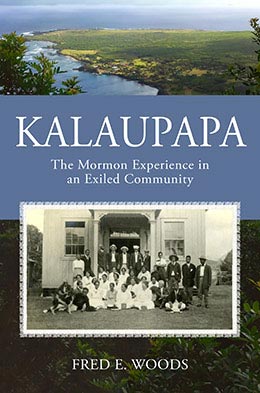

Mormons at Kalaupapa in the Late Twentieth and Early Twenty-First Centuries (1965-Present)

Fred E. Woods, "Mormons at Kalaupapa in the Late Twentieth and Early Twenty-First Centuries (1965-Present)," in Kalaupapa: The Mormon Experience in an Exiled Community, Fred E. Woods (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 215-256.

As the decades rolled on, all Kalaupapa denominational church assemblies decreased along with the settlement’s population. Yet during the latter half of the twentieth century, an abundance of LDS Church records verify that devout Latter-day Saints continued to pay tithing, partake of the sacrament weekly, and faithfully attend Sunday School and other auxiliary meetings. One record from 1965 contains the names of twenty-three people in attendance at a Sunday School meeting. Ten years later, only fifteen members were in attendance, evidence of a dwindling membership during this decade.[1] Yet LDS Church guest register books reveal that hundreds of people from various faiths continued to visit the Kalaupapa chapel.[2] As the decades rolled on, a waning of ecclesiastical activity among all Kalaupapa denominations continued.

Lions Club Impacts Patients

During the late 1960s, the Lions Club continued to impact the community. For example, during the month of March of 1969, the club sponsored a weekly settlement cleanup project. Residents were invited to donate their time and tools. A poster read, “We welcome everyone who wishes to volunteer their service by assisting the Lions Club in making our community as clean as we are able to do it.”[3]

Another Lions activity sponsored in late December of this same year was a hobby show held in Paschoal Hall. An advertisement clarified that it was not a competition, and all were welcome: “This is not a contest, but a very special showing of your personal collections. . . . We welcome anyone who wishes to enter this hobby show. . . . You’d be surprise[d] that people are deeply interested in seeing and admiring what you have. Anyone is welcome to enter.” Such thoughtful activities brought camaraderie and greater confidence to the community.[4]

The Sings

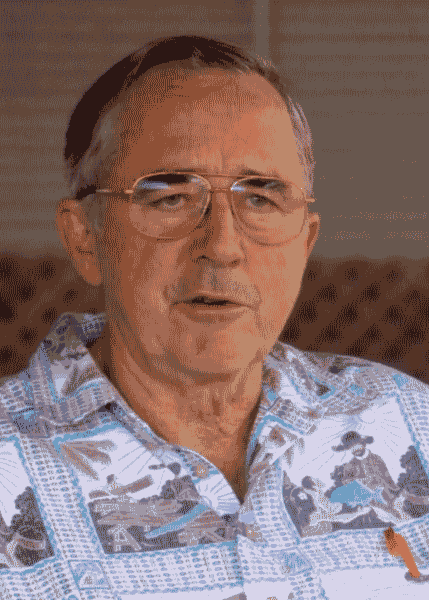

Jack Sing Kong. (Courtesy of Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii.)

Jack Sing Kong. (Courtesy of Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii.)

As mentioned in an earlier chapter, Jack Sing had been an active member of the Lions Club organization since its founding and was a welcoming friend to all. His wife, Mary Sing, served by his side, and together they blessed both residents and visitors with their service and optimism, spanning several decades. Mary had arrived at Kalaupapa in 1917, two years before Jack. Like Jack, she spent decades serving as a leader in the settlement, presiding over the Relief Society organization for at least two of those decades. It was said of Jack that he never missed presiding over weekly sacrament meetings during his thirty-one-year tenure as branch president, between 1952 and 1983.[5] Jack and Mary both passed away the same year at the Kalaupapa hospital—Mary in January at age eighty-two, and Jack the following December at the age of ninety-one.

Jack and Mary Sing. (Courtesy of Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii.)

Jack and Mary Sing. (Courtesy of Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii.)

Because of Jack’s exceptional service, he was publicly recognized in 1978 when he received the BYU–Hawaii Distinguished Service Award. In an address honoring Jack, President Jeffrey R. Holland (then president of BYU in Provo, Utah) said, “He was a major strength in the Church in Hawaii, due to his example of consistent, preserving service to others.”[6] Dan W. Andersen, then executive vice president at the BYU–Hawaii campus in Lā‘ie, on O‘ahu, where the award was bestowed, noted in the formal presentation the following:

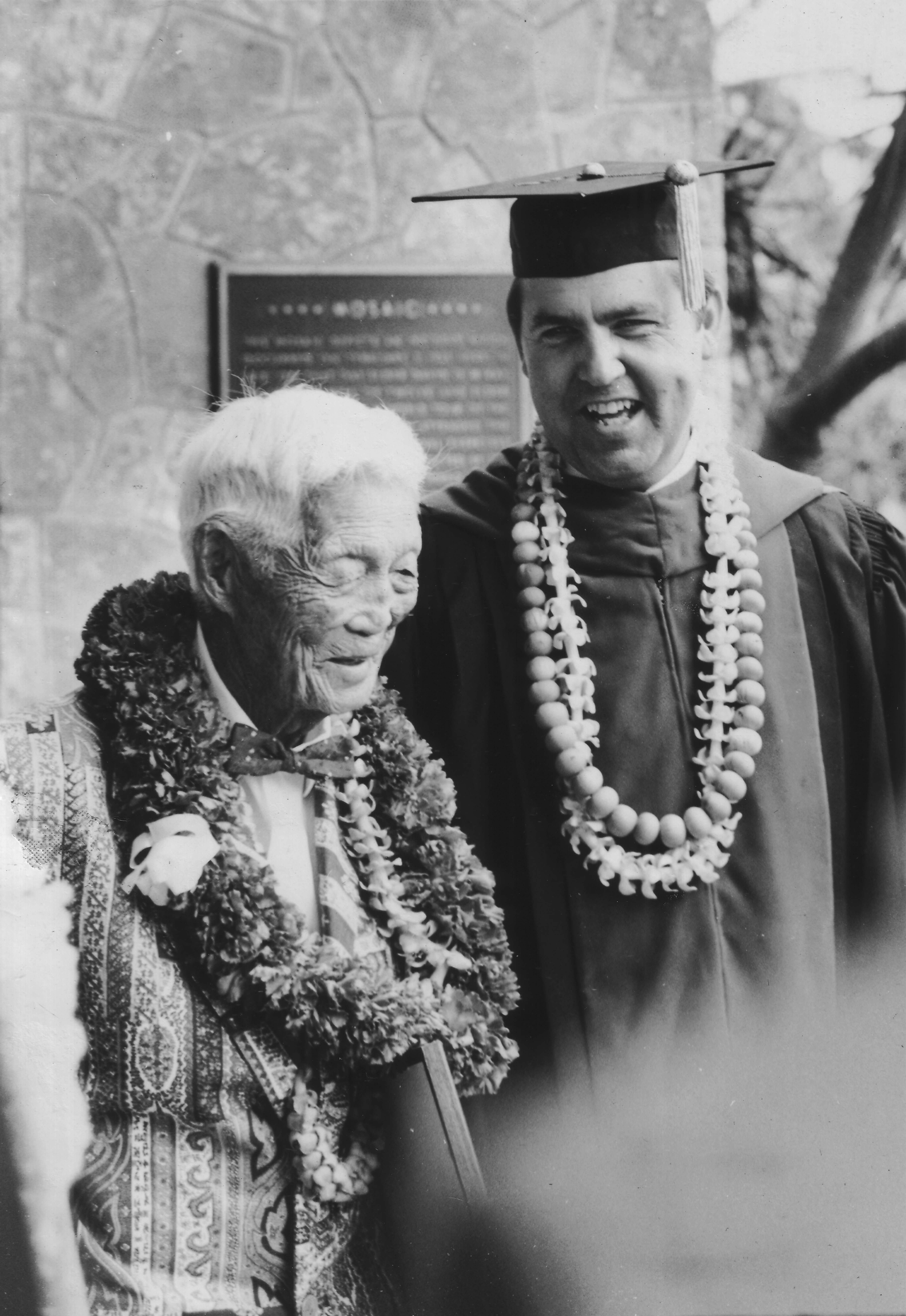

Jack Sing and Elder Jeffrey R. Holland in 1978 when Jack received the BYU–Hawaii distinguished service award on their campus in Lā‘ie. (Photo by Ishmael Stagner.)

Jack Sing and Elder Jeffrey R. Holland in 1978 when Jack received the BYU–Hawaii distinguished service award on their campus in Lā‘ie. (Photo by Ishmael Stagner.)

For his great courage and selflessness in overcoming the effects of one of the most dreaded and feared diseases in the world; For his willingness to share his time and generosity with visitors to Kalaupapa despite the possible embarrassment from the effects of the disease; for his more than twenty-six years of faithful devotion to his calling as a Branch President, his forty-four years as a church member, his forty-six years as a husband, his fifty-nine years as a Kalaupapa resident, store keeper, political party official and Lions Club founder, officer and member; and for nearly eighty-six years of a life dedicated to showing that the human spirit can overcome the ravages of physical scarring and disfigurement, and soar to heights of courage, compassion, and service, the Brigham Young University–Hawaii Campus is pleased to award its 1978 Distinguished Service Award to Jack Sing Kong.[7]

Jack’s response to the crowd’s standing ovation was quite modest. As he stood in sneakers, wearing a suit and speaking creole English, he said, “I like to say a few words and not only take this award as easy as it is handed to me. I very happy! This is the greatest honor I’ve ever had in my life. . . . Serve others. Preach the gospel of repentance. Live a righteous life. This is a beautiful world He made for us!”[8]

Although Jack has been gone for decades, his life made a difference then, and it inspires now. Jack presided over church meetings, helped keep the LDS Kalaupapa Cemetery groomed, and kept the church grounds in good order, including a small lodging house for the missionaries. “I like missionaries come,” Jack said. “I have food, beds ready. They welcome.”[9]

But clearly, Jack’s impact wasn’t confined to those of his religious affiliation. His service through the Lions Club and his warm, loving personality influenced the entire Kalaupapa community. John Arruda said Jack Sing was “what they call the pillar of the Lion’s Club, and the Mormon Church, and the Settlement.”[10] Another remarked that Jack was “a tradition at Kalaupapa, its acknowledged host, social leader, and unofficial mayor. . . . He had been the local storekeeper, [a] founder of the Lion’s Club, Republican precinct chairman, and unofficial VIP guide in the settlement.” Speaking of hosting these important visitors, Jack confessed, “I had a Cadillac, . . . and I used to take them around.”[11]

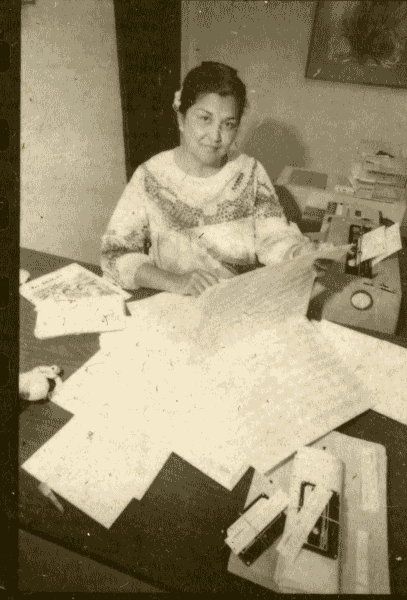

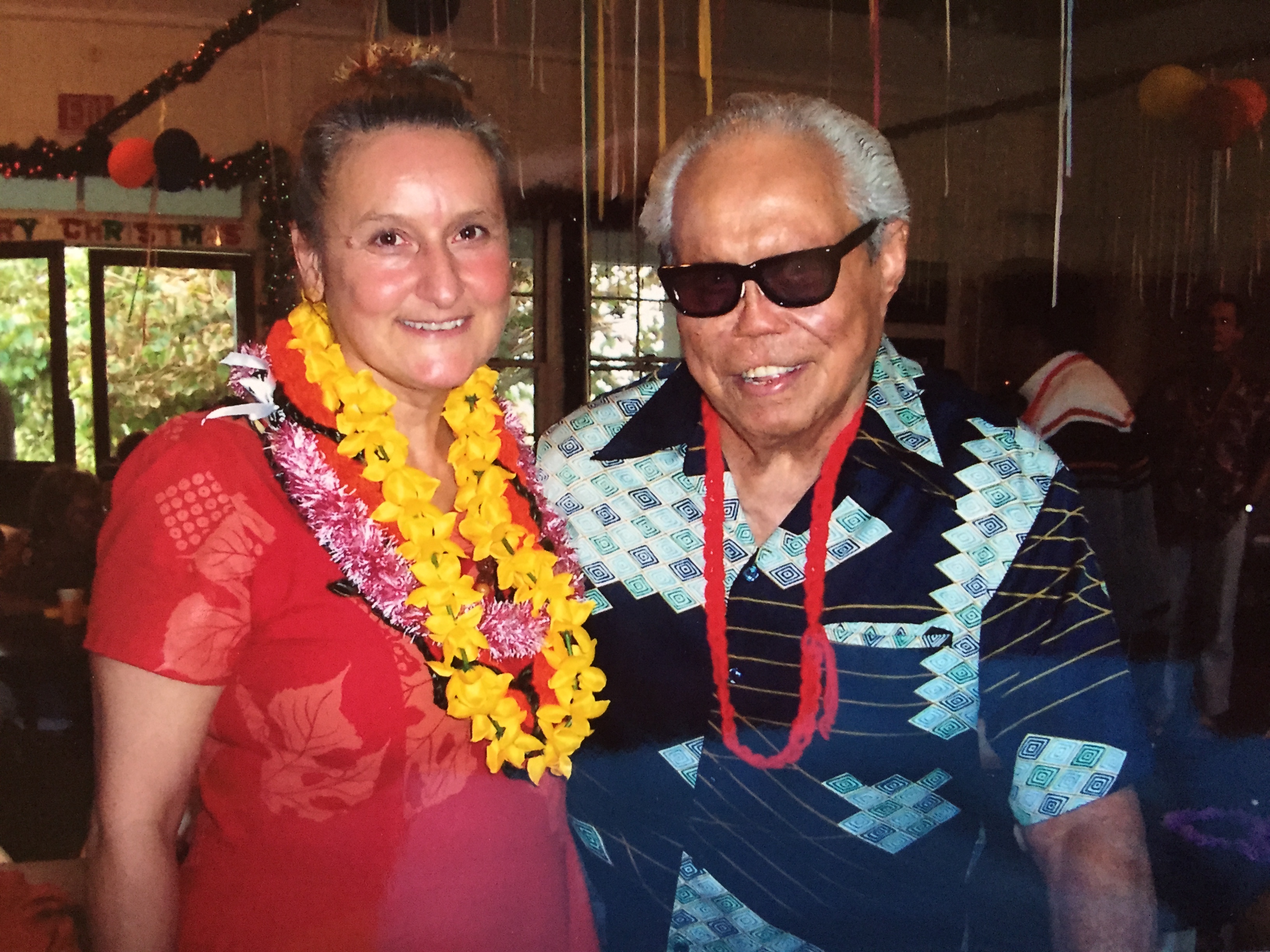

Nancy Talino and Fred E. Woods, 2006 at Hale Mōhalu. (Photo by Larry Lau.)

Nancy Talino and Fred E. Woods, 2006 at Hale Mōhalu. (Photo by Larry Lau.)

A Catholic patient, affectionately called “Boogie,” described Jack as “a holy man.”[12] Richard Marks recalled, “Everybody knew Brother Jack. . . . He was the most influential man in Kalaupapa. . . . He was a very important part of the community. [Jack and Mary Sing] were good people. Good people who were religious, who were examples for the [Mormon Religion].”[13] Nancy Talino, a Protestant patient, noted, “[Jack] was a good person. He always greeted all the people with a lot of love. Mary Sing was small and quiet, but you knew he loved her. Jack always had a smile.”[14] Ku‘ulei Bell also remembered Jack’s giving nature. She remembered that each Christmas, he brought chocolates to the Kalaupapa community.[15]

Although Saints like the Sings have passed on, their respectable, loving behavior remains an example to all who hear or read of their lives. As leaders of the Kalaupapa congregation, the Sings spent their lives striving to lift their fellow Saints and were continually looking outside the circle of their faith to bless the lives of the entire community. Testimonies shared in Church meetings with fellow members were important to bolster faith, but their consistent living of a day-to-day Christian life trumped the profession of mere words.

Jack Sing’s Final Years of Service

LDS Church records covering the final four years of Jack’s service as branch president of the Kalaupapa Saints indicate that sacrament meetings were held weekly despite the dwindling numbers of attendees. Samples of the minutes for 1979 consistently show that LDS meetings followed general Church protocol: they were held weekly, prayers were offered, several hymns were sung, and the sacrament was administered. However, due to the small numbers, only one member was selected to speak per meeting. And the scarcity of priesthood holders often necessitated Jack doubling up to both preside and conduct.

For the date of February 25, 1979, sacrament meeting minutes show that prayers were offered by Lucy Kaona (invocation) and Peter Keola (benediction). The speaker for the day was Rachel Nakoa. Jack Sing presided and conducted, and Jack and David Kupele blessed and passed the sacrament to the small congregation.[16]

Peter Keola and Ellen Rycroft McVeigh Hall. (Courtesy of NP Kalaupapa Archive.)

Peter Keola and Ellen Rycroft McVeigh Hall. (Courtesy of NP Kalaupapa Archive.)

Mormons worldwide observe the first Sunday of each month as a day of fasting—a day to abstain from two meals in order to increase spirituality but more especially to donate money saved from the foregone meals to the poor and needy. Meetings on this Sunday are referred to as “fast and testimony meetings.” There is no assigned speaker; rather, anyone in the entire congregation can voluntarily stand in turn and express their thoughts and testimonies about God and his gospel.

Minutes for the “Fast Meeting,” March 4, 1979, illustrate Kalaupapa’s peculiar confines:

Presiding: Jack Sing

Conducting: Jack Sing

Invocation: Jack Sing

Blessing and Passing of Sacrament: Jack Sing[17] (normally done by at least two men)

Three members of the congregation then shared their testimonies: Sister Mary Sing, Sister Lucy Kaona, and Brother Peter Keola.[18] Though small in numbers, the faithful believed a scriptural adage that where two or three are gathered, the Lord will be in their midst (Matthew 18:20). Personally, having been to a number of Kalaupapa LDS Church meetings with Lucy, Peter, and Ku‘ulei, I am confident that their expectations were met.

Sometimes events would spark topics for speakers to address at Kalaupapa sacrament meetings. For example, one Mother’s Day, there were three speakers. Mary Sing spoke on “Eve, the mother of all”; Ku‘ulei Bell spoke on “how wonderful my mother was to give me the gospel of Jesus Christ”; and the third speaker, Jack Sing, spoke on “the sad day when he had to come to Kalaupapa [and] his mother sold his pigs to give . . . money for him.”[19]

Johnny and Lucy Kaona, Cemetery Marker. (Courtesy of NP Kalaupapa Archive.)

Johnny and Lucy Kaona, Cemetery Marker. (Courtesy of NP Kalaupapa Archive.)

On March 9, 1980, Lucy Kaona was listed in Church meeting notes as giving a Sunday School lesson from a standard Church manual to a few in attendance. Jack Sing and David Kupele again blessed and passed the sacrament. Mary Sing delivered her talk, and Ku‘ulei Bell closed the meeting with a benediction.[20] Another sampling of a fast and testimony meeting six months later records that once again, few were in attendance. Jack Sing and David Kupele administered the sacrament, after which testimonies were shared by Lucy Kaona, Ku‘ulei Bell, and David Kupele.[21]

Topside Support

This small band of Kalaupapa Saints persisted for decades with the continual support from the outside. Visitors included missionaries, as well as Latter-day Saints from topside Moloka‘i, throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. Much effort was exerted each Sunday by a number of people to make sure that the Saints had the blessings of Church programs, especially the partaking of the sacrament. This was particularly true after Jack Sing passed away in December 1983, because he was the last resident of Kalaupapa to fill the position of branch president for the congregation.

The following year, Roy Horner, bishop of the Ho‘olehua Ward, began to oversee the branch and made biannual trips in March and December to inspect the LDS Church premises and to meet with Church members. Part of his December trip was to allow each of the remaining members to declare their annual tithing each year. At the time of his service as bishop (1984–90), Bishop Horner also escorted Church dignitaries such as D. Arthur Haycock, who served as secretary to five LDS Church presidents. In addition, Bishop Horner accompanied several Church General Authorities to Kalaupapa, including Elders Derek A. Cuthbert and Yoshihiko Kikuchi.[22]

During the time he presided as bishop, Horner also assigned Thaddeus “Ipo” Albino to preside over the few remaining LDS Kalaupapa branch members. Ipo, then working for the mule transportation service to the settlement, would bring a change of clothes after leading tourists down the pali on the mule train so that he looked presentable before meeting with LDS Church members Ku‘ulei Bell, Lucy Kaona, and Peter Keola.[23]

Another who went to Kalaupapa during the Bishop Horner era was Winona Kaawa. From her Ho‘olehua Ward, she brought LDS youth who were seniors in high school. Winona noted that it was a very spiritual event for them and, for some, a turning point in their testimonies. Winona said that her students loved it. “The minute they got there they felt the spirit.” In observing these young people, Winona added, “It was a very, very spiritual and uplifting experience to witness these youth as some of them shed tears and took everything in. . . . They came back being more appreciative of the gospel and the things they had in life.”[24]

Her husband, Edwin, also went down to serve during this era in the late 1970s and early 1980s as the elders quorum president of the Ho‘olehua Ward. Edwin, with much feeling, said that Kalaupapa was “a very emotional place to go. The faith that these women had and Brother Jack Sing was amazing. They were so, so very faithful. They were there on time and they sing as loud as they can and they are reverent when you are teaching or conducting a meeting.”

LDS Chapel and Social Hall, 2007. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

LDS Chapel and Social Hall, 2007. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

In addition to participating in these ordinances, Edwin Kaawa also cleaned the yard and repaired the roof, stairs, and ramp to the LDS social hall. He also did various repairs for Ku‘ulei Bell, which included replacing and painting her garage. Brother Kaawa made monthly trips to the settlement for a number of years and enjoyed his time mixing not only with the LDS congregation but also with members of the settlement in general. He considered it a privilege to come to the settlement and felt everyone was kind and generous. Edwin said Kalaupapa “was the most humble place anyone could go and visit. . . . I think even a wild man would be touched.”[25]

Throughout the late twentieth century, there were other LDS priesthood brethren climbing down and back up the pali each Sunday to serve and administer the sacrament. No matter how few the numbers, both the Saints receiving and the volunteers performing the ordinances felt uplifted. But these visitors came only for the weekends. During the regular weekdays, it was Ku‘ulei Bell who stepped up to render exceptional service to her fellow Saints. Although she did not have priesthood authority to officially bless and pass the sacrament, she was, for the Kalaupapa Saints, a woman for all seasons. According to Peter Keola, Ku‘ulei was “really something.” She not only provided counsel for her fellow LDS Church members she was also “a mother, a sister, [and] friend.”[26]

Ku‘ulei Bell and Lucy Kaona, 2005. (Photo by Lee Cantwell.)

Ku‘ulei Bell and Lucy Kaona, 2005. (Photo by Lee Cantwell.)

Church members from the LDS Ho‘olehua Ward on topside Moloka‘i were assigned to provide additional support. Those who made the journey to bring the sacrament to the Kalaupapa Saints recollect wonderful experiences, although coming down the steep Moloka‘i cliffs could be at times precarious and going up somewhat arduous. Esteban D. Arce described the hike: “Going down not too bad, I make it in forty-five minutes pretty good but coming up, oh boy, almost two hours.”[27]

During the late twentieth century, William “Yama” Kaholoaa, then second counselor in the elders quorum presidency of the Ho‘olelua Ward, made the trip up and down the pali weekly to help administer the sacrament. Although the hike for most was arduous, Yama, who was then in great shape, said he loved it. Administering the sacrament for him was a “most spiritual experience.” Yama recalled the voices of the patients echoing through the chapel as hymns were sung, and he noted, “I can still hear the echo of Sister Bell and oh so sweet. . . . She had such a strong voice.” Yama remembered that he felt the Spirit of the Lord very strongly and felt it was an honor to perform this service; to him there were no words to describe how special it was.[28]

Alex and Anna Bishaw also recalled going down the pali to bring the sacrament to the LDS patients: “She rode the horse down and I walked, and that was our transportation. . . . My wife did Relief Society with the sisters, and I did the priesthood with the brethren.”[29] Hannah Apo explained that she and her husband, Aloi, “went to Kalaupapa once a month, . . . sometimes twice when they needed help. . . . We got along fine with the Catholic priests there. . . . I think they know what we stand for.”[30]

Oliver Young, another priesthood holder living topside, made the trip back and forth. He remembered that when he first saw the patients in their difficult condition, an instant love for them came over him. Young said, “I really loved that place because of the patients.”[31]

Still another who made the journey was Timmy Meyer, who served the Kalaupapa Saints along with his wife, Donna, and others. Tim recalled, “When we went to Kalaupapa two elders would go with us, or our wives would go. We would usually hike down the pali and fly out, or we would walk back out. We would conduct services for the members. At any given time there would be only four to five members who always attended.” Tim explained that after making the trip down the trail the night before attending Church services in the settlement, “we would go out and visit less active members of the Church at Kalaupapa and invite them to the services. . . . On one occasion I had forgot my church pants, so I had to see a less active member and borrow a pair of pants. He gave me the pants to use and said that that was ‘part of him going to Church.’”[32]

Rod Felt also served the Kalaupapa Saints with his wife, Kerrie, and loved meeting with Ku‘ulei Bell, who first introduced them to the settlement and other members of the congregation. Rod recalled,

The Kalaupapa experience was a high point to us, . . . a singular experience. . . . On that first visit, Ku‘ulei wept as she talked about the patients who had enough of the disease to be sent to Kalaupapa. . . . We returned to Hawai‘i every year after that. . . . We brought our children and friends. It was important to us to see our new friend in the settlement. . . . We did not move here to Molokai until 2003. . . . After that we came frequently, volunteering to go to Kalaupapa to assist with Church meetings.

Although there are no longer any LDS patients living at Kalaupapa, some residents who work in the settlement remain interested in attending meetings. As of 2016, the Felts continue to make the journey.[33]

Cissy Fong, 2006. (Courtesy of Larry Lau.)

Cissy Fong, 2006. (Courtesy of Larry Lau.)

Musical Events Provided by LDS Church Members

Besides assisting with Church meetings, Mormon members from Lā‘ie donated their time and talents as hosts for musical and social events at Kalaupapa. Cissy Fong recalled that in the early 1980s, she, along with B. J. Lee and another pianist named Greg Tata, planned a program for the settlement and then went down to perform it. Of the experience, Fong said, “Not only were the people happy, we were proud of the LDS community. . . . It was exciting because the people there were so helpful, especially the people of the other churches, who came by and asked if there was anything they could do. . . . What a beautiful feeling it was to have everybody coming together.” She added, “After we went down that first time, then Ku‘ulei Bell had us come down [again] to play music. . . . She had Father’s Day and Mother’s Day luaus almost every year. We were fortunate to go down several years to sing for her luaus and other occasions when she sang. Ku‘ulei invited B. J., Hanaloa Nihipali and me, and we always went down together.”[34]

Left to right: Cissy Fong, B. J. Lee, and Hanaloa Nihipali, ca. 1980s. (Courtesy of Cissy Fong.)

Left to right: Cissy Fong, B. J. Lee, and Hanaloa Nihipali, ca. 1980s. (Courtesy of Cissy Fong.)

Looking back on her experience going to Kalaupapa as a performer, B. J. Lee also described the impact of the settlement on her as she reached out on many occasions:

The flight to Kalaupapa . . . is always a thrill for me to visit that place at the end of the rainbow. I always say that the Lord made that island very special by adding the Kalaupapa Peninsula. The same path once flown was flown again like I never left Kalaupapa from the dozen times I’ve visited. . . . The feeling upon landing and spying a tiny terminal, friends waving, you are suddenly transferred into a sort of South Seas island adventure.

She later reminisced, “Returning from Kalaupapa is a renewal of life. You return richer with love for the unfortunate—the physically, spiritually, and emotionally unfortunate. You search your soul to assess values, your dealings with your family; friends, neighbors. What good one has done in the world.”[35]

Notable Events

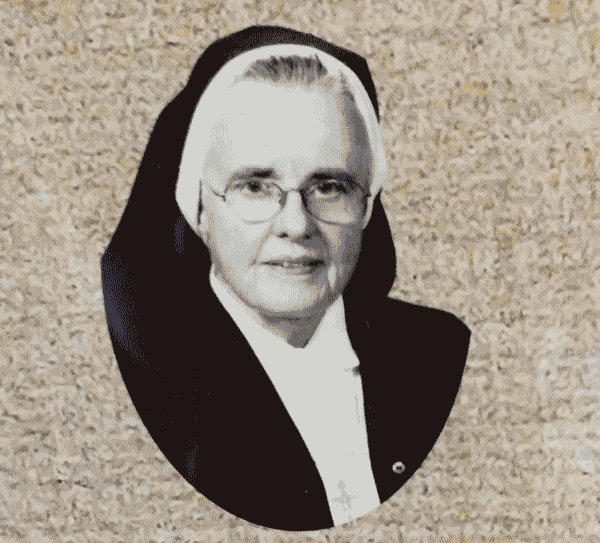

Ku‘ulei Bell and Pope John Paul II. (Courtesy of Lee Cantwell.)

Ku‘ulei Bell and Pope John Paul II. (Courtesy of Lee Cantwell.)

Although Ku‘ulei Bell was a Latter-day Saint, she was invited many times to sing in the Catholic choir. Not only did Ku‘ulei sing with a Catholic Kalaupapa choir but because she was the president of the Kalaupapa Residents Advisory Committee, Ku‘ulei was selected to be the Kalaupapa representative to meet Pope John Paul II at the time of the beatification of Father Damien in Brussels on June 4, 1995. Honolulu Star-Bulletin journalist Mary Adamski explained that Ku‘ulei was one of fourteen from Hawai‘i who played various roles in the beatification ceremony, which was attended by many, not the least of whom was Mother Teresa. Adamski described Ku‘ulei’s assignment and her memorable encounter with the Pope and Mother Teresa:

Her job was to present a 54-inch wili lei of lehua blossoms and kukui tree leaves crafted by Raymond Wong of Honolulu. The advance instruction was that an aide would accept the lei and other gifts, but Bell went with the mood of the moment. “The pope put his hand out and I kissed his ring,” she said. “They told me, ‘You not allowed,’ but when he bent his head down, then I put the lei over his head . . . and kissed him on the cheek. I said I come from Kalaupapa. He said, ‘Damien.’ That is all he said to me. He gave me a blessing and a rosary.” Catholic members of the group later made a bid for the rosary, Bell said, but she saved it for her Catholic granddaughter.

“It is one of the best memories of my life, the nicest experience I ever had,” said Bell, Kalaupapa postmistress, of the day in which she kissed the pope on the cheek and gave Mother Teresa a hug and a kiss. “It was kind of sacred, you know?”

“Mother Teresa was coming out of the cathedral. She was walking with two nuns,” Bell recalled. “I told the folks, ‘That’s her!’ I went to run to her. I hugged her and kissed her. I told her I come from Kalaupapa. She said the same thing: ‘Damien.’ She gave me one blessing. I kissed her hand.”[36]

Years after the beatification ceremony, Ku‘ulei and her dear LDS friend Lucy Kaona continued to make many trips to Father Damien’s Church in Kalawao (St. Philomena), three miles from Kalaupapa. There, with crystal-clear acoustics, they sang hymns to Father Damien as a tribute to his charitable service.[37] One song they especially enjoyed singing was a famous Mormon hymn, “I Am a Child of God.”[38] This hymn exemplifies the voice of the entire Kalaupapa community: “We are children of God.”

Ku‘ulei and Lua singing together in the St. Philomena Church.

Ku‘ulei and Lua singing together in the St. Philomena Church.

Another big event that rallied the community was the making of the film Molokai: The Story of Father Damien in 1999 at Kalaupapa. This film, directed by Paul Cox, was filmed on location and featured such Hollywood stars as Kris Kristofferson and Peter O’Toole. The patients mixed freely among the stars and production team and eagerly donated their time out of respect for the loving Belgian priest.[39]

Ku‘ulei Bell and Peter O’Toole and other Kalaupapa residents. (Courtesy of NPS/

Ku‘ulei Bell and Peter O’Toole and other Kalaupapa residents. (Courtesy of NPS/

Free to Go, Free to Stay

In 1969, the same year that Neil Armstrong took a giant step onto the moon, the Hawai‘i Board of Health finally made the move to permanently end the isolation of all patients.[40] In spite of this significant decision, which lifted the ban, many patients chose not to leave. Others left Kalaupapa and tried to assimilate into society, but they found that life was better in the settlement and returned “home.” This was a time of realization and reflection for the patients. Each discovered, in their own time, that they had fashioned a paradise out of a hell.

Over the years, the Kalaupapa community had been sanctified through suffering. One former patient, Bernard Punikai‘a, said that Kalaupapa used to be viewed as “a devil’s island, a gateway to hell, worse than a prison.” But he added, “Today it is a gateway to heaven. There is a spirituality to the place. All the suffering of those whose blood has touched the land—the effect is so powerful even the rain cannot wash it away.”[41]

Jack Sing noticed, “In Honolulu everybody for themselves—you have money you have friends, you have no money, you have no friends. Over here, . . . money no matter.”[42] Referring to the outside world of Honolulu and beyond, another patient, Makia Malo, observed, “They thought it [Kalaupapa] was hell and we thought it was heaven.”[43]

Some patients also found spirituality through combating their physical illness. Lee Cantwell, a former LDS missionary to Hawai‘i, told of his experience meeting a dying patient named Joe Kekahuna at Hale Mōhalu. Cantwell explained that when he met Joe, the patient was very disfigured and blind but strong in spirit. Before leaving his side, Cantwell remembered that Joe “turned his sightless eyes toward me and bore a tender testimony. ‘I’m glad I got this disease Elder,’ he said. ‘Before I went to Kalaupapa, I was a hard guy, I did everything bad. I had not time for God. Then I got this sickness and went to Moloka‘i, to Kalaupapa, where I had plenty of time. I found the gospel, I found brothers and sisters who loved me and understood me. It’s okay that I lost my health; I found something much better, something I will never lose.’”[44] After spending over forty years in the settlement, another male patient explained,

I don’t blame anyone for this disease, and I don’t feel bitter. It was God who sent me to Kalaupapa; it was His work. I found religion and my faith inside Kalaupapa. Today I am a Catholic. Before, I had started to drift away from the Church. On Maui as a Catholic, we were told not to associate with Protestants, and I thought that was too strict. But being a Catholic in Kalaupapa is better. So I am happy. I feel now is the happiest time of my life. Nothing will make me live outside Kalaupapa. This place is heaven.[45]

Kalaupapa’s Impact on Spirituality

Reflecting back over her years spent at Kalaupapa, one Protestant patient, Nancy Talino, told her experience of coming to have an intimate relationship with God:

We were nurtured. . . . Not just by a Protestant or a Mormon or even Catholic nuns. Everyone worked together. . . . Everyone needed prayers, there were prayers. And I was thankful that I was very close, very close to God. . . . Someone asked, “Do you ask God why?” I said, “No, I don’t.” I just say, “Maybe it’s a wake-up call.” I thank Him. . . . I want people to know, really know the love in the hearts of the people of Kalaupapa. . . . We’ve got hearts. We’ve got hearts.[46]

In another interview, Nancy described the ecumenical nature of attending different churches in the settlement on Sundays and on other weekdays:

We had a lot of children of different races and different creeds. Everybody belonged to a different church, but every Sunday we started off with Mass at six o’clock in the morning. Nine o’clock we’d go to Protestant church. Sunday afternoon we would go to the Mormon Church, and then Monday evening there’s another church service, it could be a Filipino church service. And then there’s another one during the week, . . . a Buddhist.

Nancy also praised the staff and again gave profound thanks to God:

The staff . . . brought so much love into our hearts. And though we suffered, it was a lot of pain and suffering, a lot of tears, but I can look back and thank God for those tears because for many of us it brought us closer to Him, and through the years it nurtured our lives. We can think back and say, for one thing we were close to God. God kept us these years, and that is the reason why we are still here today. God kept us. And many of us can truly say, without his love, we would not be here. Many times I think about the people who brought all that love into our hearts. I know even though they’re not here with us, I can still thank them, thank them with all my heart, because they were a part of our lives. They’re really looking down on us. We had a lot of good doctors there and the nuns also. But there was a lot of joy and happiness, a lot of young people also. But God kept us through all these years and really how thankful we are. I guess so many of us now can think back and say, “Well, in spite of the pain, God has still seen us through all that heartache and the pain. And we can still praise Him and thank Him.”[47]

Nancy Brede, 2006 at Hale Mōhalu. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

Nancy Brede, 2006 at Hale Mōhalu. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

Nancy Brede, another patient, who came to Kalaupapa in 1936 at age fourteen, shared her experience of prayer and the importance of expressing gratitude to God, even in times of adversity:

God knows best for us. . . . You must keep your faith no matter what comes into your life, you must still be able to thank the Lord for the many other blessings that we receive, and keep this faith all the time, no matter what comes into our life. Yeah.—Cause I feel religion is not thanking God when everything is good; religion is thanking God when everything isn’t going right.[48]

Common Calamity Brings Spirituality and Unity

Several people who had contact with the Kalaupapa patients spoke of the unifying effects which appear to be inherent in the suffering of this disease. For example, in his book Travels in Hawaii, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote of his visit to Kalaupapa, remarking, “They were strangers to each other, collected by common calamity, disfigured, mortally sick, banished without sin from home and friends.” He further noted, “Few would understand the principle on which they were thus forfeited in all that makes life dear; many must have conceived their ostracism to be grounded in malevolent caprice; all came with sorrow at heart, many with despair and rage. In the chronicle of man there is perhaps no more melancholy landing than this.”[49] Yet he added that among the “sights of pain in a land of disease and disfigurement, bright examples of fortitude and kindness, moral beauty, physical horror, intimately knit.”[50] They were not to be overcome, and as a result of their collective cooperative experience, they became one, which could not go unnoticed.

Journalist Ernie Pyle recalled, “My stay on Kalaupapa was one of the most powerful adventures in my life. . . . It was a feeling something like this: out of the defilement and abuse that nature had heaped upon those people, there had arisen over Kalaupapa an atmosphere that was surely spiritual, almost heavenly. It was a strange atmosphere of calm—a calm that was invitational, and almost irresistible.”[51]

Ethel H. Damon was also discerning, saying, “Surely the isolation of suffering has tended toward obliterating the barriers in religious observance.”[52] Reverend James Drew further observed, “They are brothers and sisters here. . . . Leprosy has made sure of that.”[53] Paul Harada, a Japanese patient, echoed this same theme: “The more we suffer, the more strength we have. The more suffering, the closer we are together. Life is that way. If you haven’t suffered, then you don’t know what joy is. The others may know something about joy, but those who have gone through hell and high water, I think they feel the joy deeper.”[54] In referring to the Kalaupapa community in another setting, Harada said, “We are all friends. There is an ecumenical philosophy here.”[55] Commenting about his life in a paradise amid the Kalaupapa community, Jack Sing said simply, “We are all brothers and sisters. . . . We help each other.”[56]

The Kalaupapa ‘Ohana

While reminiscing about the sixty-plus years of living at Kalaupapa, Mary Sing recalled, “Everybody was living just like a family. Nobody says anything bad about the other religion. Everybody was together. See, they respected, you know, each church.” Mary added, “If the Catholic had a party, . . . they wait for the Mormon people to get through with their service. . . . And so [it] is with the Protestant, everybody was happy.”[1]

This description of the Kalaupapa ‘ohana (family) happiness was also expressed by Edwin Lelepali, affectionately known as “Pali,” who was sent to Kalaupapa in 1942. Pali expressed his joy and gratitude when members of the settlement joined in 1966 to help reconstruct the Protestant Siloama Chapel; in the same manner, they had assisted the Mormons in building their house of worship the previous year. Pali noted, “We had the Protestants, we had the Catholics, we had the Mormons all chip in to build this Church. . . . They wanted to help this Church. . . . When you came here you could feel the spirit of love. It was special working with them. . . . It was just beautiful. I can never thank them enough. It was wonderful.”[57]

Edwin “Pali” Lelepali at Kalaupapa Cemetery, where his wives and dogs are buried side by side. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

Edwin “Pali” Lelepali at Kalaupapa Cemetery, where his wives and dogs are buried side by side. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

When asked if the same was true when a twentieth-century Catholic church was erected, Pali added that all joined in “to help raise some funds for the Church. . . . Everybody would help out and that’s how it was in Kalaupapa. That’s what’s so different about Kalaupapa, when somebody needs help, everybody’s there.” Pali further explained, “This is our family. . . . I don’t care what religion. . . . That’s how we felt. When they need help, we [are] there, see? . . . We always go. You don’t have to ask us, we just come out and help. That’s how we were brought up here in Kalaupapa. Somehow that great love for everybody brought us together.”[58]

Pali not only assisted in erecting buildings but also in lifting people. Besides being a leader in his Protestant church activities, he has been one who is continually thinking of the community. For example, for decades Pali has made sure that every woman in the settlement was given flowers on Mother’s Day.[59] In a place where women had to immediately give up their babies upon delivery, this kind act no doubt brought comfort to those in great emotional pain.[60] Such pain, however, did not go away completely. Ku‘ulei Bell shared her pain when family members brought her little boy for a visit to the settlement, and he asked, “Mommy, why do you have to be in that cage?” referring to a barrier erected so that there was no physical contact between mother and child.[61]

Power of Pets

To help fill the emotional void of having children and family taken from them, patients developed special bonds with their pets to ease the pain. A visit to the settlement was all one needed to see that the patients fulfilled their human need to love in their pets. Ku‘ulei almost “wore” her beloved Ming Toy. If he wasn’t in her lap, he would surely be at her feet. He was even a welcome attendee at church. Wherever Ku‘ulei went, Ming Toy went. Mormon visitors to the LDS chapel at the settlement remember the appearance of pets during services, a sight singular to Kalaupapa which has been a delight to those who have witnessed such a display. For example, in 1961, D. Arthur Haycock (former LDS mission president to Hawai‘i, 1954–58) responded to an affectionate letter from Jack Sing, telling Jack, “I am glad to know Tiny [Jack’s dog] still goes to Church every Sunday though he is a rascal.”[62]

Kalaupapa LDS Chapel, 2007. (Courtesy of Brian Wilcox.)

Kalaupapa LDS Chapel, 2007. (Courtesy of Brian Wilcox.)

If you were a pet, you’d want to live at Kalaupapa. A trip to the cemetery speaks volumes about the intimate relationship between pets and their owners; pets lie buried right beside their loving caregivers. Such is the case with Pali’s dogs, who are buried beside his wives. Pali shared his feelings: “Since you cannot have children, . . . all the animals become like children. Cat, dog, anything. We sort of draw to them. We take good care of them. They are like our children because we can’t have children. . . . You’d be surprised how we hold on to our animals.”[63]

Ivy Kahilihiwa, another patient, sent to Kalaupapa in 1956, said, “We don’t have children, . . . and yet you notice the dogs are just like children, and the cats too. When we talk to the dogs, the dogs listen to us, and the cats too. They understand our language, you know.”[64] Another patient, Gertrude Kaauwai, who was known in the settlement as the “cat woman,” explained her tender feeling about many settlement animals she fed daily: “When I came here and I saw cats and rabbits and all kinds of animals. I see a lot of them starving, . . . so that made me feed those animals. Because they are hungry, . . . I go, I feed them. Then as I grew older, when I started to get my own house and married, I started to go all different places and feed cats and feed dogs. . . . That’s why they call me the cat woman.”[65]

The Spirit of an Ecumenical Community

Richard Marks, a former patient, a Catholic, and the sheriff of Kalaupapa for nearly two decades (proud of his record of “no arrests”), related a humorous anecdote.[66] In describing the Christmas Catholic mass at Kalaupapa, Marks explained, “The Protestants and the Mormons came early and they took the back seats so we had to sit up front.”[67] Boogie, another patient of the same faith added, “We know all about the things we went through. . . . I think that’s one [reason we feel like a family]. . . . When we had a function going on, the whole community just comes together.”[68] One patient, a very active member of the Protestant community, recalled, “Us and the Catholic Church and the Mormon Church, we’re always getting together. When it was something big, we always join together and enjoy it.”[69]

Preserving the Land and History of Kalaupapa

In 1980, the US Department of the Interior and National Park Service established the Kalaupapa National Historic Park to preserve the historic buildings and heritage of this unique community. One of the stipulations for the creation of the park was that the patients would be able to live at Kalaupapa as long as they wanted and that their lifestyle and privacy would be protected.[70] Two years passed, and Bruce Doneux, a volunteer paramedic, along with the support of many patients, spearheaded the founding of the Kalaupapa Historical Society for preservation purposes,[71] which was followed two decades later by the creation of Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa (The Family of Kalaupapa).

This nonprofit organization, established in August 2003, is dedicated to endorsing the dignity and worth of every one of the eight thousand plus patients exiled to the Kalaupapa peninsula commencing in 1866 (over ninety percent of which were native Hawaiians). Ku‘ulei Bell was elected as the first president and continued in her office until her passing in 2009. Concerning this patient-led association, Ku‘ulei said, “This organization is wonderful—it’s not just patients, but it’s family members and people who have supported us for so many years. We are one ‘ohana, working together to make life better for the patients and to preserve the history so people in the future will remember those who have passed on.”[72] Henry Nālā‘ielua summed up the predominant message culled from years of early annual Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa meetings: “To see this place stay sacred.”[73]

Conclusion

The Kalaupapa community as a whole sends a powerful, universal message, regardless of one’s ethnicity or religiosity. Orson F. Whitney, a Mormon Apostle, explained, “God has been using . . . other peoples of the world as well, to carry out a work that is too demanding for the limited numbers of Latter-day Saints to accomplish by themselves. . . . Other good and great men and women . . . have been inspired of God under many circumstances to deliver dimensions of light and truth.”[74]

Such was the case at Kalaupapa, when people who suffered a “common calamity” joined hands to forge a magnificent community that reached across borders. Ignorant outsiders may have referred to the Kalaupapa patients as “untouchables,” yet everyone who ever visited the settlement was touched and transformed by them.

Kalaupapa’s society is an extraordinary sermon. At least a portion of it might be captured through a touching speech Lawrence Judd made during his first Christmas season at the settlement. Here, Judd revealed his tender feelings concerning the Kalaupapa community: “I know of no land nor people who can grow into one’s heart more than Kalaupapa and its people. I am sure God smiled with great delight when he finished Kalaupapa. He left with it and its people much of his love and the beauty of his own soul. I feel certain he built himself into it and has since glorified it with his frequent presence.”[75]

Likewise, I can still hear the voice of my deceased friend Ku‘ulei Bell ringing in my head, describing the uniqueness of this sacred settlement. In my last interview with Ku‘ulei, just a month before her passing, she said, “There is no other place, no other place in the world, like Kalaupapa. The serenity, it’s beautiful. The people, they have their own peacefulness. The way you see them, even when they’re sick, they still love. They greet each other, help each other, they comfort each other. This, to me, is beautiful.”[76] In an additional testimony to the distinct makeup of the settlement, Henry Nālā‘ielua emphatically declared, “There is no place like Kalaupapa. You’re gonna feel it.”[77]

I have come to discover that Lawrence Judd, Auntie Ku‘ulei, and Uncle Henry were right. I, for one, have witnessed Kalaupapa’s beauty and felt its power again and again. What I have learned the past dozen years of exploring the soul of Kalaupapa is that her sum total as a community is greater than her parts. I have also come to understand that the Mormons were not a separate part of the settlement; rather, they were an integral part of Kalaupapa’s spiritual fabric woven into every fiber of this unique community, along with strands contributed by other faith traditions. From the days of Napela joining hands with Damien to the time of Ku‘ulei helping launch Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa, there has been a strong connection between the Mormons and the Kalaupapa community. It’s a connection I have experienced intimately and will forever retain. I am one of many Latter-day Saints who is grateful for the touch of the Kalaupapa community—a touch that has left her fingerprints deeply embedded in my heart.

The story of Kalaupapa is an epic tale of human triumph. It begins as a tragedy and culminates in a storybook ending. A devastating plague ravishes a population, but then a community is forged in love, free of universal ignorance, prejudice, and pride. The separating sickness that initially tore people away from those they loved subsequently united them with strangers who became their ‘ohana. The community of Kalaupapa achieved what has yet to be accomplished in any society I know of. Healthy or sick, brown or white, bond or free, Catholic, Protestant, Buddhist, or Mormon, all were equal and beloved. Each denomination lived above their precepts and pleased God in the process. Heroes walked among the patients. Men and women offered and risked their lives to assure the well-being of patients and to tenderly minister to the destitute. Regardless of one’s ethnicity or religiosity, the story of Kalaupapa delivers a powerful universal message: “In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, and in all things, charity.”[78]

Notes

[1] . Deseret Sunday School Roll, 1965, “Roll of Attending and Potential Members,” Kalaupapa/

[2] . A copy of these visitor registers is in the possession of the author. Some visitors came for church meetings or funerals, while others came to just see the buildings.

[3] . Timothy Waiamau, Chairman, “Kalaupapa Settlement Clean-Up Work,” 1969, Kalaupapa Lions Club Activities KALA 20776/

[4] . Timothy Waiamau, Chairman, “Hobby Show,” 1969, Kalaupapa Lions Club Activities KALA 20776/

[5] . Vernice Wineera, Jay Fox, and B. J. Lee, “Jack Sing Kong Kalaupapa Pioneer,” University Magazine, BYU–Hawaii, Winter 2001, 43. An LDS Church minute book for the years 1979‒83 (handwritten in a notebook filled almost completely with reports of weekly sacrament meetings) reveals that during the last four years of his life, Jack presided over and conducted many sacrament meetings. Though consistent and outstanding, apparently he was not perfect in attending, probably due to declining health in his old age. The author has in his possession a copy of these records for the years 1979‒1983, hereafter cited as Church Meeting Minute Book, 1979‒83.

[6] . “Jack Sing Kong, Mark E. Petersen, Giants of an Era,” Hawaii Record-Bulletin (January–February 1984), 4.

[7] . BYU–Hawaii 1978 Distinguished Award verbiage signed by Dan W. Andersen, courtesy of Jay Fox, who was serving as the academic vice president of BYU–Hawaii at the time of the presentation. Notes taken by Vernice Wineera during a visit with Jay Fox at the Kalaupapa settlement in 1982. The author expresses appreciation to Jay Fox for giving him a copy of these notes, which are in the author’s possession.

[8] . Wineera, et al., “Jack Sing Kong Kalaupapa Pioneer,” 46.

[9] . J. Malan Heslop, “Leper Colony His Home for 57 Years,” Church News 47, no. 3 (January 15, 1977).

[10] . John Arruda and Paul Harada, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 29, 2006, Kalaupapa.

[11] . Wineera, et al., “Jack Sing Kong Kalaupapa Pioneer,” 42, 44. Nancy Talino recalled, “Jack was very proud of his Cadillac.” Nancy Talino, interview by Fred E. Woods, January 18, 2015, Hale Mohalu.

[12] . Clarence “Boogie” Kahilihiwa, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, June 20, 2007, Kalaupapa.

[13] . Richard Marks, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 28, 2006, Kalaupapa.

[14] . Nancy Talino, interview by Fred E. Woods, January 18, 2015, Hale Mōhalu. To her credit, Mary Sing also served for over a quarter of a century as the president of the Kalaupapa Relief Society. See also Heslop, “Leper Colony His Home for 57 Years,” 4.

[15] . Ku‘ulei Bell, comment made to Fred E. Woods, Summer 2005, Kalaupapa.

[16] . Minutes of LDS Church meetings, February 25, 1979, Church Meeting Minute Book, 1979‒1983. These weekly minutes also note that Jack Sing and David Kupele administered the sacrament on a regular basis.

[17] . Visiting priesthood brethren also came regularly down the pali to assist with meetings. For example, minutes from the sacrament meeting on March 8, 1981, note that Elder Carmaro and Elder Alexander Bishaw both spoke in this meeting. Alex Bishaw still lives on topside Moloka‘i. (See Church meeting minute book, 1979‒1983).

[18] . Minutes of LDS Church “Fast Meeting,” March 4, 1979, Church Meeting Minute Book, 1979‒1983.

[19] . Minutes of sacrament meeting on Mother’s Day, May 10, 1981, Church Meeting Minute Book, 1979–1983.

[20] . Minutes of the “Sacrament Meeting of the Kalaupapa Branch,” along with minutes from the “Sunday School Meeting,” March 8, 1980, Church Meeting Minute Book, 1979–1983.

[21] . Minutes of a “Fast Meeting of the Kalaupapa Branch,” September 6, 1980, Church Meeting Minute Book, 1979–1983.

[22] . Roy Horner, phone interview by Fred E. Woods, January 18, 2016.

[23] . Roy Horner, phone interview by Fred E. Woods, January 18, 2016. See also Lance D. Chase, “Mormons and Lepers: The Saints at Kalaupapa,” in Proceedings, Thirteenth Annual Conference, Mormon History in the Pacific, May 16, 1992, (n.p.: Mormon Pacific Historical Society, 1992), 20.

[24] . Winona Kaawa, phone interview by Fred E. Woods, January 26, 2016.

[25] . Edwin Kaawa, phone interview by Fred E. Woods, January 26, 2016.

[26] . Peter Keola Jr., interview by Barbara Nakamura, August 6, 1999.

[27] . Esteban D. Arce, interview by Kenneth W. Baldridge, December 29, 1979, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection (OH-100), 24, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI.

[28] . William “Yama” Kaholoaa, phone interview by Fred E. Woods, January 18 and 20, 2016.

[29] . Alex and Anna Bishaw, interview by Fred E. Woods, February 13, 2015, Moloka‘i Family History Center. Alex also mentioned in his interview that he played the ukulele for the patients. Now at age 90, he can no longer do so.

[30] . Aloi and Hannah Apo, interview by Kenneth W. Baldridge, August 19, 1980, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection (OH-133), 24.

[31] . Oliver Young, interview by Fred E. Woods, April 18, 2015, Hotel Molokai, topside Moloka‘i. Oliver was an LDS Church leader who provided service to the Mormon community commencing in the 1960s. He is now 87 years old.

[32] . Tim and Donna Meyer, interview by Fred E. Woods, February 12, 2015, Meyer residence. They live on topside Moloka‘i, where they have lived almost all their lives. Tim was a sergeant in the Moloka‘i police department, and his employment took him down to Kalaupapa. However, he also went to Kalaupapa to perform service for the small LDS community there.

[33] . Rod and Kerrie Felt, interview by Fred E. Woods, April 17, 2015, Felt residence. In an email the author received from Rod Felt on December 20, 2015, Rod wrote, “We have resumed holding weekly Sacrament Meetings at the Kalaupapa Chapel. Meetings have not been held in Kalaupapa since Ku‘ulei Bell, Lucy, and Peter left Kalaupapa.” This was joyous news to the author.

[34] . Cissy Fong, interview by Fred E. Woods, January 30, 2015, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI.

[35] . B. J. Lee, “A Memorable December Weekend in Kalaupapa,” handwritten on notebook paper, December 11‒12, 1982.

[36] . Mary Adamski, “Church Rites Rekindle Blessed Memories,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, last modified 2003, http://

[37] . There is little doubt that Ku‘ulei would have been present at Damien’s canonization ceremony in 2009, but she passed away eight months before it happened.

[38] . Larry Lau former (BYU–Hawaii employee) and Fred E. Woods spent portions of the summers of 2004 through 2006 filming Kalaupapa patients. During the summer of 2005, they filmed Ku‘ulei and Lucy singing “I Am a Child of God” in the St. Philomena Church. The author has a copy of this recording in his possession.

[39] . “Saint Damien of Molokai,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2006, http://

[40] . Greene, Exile in Paradise, xxx.

[41] . Tayman, The Colony, 315.

[42] . Wineera, et al.,“Jack Sing Kong Kalaupapa Pioneer,” 45.

[43] . Makia Malo, comment made to Fred E. Woods, Summer 2007, Kalaupapa.

[44] . Lee Cantwell, “The Separating Sickness,” This People 16, no. 2 (Summer 1995), 55.

[45] . Ted Gugelyk and Milton Bloombaum, The Separating Sickness Ma‘i Ho‘oka‘awale, (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Foundation and the Ma‘i Ho‘oka‘awale Foundation, 1979), 67–68.

[46] . Nancy Talino, interview by Fred E. Woods, August 7, 2006.

[47] . Nancy Talino, interview by Fred E. Woods, January 9, 2009, Hale Mōhalu, HI.

[48] . Nancy Brede, interview by Fred E. Woods, August 2, 2006, Hale Mōhalu, HI. Nancy was registered for seventy-nine years as a Kalaupapa resident, longer than any other patient who came before her. Nancy passed away at age ninety-two in the fall of 2015. For more of her story, see Pamela Young, “Oldest patient at Kalaupapa dies,” KITV4 Island News, posted October 30, 2015, http://

[49] . Robert Lewis Stevenson, Travels in Hawaii, ed. A. Grove Day (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1973), 53.

[50] . Stevenson, Travels in Hawaii, 51.

[51] . Ernie Pyle, Home Country (New York: William Sloane Associates, 1947), 244.

[52] . Damon, Siloama, 84.

[53] . Reverend James Drew, cited in Tayman, The Colony, 297.

[54] . Tayman, The Colony, 314.

[55] . Paul Harada, interview by Fred E. Woods, August 2, 2006, Kalaupapa.

[56] . Heslop, “Leper Colony His Home for 57 Years,” 4.

[57] . Edwin “Pali” Lelepali, interview by Fred E. Woods, February 9, 2007, Kalaupapa.

[58] . Edwin “Pali” Lelepali, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 29, 2006.

[59] . Edwin “Pali” Lelepali, conversation with Fred E. Woods, July 2006.

[60] . Hariet Ne recalled walking down to Kalaupapa weekly “to roll bandages at the Long house, that’s when they separate the women when they give birth to children. . . . They ship to Honolulu, to Kalihi, boys only. . . . The girls, they take . . . up to Pearl City.” Hariet Ne, interview by Kenneth W. Baldridge, July 30, 1987, Kenneth Baldridge Oral History Collection (OH-297), 10.

[61] . Ku‘ulei Bell, conversation with Fred E. Woods, July 2006. However, it is unclear what barrier Ku‘ulei is referring to as she came to Kalaupapa after Lawrence Judd had directed that the partition between patients and visitors be torn down.

[62] . D. Arthur Haycock, letter to Jack Sing Kong, December 4, 1961. This comment was precipitated by the fact that Jack had written to Haycock the previous month, noting, “We all send our aloha to you and Sister Haycock, I am sure Tiny [Jack’s dog] too. He still very rascal and goes to Church every Sunday.” Jack Sing Kong, letter to D. Arthur Haycock, November 10, 1961, copy of letter in possession of the author, courtesy of Lynette Haycock Dowdle and Brett D. Dowdle.

[63] . Edwin “Pali” Lelepali, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 29, 2006.

[64] . Ivy Kahilihiwa, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, June 20, 2007, Kalaupapa. Ivy still lives in Kalaupapa with her husband, Boogie, and their pet dogs.

[65] . Gertrude Kaauwai, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, June 22, 2007. Gertrude Kaauwai, or “Aunty Gertie” or “Girlie” as she was affectionately known, was born on Novemver 26, 1932, at Olowalu. At age 11, Gertrude was sent to Kalaupapa on September 27, 1944, where she was a resident for 66 years. She passed away on December 24, 2010. See Ka‘ohulani McGuire, “Gertrude Seabury Kaauwai of Kalaupapa, Dies at 78,” Molokai Dispatch, https://

[66] . Pat Boland made this humorous remark during his eulogy of Richard Marks on December 27, 2008, on O‘ahu: “Being the sheriff of the County of Kalawao, he would wear the badge when it was required, but he told me he didn’t know where the keys to the jail were.” However, Richard could be tenacious when he needed to be. In fact, in this same eulogy, Pat Boland explained that after Bob Maxwell, editor of Beacon magazine, visited Kalaupapa, interviewed Richard, and put him on the cover of the magazine (both in the February 1968 issue and again in January 1969) with the caption, “Man of the Year,” Richard’s courage and bold declaration “I am a leper” provoked an uproar in Honolulu. Boland maintains, “As a result, in 1969, Hawai‘i’s laws and rules were changed so that new patients would no longer be confined but would be treated as outpatients. This would have happened eventually, but the fact that it happened in 1969 is solely attributable to Richard.” Typescript copy of eulogy in possession of author.

[67] . Richard Marks, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 28, 2006, Kalaupapa.

[68] . Clarence W. K. “Boogie” Kahilihiwa, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 29, 2006, Kalaupapa.

[69] . Edwin “Pali” Lelepali, interview by Fred E. Woods, July 29, 2006, Kalaupapa.

[70] . “A Proposal for the Establishment of the Kalaupapa National Historical Preserve,” April 1980, excerpts from Basic Conclusions, 2, National Park Service, document in possession of the author.

[71] . “Kalaupapa Historical Collection Project & Newsletter,” no. 2 (November 1982), 1. This newsletter notes, “The organizational meeting for the Kalaupapa Historical Society was held October 21, 1982, in the library. It was encouraging to see the interest shown as 16 people from the community attended.” Kalaupapa Historical Society Collection, file cabinet 1, drawer 1, box 1, folder 1, item 1, NPS Kalaupapa. At the second meeting of the Kalaupapa Historical Society, the following note was taken: “The second organizational meeting held November 18, 1982, at the Settlement. Twenty-three persons attended, including six people from the National Park Service.”

[72] . “Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa,” 2007, http://

[73] . “To See This Place Stay Sacred,” Ka ‘Ohana O Kalaupapa, Position Paper, 2009, http://

[74] . Elder Orson F. Whitney, Ninety-First Annual Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1921, 32–33.

[75] . Lawrence M. Judd, “To the People of Kalaupapa Settlement,” December 23, 1947, in “Kalaupapa. Res. Supt. Report. October–December 1947,” series M-420, box 15, folder 227, Lawrence M. Judd Collection, Hawai‘i State Archives.

[76] . Ku‘ulei Bell, interview by Fred E. Woods, January 10, 2009, Hale Mōhalu, HI.

[77] . Excerpt from Henry Nālā‘ielua in documentary film The Soul of Kalaupapa: Voices of Exile (2011), directed by Ethan Vincent.

[78] . Philip Schaff, in History of the Christian Church, vol. 7 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916‒23), 650. Schaff explains, “This famous motto . . . is often falsely attributed to St. Augustine . . . but [it is] of much later origin. . . . The authorship has been traced to Rupertus Meldenius, an otherwise unknown divine.” Since October 2005, the author has been sharing the story of Kalaupapa and this message of unity within communities in scores of interfaith venues at universities and ecclesiastical settings.