The Dedication: “A Spiritual Feast Never to Be Forgotten”

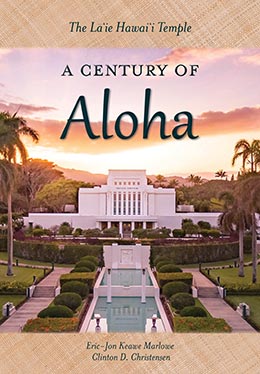

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "The Dedication: 'A Spiritual Feast Never to Be Forgotten,'" in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 57–70.

President Heber J. Grant and his party disembark in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, on 21 November 1919 before the Hawaii Temple dedication. From left: Arthur Winter, Sarah J. Cannon, Rudger Clawson, Anthony H. Lund, President Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Nibley, and Stephen L Richards. Courtesy of Church History Library.

President Heber J. Grant and his party disembark in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, on 21 November 1919 before the Hawaii Temple dedication. From left: Arthur Winter, Sarah J. Cannon, Rudger Clawson, Anthony H. Lund, President Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Nibley, and Stephen L Richards. Courtesy of Church History Library.

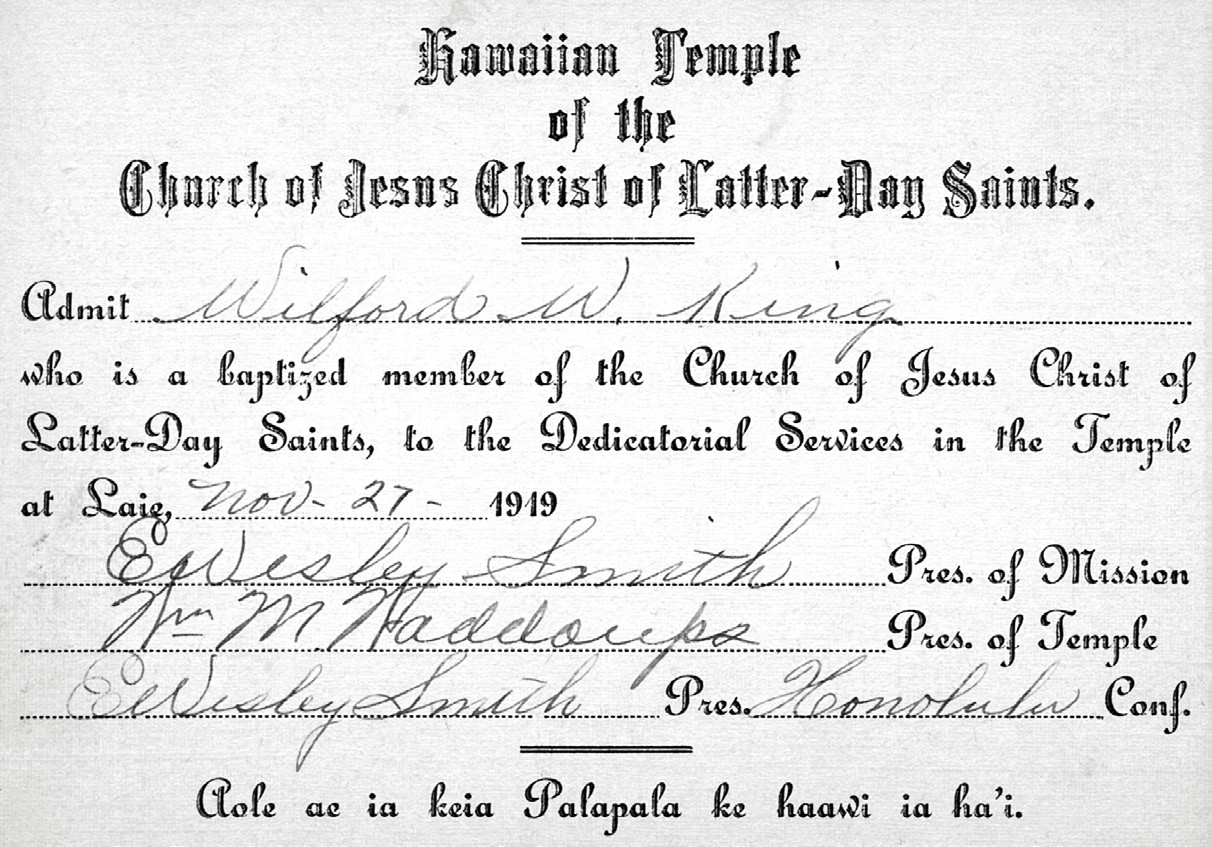

On 13 November 1919 a cable arrived from President Heber J. Grant with the brief but welcome words “Dedication thirtieth. Inform Wesley.” In the sixteen months since the completion of the temple, this was the first definitive date given for its dedication, and those laboring at mission headquarters straightway sent out permit cards to local leadership to give to members who desired to attend the long-anticipated event.[1]

President Grant Arrives

On Friday, 21 November 1919, a large gathering of Saints greeted President Grant and his party as they disembarked in Honolulu. President Grant was accompanied by Anthon H. Lund, First Counselor in the First Presidency; Rudger Clawson, Acting President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles; Stephen L Richards, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve; Charles W. Nibley, Presiding Bishop; and Arthur Winter, Church Board of Education secretary, who would transcribe the dedication proceedings.[2]

That evening the visitors were treated to an elaborate lūʻau and were entertained by the Saints in Honolulu.[3] Saturday was President Grant’s birthday, and that morning he and his party made the scenic drive to Lāʻie, where all but Bishop Nibley (who had accompanied Joseph F. Smith in 1917) caught their first view of the temple. As the group left their automobiles, the children awaiting their arrival began singing “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet,” and then all voices joined in. A great feast had been prepared, including a birthday cake and a flower-laden numeral 63 signifying President Grant’s age. The reception warmed the prophet’s heart considerably.[4]

After lunch the Brethren toured the temple and grounds. All agreed that the grounds and setting “were the most beautiful of any of our Temples.”[5] Yet several critiques were made of particular items within the temple, including the small size of the baptismal font, the quality of some paintings, and the color scheme of certain furnishings.[6] Far from any disrespect, this was their duty—to ensure that the edifice would be worthy of being dedicated as a house of the Lord. The evening ended with a large gathering and formal serenade of President Grant and his party on the lawn of the Lanihuli mission home, where they were staying.

Members Gather to Lāʻie

At some point between President Grant’s short cable message on 13 November and the early days of his arrival in Hawaiʻi, the date for the initial dedicatory service was moved up from the thirtieth to the twenty-seventh of November, Thanksgiving Day. Word of this change having spread, on Tuesday large companies of Saints began arriving in Honolulu on steamers from other islands.[7]

Receiving word that President Heber J. Grant would arrive later that month, members wishing to attend the temple dedication in late November were promptly issued permit cards (recommends). Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Receiving word that President Heber J. Grant would arrive later that month, members wishing to attend the temple dedication in late November were promptly issued permit cards (recommends). Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Of traveling with her family as a young child from Hilo to Lāʻie for the temple dedication, Abigail K. Kailimai recalls: “We were all dressed up to go and mom made a new white dress. Of course, we children were happy because we were going to be riding the boat.” And of the train ride from Honolulu around Kaʻena Point and on to Lāʻie, she remembered “Chinese men coming on the train with their baskets of fruit. They were saying pineki, alani—they were selling peanuts and oranges. We came all the way with the other families and we were having fun.”[8]

Most Hawaiian members were of modest means, and the cost of travel and lodging for those from the outer islands was formidable. Living on Kauaʻi, Sisters Sarah Wong-Kelekoma Sheldon and Mary Ann “Mele” Wong Soong recalled that although their family was short the necessary funds, after fasting and prayer they determined to “go with their own food, and [they found that] the homes [of] friends [and] of members of the church were open for those traveling for the dedication.”[9] Some members on Oʻahu who could not afford the train traveled by horse and buggy to Lāʻie, and others even walked the distance.[10]

On Wednesday, the day before the dedication, a group of about three hundred Saints arrived by train. “They presented an animated scene at the depot as they stepped off the cars in their light-colored summer clothes and with smiling countenances,” wrote President Clawson, and “friends from the colony [Lāʻie] were there to greet them with words of welcome and brotherly love, and to provide comfortable quarters for them.” This scene repeated itself on Thursday when another trainload of Saints arrived just hours before the first dedicatory session. In all, President Clawson estimated that during the dedicatory services, ending Sunday the thirtieth, “about 1,200 to 1,500 Saints gathered at [Lāʻie].”[11]

The Saints in Lāʻie welcomed and accommodated hundreds of members arriving by train for the temple dedication. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The Saints in Lāʻie welcomed and accommodated hundreds of members arriving by train for the temple dedication. Courtesy of Church History Library.

To accommodate this number of Saints, five dedicatory sessions were conducted. One was Thursday, two were on Friday, and two were on Sunday, with the Sunday morning session being designated for children. During these dedication services, mission conference meetings (the first in two years) were also held. As Elder Wilford King reported, “While the dedicatorial services were being held, sessions of the conference [met], so that those who could not attend the services in the temple could be spiritually fed.”[12] Of the grand event the Deseret Evening News reported, “It was a wonderful time of rejoicing during the four days of temple services and conference meetings.”[13]

Preparing the Dedicatory Prayer

In Lāʻie, President Grant dictated the dedicatory prayer the evening before, and the morning of, the first dedicatory session of the temple. Of the prayer he stated, “I am constrained to acknowledge the inspiration of the Lord to me in its preparation.” Courtesy of Church History Library.

In Lāʻie, President Grant dictated the dedicatory prayer the evening before, and the morning of, the first dedicatory session of the temple. Of the prayer he stated, “I am constrained to acknowledge the inspiration of the Lord to me in its preparation.” Courtesy of Church History Library.

President Grant considered delivering the dedicatory prayer without previous preparation, intending instead to pray “as the Spirit might suggest in the temple.”[14] However, on the day before the first dedicatory session, President Grant dictated some notes to Arthur Winter of what he wanted to include in the prayer.[15] Later, concerned that his notes “might be a little confusing and perhaps would cause some delay in the delivery,”[16] that evening President Grant counseled with his brethren, and it was thought best to dictate the prayer “for fear of omitting some item of importance.”[17] That night he dictated part of the prayer to Winter and the rest the next morning. “I did not hesitate a moment while dictating it,”[18] explained President Grant, “and after reading it I feel it is so far superior to any ordinary prayers that I have delivered that I am constrained to acknowledge the inspiration of the Lord to me in its preparation.”[19]

First Dedicatory Session

At last all was ready for what President Rudger Clawson called “the greatest day in all the history of Hawaii.”[20] Invitations to attend the first dedicatory session went to branch presidents; to Sunday School, Relief Society, Mutual Improvement Association, and Primary officers (almost all Native Hawaiians); and to the full-time missionaries.[21] Then, around two o’clock p.m. on 27 November 1919 (Thanksgiving Day), this group of 310 people dressed in white were admitted into the temple upon presenting their recommends. They passed through the various rooms and were ultimately seated in the celestial and terrestrial rooms.[22] President Grant presided over and conducted the first session.[23]

To open the dedication, a twelve-member choir sang a special hymn, “A Temple in Hawaii.”[24] Following the hymn, President Grant expressed his sorrow that President Joseph F. Smith was not there to dedicate the temple, adding that he felt it a personal honor and great pleasure to do so. Then, requesting that all present unite their faith and prayers with his in asking the Lord to accept this beautiful edifice, President Grant offered the dedicatory prayer.

The dedicatory prayer

On 27 November 1919 (Thanksgiving Day), a group of 310 people dressed in white were admitted into the temple for the first dedicatory session. Four more dedicatory sessions would be held in the days that followed. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

On 27 November 1919 (Thanksgiving Day), a group of 310 people dressed in white were admitted into the temple for the first dedicatory session. Four more dedicatory sessions would be held in the days that followed. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Although offered by the prophet, the dedicatory prayer for the Laie Hawaii Temple is communal, using we throughout to represent at minimum all present, and begins with deep gratitude for the “privilege” to dedicate a temple to the living God. Thanks is given for the restoration of the gospel with its priesthood power and for the devoted service of previous prophets and apostles of this dispensation. This thankfulness for past Church leaders is punctuated by a petition for blessings upon current Church leadership, ranging from the First Presidency to the leaders of wards and branches throughout the entire Church.

The prayer then gives particular “gratitude and thanksgiving” for George Q. Cannon, Joseph F. Smith, and Jonathan H. Nāpela and their contributions to the coming forth of the gospel in Hawaiʻi. Thanks is also given for the thousands of Hawaiians who in the past accepted the gospel and endured faithfully to the end, and for those who were then living the gospel and “have the privilege of entering into this holy house, and laboring for the salvation of the souls of their ancestors.”

A combination of gratitude, acknowledgment, and requested blessings for various individuals follows. Then, about halfway through the prayer, President Grant petitions the Lord to accept the temple:

We now thank thee, O God, our Eternal Father, for this beautiful temple . . . and we dedicate the grounds and the building, with all its furnishing and fittings, and everything pertaining thereunto, from the foundation to the roof thereof, to thee, our Father and our God. And we humbly pray thee, O God, the Eternal Father, to accept of it and to sanctify it, and to consecrate it through thy Spirit for the holy purposes for which it has been erected.

“We beseech thee,” the prayer continues, “that thy Spirit may ever dwell in this holy house and rest mightily upon all who shall labor as officers and workers in this house, as well as all who shall come here to perform ordinances for the living or for the dead.” Further petition follows that “all who come upon the grounds which surround this temple . . . [may] feel the sweet and peaceful influence of this blessed and hallowed spot.”

The prayer then makes a distinct and prescient request that the Lord “open the way before the members of the Church in . . . all the Pacific Islands, to secure the genealogies of their forefathers, so that they may come into this holy house and become saviors unto their ancestors.”

Reminding the listener that God’s concern extends to the entire human family, thanks is given and blessings are petitioned for various global events, governments, and leaders of that time. Then the prayer weaves the role of a temple into an overarching gratitude for the gospel of Jesus Christ, its redemptive power, and our knowledge of it all through the Prophet of the Restoration, Joseph Smith.

Nearing its end, the prayer turns specifically to the Hawaiian people. Acknowledging their difficult history and the challenges that lie ahead, the prayer pleads for their well-being, asking that they may “increase in numbers and in strength and influence.” It asks as well that the promises unto them as a remnant of the house of Israel may be fulfilled, and that they may further increase in their love for God and Jesus Christ and in their faithfulness in keeping the commandments. Then the prayer speaks of their beloved islands: “We pray thee, O Father, to bless this land that it may be fruitful, that it may yield abundantly, and that all who dwell thereon may be prospered in righteousness.”

In closing, the prayer petitions blessings for Church members throughout the world. It then concludes:

We have dedicated this house unto thee by virtue of the Priesthood of the Living God which we hold, and we most earnestly pray that this sacred building may be a place in which thou shalt delight to pour out thy Holy Spirit in great abundance, and in which thy Son may see fit to manifest himself and to instruct thy servants. In the name of Jesus Christ our Redeemer. Amen and Amen.[25]

The prayer occupied about twenty-five minutes, and President Waddoups called it “a beautiful gem of praise and thanksgiving.”[26] The Relief Society Magazine declared the prayer “a masterpiece of simple diction, wide vision, and touching appeal. Indeed, it is inspired and beautiful in its completeness of detail.”[27]

At the close of the dedicatory prayer, the choir and congregation sang “Praise to the Man,” after which all present united with President Grant in the Hosanna Shout, accompanied by the waving of handkerchiefs. The shout, an expression of worship and of gratitude, was done “with deep feeling and inspirational effect” on that day of thanksgiving.[28]

Speakers in the first session

The Hosanna Shout was followed by talks from all the visiting Brethren, as well as remarks from former mission president Samuel E. Woolley, President E. Wesley Smith, and President William M. Waddoups (the last three delivered a portion of their remarks in Hawaiian). Also, President Grant asked Sarah Jenne Cannon[29] and a number of missionaries to briefly share their thoughts.[30] All said, sixteen people spoke in the first session, and a few of their comments follow.

President Lund warmly congratulated the Hawaiian Saints on having a temple in their midst.[31] Then he strongly encouraged genealogy work, promising that if they would do all in their power to find their departed relatives and friends, then the Lord would make the veil thinner and reveal unto them names that they could not otherwise find by themselves.

President Grant honored long-time mission president Woolley by inviting him to speak directly after President Lund of the First Presidency. Likely no person at the dedication had been more instrumental in the temple’s realization than Woolley. He shared comments that President George Q. Cannon made to him nineteen years earlier about a possible temple in Hawaiʻi and how he (Woolley) had labored from that day to bring about the conditions upon which that could happen.[32] He noted there were setbacks along the way but that through the providence of the Lord and the perseverance of the Hawaiian Saints and the missionaries, the Lord had truly blessed them.

President Waddoups said that if in his service he could be an instrument benefiting his brothers and sisters of the islands, it would be the greatest pleasure of his life, and he pledged, “What I have I give to you.” Then, speaking directly to the islands’ Church leadership, gathered specifically in that first dedicatory session, President Waddoups asked that they carry the spirit of the meeting with them to their various branches so they could teach their fellow members by example and by precept the spirit of the Lord’s house. Then Elder Richards explained that “the temple is something more than a beautiful building. It is a monument to the great truths of the gospel, and stands for all that is best and holiest in life. While it is a house for the salvation of the dead it should never be forgotten that it is also a house for the living and intended to stimulate us to higher things.”[33]

Speaking last, President Grant affirmed that the Lord had accepted their offering of the temple. Then, among other remarks, he read President Joseph F. Smith’s account of a dream he had as a young missionary in Hawaiʻi that had been published only weeks earlier in the Improvement Era. The first part reads:

I dreamed that I was on a journey, and I was impressed that I ought to hurry, hurry with all my might, for fear I might be too late. I rushed on my way as fast as I possibly could, and I was only conscious of having just a little bundle, a handkerchief with a small bundle wrapped in it. . . . Finally I came to a wonderful mansion, if it could be called a mansion. It seemed too large, too great to have been made by hands, but I thought I knew that was my destination. As I passed towards it, as fast as I could, I saw a notice, “Bath.” I turned aside quickly and went into the bath and washed myself clean. I opened up this little bundle that I had, and there was a pair of white, clean garments. . . . And I put them on. Then I rushed to what appeared to be a great opening, or door. I knocked and the door opened, and the man who stood there was the Prophet Joseph Smith. He looked at me a little reprovingly, and the first word he said: “Joseph, you are late.” Yet I took confidence and said: “Yes, but I am clean—I am clean!”[34]

President Grant concluded his remarks with a plea that the people keep themselves free from sin so they might be worthy in all respects to enter the house of the Lord. He bore powerful witness that the restored gospel is “in very deed the plan of life and salvation.” President Clawson observed, “The president’s inspired discourse stirred the people to their very souls.”[35]

In closing, the congregation sang “The Spirit of God,” and the benediction was given by Elder David Keola Kailimai. The first dedicatory session lasted four hours. President Waddoups wrote in his journal, “Never have I been in a place where I felt more of the sweet peaceful influence of the Lord as much as in this dedication meeting.”[36] Missionary Cassandra Debenham Bailey said: “It was by far the most impressive and inspirational meeting I ever remember attending.”[37] And President Clawson reported that “all seemed to feel that the Lord had accepted the beautiful prayer of dedication and the house which had been erected by the Church and the good people of Hawaii was now dedicated to his service.”[38] In the months that followed, President Grant’s dedicatory prayer was widely distributed throughout the Church, printed in its entirety in no fewer than eight Church-related publications.

Additional Dedicatory Sessions

In the days that followed, four other dedicatory services were given: two on Friday and two on Sunday. President Grant’s prayer was read verbatim in each session with the exception of Sunday morning, which was given especially for the children. President Grant and those who accompanied him spoke at all sessions, as did the temple president and current and former mission presidents. Each service also included a number of brief testimonies borne by the traveling missionaries and others. President Clawson recorded, “There were 81 speakers in all at the five services, and a total of 1,239 people were in attendance.”[39]

Friday morning

Just before the Friday morning dedicatory session, “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi, the woman who cared for Joseph F. Smith when he was a young missionary, was carried up to the celestial room (she being blind and unable to walk) and seated in a place of honor toward the front.

During the session President Grant expressly introduced Duncan McAllister, telling those present that they were honored to have such a man be their temple recorder. In his remarks McAllister recalled his time as a young missionary in Liverpool, England, in the early 1860s when President George Q. Cannon presided there and Joseph F. Smith oversaw the Sheffield district therein. McAllister explained that when those two men met it seemed their favorite conversation was Hawaiʻi—their experiences, the islands’ beauty, and the wonderful people. McAllister said that, on hearing these conversations, he often felt he would like to see Hawaiʻi and mingle with its people, then concluded that this call (more than fifty years later) to assist them in their labors in the house of the Lord seemed a crowning blessing of his life.

In his concluding remarks in the Friday morning session, President Grant voiced his hope that the temple would serve the Saints in the broader Pacific and beyond. He also noted that it was the desire of some of the faithful Saints in New Zealand, and other islands of the Pacific, to be present at the temple dedication, and he lamented that he was unable to provide the necessary notice for them to do so. But he gave his assurance that those members would come later. Then, in closing, President Grant specifically honored Ma Manuhiʻi for her care of and devotion to the prophet Joseph F. Smith, noting that he personally had been inspired by her story of devotion.

Friday afternoon

In Friday afternoon’s dedicatory session, President Clawson, in order to share salutations from the Relief Society general board, borrowed a traditional greeting used among congregations of Hawaiian Saints. Drawing a handkerchief from his pocket, he held it aloft by its four gathered corners. As he explained he had brought the love or aloha of President Emmeline B. Wells and the rest of the general board to the sisters of Lāʻie, he opened up the handkerchief and all the Saints responded with a hearty “A-lo-ha!” Then he symbolically folded the handkerchief containing their response and returned it to his pocket to take home with him.[40] This practice appears to have begun among the Hawaiian Saints in 1870, and it became the custom of speakers to begin their remarks with “Aloha,” to which the congregation similarly responds, a tradition still practiced in congregations throughout the Hawaiian Islands.[41]

There were no temple dedicatory sessions on Saturday. Instead the day was given completely to the mission conference.[42]

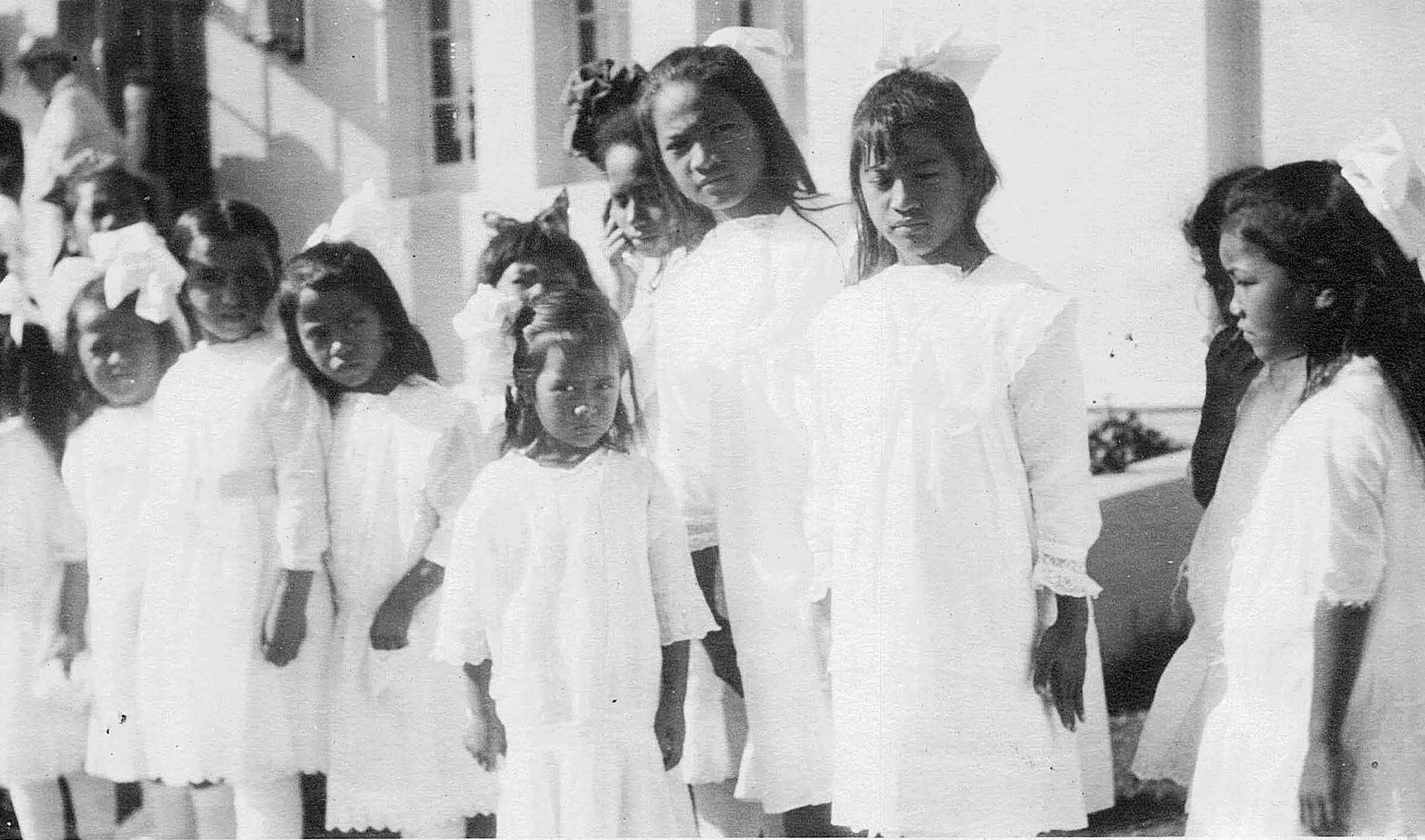

Sunday morning

Line outside the temple for the Sunday morning dedicatory session, which was conducted entirely for the benefit of Primary-age children. Courtesy of Charles Ray Killian family.

Line outside the temple for the Sunday morning dedicatory session, which was conducted entirely for the benefit of Primary-age children. Courtesy of Charles Ray Killian family.

The Sunday morning dedicatory service was given for the benefit of children under twelve years of age, of whom there were 235 present, mostly Hawaiians.[43] This followed the example of the Salt Lake Temple dedication, which included a handful of children’s sessions. The dedicatory prayer was not offered during this session; however, a number of sister missionaries and the usual brethren spoke.[44] President Clawson added, “The children, as they sat there . . . in white, listening attentively to the testimonies and remarks made, presented an inspiring picture.”[45]

Mary Ann Wong Soong was nine years old at the time of the dedication and recalled, “The children . . . were taken into the temple and walked up and up until we came to a room that President Heber J. Grant was in. He welcomed us and talked to us. He asked us to sing one of his favorite songs which was, ‘Who’s on the Lord’s Side, Who?’, which we all did. He sang with us too. This was such an exciting time because it was the first time I had ever seen a prophet of the Lord.”[46] President Waddoups, whose own children attended, concluded, “The children enjoyed it very much. . . . It will I think and hope never be forgotten by them.”[47]

Sunday afternoon

In the final dedicatory session, Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley noted the magnificent spirit of sacrifice involved in laying the foundations of the Hawaii Mission, as well as the Church, and marveled at what had been achieved—evidenced by the new temple—by such sacrifice. Then President Clawson remarked that a great work for the Hawaiian people had been done and was ongoing in the spirit world by their ancestors who had received the gospel and passed away. He added that George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith had undoubtedly joined in that work. He then emphasized that the temple is a bridge over death, connecting the work on both sides of the veil.

Just before the closing prayer of the final session, William M. Waddoups was set apart as temple president by President Grant. Of his being set apart, President Waddoups recorded, “If I may have strength to live that I may obtain the blessings that were pronounced upon my head I will be a proud and happy man. I know that if I do my duty God will magnify me and I will be able.”[48]

Days Never to Be Forgotten

When thinking back on that four-day event, President Grant said, “I am at a loss to give thanks to the Lord for His goodness to me every time I think of the inspiration of His Spirit which came to me in praying and speaking at the dedication of the Hawaiian Temple.”[49] He proclaimed the events “a spiritual feast never to be forgotten.”[50] President Grant was not alone in his feelings. President Clawson described the dedication services as “impressive and inspiring to the last degree.”[51] Bishop Nibley, referring to the “privilege” it was to be present at the services, said, “I am delighted, beyond words to express.”[52] President Waddoups concluded, “These were never to be forgotten days for all who attended the dedication service.”[53]

The Hawaii Temple dedication—four days in the picturesque village of Lāʻie enjoying the generosity and fellowship of the Hawaiian Saints, together with family and loved ones and in the presence and under the tutelage of the Lord’s prophet, with everyone united in the dedication of a temple to God—provided an extraordinary experience for all who were able to attend.

Notes

[1] Wilford W. King, missionary journal, 12 October 1919, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives), 191.

[2] See Rudger J. Clawson, “The Hawaiian Temple,” Millennial Star, 8 January 1920, 27–32. This article consists of “letters from President Rudger Clawson, in the Deseret News, from which we quote.”

[3] See Clawson, “Hawaiian Temple,” 28.

[4] See Clawson, “Hawaiian Temple,” 29.

[5] William M. Waddoups, journal, 22 November 1919, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[6] See Waddoups, journal, 22 November 1919.

[7] See Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI, 25 November 1919.

[8] Quoted in Gail Kaapuni, “The Temple in Our Lives,” 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[9] Quoted in Richard and Jennie Sheldon, “Temple Memories,” Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives. See Mary Ann Wong Soong, sacrament meeting talk on the Hawaii Temple dedication, Kapaa II Ward, late 1990s, notes taken and transcribed by Linda Gonsalves, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[10] See Kanani Casey, “Solomon Kaonohi–Laie Hawaii Temple Dedication–1919,” Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[11] Rudger Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, 11 January 1920, 1. This article is a complete reprint of “Impressive Dedicatory Service and Prayer in New Hawaii Temple: Full Text of Dedicatory Prayer by President Heber J. Grant,” Deseret Evening News, 13 December 1919, section 4, page 9, with excerpts from “Church Officials Return from Trip to Hawaiian Isles: President Grant and Party Pronounce Visit One of Supreme Delight from Beginning to End,” Deseret Evening News, 18 December 1919. The editor of the Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine notes that the article includes “proceedings reported by President Rudger Clawson.”

[12] Wilford W. King, “Hawaiian Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 3 February 1920, 271.

[13] “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 6 January 1920, 229–32. This article is a complete reprint of “Church Officials Return from Trip to Hawaiian Isles,” Deseret Evening News, 18 December 1919.

[14] Heber J. Grant to Charles W. Penrose, 1 December 1919, Heber J. Grant Collection, MS 1233, Historian’s Office letterpress copybooks, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), 55:256.

[15] An entry in President Grant’s journal notes, “During the afternoon I dictated part of the Dedicatory prayer to Bro Arthur Winter.” Heber J. Grant, journal, 26 November 1919, Heber J. Grant Collection.

[16] Grant, journal, 27 November 1919.

[17] Grant to Penrose, 1 December 1919.

[18] Heber J. Grant to George Albert Smith, 30 January 1929, Heber J. Grant Collection, 55:579.

[19] Grant to Penrose, 1 December 1919.

[20] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 10.

[21] See Waddoups, journal, 27 November 1919.

[22] See Waddoups, journal, 27 November 1919.

[23] See Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 2.

[24] The lyrics to this song began as a poem composed by Ruth May Fox (then First Counselor in the Young Women General Presidency) after she heard the announcement that a temple would be built in Hawaiʻi. Her poem was published in the December 1915 Improvement Era, and Orson Clark, then a missionary in Hawaiʻi, composed music to the poem. In March 1916 the song was performed for President Joseph F. Smith while he was in Hawaiʻi observing the progress of the temple’s construction. Moved by the song, President Smith took a copy home with him, and in the April 1915 general conference he personally read the words to the congregation and had it sung by a quartet (see Conference Report, April 1916). The temple dedication choir was composed of twelve singers selected in equal numbers from the Lāʻie and Honolulu choirs. For more detailed information, see Dean Clark Ellis, “A Temple in Hawaii,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society (2010): 31; and Lydia Colburn, interview by Clinton Kanakele, 30 July 1970, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[25] Dedicatory Prayer, Laie Hawaii Temple, 27 November 1919, https://

[26] Waddoups, journal, 27 November 1919.

[27] “Dedication of the Hawaiian Temple,” Relief Society Magazine, February 1920, 81.

[28] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 9.

[29] “Dedication of the Hawaiian Temple,” Relief Society Magazine, February 1920, 80, reports: “One of the vitally interesting features of this service was the honor shown by President Grant and his associates to Sister Sarah Jenne Cannon who, as wife of President George Q. Cannon, and therefore his sole representative, honored herself and the occasion as well as her great husband in the acceptance of the marks of respect shown her. She not only sat upon the stand . . . but she was invited to speak during the services and above all was mentioned by President Grant in his dedicatory prayer.”

[30] See Waddoups, journal, 27 November 1919, 82.

[31] See Clawson, “Impressive Dedicatory Service and Prayer in New Hawaii Temple.”

[32] See Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 9.

[33] Clawson, “Impressive Dedicatory Service and Prayer in New Hawaii Temple,” 9.

[34] Joseph F. Smith, “A Dream That Was a Reality,” Improvement Era, November 1919, 16–17. The introduction to this dream reads, “President Smith recorded this testimony on April 7, 1918, of a dream which he had received.” Of where this dream occurred, the article records, “I was alone on a mat, away up in the mountains of Hawaii.”

[35] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 9.

[36] Waddoups, journal, 27 November 1919.

[37] Cassandra Debenham Bailey, remembrances by Lisa Payne, 27 November 1919, Lahaina First Ward, CHL.

[38] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 9.

[39] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 13.

[40] See “Dedication of the Hawaiian Temple,” Relief Society Magazine, February 1920, 81.

[41] See William Kauaʻiwiulaokalani Wallace III, “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Hawaiian Islands from 1850–1900,” Lāʻie Third Ward, Lāʻie Hawaiʻi Stake fireside, 30 January 2000. See also Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011), 45, quoting Frederick Beesley, “Conference,” Deseret News, 11 May 1887, 266.

[42] This was likely due to the shift in dedication dates in the preceding weeks. Word was initially sent out that the dedication would be Sunday, 30 November. That date was later moved to 27–29 November, with the mission conference to be held on 30 November. However, the events on 29 and 30 November were then likely switched (mission conference moved to Saturday and final sessions of temple dedication moved to Sunday) to ensure that anyone who had made plans for the original date of the thirtieth, or may not have learned of the change in date, would not miss the chance to attend a session of the temple dedication.

[43] See “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 6 January 1920.

[44] See Waddoups, journal, 30 November 1919.

[45] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 12.

[46] Quoted in Sheldon, “Temple Memories.” See Mary Ann Wong Soong, sacrament meeting talk on the Hawaii Temple dedication.

[47] Waddoups, journal, 30 November 1919.

[48] Waddoups, journal, 30 November 1919.

[49] Heber J. Grant to Brother and Sister Lafayette Holbrook, 8 January 1929, Heber J. Grant Collection, 55:376.

[50] Heber J. Grant to Angus Cannon, 21 March 1920, Heber J. Grant Collection.

[51] Clawson, “Dedication of Hawaiian Temple,” 1.

[52] C. W. Nibley, “True Revelation Is from God; Spiritualism Tinctured with Error,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 17 February 1920, 273–77. This address by Presiding Bishop Nibley was delivered at the Salt Lake Tabernacle, 11 January 1920.

[53] William M. Waddoups, “Personal History of William Mark Waddoups,” William M. Waddoups Papers, 1883–1969, CHL, 5.