Establishing the Work—1920s

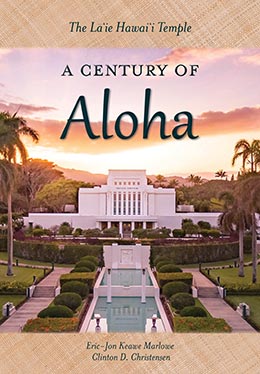

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Establishing the Work—1920s," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 161–182.

Aerial view of the Church colony of Lāʻie, Oʻahu, circa 1923. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Aerial view of the Church colony of Lāʻie, Oʻahu, circa 1923. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

First Ordinances Performed

A fair number of members who traveled to the temple dedication remained in Lāʻie to do temple work, and on Monday, 1 December 1919, the temple processed several of their records.[1] On Tuesday the temple doors opened for the first time for patrons to perform baptisms for the dead. Mary Ann “Mele” Wong Soong, age nine at the time, recalled, “I did baptism for the dead for two days. I stayed in the font so long that my fingers and toes became wrinkled. They had to pump warm water into the font. . . . This was my first experience in the temple.—[It] was so beautiful.”[2] At that time any baptized member, including Primary children, could do baptisms for the dead, a practice that continued until the minimum age of twelve became standard in 1960.[3]

Hawaiian member Lydia Kahōkūhealani Colburn had submitted the name of her sister Carry, who had died just over a year earlier, and was able to witness her sister’s proxy baptism. Following this experience, Lydia recorded:

A few nights after that, I dreamed. It seemed as if . . . we were [in the train depot] going again to Laie. As I was sitting with my bags and with my family, I . . . recognized two girls standing at the window, where tickets were sold. As I looked I noticed that one of these girls was my sister . . . , her baptism being completed. . . . I called, “Carry, Carry,” and in calling I began to cry. She came and she was a beautiful woman. She said, “Sister, don’t cry. Don’t you know I am about my Father’s business now.” . . . I was startled and awake. I meditated, surely, she had been in prison, and at this time she was out. There were two of them. Apparently they were going on a mission. There is life . . . on that side. Death is not to be feared.[4]

On Wednesday the first endowments were performed. The lone session with thirty-six participants started at 9:00 a.m. and did not conclude until nearly 5:00 p.m.[5] “We got out about dark, tired and hungry,” recorded Elder Ford Clark, “but it is a great work.”[6] Eight hours (without lunch) for an endowment session was long in comparison with an endowment session today. However, as a first-time experience for most, the session began with considerable instruction to participants in the temple chapel, and the initiatory was then conducted in concurrence with the endowment (the separation of which would not begin until the 1960s),[7] and all was done using mostly first-time workers (generally young missionaries).

Having long anticipated the special day, “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi attended the temple shortly after its dedication. Upon returning to her home in Honolulu, she took ill and passed away the following week. “She had been to the Temple, a thing for which she had lived.” Photo by Monique Saenz. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Having long anticipated the special day, “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi attended the temple shortly after its dedication. Upon returning to her home in Honolulu, she took ill and passed away the following week. “She had been to the Temple, a thing for which she had lived.” Photo by Monique Saenz. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Thursday’s endowment session was two hours shorter, and among the fourteen individuals endowed on Friday, 5 December, was “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi, who President Joseph F. Smith had promised would live to attend the temple.[8] Elder Ford Clark recorded, “Worked in the Temple again. Old Sis Ma was one of them. Newman and I had to carry her thru. When she came out she said she had seen Joseph F. Smith’s face and he said ‘aloha’ to her. Also in one of the rooms a dove flew in thru the window and sat on the end of her bench.”[9] Ma Manuhiʻi was also sealed to her husband that day. Thereafter Ma returned to her home in Honolulu, took ill, and passed away the following Friday. “She had been to the Temple, a thing for which she had lived,” reported Elder Wilford King, “and she was ready to return to her Maker.”[10]

Sensibly, President Lund remained in Lāʻie the week following the dedication and observed the first few endowment sessions.[11] In addition to his calling as First Counselor in the First Presidency, President Lund was simultaneously serving as president of the Salt Lake Temple (1911–21). Formation of a formal temple department at Church headquarters was decades away, and since the Salt Lake Temple’s dedication, the Salt Lake Temple president was a member of either the First Presidency or Quorum of the Twelve. Consequently, the Salt Lake Temple had become a source of guidance for all other temples. Thus President Lund’s supervision of initial ordinance work in the Hawaii Temple offered valued assurance to all involved that the work they were performing was acceptable.

By the end of the second week, President Waddoups noted, “The work is now being done in very good order. We were all finished [with endowments] about 1:30 p.m.”[12] Within the first few months of the temple’s opening, ordinance work therein settled into a predictable schedule, with baptisms on Tuesday and endowment sessions Wednesday through Friday (one each day, from 9:00 a.m. until early afternoon).[13] Within the first couple of years, more daytime and several night sessions were added,[14] and special sessions were often created for mission conferences and to accommodate groups traveling from afar.

Temple Missionaries

At first temple workers were generally full-time missionaries from Utah assigned by the mission president to work in the temple under President Waddoups’s direction.[15] There were practical reasons for this. First, such work occupied most of the day, and most Hawaiian members needed to provide for themselves and their families.[16] Second, those called to serve as temple missionaries had at least some temple experience. However, not long after the dedication a number of Hawaiian full-time missionaries were also assigned to serve in the temple. Elder E. Paul Kaulana Elia recalled: “I was sent down Laie to work in the temple. . . . I didn’t know anything about temple work. And so when I went over there . . . , we had to go and study these ordinances, performing or representing the different parts in there.”[17] Further, missionaries assigned to the temple generally had dual assignments, with the second assignment involving working on the plantation, staffing the Bureau of Information, proselyting nearby, or assisting with the community school.[18]

Translation of Temple Ceremony

Within the early months of the temple’s opening, President Waddoups translated at least portions of the temple ceremony into Hawaiian.[19] Although many Hawaiians understood and spoke a measure of English, several of the older generation stood to benefit from a Hawaiian translation. Records indicate that during the years of the Iosepa colony in Utah, Joseph F. Smith, and assumedly others, accompanied individual Hawaiian members through the Salt Lake Temple, translating the ceremony for them.[20] However, Waddoups’s translation appears to have been used at times in the actual presentation of temple ceremonies, which was likely a first within latter-day temples.

Genealogy of King Kamehameha

Using the recently published work of ethnologist Dr. Abraham Fornander, temple recorder Duncan McAllister was able to arrange the genealogy of King Kamehameha. One month after the temple opened, President Waddoups noted: “We performed the ordinances for the Royal line from which King Kamehameha is supposed to have sprung. . . . I feel it quite an honor.”[21]

Temple workers initially were full-time missionaries assigned to work in the temple, a responsibility soon shared by community members willing and able to commit the considerable hours needed to do so. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Temple workers initially were full-time missionaries assigned to work in the temple, a responsibility soon shared by community members willing and able to commit the considerable hours needed to do so. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Considering the timely circumstances under which Fornander’s foremost collection of legends, chants, and genealogies related to ancient Hawaiians was published in 1919, the same year as the temple’s dedication, Susa Young Gates (daughter of Brigham Young and former missionary to Hawaiʻi) declared: “How strange are the hand dealings of the Lord! For twenty years this Hawaiian genealogist and antiquarian [Dr. Abraham Fornander] has been at work on the preparation of this book; and now, with the completion . . . of the Hawaiian temple, comes this publication. . . . ‘God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform.’”[22]

Forced Temple Closure

The 1918 flu pandemic roiled for a couple of years, tragically peaking in Hawaiʻi in 1920.[23] The Waddoups family did not escape its fearful reach—their eleven-year-old daughter, Wilda, was among those stricken, and she passed away on 25 March 1920.[24] Unimaginably, Wilda was the third child the family had lost in ten years. Later President Waddoups would say, “We have been blessed with six lovely children. God has seen fit to take three of them home to Him. We know if we serve him well we will have them all in eternity.”[25]

The temple closed the first week of April 1920 so the sick could be cared for. Circumstances improved enough the following week that the temple reopened and resumed operation according to its usual schedule.[26] Although less deadly than the 1920 outbreak, another severe epidemic of typhoid and influenza would cause the temple to close again in the fall of 1921.[27]

Appointment of Temple Assistants

Unlike temple presidents today, President Waddoups essentially functioned without counselors. Documents suggest that in the first twenty-two years, only one counselor to the Laie Hawaii Temple president (for a duration of two years) was officially set apart.[28] Furthermore, practice in other temples at that time suggests that the role of temple “matron,” and its fulfillment by the temple president’s spouse, was not yet a standard practice.[29] Although Olivia Waddoups loved the temple and assisted whenever she could, her first priority was her children.[30] So it was with perhaps a degree of relief that the Waddoupses welcomed missionaries George and Christina Bowles, who arrived in Lāʻie from Utah on 5 May 1920 with an “appointment, to work in the Temple.”[31] The Bowleses were technically under the administration of the mission president; however, records often refer to them as “temple assistants.” But this was not all; the Bowleses came with valuable experience since George had served as mission president in New Zealand (1909–11). Their experience would be invaluable to a high-water mark of temple activity in 1920: the arrival of the first temple group from New Zealand (see chapter 12 herein).[32]

Temple Funding and Maintenance

Well into the twentieth century, at least part of the cost of maintaining a temple was considered the responsibility of members who used that temple. Policy in place since the opening of the Salt Lake Temple read: “All who come to the Temple to perform ordinance work are expected to make donations, according to their circumstances, to aid in meeting necessary expenses; but the poor who have nothing to give are equally welcome.”[33]

Records of patrons making such donations to the Hawaii Temple are not readily apparent; however, funds for temple expenses were garnered in other ways. A typical Saturday entry in President Waddoups’s journal records: “I spent part of today working with Marr [his nine-year-old son] in the Temple Grounds cleaning up weeds. In afternoon I sold ice cream for the benefit of Temple. Took charge of picture show in the evening the proceeds to go to Temple Fund.”[34] Over the years other creative means of raising funds for the temple would follow.[35]

Housing for Temple Workers and Patrons

Traveling to the temple from afar necessitated the lodging of some patrons, yet Lāʻie had no public boarding options. President Waddoups had raised this concern, and two months after the temple dedication he received a letter from the First Presidency authorizing the building of “proper housing of those who come to work in the Temple.”[36]

Construction began almost immediately, and roughly five months later the furnishings were purchased for what was initially called the “community house.”[37] This building became part of a three-building complex that provided lodging for temple workers and patrons. The centerpiece of the complex (only a few hundred yards north of the temple) was the old Lanihuli mission home vacated when the mission headquarters was moved to Honolulu just months before the temple’s dedication.[38] The community house was built on the temple side of Lanihuli, and an almost identical house was built on the other side of the road (toward the ocean) for the temple president and his family. The completed complex accommodated about twelve visiting families for temple work,[39] the elders assigned to the temple (lodged in the community house), the sisters assigned to the community school and temple (in the two-story Lanihuli home), and the Waddoups family (in the temple president’s home).[40]

Yet a common form of lodging for those attending the temple in the first decades after its dedication was the homes of local members. As Church headquarters in Hawaiʻi for more than fifty years before the temple’s dedication, Lāʻie had long opened its doors to fellow members for mission conferences and other special gatherings—it was just part of living in Lāʻie. And with little or no prompting, the same openness was frequently extended to those attending the temple. Although lodging with local members while attending the temple slowly declined over the years, it revived whenever large excursions exceeded temple housing capacity, thus remaining a beautiful vestige of the Zion-like society that Lāʻie has always sought to become.

Early Temple Administration

Following the practice of temples in Utah, the Hawaii Temple closed during September. This gave President Waddoups and his workers a chance to visit various parts of the islands and do missionary work and help with members’ genealogy, a tradition President Waddoups would continue during the temple’s scheduled closings in years to come.[41] Not long after the temple’s reopening in October 1920, temple recorder Duncan McAllister and his daughter Katie were honorably released. McAllister had been called in large measure to ensure that the new temple, so far away from the center of the Church, met and maintained the high standards of a house of the Lord. His departure within a year of the temple’s dedication signaled his and Church leaders’ confidence that such a standard was being met and would continue to be met.[42]

McAllister’s Hawaiian protégé, Robert Plunkett Jr.,[43] was chosen as the new temple recorder, a position he would hold for twenty-eight years, serving with five temple presidents. Born and raised in Hawaiʻi, Robert and his wife, Julia Keikioewa Ku Plunkett, had been living in Salt Lake City for five years when President Grant called them to return to Hawaiʻi and serve in the temple. Brother Plunkett believed this call fulfilled a promise in his patriarchal blessing that he would one day return to his people and labor for their salvation.[44]

President William Waddoups actively served in many capacities in the temple’s early years. Beyond providing organizational leadership, he worked perhaps every temple session, assisting with the main ordinances and even covering multiple roles during the endowment when other workers were absent. His journal describes him filling such roles as temple janitor, handyman, landscaper, and groundskeeper. He was also the accountant, chief fundraiser, purchaser, and remunerator. What’s more, he trained the workers, taught genealogy to members, and promoted temple attendance. He even answered the mission president’s request to conduct Hawaiian-language classes for newly arrived missionaries, and he assisted with the community Scouting program.[45]

Over time President Waddoups trained others and delegated many of the responsibilities he had assumed. However, he was always mindful to do whatever he thought was needed to ensure that patrons had a sacred experience in the temple. His hands-on approach acquainted him with the myriad needs involved in maintaining a house of the Lord in proper order and surely set the stage for success during his sixteen-year presidency.

Apostolic Visit of David O. McKay

In 1921, while attending a flag-raising ceremony at the primary school just down the hill from the temple, Elder David O. McKay “envisioned a temple of learning to complement the House of the Lord.” Over three decades later this vision became the Church College of Hawaii (later renamed BYU–Hawaii). Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In 1921, while attending a flag-raising ceremony at the primary school just down the hill from the temple, Elder David O. McKay “envisioned a temple of learning to complement the House of the Lord.” Over three decades later this vision became the Church College of Hawaii (later renamed BYU–Hawaii). Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Although many Church leaders would visit Hawaiʻi and the temple over the years, an apostolic visit in February 1921 would come to have a particularly positive effect on the patronage and reach of the Hawaii Temple for generations. The First Presidency had charged Apostle David O. McKay to visit the Church’s missions and congregations outside North America in order to learn “their spiritual and, as far as possible, temporal needs, and to ascertain the effect of ‘Mormonism’ upon their lives.”[46] Selected to accompany Elder McKay was Hugh J. Cannon, a stake president in Salt Lake City who was a son of George Q. Cannon and an editor of Church publications.

After visiting Japan and China, the men arrived in Hawaiʻi.[47] As guests of President Waddoups in Lāʻie, they visited the temple, where Elder McKay admired the friezes for which he had been a J. Leo Fairbanks’s consultant and where Cannon beheld the temple that his father had foreseen and whose dedication his mother, Jenne (Hugh’s middle name), had attended in person just over a year earlier. However, it was while they attended a flag-raising ceremony at the Church-run school just down the slope from the temple that an important precursor event occurred. President David O. McKay later explained what he saw and felt:

I witnessed a flag raising ceremony by students of the Church school here in Hawaii in Laie. In that little group of students were Hawaiians, what do you call them—Haoles, Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, and Filipinos. . . . That ceremony brought tears to my eyes. Truly the melting pot. . . . [We then met in the nearby chapel] as members of The Church of Jesus Christ—Hawaiians, Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, all the races represented on this island. There we met as one, members of the Church, the Restored Church of Christ. What an example in this little place of the purposes of our Father in Heaven to unite all peoples by the gospel of Jesus Christ.

[From that experience,] we visualized the possibilities of making this . . . the center of the education of the people of these islands.[48]

Elder David O. McKay in 1921 poses with schoolchildren in Lāʻie. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Elder David O. McKay in 1921 poses with schoolchildren in Lāʻie. Courtesy of Church History Library.

A plaque commemorating this event reads: “Elder McKay envisioned a temple of learning to complement the House of the Lord in making Laie the spiritual and educational center of the Church in Hawaii. This vision remained his inspiration and that of his associates until they brought about its literal fulfillment . . . the Church College of Hawaii.”[49] Established in 1955, and later renamed Brigham Young University–Hawaii, this school would form a symbiotic relationship with the temple that continues to further the kingdom of God throughout the Pacific and Asia.

Polynesian Genealogical Association

It has been said that temple and genealogy work is “one work divided into two parts.”[50] That connection was strengthened at the April 1921 Hawaii mission conference with the official organization of the Polynesian Genealogical Association. The Deseret News reported, “This organization promises to be one of the greatest things of its kind in the Church. It is expected that it will do more in the tracing of Polynesian genealogy, than any other system of research; it is a very significant development of temple work.”[51] This genealogical society became an integral part of mission conferences, and “genealogy missionaries” were called and set apart to promote the work throughout the Hawaiian Islands. The society published a book in Hawaiian, He Mau Haʻawina Moʻokūʻauhau (Genealogical lessons), that was uniquely suited to the conditions found in Hawaiʻi.[52]

Many visitors found their way to the temple grounds, where missionaries conducted tours, answered questions, explained the gospel, and dispensed literature. Photo of sailors courtesy of Mark James. Photo of visitors courtesy of Church History Library.

Many visitors found their way to the temple grounds, where missionaries conducted tours, answered questions, explained the gospel, and dispensed literature. Photo of sailors courtesy of Mark James. Photo of visitors courtesy of Church History Library.

Organization of this genealogical society was much more than ancillary. When the Hawaii Temple opened (and for decades thereafter), parameters around gathering names for temple work were quite specific, and shortages of names for which to do temple work was not uncommon. Policy from that era reads:

In the performance of work for the dead, the right of heirship (blood relationship) should be sacredly regarded. When practicable, relatives should represent the dead. . . .

It is advised that individuals having Temple ordinances performed should limit that work to persons bearing the SURNAMES of their parents and grandparents . . . ; that provides four family lines. To include other lines than those involves the probability of repeating Temple ordinances that individuals representing other families may have a better right to have performed.[53]

This careful policy of keeping genealogy work to “four family lines” was helpful in avoiding duplicate temple work and emphasized members’ responsibility for their direct ancestors. Yet occasionally this focused approach left the Hawaii Temple without names needing work. By working with Church leaders, conducting genealogy classes, and assisting individual families and members in gathering their ancestral names, this genealogical society was able to play an invaluable role in the work of the temple.

Temple Bureau of Information (Visitors’ Center)

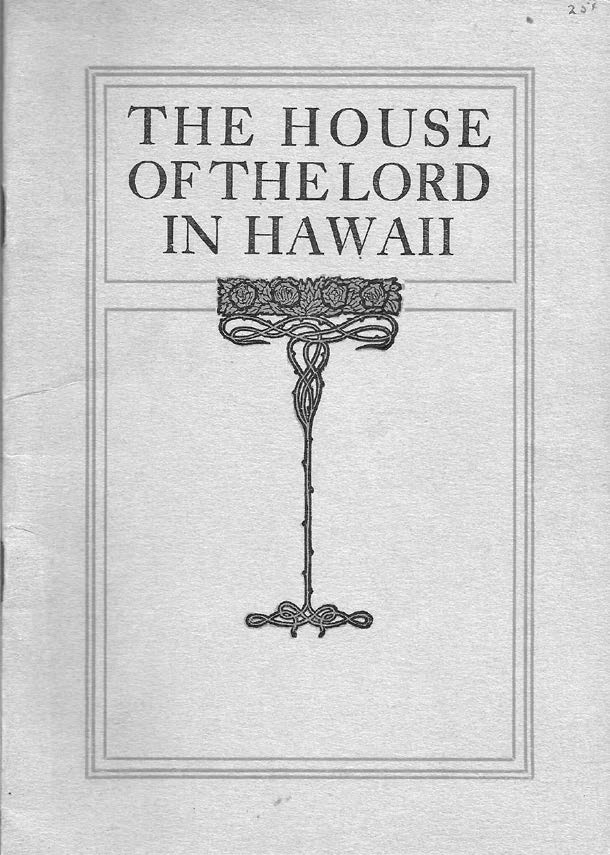

This forty-page booklet offered to visitors describes the purpose of temples while taking the reader on an explanatory tour of the grounds, exterior, and interior of the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

This forty-page booklet offered to visitors describes the purpose of temples while taking the reader on an explanatory tour of the grounds, exterior, and interior of the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Although there were high hopes, likely no one fully anticipated the level of early and sustained success the temple Visitors’ Bureau would achieve. Visiting Hawaiʻi in 1925, John and Mary Hendrickson, Church members from Utah, described their participation in the popular around-the-island sightseeing tour of Oʻahu. Among a group of sixty tourists in ten Cadillac and Packard cars, the Hendricksons described being taken from Honolulu up through the Nuʻuanu Valley and down the Pali (cliff) road. They continued northwesterly with the ocean on their right and rolling hills covered with sugarcane, rice, pineapple, and bananas, all buttressed by sheer green mountains, on their left. In the lead car with the Hendricksons were the secretary of the Honolulu Chamber of Commerce and John Awena-ika-lani-keahi-o-ka-lua-o-Pele Carey Lane, the former mayor of Honolulu.[54] Within a mile or two of Lāʻie, without knowing there were Latter-day Saints on board, the secretary remarked:

The next surprise I have for you is the “Mormon” Temple, situated at the little town of Laie, about a mile distant. . . . The grounds surrounding the temple are magnificent, and the “Mormon” Church owns a plantation of . . . well cultivated sugar cane. The “Mormons” have surely done wonders among the Hawaiians. It is said one-third of all the natives on the Islands belong to the “Mormon” Church. I don’t know how true it is, but the “Mormons” state that the recent Queen Liliuokalani was a member. The native people have been taught industry, morality, and love for God. . . . When you reach the Temple you will be surprised at its magnificence and the surroundings.[55]

At the entrance to the temple grounds, a guide offered literature, and the crowd walked around the grounds taking pictures with the temple in the background. The visitors asked the guide such questions as “Why did the ‘Mormons’ build a temple way out here?” and “Have the ‘Mormons’ similar temples elsewhere?” John Hendrickson understood that a temple in Hawaiʻi was a result of the faithful island Saints. But he also noted “another advantage.” He explained:

Hardly a day passes that there is not a boat landing at Honolulu, carrying passengers from the East or West, and later continuing to the American coast, or to points in the Orient. Steamers . . . seldom pass without a rest for one or more days at Honolulu, where automobiles are always on hand to convey passengers to see the sights of the Island. Comparatively few miss the opportunity of such a trip. This can not be made without passing the “Mormon” temple. Thousands of visitors visit this place every week and get more or less information concerning the Latter-day Saints and their views and never leave without literature, which they take with them and read as they continue on their journey.

In this way the temple is an advertising medium to thousands [upon thousands] of people who have heard but little about the “Mormons” or their views. What I saw and heard, convinced me more than ever of the inspiration of the leaders of our Church, when they decided to build a temple on one of the Hawaiian Islands.[56]

From his daily observation of the Visitors’ Bureau’s success, in 1928 President William Waddoups wrote:

Many thousands of travelers from the four corners of the earth visit our temple grounds each year. Courteous, well-in-formed missionaries are always present at the Bureau of Information, at the front gate, to conduct visitors through the grounds, to answer questions, explain the Gospel, dispense free literature, sell Books of Mormon, and be of any other service possible. Our temple grounds and Bureau of Information are, we believe, one of the important and far-reaching missionary activities of the Church.[57]

Dual Calling

Besides serving as temple president, in June 1926 Waddoups was appointed as mission president, the highest priesthood official in Hawaiʻi, and would serve in this dual capacity for four years.[58] As a result, the Waddoups family moved to Honolulu. This meant that President Waddoups (often with Olivia) made the drive of more than one hour to Lāʻie in the mission car for every session, often returning home very late or staying overnight in Lāʻie with his good friends the Ivinses (Antoine Ivins was the plantation manager), who now occupied the temple president’s home. With so many more demands on his time, President Waddoups turned to steadfast members like Clinton Kanahele to serve in the temple. Despite living in Kaneohe (twenty-five miles from Lāʻie) and serving in various Church assignments, Kanahele would steadily serve in the temple for twenty-seven years.[59]

No one in the Church knew more about gathering Polynesian genealogy than President Waddoups, and no one was more aware of the temple’s need for and occasional shortages of names.[60] With such awareness and expertise, as he traveled throughout the islands in his role as mission president, Waddoups consistently reminded members of the temple’s importance and assisted them with genealogy work. Orpha Kaina recalled President Waddoups staying with her grandparents when visiting the remote village of Hana on the island of Maui. As her grandmother Kaʻahanui’s eyesight deteriorated, President Waddoups assisted with her genealogy, completing her group sheets himself.[61]

In its first decade the temple faced various challenges, yet its leadership, workers, and patrons met those challenges in ways that allowed the Lord’s purposes in the temple to be meaningfully fulfilled and the entire effort to be widely viewed as an admirable success.[62]

Notes

[1] See William M. Waddoups, journal, 1 December 1919, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[2] Mary Ann Wong Soong, “Hawaii Temple Dedication,” Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[3] See Devery S. Anderson, ed., The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846–2000: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), 320–21.

[4] Lydia Colburn and Mary Kelii, interview by Clinton Kanahele, 30 July 1970, Clinton Kanahele Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 31–32. Lydia indicates that “at the time the temple was dedicated, the very first people baptized for in the temple were my sister and others.” FamilySearch.org records the vicarious baptism of Carry Kahuinaonalani Bohling, Lydia’s sister, as having taken place in July 1920.

[5] See Waddoups, journal, 3 December 1919.

[6] Dean Clark Ellis and Win Rosa, “‘God Hates a Quitter’: Elder Ford Clark: Diary of Labors in the Hawaiian Mission, 1917–1920 & 1925–1929,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 28, no. 1 (2007): 17.

[7] See Anderson, Development of LDS Temple Worship, 312, 339.

[8] Waddoups, journal, 5 December 1919. See Brief History of the Life of Isaac Homer Smith, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[9] Ellis and Rosa, “‘God Hates a Quitter,’” entry for 5 December 1919, 18.

[10] Wilford W. King, “Hawaiian Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 3 February 1920, 271.

[11] See Waddoups, journal, 2–5 December 1919.

[12] Waddoups, journal, 11 December 1919.

[13] See Waddoups, journal, 9 January 1920.

[14] “At this time three night sessions a week were being held in the Laie Temple, making it possible for one to work for seven names a week instead of four as formerly.” Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, BYU–Hawaii Archives (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 1 January 1922.

[15] See Eldon P. Morrell, interview, 1981, Kenneth Baldridge Oral Histories, OH-153, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 29.

[16] The number of full-time missionaries assigned to the temple would vary, but in 1921 there were two sisters and five elders laboring in the temple, and the missionaries assigned to the Church school (five sisters and one elder at the time) often assisted with the evening temple sessions as well. See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 20 September 1921.

[17] Ernest Paul Kaulana Elia, interview, 27 December 1979, Kenneth Baldridge Oral Histories, OH-97, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 6.

[18] See Morrell, interview, 21.

[19] See Waddoups, journal, 22–23 December 1919.

[20] See Bella Linkee, interview, Kenneth Baldridge Oral Histories, OH-397, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 2, wherein it is stated that Joseph F. Smith accompanied Hosea Nahinu Kekauoha, “translating all the rituals in Hawaiian to him and that’s how he went through the temple in Salt Lake.”

[21] Waddoups, journal, 6 January 1920.

[22] Susa Young Gates, “Sandwich Island Genealogy,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, October 1919, 145–52. Gates is referring to Thomas Thrum, ed., The Fornander Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folklore (Honolulu, HI: Bishop Museum, 1916–19). The third volume includes Fornander’s collected genealogies and was used to prepare the work for Hawaiʻi’s kingly ancestry shortly after the temple’s dedication.

[23] For more information, see Robert C. Schmitt and Eleanor C. Nordyke, “Influenza Deaths in Hawaiʻi, 1918–1920,” Hawaiian Journal of History 33 (1999), https://

[24] See Waddoups, journal, 19–31 March 1920.

[25] William M. Waddoups, “Personal History of William Mark Waddoups,” William M. Waddoups Papers, 1883–1969, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), 9.

[26] See Waddoups, journal, 1 April 1920. See also King, “Hawaiian Mission,” 411.

[27] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 1 October 1921, reports that “the settlement at Laie had a severe epidemic of Typhoid and Influenza. The Temple and the school closed.”

[28] See Waddoups, journal, 10 June 1921, 168. George Bowles was set apart as a “counselor in the Presidency of the Hawaiian Temple” for the last two years of his mission by Rudger Clawson.

[29] For example, in 1920 Anthon H. Lund was president of the Salt Lake Temple, and “president of the women workers” (later labeled “matron”) was Edna Lambson Smith.

[30] The journals of Olivia and William Waddoups do not mention the word matron or Olivia’s being “set apart.” She did receive a special blessing along with her husband from President Lund, and she later received a blessing at the hand of Elder Clawson in 1921, but neither blessing indicates a specific temple calling.

[31] Waddoups, journal, 4–5 May 1920.

[32] George and Christina Bowles were almost certainly called because of George’s previous experience as mission president in New Zealand. It was known well before the Hawaii Temple dedication that the New Zealand Saints were planning to attend the temple in Hawaiʻi, and the Bowleses were there to help accommodate.

[33] Anderson, Development of LDS Temple Worship, 160, 175, 212, quoting Joseph F. Smith to ward bishops, circa 1912. These donations were often given as one entered the temple.

[34] Waddoups, journal, 24 January 1920.

[35] For example, History of the Hawaiian Mission, 3 April 1921 reads: “The following report was published in the Deseret News of April 30, 1921: At the invitation of the Laie Relief society, all the other Relief society organizations joined in giving a fair, which continued throughout the conference. Most of the articles for sale were Hawaiian handwork, quilts, Lauhala mats, fancy work, leis, etc. The fair was a huge success. Fifty per cent of the proceeds went to the temple and the remaining 50 per cent to the purchasing of an organ for the Laie chapel.”

[36] Waddoups, journal, 29 January 1920. See also King, “Hawaiian Mission,” 411.

[37] See Waddoups, journal, 14 June 1920. History of the Hawaiian Mission, 25 June 1921, quoting from the Deseret News, 25 June 1921, reported, “There is also included in the Laie colony a ‘community house’ which will house about 12 families and is used as a stopping place for LDS members doing temple work at Laie.”

[38] Upon his return from the temple dedication, Rudger Clawson described the previous mission home (Lanihuli), this way: “a two-story frame building with 11 living rooms, kitchen, pantry and bath room. . . . At conference times, as many as 75 people have been comfortably housed and entertained at the mission house.” See Rudger Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 6 January 1920, 231.

[39] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 25 June 1921.

[40] See Morrell, interview, 38–39.

[41] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 31 August 1920.

[42] McAllister’s contribution to the Hawaii Temple did not end with his release. Upon returning to Utah, he resumed work as a recorder in the Salt Lake Temple under its newly appointed president, Apostle George F. Richards. President Richards noted, “Am working with Bro[ther] D[uncan] M McAllister on records trying to get uniformity of ordinances.” Later, with First Presidency approval, McAllister’s work with President Richards was employed in all temples, including the Hawaii Temple. See Anderson, Development of LDS Temple Worship, 182–90.

[43] Robert Plunkett Jr. was born 8 April 1883 in Peʻahi, Maui, Hawaiʻi. His father was from Massachusetts, and his Hawaiian mother was from Peʻahi. He married Julia Keikioewa Ku of Oʻahu on 7 March 1908. See FamilySearch.org.

[44] See “Hawaiian Temple,” Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957, MSSH 284, box 52, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 5.

[45] See Waddoups, journal, January–October 1920.

[46] Hugh J. Cannon, “Around-the-World Travels of David O. McKay and Hugh J. Cannon,” ca. 1925, typescript, 1, microfilm, CHL, quoted in Hugh J. Cannon, To the Peripheries of Mormondom: The Apostolic Around-the-World Journey of David O. McKay, 1920–1921, ed. Reid L. Neilson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2011), 2.

[47] See Hugh J. Cannon, David O. McKay, Around the World, An Apostolic Mission, Prelude to Church Globalization (Provo, UT: Spring Creek, 2005), 58.

[48] Excerpted from President McKay’s groundbreaking services of the Church College of Hawaii (Brigham Young University–Hawaii), 12 February 1955, https://

[49] The plaque is outside the McKay building foyer, mauka (mountain) side, Brigham Young University–Hawaii campus.

[50] Richard G. Scott, “The Joy of Redeeming the Dead,” Ensign, November 2012, 93.

[51] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 3 April 1921. See Deseret News, 30 April 1921.

[52] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 9 April 1922. See Deseret News, 22 April 1922.

[53] Anderson, Development of LDS Temple Worship, 138–39, quoting Joseph F. Smith, ca. 1905, in Instructions Concerning Temple Ordinance Work.

[54] See J. A. Hendrickson, “Why a Temple in Hawaii?,” Improvement Era, January 1926, 258–62. Lane had previously been mayor of Honolulu.

[55] Hendrickson, “Why a Temple in Hawaii?,” 259.

[56] Hendrickson, “Why a Temple in Hawaii?,” 261–62.

[57] William M. Waddoups, “The Hawaii Mission,” Improvement Era, November 1928, 62–64.

[58] See Waddoups, “Personal History,” 6.

[59] See “Hawaiian Temple,” Hui Lau Lima News.

[60] Waddoups, journal, 7–8 October 1929: “We are short of genealogies, and we cannot see where our work is going to come from for the future.” Owing to the shortage of names in Hawaiʻi, the Salt Lake Temple would occasionally send names. See The Salt Lake Temple: A Centennial Book of Remembrance, 1893–1993 (Salt Lake City: Temple Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1993), wherein the entry for 6 January 1925 reads, “The Tuesday baptisms are discontinued in order to send 2,000 names to the Hawaiian Temple.”

[61] See Orpha Kaina, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 10 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU-Hawaii Archives.

[62] See Waddoups, journal, 10 September 1920. From December 1919 through August 1920 the ordinances completed in the Hawaii Temple were as follows: 12,837 baptisms, 1,158 elder ordinations, 2,627 endowments, 671 sealings (husbands and wives), 855 sealings (children), 15 adoptions, for a total of 18,163 ordinances.