Faithful Service amid Economic Challenge—1930s

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Faithful Service amid Economic Challenge—1930s," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 205–232.

Among other projects in the 1930s, the road leading to the temple was extended and beautified to help keep local members employed during years of economic depression. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Among other projects in the 1930s, the road leading to the temple was extended and beautified to help keep local members employed during years of economic depression. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The 1930s saw a renewed effort in genealogy, the organization of outer-island temple trips, the first stake formed in Hawaiʻi, two new temple presidents, and the first significant renovations of the Hawaii Temple. Yet permeating nearly the entire decade was a deep and protracted financial struggle, the conditions of which significantly affected the operation of the temple.

Lāʻie in Uncertain Times

By the mid-1920s, greatly expanded production of sugarcane in other tropical areas of the globe and a return to European production of sugar beets had contributed to a depression of sugarcane markets in Hawaiʻi that would last more than a decade. This downturn in sugar prices was particularly hard on Lāʻie, where for years the Church plantation had largely been devoted to production of sugarcane.

Money from the Lāʻie Plantation was important since it provided compensation for local workers and revenue needed to maintain the community school. The plantation’s revenues also supported the construction of early Church facilities throughout Hawaiʻi, including the temple.[1] To manage the mounting debt and reduce costs, the plantation’s beachfront properties were sold and in 1927 the Church-run school in Lāʻie was turned over to the territorial government.[2]

Exacerbating and prolonging these already difficult economic conditions was the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 and its decade-long effects. This economic downturn, beginning in the mid-1920s and engulfing much of the 1930s, reduced and shifted Lāʻie’s demographics. With the exception of two elders assigned to the temple’s Visitors’ Bureau, all missionaries in Lāʻie were reassigned to Honolulu.[3] Temple sessions, which at one point included seven or more per week,[4] were for a number of these years reduced to two, and for a time to only one.[5]

In 1930, amid these uncertain financial times, William Waddoups, along with his wife, was released as mission and temple president, and Castle and Verna Murphy, who had served a mission in Hawaiʻi together as a young married couple from 1909 to 1913, were called in their place. Although no longer assigned to an official Church capacity, the Waddoups family remained in Hawaiʻi another eight months, during which time Brother Waddoups noted, “I continued my work in the temple under the direction of President Murphy.”[6]

Lease of the Lāʻie Plantation

Significant to the future of Lāʻie and the temple, just days before the Waddoups family departed for Utah in May 1931, plantation manager Antoine Ivins met with his close friend William Waddoups. With the Lāʻie Plantation having experienced several unprofitable years, and in the midst of the protracted economic depression, Ivins confided to Waddoups that Church leaders were considering selling the plantation. Amenable to what Waddoups had to say in their ensuing conversation, Ivins asked him to write down his thoughts and suggestions and send them to him. In a letter dated 7 May 1931, Waddoups explained:

I shall regret very deeply the sale of Laie. . . . I am of the old school, I know what the plantation has done, in the establishment of the church here. I know something of what prestige it has brought us. I know how the entire church membership feels about it. It is their Zion, their gathering place . . . the place dedicated as their City of Refuge. . . .

If, for financial reasons, we cannot continue to manage Laie as our own plantation . . . then I hope that we may make some profitable lease. . . .

I suggest that if the leases are effected, that some man speaking the Hawaiian language, sympathetic with and fully understanding Laie . . . and above all a man and a wife, who can and will love and help the people. This man can manage affairs, . . . be a spiritual advisor, under the direction of the Mission President, perhaps assume charge of the Temple and Temple grounds, if deemed advisable, and make it possible for the Mission President to devote his entire time to the mission.[7]

It is almost certain that Ivins shared the contents of this letter with members of the First Presidency (his father, Anthony Ivins, was First Counselor at the time), and it is likely that he recommended William and Olivia Waddoups as best suited to oversee such an enterprise. This supposition is based on the fact that a month later the First Presidency called the Waddoupses to return to Hawaiʻi as plantation managers and to preside again over the temple.[8] The month after their call, the plantation lands were leased to the Kahuku Plantation for a term of twenty-five years.[9] Thus, eleven months after his release as temple president and only three months after his family’s departure from Hawaiʻi, President Waddoups and his family returned to Hawaiʻi.[10] “We were indeed happy,” wrote President Waddoups, “to again take up our labors in the temple, and be back again in Hawaii.”[11] President Murphy welcomed Waddoups’s return as temple president, noting that his assignment as mission and temple president had been “difficult to correlate.”[12]

Managing temporal affairs in Lāʻie

Not long after his return, President Waddoups wrote, “Conditions here are uncertain, and there is much depression and fear for the future. There is much unemployment on every hand.”[13] President Waddoups’s management of the temporal affairs of Lāʻie would have a direct effect on the temple, which derived most of its workers and a steady set of patrons from the community. To help maintain the temple community in these difficult times, he negotiated with the Kahuku Plantation “to hire any and all of Laie men and boys, who will work.”[14] Beyond the usual lots afforded Lāʻie residents, President Waddoups leased unused land at a modest rate to “responsible saints” who wished to farm.[15] Furthermore, he recorded, “I was appointed a member of the FERA [Federal Emergency Relief Administration] and CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] committees for the Koolauloa district. This was much to our interest as it helped materially in keeping our Laie men employed.”[16] These were among the first Depression-era relief programs under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which sought to create new jobs in local and state government.

Temple recorder Robert Plunkett was appointed forester and was able to hire a local crew of five. Brother Poi, who oversaw the road crew, continued to hire locally with additionally funded projects. And President Waddoups touted the modest employ of his “temple gang” (consisting of Henry Nawahine, Tautuaʻa Tanoai, and Toa Fonoimoana, who maintained the temple and its grounds), saying, “it is the best working combination I have ever had there.”[17]

In 1934 the Lāʻie community received President Franklin D. Roosevelt in front of the temple during his tour of Hawaiʻi. President Roosevelt is in the car beneath the archway with the temple in the background. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In 1934 the Lāʻie community received President Franklin D. Roosevelt in front of the temple during his tour of Hawaiʻi. President Roosevelt is in the car beneath the archway with the temple in the background. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

“We were poor” was a common refrain of those who lived in the temple town of Lāʻie during the Great Depression,[18] yet there was ample food. Families maintained gardens, livestock, and community taro patches that were all part of a long-established program of self-sufficiency in the gathering place of Lāʻie.[19] In the depressed economic climate, temple activity remained modest but steady throughout much of the 1930s, with occasional group visits.

A US presidential visit

In the midst of the Depression years, Lāʻie received a notable guest in front of the temple. President Waddoups recorded:

In August 1934 we had the honor and the great pleasure of entertaining President Franklin D. Roosevelt at Laie. We decorated the approach to the temple, built a large beautiful flower arch in front of the temple entrance. . . . We entertained him with Hawaiian and Samoan dance and song, and he was received by the royalty of Hawaii and Samoa in typical Polynesian style. He seemed to enjoy it and warmly congratulated us for the showing and for the work our church is doing in Hawaii. . . . The mayor of the city and county of Honolulu, the Governor of the territory, . . . and many friends congratulated us saying the entertainment was the most colorful and beautiful the President had received anywhere in Hawaii.[20]

Church Centennial, 6 April 1930

Despite its decrease in temple activity in the 1930s, Lāʻie saw a number of notable temple-related events. As part of a Churchwide centennial celebration in 1930, the Hawaiian Mission produced a pageant depicting the one-hundred-year history of the Church and its eighty years in Hawaiʻi. The pageant was presented in Honolulu from Friday, 4 April, to Sunday, 6 April, and its final scene featured the Hawaii Temple and a choir singing “A Temple in Hawaii.” Thousands attended the celebration.[21]

Although the annual missionwide conference held in April (generally a three-day event) was always one of the busiest times of the year for the temple, this “Centennial Conference of the Organization of the Church”[22] was a particularly busy time, yielding perhaps the largest crowds the temple had seen during its first decade of operation.[23]

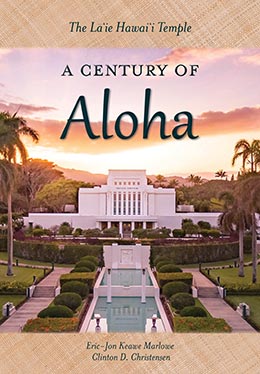

Temple painting at night by LeConte Stewart. Courtesy of Gayle Judd family.

Temple painting at night by LeConte Stewart. Courtesy of Gayle Judd family.

Amoe Meyer, who had moved to Lāʻie years earlier but was not a Church member, attended the pageant Saturday night with her member husband, Rudolph. They were accompanied by his mother, Violet Kaiwaanaimaka Meyer, and aunt Ivy E. Apuakehau, both temple workers. Having departed the pageant near midnight in their family car, as they came upon Lāʻie in the early hours of 6 April, Amoe recorded:

We noticed a glow in the west above the mountains. Everyone offered an opinion as to what it was—a cane field burning; the moon going down, etc. We were nearing Laie and the light got brighter. When we approached the road to Laniloa Point, we noticed that the light centered above the temple, which we could see clearly in its glow. It was a beautiful white light and seemed to come from great white clouds which seemed to open up above the temple.

My husband’s mother and aunt broke into song—“The Spirit of God Like a Fire is Burning.”[24]

As they drove to the temple to get a closer look, Amoe explained that the light faded, then disappeared. It was the “most beautiful sight I ever saw,” she said. “It just thrilled us.” Noting the significance of the day, the hundredth anniversary of the Church, Amoe stated, “That’s why we saw it. And we knew without a doubt that it was the true church. And so I became a member.”[25]

Capital Improvements

Two temple-related projects were undertaken in Lāʻie in the early 1930s. Initially there was no road from the temple extending directly east toward the ocean. From Kamehameha Highway, drivers used either Lanihuli Street just to the north or a meandering road from the south to get to the temple. To create a more direct access point, a road was extended one block directly east to ʻŌmaʻomaʻo Street (now Moana Street); after a short turn to the right, this road connected to Puʻuahi Street, which proceeded east to the highway. In April 1932 President Waddoups wrote, “The stone and tar is now being applied to the new road leading to the temple. We will plant royal palms on the two sides of the road, and grass and park the sides so that in a short time we will have a very beautiful approach to the temple.”[26] Decades later this road was extended all the way to Kamehameha Highway to create the striking entrance road to the temple known today as Hale Laa Boulevard.

In the same year the road was constructed, the old two-story mission home named “Lanihuli,” located only a few hundred yards from the temple, was renovated.[27] When built in 1893, the Lanihuli house was one of the most impressive homes on the windward side of the island,[28] but in 1932 it was nearly forty years old and had seen little use since the community school was given to the territory and the sister missionaries who worked there were removed. Mission president Castle Murphy had an idea for its renewed use that proved practicable:

During the past two years the Relief societies of the Oahu district have taken over the old Lanihuli Mission Home, located in Laie, which has been practically deserted for a number of years. The home has now been remodeled, renovated and painted and is being used as a haven of rest. . . . The home is also used by many who desire to go to Laie and remain over from session to session at the Temple and for a period of rest as well. Such people contribute fifty cents per day each to the Relief society for a room and provide their own food.[29]

Renewed Effort in Genealogy

The Lanihuli house was renovated in the early 1930s and would serve as temple housing for the following two decades. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The Lanihuli house was renovated in the early 1930s and would serve as temple housing for the following two decades. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

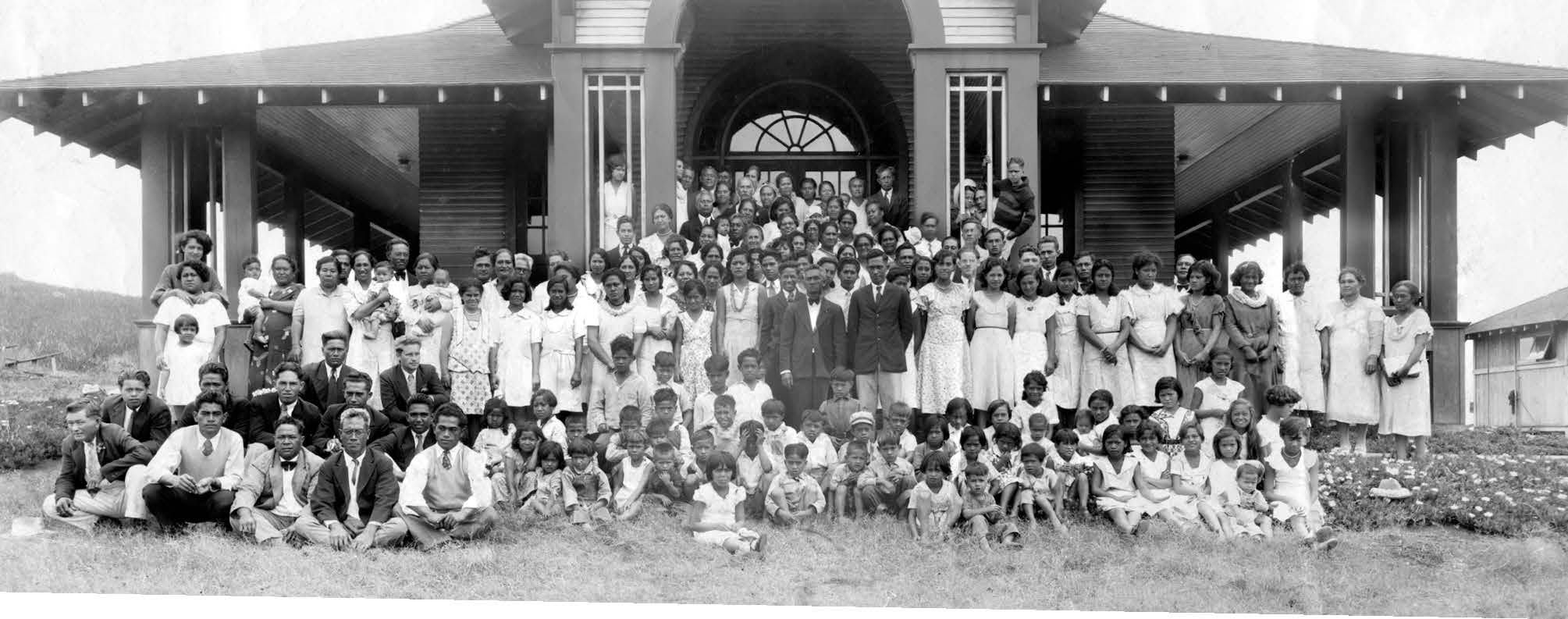

More importantly, the early 1930s also saw a renewed push for genealogy and temple work.[30] In June 1932, Albert Nawahi Like was set apart to head the Hawaiʻi Genealogy Society, which had been established over a decade earlier in 1921.[31] In response to his calling, Like traveled to Salt Lake City at his own expense “for the purpose of studying genealogical work first hand from the experts who serve there.”[32] He approached his calling as a mission, often traveling throughout the islands with another genealogy committee member as a companion.[33]

One approach then used in gathering genealogy was to review a branch’s or district’s records, identify members who had not completed a family genealogy sheet, and visit those families in hopes of helping them complete the sheet. After a long day of visiting members for this purpose near the southern tip of the Big Island in Waiʻōhinu, they were informed by a boy that there were Church members living in the community below. However, after making their way down to the house, the man inside said no members lived there. When upon their return the boy clarified that the wife was a member, not the husband, Like and his companion returned to the home. The husband then acknowledged that his wife was a member, and although they saw her in the house, he told them she could not visit because she was not feeling well. Disappointed and a bit frustrated, they left.

Set apart to lead the Hawaiʻi Genealogy Society in 1932, Albert Like devoted decades of his life to gathering genealogical data and advancing temple work in Hawaii. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Set apart to lead the Hawaiʻi Genealogy Society in 1932, Albert Like devoted decades of his life to gathering genealogical data and advancing temple work in Hawaii. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

About six months after returning from service on the Big Island, Like received a request for ordinance work for that same man. He had died of a heart attack, and his mother-in-law, a Church member, had completed the sheet and sent it in. Initially surprised, Like concluded, “Who am I to judge this; let the Lord judge it; so I sent it in.”[34] Albert Like’s decades-long contribution to temple genealogy was remarkable and remains a striking example of the contribution one person can make in the work of redeeming the dead.

Outer-Island Temple Trips

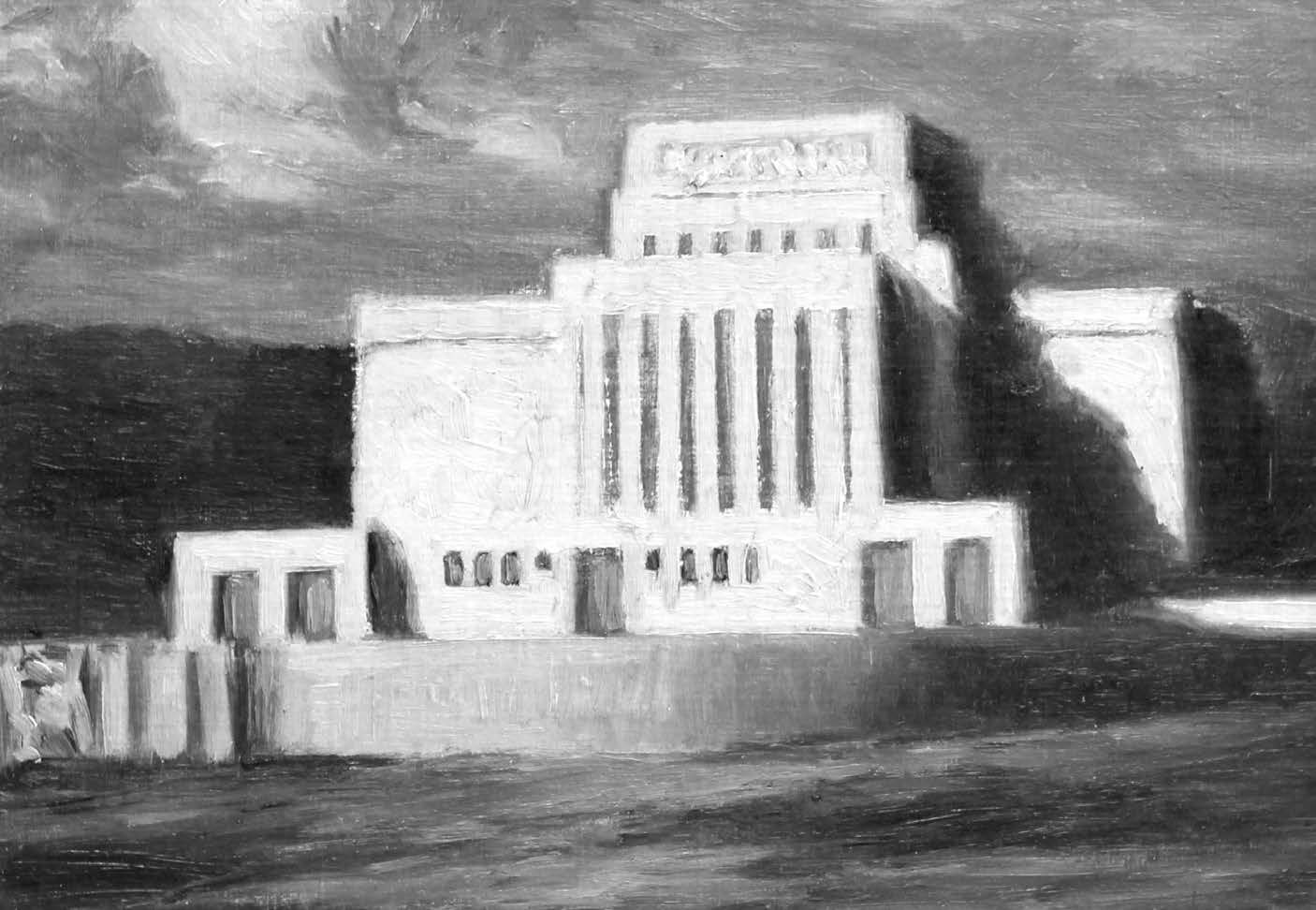

Since the early 1850s, Church members in Hawaiʻi have resided on the six principal islands: Kauaʻi, Oʻahu (with the temple), Molokaʻi, Maui, Lānaʻi, and Hawaiʻi (the Big Island). Since the temple’s dedication in 1919, individuals, families, and likely small informal groups had traveled from the “outer islands” to Oʻahu to attend the temple. However, in 1933 leaders and members on Molokaʻi organized what is likely the first formal outer-island temple trip. This practice became an annual event, was adopted on other islands, and became standard practice on all outer islands in the 1940s. Some semblance of this practice has been maintained to the present day.

Molokaʻi

Becaue of economic challenges and more job opportunities on other islands, Molokaʻi’s population had fallen to under fifteen hundred people by the turn of the twentieth century. Then in the early 1920s, with passage of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, families began to return as the government offered land for homesteading purposes. Some of these families were members of the Church, and by the early 1930s they had established a modest but closely knit group of Saints, many of whom were “temple members.”[35]

Molokaʻi member Henry Kaalikahi recalled that members who traveled to Oʻahu for business would at times take advantage of the opportunity to attend the temple and, upon return, would bear their testimonies of their experience. Such testimonies would stoke members’ desire for temple worship, and that desire led to the idea of forming a temple group. Arrangements were made throughout 1933, and eventually an excursion was set for Thanksgiving week because members saw temple work as a fitting way of showing their thanks to God.[36] With little money available, the approximately fifty members making the trip felt blessed to secure free passage to Honolulu and back on a barge transporting pineapples. Upon arrival in Honolulu, they received their temple recommends from the mission president, and then local members drove them to Lāʻie, where they spent more than a week doing temple work.[37]

In 1933 members on the island of Molokaʻi organized what is likely the first formal outer-island temple trip. It became an annual event, and by the 1940s the practice had become standard for all outer islands. Photo of Molokaʻi Saints in 1935 courtesy of Darlene Makaiwi.

In 1933 members on the island of Molokaʻi organized what is likely the first formal outer-island temple trip. It became an annual event, and by the 1940s the practice had become standard for all outer islands. Photo of Molokaʻi Saints in 1935 courtesy of Darlene Makaiwi.

Other islands

Annual Thanksgiving temple trips from Molokaʻi continued, and similar temple trips from the Big Island and Maui began as well. These temple trips were generally instigated by local leaders hoping to promote temple work among their members and served as a culmination of the genealogical work conducted throughout the year. Also welcome was the feeling of family formed among members making the trip together. Particularly helpful was the ability to defray costs as a group. Molokaʻi member Gary Adachi explained that because they raised funds, traveled, shopped, and cooked together, the cost to individual members or families was achievable and more were able to attend.[38] Some groups raised funds for these temple trips through bake sales, bazaars, and concession stands at community events. Others were able to collect donations such as beef, cabbage, and poi to help feed the group during the trip. “Because it was for church, the people were willing to donate,” said Samuel Alo. “I always tell them that the Akua [God] will bless them.”[39]

In Lāʻie these temple groups generally stayed at the Lanihuli house, the former mission home just north of the temple. The home had a large sitting and dining room area with individual rooms lining the sides. When temple groups exceeded Lanihuli’s capacity, local members readily welcomed them into their homes. Barbara Robinson of the Big Island recalled taking food with them, including half a cow, so when they stayed with members in Lāʻie, they could share their food.[40]

Temple trip traditions

Over the years traditions formed around these temple trips. The Sunday before the trip, the Molokaʻi Saints held a special meeting in which they shared their testimonies and asked forgiveness of each other. “There was such an outpouring of love for everyone in those meetings,” recalled Leda Kalilimoku. “Then we were all able to go to the temple with a singleness of purpose and pure in heart.” Recalling the bus ride from Honolulu over the Old Pali Road and along the coastline down to Lāʻie, Leda fondly remembered “singing songs, laughing joking, etc.” and enjoying a feeling of camaraderie.[41]

During their stay in the Lanihuli home, many temple groups held morning and evening devotionals, often called pule ʻohana or simply ʻohana (pule means “prayer,” ʻohana means “family”). Several Molokaʻi Saints recall John Kamahele Pawn walking up and down the hallway early in the morning ringing a bell and calling out, “ʻOhana, ʻohana!” Everyone gathered in the front room, sang a hymn, received instructions for the day, listened to a short inspirational talk, and read or recited scriptures. Then, after a prayer, most of the adults proceeded to the temple, while those assigned to remain that day oversaw the children and attended to cleaning, food preparation, and other chores.[42] As a child on such temple trips, Gail Kaapuni recalled, “It was an exciting time for us for we knew we’d be spending a whole week with friends from church. . . . It was like being on a weeklong camping trip.”[43]

Further, while temple groups were visiting Lāʻie, members of the community would gather with them almost every night to sing songs and entertain. “We would take whatever we had to share with them,” said Lāʻie community member Teresa Warner, and “at night [we would] sing and dance.”[44] Community and outer-island members often formed friendships, renewed annually through these temple trips.

Members making these temple trips would often take home as a keepsake the little slips of paper given them in the temple with the names of those for whom they had done the work, saving them in a special place. But that was not all they would take home. As Gail Kaapuni explained, “When my parents returned, there was always a different atmosphere in the home for several weeks. My parents seemed happier and spoke to each other in softer tones. My Dad smiled more, and his general demeanor was gentler. My Mom could be heard humming while she baked or cooked. . . . Yes, there was a definite change in the family atmosphere after a temple excursion week. Seeing my parents get so excited about temple week in Laie became a model of what I wanted in my adult life.”[45]

An Outpost to Other Nations

Because Hawaiʻi had become incredibly cosmopolitan through decades of labor immigration, a more concerted effort to share the gospel with these various ethnicities had begun during the mission presidency of E. Wesley Smith in 1919. At the conclusion of his mission in 1923, President Smith reported that with growing “membership among the Chinese, Philippine and Japanese population,” he now considered the Hawaiian Mission a logical location from which to take missionary work to Asia.[46]

Some years later, mission president Castle Murphy was concerned that certain members did not understand English well enough to fully benefit from their experience at church so in 1932 he organized Chinese, Japanese, and Samoan Church groups and called members from among them “as missionaries to labor among their people using [their] . . . language so those people would feel comfortable in meetings.”[47] A few years later, while organizing the first stake in Hawaiʻi in 1935, President Heber J. Grant observed these groups and determined: “Here we will organize a mission. . . . In Hawaii we will train young people and send them to preach to their own people and they will listen to them.”[48] Shortly thereafter, Hilton H. Robertson and his wife Hazel were called to set up the Japanese Mission in Hawaiʻi (later renamed the Central Pacific Mission).[49] Now there were two missions in Hawai‘i, both headquartered in Honolulu, one working among Hawai‘i’s large Japanese population and the other continuing to serve the general population.

J. Reuben Clark, First Counselor in the First Presidency, accompanied President Grant on that visit to Hawaiʻi in 1935 and reported: “It would seem not improbable that Hawaii is the most favorable place for the Church to make its next effort to preach the Gospel to the Japanese, [Chinese, Filipinos, and Indians].” He noted that “Hawaii is the gateway to all of our branches in the widely scattered islands of the Pacific.” Then President Clark added:

Furthermore, the Temple at Laie stretches out its sanctifying welcome not only to that great group of descendants of Lehi in the Pacific, but also and equally to all others. . . . And who can estimate or measure the unifying influence of the inspiration and fortifying spiritual power of this little Temple at Laie, and the glorious work for the salvation of the millions and millions who have gone before, carried on within its walls, as it rests there in the midst of the mighty waters of the Pacific.

In this view the Hawaiian Islands are indeed the outpost of a great forward march for Christianity and the Church, among those mighty peoples that face us along the eastern edge of our sister hemisphere.[50]

For over eighty years the Hawaiian Saints had been connected with the house of Israel—particularly through the tribe of Joseph and its obligation to gather other nations—and having a temple in their midst was proving providential in their ability to do so.

A Succession of Temple Presidents

President Waddoups’s release and further contribution

Seven months after President Grant’s visit, President Waddoups received a letter from the First Presidency releasing him as temple president and plantation manager and calling him “as president of the Samoan Mission for one year . . . as a special genealogical researcher and organizer to the Polynesian Mission.”[51] In the year and a half that followed, the Waddoupses helped organize genealogy work and gathered thousands of names in both Samoa and New Zealand, and these names flowed to the Hawaii Temple.[52]

![Extolling the strong Asian presence within the Church in Hawaiʻi, Elder J. Reuben Clark Jr. considered the Hawaiian Islands “the outpost of a great forward march [of] the Church” into Asia. Photo of Heber J. Grant and J. Reuben Clark Jr. courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of Japanese Saints in Hawaiʻi courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/6838/Laie_Hawaii_Temple_August_7_Page_243_Image_0001.jpg)

![Extolling the strong Asian presence within the Church in Hawaiʻi, Elder J. Reuben Clark Jr. considered the Hawaiian Islands “the outpost of a great forward march [of] the Church” into Asia. Photo of Heber J. Grant and J. Reuben Clark Jr. courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of Japanese Saints in Hawaiʻi courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/6838/Laie_Hawaii_Temple_August_7_Page_243_Image_0002.jpg) Extolling the strong Asian presence within the Church in Hawaiʻi, Elder J. Reuben Clark Jr. considered the Hawaiian Islands “the outpost of a great forward march [of] the Church” into Asia. Photo of Heber J. Grant and J. Reuben Clark Jr. courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of Japanese Saints in Hawaiʻi courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Extolling the strong Asian presence within the Church in Hawaiʻi, Elder J. Reuben Clark Jr. considered the Hawaiian Islands “the outpost of a great forward march [of] the Church” into Asia. Photo of Heber J. Grant and J. Reuben Clark Jr. courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of Japanese Saints in Hawaiʻi courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Upon his return to Utah, Waddoups was appointed supervisor of genealogical and temple work in all Polynesian missions, and he began work at the Genealogical Society of Utah, where he established a Polynesian department.[53] During this time, Waddoups won approval for his petition that the entire Hawaiian people be treated as their own “family,” thus allowing temple work to be done for early generations without requiring those submitting names to show direct familial connections.[54] This was likely among the first, if not the first, exception for an entire people, and it almost instantly permitted temple work to be done for thousands of more names. Emboldened, Waddoups asked that each Polynesian mission also be given the same exception, and approval was given to the people of Tahiti, Samoa, Tonga, and New Zealand as well.[55]

In 1941 the Waddoupses accepted a job in Honolulu, and seven days after their arrival, Apostle David O. McKay set apart Waddoups as second counselor in the temple presidency to his old friend Albert H. Belliston.[56] Waddoups served in this position for two and a half years before accepting the governmental appointment as superintendent of the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement. Three and a half years later, Waddoups returned to Utah, resuming his work as director of the Genealogical Society’s Polynesian department. When setting the Waddoupses apart as temple workers in the Salt Lake Temple, Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith placed on them a “responsibility of looking after the genealogical and temple interest of the people of the Polynesian missions.”[57] This they did until Waddoups’s passing in 1956.

It is striking in hindsight to consider the mere moment of prompting that led President Joseph F. Smith to change twenty-one-year-old William Waddoups’s calling to serve a mission in Colorado to serving in Hawaiʻi. That decision has had enormous consequences on temple work in Polynesia. Add Waddoups’s years as a missionary (four), at Iosepa (eleven), as president of the Laie Hawaii Temple (sixteen, simultaneously serving as mission president, then plantation manager for eight of those sixteen years), as Samoan Mission president with a special genealogy assignment (one and a half), as second counselor in the temple presidency (two and a half), and as superintendent of Kalaupapa (three and a half) to his years directing the work of Polynesian genealogy in Salt Lake City (twelve) and all together this equals more than fifty years of service to the people of Polynesia—a people whom he revered. For all who work in the Laie Hawaii Temple, President William Mark Waddoups has provided a powerful legacy of quiet leadership and faith.

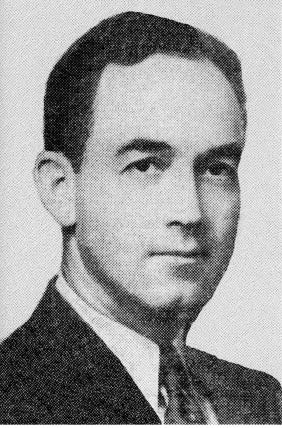

Edward and Irene Clissold, 1936–1938

All were surprised by President Waddoups’s release in 1936 and the accompanying directive to turn the temple and plantation over to stake authorities.[58] The stake had been formed just eight months earlier with Ralph E. Woolley, who had supervised the temple’s construction, as its president. In May, just before the Waddoupses’ departure, President Woolley called his first counselor, Edward LaVaun Clissold, to his office and presented him a letter from the First Presidency calling Clissold to preside over the Hawaii Temple. “I felt greatly honored,” wrote Clissold, but “hardly equal to this responsibility.”[59] He began presiding when Waddoups departed. So quick was the transition that it wasn’t until months later that Clissold and his wife Irene traveled to Salt Lake City and were officially set apart as president and matron of the Hawaii Temple by President Grant, with Elder David O. McKay assisting.[60]

After sixteen years of service as temple president and matron, William and Olivia Waddoups were released. Their lives would remain intertwined with temple work in Polynesia until their passing. Courtesy of Stephen Kelsey.

After sixteen years of service as temple president and matron, William and Olivia Waddoups were released. Their lives would remain intertwined with temple work in Polynesia until their passing. Courtesy of Stephen Kelsey.

Barely thirty-eight years old, Clissold remains among the youngest to ever fill the position of temple president. However, Clissold was no stranger to the Hawaii Temple. After service in the US Navy as a young man, he was called on a mission to Hawaiʻi in 1921. His second assignment was to serve in the temple under President Waddoups, where he learned all the parts of the ceremony and experienced the temple’s procedures. “That service,” wrote Clissold, “created in me a love for temple work, which has persisted through the years.”[61]

Though not without experience, President Clissold felt a nagging fear of inadequacy toward his new calling.[62] Then one afternoon as he was walking through the celestial room, he experienced a strong manifestation that the mantle of president had passed from Brother Waddoups to himself, and he concluded that “it was just a matter of learning and applying myself, but the fear left.”[63] He later shared, “I spent many hours alone in the sacred building studying and reading all the written accounts I could find of the institution of Temple work in this dispensation. I found these periods of study and prayer richly profitable and look back on them now as some of the sweetest hours I have ever spent.”[64]

With the rather sudden departure of the Waddoupses, Edward L. Clissold (first counselor in the newly formed Oʻahu Stake presidency) was called on to fill the assignment of temple president. This was the first of three times that he would serve as

With the rather sudden departure of the Waddoupses, Edward L. Clissold (first counselor in the newly formed Oʻahu Stake presidency) was called on to fill the assignment of temple president. This was the first of three times that he would serve as

the Hawaii Temple president. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Remarkably, President Clissold retained his stake duties, lived in Honolulu with his young family (thirty-five miles from the temple—more than an hour’s drive), and continued building a new business all while fulfilling his calling as temple president. And like President Waddoups, President Clissold served without counselors. Yet at the end of the year, he and stake leaders “were immensely pleased with the record at the Temple.”[65] To this success Clissold gave credit to the exceptional people “laboring in the Temple who were diligent in their labors and gave great support.”[66]

The letter to Clissold from the First Presidency asked him to serve for a year; he served almost two (May 1936 to January 1938). The rather impromptu calling of President Clissold was somewhat unique, and his tenure was comparatively short. However, this was only the first of three times that he would serve as the Hawaii Temple president (again in the 1940s and 1960s). During this first period of service, there were generally three temple sessions during the week, and occasionally one on Saturday morning as well.[67] However, President Clissold felt that it was just a matter of time until the temple sessions would increase and a full-time president would be necessary.[68] This change occurred in January 1938 with the appointment of Castle H. Murphy.

Castle and Verna Murphy, 1938–1941

As a young man, Castle Murphy was engaged to Verna Ann Fowler when he received a call to serve a mission in Samoa. When Church authorities learned of the engagement, they changed the call to Hawaiʻi and called Verna there as well. (Sister missionaries were not called to Samoa in those days.) Castle and Verna soon married in the Salt Lake Temple and left on their missions to Hawaiʻi together. After serving successfully for four years from 1909 to 1913, they returned home with a deep love for Hawaiʻi, stronger testimonies, the ability to speak fluent Hawaiian, no money, and two children. They returned to Hawaiʻi from 1930 to 1936 as mission president, which included brief service as temple president from 1930 to 1931. Then in 1938, the Murphys, now in their early fifties, returned to Hawaiʻi to serve exclusively as temple president and matron.[69]

The Murphys took pride in training members of varied nationalities to perform the parts, ceremonies, and ordinances of the temple, noting that at times “companies were served by natives alone, with the Temple President and Temple Matron supervising only.”[70]

An experience that emboldened President Murphy in his work came one night in a dream:

I dreamed that I was in the temple when I heard a great cry from the outside. I rushed to the door and looked out to see a great concourse of people moving toward the temple, apparently in great fear. The sky above them was nearly black as though a terrible storm were about to destroy everything in its path. I called out to the people . . . and asked what was coming.

To this they replied, “We fear that we are all to be destroyed unless you permit us to come into the temple. It is the only way in which we may be saved.”

I said, “I cannot permit you to enter this sacred building, for [you] are not yet prepared to do so.”

I was filled with fear for them. I bowed my head and began to pray that they might in some way be spared until we could do something to prepare them so that they might be worthy to enter and be saved.

At that I awakened. . . . I rather thought that [the dream] came as a warning to me to do all in my power to persuade the people to prepare without delay to receive the blessings which await them in the temple.[71]

Temple workers, circa 1938–41. Temple president Castle Murphy (seated fourth from left) and his wife Verna (directly behind him) took pride in training members of varied nationalities to perform the parts, ceremonies, and ordinances of the temple, noting that at times “companies were served by natives alone.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Temple workers, circa 1938–41. Temple president Castle Murphy (seated fourth from left) and his wife Verna (directly behind him) took pride in training members of varied nationalities to perform the parts, ceremonies, and ordinances of the temple, noting that at times “companies were served by natives alone.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

During their service, the Murphys welcomed several groups of members from other islands who came to do temple work and cherished the experiences they shared with them. Of one occasion President Murphy wrote: “After performing sealings all day and seeing the coverlets of the sealing room altars wet with tears of joy as they flowed from the eyes of those lovely, faithful people, I would return to my bed at home and, although voice weary and physically worn, my heart swelled with gratitude unto the Lord for the blessed privilege which had been mine.”[72]

Concluding his thoughts of their service in the temple, President Murphy said, “Sister Murphy and I have come to love the people of Hawaii so much that we can only hope that our lives may merit a continuation of association with them in eternity.”[73]

Temple Renovation in 1938

The temple was approaching twenty years since its construction and had endured the near-constant wind, salt, and humidity of its windward coast location. Thus in 1938 a thorough refurbishing, including the addition of modern equipment and conveniences, was conducted throughout the temple.[74] During this time, LeConte Stewart, the original painter and decorator of the temple, returned to supervise the choosing of new drapes and furnishings. He would return again with his family two years later to refurbish the murals.[75]

Success of the Bureau of Information (visitors’ center) warranted an enlarged facility, and in 1938 it was more than tripled in size. Photo of bureau and temple courtesy of Mark James.

Success of the Bureau of Information (visitors’ center) warranted an enlarged facility, and in 1938 it was more than tripled in size. Photo of bureau and temple courtesy of Mark James.

But the temple itself was not the sole recipient of attention in 1938. Success of the Bureau of Information (the visitors’ center) warranted an enlarged facility.[76] Architect Harold W. Burton joined with Ralph E. Woolley as they had in the temple’s construction. Burton designed additions to the Bureau, and Woolley was superintendent of construction.[77] Further, Avard Fairbanks returned to reproduce on a small scale the famous friezes that adorn the top of the temple for the walls of the Bureau’s lecture room. These reproductions enabled missionary guides to comfortably teach visitors of the four scriptural eras, underscoring the Book of Mormon, the Restoration, and the purpose of temples.[78]

Twentieth Anniversary of the Temple

The 1930s ended with a celebration commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the Hawaii Temple. On its front page the Honolulu Advertiser newspaper announced: “One of the great religious centers of this part of the world will be the scene of . . . Polynesian pageantry as Latter Day Saints of Oahu gather at Laie tomorrow to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the dedication of the world-famous Mormon Temple at Laie.”[79]

The building had become an icon and brought esteem to the Church. Such honor was welcome, though comparatively incidental to the blessings it had afforded individuals and families for twenty years on both sides of the veil.

Notes

[1] “Sugar has been the economic mainstay of Laie. It has produced revenues which not only met the needs of Laie but made possible the construction of early chapels and other missionary facilities throughout Hawaii.” David W. Cummings, Centennial History of Laie: 1865–1965 (Lāʻie, HI: Laie Centennial Committee, 1965).

[2] See Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, 2011), 133–34.

[3] Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 10 August 1928.

[4] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 1 January 1922.

[5] “Many of the people in the village, disheartened by the slump, moved away. This was reflected in the Temple. All daytime sessions were discontinued and only two night session weekly remained.” Cummings, Centennial History of Laie. Waddoups mentions increasing the number of temple sessions from one to two per week in a letter to John Adams, 16 January 1932, Riley Moffat files, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[6] William M. Waddoups, “Personal History of William Mark Waddoups,” 6, William M. Waddoups Papers, 1883–1969, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[7] William Waddoups to Antoine Ivins, 7 May 1931, Riley M. Moffat files, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[8] After ten years as Lāʻie Plantation manager (1921–31), Antoine R. Ivins was called to preside over the Mexican Mission, and shortly thereafter he was set apart as a member of the First Council of the Seventy. Under his direction, the temple ceremonies were translated into Spanish in what was likely the first complete translation of the temple ceremonies into a foreign language.

[9] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6. Between 1925 and 1935, three of ten operating sugarcane plantations in Hawaiʻi would close, and their land was either leased or sold to larger operations. The Lāʻie Plantation was one of them. See also William H. Dorrance and Francis S. Morgan, Sugar Islands: The 165-Year Story of Sugar in Hawaii (Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 2001), 41.

[10] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 8 August 1931.

[11] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[12] “As the two assignments were difficult to correlate, we were released as temple president and matron July 27, 1931.” Castle Murphy, Hui Lau Lima News, 24 November 1957.

[13] William Waddoups to Eugene Neff, 21 January 1932, Riley M. Moffat files, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[14] William Waddoups to Antoine Ivins, 4 April 1932, Riley M. Moffat files, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[15] Jeffrey Stover, “The Legacy of the 1848 Māhele and Kuleana Act of 1850: A Case Study of the Lāʻie Wai and Lāʻie Maloʻo Ahupuaʻa, 1846–1930” (master’s thesis, University of Hawaiʻi, 1997), 98.

[16] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[17] Waddoups to Adams, 6 December 1932.

[18] Of conditions in Lāʻie during the Great Depression, Vaitaʻi Tanoaʻi Tuala Reed stated, “We were very poor, so I had to quit school, and I had to go and work at Kahuku Plantation. I pulled the dried leaves around the cane. I think I got 10 cents an hour.” “Talk Story,” Kaleo o Koʻolauloa (a newspaper distributed by Hawaii Reserves Inc. for about ten years in the communities of Lāʻie, Kahuku, and Hauʻula).

[19] “I am trying to encourage the people here to do more farming and gardening. To raise more and better chickens and ducks, to have a cow [etc.].” Waddoups to Adams, 16 January 1932. See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, chapter 7.

[20] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[21] See Honolulu Advertiser, 4 April 1930, 6. An entire twelve-page section was dedicated to the Church in the paper’s Sunday morning edition, 6 April 1930.

[22] Olivia Sessions Waddoups, journal, 31 March 1930, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[23] See Waddoups, journal, 9 April 1930. The temple was generally closed during the actual conference; however, numerous members (many of whom had traveled from outer islands) would stay the following week and do temple work.

[24] Amoe Myers, interview, 19 February 1985. Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, OH-264, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 11–12.

[25] Myers, interview, 11–12.

[26] Waddoups to Ivins, 4 April 1932.

[27] Waddoups to Adams, 6 December 1932.

[28] See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 74.

[29] Castle Murphy, “Hawaiian Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 10 October 1933, 211–12.

[30] See Murphy, “Hawaiian Mission,” 211–12. This effort was not confined to the Hawaiian Islands. Also, in 1932 New Zealand Mission president Harold T. Christensen “organized the first Mission Genealogical Committee, setting apart Stuart Meha as its president on 15 Dec. 1932. Meha and his wife, Ivory (Ivy), had been called to spend time at the Hawaii Temple learning genealogical work, policies, and procedures.” Marjorie Newton, Tiki and Temple: The Mormon Mission in New Zealand, 1854–1858 (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2012), 195–96.

[31] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 7 June 1932.

[32] Murphy, “Hawaiian Mission,” 211–12.

[33] At that time there was a practice of calling members as “temple missionaries.” This policy ended in 1935, three years after Albert Like was set apart. “Council of the Twelve unanimously decided that members should not formally be called on temple missions, however, they should be encouraged, persuaded and advised to perform temple work.” “Policy Statements from Board Minutes,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, 5 February 1935, 109.

[34] Albert Nawahi Like, interview, OH-149, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 16–17.

[35] See William Kauaiwiulaokalani Wallace III, “LDS Homesteaders: Hoolehua 1923–1926,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 2, no. 1 (1981), https://

[36] See Henry Kaalikahi, “History of Molokai Temple Group,” in William Kaleimomi o Hoʻolehua Wallace Jr., “Moʻolelo Kahiko,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 13, no. 1 (1992): 42–43, https://

[37] See Molokai District general minutes, 26 November 1933 and 5 December 1933, CHL. See also Mary T. Kim, interview, OH-465, Molokai Temple Excursion, 26 November 1980, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[38] Gary Adachi, interview, OH-465, Molokai Temple Excursion, 26 November 1980.

[39] Samuel Alo, “Alo ʻOhana Reunion Malaekahana, Oʻahu,” ed. Kaina Daines (unpublished manuscript, 2009), Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[40] See Sister Barbara Robinson and Sister Keliikoa, “The Church in Waimea,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 22, no. 1 (2001): 65, available at https://

[41] Leda Kalilimoku, OH-465, Molokai Temple Excursion, 26 November 1980.

[42] Kalilimoku, Molokai Temple Excursion, 26 November 1980.

[43] Gail Kaapuni, email message to Clinton D. Christensen, 24 April 2017.

[44] Teresa O. Warner (Nona), interview by Fred Woods, 26 July 2006, in authors’ possession.

[45] Kaapuni, email message.

[46] “The following article was published in the Deseret News of this date: ‘Islands Declared Logical Place to Train Missionaries.’” History of the Hawaiian Mission, 25 May 1923.

[47] Castle Murphy, “A Condensed History of an Era of Forty Years Progress in The LDS Hawaiian Mission with Authenticating Pictures and Related Items of Personal Involvement,” BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[48] Murphy, “Condensed History.”

[49] See R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, BYU–Hawaii, 2018), 279–300.

[50] J. Reuben Clark Jr., “The Outpost in Mid-Pacific,” Improvement Era, September 1935, 530–35.

[51] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[52] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[53] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 8.

[54] Presenting to the temple committee, Elder Widtsoe gave voice to President Waddoups’s request this way: “‘Would it be proper to treat the entire people as one family, and permit them to do temple work for Hawaiians of early generations without requiring them first to make permanent connections? If this could be done, many thousands of names would be available for temple work in the Hawaiian Temple.’ The Board will recommend the suspension of the ordinary rule restricting members in their . . . own lineage for Hawaiians.” “Policy Statements from Board Minutes,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, 28 February 1939, 116.

[55] “Letter from Wm. M. Waddoups read recommending that for each of the Polynesian mission as a common heir be selected at whose instance temple ordinances could be performed. The Board agreed to appoint a committee to determine heirs for Hawaii, Tahiti, Samoa, Tonga, and New Zealand.” “Policy Statements from Board Minutes,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, 12 April 1939, 123.

[56] As young missionaries in Hawaiʻi, William Waddoups and Albert Belliston had served together, and each highly regarded the other. Waddoups wrote of Belliston, “He proved to be one of the best and most helpful companions and friend I ever had. He is a man of real character, full of integrity, patience and faith.” See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 3.

[57] Waddoups, “Personal History,” 8.

[58] See Edward L. Clissold, journal excerpts, 1936–38, in family possession.

[59] Clissold, journal excerpts. A letter was also sent to Frank Woolley (brother of Ralph and son of Samuel E. Woolley) calling him to be the plantation manager.

[60] “I took over my duties upon his departure but was not yet set apart as Temple President until I could go to Salt Lake City in August of that year.” Edward L. Clissold, “Hawaiian Temple,” Hui Lau Lima News, 24 November 1957.

[61] Edward L. Clissold, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 11 June 1956, MSSH 261, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[62] See Edward L. Clissold, interview by Kenneth Baldridge, 1980 and 1982, OH-103, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 3.

[63] Clissold, interview by Baldridge, 3.

[64] Clissold, “Hawaiian Temple.”

[65] Clissold, journal excerpts.

[66] Clissold, “Hawaiian Temple.”

[67] See Clissold, interview, 1.

[68] See Clissold, interview, 4.

[69] See Murphy, “Condensed History.”

[70] Castle H. Murphy, Hui Lau Lima News, 24 November 1957.

[71] Castle H. Murphy, Castle of Zion: Hawaii (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1963), 50–51.

[72] Murphy, Hui Lau Lima News.

[73] Murphy, Hui Lau Lima News.

[74] See Ka Elele o Hawaii Presents the Hawaiian Mission in Review (Hawaiian Mission newsletter, 1942), 49.

[75] See Zipporah L. Stewart, Hawaiian Temple reminiscence, 27 February 1978, MS 6124, 7, CHL.

[76] See Ka Elele o Hawaii, 49.

[77] See Harold W. Burton, “Hawaiian Temple,” in N. B. Lundwall, Temples of the Most High (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1975), 151–53.

[78] See Ka Elele o Hawaii, 49.

[79] “Mormons hold Fete at Laie Tomorrow,” Honolulu Advertiser, 26 November 1939, 1. Among the speakers were Ralph E. Woolley, temple contractor and stake president; Robert Plunkett, temple recorder; and Castle Murphy, temple president. The Samoan and the Hawaiian chorus provided music.