Cultural Center and Temple Complex Expanded—1960s

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Cultural Center and Temple Complex Expanded—1960s," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 281–308.

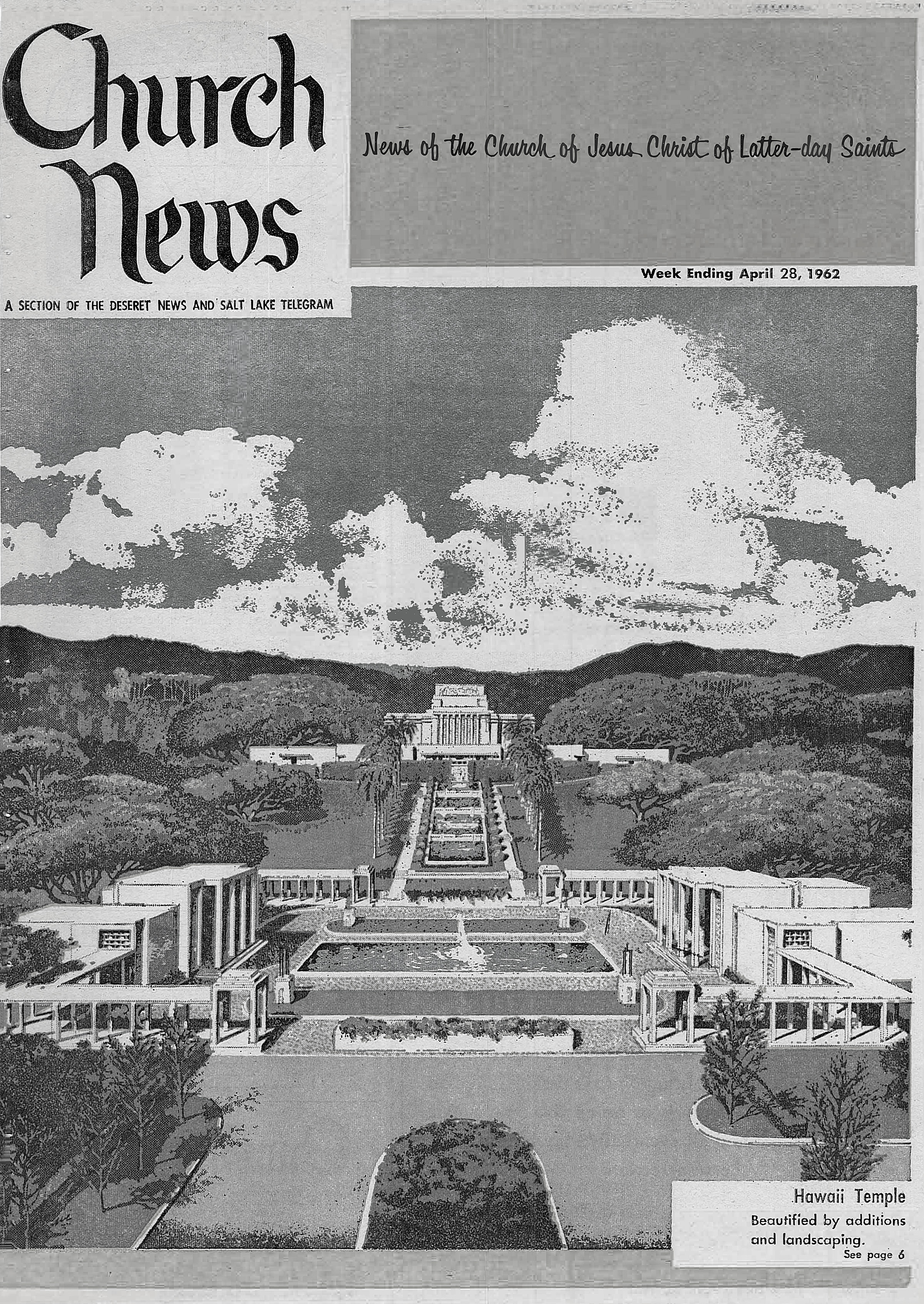

This cover illustrates the plan for the Hawaii Temple and its grounds, improvements that would coincide with additions made to the college and with the construction of the Polynesian Cultural Center. Courtesy of Church News.

This cover illustrates the plan for the Hawaii Temple and its grounds, improvements that would coincide with additions made to the college and with the construction of the Polynesian Cultural Center. Courtesy of Church News.

As the Church College of Hawaii grew, it was soon apparent that the original campus buildings and facilities would not adequately accommodate the expanding student enrollment.[1] To meet this need the college construction program, with its use of building missionaries, was reactivated from 1960 to 1963. These years of construction resulted in not only additions to the college but also construction of the Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC) and the most extensive additions and renovation that the Hawaii Temple complex had ever undergone.

Temple Renovations

Ordinance work in the Hawaii Temple had been increasing since the end of World War II, and early progress of the Church College, Hawaiʻi’s recent statehood, and continued growth of the Church in Hawaiʻi all bolstered optimism about the temple’s further success. Thus the decision to expand the college was seen as an opportune time to expand the temple as well.

Now age seventy-two, Harold W. Burton, the temple’s original architect, made a careful study of the structure to ensure that any addition would not detract from the temple’s original beauty. He designed additions that extended in long, low lines at the sides and base of the temple. Thus rather than detracting from the temple’s beauty, the additions emphasize the original gemlike structure, allowing it to rise above its newer features against a backdrop of mountain scenery.[2] The additions expanded the temple annex to 270 feet, nearly double its previous length,[3] and included additional office space, dressing room facilities, a bride’s room, and a lounge. Further renovation produced a new laundry, a children’s waiting room, and a new washing and anointing room for the women.[4]

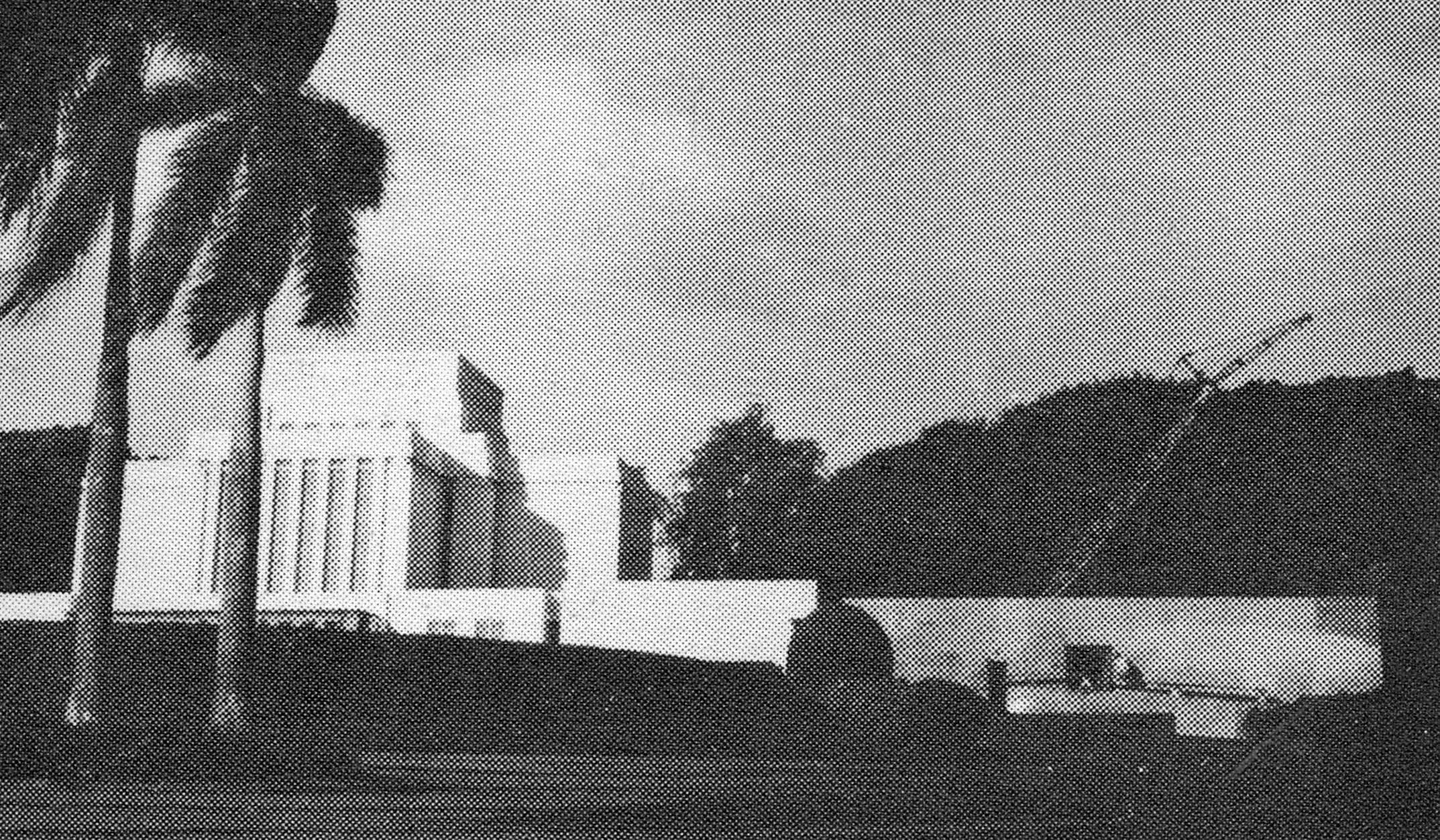

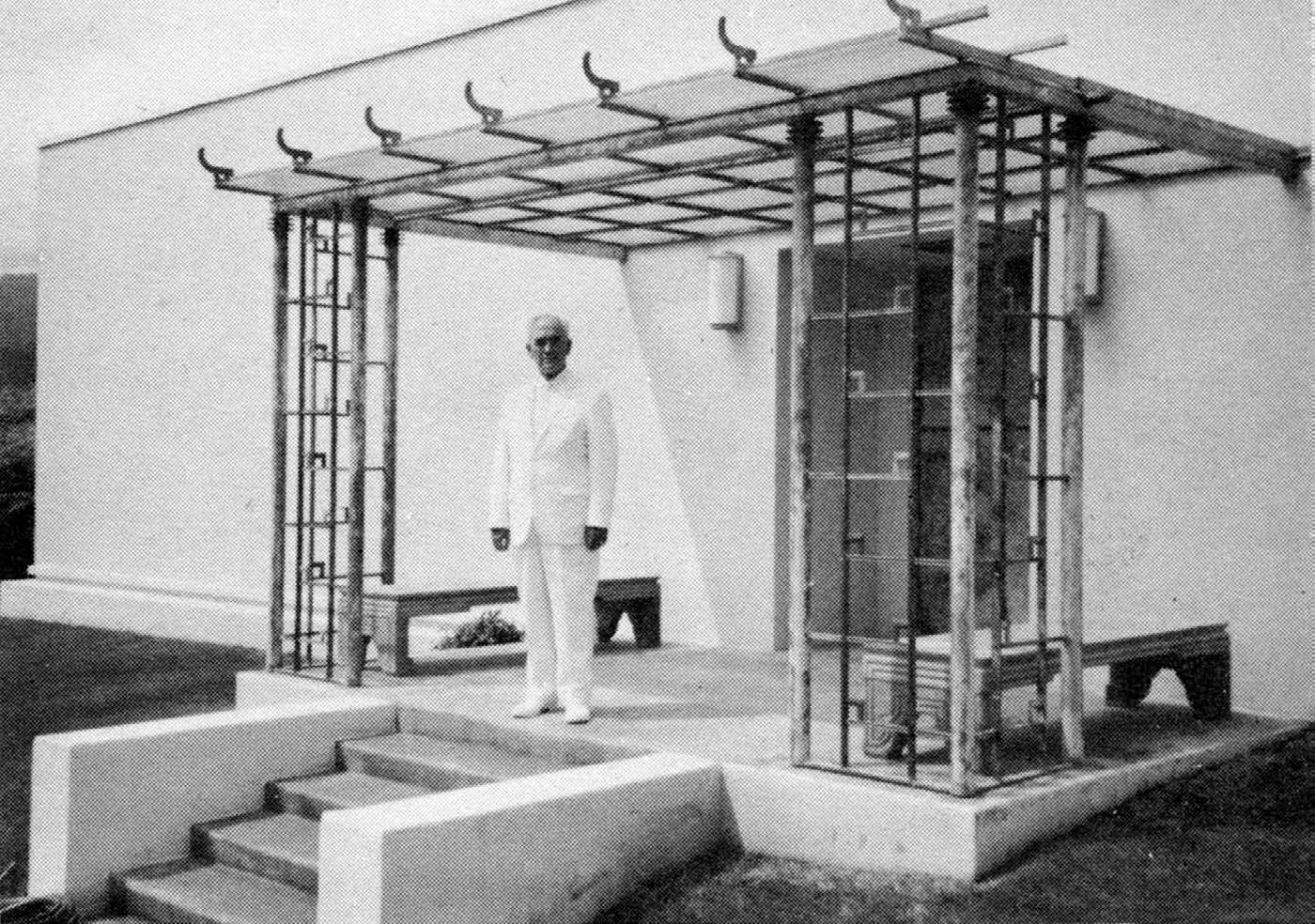

Extending in long, low lines at the sides and base of the temple, the 1960–63 additions sought to emphasize the original gemlike structure and nearly doubled the length of the temple annex. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Extending in long, low lines at the sides and base of the temple, the 1960–63 additions sought to emphasize the original gemlike structure and nearly doubled the length of the temple annex. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

During this construction, President H. Roland Tietjen toured the temple with Douglas W. Burton (the on-site architect and the son of Harold W. Burton) and saw fit to propose additional projects, including repairing walls, installing new lockers, retiling the baptismal font, refurbishing exterior windows, replacing furniture, recarpeting the celestial room, redecorating sealing rooms, and installing a new recommend desk.[5] Surprisingly, the temple remained open during most of this work because some of the more intrusive construction was done during the temple’s regular summer and Christmas season closures.

Also in the temple plan was the construction of a temple president’s home and four homes for the temple guides. Ground just north of the temple was cleared of various structures and leveled for the construction of these homes.[6] Sadly for a number of longtime Church members, one of those structures removed was the Lanihuli home. A landmark for more than sixty-five years, Lanihuli had served as the Hawaii Mission headquarters, accommodated multiple prophets and other General Authorities, provided temple housing, and finally served as a girls’ dormitory for the college. Yet the additions and improvements to the temple complex were overwhelmingly welcomed by the Saints there. “The temple is greatly improved with the new construction,” wrote President Edward L. Clissold in 1963. “It is a restful and joyous experience to be there.”[7]

The Tongan and Samoan building missionaries attended the temple to receive their own endowments and regularly attended the temple during their service. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The Tongan and Samoan building missionaries attended the temple to receive their own endowments and regularly attended the temple during their service. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

All this construction—on the college, the temple, and the Polynesian Cultural Center—was done by building (labor) missionaries. This second phase of the construction program in Lāʻie (1960–63) involved 70 missionaries from the mainland and 123 from across the Pacific.[8] One of the blessings the Tongan and Samoan building missionaries looked forward to when called to Hawaiʻi was going to the Hawaii Temple for their own endowments (missionaries from New Zealand had already attended the temple). On 3 May 1960, 47 of them entered a house of the Lord for the first time. At that point, this was the largest number of endowments for the living ever done in the Hawaii Temple in one session.[9] Reflecting on his time spent in Lāʻie, one labor missionary said, “The most memorable thing that ever happened [was] when all the labor missionaries went and had their temple endowments taken out. . . . The workers in the temple that day seemed to just have been there for us. It was a very memorable occasion.”[10] In succeeding months, the remaining members of the Tongan-Samoan building missionary group went to the temple for their endowments. Eight of the Tongan building missionaries who were married were able to have their families join them while serving in Lāʻie, thus providing them the blessing of being sealed in the temple.[11]

What’s more, a number of the building missionaries were called as temple workers. With such a large number of building missionaries eligible and eager to do temple work, the temple presidency created a monthly session especially for these missionaries. Of this recurring session and the overall contribution to temple work by the building missionaries, Alice Pack wrote, “This was a wonderful privilege to meet as a group, who in daytime united in building God’s physical kingdom, but could on this sacred evening combine their efforts in the work of His spiritual kingdom.”[12]

The Polynesian Cultural Center and the New Temple Visitors’ Center

The additions and renovation to the temple proper and the new temple housing were important contributions on their own. However, the most striking addition to the temple complex during these construction years was an expansive new visitors’ center. As noted, the temple had been extraordinarily successful in drawing visitors throughout its first forty years of operation, and expanding the old Visitors’ Bureau was well justified.[13] However, an unexpected sequence of events would end up producing a visitors’ center suited to a future that few could have imagined at that time. Further, the story of the new visitors’ center and its ensuing success connects with the early need for temple housing and is interwoven with the Polynesian Cultural Center.

Genesis of the PCC

At the start of the Church College of Hawaii’s second year, its president, Reuben D. Law, emphasized that “one of our great needs . . . is for part-time job opportunities near enough to our students so they may work while attending school.”[14] The answer to that need—the PCC—found its beginnings linked to the temple. The result has brought literally millions of visitors to the temple grounds.

The Samoan families who relocated to Lāʻie in the 1920s to be near the temple needed to support themselves. While a number of them found work on the plantation, others made and sold handicrafts to tourists who came to see the temple. Connected with this enterprise was a replica Samoan village constructed by the Toa Fonoimoana family. With the addition of food and entertainment, this replica village “became a tourist destination on its own, as a display of Samoan life and culture.”[15]

In 1951, while discussing the lack of lodging in Lāʻie for temple patrons from the Pacific, Elder Matthew Cowley of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and President Edward Clissold of the Oʻahu Stake considered ideas that led to the creation of the Polynesian Cultural Center. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In 1951, while discussing the lack of lodging in Lāʻie for temple patrons from the Pacific, Elder Matthew Cowley of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and President Edward Clissold of the Oʻahu Stake considered ideas that led to the creation of the Polynesian Cultural Center. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Then in 1951, while considering the lack of lodging in Lāʻie for the Māori Saints who came from New Zealand to attend the temple, Apostle Matthew Cowley suggested that a whare (Māori house) in Lāʻie might solve the problem. He further suggested the visiting Māori might support themselves during their stay by singing and dancing for tourists. Of this idea, Edward Clissold observed, “If that’s true of the Maori people, it could also be true of the other people who come up [to the temple].”[16] And shortly thereafter Elder Cowley, in the Oʻahu Stake conference, said, “I can envision a time when there will be [Polynesian] villages at Laie. They’ll have a carved house . . . for the Maoris, a Samoan village, a Tahitian village, and villages for other peoples of the South Seas.”[17] Sadly, Elder Cowley died in 1953, but his idea endured.

Lending support to the viability of this idea, the community of Lāʻie had for years found financial success in its hukilau, which involved tourists paying to spend a day on the beach in Lāʻie fishing with nets, feasting, and being entertained Polynesian-style.[18] Furthermore, Latter-day Saint businessman George P. Mossman had proved in the 1930s that a replica Hawaiian village with live demonstrations in Waikīkī could be successful.[19] And under the direction of Professor Wylie Swapp there was the burgeoning success of a student entertainment group from the Church College of Hawaii performing in Waikīkī.[20]

Thus as the Church College board (of which Edward Clissold was chairman) wrestled with the need for part-time student employment nearby, the idea for the PCC percolated to the top. The center would take the shape of six Polynesian villages, each village a small cluster of typical houses, shelters, and buildings particular to a different island country. Guests could stroll through the villages and experience the language, history, arts, crafts, games, and activities of the various island cultures.[21] Also, summarily affixed to the center’s purpose in its dedicatory prayer is that it would radiate “[God’s] honor and glory.”[22]

Design and construction of the visitors’ center

It was eventually determined to build the Polynesian Cultural Center next to the temple (on the south side, toward the college). It was felt that tourists would not make two stops in Lāʻie and that, once conjoined, neither the temple Visitor’s Bureau nor the PCC would suffer any negative impact. It was also felt that because the temple consistently drew tourists, this allure could not help but benefit the PCC. Further, temple parking could be expanded to provide easy access to both venues, and the location was convenient for students as well.[23]

Building missionaries constructing the temple’s new Bureau of Information. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Building missionaries constructing the temple’s new Bureau of Information. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

With the site chosen and preliminary approval given, Harold Burton was asked to make a new sketch showing the desired location for the PCC in relation to the Visitors’ Bureau parking space. This request had a far-reaching effect. Burton pointed out that the PCC would increase the flow of tourists to Lāʻie to a degree that would make necessary an enlargement of the Visitors’ Bureau, and he made new sketches illustrating his idea. The Church News ran Burton’s drawing of the temple with its new additions and his proposed visitors’ center on the front page of its 28 April 1962 issue along with the following report:

President David O. McKay was deeply impressed by the drawing submitted by . . . the Church building committee, and Harold W. Burton, head of the architects department, who drew the plans seen on the cover.

The new wings on either side of the temple which will provide additional space for functional requirements are nearly completed.

One of the major improvements is the bureau of information now under construction. It surrounds a new mall with a large reflecting pool at the foremost of the temple.

The bureau will have two lecture rooms, each has a seating capacity for 170 persons to care for the heavy flow of tourists.

In addition to the auditoriums the new bureau will have four rooms for use of bureau directors and additional facilities to aid directors [in] explain[ing the] Gospel to interested parties. Lecture tapes and films will be shown to visitors before guides take them from the bureau for a tour of the temple grounds.

The work is being accomplished by labor missionaries . . . called from the mainland and the Polynesian Islands of the Pacific.[24]

The new Bureau of Information was increasingly called the visitors’ center, a moniker that eventually became the official name. View of north courtyard. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The new Bureau of Information was increasingly called the visitors’ center, a moniker that eventually became the official name. View of north courtyard. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

With the old Visitors’ Bureau torn down and construction on the new visitors’ center underway, construction on the PCC commenced. The site was filled and fenced and the lagoon excavated when President McKay, in response to concerns over the PCC’s cost and its location next to the temple, appointed Elders Delbert L. Stapley and Gordon B. Hinckley to go to Hawaiʻi and make a thorough investigation. It was concluded that the PCC should not be built next to the temple for fear that the noise, traffic, and venue might detract from the temple’s sacred nature.[25] The PCC was moved to its current location on the other side of the college, toward Kamehameha Highway. And the new expansive visitors’ center, which was designed to a scale proportionate with the adjacent PCC, proceeded to completion.[26]

With the temple additions, housing renovations, and visitors’ center all complete, President Hugh B. Brown (in place of an aging President McKay) presided over the dedicatory prayer service held on the temple grounds on 13 October 1963. In his prayer Elder Brown petitioned “that all who enter here will know by the whisperings of thy spirit that they are on holy ground, and at least may figuratively remove the shoes from their feet.” He further asked “that the spirit of temple work may move among the people, that they may make the necessary sacrifices of time and means to do their temple work.”[27]

Aerial view of the temple and its new visitors’ center, circa 1962. Courtesy of David Hannemann.

Aerial view of the temple and its new visitors’ center, circa 1962. Courtesy of David Hannemann.

“A missionary factor influencing millions”

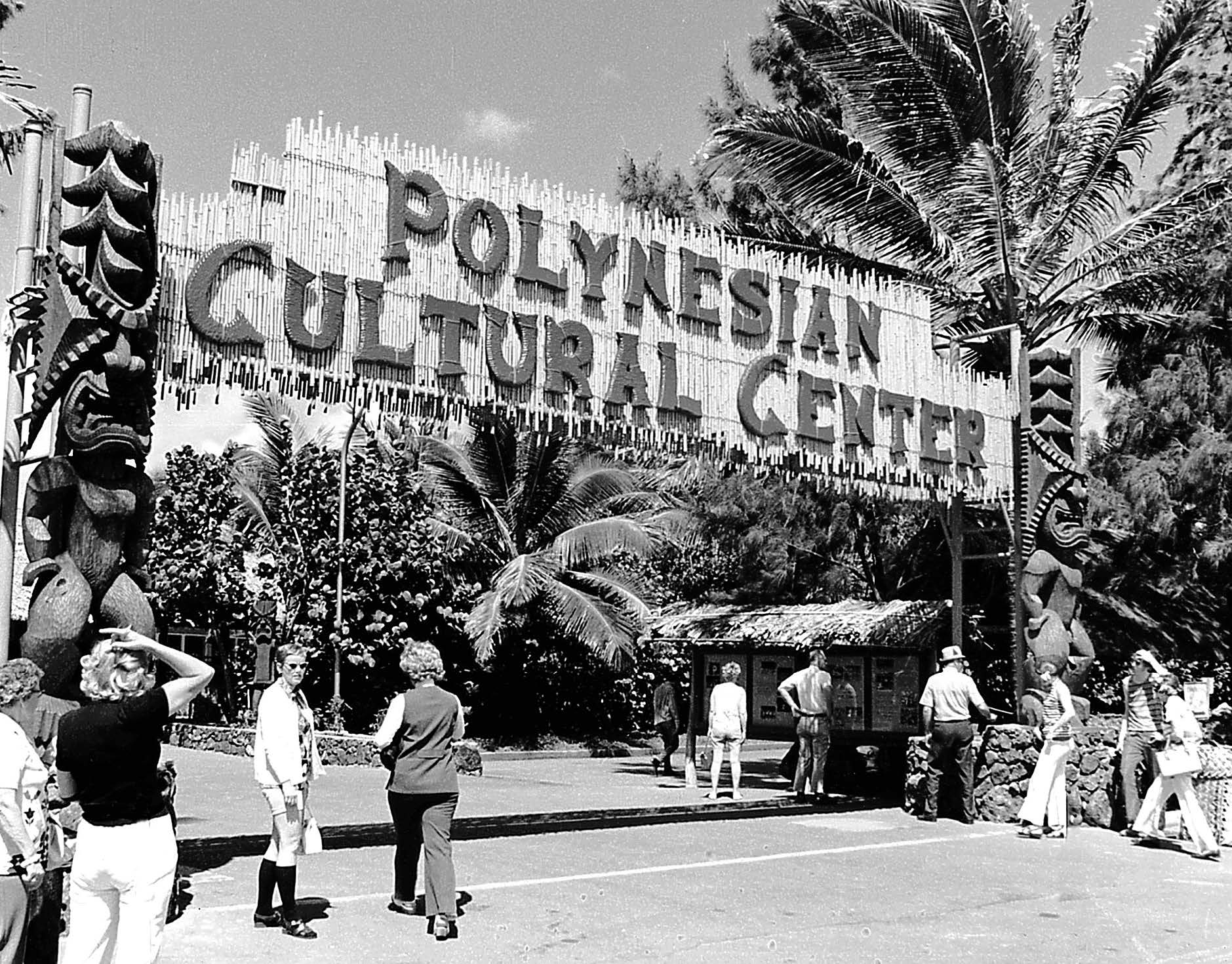

Construction was complete, yet questions lingered. Now that the structures were separated, would tourists stop at both the PCC and the temple? Would the PCC even be viable? Would the much larger visitors’ center be justified? For some time the outlook was extremely uncertain. By the end of 1963, the PCC had a net operating loss of more than sixty thousand dollars, and it experienced an even larger loss in 1964.[28] Some blamed the center for fewer visitors to the temple grounds in the year that followed its opening.[29]

Yet with determined effort and communal sacrifice the PCC persisted, eventually becoming an astonishing success. In 1967, four years after its opening, the PCC posted its first profit. Yearly attendance in 1972 exceeded one million, and by 1977 the center was the top paid attraction in the Hawaiian Islands.[30] Remarkably, the PCC has welcomed tens of millions of visitors to Lāʻie over the years, and millions of those visitors have found their way to the temple grounds.

Perhaps most noticeable in the relationship between the PCC and the temple has been the free guided tour of Lāʻie, which began in 1973. Developed by PCC staff, and originally using two replica 1910 Honolulu trams for effect, the tour has generally included a brief history of the Lāʻie Plantation, the purposes of the college, and reasons why Latter-day Saints build temples. The final stop on the tour is the temple, where participants spend time on the temple grounds and in the visitors’ center before returning to the PCC.[31]

Originally using two replica 1910 Honolulu trams for effect (pictured), the free guided tours

Originally using two replica 1910 Honolulu trams for effect (pictured), the free guided tours

of Lāʻie included the temple as a final stop before returning to the PCC. Courtesy of BYU– Hawaii Archives.

It is inspiring to consider the ongoing fulfillment of President David O. McKay’s prophetic words pronounced in a cleared sugarcane field just south of the temple in 1955—“that this college, and the temple, and the town of Laie may become a missionary factor, influencing not thousands, not tens of thousands, but millions of people who will come seeking to know what this town and its significance are.”[32] That year the college enrolled 153 students and the town had fewer than one thousand residents. And although the temple was recognized as a tourist stop on tours of Oʻahu, only about one hundred thousand tourists visited Hawaiʻi that year.[33] Then in 1963, with modest fanfare and some predictions of failure, the Polynesian Cultural Center opened its doors, and as a result tens of millions have come to Lāʻie and felt its influence. Alton L. Wade, president of BYU–Hawaii from 1986 to 1994, explained:

The temple, the school, and the cultural center work together in a dynamic way: Students lend the cultural center their exuberance, smiles, and radiant spirits, and the students’ wages from their jobs at the cultural center make it possible for many to attend school. As they walk across campus, students are blessed to see the house of the Lord rising above the palm trees, and those who enter that holy place can attune themselves spiritually and refocus on eternal objectives. And the visitors’ center near the temple attracts visitors as they leave the Polynesian Cultural Center.

Top and Bottom: Remarkably, the PCC has welcomed tens of millions of visitors to Lāʻie over the years, and millions of those visitors have found their way to the temple grounds. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Top and Bottom: Remarkably, the PCC has welcomed tens of millions of visitors to Lāʻie over the years, and millions of those visitors have found their way to the temple grounds. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Only the Lord could orchestrate a marvelous threefold effort such as this. With the temple setting the tone, the Polynesian Cultural Center will continue to fulfill its prophetic destiny as a missionary tool affecting millions, and BYU–Hawaii will continue to send its culturally diverse, academically and spiritually prepared students throughout the world.[34]

Few temples work so synergistically with other Church institutions as does the Laie Hawaii Temple. As President Howard W. Hunter succinctly observed, “This triad of learning established by the Church in Laie, namely the BYU–Hawaii campus, the Polynesian Cultural Center, and the Temple, has a significant place in the plan of the Lord to further the work of his kingdom.”[35]

Devoted Efforts of Temple Personnel

Ensuring that temple patrons enjoy a rich spiritual experience has always required consistent behind-the-scenes efforts of committed administrators, staff, and workers. President Tietjen and his wife Genevieve met regularly with temple workers, meticulously seeking to make the temple experience meaningful for all who entered. In these meetings were discussed seemingly small items, such as folding clothes most accommodatingly for patron use, arranging chairs in the baptistry so as not to get water on them, and adjusting the air conditioning. Yet the cumulative result of such attention to detail can substantially affect the patron experience and spirit of the work.

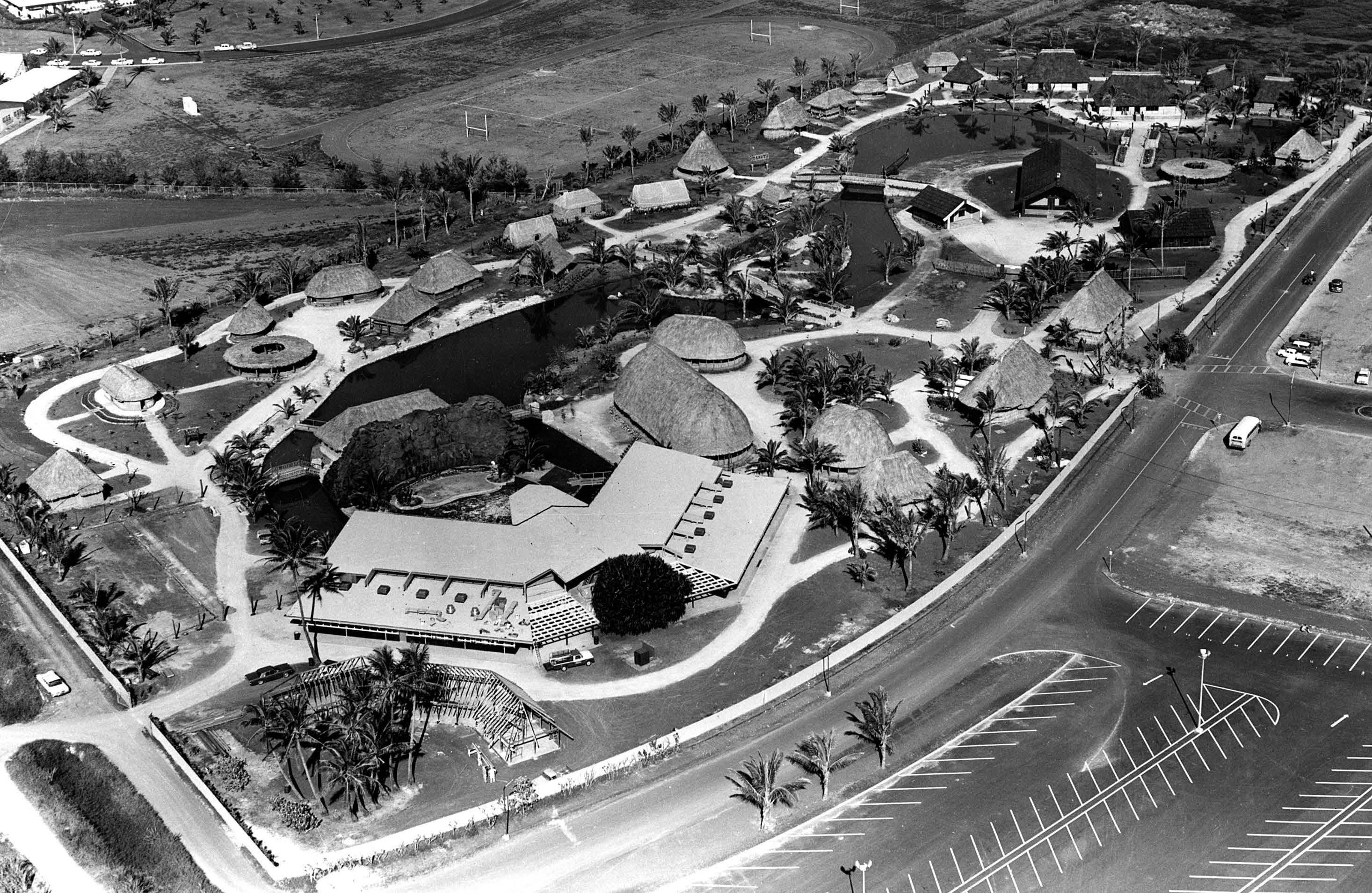

President Howard W. Hunter noted that the Hawaii Temple (lower left), Church College of Hawaii (middle right) and Polynesian Cultural Center (upper right) form a “triad of learning” that “has a significant place in the plan of the Lord to further the work of his kingdom.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

President Howard W. Hunter noted that the Hawaii Temple (lower left), Church College of Hawaii (middle right) and Polynesian Cultural Center (upper right) form a “triad of learning” that “has a significant place in the plan of the Lord to further the work of his kingdom.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

President H. Roland and Sister Genevieve Tietjen and temple workers circa 1962. Ensuring that temple patrons enjoy a rich spiritual experience has always required consistent behind-the-scenes efforts of committed administrators, staff, and workers. Courtesy of Wallace and Hilda Forsythe family.

President H. Roland and Sister Genevieve Tietjen and temple workers circa 1962. Ensuring that temple patrons enjoy a rich spiritual experience has always required consistent behind-the-scenes efforts of committed administrators, staff, and workers. Courtesy of Wallace and Hilda Forsythe family.

Larger challenges would periodically arise, requiring creative administrative solutions and adaptable workers. For example, facing a particularly large backlog of male names, in May 1960 President Tietjen, along with stake leaders, created “a special Priesthood Day of eight sessions [that] was carried out at the Temple by the Oahu and Honolulu Stakes. Four hundred seventy-five endowments for the dead were performed and a beautiful spirit prevailed.”[36] Other substantial challenges such as a monthlong lack of female names in 1962 were met with similar resourcefulness. Perhaps the highest compliment to the often silent and unseen efforts of the temple administration, staff, and workers is that most patrons don’t even need to consider such efforts but instead simply enjoy the sacred environment and ceremony within the house of the Lord.

Change in Temple Presidency and Procedures

Although the Tietjens had served three years, their release was rather sudden. In December 1962 while in Utah for the holidays, President Tietjen was taken ill and required surgery. With no definitive date for his recovery, President David O. McKay turned to his trusted friends Edward and Irene Clissold to promptly assume the Hawaii Temple presidency. President Clissold was released as Honolulu Stake president, and he and Irene moved to their home on the beach in Lāʻie.

Having served as temple president twice before, President Clissold was comfortable in his calling and almost immediately began to consider changes to improve the temple’s functionality. The first change was a division of responsibilities among the temple presidency. Although some form of sharing responsibilities had always been done, the structure and line of reporting was now formalized, and some tasks considered specific to the president were now understood to be delegable. But the two largest changes enacted under Clissold in the early 1960s were separating the initiatory from the endowment and installing an audio system for the presentation of the endowment.

Separating the initiatory from the endowment had only recently begun in a limited number of other temples. On 6 May 1963, after some room rearrangement and training of temple workers, the initiatory ceremonies were performed by themselves in the Hawaii Temple for the first time. On 14 May President Clissold recorded, “First session in 45 years without the company going to the W&A room except for the new name. Everyone seems pleased with the new procedures and especially with the new physical arrangements.”[37]

View of the Laie Hawaii Temple from the Church College of Hawaii campus. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

View of the Laie Hawaii Temple from the Church College of Hawaii campus. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Efforts to install an audio system took considerably longer. For over a year, President Clissold worked with Elder Gordon B. Hinckley and a number of technicians to make this happen. In recognition of the temple’s forty-fifth anniversary, President Clissold specifically chose 27 November 1964 for the tape’s inaugural use.[38] The use of tapes instead of actors not only ensured accuracy of the endowment but generally sped it up and allowed more accurate scheduling based on a set time. Particular in President Clissold’s desire to acquire the use of tapes was the chance to offer the endowment in other languages. Just over three months after the first use of English tapes, President Clissold rejoiced: “First session in Samoan language tonight. Tears all around us. Some of these faithful old people understood the ceremonies for the first time.”[39] Perhaps sooner than anyone expected, Japanese tapes were used just five months after that.

President Clissold’s Release

From 1963 to 1965, President Clissold served as temple president, spent countless hours willing the PCC forward, attended to the needs of the Church College and Pacific Board of Education, worked with Zions Securities, and commuted two to three days a week to Honolulu for his job. He admitted in his journal that these years were the busiest and most pressure-filled years of his life. In the month following the departure of Japanese members on their temple excursion (see chapter 17 herein), he spent five days in the hospital because of a heart condition. After returning from the hospital, he and Irene moved from their home on the beach to the temple president’s home to be closer to the temple. Days later he recorded, “113 in the 10 o’clock session, largest in the history of the temple. 31 new people, 11 sealings. Crowded but a beautiful session.” Less than two weeks after that, he learned of his and Irene’s release as president and matron of the Hawaii Temple.[40]

Years later Clissold shared an experience he had during his third term as Hawaii Temple president:

I was sitting in the temple one morning [and] looked down over the pools and down the approach to the temple to the highway.

As I sat there . . . I saw a line of people, extending down the walks on both sides of the pools, down . . . to the highway, and along the highway. These people were lined up close together, and they had little suitcases. Some were sitting upon them, and some were holding them, some had them at their side. But the line was moving very, very slowly.

. . . A few weeks later, Elder Harold B. Lee was here. . . . I told him I had imagined a scene that I couldn’t forget. . . . He said, “Brother Clissold, I believe that was a vision given to you as president of the temple, to impress upon you the importance of temple work and the fact that there are many, many thousands of people that are waiting for these ordinances.” . . . This view became more and more important to me as I strived to do the work. . . .

Brothers and sisters, as we go to the temple, as we contemplate the gospel and its great meaning in our lives, if we remain the same we haven’t been touched. If we change for the better, we have. We should seek for that change and that guidance which will carry us on to the goal for which we all labor.[41]

Edward L. Clissold’s third call as temple president came at a particularly dynamic and need-filled time in Lāʻie’s history. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Edward L. Clissold’s third call as temple president came at a particularly dynamic and need-filled time in Lāʻie’s history. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In hindsight, Clissold’s third call as temple president in early 1963 was markedly providential. This call put him in Lāʻie at a particularly dynamic and need-filled time in its history. The construction and building missionary programs were in their final year, and the PCC desperately needed his vision and determined oversight. He did much to help move the temple into the technological age and was uniquely qualified to oversee one of the most successful temple excursions (from Japan) in the temple’s history. It seems clear that his third calling as Hawaii Temple president was “for such a time as this” (Esther 4:14).

Community Members Act as Guides on the Temple Grounds

Harry V. and Louise Brooks were called as president and matron of the Hawaii Temple in October 1965—a calling they would fill for seven years. President Brooks had served a mission to Hawaiʻi (1929–31) and was later called as Hawaii Mission president (1958–64). He and Louise were serving as missionaries at the Hawaii Temple Visitors’ Center when they were called to preside over the temple.

The incredible success of the temple visitors’ center, with its often unpredictable flood of visitors (sometimes several hundred at a time), had long caused a conundrum over how to properly assist so many visitors with so few missionaries. So for years, in both formal and informal ways, local members had pitched in to help as guides. However, while serving as missionaries at the temple Bureau of Information, the Brookses helped enlarge and formalize the community guide program to accommodate the ever-growing number of visitors to the temple grounds. “Nearly 250,000 visitors will pass through the temple grounds this year,” President Brooks told a Honolulu newspaper. “During the summer [1965] 75 guides gave their time to supplement the work of full-time missionaries assigned to the bureau.”[42] Community member Charles Goo recalled:

While I was in high school I used to just love coming up to the temple and helping as a tour guide. Because my father’s store was just kitty-corner [to the temple], I could see the tour buses pull up, and sometimes the parking lot was filled with them. . . .

. . . In those days the guides took tours up and around the temple, even to the back, and explained the friezes on the top of the temple. . . . They were all kinds of people from all over the world. . . . I remember . . . introducing them to the gospel, sharing the First Vision, everything. . . .

I didn’t have any specific shift, but just when I saw the need and there was enough help at the store, I would just put on my white shirt and tie, and . . . just come up and assist.[43]

Eventually guidebooks, training, and weekly schedules were created for the community volunteers (which included BYU–Hawaii students). Speaking to the possibilities of such service, the preface to one of these guidebooks read: “To be called as a guide at the temple grounds is a great honor and privilege. It is missionary work at its finest. We who have served as guides in the past can bear testimony of the fruits of our labors there. The lives of tens of thousands of people have been changed as a result of the few impressionable minutes they have spent on the temple grounds with an enthusiastic, spiritual guide.”[44] This community guide program continued in various forms for years, eventually evolving into the work of the numerous full-time sister missionaries seen at the visitors’ center today.

Project Temple

Just months into the Brookses’ tenure as temple president and matron, it was noted that in the first two months of 1966, “21 previously married couples received their own endowments and were sealed as husband and wife for time and all eternity and their children were also sealed to them.”[45] Similarly, five previously married couples received their endowments and were sealed as families in March, thirteen in May, seventeen in September, and eighteen in November. By the end of 1966 more than one hundred previously married couples had received their endowments and been sealed as families. These unusually high numbers continued over the next couple of years. This increase was largely attributed to members’ implementation of a program called “Project Temple.”[46]

A stake in Utah had formalized a program for preparing previously married but unendowed couples to enter the temple and ultimately be sealed as families. The idea was to give these members “projects to accomplish, and when they accomplished them they would be ready for the temple.”[47] The program was approved for use in Hawaiʻi, and in the mid-to-late 1960s it was employed in numerous Church units throughout the islands. George and Luana Hook were introduced to Project Temple in Kāneʻohe and attended the seminar for a few weeks before moving to the Kohala area on the Big Island. Shortly thereafter George became branch president and, wanting to help strengthen the members, introduced the program there. He recalled:

We interviewed many families . . . and got them ready for the seminar, and I taught it. Kohala is a plantation community. People don’t make much money there. . . . We had to raise money for the airfare, and we had to find lodging. .. . So in November 1968 . . . we had all of these families . . . with their children, go there [Hawaii Temple] to be sealed for time and all eternity, and had genealogy work prepared so that they can be sealed to their parents, to their ancestors, and everything. It was a great event.[48]

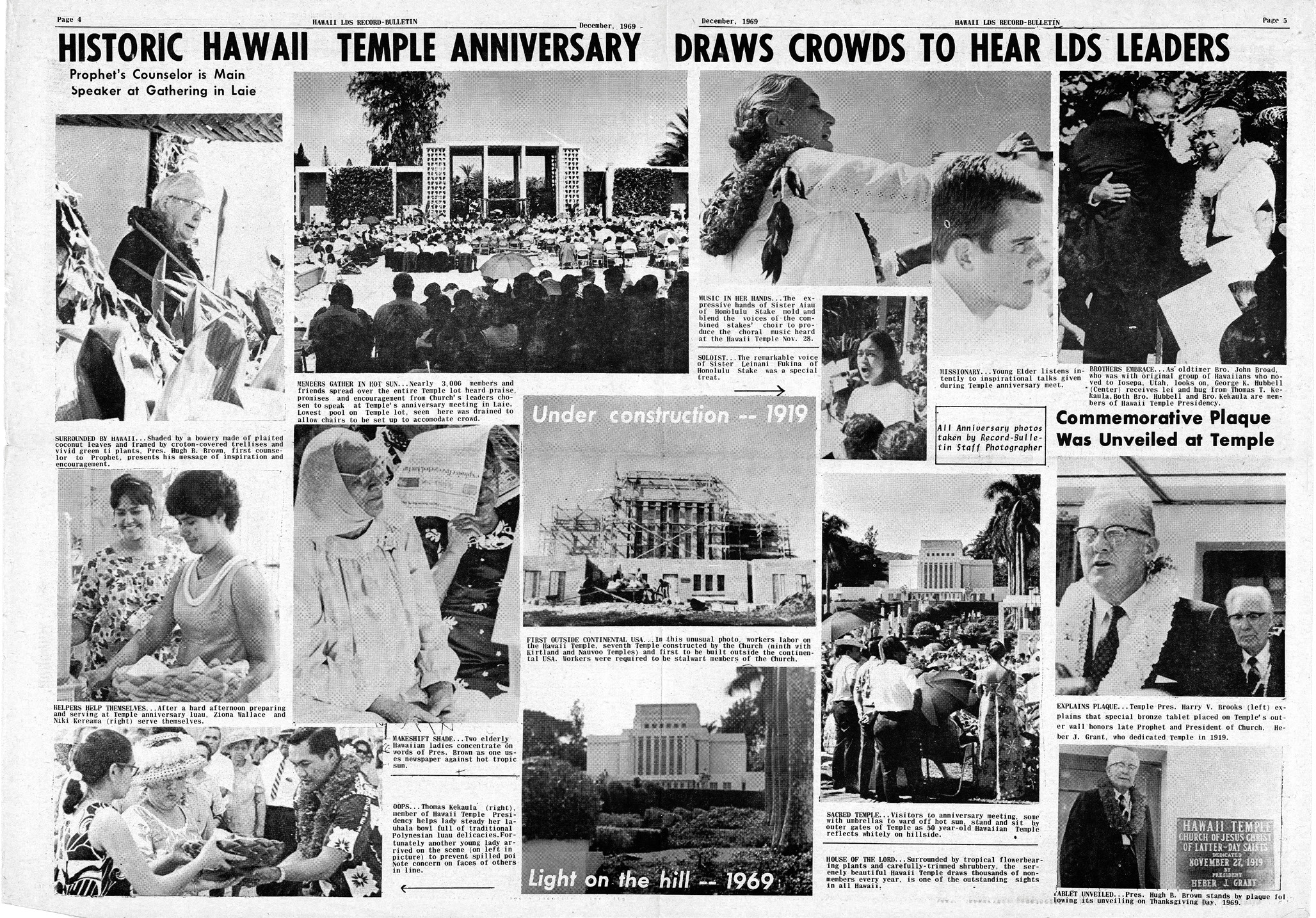

In celebration of the Hawaii Temple’s golden anniversary on Thanksgiving Day 1969, some 2,800 people gathered on the temple grounds to hear President Hugh B. Brown, First Counselor in the First Presidency, deliver the keynote address. Courtesy of BYU-Hawaii Archives.

In celebration of the Hawaii Temple’s golden anniversary on Thanksgiving Day 1969, some 2,800 people gathered on the temple grounds to hear President Hugh B. Brown, First Counselor in the First Presidency, deliver the keynote address. Courtesy of BYU-Hawaii Archives.

Project Temple was never adopted Churchwide and was replaced with another program in the years that followed, but its approved use in Hawaiʻi in the 1960s likely resulted in hundreds of previously married couples attending the Hawaii Temple and being sealed as families.

Golden Anniversary of the Temple

The temple’s golden anniversary in 1969 was a bright time for the Church in Hawaiʻi. The economic hardship of the 1920s and 1930s and the grim realities of World War II in the 1940s had given way to a buoyant outlook among the Hawaiian Saints in the 1950s and 1960s. Their widely expanded temple complex along with a new neighboring university and the Polynesian Cultural Center were reason enough for mounting optimism. Yet there were sure indications of spiritual progress as well—seen, for example, in the regular temple excursions from the outer islands and Japan and, perhaps most striking, in the fact that record years for temple work had increased to the point of beginning to appear almost normal.

The First Presidency approved the celebration of the temple’s golden anniversary on Thanksgiving Day, 27 November 1969, and sent President Hugh B. Brown, First Counselor in the First Presidency, to preside and deliver the keynote address. The celebratory day began early with traditional Thanksgiving Day temple sessions commencing every half hour from 5:30 to 7:00 a.m. Later that morning a special service was held in front of the visitors’ center. Speaking to an estimated twenty-eight hundred in attendance, President Brown encouraged the members to be found “in the line of duty and working diligently to bring forth the Lord’s gospel including vital temple work.” President Brooks noted that 1,274,986 ordinances had been performed in the temple since it was dedicated on 27 November 1919, then added, “The Saints in Hawaii are becoming more and more converted to temple work.”[49]

Notes

[1] The school began as a two-year junior college and a few years later was accredited as a four-year college, thus necessitating the addition of four more dorms and other facilities.

[2] See Alice C. Pack, The Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 1960–1963 (Lāʻie, HI: Church College of Hawaii, 1963), 94.

[3] See N. B. Lundwall, comp., Temples of the Most High (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1978), 152.

[4] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 94.

[5] See Yearly Temple Reports, 1961, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[6] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 98.

[7] Edward L. Clissold, journal, 18 May 1963, in the family’s possession.

[8] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 12–13. Numbers of missionaries from the Pacific: Hawaiʻi 46, Tonga 34, Samoa 24, New Zealand 18, Cook Islands 1.

[9] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 100. A temple report recorded: “A special meeting was held the night before where President Tietjen explained the endowment. It was translated to the Work Missionaries in their native tongue by Ralph D. Olson and Lafi Toelupe.” Yearly Temple Reports, 1960, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[10] Rufus Mahaere, oral history, 12 October 1984, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, OH-229, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives), 13–14.

[11] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 100.

[12] Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 101.

[13] The Church News reported: “Hawaii is fast becoming a center for world tourism and is literally the cross-roads of the Pacific. The Temple grounds tour spoken of as ‘a must’ for all tourists coming this way. . . . A total of 412,000 visitors called at the Hawaiian Temple Bureau of information and toured the Temple grounds during 1960 and 1961.” Church News, 28 April 1962, 6.

[14] Reuben D. Law, The Founding and Early Development of the Church College of Hawaii (St. George, UT: Dixie College Press, 1972), 119.

[15] Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011), 129. See Honolulu Advertiser, 25 January 1948, 8.

[16] Edward L. Clissold, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 11 June 1976, James Moyle History Program, MSSH 261, CHL, 20.

[17] Clissold, interview, 11 June 1976, 20.

[18] See Laura F. Willes, Miracle in the Pacific: The Polynesian Cultural Center (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 2012), 35–40. While hukilau had been staged in Lāʻie a few times in the late 1930s to raise funds for the Honolulu Tabernacle, it was not until after World War II that, in an effort to raise money for a new chapel in Lāʻie to replace the I Hemolele Chapel lost to fire years earlier, its real revenue potential was recognized.

[19] See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 165.

[20] See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 166; and Willes, Miracle in the Pacific, 42–43.

[21] For a more detail about the PCC, see Willes, Miracle in the Pacific.

[22] Hugh B. Brown, Polynesian Cultural Center Dedicatory Prayer, in Something Wonderful: Brigham Young University–Hawaii Foundational Speeches (Lāʻie, HI: Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2012), 35.

[23] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 132–33.

[24] “Architectural Beauty Sought in Changes of Hawaiian Temple,” Church News, 28 April 1962.

[25] See Gordon B. Hinckley, “Have Faith in God” (Brigham Young University–Hawaii devotional, 13 June 1986), in Excerpts from Talks from General Authorities Dealing with Church College of Hawaii / BYU–Hawaii, Church Education and Laie (booklet, BYU–Hawaii Archives), 23–24.

[26] See Pack, Building Missionaries in Hawaii, 132–33.

[27] Hugh B. Brown, “Dedicatory Prayer of the Hawaiian Temple Addition and the Bureau of Information,” 13 October 1963, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[28] See Willes, Miracle in the Pacific, 141–42.

[29] Clissold, journal, 10 March and 5 July 1964.

[30] See Willes, Miracle in the Pacific, 146–48; and Davis W. and Cynthia Eyre, “The Flop That Flipped,” Honolulu Magazine, October 1967, 27–28, 54–56.

[31] See R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018), 411–12.

[32] Quoted in Law, Church College of Hawaii, 69.

[33] See Alton L. Wade, “Laie—A Destiny Prophesied,” Ensign, July 1994, 68–70.

[34] Wade, “Laie—A Destiny Prophesied,” 70.

[35] Howard W. Hunter, 18 November 1994, Lāʻie, Hawaiʻi, C-633, President Shumway, box 1, Inauguration File, BYU–Hawaii Archives. See Vernice Wineera, “President Hunter Installs New BYU–Hawaii President,” Ensign, February 1995, 79.

[36] Yearly Temple Reports, 1960, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[37] Clissold, journal, 5, 6, and 14 May 1963.

[38] See Clissold, journal, 27 November 1964.

[39] Clissold, journal, 2 March 1965.

[40] Clissold, journal, 4 and 17 September 1965.

[41] “Personal Experiences of Edward L. Clissold, 1989–1984,” in family’s possession. See Alf Pratte, “Hawaii Temple Rededicated,” Ensign, August 1978, 77.

[42] Honolulu Advertiser, 19 November 1965, A-4.

[43] Charles Goo, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 18 March 2017, Lāʻie, Hawaiʻi, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 3–4.

[44] Hawaii Temple Bureau of Information Guide Book, preface, MSSH 058, box B, MS 58, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[45] Yearly Temple Reports, 1966, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, CR 335 7, CHL.

[46] Victor L. Brown, Second Counselor in the Presiding Bishopric, wrote: “‘Project Temple’ originated with the East Jordan Stake Committee for Aaronic Priesthood members over 21. Temporary permission was granted some stakes to use the program pending a new program. . . . J. Richard Anderson is a member of the East Jordan Stake and handles the distribution of the ‘Project Temple’ program. . . . [The program involves an] intensive 12 week course [later 14 weeks] from which members are expected to qualify themselves to advance to the Melchizedek Priesthood [and temple].” Victor L. Brown to LaVor L. Smith, 29 December 1965, General Files, Adult Aaronic Priesthood Department, CHL.

[47] James Richard Anderson, How to Use Project Temple: Handbook for Leaders (Salt Lake City: n.p., 1961?), CHL.

[48] George K. K. Hook, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 11 March 2017, Kailua, Kona, Hawaiʻi, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 3–4.

[49] Hawaii LDS Record-Bulletin 1, no. 3 (December 1969). See “Hawaii Temple Celebrates Golden 50th,” Ke Alakaʻi, 26 November 1969, 3.