Establishing the Church in Hawaiʻi

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Establishing the Church in Hawai'i," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 1–16.

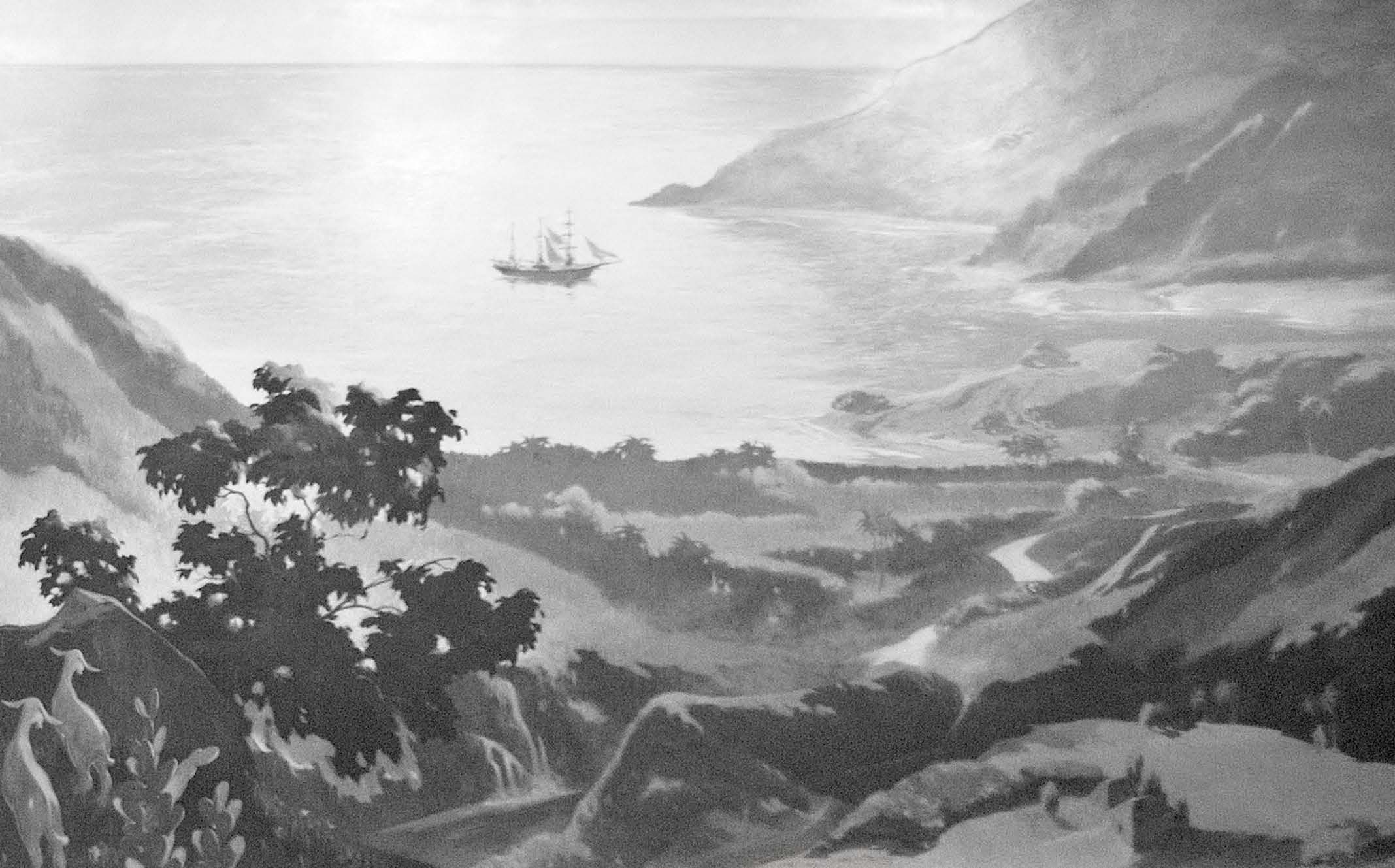

Hawaiian Islands, 1919. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hawaiian Islands, 1919. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Hawaiian Islands make up one of the most isolated archipelagos on the earth. For the skilled ancient seafarers who discovered these remote islands, such a voyage was likely as much a matter of belief as it was skill—if they did not believe it could be done, they would never have attempted it.[1] The consequence of such bold belief and honed skill was the discovery of a beautiful chain of subtropical islands rich in natural resources. What’s more, many Latter-day Saints believe that among those ancient seafarers who reached these islands was a remnant who bore “the promises of the Lord” extended to those “upon the isles of the sea” (2 Nephi 10:21–22).[2] In time their descendants would spread throughout Hawaiʻi’s major islands, founding a civilization that in its remoteness would remain unknown to the rest of the world for hundreds of years.[3]

Discovery by the Outside World

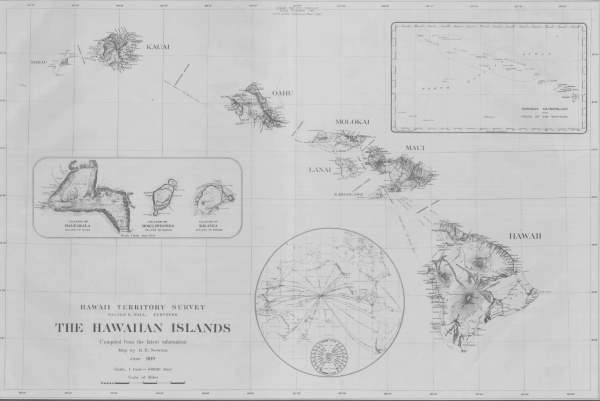

In search of a sea route around North America to the trading regions of Asia, Captain James Cook sailed from England in the summer of 1776 just as the American colonies were declaring their independence. It was while sailing through the Pacific with the intent to reach the North American coast that Cook and his expedition spotted land in mid-January 1778. Though Cook’s ships had encountered uncharted islands before, these were different. According to archaeologist Patrick Kirch, “Cook and his crew had unwittingly stumbled upon one of the last ‘pristine states’[4] to have arisen in the course of world history. In total isolation from the outside world, over the course of centuries the Hawaiians had developed a unique civilization.”[5]

Captain James Cook’s encounter with Hawai‘i put the islands on the map and would bring vast change to the Hawaiian people. Drawing by John Webber, the Cook expedition’s artist. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Captain James Cook’s encounter with Hawai‘i put the islands on the map and would bring vast change to the Hawaiian people. Drawing by John Webber, the Cook expedition’s artist. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Kamehameha Dynasty and Tumultuous Changes

Cook connected the language and physical appearance of these islanders to the vast “nation” of islands far to the south now known by the combined Greek words poly (“many”) and nesia (“islands”)—Polynesia.[6] Cook named the archipelago the “Sandwich Islands,” the name used by the outside world until the 1840s, when the native name Hawaiʻi began to gradually take hold.[7] Though Cook was later killed in a skirmish at Kealakekua Bay in 1779, publication of his contact with Hawaiʻi drastically altered the islands’ future. Now on the map, Hawaiʻi became a stopover for British, French, Russian, American, and other ships, and Native Hawaiians began to trade with, and become increasingly exposed to, the outside world.

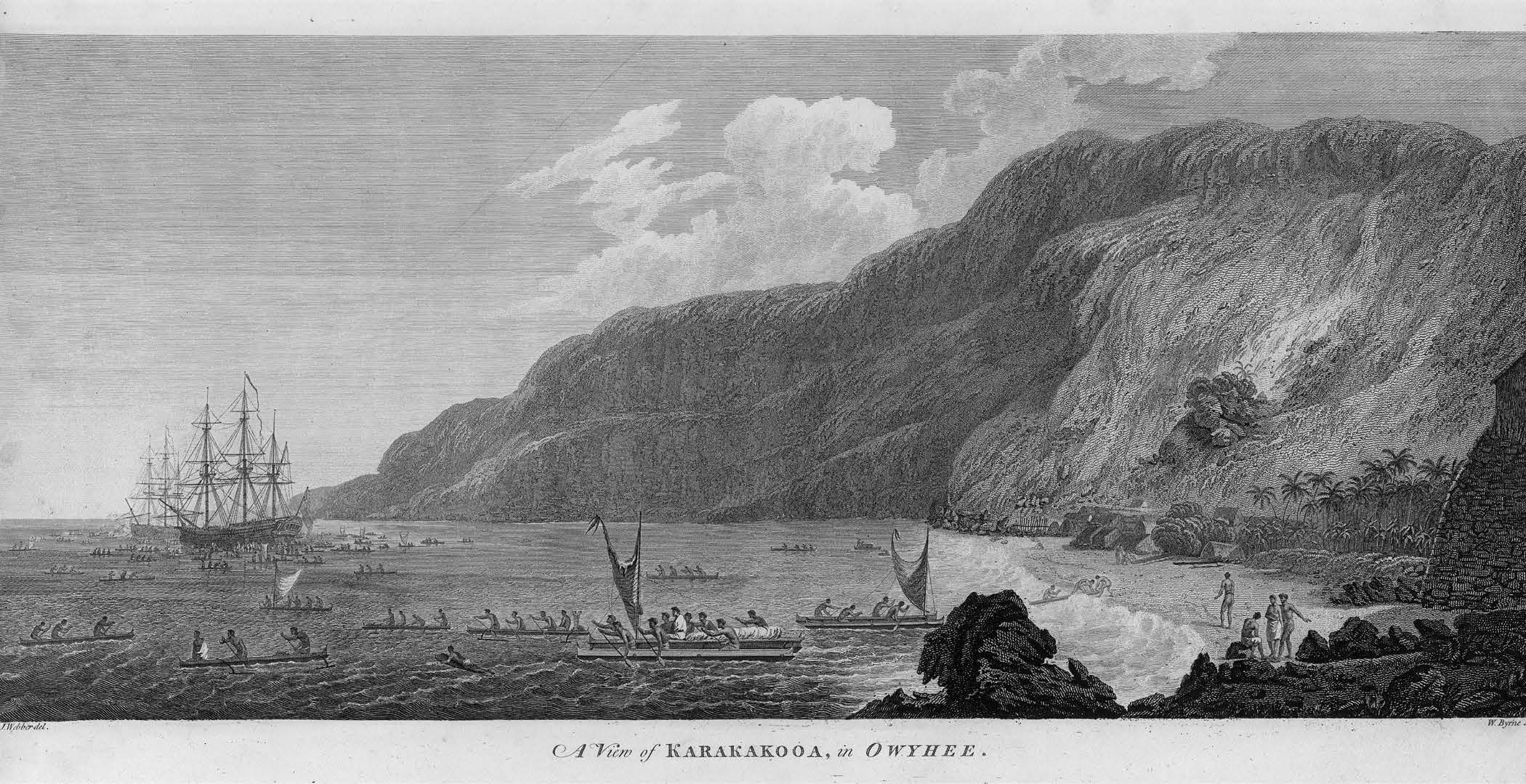

The islands’ exposure to the outside world, however, was not the only instigator of change. Almost coinciding with Cook’s arrival was the rise of the young Hawaiian warrior Kamehameha. Eventually Kamehameha consolidated power, establishing himself as king of the entire Hawaiian archipelago in 1810, and succession of the Kamehameha dynasty lasted through 1893.[8]

Amid mounting outside cultural influences, King Kamehameha had maintained the tenets of Hawaiʻi’s traditional religion during his reign. Yet that quickly changed after his death in 1819 with the succession of his son Liholiho as king. Closely advised by Kamehameha’s widows, Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani, the young Liholiho (Kamehameha II) challenged ancient Hawaiian beliefs by breaking the kapu (taboo), or ritual restrictions that governed many aspects of social behavior. By pronouncing that all the kapu were abolished, and ordering that all heiau (traditional temples) and images be destroyed, Liholiho fundamentally toppled the ancient Hawaiian religion.[9]

King Kamehameha the Great consolidated power across the entire Hawaiian archipelago in 1810, and succession of the Kamehameha dynasty lasted through 1893. The Church arrived and was established in Hawai‘i during this dynasty. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

King Kamehameha the Great consolidated power across the entire Hawaiian archipelago in 1810, and succession of the Kamehameha dynasty lasted through 1893. The Church arrived and was established in Hawai‘i during this dynasty. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This religious void did not last long, however. Within months of Liholiho’s actions, the first Christian missionaries, American Protestants, arrived in Hawaiʻi. They landed in the spring of 1820, the same year Joseph Smith received the First Vision. In addition to teaching the tenets of Christianity, these and subsequent missionaries recorded and established a written form of the Hawaiian language, taught literacy to natives, translated the Bible into Hawaiian, and with support of the Hawaiian ruling class extended Christianity throughout the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.[10]

Trade and Western concepts of economics, land ownership, and politics also produced widespread change. A valued trade commodity, sandalwood was stripped from the islands; then came the rise of whaling, and by the 1840s industrial production of sugarcane had begun. In 1840 King Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) shifted the kingdom’s rule from chiefdom to constitutional monarchy and, on the counsel of his foreign advisers, established a law to privatize land ownership in 1848. Yet of all the changes and challenges Native Hawaiians faced as a result of contact with foreigners, the most devastating was the introduction of infectious diseases for which many natives had little or no immunity. Though estimates vary, by the 1890s, little more than a century after Cook’s arrival, the Native Hawaiian population had fallen from approximately three hundred thousand to near forty thousand.[11]

In the decades following Cook’s arrival, foreign influence increased as the native population declined: civil war had united the islands under the rule of one king; members of the royal family had overthrown the complex kapu system of laws and punishments; and the first Christian missionaries had arrived and, working under the patronage of Hawaiʻi’s ruling family, established a predominantly literate and Christian kingdom. Although the times had been tumultuous, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was able to remain an autonomous nation, one that espoused a degree of religious freedom.[12] This was the setting into which missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints brought the restored gospel of Jesus Christ to the Hawaiian Islands.[13]

Arrival of Latter-day Saint Missionaries

The prospect of sending Latter-day Saint missionaries to the Hawaiian Islands arose early in the history of the Church. As a young man, Addison Pratt had been a whaler and spent time in Honolulu in the early 1820s. Years later he with his wife and four daughters joined the Church and moved to Nauvoo in 1841. Pratt became acquainted with many Church leaders at that time, including the Prophet Joseph Smith and the then President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Brigham Young. As a result of Pratt’s expression of interest, he and three other volunteers (Benjamin F. Grouard, Noah Rogers, and Knowlton F. Hanks) were called to serve in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiʻi) in 1843.[14] Unable to find a ship in the Boston area sailing for Hawaiʻi, Pratt and his companions took passage aboard a whaling ship bound for the South Pacific island of Tahiti, reasoning that they could find passage from there north to their destination.[15]

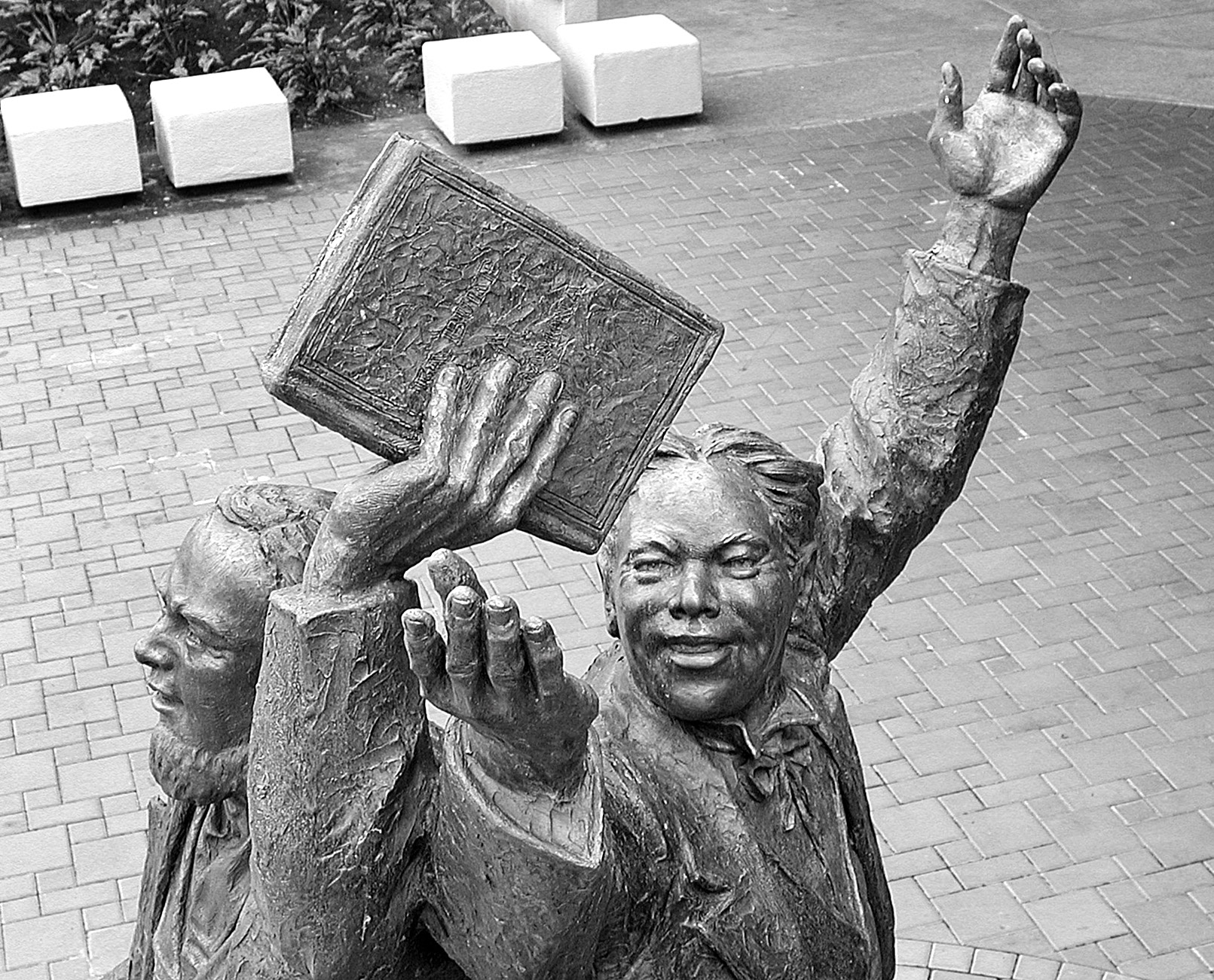

Under the direction of Brigham Young, ten missionaries arrived in Hawai‘i on 12 December 1850. The next day they climbed a nearby mountain, built an altar, and dedicated the Hawaiian Islands for the preaching of the gospel. Mural located in the David O. McKay Building foyer, BYU–Hawaii campus. Photo by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Under the direction of Brigham Young, ten missionaries arrived in Hawai‘i on 12 December 1850. The next day they climbed a nearby mountain, built an altar, and dedicated the Hawaiian Islands for the preaching of the gospel. Mural located in the David O. McKay Building foyer, BYU–Hawaii campus. Photo by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Yet none of these four missionaries would preach in Hawaiʻi. Sadly, Elder Hanks died at sea of a protracted illness, and Elder Rogers returned home not long after arriving in Tahiti. Finding success preaching in the islands around Tahiti, Pratt and Grouard remained there, eventually baptizing thousands. Though the elders did not reach Hawaiʻi and missionary efforts were later halted among the islands where they served, the “gathering” in Polynesia had begun, and this initial success foreshadowed future growth of the Church in the Pacific.[16]

Hawaiian Islands for the preaching of the gospel. Mural located in the David O. McKay Building foyer, BYU–Hawaii campus. Photo by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Hawaiian Islands for the preaching of the gospel. Mural located in the David O. McKay Building foyer, BYU–Hawaii campus. Photo by Monique Saenz courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Much changed in the Church during the years Pratt and his companions served in the Pacific. The year after their departure the Prophet Joseph Smith was martyred, and when Pratt returned in 1848 the main body of the Saints was establishing itself in the Rocky Mountains. It was shortly thereafter that the actual arrival of Latter-day Saint missionaries to Hawaiʻi had an improbable start in the goldfields of California. Gold was discovered in 1848, and though Brigham Young opposed members abandoning life among the Saints to pursue such riches, he made an exception for some responsible men to serve a “gold mission” with the arrangement that any gain would return to Utah.[17] Later, Apostle Charles C. Rich visited this company of elders and, with the authorization of Brigham Young, extended mission calls to several of these men to serve in the Hawaiian Islands.[18] The ten men who accepted the call arrived in Honolulu on 12 December 1850. The next day these elders climbed a nearby mountain and dedicated the islands of Hawaiʻi for the preaching of the gospel.[19] Of this event George Q. Cannon, the youngest of the ten missionaries, recorded:

When we got near to where we wanted to stop we picked up a stone apiece and carried [it] up with us . . . we then made an altar of our stones <and sung a hymn> and then all spoke round what our desires were; & selected Bro. [Hiram] Clark to be mouth [to prayer]. We had the spirit with us I could feel it very sensibly. Our desires principally <were> that the Lord would make a speedy work here on these Islands and that an effectual door might be opened for the preaching of the gospel.[20]

Founding the Church in Hawaiʻi

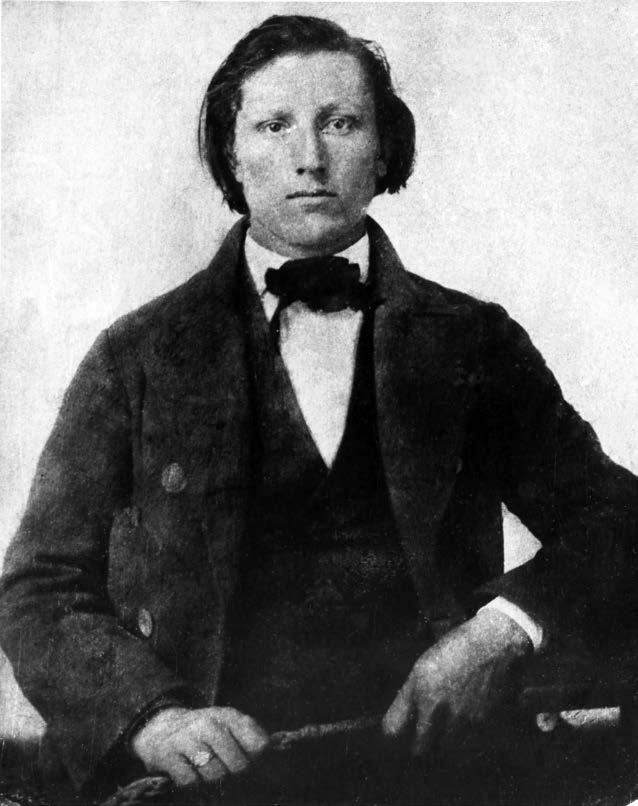

George Q. Cannon was among the first group of missionaries to arrive in Hawai‘i. His determination to learn the Hawaiian language and preach to the native people was a turning point for the mission’s success. Photo circa 1957. © 2004 Utah State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved.

George Q. Cannon was among the first group of missionaries to arrive in Hawai‘i. His determination to learn the Hawaiian language and preach to the native people was a turning point for the mission’s success. Photo circa 1957. © 2004 Utah State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved.

Despite the missionaries’ initial optimism, lack of success and opposition led half of them, when given the choice, to return home that first year. George Q. Cannon later said of his decision to remain, “I felt resolved to stay there, master the language and warn the people of those islands, if I had to do it alone; for I felt that I could not do otherwise.”[21] This was a turning point. Not long thereafter, Cannon met and converted Hawaiian judge Jonathan Hawaiʻi Nāpela, who helped the remaining elders learn the native language and spread the gospel throughout the islands.[22] Within three years, nearly three thousand Native Hawaiians had been baptized.[23]

Significant in these early years, missionaries and Church leaders came to regard Pacific Islanders as descendants of the house of Israel.[24] This biblical connection to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—and particularly Joseph—encouraged missionaries and Church leaders and strengthened Hawaiian members’ understanding of themselves within the restored gospel.[25]

When the Hawaiian Mission commenced, the Church possessed no temples. The Salt Lake Temple had been announced, but groundbreaking was still three years away (1853), and the next operational temple—St. George—was twenty-seven years forthcoming (1877).[26] Thus at that time the idea of building a temple in Hawaiʻi may have seemed unthinkable. Yet the Hawaiian Mission history briefly records that in a meeting held at Waiehu (Maui) on 6 October 1852, “Elder Woodbury spoke in tongues and Bro. Hammond interpreted.”[27] Two of those present wrote what was said in their journals. According to Philip Lewis, then the president of the Hawaiian Mission, Woodbury declared: “The Lord was well pleased with us, that this people [Hawaiians] were a remnant of Israel, that all opposition should be overcome, that temples should be built in these lands and that this people should be redeemed.” William Farrer’s journal likewise confirmed “that temples will be built here.”[28] To be clear, recorded statements that a temple would someday be built in Hawaiʻi were uncommon in the decades following the Church’s arrival in the islands. But that such early statements exist speaks to the deep-seated hope, possibility, and even certainty that a temple would one day be built in Hawaiʻi.

George Q. Cannon and Jonathan H. Nāpela translated the Book of Mormon into Hawaiian (Ka Buke a Moramona). Nāpela (at right) was one of the earliest Hawaiian converts and a noted example of the prominent role Native Hawaiian Saints played in establishing the Church in their own land. Sculpture by Viliami Toluta‘u. Photo by Wallace M. Barrus courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

George Q. Cannon and Jonathan H. Nāpela translated the Book of Mormon into Hawaiian (Ka Buke a Moramona). Nāpela (at right) was one of the earliest Hawaiian converts and a noted example of the prominent role Native Hawaiian Saints played in establishing the Church in their own land. Sculpture by Viliami Toluta‘u. Photo by Wallace M. Barrus courtesy of BYU–Hawaii.

Further, the doctrine of temples and the promise of a temple in Hawaiʻi would likely have offered a degree of comfort to many Hawaiian members. Devastated by the deaths of so many Native Hawaiian members from disease, and wondering why the Lord would permit such loss, Elder Benjamin F. Johnson, a missionary in Hawaiʻi from 1852 to 1855, wrote, “I pondered the subject prayerfully until the light of the Lord shone upon my understanding, and I saw multitudes of their race in the spirit world who had lived before them, and there was not one there with the priesthood to teach them the gospel. The voice of the Spirit said to me, ‘Sorrow not, for they are now doing that greater work for which they were ordained, and it is all of the Lord.’”[29] One can imagine the additional comfort Elder Johnson would have felt knowing that the grandchildren of that generation would build a temple in Hawaiʻi to consummate the efforts of those who left to work beyond the veil.

Joseph F. Smith (sixth Church President) was fifteen years old when called to serve a mission in

Joseph F. Smith (sixth Church President) was fifteen years old when called to serve a mission in

Hawai‘i (1854–57). This mission experience set him on a path of lifelong Church service and

commenced a deep relationship with the Hawaiian people that would last throughout his life. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Amid successes and setbacks, waves of Utah missionaries were sent to Hawaiʻi. Among them was fifteen-year-old Joseph F. Smith (son of Hyrum Smith and nephew of the Prophet Joseph Smith), who served from 1854 to 1857. Joseph F. Smith’s life and leadership would become interwoven with Hawaiʻi and its people through multiple missions and would culminate some six decades later with the construction of the Hawaii Temple during his time as the prophet of the Church.

Notes

[1] See Matthew Kester, “Remembering Iosepa: History, Place, and Religion in the American West” (PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2008), 3.

[2] Those promises may include gathering those who have been scattered, restoring the covenant, and restoring knowledge of “their Redeemer, who is Jesus Christ” (3 Nephi 5:23–26; also 1 Nephi 22:8; 2 Nephi 10:2). On the matter of a remnant of the house of Israel settling in the Pacific Islands, see notes 24 and 25 herein.

[3] Patrick Vinton Kirch, A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawaiʻi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), xi.

[4] By “pristine states,” Kirch means political entities that “arose independently, rather than through interaction with other already existing states” (Island Civilization of Ancient Hawaiʻi, 6).

[5] Kirch, Island Civilization of Ancient Hawaiʻi, 4.

[6] See The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery, ed. J. C. Beaglehole (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for Hakluyt Society, 1955), 263–64. See also Kirch, Island Civilization of Ancient Hawaiʻi, 12.

[7] See Russell Clement, “From Cook to the 1840 Constitution: The Name Change from Sandwich to Hawaiian Islands,” Hawaiian Journal of History 14 (1980): 50–57, https://

[8] See Richard Tregaskis, The Warrior King: Hawaiʻi’s Kamehameha the Great (New York: Macmillan, 1973).

[9] See Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom: Volume 1: Foundation and Transformation 1778–1854 (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1938); Gavin Daws, Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1974); and Julia Flynn Siler, Lost Kingdom: Hawaiʻi’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Venture (New York City: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013).

[10] See Kuykendall, Hawaiian Kingdom, 65–70.

[11] Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Native Hawaiian Population Enumerations in Hawaiʻi, May 2017, https://

[12] Under threat of force from the French government for his suppression of the Catholic Church, King Kamehameha III issued the Edict of Toleration in 1839, which allowed for the establishment of the Catholic Church in Hawaiʻi. In 1840 the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi’s new constitution contained a provision protecting religious freedom. While certainly a favorable development for arriving Latter-day Saint missionaries a decade later, in reality the edict was unable to eliminate all unfair opposition to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[13] For more detail, see R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018), 12–22.

[14] See Eugene M. Cannon, “Tahiti and the Society Island Mission,” Juvenile Instructor, June 1897. Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 2:233, notes the following: “May 23, 1843: We set apart Elders Noah Rogers, Addison Pratt, Benjamin F. Grouard & Knowlton Hanks to take a mission to the Sandwich Islands.”

[15] The six-month voyage took them east across the Atlantic, around the southern tip of Africa, through the Indian Ocean, and on to the Pacific.

[16] For more detail regarding this mission to the South Pacific, see The Journals of Addison Pratt, ed. S. George Ellsworth (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990). See also S. George Ellsworth and Kathleen C. Perrin, Seasons of Faith and Courage: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in French Polynesia (Sandy, UT: Yves R. Perrin, 1994); Fred E. Woods, “Launching Mormonism in the South Pacific: The Voyage of the Timoleon,” in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 191–216; and Brandon S. Plewe, ed., Mapping Mormonism (Provo, UT: BYU Press), 60, which notes, “The mission . . . was grueling and short-lived, but its success foreshadowed the later dynamic growth of the Church in the South Pacific.”

[17] For an overview of the Mormon mining mission, see Eugene Campbell, “The Mormon Gold Mining Mission of 1849,” BYU Studies 1:2 and 2:1 (Autumn 1959–Winter 1960): 19‒31. See also Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1958), 72–76.

[18] Henry Bigler, journals, 25 September 1850, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[19] Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 13 December 1850. Also found in Honolulu Hawaii Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, CHL.

[20] George Q. Cannon, The Journals of George Q. Cannon: Hawaiian Mission, 1850–1854, ed. Adrian W. Cannon, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Chad M. Orton (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 27–28; hereafter cited as Journals of George Q. Cannon.

[21] George Q. Cannon, My First Mission (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1882), 22.

[22] For more on Nāpela, see Fred E. Woods, “A Most Influential Mormon Islander: Jonathan Hawaiʻi Nāpela,” Hawaiian Journal of History 42 (2008): 135–57.

[23] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 6 October 1853. Statistics from the October 1853 Sandwich Islands Mission conference indicate there were “53 branches with a total membership of 2986 members.”

[24] Various early missionaries to Hawaiʻi made this connection. In 1852 William Farrer recorded: “The Lord is well pleased with the labors of his servants on the islands, that the angels of the Lord were near us then, that the people we were laboring among were a remnant of the seed of Joseph, that they would be built up on these islands, and that temples will be built here, etc.” (William Farrer diary, 6 October 1852, CHL). See Philip B. Lewis’s comments noted in Journals of George Q. Cannon, 207n37, entry for 6 October 1852. Samuel E. Woolley noted that while serving on Maui (1850–54), George Q. Cannon learned the Native Hawaiians “were of the seed of Abraham . . . because the lord told him so at Lahaina” (Samuel E. Woolley diary, 28 December 1900, CHL). Moreover, Brigham Young confirmed the connection of Hawaiians to the house of Israel in a letter he sent to King Kamehameha V in 1865 (see “Letter of Mr. Young . . . to his majesty, L. Kamehameha the Fifth, King of the Hawaiian Islands,” M270.3 L650 1865, CHL).

[25] There are several possibilities of how, when, and to what extent a remnant of the house of Israel found its way to the Pacific Islands. Supporting the possible presence of the house of Israel there while leaving open the specifics, President Joseph Fielding Smith stated, “The Lord took branches [of Israel] like the Nephites, like the lost tribes, and like others that the Lord led off that we do not know anything about, to other parts of the earth. He planted them all over his vineyard, which is the world” (Joseph Fielding Smith, Answers to Gospel Questions [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957], 4:203–4). Elder James E. Talmage wrote, “The Israelites have been so completely dispersed among the nations as to give to this scattered people a place of importance as a factor in the rise and development of almost every large division of the human family. This work of dispersion was brought about by many stages, and extended through millenniums” (James E. Talmage, The Articles of Faith [Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1899], 328). There are also more specific assertions of a Polynesian connection with the house of Israel outlined in Russell T. Clement, “Polynesian Origins: More Word on the Mormon Perspective,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13, no. 4 (Winter 1980): 88–89. See also Robert E. Parsons, “Hagoth and the Polynesians,” The Book of Mormon: Alma, the Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 249–62.

[26] The Salt Lake Temple was announced 28 July 1847, with the groundbreaking on 14 February 1853 and the dedication on 6 April 1893. The St. George Temple was announced and ground was broken on 9 November 1871, with the dedication on 6 April 1877.

[27] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 5 October 1852.

[28] See comments by Philip Lewis and reference to William Farrer in Journals of George Q. Cannon, 207n37, entry for 6 October 1852.

[29] Benjamin F. Johnson, My Life’s Review (Independence, MO: Zion’s Printing and Publishing, 1947), 157.