A College and Rising Temple Success—1950s

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "A College and Rising Temple Success—1950s," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 255–280.

Aerial view of Lāʻie with newly constructed Church College of Hawaii campus at center (the temple is to the right and down). Later renamed Brigham Young University - Hawaii, the school formed a synergistic relationship with the temple that as continued ever since. Courtesy of BYU-Hawaii Archives.

Aerial view of Lāʻie with newly constructed Church College of Hawaii campus at center (the temple is to the right and down). Later renamed Brigham Young University - Hawaii, the school formed a synergistic relationship with the temple that as continued ever since. Courtesy of BYU-Hawaii Archives.

The 1950s began with a centennial celebration of the Church in Hawaiʻi. Similar to the Churchwide centennial twenty years earlier, an elaborate pageant was performed in Honolulu. As before, in the final scene the Church was represented by a replica of the Hawaii Temple, “which, being lighted, dominated the scene with ethereal beauty.”[1] The future was promising, yet perhaps no other milestone defines this era of the Hawaii Temple as well as the establishment of a Church university adjacent to the temple and the synergetic relationship that has followed.

During a visit to Hawaiʻi in 1921, Apostle David O. McKay envisioned Lāʻie as an educational center for the Saints in the Pacific and beyond. However, years of economic depression followed; then “the war came on and plans were laid aside.”[2] Starting in 1949, committees were periodically formed to consider such a school. At this time the largest concentration of Latter-day Saints lived in the Honolulu area, and Lāʻie was more than an hour’s drive away and only modestly sustained its roughly seven hundred residents, let alone hundreds of students needing boarding and part-time jobs. For these reasons, the committees studying the matter by and large concluded that the school should be located in or near the Honolulu area.

Lāʻie Master Plan

In 1951, during this period of recurring committee consideration of a school, David O. McKay became the ninth president and prophet of the Church. In that same year, former temple president Edward L. Clissold became the O‘ahu Stake president, and two years later he was given management of Zions Securities, which oversaw nearly all the Church-owned property in Lāʻie. In a June 1953 meeting with President McKay, Clissold requested permission to have a “master plan” drawn to control the expansion and development of Lāʻie.[3] The request was granted. Clissold recalled: “President McKay said he’d like to stand on the steps of the temple and see the ocean. At that time the road ran down two blocks and then turned off [to Puʻuahi Street] and went down the highway.”[4] Harold W. Burton, who had designed the temple, drew up the community master plan, which included President McKay’s request of a direct road and view from the temple to the ocean. The plan was approved by the First Presidency in May 1954.[5]

Church College of Hawaii (Brigham Young University–Hawaii)

In December 1954 a committee unanimously chose to locate the college campus southeast of the temple (in background). From right: Joseph Wilson, superintendent of construction; George Lake, chief foreman, and wife Magdeline; and Reuben D. Law, college president. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In December 1954 a committee unanimously chose to locate the college campus southeast of the temple (in background). From right: Joseph Wilson, superintendent of construction; George Lake, chief foreman, and wife Magdeline; and Reuben D. Law, college president. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Two months after approving the Lāʻie master plan design, the First Presidency issued a news release that the Church would build a new college in Hawaiʻi and projected the college would open in the fall of 1955. Within a week Dr. Reuben D. Law (who would become the school’s first president) and a newly formed committee began conducting another survey,[6] and like previous committees they recommended the college be located near Honolulu. Yet in early November 1954, President McKay made it clear that the college would be built in Lāʻie.[7]

The name decided on was the Church College of Hawaii[8] (renamed Brigham Young University–Hawaii in 1974), and Harold Burton, who had now designed both the temple and the town, would design its college as well.[9] Various sites in Lāʻie were considered for the school, and on 8 December 1954 the committee unanimously chose its present location southeast of the temple.[10] Just two months after choosing the site, President McKay personally presided over the school’s groundbreaking and dedication ceremonies on 12 February 1955.[11] Among President McKay’s comments to those gathered, he admonished the residents of Lāʻie:

Keep your yards beautiful. Keep your streets clean and make it an attractive village, the best in the Hawaiian Islands. Why shouldn’t it be, in the shadow of that House of God, standing out in beautiful white in the daytime and an illuminated building at night. But above all, may the beauty of your town be a symbol of the beauty of your characters. This must be a moral town [where] you may love and live in peace so that people who enter this village will feel that there is something different here from any other town they have ever visited.[12]

Then, in a spirit of prophecy, President McKay declared, “You mark that word, and from this school, I’ll tell you, will go men and women whose influence will be felt for good towards the establishment of peace internationally.”[13] And in the dedicatory prayer, he boldly declared “that this college, and the temple, and the town of Laie may become a missionary factor, influencing not thousands, not tens of thousands, but millions of people who will come seeking to know what this town and its significance are.”[14]

Groundbreaking and dedication of the college grounds. Left to right: D. Arthur Haycock, president of the Hawaii Mission; Edward L. Clissold (with shovel), president of the Oʻahu Stake and college board chairman; Bishop James Uale, Lāʻie; President David O. McKay; George Kekauoha, counselor in the Oʻahu Stake presidency; Reuben D. Law, college president; Ralph E. Woolley, former temple and Oʻahu Stake president; Benjamin L. Bowring, president of the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Groundbreaking and dedication of the college grounds. Left to right: D. Arthur Haycock, president of the Hawaii Mission; Edward L. Clissold (with shovel), president of the Oʻahu Stake and college board chairman; Bishop James Uale, Lāʻie; President David O. McKay; George Kekauoha, counselor in the Oʻahu Stake presidency; Reuben D. Law, college president; Ralph E. Woolley, former temple and Oʻahu Stake president; Benjamin L. Bowring, president of the Hawaii Temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

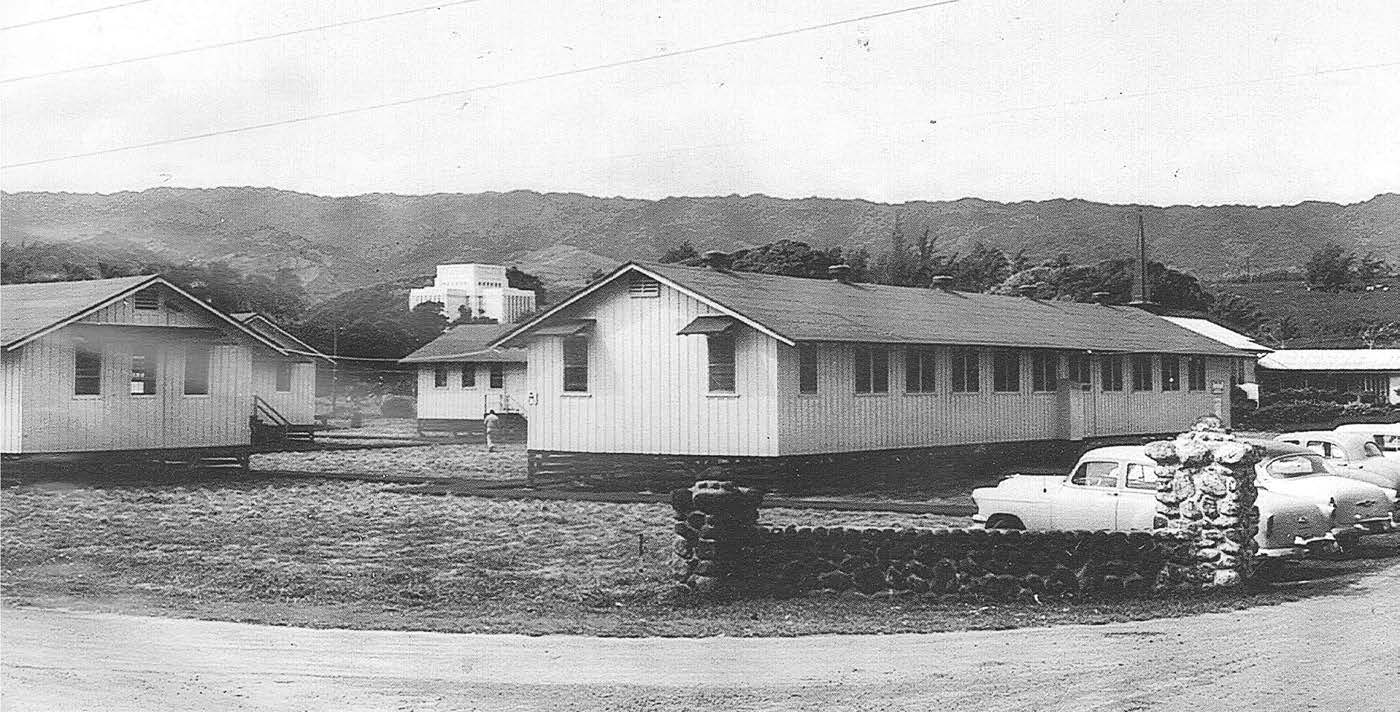

By transferring in several war surplus buildings—and using the existing Lāʻie Chapel, nearby social hall, and the old mission home (Lanihuli) as the girls’ dorm—a temporary campus came to life down the northeast slope of the temple (the very location where David O. McKay had envisioned a school thirty-four years earlier during the flag-raising ceremony at the mission school). True to President McKay’s request, the school opened its doors in these temporary facilities in September 1955 with 153 students and 20 faculty and administrators.[15] These provisional facilities were used until the first phase of the permanent campus could be built in the dedicated location.

Early on, the Church College of Hawaii connected with the temple. College president Reuben Law felt the temple had an important role to play in meeting the lofty vision President McKay set forth for the school. Preceding the school’s opening, the college president and staff held a special testimony meeting and session in the temple with the O‘ahu Stake leadership and the temple presidency. President Law wrote, “This was a highly spiritual occasion long to be remembered, followed by many sessions in the temple during years in Hawaii.”[16] During the crowded days just before the school’s opening, President Law and temple president Benjamin L. Bowring arranged a special temple session “for faculty and staff of The Church College of Hawaii and their partners.” President Law recorded, “An inspiring testimony meeting was held [in the temple chapel] at which many heart-warming testimonies were borne followed by the choice experience of going through the temple together.”[17] Then, ending the first year as they began, “during the evening of commencement a special session in the Hawaiian Temple was attended by the college faculty and their husbands or wives.”[18]

With the addition of several war-surplus buildings and use of the Lāʻie Chapel and other nearby buildings, a temporary college campus (1955–58) came to life near the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

With the addition of several war-surplus buildings and use of the Lāʻie Chapel and other nearby buildings, a temporary college campus (1955–58) came to life near the temple. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Continuing to foster this tradition, Wendell B. Mendenhall, chairman of the Pacific Board of Education, wrote in a letter to Dr. Richard T. Wootten, second president of the Church College of Hawaii, that in an effort to “maintain a very high spiritual plane among our teaching staff at this Church school . . . we invite you to have the teachers at the Church College of Hawaii visit the temple regularly and particularly do so as a college staff at an appointed time.”[19]

This practice of the college employees attending temple sessions together continued for several years, and throughout the college’s history, member employees have agreed as a condition of employment to maintain a standard of personal conduct consistent with the standards required for temple privileges.

Temple Renovation

First faculty of the Church College of Hawaii. College president Reuben Law (front row center) felt the temple had an important role to play in meeting the lofty vision President David O. McKay set forth for the school. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

First faculty of the Church College of Hawaii. College president Reuben Law (front row center) felt the temple had an important role to play in meeting the lofty vision President David O. McKay set forth for the school. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The latter half of the 1950s was a dynamic time in Lāʻie. As the new school with its growing number of students and employees proceeded in its temporary location, the permanent college campus was being constructed by a multitude of so-called building missionaries (also called labor missionaries). These workers were also part of the renovation work on the temple, and all this occurred as the town’s master plan was being implemented.

The building missionary program was first implemented in Tonga as a means of constructing Liahona High School, and the program was later used in Samoa and New Zealand. As plans for the permanent college campus in Lāʻie took shape, President McKay asked Wendell B. Mendenhall, chairman of the Church Building Committee, to use building missionaries to construct the Church College of Hawaii as well.[20] Directed by Joseph E. Wilson, the construction of the main campus was finished in 1958. During this time, more than fifty mainland couples (some with young families) and approximately 150 men from Hawaiʻi had answered the call to labor on the Church College of Hawaii.[21] A book of remembrance published upon completion of this project notes: “The temple has been a source of inspiration and strength to the Labor Missionaries, and they feel that their connection with it has been a special blessing to them. All have been faithful in attending regular sessions as their work has permitted, as well as the once-a-month session for the Labor Missionaries only. Many have accepted guiding responsibilities and duty at the counter in the Bureau of Information. Some have officiated.”[22]

Labor missionaries constructed the permanent campus of the Church College of Hawaii between 1955 and 1958. During their service they contributed more than nineteen thousand hours of renovation work on the temple and the Bureau of Information. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Labor missionaries constructed the permanent campus of the Church College of Hawaii between 1955 and 1958. During their service they contributed more than nineteen thousand hours of renovation work on the temple and the Bureau of Information. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

During their service these missionaries collectively contributed more than nineteen thousand hours of renovation work on the temple and the Bureau of Information. Providing some detail of this renovation, the temple president reported:

All outside areas were sand blasted, a water proof coating applied, the roof replaced, and a new soft shade of green was applied to the outside of the Temple, the Information Bureau, the tiered pools, the fern houses and the statuary. All interior wall space in the Temple with the exception of the murals were beautifully decorated. With the addition of new drapes and new carpet, the interior is beautifully done. The Bureau was also painted on the inside. Lighting of the new parking area added much. The installation of an air conditioning unit in the Temple also adds much to the comfort of the people.[23]

Labor missionaries circa 1957. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Labor missionaries circa 1957. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

That “a new soft shade of green” was applied to the temple, Visitors’ Bureau, and pools may seem unusual to some who have only known the temple to be brilliant white in appearance. Apparently it was peculiar to people at that time as well. Historian Joseph H. Spurrier observed: “The temple was given a new coat of paint—a pale green. Originally white, the new shade was intended to blend better with the landscaping. The effect, however, was shock for most who saw it. Eventually, however, the green faded to an even paler shade and in a year or two the glistening white, to which most are accustomed, was restored.”[24]

New Road Arrangements in Lāʻie

In 1955 there were only two entrances from Kamehameha Highway into the town of Lāʻie: Lanihuli Street and Puʻuahi Street (which President Waddoups had circuitously connected to the temple in the early 1930s). At the time, Puʻuahi Street was more or less the southern edge of the village houses. However, the master plan, which would incorporate President McKay’s wish to view the ocean directly from the temple and now included the new college campus, would bring sweeping change to the temple town. Amid this makeover, and in his role as manager of Zions Securities Corporation, President Clissold in 1957 reported:

Laie today has many scars and will have a few more before the road pattern is complete. When it is finished, we shall have one of the beauty spots of Hawaii, if not of the world. With the Temple at the top of one broad avenue and the college at the end of another, and with all the intervening roads surfaced and landscaped, and with homes properly maintained and yards beautified, we shall have a community which will be a credit to the Temple and the college and a home land of which we can all be proud.[25]

Most dramatic of these community changes for the temple was construction of the double-lane road extending directly east from the temple to Kamehameha Highway and clearing the beachfront of any obstruction on the other side. This provided not only the unobscured view from the temple to the ocean that President McKay desired but also, with its landscaping, a striking, almost framed view of the temple from the highway.

In response to President David O. McKay’s wish for an unobscured view from the temple to the ocean, a double-lane road extending directly east from the temple to Kamehameha Highway and the beachfront was cleared of any obstruction. The new road was named Hale Laʻa, meaning “holy temple” in Hawaiian. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

In response to President David O. McKay’s wish for an unobscured view from the temple to the ocean, a double-lane road extending directly east from the temple to Kamehameha Highway and the beachfront was cleared of any obstruction. The new road was named Hale Laʻa, meaning “holy temple” in Hawaiian. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

With completion of the master plan, the new streets were named and some of the older streets were renamed. Using Mary Kawena Pukui’s Hawaiian language book, in 1961 art professor Wylie Swapp, one of the original faculty members at the Church College of Hawaii, submitted a number of street names to the community association (Hui Lau Lima) for consideration. Of wanting to name the street extending from the temple to the ocean Hale Laʻa, meaning “holy temple” in Hawaiian, Swapp recalled: “It seemed like some people objected to Hale Laʻa (‘holy temple’) as being not reverent enough, that it shouldn’t be used on a street name but, I think, [Edward] Clissold was the one who finally said it would be appropriate. He was the head of Zions Securities, and he was president of the temple, and he was president of the [LDS] stake, so it worked out.”[26]

Of the street running north–south directly in front of the temple, Swapp explains: “I thought . . . that Puʻuhonua [place or city of refuge] would be a good name for the street that kind of encloses Laie. . . . But that was used someplace else.” Swapp then recommended its current name, Naniloa (“extensive beauty”) Loop. And the significantly expanded Iosepa Street, named years earlier after the Polynesian colony in Skull Valley, Utah, whose members returned to Lāʻie when the temple was built, respectfully retained its name. As for the street leading directly to the new college campus from Hale Laʻa, community members had already begun using the name Kulanui, a compound word made up of two shorter Hawaiian words, kula meaning “school” and nui meaning “important or large.”[27] Of the two most prominent streets born of this master plan, John S. Tanner, the school’s tenth president, said:

This university was intentionally erected in the shadow of a temple—the only Church college to be so located from its inception. Those who built the Church College linked the temple and school spatially by laying out two new intersecting streets: the streets of Hale Laʻa (Hawaiian for holy house) and Kulanui (Hawaiian for big school). May these houses of learning and of light also remain linked spiritually.[28]

Of the union of the two main roads added in the 1950s—Hale Laʻa extending from the temple (upper left) and Kulanui extending from the college—school president John S. Tanner said, “May these houses of learning and of light also remain linked spiritually.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Of the union of the two main roads added in the 1950s—Hale Laʻa extending from the temple (upper left) and Kulanui extending from the college—school president John S. Tanner said, “May these houses of learning and of light also remain linked spiritually.” Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Now in direct view of the temple and once again owned by the Church, the beach (aptly named “Temple Beach”) became an even more popular location for local baptisms. Over the years thousands have been baptized with the temple as a backdrop. During those years a tradition began of seating the newly baptized member in a chair facing the temple for confirmation, with the beauty of the temple in full view, emphasizing to the newly baptized and confirmed member the goal to someday enter its doors and make further covenants and receive greater blessings.[29] Barbara Clarke (temple matron from 1998 to 2001) added, “It had such meaning for a child to be baptized, then look to the temple on the hill at the other end of the boulevard, being taught that the temple was their next important step.”[30]

College and Temple: A Higher Education

From the beginning, the school and temple formed a synergistic relationship that has continued ever since. For example, almost immediately following completion of the permanent campus, the empty dorms in summer began to be used by outer-island groups coming to do temple work,[31] and couples that met at the college began to marry in the temple.[32] Yet perhaps the greatest cumulative benefit has been the expanded perspective the temple has added to the students’ college experience and what they have given to the temple as they have served therein. “I’m convinced that you . . . will become the leaders you need to become,” said BYU–Hawaii president John S. Tanner, “not just from the lessons you learn here but lessons you will learn in the Temple. . . . Go to the Temple often.”[33]

Interestingly, dedication of the college’s permanent campus in 1958 coincided with the dedication of the New Zealand Temple. Another temple in the Pacific was a wonderful sign of progress, yet also the beginning of the Laie Hawaii Temple’s decline in geographic reach. New Zealand was now the closest temple for much of the Pacific and Southeast Asia. However, the school in Lāʻie has continued to draw students from all parts of the Pacific and Asia, and during their years attending this college many of them have regularly attended, served as workers in, and developed a love for the temple and its blessings. This combined education—college and temple—has contributed to the fulfillment of President McKay’s vision that from this school would go “men and women whose influence will be felt for good towards the establishment of peace internationally,” and in this way the Laie Hawaii Temple has continued its incredible international reach. As David W. Cummings presciently described not long after the school’s construction, “On a hill in Laie rise the white walls of a temple. And from the terrace at its front door, you can see . . . the Church College of Hawaii. School and Temple, fusing the influence of education with the ultimate in spiritual enlightenment—this dual force sets far horizons for the good that will come out of Laie.”[34]

Changes in Temple Presidencies

Beyond the new college, temple renovations, and community master plan, several other noteworthy developments affecting the temple occurred in the 1950s. After more than nine years as temple president and matron, Ralph and Romania Woolley were released in 1953, and Benjamin and Leone Bowring, accompanied by their teenage son John, took their place. Overseeing the temple when the college was announced in July 1954, President Bowring was asked to be part of the survey team and to serve on the college’s first board of directors. During their service the Bowrings added a number of sessions to the temple’s weekly schedule, resulting in a significant increase in the work. In addition, on 18 December 1954 President Bowring presided over a special evening devotional on the temple grounds at which recently installed floodlights were officially turned on for the first time to illuminate the temple at night. It was remarked, “The temple, world famous for its beauty by day, was now even more beautiful by night.”[35]

Unexpectedly, on 28 November 1955 President David O. McKay announced in a press conference that Benjamin and Leone Bowring would serve as the first president and matron of the nearly completed Los Angeles California Temple.[36] This new calling required the Bowrings to depart Hawaiʻi within a week. Under directive of the First Presidency, Edward Clissold (then O‘ahu Stake president) arranged for the counselors in the temple presidency, LeRoy Ohsiek and Wallace G. Forsythe, to continue the ordinance work until a new temple president could be appointed.[37]

Coinciding with this transition in temple leadership, the First Presidency issued a letter regarding the accumulation of “a large number of male names for which endowment work has not been done.” It was thus requested that each temple in the Church conduct two endowment sessions for brethren each Saturday and that assignments be coordinated through priesthood quorums to fill these sessions. The first of these special sessions was to be held on Saturday, 14 January 1956, with others to follow weekly until the necessary work was accomplished.[38] Years earlier, President Ralph Woolley had established a session on Saturday to accommodate more priesthood brethren; thus this new First Presidency directive formalized and extended those efforts. The practice of priesthood temple sessions, in some form and with some consistency, would continue in the Hawaii Temple for years to come.

Ray and Mildred Dillman were set apart as president and matron of the Laie Hawaii Temple on 13 January 1956 and arrived in Hawaiʻi in February. President Dillman was a former member of the Utah State Board of Education, the Board of Trustees of Utah State University, and the Utah Junior College Board, and during his calling as temple president he served on the new Church College of Hawaii Board as well.[39] In the midst of a community managing a new college, constructing a permanent campus, and rearranging its entire outlay to fit a master plan, “ordinance work,” President Dillman reported, “was the highest in the history of the Temple. . . . It is gratifying to see the increases in marriages, and living sealings.”[40]

The Temple Grounds: “This Is the Lord’s Work”

In October 1956 a Honolulu newspaper reported, “Sometimes called the Taj Mahal of the Pacific because of its beauty, the Mormon Temple last year attracted 157,000 visitors—making it possibly Hawaii’s biggest single tourist attraction away from Waikiki.”[41] President Dillman reported that on an average day in 1957, representatives from thirty-three states or nations visited the temple grounds. In that same year sixty-four thousand people received a message from guides, fifty thousand pamphlets were distributed, and fourteen hundred copies of the Book of Mormon were sold. “Visitors,” he added, “express sincere praise for the beauty of the grounds and for the courteous treatment of the guides.”[42]

Remarkable aesthetic beauty of the temple grounds has been achieved over the years by those who, often without notice, maintain them. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Remarkable aesthetic beauty of the temple grounds has been achieved over the years by those who, often without notice, maintain them. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Credit for this aesthetic success must in good measure be given to those who maintain the outward beauty of the temple and its grounds. This obviously requires copious work, talent, and care and reflects tribute on those who labor, generally in anonymity, to do so. Samuel Hurst, a Visitors’ Bureau missionary in the 1950s, recounted that one day when a group of visitors were complimenting the beautiful architecture and grounds of the temple, Joe Chang, superintendent of the grounds, entered the bureau barefoot and dressed in a faded shirt and jeans that were torn off below the knees. Hesitant at first, thinking Chang might not want attention in his condition of dress, Elder Hurst determined to introduce him anyway as the person responsible for the temple grounds. The visitors expressed their praise to him personally, emphasizing their feeling that this was one of the beauty spots of the world. Chang was silent, and Elder Hurst thought maybe he did not know what to say. However, when the visitors had gone, Chang said, “Elder Hurst, please do not do that again for it is very embarrassing. For you know this is the Lord’s house and grounds. He is the one who is doing this, not us.”

“Embarrassing,” replied Elder Hurst, “to have so many complimentary things said about you and your work? You should be pleased with these compliments.”

“But Elder Hurst,” Chang responded, “we cannot put color into these plants and flowers. All we can do is to try to keep them watered and cultivated.”

Elder Hurst tried his line of argument again, but Chang replied, “This is the Lord’s work. It is He who gives this place its beauty for we cannot do it. If you think we can, just look at our homes. They do not look like this place.”[43]

1957 Tidal Wave Threat

A deadly tsunami had struck Hawaiʻi in 1946. When a warning siren sounded a decade later on Saturday, 9 March 1957, those in the temple prayed for protection. No lives were lost. Photo of the wave surging over the beach directly east of the temple courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

A deadly tsunami had struck Hawaiʻi in 1946. When a warning siren sounded a decade later on Saturday, 9 March 1957, those in the temple prayed for protection. No lives were lost. Photo of the wave surging over the beach directly east of the temple courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

A string of volcanic and seismic activity around the edges of the Pacific Ocean (the “Ring of Fire”) places Hawaiʻi at risk of tidal waves (tsunamis). A deadly tsunami had struck Hawaiʻi in 1946, and when the warning siren sounded on Saturday, 9 March 1957, residents were anxious. “A Priesthood Session was being held,” recalled temple matron Mildred Dillman, and “one of the Labor Missionaries had a small transistor radio outside of the Temple and many of the Saints had gathered around the Temple because it was on higher ground.”[44]

Reuben Law, present in the session, explained that President Ray Dillman interrupted the session with the tense news and called on Jay A. Quealy, a member of the Honolulu Stake, “to offer a special prayer, supplicating the Lord to avert and lessen the danger from the tidal wave and to protect the lives of the people. All present exercised their faith in connection with this prayer. Although some of us felt grave concern for the safety of our loved ones, the temple session then continued as usual.”[45] The waves were much smaller than expected, residents heeded the warning to get to higher ground (a large number gathering at the temple), and no lives were lost.

Sister Dillman recorded: “President Dillman said to one of the natives that was in the Session, ‘We have just witnessed a miracle, much like Moses and the Red Sea.’ He was answered, ‘What miracle? This was only the Lord answering the prayer of His Priesthood. . . . We were doing His work and He never forgets to answer.’”[46] The temple remains a tsunami evacuation site for Lāʻie residents, and yearly the elementary schoolchildren walk up the street to “Temple Hill” as part of their tsunami drill.

Temple Ordinances Translated into Māori and Samoan

The New Zealand Temple (announced 1955, dedicated 1958) was designed specifically to use an audiovisual system in its depiction of the endowment.[47] Such a system facilitates the presentation of the endowment in other languages, and it was determined that translation of the temple ordinances into Māori and Samoan for use in that temple would be done in the Hawaii Temple. The 20 October 1957 Lāʻie community newspaper noted, “Great honor has come to Stewart Meha of New Zealand, Feagaimalii Galeai of Laie, Tau Tua Tanoai, also of Laie. By special assignment from President David O. McKay, these men are engaged in important translation work in preparation for ordinance work in the Maori and Samoan languages in the New Zealand Temple which will open in the spring of next year.”[48]

Although the number of Samoan- and Māori-speaking Saints had increased in Hawaiʻi, these translations would not be used in the Hawaii Temple until 1964, when an audio system was installed. However, in 1962 President Bowring received permission to begin using the Samoan translation in the Los Angeles Temple, which was audio-capable. More than forty-five Samoans attended the inaugural session on 21 March 1962, several of whom had never heard the ceremony in their native tongue.[49] A Church News article explained:

Among them was a former Samoan chief, Savea Aupiu, over 90 years of age. During two years that President Bowring presided over the Hawaiian Temple, Chief Aupiu, who had come from his native Samoa to do temple work [in Hawaii], never missed a session though he could not understand a word of English. He has now lived about six months in the Los Angeles area and attended the temple regularly two or three times a month. His joy was complete last March 21 when he could hear the full temple ceremony in his own tongue.[50]

The dedication of the New Zealand Temple in April 1958 brought an end to a remarkable streak of group excursions by Māori Saints to the Hawaii Temple. As mentioned, with the exception of the years surrounding World War II, these fifteen-thousand-mile round-trip journeys had occurred every couple of years for nearly four decades.

Tahitian Saints Heed Prophet, Avoid Disaster

Despite being closer in proximity to the New Zealand Temple, in 1959 a group of about thirty Tahitian Saints arranged to travel aboard the Paraita (the mission yacht) to the Hawaii Temple. Church leaders had given approval for the voyage, so the members were surprised when former mission president Ernest Rossiter delivered a special message from President David O. McKay that the trip should not be made. Though very disappointed, the Saints accepted the counsel from their prophet. Kathleen C. Perrin explains, “A few days later, when they would have been at sea, the ship’s captain received an urgent message from the harbormaster. The Paraita was sinking in the harbor. An undetected rotting pipe had burst, and the Saints would have been three hundred miles from land if they had left as scheduled. Furthermore, it was discovered that the gears in the transmission were completely worn out and could never have made the trip to Hawai’i and back. The faith of the Tahitian Saints was strengthened knowing that a prophet of the Lord had been inspired regarding their welfare.”[51]

Fortieth Anniversary and Statehood

The year 1959 saw a flurry of matters related to the Hawaii Temple. A renovation of the temple grounds conducted that spring included the needed repair or replacement of sidewalks and steps as well as the outdoor plumbing and sprinkling system, and fountains were added to the pool in front of the Visitors’ Bureau.[52] In November a celebratory program was held on the renovated temple grounds to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the temple’s dedication. Special speakers included Olivia Waddoups, the first temple matron (President William M. Waddoups had passed away three years earlier), and former temple matron Romania Woolley, wife of temple builder President Ralph E. Woolley (who had passed away two years before).[53] Then, less than two weeks after commemorating the anniversary, the Dillmans were notified of their release as temple president and matron, and H. Roland Tietjen and his wife Genevieve, who were at that time directing the temple Visitors’ Bureau, were called to replace them.[54]

Yet perhaps the most consequential event for the temple that year was Hawaiʻi’s statehood. A US territory since 1898, Hawaiʻi became the fiftieth state in 1959. This brought change to Hawaiʻi, mainly in the form of large increases in tourism and unprecedented economic growth. Contributing to this growth, several mainland-based corporations and small businesses began to establish offices in Hawaiʻi, and among those men and women who came were Church members.[55] As will be seen in the years that followed, this surge of visitors and arrival of Church members would be among the contributing factors in the largest structural expansion of the Hawaii Temple and Visitors’ Bureau since they were built.

Steady Temple Service

The 1950s brought astonishing change to Lāʻie—the advent of the Church College of Hawaii, the implementation of a community master plan, renovations to the temple, leadership changes, statehood, and record numbers of visitors to the temple grounds and of ordinances performed in the temple. Yet as it had been since its dedication, the temple’s lifeblood remained the consistent yet generally unheralded service of its workers and patrons. Group excursions from the outer islands continued, often at immense sacrifice. To raise the money needed to attend the temple with her fellow Maui Saints, Linnel Taniguchi recalls rising early in the morning to pick kiawe tree beans to sell for a penny a pound to the local dairy and ranchers as fodder for their animals. In addition, she would wash the clothes of Filipino sugarcane workers for two dollars a month. “Whatever money they gave me I put the money in the jar so that we had enough money to go to the temple.”[56]

And like so many other Oʻahu Saints, Solomon and Lillian Kaonohi made regular temple attendance part of their lives. Every Wednesday, Solomon would close his medical practice in Honolulu at noon in order to pick up extended family along the way to his home in Waimānalo, where his wife would join them as they continued the considerable drive to the temple. Their daughter Kanani recalled: “I remember watching my mom ironing long white pieces of material and folding it ever so gently and placing it in a bamboo suitcase. Then she would prepare a delicious meal, usually shoyu chicken and rice which was our favorite, and leave it on the stove for us children to have for dinner. My dad would arrive home early in the afternoon with my kupuna [grandparents] and aunties to pick up my mom and off they would go to the temple. . . . They would come home ever so late in the evening because they would repeat that long drive back to Kapahulu to drop off my kupuna and aunties before coming home to Waimanalo.”[57]

Notes

[1] Clarice B. Taylor, “Mormon Pageant Applauded; Will Be Repeated Tonight,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 6 August 1950, 6.

[2] Edward L. Clissold, quoted in Reuben D. Law, The Founding and Early Development of the Church College of Hawaii (St. George, UT: Dixie College Press, 1972), 37. See Edward L. Clissold, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 11 June 1976, James Moyle History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), 18–19.

[3] Clissold, quoted in Law, Church College of Hawaii, 39.

[4] Edward L. Clissold, interview, 11 February 1980 and 5 April 1982, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection, OH-103, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives), 49.

[5] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 39.

[6] See “Big Outlay Slated For Mormon Junior College,” Honolulu Advertiser, 28 July 1954.

[7] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 46. After the report was submitted, President McKay asked Clissold what he thought of the school’s location near Honolulu. Clissold responded, “President McKay, I can’t forget Laie.” Clissold then recorded, “He slapped my knee—I think I still have the mark on it—and said, ‘Good. . . . Now we have their report, we appreciate it, but the school will be at Laie’” (Clissold, interview, 11 February 1980 and 5 April 1982, 19). Of this experience with President McKay, Clissold later stated, “I cannot tell you how thrilled I was . . . to find that [President McKay’s] mind was fixed on this land [Laie] which has been dedicated to the gathering of our people. The resources of Laie have been dedicated to education, to spiritual betterment and better life and living for our people” (Law, Church College of Hawaii, 60–61). John S. Tanner, tenth president of BYU–Hawaii, said: “I’m convinced that David O. McKay established the university here [in Laie] to be in the shadow of the temple. It’s the reason that so many people came here and that this continued to be a Zion place, a place of refuge and of gathering. . . . We [BYU–Hawaii and the Polynesian Cultural Center] are extensions of the Temple” (John S. Tanner, devotional given at Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 29 November 2016).

[8] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 48.

[9] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 50.

[10] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 52.

[11] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 60.

[12] David O. McKay, Groundbreaking Services, 12 February 1955, Church College of Hawaii, as quoted in Law, Church College of Hawaii, 68.

[13] McKay, Groundbreaking Services, 68.

[14] McKay, Groundbreaking Services, 68.

[15] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 92. See also R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018), 332.

[16] Quoted in Law, Church College of Hawaii, 81.

[17] Quoted in Law, Church College of Hawaii, 89.

[18] Quoted in Law, Church College of Hawaii, 124.

[19] Wendell B. Mendenhall to Richard T. Wootten, 30 June 1958, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[20] See David W. Cummings, Mighty Missionary of the Pacific: The Building of the Program of the Church (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1961); and Britsch, Moramona, 332–33.

[21] See ʻO Ka Nani O Ke Akua Ka Naʻauao, Church College of Hawaii and Its Builders (Lāʻie, HI: self-published, 1958), BYU–Hawaii Archives, [44, 62]; page numbers supplied from the digital archive at https://

[22] Naʻauao, Church College of Hawaii and Its Builders, [62].

[23] “President Dillman Presents Progress Report,” Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957, BYU–Hawaii Archives. See Naʻauao, Church College of Hawaii and Its Builders. For its first thirty-eight years, the Hawaii Temple functioned without air-conditioning—relying instead on open windows and trade winds flowing from the northeast.

[24] Joseph H. Spurrier, “The Hawaii Temple: A Special Place in a Special Land,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 7, no. 1 (1986): 33.

[25] Edward L. Clissold, “In Appreciation,” Hui Lau Lima News, 3 March 1957, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[26] Quoted in Mike Foley, “Origins of Laie Street Names,” Nanilaie.info, http://

[27] See Foley, “Origins of Laie Street Names.”

[28] John S. Tanner, “I See a School,” Inauguration of Dr. John S. Tanner, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 10 November 2015.

[29] Riley M. Moffat, longtime Lāʻie resident and bishop, explained this tradition to the authors.

[30] Barbara J. R. Clarke, reminiscence, CHL, 111.

[31] Ray E. Dillman, Hawaii Temple Quarterly Report, 31 December 1957, Hawaii Temple Subject Files, CHL.

[32] See Law, Church College of Hawaii, 162, 183; and “‘Talk story’ with Keawe Enos,” Kaelo o Koʻolauloa, 11 February 2005.

[33] John S. Tanner, “Thoughts on Thanksgiving and Christmas,” Brigham Young University–Hawaii devotional, 29 November 2016, https://

[34] Cummings, Mighty Missionary of the Pacific, 256.

[35] Spurrier, “Hawaii Temple,” 33. For another account, see Law, Church College of Hawaii, 55.

[36] See Honolulu Star Bulletin, “Laie Temple Chief Will Take Over Los Angeles Post,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, 28 November 1955, 14; “Benjamin L. Bowring Named President, Elder Steed Chosen,” Church News, 3 December 1955, 2; and “President Bowring Begins Work at L. A. Temple,” Church News, 31 December 1955, 5.

[37] See Hawaiian Temple Report, 12 December 1955, Hawaiian Temple Subject Files CR 335, CHL, 25.

[38] In letter from David O. McKay, Stephen L Richards, and J. Reuben Clark, to stake presidents, 15 December 1955, transcribed in The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846–2000: A Documentary History, ed. Devery S. Anderson (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), 301.

[39] See Richard T. Wootten to Mildred M. Dillman, 29 June 1962, UAH-002, box 12:1, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[40] Ray E. Dillman, Hui Lau Lima News, 22 December 1957, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 1.

[41] “Laie’s Mormon Temple Gets a New Dress,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, 6 October 1956, 3.

[42] “President Dillman Presents Progress Report,” Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957.

[43] Samuel H. Hurst, autobiography, MS 2401, CHL, 34–35.

[44] Mildred M. Dillman, “The Lord Listens to His Priesthood,” in the authors’ possession.

[45] Law, Church College of Hawaii, 143.

[46] Dillman, “The Lord Listens to His Priesthood.”

[47] See James B. Allen, “Technology and the Church: A Steady Revolution,” 2007 Deseret Morning News Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret Morning News, 2006), 147. “Beginning with the Swiss Temple [dedicated 1955], the endowment has been presented through the use of tape recordings and motion pictures. The presentation is thus not only more efficient and effective but also more adaptable to different languages.”

[48] “Men Honored by Special Temple Assignments,” Hui Lau Lima News, 20 October 1957, 5.

[49] See Henry A. Smith, “Another Language Story,” Church News, 7 April 1962, 5.

[50] Smith, “Another Language Story,” 5.

[51] Kathleen C. Perrin, “Seasons of Faith: An Overview of the History of the Church in French Polynesia,” in Pioneers in the Pacific, ed. Grant Underwood (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 201–18. Perrin continues, “Finally four years later a group of Saints was able to travel to the recently completed New Zealand Temple, where the first temple session in the Tahitian language was conducted on December 20, 1963.”

[52] See “Temple Schedule,” Hui Lau Lima News, 19 April 1959, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 4.

[53] See Wallace G. Forsythe, Laie Hawaii Temple annual historical reports, 1959, CR 335 7, CHL.

[54] See “President Dillman Released,” Hui Lau Lima News, 6 December 1959, 1; and Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 29 December 1959, 1-B.

[55] See Britsch, Moramona, 318.

[56] Linnel Taniguchi, interview by Gary Davis, 10 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[57] Billy and Kanani Casey, interview by Gary Davis, 18 March 2017, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Oral History Project, BYU–Hawaii Archives.