiful chapel on a prominent hill and named it I Hemolele, and later they built a new mission home. Despite the ups and downs, the abiding purpose of Lāʻie was to help the island Saints develop character while earning an honest living, and that purpose appears to have been achieved by those who chose to gather there.[20]

Voyaging to Zion for Temple Blessings

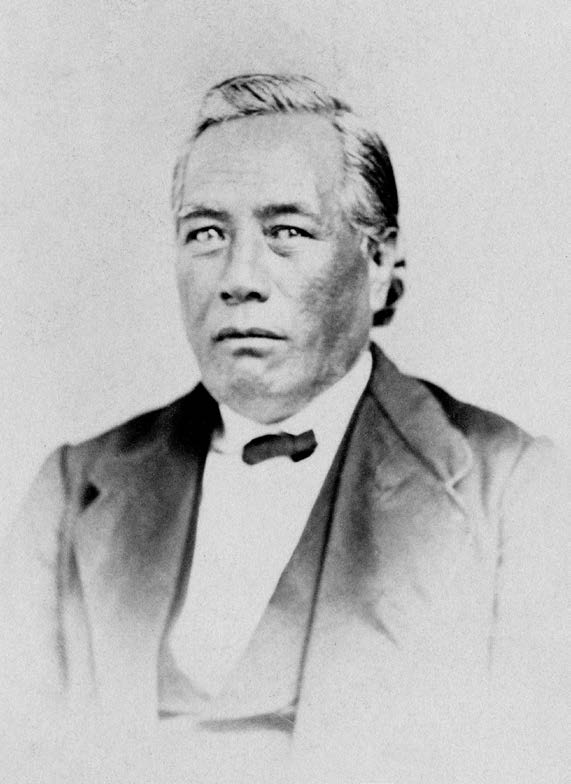

Jonathan H. Nāpela was likely the first Hawaiian, as well as the first Polynesian, to receive his temple blessings. This photo was taken during his visit to Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1869. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Jonathan H. Nāpela was likely the first Hawaiian, as well as the first Polynesian, to receive his temple blessings. This photo was taken during his visit to Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1869. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Despite lingering emigration restrictions and prohibitive travel cost, the desire of many island members to find their way to Utah where they could obtain temple blessings persisted. Likely the first Hawaiian Latter-day Saint to visit Zion was Jonathan H. Nāpela. He received his endowment on 2 August 1869, the first known Hawaiian to do so, and was baptized on behalf of deceased King Kamehameha I.[21] Upon his return to Hawaiʻi, Nāpela related his experience to King Kamehameha V. In a letter to President Brigham Young, Nāpela explained: “I informed my King that . . . I was baptized on his [Kamehameha I’s] behalf; but that he [the King] is responsible for the remainder of his ancestors buried in the earth and that their salvation rests upon him. . . . There was much astonishment before me and appreciation.”[22] Report of Nāpela’s trip seemed to ignite an even greater desire among many Hawaiian members to go to Utah so they too could receive these temple ordinances.

I Hemolele Chapel, 1899. Courtesy of Church History Library.

I Hemolele Chapel, 1899. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Gradually, restrictions on travel and emigration loosened, and a number of Hawaiian families emigrated to Utah, eventually forming a small colony of about seventy-five Hawaiians living in the northwest area of Salt Lake City in the late 1880s.[23] Although these Islanders were able to experience the spiritual blessings available in Salt Lake City, they also encountered numerous challenges. Language and cultural barriers, even prejudice, made assimilation difficult. Employment for these immigrants was generally limited to temporary and unskilled labor, and when winter came they were often the first to be let go. Former missionaries to Hawaiʻi and Church leaders, particularly First Presidency members Joseph F. Smith and George Q. Cannon, were concerned for their Hawaiian Island friends.[24]

Joseph F. Smith’s Third Mission

Owing to federally sponsored efforts against plural marriage, many Church leaders were pressed into exile. Under these circumstances, President Smith was called on a “mission” to Hawaiʻi, where he would serve from February 1885 until June 1887.[25] Having served his first mission to Hawaiʻi at age fifteen, and again at age twenty-five when dealing with the Gibson affair, Joseph F. Smith, now forty-six years old, was Second Counselor in the First Presidency and had been an Apostle for almost twenty years.

Shortly after Joseph F. Smith’s arrival in Hawaiʻi, mission president Edward Partridge recorded, “Prest. Smith spoke very feelingly telling the people that if they would keep the commandments of [the] Son [of God] they would probably have the privilege of building a temple in this land.”[26] Perhaps President Smith’s purpose was in part to dissuade Church members in Hawaiʻi from emigrating to Utah, given the difficult conditions that awaited them if they did, or to encourage strong native members to remain in Hawaiʻi and build the Church and support the struggling Church plantation at Lāʻie. In any event, President Smith’s remark made clear that building a temple in Hawaiʻi was indeed a possibility.

Furthermore, President Smith’s leadership during these two years in Lāʻie would enhance the prospects for a temple in Hawaiʻi. Under Smith’s guidance, “the church [in Hawaiʻi] was fully organized and functioning, including all the auxiliaries.”[27] Also during this time, President Smith is said to have given the “Lāʻie prophecy,” promising the plantation’s success, which repeatedly served to encourage the Saints in Lāʻie to carry on.[28] When Joseph F. Smith departed in 1887, undoubtedly Lāʻie and the Hawaiian Mission were on a stronger footing and pointed in a direction that would allow President Smith, thirty years later, to personally help realize the building of a temple in Hawaiʻi.

The Iosepa Colony

Top and Bottom: In the latter 1800s and into the early 1900s, a number of Hawaiian Saints immigrated to Utah mainly for temple blessings. This group formed a colony in Skull Valley, Utah, about 75 miles southwest of Salt Lake City. They named their colony Iosepa, meaning “Joseph,” after their beloved Church leader Joseph F. Smith. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives. Photo of Skull Valley looking toward Iosepa. Courtesy of Gary Davis.

Top and Bottom: In the latter 1800s and into the early 1900s, a number of Hawaiian Saints immigrated to Utah mainly for temple blessings. This group formed a colony in Skull Valley, Utah, about 75 miles southwest of Salt Lake City. They named their colony Iosepa, meaning “Joseph,” after their beloved Church leader Joseph F. Smith. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives. Photo of Skull Valley looking toward Iosepa. Courtesy of Gary Davis.

However, the desire of Saints in Hawaiʻi to receive temple blessing and to gather with the main body of members in Utah did not dissipate. In February 1889 Hawaiian Mission president William R. King notified President Wilford Woodruff that more members in Hawaiʻi were planning to immigrate to Utah.[29] Concerned about conditions in Salt Lake City, King asked President Woodruff to settle these Saints “in a country place not too far removed from Salt Lake City.”[30] A month after King’s letter arrived, the First Presidency formed a committee to locate a suitable Utah location for the Hawaiian Saints to gather. Among several possibilities, the committee voted to purchase the John T. Rich ranch (seventy-five miles west of Salt Lake City) in Skull Valley, Tooele County.[31]

At the time that ranch was likely the closest available and potentially profitable location to Salt Lake City and the temple—the latter being the main reason the Hawaiians had immigrated to Utah.[32] They named their town Iosepa, the Hawaiian word for “Joseph,” after beloved missionary and Church leader Joseph F. Smith. Iosepa became home to the Hawaiian Saints in Utah for the next twenty-eight years (1889–1917). Similar to other Hawaiian Saints, Maryann Nawahine said of her family’s settlement at Iosepa, “My father and mother had one purpose, and that was to enter the temple in Salt Lake City.”[33]

Other Islander Efforts to Attend the Temple

Extraordinary as the Iosepa colony was, numerous Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders seeking temple blessings in the late 1800s and early 1900s did not settle at Iosepa or in Salt Lake City, but rather journeyed to a temple in Utah, received the ordinances, and returned to the islands—all at considerable cost. Former missionary to Hawaiʻi Castle H. Murphy recalled: “Some . . . sacrificed so much to come to Utah to receive their endowments and sealings. . . . They used their life’s savings to make the trip and returned home in debt.” However, of those who returned, Murphy added, “They kept their covenants . . . and died true to the faith.”[34] For a temple to be built anywhere, there needs to be a foundation of faithful and covenant-seeking Saints. When a temple in Hawaiʻi was finally announced, few groups of members living far from the main body of the Church had proved to be so faithful and desirous of temple blessings longer than the Saints in the Pacific.

Notes

[1] See Fred E. Woods, Kalaupapa: The Mormon Experience in an Exiled Community (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book 2017), 12n19.

[2] See Brigham Young to George Q. Cannon, 15 June and 30 September 1853, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL). See also Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter BYU–Hawaii Archives), 18 August 1853, quoting the journal of George Q. Cannon.

[3] For more detail about the Lānaʻi gathering experience, see Fred E. Woods, “The Pālāwai Pioneers on the Island of Lanai: The First Hawaiian Latter-day Saint Gathering Place (1854–1864),” Mormon Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (Fall 2004): 3–35; and Raymond Beck, “Pālāwai Basin: Hawaiʻi’s Mormon Zion” (master’s thesis, University of Hawaiʻi, 1972).

[4] The Utah War was a dispute between the Church and the US government, which viewed the Church as being in rebellion against US authority.

[5] Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 18 January 1864, CHL.

[6] For an overview of Walter Murray Gibson’s involvement with the Church in Hawaiʻi, see R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018), 105–19; Gwynn Barrett, “Walter Murray Gibson: The Shepherd Saint of Lanai Revisited,” Utah Historical Quarterly 40, no. 2 (1972): 142–62; and R. Lanier Britsch, “Another Visit with Walter Murray Gibson,” Utah Historical Quarterly 46, no. 1 (1978): 65–78.

[7] For more detail on the efforts to reorganize the Church in Hawaiʻi after Gibson, see Eric Marlowe and Isileli Kongaika, “Joseph F. Smith’s 1864 Mission to Hawaii: Leading a Reformation,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill, Brian D. Reeves, Guy L. Dorius, and J. B. Haws (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013), 52–72.

[8] William W. Cluff, “Acts of Special Providence in Missionary Experience,” Improvement Era, March 1899, 363–65. See William W. Cluff, “My Last Mission to the Sandwich Islands,” in Fragments of Experience (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1882).

[9] The first written account connecting Cluff’s vision to a temple being built in Lāʻie appears to be that of Samuel Woolley in a general conference address in 1916 (more than fifty years later). President Heber J. Grant would repeat this connection at the dedication of the Hawaii Temple in 1919.

[10] Francis A. Hammond had a vision similar to Cluff’s when considering the purchase of Lāʻie. “I saw President Young approach me. Said he, ‘This is the place to gather the native Saints to.’” In Marvin E. Pack, “The Sandwich Islands Country and Mission,” The Contributor 17, no. 11 (September 1896): 693.

[11] In ancient Hawaiʻi, an ahupuaʻa was a land division. Each island was divided into several moku (districts), and each moku was divided into an ahupuaʻa—generally narrow, wedge-shaped land sections that ran from the mountains to the sea. “The pie-shaped land division allowed the inhabitants of the area to hunt wild game and to collect timber from the mountains, to farm in the midlands and down to the beach, and to fish in the ocean.” See William Kauaʻiwiulaokalini Wallace III, “Lāʻie: Land and People in Transition,” in World Communities: A Multidisciplinary Reader (Lāʻie, HI: Pearson Custom Publishing, 2002), 5–6.

[12] Francis A. Hammond report to Brigham Young, telegraph dated 21 February 1865, CHL.

[13] Though Lāʻie was the gathering place and headquarters of the Church, congregations also developed in other areas throughout the islands. For a detailed history of Lāʻie, see Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011).

[14] See Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “Honaunau,” https://

[15] E. S. Craighill Handy, Polynesian Religion, Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 34 (Honolulu: The Museum, 1927), 182–83.

[16] See remarks by Samuel E. Woolley, president of the Hawaiian Mission, in Conference Report, October 1915, 110–12.

[17] George Nebeker, Deseret News, 27 November 1867, 334.

[18] See Britsch, Moramona, 165.

[19] See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 33.

[20] Britsch, Moramona, 192.

[21] Nāpela received his temple endowment in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, which operated from 1855 to 1889. There were no dedicated temples at the time of his visit in 1869 (St. George 1877, Logan 1884, Manti 1888, Salt Lake 1893).

[22] Fred E. Woods, “An Islander’s View of a Desert Kingdom: Jonathan Nāpela Recounts His 1869 Visit to Salt Lake City,” BYU Studies 45, no. 1 (2006): 33.

[23] See Matthew Kester, Remembering Iosepa: History, Place, and Religion in the American West (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 79–80. For more information about Iosepa, see Dennis H. Atkin, “A History of Iosepa, the Utah Polynesian Colony” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1959). Richard H. Jackson and Mark W. Jackson, “Iosepa: The Hawaiian Experience in Settling the Mormon West,” Utah Historical Quarterly 76, no. 4 (2008): 316–37.

[24] See Britsch, Moramona, 237. Thomas Anson Waddoups (president of Iosepa from 1901 to 1917) said the Hawaiian Island Saints living in Salt Lake City “weren’t assimilating successfully. . . . Employment which they were able to get was seasonal. They had starvation periods between these times. The Presidency of the Church conceived the idea that it would be much better if they could be established in a group where they could be well taken care of and associate with their own people.” Thomas A. Waddoups, partial history, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[25] See Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 136; and Joseph Fielding Smith, Life of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1969), 262. For further detail, see Russell T. Clement, “Apostle in Exile: Joseph F. Smith’s Third Mission to Hawaiʻi, 1885–1887,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society Proceedings (1986): 56–57.

[26] Edward Partridge Jr., journal, book 6, CHL.

[27] Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 47. See Britsch, Moramona, 188.

[28] See Britsch, Moramona, 188–89.

[29] William King reported in February 1889 that though he counseled the Saints in Hawaiʻi not to go to Utah, it was “impossible to hold them back. They have prayed . . . [and] feel that the Lord had opened the way for them to gather to Zion.” William King to Wilford Woodruff, 7 February 1899, quoted in Jeffery Stover, “The Legacy of the 1848 Mahele and Kuleana Act of 1850: A Case System of the Lāʻie Maloʻo Ahupuaʻa, 1846–1930” (master’s thesis, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 1997), 81–82.

[30] King to Woodruff, 7 February 1899, 81–82. See Dennis H. Atkin, “A History of Iosepa, the Utah Polynesian Colony” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1959), https://

[31] Britsch, Moramona, 237–38. Formed on 16 May 1889, the committee consisted of three former missionaries to Hawaiʻi (Harvey H. Cluff, William W. Cluff, and Frederick A. Mitchell) and three Hawaiian Saints living in Utah (J. W. Kauleinamoku, George Kamakania, and Napeha). This committee inspected a number of properties in Tooele, Utah, Weber, and Cache counties before choosing the Skull Valley site.

[32] Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 48–50.

[33] Henry and Maryann Nawahine account of Iosepa, Utah, interview, 20 July 1963, interviewed by Clinton Kanahele, Jerry Loveland, box 5, folder 6, BYU–Hawaii Archives. Note: The Endowment House in Salt Lake City was torn down in November 1889, the same year the Iosepa colony was founded, and the Salt Lake Temple was not dedicated until April 1893. For this reason the Saints at Iosepa “travelled approximately 100 miles northeast to the Logan Temple, by a horse drawn carriage, until the Salt Lake Temple was completed.” Bob and Sylvia Olsen, “Talking Story: Lāʻie Kupuna, Aunty Maleka Pukahi,” Kaleo o Koʻolauloa (newspaper), 12 March 2002.

[34] Castle Murphy to Hawaiian Temple Jubilee, 14 November 1969, Castle H. Murphy Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Quoted in Richard J. Dowse, “Joseph F. Smith and the Hawaiian Temple,” in Manscill, Reeves, Dorius, and Haws, Joseph F. Smith, 279–302.