Decision to Build a Temple in Hawaiʻi

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "A Decision to Build a Temple in Hawai'i," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 43–56.

President Joseph F. Smith and his party in front of the Laie Social Hall during their 1915 visit. From left to right: President Smith and his wife Julina, Elder Reed Smoot and his wife Alpha, Bishop Charles Nibley and his wife Rebecca, and Samuel E. Woolley. During this visit the prophet noted positive changes in the spiritual and financial well-being of the Church and improved conditions in Hawaiʻi in general. Courtesy of Church History Library

President Joseph F. Smith and his party in front of the Laie Social Hall during their 1915 visit. From left to right: President Smith and his wife Julina, Elder Reed Smoot and his wife Alpha, Bishop Charles Nibley and his wife Rebecca, and Samuel E. Woolley. During this visit the prophet noted positive changes in the spiritual and financial well-being of the Church and improved conditions in Hawaiʻi in general. Courtesy of Church History Library

President Thomas S. Monson indicated that “the ultimate mark of maturity” of the Church in any given area is the construction of a temple.[1]

Condition of the Church in Hawaiʻi in 1915

Since 1850, numerous missionaries from Utah had served in Hawaiʻi. Yet before 1900 there were seldom more than twenty-five Utah missionaries in the islands at a time, and that number increased slowly to just over forty by 1915.[2] “The success of the mission,” wrote historian Joseph Spurrier, “must be credited, in large measure, to the dedicated and devoted efforts of converted Hawaiians. These [members] served over and over again on missions, as did their children and grandchildren. Over time the names changed from Uaua, Napela, Kaleohano, Kou, Kanahunahupu, Maiola, Pake, and Puaonui to a second generation with names like Kaihonua, Kanekapu, Kealakaihonua, and Nihipali [and to a third generation with] names of Nainoa, Kekauoha, and Kalili.”[3] Hundreds of Hawaiian sisters had worked in and led the auxiliaries of the Church for years, and hundreds of Hawaiian priesthood holders had served missions, with many serving as branch presidents and in other important callings.[4]

Although the Church in the Hawaiian Islands experienced setbacks and challenges (some quite dramatic), by 1915 membership there had exceeded nine thousand.[5] As previously noted, the righteous longevity of the Hawaiian Saints had few peers among groups of Church members living outside the Intermountain West.

Not long after the Church arrived in Hawaiʻi, Native Hawaiian converts began serving missions and filling important Church leadership roles throughout the islands. By 1915 a number of those serving in the Church were third-generation members (above and on previous page).

Not long after the Church arrived in Hawaiʻi, Native Hawaiian converts began serving missions and filling important Church leadership roles throughout the islands. By 1915 a number of those serving in the Church were third-generation members (above and on previous page).

Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

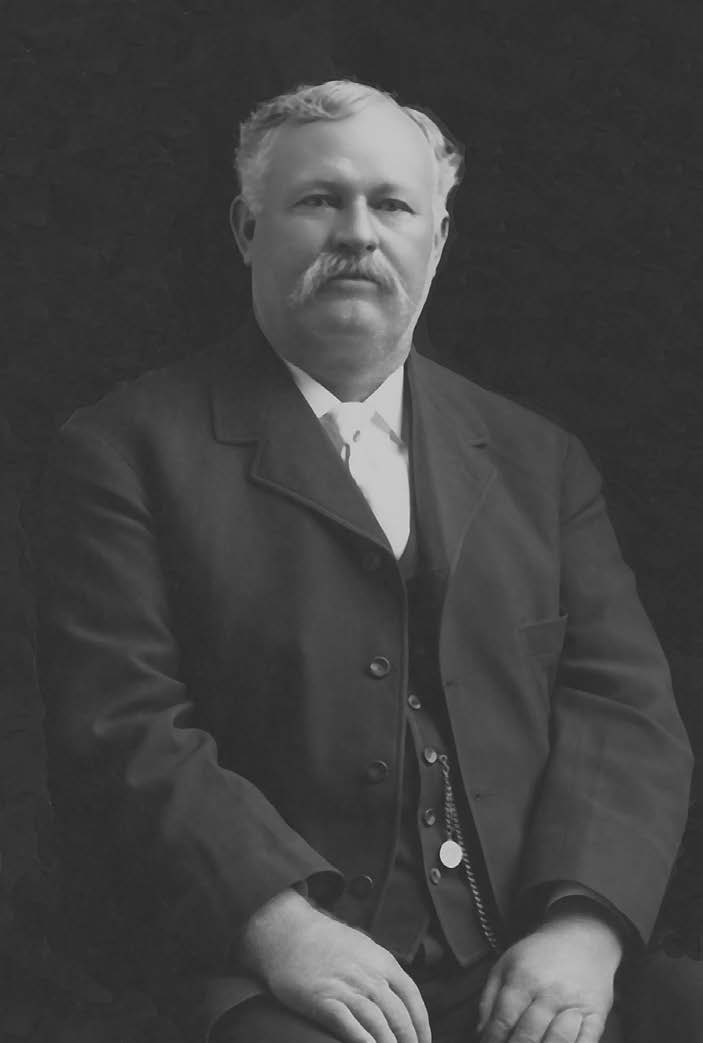

Additionally, the mission had become economically strong. In 1915 mission and plantation leadership was under the direction of Samuel Edwin Woolley. Born in Utah in 1859, Woolley was called on a mission to Hawaiʻi at age twenty, serving for a time as “cowhand” on the Lāʻie Plantation.[6] He married Alice Rowberry in 1885, and in 1890 the Woolleys were called to serve at the Iosepa colony. Then, on 9 August 1895, Samuel Woolley was called to preside over the Hawaii Mission and manage the plantation, positions he would hold for about twenty-five years.[7]

During his administration, Woolley increased productivity of the Lāʻie Plantation by buying new land, increasing the acreage under cultivation, and digging wells to satisfy the water-demanding sugarcane. When Woolley arrived in 1895, the Lāʻie sugar crop was 339 tons, and in 1918 the crop was 3,103 tons, nearly a tenfold increase.[8] During these years the plantation not only covered the needs of the Lāʻie community but also supported the financial needs of the mission, and it would substantially contribute to financing the construction of the temple.

The plantation community of Lāʻie also developed aesthetically. The additional wells provided water for the village homes, yards, and gardens. Additional trees, shrubs, and flowers were planted, and the roads were paved.[9] Yet likely the greatest contributions to Lāʻie’s environment were the wholesome lives of its residents. With rent in Lāʻie so nominal, President Woolley would say, “The price of a house and a lot at Laie is proper living.”[10] Though a relatively small portion of the islands’ Church membership lived in Lāʻie, such progress was important for a community that would become home to a house of the Lord.

Growing Anticipation of a Temple

Some had imagined a temple being built in Hawaiʻi one day, but the announcement that a temple would be built in Canada and dedication of the actual site at Cardston in June 1913 appeared to ignite a fire of possibility, particularly in President Samuel E. Woolley, that it could likewise happen in Hawaiʻi. In the following mission-wide conference in Lāʻie in April 1914, Woolley strongly encouraged the men to live worthy of the priesthood, stating, “No man has the privilege to officiate in the temple without the priesthood.”[11] During a visit to Utah later that same year, Woolley recorded that while he was attending the Salt Lake Temple, a Brother Madsen shared his impression that there would be a temple in Hawaiʻi and that Woolley would be there overseeing the people.[12]

Upon returning to Hawaiʻi in February 1915, President Woolley frequently spoke of temple work with a sense of anticipation.[13] In the April 1915 annual conference of the Hawaii Mission, Woolley told the nearly five hundred in attendance: “No temple will be built here until we keep [the law of tithing]. . . . If you want a temple in Hawaii, repent and keep this law.” He then asked, “Have we searched out our genealogies[?] Are we prepared for a temple to be built?” Then President Woolley added, “The time will come in my judgement, that a temple will be built here.”[14]

Talk of temple work was not confined to President Woolley. In the Relief Society session of the same conference, Sister Iwa Makuakane explained: “We cannot be made perfect without our dead.”[15] And Sister Sarah Jenne Cannon, the widow of President George Q. Cannon who was visiting Hawaiʻi and in attendance at the April mission conference in Lāʻie, made a financial contribution to President Woolley for a temple to be built in Hawaiʻi.[16]

President Joseph F. Smith Visits

Samuel E. Woolley was called to preside over the Hawaii Mission and to manage the Lāʻie Plantation from 1895 to 1919. During this time, Church membership doubled and plantation productivity increased nearly tenfold. Both the spiritual and monetary strength of the mission would be large factors in building a temple in Hawaiʻi.

Samuel E. Woolley was called to preside over the Hawaii Mission and to manage the Lāʻie Plantation from 1895 to 1919. During this time, Church membership doubled and plantation productivity increased nearly tenfold. Both the spiritual and monetary strength of the mission would be large factors in building a temple in Hawaiʻi.

Courtesy of Church History Library.

At the same time President Woolley was repeatedly speaking to the Hawaiian Saints of a temple, President Joseph F. Smith received an unanticipated invitation from Apostle and US Senator Reed Smoot to join him on a visit to Hawaiʻi.[17] Smoot had been invited to visit the islands as a guest of the Hawaiian Territorial Legislature and, knowing of President Smith’s affinity for Hawaiʻi, invited him to come. President Smith accepted, also inviting his good friend Presiding Bishop Charles C. Nibley to join them.

Now age seventy-seven, President Smith had “visited the Islands more throughout his life than any other destination outside of the American West.”[18] It was with anticipation that he and his wife Julina, accompanied by Bishop and Sister Nibley, traveled to Hawaiʻi for what would be a blend of respite and Church business.[19] Elder Smoot and his wife had arrived in Hawaiʻi weeks earlier, and President Woolley and the Hawaiian Saints had been notified of President Smith’s impending arrival and were eager and well prepared to receive them.[20]

Compared with the dedication of the Alberta Temple site two years earlier, and much as it is done with temples today, the sequence involved in dedicating the Hawaii Temple site was almost completely inverted. The Alberta Temple was first approved at the highest levels of the Church, then announced in general conference. Later the actual site was identified, and after a well-planned ceremony the land was dedicated. In contrast, after a few days in Hawaiʻi, President Smith—in discussion with only the mission president and Presiding Bishop—determined to build a temple, chose a site, and dedicated the land in a private ceremony involving only himself, one Apostle, and the Presiding Bishop. Then, upon President Smith’s return to Salt Lake City, approval of the temple was sought in the highest Church councils, with a formal announcement and ratification coming months later in general conference.

Although conditions in Hawaiʻi were favorable for building a temple, the record indicates that President Joseph F. Smith did not go to Hawaiʻi in 1915 with the intent of dedicating land for the construction of a temple. Further, the uncertainty of world conditions (World War I and its related events)[21] would likely have given pause to any major decision at Church headquarters. Assuming that President Smith did not go to Hawaiʻi with the intention of dedicating a temple site, it is worth considering what happened during his visit that led to his decision to do so.

Arriving at the Decision

Member hospitality and display of devotion

Numerous Saints greeted President Smith and his party, smothering them with leis as they disembarked in Honolulu on Friday, 21 May 1915.[22] The honored guests were conducted to the Honolulu district mission house, where even more Saints waited, including “Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi. For days she had been coming to the mission house and waiting on the steps[23] for the prophet, whom she had cared for when he was an ill teenage missionary some sixty years earlier. Of the prophet’s reception Elder Reed Smoot later recorded: “Talk about people loving a man! I do not believe it is possible for human beings to love a man more than did the natives of the islands love President Joseph F. Smith. . . . When he landed at Honolulu, on his arrival at the mission house, there stood in the front door President Smith’s native ‘mamma,’ blind, but oh, what a greeting there was. No mother and son ever met with greater manifestations of love for each other.”[24]

After a night’s rest in Honolulu, the President’s party traveled to Lāʻie, on the other side of the island. As they drove up the road in the early afternoon, they were greeted by four hundred Saints singing “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet.” After shaking hands with everyone present,[25] they enjoyed a musical program and a banquet that President Smith pronounced to be “the most extensive, elaborate and bounteous feast that I have ever attended.”[26] It has been said that “sharing food [in Polynesia] is a way of saying ‘here, take this food that you may have life and health.’ Without the gift of food, words of love are often empty. With the gift, words are unnecessary.”[27]

Upon retiring to the mission home, Edwin W. Fifield, clerk for the Hawaiian Mission, recorded, “As night came on the Saints gathered on the lawn under the trees in front of the mission home, ‘Lanihuli,’ and serenaded with songs and music.”[28] Of course, President Smith was no stranger to the show of such affection from the Hawaiian Saints. Yet of this day’s events Francis Gibbons wrote, “The Saints outdid themselves in hospitality and gourmandism.”[29] Such marvelous displays of Hawaiian member devotion would permeate the prophet’s visit.

Observed progress

President Joseph F. Smith and his party in Honolulu on 21 May 1915. Front row, right to left: Julina and

President Joseph F. Smith and his party in Honolulu on 21 May 1915. Front row, right to left: Julina and

Joseph F. Smith; Charles W. Nibley and his wife Rebecca. Back row, right to left: Mission president Samuel E. Woolley, Honolulu District leader Earnest L. and his wife Theresa Minor, Elder Reed Smoot, and missionaries. Courtesy of Church History Library.

President Smith’s observation of and experience with the Hawaiian Islands exceeded six decades. Yet by his own account of this visit, several things had significantly changed. Within days of his arrival, he wrote with apparent surprise that “this little portion of the world is moving along the lines of modern advancement,”[30] and he marveled at improvements in travel and communication.[31] More specifically, President Smith wrote that the “saints in Hawaiʻi . . . are apparently in vastly better temporal conditions than I have ever seen them in before,” and he noted the plantation’s “good promise and prospect for continued prosperity.”[32] Most importantly, he observed that “every indication points to the belief that they [the Hawaiian Saints] have made excellent spiritual progress.”[33] One such indication he noted was that in the more established branches “a large majority of the Saints keep the Word of Wisdom, and observe the law of tithing.”[34]

Woolley’s importuning

It appears that President Woolley was not averse to pressing the prophet to build a temple in Hawaiʻi. Henry and Abigail Florence were serving missions in Hawaiʻi during President Smith’s visit, and Abigail resided in the mission home, where the prophet’s party and President Woolley were staying. Henry later recorded: “Abigail enjoyed a very nice experience when President Joseph F. Smith, accompanied by Sister Smith and other persons, came to visit the mission. . . . While there, President Woolley, using his Hawaiian technique, pressured the Prophet into dedicating the location for the building of a temple, which President Woolley had long envisioned and saved revenue to build.”[35]

President Smith (at left, greeting two men) and his party were warmly welcomed throughout

President Smith (at left, greeting two men) and his party were warmly welcomed throughout

their stay in Hawaiʻi. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In light of today’s established procedures for requesting a temple, President Woolley’s pressing the prophet on this matter may appear overbearing. However, at that time there was no understood procedure for requesting a temple, and Woolley’s boldness is perhaps understandable. By this time Woolley had been president of the Hawaii Mission for twenty years, and he and President Smith were well acquainted and conversed regularly about the mission’s needs and progress.[36] For fifteen years Woolley had guarded President Cannon’s stated belief that a temple would be built in Hawaiʻi, and now a temple was being constructed in Canada to meet needs similar to those faced by members in Hawaiʻi. Furthermore, Woolley’s experience in the Salt Lake Temple six months earlier and Sister Cannon’s donation less than two months before appear to have strongly impressed him with the idea of a temple in Hawaiʻi. And presciently, Woolley had long been preparing the people both spiritually and temporally for such a day.

Yet regardless of Woolley’s urging, the decision was clearly the prophet’s to make under direction of the Lord. Furthermore, the idea of a temple in Hawaiʻi was hardly new to Joseph F. Smith, who himself had spoken of the possibility thirty years before. The remaining question seemed to be whether it was Lord’s will that a temple be constructed at this time. Woolley appears to have provided strong reasons in hopes that the prophet would seek confirmation from the Lord.

Funeral of Peter Kealakaihonua

Another factor that may have further contributed to consideration of a temple during this visit was the sudden passing of Peter Kealakaihonua, “one of the oldest and most respected members of the Church . . . [who] had been the means of converting a large number of islanders.”[37] At the funeral in Honolulu, Elder Smoot and then President Smith “spoke of the resurrection and the work for the dead.”[38] Later Elder Smoot recorded: “After the funeral services last Saturday I told Sister Smith and Sister Nibley as we were going to the grave yard that the church ought to erect an Endowment House or Temple at Laie so that islanders could secure their endowments and do temple work for the living and the dead.”[39] Though it does not appear Elder Smoot discussed this impression directly with President Smith nor with Bishop Nibley, it is intriguing to consider that it may have been communicated to the prophet and Presiding Bishop through their wives. Regardless, this impression clearly strengthened Elder Smoot’s resolute support when three days later the prophet would present the idea of a temple for his approval.

Financial resources

During his 1915 visit to Hawaiʻi, the prophet noted significant temporal progress and extolled the spiritual strength of the island Saints. President Smith (at center), with traveling party to the right and Samuel E. Woolley to the left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

During his 1915 visit to Hawaiʻi, the prophet noted significant temporal progress and extolled the spiritual strength of the island Saints. President Smith (at center), with traveling party to the right and Samuel E. Woolley to the left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

On return to Lāʻie, President Smith, Elder Smoot, and Bishop Nibley stopped in Kahuku to meet with a prominent sugarcane executive and discuss options for milling the Lāʻie Plantation’s sugarcane.[40] Though results of the meeting were inconclusive, consideration of business matters during their visit involved careful study of the finances and productivity of the Lāʻie Plantation, a major source of income for the Hawaii Mission. This is important because at some point before the prophet’s decision to dedicate the temple site, Bishop Nibley assured him that the Hawaiian Mission was in such financial condition that it could afford to build a small temple, and Bishop Nibley even recommended the site where such a temple might be located.[41]

President Joseph F. Smith’s well-considered yet impromptu decision to dedicate the temple site during his 1915 visit to Hawaiʻi involved a mosaic of compelling reasons and sound conditions. His firsthand observation of temporal and spiritual improvement among the island Saints, contemplation prompted by the death of a beloved Church member, assurance of the mission’s financial stability, and bold reasoning of President Woolley—all wrapped in repeated displays of Hawaiian member devotion—seem to have provided the right conditions. No doubt President Smith, who intimately knew and loved these people, had always hoped for this day, but now it appeared that building a temple was feasible and would meet with the Lord’s approval.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Richard O. Cowan, “Joseph Smith and the Restoration of Temple Service,” in Joseph Smith and the Doctrinal Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 109–22.

[2] See R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018), 232.

[3] Joseph H. Spurrier, Sandwich Island Saints: Early Mormon Converts in the Hawaiian Islands (Oʻahu, HI: Joseph H. Spurrier, 1989), 60.

[4] See R. Lanier Britsch, “The Conception of the Hawaii Temple,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 9, no. 1 (1988), https://

[5] See Britsch, Moramona, 227.

[6] See Spurrier, Sandwich Island Saints, 59.

[7] See Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011), 77–78. See also Britsch, Moramona, 211–19; and Lance Chase, “Samuel Edwin Woolley: An Appreciation in Temple Town, Tradition,” The Collected Historical Essays of Lance D. Chase (Lāʻie, HI: Institute for Polynesian Studies; Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 2000).

[8] Britsch, Moramona, 218–19.

[9] Britsch, Moramona, 228. See W. K. Bassett, “Civic Pride Is Part of Mormon Policy as Evidenced by Settlement at Lāʻie: Homes, Roads and School Are Credit to the Territory,” Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Sunday, 21 March 1920.

[10] Quoted in Britsch, Moramona, 229. See Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), general minutes, 6 April 1911. See also Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 82; and Samuel E. Woolley, “Minutes of the annual conference of the Hawaiian Mission,” 6 April 1911, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), 8.

[11] History of the Hawaiian Mission, 4 April 1914.

[12] Samuel E. Woolley, diary, 2–4 December 1914, CHL.

[13] Woolley, diary, 28 February 1915 and 20 March 1915, CHL.

[14] Hawaiian Mission conference minutes, 4 April 1915, LR 3695 32, CHL, 5–9, https://

[15] Woolley, diary, Relief Society session of conference, 5 April 1915, CHL.

[16] John A. Widtsoe, “The Temple in Hawaii: A Remarkable Fulfilment of Prophecy,” Improvement Era, September 1916, 956.

[17] Harvard Heath, ed., In the World: The Diaries of Reed Smoot (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997), 7:262.

[18] Richard J. Dowse, “The Laie Hawaii Temple: A History from Its Conception to Completion” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2012), 58, https://

[19] See Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 308.

[20] An entry in History of the Hawaiian Mission, 3 May 1915, reads: “Apostle Reed Smoot, U.S. Senator, and wife, arrived in Hawaii.” Samuel E. Woolley’s diary entry for 10 May 1915 (p. 317) notes the following: “Organized committees to prepare for visit by President Smith.”

[21] See Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 307: “The prophet expressed his shock at the sinking of the Lusitania on May 8 [1915] and the loss of over thirteen hundred among the crew and passengers. . . . The following day [9 May] the prophet and his party departed for still another trip to his Hawaiian Islands.”

[22] See Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 309; and History of the Hawaiian Mission, 21 May 1915.

[23] See Isaac Homer Smith, in Brief History of the Life of Isaac Homer Smith, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI.

[24] Reed Smoot, in Conference Report, October 1920, 137.

[25] See Edwin W. Fifield, “Pres. Smith’s Party Visits in Hawaii,” Deseret Evening News, 12 June 1915. See also Heath, Diaries of Reed Smoot, 227.

[26] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 309.

[27] Eric B. Shumway, president of Brigham Young University–Hawaii from 1994 to 2007, statement in authors’ possession.

[28] Fifield, “Pres. Smith’s Party Visits in Hawaii.”

[29] Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 309.

[30] President Joseph F. Smith to President Hyrum M. Smith, Lanihuli, Lāʻie, Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, 27 May 1915, Millennial Star, 8 July 1915, 418.

[31] See Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 309.

[32] President Joseph F. Smith to President Hyrum M. Smith, 418.

[33] President Joseph F. Smith to President Hyrum M. Smith, 418.

[34] Fifield, “Pres. Smith’s Party Visits in Hawaii.”

[35] Quoted in Elsie A. Florence, comp., Henry Samuel and Elsie Dee Adams Florence (Salt Lake City: E. A. Florence, 1987), CHL. That President Smith discussed the matter of a temple with Woolley before he dedicated the site is substantiated in Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 26 October 1915, 275. See “Conference Address by President Joseph F. Smith,” Millennial Star, 4 November 1915, 694.

[36] Woolley’s journal records yearly trips to Utah (sometimes more often), where he would visit directly with President Joseph F. Smith.

[37] Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 6 July 1915, 24. See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 27 May 1915.

[38] Reed Smoot, diary, 29 May 1915, Reed Smoot Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[39] Heath, Diaries of Reed Smoot, 273–74.

[40] See Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith, 310.

[41] See Heath, Diaries of Reed Smoot, 273.