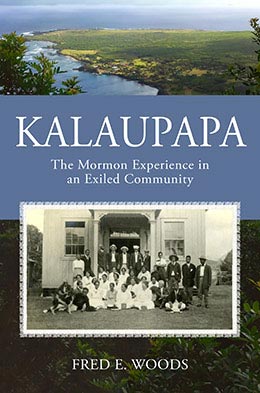

Mormons at Kalaupapa in the Late Nineteenth Century

Fred E. Woods, "Mormons at Kalaupapa in the Late Nineteenth Century," in Kalaupapa: The Mormon Experience in an Exiled Community, Fred E. Woods (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 19-56.

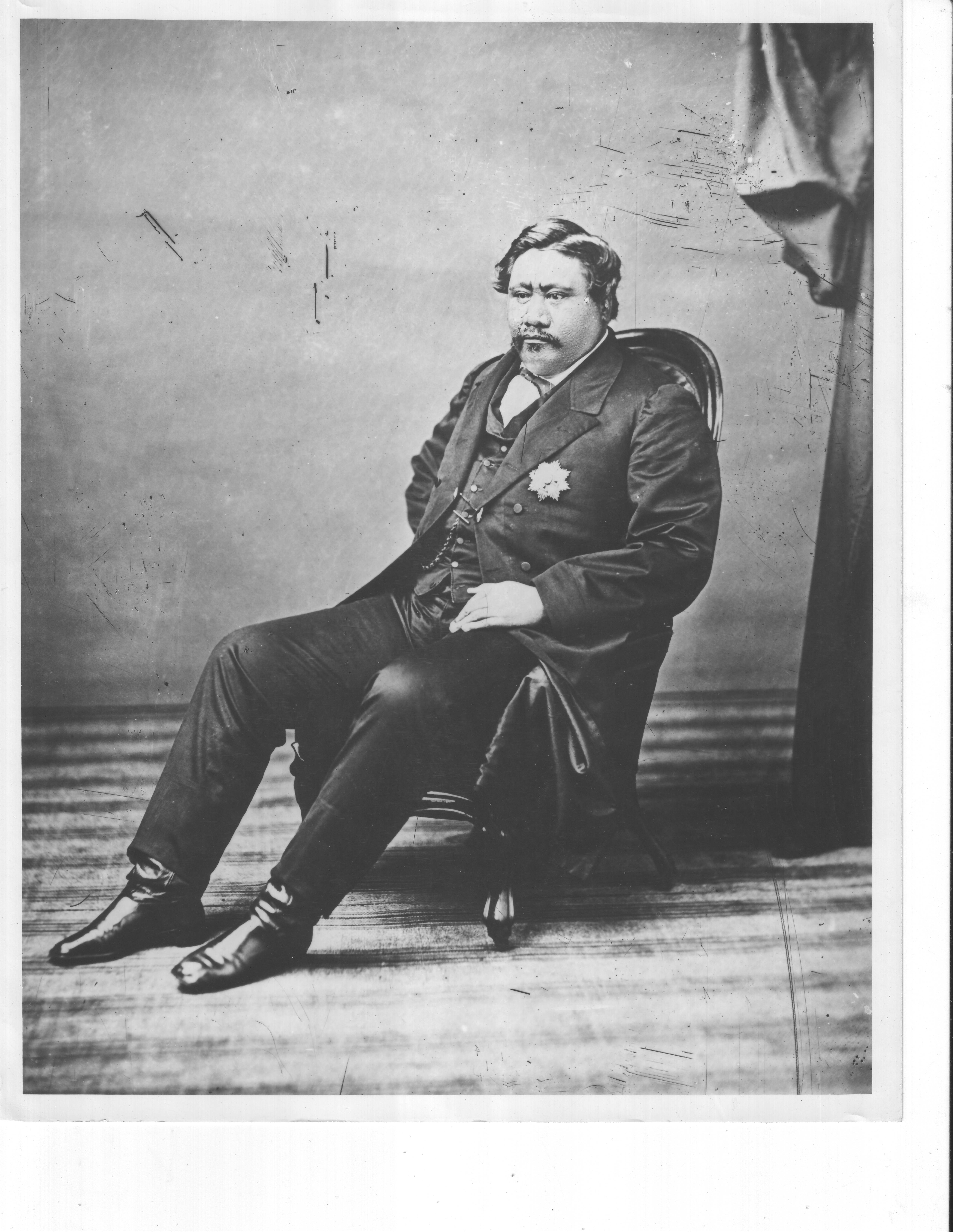

With the population already devastated due to the spreading of infectious diseases, the rapid spread of leprosy, a new disease among Hawaiians, pressed King Kamehameha V to act. The king’s cabinet as well as leading medical authorities counseled him to take swift and drastic measures to ensure the survival of his people.[1] At the same time that Lā‘ie was purchased as a Mormon gathering place on O‘ahu, Kamehameha appointed a separate gathering place for citizens with confirmed cases of Hansen’s disease. This forced segregation prevented Mormons afflicted with the illness from migrating to Lā‘ie.

King Kamehameha V. (Hawai‘i State Archives.)

King Kamehameha V. (Hawai‘i State Archives.)

Kalaupapa Peninsula Chosen

On January 3, 1865, a law passed by the legislature known as “An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy”[2] was also approved by the king. It granted the board of health “authority to enforce the segregation of persons afflicted with the disease, to establish an isolation settlement for confirmed cases and a receiving hospital where suspected cases could be treated and examined and where those having the disease in the early stages could receive treatment.”[3]

Although not a fatal disease, this chronic bacterial illness carried with it a long-held Judeo-Christian stigma: “The historical intertwining of leprosy with religious notions of divine punishment, which gave rise to the corrosive idea that victims of the disease were sinful, shameful, and unclean. The preferred method of dealing with such people was obvious: banishment.”[4] Although this societal view would be embraced by many for centuries, including Westerners who migrated to the Hawaiian Islands, it does not appear to be the customary case among native Hawaiians, who viewed their island people as ‘ohana (family) and viewed them with much aloha (love). The island monarchy, the ali‘i (hereditary Hawaiian ruling class), maintained that the exile of diseased victims was a case of survival because they perceived that this disease threatened the very existence of the Hawaiian kingdom. Yet it could also be persuasively argued that Western physicians leading the board of health and influencing the ali‘i did not have the same degree of aloha that the native Hawaiians had for their suffering people. Historian Kerri Inglis shared her perception that once someone was diagnosed with the disease, all the Western physicians saw was the disease, “whereas the native Hawaiian still saw the person.”[5]

Kalaupapa peninsula from the top of pali. April 2015. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

Kalaupapa peninsula from the top of pali. April 2015. (Photo by Fred E. Woods.)

The isolated settlement selected for the suffering victims was the small, naturally contained Kalaupapa peninsula on the north-central side of the island of Moloka‘i. A description of its geological formation and natural northern setting was published in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser two decades later:

The Island of Molokai is the fifth largest of the Hawaiian Group and contains 200,000 acres. The northerly coast line is very bold, precipitous cliffs or palis coming down to the water’s edge except about midway between the eastern and western points, where an irregular tongue of land projects from the cliffs, enclosing about six thousand acres. There is evidence in the general configuration of this piece of land, and its formation that it is not caused by subsidence, but in fact a later formation, the result of independent volcanic action. The Titanic forces that produced the stupendous palis of the main land had long been extinct before the crater of Kahukoo [Kauhakō] became a vent for the subterranean furnaces, and threw out lava and scoria boulders to form the little peninsula of Kalawao. In short the peninsula or tongue of land is a modern addition to the ancient and grander structure of Nature adjoining, completed when her energies were unimpaired, and before her constructive forces had become paralyzed with incessant use.[6]

When Robert Louis Stevenson visited the settlement in 1889, he was struck by the triangular Pacific peninsula at the foot of the highest sea cliffs on the planet. He described the afflicted, incarcerated people as being surrounded by “a prison fortified by nature.”[7] The patients were initially and aptly referred to as “inmates.” On November 13, 1865, sixty-two people stood bare and alone, each in turn, before a panel of scrutinizing doctors in the Kahili Hospital. The forty-three that were found as leprous were admitted for treatment to be cured or transferred to the isolated leprosy settlement on Moloka‘i. “So began the long and painful history of segregation.”[8]

Conditions at Kalawao in 1866

Nearly a year to the day that the “Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy” was passed, the first dozen “inmates” sadly arrived at Kalawao on January 6, 1866, in the land division on the eastern side of the Kalaupapa peninsula.[9] For over a decade of this forced migration, the peninsula lacked proper facilities. These unfortunate initiates struggled to survive in caves, in grass houses, or under pūhala trees. There wasn’t even a store available for their urgent needs until 1873, and no funding was allocated for the exiled patients’ meager provisions or for frame buildings until 1878.[10]

These inadequate initial conditions at the settlement quickly deteriorated and became horrific as increasing numbers of the ill were dropped off by ship and left to fend for themselves. Inmates were instructed to find their own caretakers from among family or friends to accompany them. Only the destitute were supplied a blanket (two for men) and one set of clothes, which were expected to last the entire year. First, patients were told to find their own food by fishing and by gleaning from the gardens and fields left behind by earlier forced exiles. Residents who couldn’t scavenge enough food were provided with “three pounds of meat and one bundle of pa‘i ‘ai [a byproduct of poi] per week, and nothing else.”[11] No health officials, caregivers, or facilities were furnished to aid the destitute, who were dealing with a multitude of personal emergencies, not the least of which was the emotional pain of relationship separation, community exile, devastating illness, and sudden survival requirements.

However, one bright spot in this otherwise bleak historical account is the support of the native Hawaiians; both those who were on the Kalaupapa peninsula—kama‘āina (native-born people of the land)—prior to the arrival of the patients, as well as kōkua (helpers) who willingly volunteered to assist their dying loved ones. Kerri Inglis explained the attitude of the kama‘āina at the time of arrival of the early patients in contrast to the Western perspective:

From a western perspective . . . it was quite remarkable that the kama‘āina or local residents of that valley and of Kalawao would take in these patients who were the most severe cases. And yet from a native Hawaiian perspective it made total sense. It’s not surprising at all that they would care for these people who had landed on their shores. It was just part of their culture that you welcomed in visitors and even if these people were disfigured or severely ill, that would have made little difference to the native Hawaiians at that time.[12]

Inglis also described the selfless service of kōkua during the latter half of the nineteenth century:

Many of the patients who were sent had others come along with them, which speaks very highly of the native Hawaiian community and culture. That they would go with their loved ones to this very difficult place to care for them because the board of health was not offering this kind of service. The people themselves offered that to their loved ones. And so they had what were known as kōkua, or helpers who came to the settlement and often times these kōkua were spouses, parents, children, even sometimes friends of someone who was declared to have the disease and they would go and they would be their nursemaid. They would cook for them. They would help them with their shelter. And they would stay there with them as long as they could.[13]

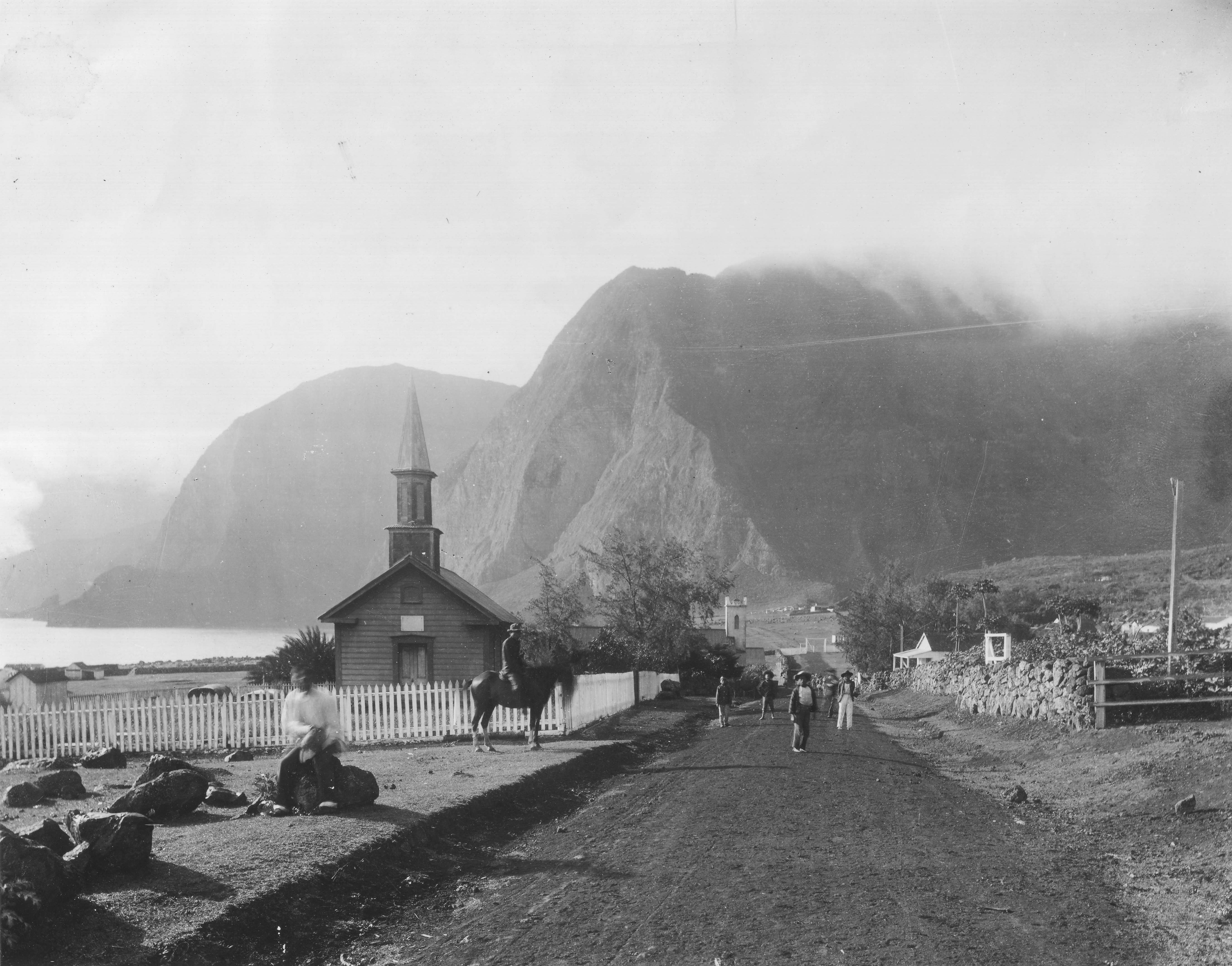

Another positive aspect of this early history is the honored petition of a small minority of thirty-five Christians officially organized into a Protestant congregation just two days before Christmas in the first year of settlement. They built their small church, called Siloama: The Church of the Healing Spring, after the biblical account when Jesus healed a blind man at the pool of Siloam (John 9). This church was dedicated in 1871.[14]

Siloama Church, 1890. (Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives.) Note: If only one image of Siloama is used, this is my preference. Permission granted, no usage fee.

Siloama Church, 1890. (Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives.) Note: If only one image of Siloama is used, this is my preference. Permission granted, no usage fee.

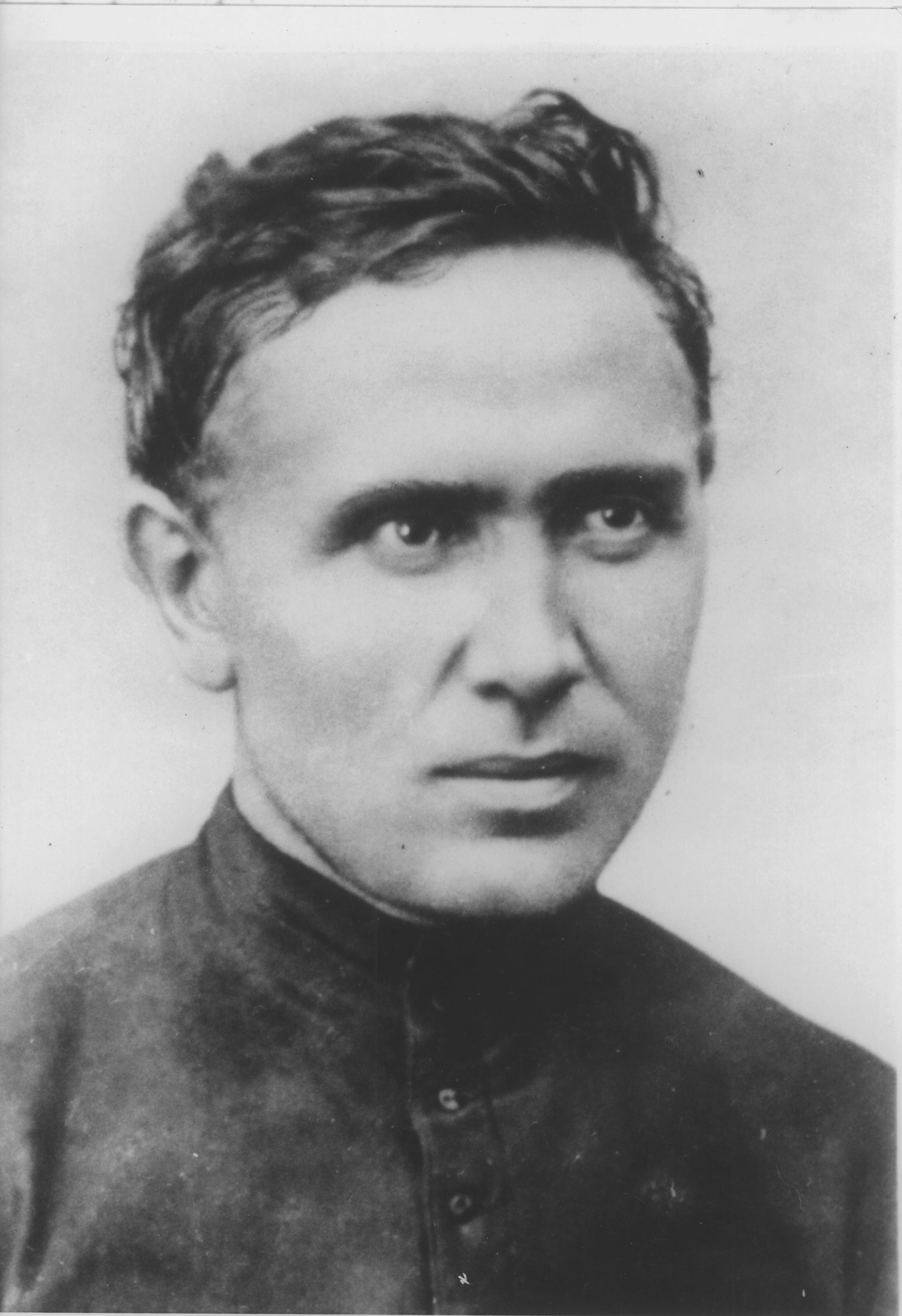

The Arrival of Father Damien

This small Christian band was a minority by the time a determined Catholic priest arrived from Belgium in 1873 to begin his selfless lifelong service among the outcasts. Joseph Damien de Veuster felt like he was called to the ministry despite his parents’ objections. Destiny had intervened when his brother, Pamphile, a priest assigned to serve in Hawaii, contracted typhoid and couldn’t go. Father Damien, not yet ordained, petitioned the superior general in Paris to take his brother’s place and was granted permission. On May 21, 1864, he was ordained to the priesthood in Honolulu and sent to Hawai‘i Island to fulfill his duties. During his nine years on the big island, many of his beloved parishioners were sent to the settlement on Moloka‘i, so when his bishop requested volunteers to go minister and attend to the needs of patients there, Damien jumped at the chance. Although the appointment was supposed to be a rotating assignment among four priests, he left, believing he would never return.[15] He was right.

As the community of desperate residents had rapidly swelled to over eight hundred, a depraved culture of licentious lawlessness proliferated in the peninsula. Writing to the board of health in 1886 about these early years of immorality in the Kalawao settlement, Damien reported conditions he observed: “They passed their time with playing cards, hula, drinking . . . Alcohol. Their clothes in general were far from being clean and Decent. . . . The miserable condition of the settlement at that time gave it the name of a living graveyard.”[16] He continued, “Many an unfortunate woman, had to become a prostitute to obtain friends who would take care of her and children [who] when well and strong were used as servants. . . . Under this pernicious liquor, they would neglect everything except—hula, prostitution and Drinking. As they had no spiritual advisor they would hasten along the road of complete ruin.”[17]

Father Damien began tending the residents on Kalawao when he was thirty-three years old, and by his forty-ninth year the disease had ravaged his body. Perhaps his path was chosen when he took his vow of poverty back in 1860 and chose Damien, the physician of Cilicia, as his patron saint. The namesake Damien spent his life serving others and at last endured a martyr’s death in 1889.[18] Beatified by the Roman Catholic Church in 1995 and canonized in 2009, Father Damien holds international respect and recognition for his life’s devotion of faith and compassionate service.[19] His charity for the outcast and hopeless trumped his fear of contracting the disease. In his own words, “Suppose the disease does get my body, God will give me another one on Resurrection Day.”[20] Bill Malo, a Latter-day Saint and former Kalaupapa resident, explained how the Hawaiians understood this kind of love: “To the Hawaiian people it was always Nui ke aloha ma mua o ka maka‘u—great love over fear.”[21]

Father Damien, age thirty-three (1873). (Courtesy of NPS/

Father Damien, age thirty-three (1873). (Courtesy of NPS/

Cooperation among Different Faiths

Though it appears that Damien, with his high moral decorum, was initially shunned by the masses at the settlement, it was Pastor Heulu and his Protestant deacons of the Church of Siloama who paved the way for Damien and urged their congregation and all patients to accept him.[22] In concert with the Protestant minority, the small Mormon congregation also maintained a high moral ground. The Mormons were led by Jonathan Hawaii Napela, an articulate judge from Maui who had arrived at the settlement as a kōkua to assist his leprous wife, Kiti Keliikuaaina Richardson, shortly before Father Damien arrived. The Napelas and Father Damien would spend the rest of their lives together on this small island peninsula, though Damien would outlive the Napelas by a decade.

Though Jonathan Napela and Father Damien were leaders of different religious denominations, charity knit their hearts as one. Speaking of their close relationship, Ambrose Hutchison, a resident of the Kalaupapa settlement and a contemporary of both Damien and Napela, wrote, “In 1874 the following year after Father Damien arrived in the Leper Settlement and established his home at Kalawao, Mr. J. Napela the then superintendent of the leper settlement, he and Father Damien were the best of friends.”[23]

This would have been an unusual friendship for the time, inasmuch as the Catholics, Protestants, and Mormons throughout the islands were involved with what one historian called “holy war.”[24] During the entire nineteenth century, missionaries from each of these Christian traditions vied zealously for Hawaiian converts. Speaking of this religious conflict, one writer noted, “The various faiths were heated rivals. The moment a missionary departed a village, his sectarian counterpart arrived to dispute everything he had proclaimed.” In 1873, Charles de Varigny wrote that the Hawaiian “believes the Catholic priest when he describes the Protestant minister as a wolf in sheep’s clothing; but he also believes the Protestant minister who speaks of the Catholic priest as an idolator, and of his ritual as tainted with paganism.”[25]

The Mormons were not exempt from this conflict. But Jonathan Napela and Father Damien helped forge a community of unity at the settlement in spite of their theological differences. Disunity was an infectious disease neither faith could afford.[26] Further, there is evidence in the minutes of the Siloama Church that Napela proposed that the Protestants and Mormons join together in raising funds for a shared church building at Kalaupapa. He suggested that each group either meet at different times or in separate parts of the building.[27]

Jonathan Napela, the First LDS Leader at Kalaupapa

Jonathan H. Napela was a bridge builder among the various faiths in the Kalaupapa settlement. He is also considered by Latter-day Saints to be a very influential early Hawaiian convert to Mormonism. Descending from the ali‘i, he was born on September 11, 1813, in Honokōwai on the island of Maui to his father, Hawai‘iwa‘a‘ole, and his mother, Wiwiokalani.[28] In 1831, at the age of eighteen, Jonathan began his formal education on Maui among the first group of forty-three Hawaiian students to attend a Protestant school called Lahainaluna, which the well-known Hawaiian scholar David Malo also attended.[29] From this academic foundation, Jonathan developed a keen mind and went on to practice law. He later served as a district judge in Wailuku between the years 1848 and 1851.[30] Several years earlier, Jonathan married Kiti Keliikuaaina Richardson (half-Hawaiian and half-Caucasian), who was also from ali‘i blood and thus considered a chieftess.[31]

Jonathan Hawai‘i Napela. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Jonathan Hawai‘i Napela. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Jonathan was introduced to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) by Utah missionary George Q. Cannon, who would later serve as a counselor in the Church’s First Presidency.[32] Cannon first came into contact with the influential Hawaiian judge on March 8, 1851. He said Napela was “the most intelligent man I have seen on the Islands.”[33] Concerning their meeting, Cannon noted, “The moment I entered into the house of this native and saw him and his two friends, I felt convinced that I had met the men for whom I had been looking,” meaning someone to assist him with the Lord’s work in Hawaii.[34] Ten months after their first meeting, and after careful investigation by Napela and opposition from the Protestant element on Maui, Cannon recorded that he baptized Napela on January 5, 1852.[35]

During their island years together, Napela and Cannon enjoyed a warm friendship, which Jonathan likewise shared decades later with Father Damien. Less than two weeks after their first meeting, Cannon noted, “I was invited by Napela to come and stay with [him]. I having told [him] I wanted to find somebody to learn me Hawaiian and I would him English; he told [me] he wanted [to learn] & to stay with him.”[36] Not only did they learn each other’s languages, but Napela, while learning the principles of Mormonism from Cannon, was able to share a greater dimension of faith with him and later with the other Utah missionaries.

Napela brought this same faith and determination to Kalaupapa. After his wife, Kiti, contracted leprosy and was forced into exile at the settlement, Jonathan made the decision to remain by her side. He cleverly and immediately secured an appointment as a luna (assistant supervisor) of the settlement at Kalawao, Moloka‘i. However, after only a few months in this capacity, the board of health voted to discharge Jonathan from this position of leadership on October 17, 1873.[37] Evidently, Napela’s charitable heart got the best of him. Their claims against Napela stemmed from his distribution of foods to people beyond the strict list of entitled patients.[38] The Napelas wept together as they read the termination letter instructing Jonathan to leave the settlement.[39]

Adding to his pressure was his recent appointment to serve as the branch president for the Mormon congregation on the Kalaupapa peninsula in early October 1873.[40] In light of insufficient records detailing Mormon history in the years before Napela’s arrival, 1866‒73, we are left to assume that some of the early patients were LDS. Possibly through conversions or new arrivals, a sufficient number of Mormons collected to constitute a congregation for this first Kalaupapa branch. Culling from the journal of John S. Woodbury, Pacific-Mormon historian Riley Moffat observed, “LDS missionaries first proselyted on the [Kalaupapa] peninsula from 1853 to 1856. Their greatest success was at Kalawao. It is doubtful, however, that a branch was functioning when the first patients were brought to the peninsula in 1866. Given the resurgence of missionary work in the late 1860s, it is likely that LDS Hawaiians were among those first patients.”[41]

Jonathan Hawai‘i Napela and another unknown gentleman. (Courtesy of Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii.)

Jonathan Hawai‘i Napela and another unknown gentleman. (Courtesy of Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii.)

Napela’s Petition to Stay

To fulfill his new assignment as spiritual leader for the Mormon congregation and to remain as caretaker for his wife, Jonathan would have to petition for permission to stay at the settlement due to the loss of his position with the board of health. He wrote a passionate letter in his native tongue to E. O. Hall, minister of the interior and chairman of the board of health, and pled with the board to allow him to remain at Kalaupapa, writing, “On August 3, 1843 I took my wife as my legally married wife and on that same day I vowed before God to care for my wife in health and sickness, and until death do us part.” His letter further explained, “I am 60 years old and do not have much longer to live. During the brief time remaining, I want to be with my wife. My wife has also lived a long life, but with this disease, it will quickly shorten her life. Such is the reason for this petition.”[42] Napela’s request was granted, which allowed him to remain at the settlement while serving his wife and the small congregation of faithful LDS Church members.

While serving a mission in Lā‘ie, B. Morris Young wrote a letter on July 6, 1873, to his father, President Brigham Young, explaining Napela’s placement on Moloka‘i and his influence at the settlement:

There are a great many of the Natives dyeing off, of the disese [disease] called Leprosy. I understand that on the Island of Molokai, the place appointed by the board of health, that there are bout one thousand Natives afflicted with that disese, there were quite a large number taken from this Island during the last week. Napela’s wife being afflicted with that disese, he perfered going there than to be saperated from her, concequently the board of halth as appointed him an assistent in the Management of the Lepers, in their settlement on that Island. Although he is thus secluded from the outside world, he still feels an interest in the work of God, and holds meetings, and is preaching to the Lepers. There are quite a number of the members of our Church, afflicted with that dease [disease] now living on Molokai, who are looked after by Napela.[43]

Just three days later, Peter Young Kaeo, an ali‘i who had been exiled to the settlement, explained in a letter to his cousin Queen Emma that Napela and the Saints met for worship services in the Kauhakō Crater. He writes, “The inside of Kauhako Hill . . . is about 80 or 90 ft. high and about the size of Punch Bowl. Inside is hollow—Breadfruit, Ohia, Lehua, Kukui, and other trees grows in it. On the Mauka or Windward side whare the trees grows most thickest Napela holds his Meetings with the Mormons.”[44]

In the spring of 1876, Napela left the settlement temporarily to attend the biannual Latter-day Saint mission conference in Lā‘ie, where he received instruction and reported on his branch members.[45] There is no evidence that Napela attended the Lā‘ie conferences the following year, but a Utah missionary, Simpson Montgomery Molen, visited Napela and the stricken Saints in their remote location. Concerning his visit, Molen wrote, “At this place we found brother Napela, who is taking care of his wife and presiding over the Saints there; he is full of faith, and is still that good-natured, honorable soul.”[46]

Elder Molen makes no mention of the disease taking hold of Napela. Yet less than a year later, another Utah missionary, Henry P. Richards, came to the settlement. He had met with Napela in Salt Lake City nine years previous in 1869 and was shocked at the ravages of illness upon Jonathan. Then forty-seven years old, Elder Richards, who came to the Kalaupapa peninsula during his second mission to Hawai‘i,[47] first arrived at the home of Rudolph Meyer, acting agent for the board of health, to obtain a required license from Meyer so he could proceed down to the settlement. The license was “readily granted.” Richards explained that Meyers included the following instructions in the permit and told of his somber experience:

Henry P. Richards. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Henry P. Richards. (Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Rev Father J. Damien, the Superintendent of the Settlement to shew me the room belonging to the ‘board of health’ as it is not wisdom to sleep in a room where Lepers have lived. . . .

We continued our journey. . . . When we arrived at the summit of the Pali or Mountain—here we were obliged to leave our Horses and descend the Pali on foot, it being a steep rugged descend of several thousand feet before arriving at the plain below, . . . Bro Napela’s house being near the foot of the Pali. . . . .

I called first upon him who was very much pleased to see me but poor fellow I should hardly have recognized him he is so changed since I saw him last in Salt Lake City, his face is swolen—many of his teeth gone—his hands broken out with the disease.[48]

Elder Richards then continued on to Kalawao with his permit, where he met with Father Damien. Richards reported that Father Damien “invited [Richards] to stop with him and partake of his hospitallity, which invitation [Richards] cheerfully accepted.” The two men then spent the evening together in pleasant conversation about the settlement.[49]

Two LDS Congregations on the Peninsula

At this time there were two branches of the LDS Church on the Kalaupapa peninsula—one in Kalawao and the other in Kalaupapa, as Richards’s journal entry the following day attests:

Sun Jan 27th 1878 At 10 A.M. I commenced meetings at Kalawao in a house belonging to Lepo the president of the branch, the house was well filled and quite a number outside, between 40 and 50 present. it was with peculiar feelings that I arose to address a congregation of Lepers, those having the disease in all of its various stage from those who have the disease as yet but slightly, to those who are nearly covered with loathsome sores, too dreadful and sickning to look upon.—after wiping away the tears that came unbidden to my eyes, I addressed the congregation for nearly three quarters of an hour, with much liberty, offering such encouragement to the saints as I was led by the Holy Spirit,—also spoke upon the principles of the Gospel as about half of my congregation were outsiders. I was followed about the same length by Nehemia and Napela. after dismissing the meeting I proceeded at once to Kalaupapa in company with Napela for the purpose of holding afternoon meeting—this place is about two miles distant from Kalawao just across the promontory. Commenced meeting at 2 P.M. the congregation being similar to that of the forenoon meeting in appearance and numbers only a greater proportion were members of the church.—I preached about half an hour and so also did Kalawaia—after which the meeting was resolved into a Conference meeting when the general and local authorities of the church were presented and sustained.—there are 78 members of the church represented in these two branches over which Bro J. H. Napela presides.[50]

Richards then records a delightful scene in which he shared theological views with the dedicated Belgian priest: “After the close of the meeting I returned to my quarters at Father Damien’s and after supper by invitation I took a walk with him to visit the sick. . . . After returning to the house we spent the evening until near twelve oclock discussing Mormonism and Catholicism; however I do not think Either of us was converted over to the other’s religious views.”[51]

The next morning, Damien again invited Richards to visit the sick, but this time Richards was to behold the most extreme cases. After a few visits, Richards informed his guide that he “did not wish to see any more.” He thanked Damien for his “kind hospitality” and “bade him adieu.” Richards further notes, “Father D furnishing me with a Horse to take me to the foot of the Pali—Upon arriving at Napela’s House I found Kalawaia and Nehemia waiting for me. After conversing a short time with Napela and administering to him by his request, I bade him farewell probably never to meet him again in this world with a heavy heart.”[52]

Later that summer, Simpson Montgomery Molen, then president of the Hawaiian Mission, returned and described in detail the somber setting where the Kalaupapa Saints were then meeting:

We held our meetings in a schoolhouse, some 30 or 40 were present, mostly all saints, all lepers except Brother Napela. Their exterior was rather mame and scabby, but for all that their hearts might have been purer and more acceptable than mine. I took the text Heb. Ver., 12:5., whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth—spoke 45min with very good liberty, was followed by elder Gates, Nahemia and Napela. The house would have been full, but it happened to be the day that their rations were being issued consequently many of our folks were absent on that business. There are some 80 or 90 members here, most of whom are lepers, several were not able to get out to meeting. Having a long journey before us, we were obliged to hurry away. We said “Aloha” and dare not shake hands with them.[53]

In a letter dated August 15, 1878, about eight months later, and addressed “To Honorable S. G. Wilder” (minister of the interior for the Kingdom of Hawai‘i), Kiti describes the harsh conditions the Napelas dealt with in the final year of their lives: “The thought has occurred to me to petition you, as you are the provider for these people, and have pity upon my husband and me in this new land by giving my husband, Napela, a job such as a judge for these people.”[54]

Just one year later, the Kalawao Death Register, 1879–1880 notes that Jonathan had died from the effects of this dreaded disease on August 6, 1879. His beloved Kiti died just over two weeks later from the repercussions of the same illness.[55] Less than six months after Jonathan passed away, the comfortable, warm relationship between Father Damien and the Mormons chilled.

The End of Damien’s Entertainment of the Mormons

At the behest of Louis Desire Maigret, Father Damien’s bishop in Honolulu, Damien wrote to the Mormons on February 1, 1880, “Please have the kindness to inform your headman at Lā‘ie [Harvey H. Cluff] that I have received from my bishop a positive prohibition to receive as I am used to do any of your people who in the future may visit the leper Settlement. This my bishop’s order pains my heart very much, Please excuse me—I want to obey orders.”[56]

Drawing of Bishop Louis Desire Maigret from an unknown source. (Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives.)

Drawing of Bishop Louis Desire Maigret from an unknown source. (Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives.)

Although Damien followed this ecclesiastical directive, evidence suggests that his disposition towards members of the Mormon congregation remained kindly. Even up until his untimely death from the effects of leprosy at age forty-nine, he spoke well of them, though he was not fond of their doctrine. Dr. Arthur Mouritz (physician at the settlement between 1884 and 1887) testified that Damien “never spoke disparagingly of them [LDS] . . . and was never bitter to them.” Mouritz also added, “The Mormons only numbered 25 or 30,” which suggests that the LDS congregation was not a serious threat to Damien’s Catholic followers, then numbering over eight hundred.[57] At this time, Catholicism was the predominant denomination on the peninsula.

Catholics and Latter-day Saints

Mother Marianne Cope in her youth (circa 1883). (Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives.)

Mother Marianne Cope in her youth (circa 1883). (Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives.)

There is additional evidence of a continued good relationship between the Catholics and the Latter-day Saints following Damien’s passing, although as one would expect, the Catholics, Protestants, and Mormons held worship services in separate locations. A hint of this relationship is apparent from the life of Mother Marianne Cope, who came to Kalaupapa with several other Franciscan sisters five months before Damien’s passing. Mother Marianne served for three decades at Kalaupapa until her death in 1918. Like Father Damien, she was fully committed to helping the patients in the Kalaupapa settlement. At the time she was invited to serve in the Sandwich Islands Mission, which included Kalaupapa, Mother Marianne wrote confidently, “I am hungry for the work. . . . I am not afraid of any disease, hence it would be my greatest delight to minister to the abandoned lepers.” Five years later, her desires to serve at the settlement were realized.[58]

By the end of the nineteenth century, Mormon elders were permitted to visit Latter-day Saint patients at the Bishop Home for Girls, which housed women of varied faiths (including Mormons), which Mother Marianne supervised.[59] Further, about a week before Mother Marianne’s death, Sister Benedicta volunteered to climb up the steep pali trail from Kalaupapa to topside Moloka‘i in order to get medical help for Mother Marianne. Authors Hanley and Bushnell mention she did not go alone: “Accompanied by George, a healthy kōkua and a Mormon, ‘one of the best men in the settlement,’ she climbed the cliff for the first time in her life.”[60]

LDS Demographics at the End of the Nineteenth Century

It is not known exactly when the first Latter-day Saint chapel was built on the Kalaupapa peninsula, but the Manuscript History of the Hawaiian Mission notes that by the fall of 1884, “It was decided to call upon the Saints in the Maui conference to contribute means towards the erection of a meeting house in the leper settlement.”[61] Two years later, the Daily Bulletin in Honolulu reported, “There are at Kalaupapa, a Protestant, a Roman Catholic, and a Mormon place of worship, at Kalawao a Protestant and a Roman Catholic.”[62] And in 1888, there were LDS meetings being held in both the villages of Kalawao and Kalaupapa.[63] Yet the following year, Robert Louis Stevenson visited the settlement and noted, “The church of the Mormons, exists somewhere in the settlement; but I could never find it.”[64]

In 1895, assistant LDS Church historian Andrew Jenson reported Mormon congregations in both Kalawao (78 members) as well as Kalaupapa (149 members); there were also LDS organizations in both villages: Relief Societies for adult women and Mutual Improvement Associations for young people. Jenson added, “J. B. M. Kapule presides over the Kalawao branch and S. Kekai over the Kalaupapa branch.”[65]

Mouritz’s estimate that there were only about twenty-five to thirty Saints in the settlement a decade earlier suggests a significant growth rate of about ten times the number of Mormons from around 1885 to 1895 in both Kalawao and Kalaupapa. These two Mormon meetinghouses can be confirmed by a map dated to this same year by a local surveyor named Marcus Douglas Monsarrat, who identifies Mormon chapels both in Kalawao, on the makai (ocean side) of the road, and also one in Kalaupapa.[66] It is curious to note that the Protestant, Catholic, and Latter-day Saint places of worship are all located next to each other in Kalawao, which may suggest an early cooperative relationship among these differing faiths.

During the final year of the nineteenth century, the Manuscript History of the Hawaiian Mission notes “a flourishing branch of saints at Kalaupapa.”[67] In this same year, a Mormon missionary named M. Marion Bush also wrote an account of his visit. Like other LDS missionaries who preceded him, the account speaks highly of the Saints, notwithstanding the great obstacles they faced as a result of their sickness:

We had what one might call the painful pleasure of visiting the leper settlement. The Saints here were overjoyed to meet us and nothing was too good for us, regardless of expense. . . . We were allowed to visit all the houses, and were permitted to see many terrible and pitiful sights. Some had no eyes; indeed, no face at all; some with no hands, others with no feet, and others with neither hands nor feet. Yet the Saints here are as prompt about their duties as anywhere on the islands. They are regular in their attendance at Church, pay their tithing and are good Christians. Some poor fellows actually crawl on “all fours” to the meeting house, and most any Sunday one could see there a poor fellow with no hands leading another with no eyes to the place of worship.[68]

Such visits made by Bush and other LDS missionaries certainly lifted the morale of the local Church members, and as they parted ways, missionaries like Richards, Bush, and others were certainly inspired by the Kalaupapa Saints, who proved faithful in spite of their trials.

Music Among the Patients

By the end of the nineteenth century, uplifting music, together with ecclesiastical visits, sacred places of worship, and inspirational leadership, helped to edify and unite the community. Documents and photographs reveal an abundance of music on the Kalaupapa peninsula, bringing relief and happiness to suffering patients in the settlement. For example, when Professor Benjamin Sharp passed through the settlement to collect archaeological and zoological specimens in the early fall of 1893, he noted, “I saw crowds of Lepers waiting near the landing place, . . . and a band struck up a merry tune which was followed by ‘Marching thru Georgia.’ These men were once in the Hawaiian band [and] got Leprosy & were sent here to end out their days.”[69]

Kalawao Band, 1900. (Courtesy of NPS/

Kalawao Band, 1900. (Courtesy of NPS/

Music was also supported by Mother Marianne Cope, who emerged as a very influential leader when Father Damien passed away in 1889. She was instrumental in acquiring a piano for the girls at the Bishop Home, where, as noted previously, females from different Christian denominations lodged. In a newspaper article from the Honolulu-based Independent about a decade after her arrival, Mother Marianne reported to the editor, “Our girls are very happy and as gay as butterflies, they consider themselves lucky girls to have such a fine piano for their use. . . . There is nothing in the world that makes them so happy as music does; they seem to forget all their troubles.”[70]

As the nineteenth century came to a close, music continued to ring through the settlement and also reached the ears and hearts of those who visited there. Such was the case when three vessels full of members of the Hawai‘i Board of Health and their guests arrived at the Kalaupapa landing during the summer of 1899. In an article titled, “Thou Shalt Relieve Him, Leviticus xxv:35,” the Hawaiian Star reported from Honolulu that when these visitors neared shore, they heard the “excellent” music of a Kalaupapa band made up of eight musicians playing “Aloha ‘Oe,” which “came well to the boats and ship.” It was a greeting appreciated by all, rather than a “mass meeting of residents to state grievances,” as previously experienced. “The leaders of the colony said they had absolutely no kicks to make.”

Female musicians at Bishop Home, early twentieth century. (Courtesy of NPS/

Female musicians at Bishop Home, early twentieth century. (Courtesy of NPS/

After the inspection, the board of health determined that the patients were satisfied. Upon the departure of the board, and a year after Hawai‘i had been annexed and was now a US territory, “almost the whole settlement . . . congregated to say good-bye. The band played until the steamer sailed, the last strains to come over the water being Star Spangled Banner and Aloha Oe,” an apt melody from a people who were, on the surface, amalgamated as both Hawaiians and American citizens.[71]

Bishop Home Girls’ Choir, ca. late nineteenth century. Damien Center Archive, Belgium.

Bishop Home Girls’ Choir, ca. late nineteenth century. Damien Center Archive, Belgium.

Notes

[1] Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, vol. 2, 1854–1874: Twenty Critical Years (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1953), 73. Kuykendall notes, “It is not known when or how leprosy was brought to Hawaii. The Hawaiians applied several names to it; the most common one, Mai Pake (Chinese disease), had reference to the fact that the disease was common in China; it is believed that it was brought from that country to the islands, but there is no definite proof that such was the case. Leprosy was in the kingdom at least from the reign of Kamehameha III [1825–1854], but the earliest official mention of it was in the last year of Kamehameha IV [1863].”

[2] To view the entire document, see appendix B, “An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy.”

[3] Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, 2:73.

[4] Tayman, The Colony, 3. It can be argued that the word leprosy as mentioned in the Bible (Leviticus chapters 13–14) could be applied to a variety of skin diseases rather than just as what is now referred to as Hansen’s disease. Concerning these two chapters, see Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society, TANAKH Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 234. This book notes that these two chapters are one unit, “prescribing the elimination of the impurity caused by tzara‘at. This has sometimes been translated as ‘leprosy’ (or ‘leprous affection’), but the disease today called leprosy (Hanson’s [sic] disease) was not known in biblical times and the description given in the Bible is not consistent with it.” However, the long-held stigma of leprosy as a form of divine judgment stems from the retribution Miriam received as a punishment for raising her voice against her brother Moses (Numbers 12) as well as King Uzziah, who was also smitten when he dared to burn incense on the altar of Jerusalem’s temple, a sacred rite only authorized to be performed by select priests (2 Chronicles 26). Saul Nathaniel Brody, The Disease of the Soul: Leprosy in Medieval Literature (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974). In his preface, Brody argues, “Of all the diseases that afflicted medieval man, leprosy especially came to be understood as divine punishment for sinfulness and to be viewed as no other sickness known to man has ever been. . . . Sin and disease were associated from earliest times, and by the Middle Ages the connection had become traditional.” Kerri A. Inglis, Ma‘i Lepera: A History of Leprosy in Nineteenth-Century Hawai‘i (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2014), 40. Inglis asserts, “The stigma leprosy derived from the Western/

[5] Kerri Inglis, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, June 29, 2007, Hilo, HI. She also added, “I think one thing we have to understand is the historical stigma that comes with leprosy. It’s based largely on a Judeo-Christian stigma . . . that equated those with this particular disease as being immoral or unclean. And while native Hawaiians did not accept that in the beginning we certainly find that by the end of the 1800s native Hawaiians are speaking in those terms as well. And so there seems to be a cultural shift, if you will, in that perception of this particular disease.” See also Inglis, Ma’i Lepera, 86. Here, Inglis further explains, “The Hawaiian culture did not attach a stigma to leprosy until their perspective was influenced by the Western way of thinking about and dealing with the disease.”

[6] Robert J. Creighton, “Molokai: Description of the Leper Colony on this Island,” Pacific Commercial Advertiser, November 1885, 2.

[7] Robert Louis Stevenson, Travels in Hawaii, ed. A. Grove Day (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1973), 48.

[8] Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom, 2:74.

[9] Greene, Exile in Paradise, 51. Greene’s manuscript is considered to be the definitive work on the settlement. Herein she notes that “contrary to popular myth, it is doubtful that any of the exiles were forced to jump into the surf and swim to shore as a matter of regular procedure.”

[10] Cecilia Carter and Cecil Killehua, “Kalaupapa Settlement,” Kalaupapa History and Description, series M-420, folder 211, Lawrence M. Judd Collection, Hawai‘i State Archives. Further, “Kalaupapa in Brief,” dated April 23, 1948, notes, “Living conditions in the early days were bad. At first the government expected the patients to be colonists, growing their own food. This failed, and it was necessary to send supplies; but for many years food was often inadequate; shelters were poor and insanitary; medical care was spasmodic, and water had to be carried, often a mile or more, from a tiny stream.” Kalaupapa History and Description, series M-420, folder 211, Lawrence M. Judd Collection, Hawai‘i State Archives. For more information regarding the early days of how patients were treated at Kalaupapa, see Kerri A. Inglis, Ma‘i Lepera: Disease and Displacement in Nineteenth-Century Hawai‘i (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press: 2013).

[11] Greene, Exile in Paradise, 53.

[12] Kerri Inglis, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, June 29, 2007, Hilo, HI.

[13] Kerri Inglis, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, June 29, 2007, Hilo, HI.

[14] Greene, Exile in Paradise, 55–56. Ethel Damon, Siloama: The Church of the Healing Spring (Honolulu: Hawaiian Board of Missions, 1948), 10. Damon notes, “As to the founding of this little Church of the Healing Spring, all was done regularly according to the true Democratic and Congregational pattern. Among patients sent to Kalawao during the first year, beginning in January of 1866, were thirty-five members of Congregational Protestant churches on all the islands. In June of 1866 at the Aha, or Annual meeting of Congregational church in Honolulu, these thirty-five ‘were released to form a church by themselves at Kalawao.’ In October of the same year elders of the Maui and Molokai Presbytery, meeting at Wailuku, Maui, in the Kaahumanu Church, sanctioned this new church body and elected Mr. Forbes [Reverend Anderson O. Forbes] its regular pastor. On the 23rd of December following, as soon as Pastor Forbes and his Hawaiian associate, the Reverend S. W. Nueku, could make the journey over the trail to Kalawao, the organization of the church took place.”

[15] Greene, Exile in Paradise, 81–83.

[16] Report of Father Damien, March 1, 1886, Board of Health, Hansen’s Disease, Series 334, Box 34, Folders 1–3, Hawai‘i State Archives, Honolulu. The official count of patients when Damien arrived in Kalaupapa on May 10, 1873, was 816, and in 1886, when Damien gave this report, the number had peaked to 1,175. See Kalaupapa History and Description, M-420, 211, 1887–1968, Lawrence M. Judd Collection, Hawai‘i State Archives.

[17] Report of Father Damien, March 1, 1886, Hansen’s Disease, Series 334, Box 34, Folders 1–3, Hawai‘i State Archives, Honolulu. When a committee was appointed to reinvestigate the situation of the settlement and made a visit just four and a half months later, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, in an article titled “Hawaiian Parliament,” printed this report to the Hawaiian Parliament from the “Molokai Committee,” as it was called, which showed the improvements that had been made since the first patients were brought to Kalawao two decades earlier: “Your committee landed at Kalaupapa at 7 a.m. Saturday, July 17th, and were warmly welcomed by the Rev. Father Damien, the Catholic priest and introduced to a large number of the lepers there. Your committee was very favorably impressed with the beautiful appearance of the place, Kalaupapa, Kalawao and Waikolu being fine lands, facing the north and surrounded by a pali behind. These fine lands were selected by Kamehameha V, the strong-minded King, to be the home of all those who were so unfortunate to be lepers. Here they were to rest their bodies forever. It is with great pleasure that your committee mention[ed] the comfortable, neat and clean dwelling houses for the lepers, . . . together with different houses of worship, hospitals, store houses and the residence of the doctor. Your committee found that there was a good reservoir built . . . from which the water was conducted in a pipe, a distance of some two miles to Kalawao. . . . Your committee found the lepers in very comfortable circumstances. . . . Their houses are comfortable, and kept very neat and clean, and many were surrounded by beautiful gardens. Their clothing was clean, and of good quality.” Though the community at large was a part of the improvements, it seems quite apparent that Father Damien’s influence was a vital factor. For the full article, see “Hawaiian Parliament,” The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, October 9, 1886, 3.

[18] Greene, Exile in Paradise, 80.

[19] Damien was officially beatified on June 4, 1995, in Brussels, Belgium. He was later canonized and declared a Saint in the Roman Catholic Church on October 11, 2009, in Rome. For an excellent, readable biography of Father Damien’s life, see Gavan Daws, Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1973).

[20] Vital Jourdan, The Heart of Father Damien (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing, 1955), 168.

[21] Anwei Skinsnes Law, Kalaupapa: A Collective Memory (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2012), 21. This is similar to the scriptural passage, “There is no fear in love; but perfect love casteth out fear” (1 John 4:18).

[22] Damon, Siloama, 18.

[23] Ambrose Hutchison, “In Memory of Reverend Father Damien J. De Veuster and Other Priests Who Have Labored in the Leper Settlement of Kalawao, Moloka‘i” (original manuscript housed at the Damian Centre in Leuven, Belgium), 19. Hutchison was a resident of the settlement between 1879 and 1932. Further, in discussing the close friendship of Father Damien and Jonathan Napela, Most Reverend Larry Silva, Bishop of Honolulu, noted, “Even now I think there is a good ecumenical spirit in Kalaupapa. Whenever one of the churches has a celebration the other patients, who even though they may not share the faith in its fullness with whoever is having the celebration, will join in as one family, so I think there is a practical sort of accumulation that has lived out there.” Bishop Larry Silva, interview by Ethan Vincent, assisted by Fred E. Woods, August 6, 2008, Honolulu.

[24] M. Guy Bishop, “Waging Holy War: Mormon-Congregationalist Conflict in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Hawaii,” Journal of Mormon History 17 (1991): 113. This source sheds light on the heated conflict between the Mormons and Protestants during this time, as Bishop explains, “A better understanding of how the Protestants and the Mormons viewed one another emerges from the dialogue provided by the LDS journal accounts and the Protestant station reports of this period, written annually to the American Board in Boston.”

[25] Charles de Varigan, Fourteen Years in the Sandwich Islands, 1855–1868, trans. and eds. Alfons L. Korn (Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1981), 149.

[26] Dr. Arthur Mouritz, physician at the settlement between 1884 and 1887 and during the last decade of Damien’s life, solemnly testified when witnesses were being gathered for the consideration of Damien’s canonization, “Father Damien despised the Mormons because of their false belief and their duping of the people—and rightly so. He never spoke disparagingly of them however and was never bitter to them.” Testimony of Arthur Mouritz, 1938 Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archbishop’s Archive in Mechelen), Belgium, 84. Additional evidence suggests that although Damien did not agree with LDS theology, he had a good relationship with Napela, other LDS missionaries who visited the settlement, and the Mormons at Kalawao and Kalaupapa. Mouritz later authored two books dealing with leprosy: The Path of the Destroyer: A History of Leprosy in the Hawaiian Islands and Thirty Years Research into the Means by Which It Has Been Spread. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Ltd., 1916; A Brief World History of Leprosy. Honolulu: A. Mouritz, 1943.

[27] Law, Kalaupapa, 83. The minutes of the Siloama Church housed at the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library in Honolulu note that Napela made this suggestion in October 1876, but that his recommendation was not agreed to.

[28] See International Genealogical Index, File 1235151 and the Genealogy of Hattie Panana Kaiwaokalani Napela, typescript, Bishop Museum, Honolulu. This was taken from the Honolulu Advertiser, July 19, 1901. An obituary for Jonathan’s father in a local Hawaiian newspaper notes he was an active deacon in the Protestant Church on Maui: “Another pillar of the church has fallen here in Wailuku, his name is Hawaii. . . . Hawaii was an old man, but physically nimble and strong. . . . He was 70 or more years old and was born here on Maui at Kaanapali. He lived long in ignorance but upon Mr. Richards arrival here in Lahaina, soon turned to godliness.” See “The Death of Hawaii, a Deacon at Wailuku,” Ka Nonanona 3, no. 22 (March 19, 1844), 118–20. The author wishes to thank Hawaiian translator Jason Achiu for providing this translation.

[29] Scott G. Kenney, “Mormons and the Smallpox Epidemic of 1853,” Hawaiian Journal of History 31 (1997): 18. Kenney is correct on this point of education, but he is incorrect on the date of Jonathan’s birth and thus on the date he began school at Lahaina Luna. Primary documents covering the Lahaina Luna classes may be obtained at the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library in Honolulu, hereafter cited as HMCS.

[30] Document from the Judiciary History Center, Honolulu. Appreciation is expressed to Chris Mahelona (a Napela descendant) for providing the author with a copy of this document.

[31] Alfons L. Korn, ed., News from Molokai: Letters between Peter Kaeo & Queen Emma, 1873–1876 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1976), 16, footnote 8. The title “Chieftess” is used here. See also Napela, Letter to E. O. Hall, President of the Board of Health, 1873 Board of Health Records, Letters Incoming, Series 334, box 5, folder 4, Hawai‘i State Archives, Honolulu. Here, the date of Napela’s marriage to Kiti is evidence, wherein Napela explains, “On August 3, 1843, I took my wife as my legally married wife.” From them sprang one known child, Hattie Panana Kaiwaokalani Napela. See International Genealogical Index, File 1235151. Further, the names of Napela’s wife and daughter, written, “Kitty [Kiti] Kelii-Kuaaina Richardson” and “Hattie Panana Kaiwaokalani Napela,” are consistent with the original source documents. Decades later, the Deseret Evening News, May 4, 1885, cited from MHHM, mentioned Napela’s daughter, who had visited Utah: “A company of prominent visitors from Hawaii spent the day in Salt Lake City Utah. . . . One of the party, Mr. Samuel Parker, has been representing the Sandwich Islands at the New Orleans Exposition. His wife, who is also of the party, is a daughter of J. H. Napela, a prominent Hawaiian, who spent several months in our city a number of years ago, and was one of the first converts to the Gospel on the Sandwich Islands.”

[32] Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:42. Jenson indicates that Cannon later served as first counselor in the First Presidency to Presidents John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Lorenzo Snow.

[33] George Q. Cannon, journal, March 8, 1851, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as Church History Library); The Journals of George Q. Cannon: Hawaiian Mission, 1850–1854, ed. Chad M. Orton vol. 2 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, forthcoming).

[34] George Q. Cannon, My First Mission (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1879), 27.

[35] George Q. Cannon, journal, January 5, 1852, Church History Library. Cannon’s complete journal during his years as a missionary in Hawaii, coupled with comprehensive annotations (including an abundance of references to Napela), is available in The Journals of George Q. Cannon: Hawaiian Mission, 1850–1854, ed. Adrian W. Cannon, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Chad M. Orton (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014).

[36] George Q. Cannon, journal, March 21, 1851, Church History Library.

[37] Napela wrote a series of letters to the Hawai‘i Board of Health commencing on April 29, 1873, in his capacity as a luna. These letters confirm that he was very literate, having received a good education at Lahaina Luna and serving as a judge in Maui. These five letters, written by Napela to Edwin O. Hall, president of the board of health, are dated April 29, May 1, May 5, May 6, and July 24, 1873. There are also two letters by Napela to S. [Samuel] G. Wilder, a member of the Privy Council, dated May 10 and May 19, 1873. All seven of these letters are available in Hawaiian with English translations in the following collection: Board of Health Incoming Letters, 1873 April–July, Series 334, Hawai‘i State Archives, Honolulu. The author thanks Jason Achiu, Hawai‘i State Archivist, for his translations of these letters.

[38] Board of Health Minutes, October 17, 1873, Office of the Interior, series 259, vol. 2, 84, A. L. Korn, News from Molokai, 140. Here, Korn notes that Napela was discharged for “allowing food rations to be issued to persons not on the official lists of lepers.”

[39] “Letter dated October 23, 1873,” in Korn, News from Molokai, 139.

[40] “General Conference in the Sandwich Islands,” Deseret Evening News, February 13, 1874. This article notes, “A Semi-annual General Conference of the Sandwich Islands Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was held at Lā‘ie, Oahu, Hawaiian Islands, Oct. 6, 7, and 8, 1873. . . . Napela presides at the Kalaupapa, Island of Malokai [sic].” There were 749 total patients in the settlement in 1873. It is not known what percentage were LDS. See Inglis, Ma’i Lepera, 74 for stats of patients during the 19th century in general.

[41] Riley Moffat, “Church on the Peninsula,” unpublished article presented to the Mormon Pacific Historical Society at Kalaupapa, April 27, 2007. The author expresses gratitude to Moffat for sending him this piece via email on January 4, 2015.

[42] J. H. Napela, Series 334: Board of Health 1873, Letters Incoming, Hawai‘i State Archives.

[43] B. Morris letter to Brigham Young, July 6, 1873, Brigham Young Incoming Correspondence, 1839‒1877, box 33, folder 38, CR 1234/

[44] “Letter of Peter Kaeo to Queen Emma, July 9, 1873,” in Korn, News from Molokai, 18. There are scores of references to the Napelas in these letters, with additional comments by Korn. These letters indicate that Kaeo had a very active and personal relationship with the Napelas. See pages xx, 14, 16 fn. 8, 20, 22–24, 33–36, 42, 44–45, 48, 52–54, 55 fn. 6, 57, 64–67, 71–72, 74, 76‒79, 80–82, 107, 112, 113 fn. 12, 114–15, 117, 122–24, 126, 129, 130–31, 139, 140 fn. 1, 141, 146, 149–50, 152–53, 157 fn. 4, 173, 182–86, 195, 199–200, 208, 217, 220–21, 227–28, 230, 233, 235‒37, 239, 240, 243–49, 251, 253, 255, 258, 270–71, 274, 319.

[45] Letter of Alma L. Smith to Brigham Young, April 25, 1876, in “Conference—Distribution of Elders—Baptisms, etc.,” Deseret News, May 24, 1876, 266.

[46] S. [Simpson] M. [Montgomery] Molen, Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, November 12, 1877, 750. In the journal of Simpson Montgomery Molen, an entry for the date of May 8, 1877, states, “We rode to Kalaupapa where we found Bro. Napela and wife, she being a leper he came here to be company for her in her imprisonment.”

[47] Henry P. Richards, journal, January 26, 1878, Church History Library. During this second mission (1876‒79), Richards presented Queen Kapiolani with a stylish bound copy of the Book of Mormon in Hawaiian. He also secured for LDS missionaries tax exempt status during their ministry as well as license to perform marriages, available to those belonging to other religious denominations. See D. Michael Quinn, “They Served: The Richards Legacy in the Church,” Ensign, January 1980, 24–29.

[48] Henry P. Richards, journal, January 26, 1878. Napela had visited Salt Lake City eight years earlier and met with Church President Brigham Young. While there, he also received his temple blessings and learned much about the Church in Utah and of the temporal affairs of the territory. Following this trip, he traveled to Hawai‘i. Soon after his ship made port at Honolulu, he went to visit King Kamehameha V and reported in detail his Utah experience on November 20, 1869. Napela later wrote to Brigham Young, telling him of his visit with Kamehameha. See Fred E. Woods, “An Islander’s View of a Desert Kingdom: Jonathan Napela Recounts his 1869 Visit to Salt Lake City,” BYU Studies 45, no. 1 (2006): 23–34. Napela’s visit also encouraged other Hawaiian Saints to immigrate to Utah to receive their temple blessings. By 1890, a settlement of Hawaiian Saints was established southwest of Salt Lake City, called Iosepa; over two hundred Mormons eventually gathered there. When the Lā‘ie Hawaii Temple was announced in 1915, they returned to their island homes, where they could not only enjoy the temple blessings but also their own native environment. See Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lā‘ie (Lā‘ie, HI: The Jonathan Napela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, BYU–Hawaii, 2011), 48–50. For more extensive information on Iosepa, see Dennis H. Atkin, “Iosepa, A Utah Home for the Polynesians,” in Voyages of Faith: Explorations in Mormon Pacific History, ed. Grant Underwood (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 71‒88; Tracey E. Panek, “Life at Iosepa, Utah’s Polynesian Colony,” in Proclamation to the People: Nineteenth-Century Mormonism and the Pacific Basin Frontier, ed. Laurie Maffly-Kipp and Reid L. Neilson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2008), 170‒81; Matthew Kester, Remembering Iosepa (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[49] Henry P. Richards, journal, January 26, 1878, Church History Library.

[50] Henry P. Richards, journal, January 27, 1878, Church History Library. The fact that Napela presided over two branches meant that he was no longer just a president of one branch, but rather the district president of both. In 1878 there was a total of 802 patients in the settlement, which means that 9.7 percent of them were LDS. See Inglis, Ma’i Lepera, 74.

[51] Henry P. Richards, journal, January 27, 1878, Church History Library. Writing to the editor of the Salt Lake Herald a dozen years later about his visit with Father Damien, Richards said, “I found him to be a gentleman in every sense of the word, kind and affable, not a sentence uttered to cause the least degree of bad feeling.” See “The Leper Settlement,” Salt Lake Herald, February 9, 1890.

[52] Henry P. Richards, journal, January 28, 1878, Church History Library.

[53] MHHM, July 31, 1878. In this reference, the person named is simply Elder Montgomery. However, there was never an LDS missionary who served in Hawai‘i during the nineteenth century by this name. Rather, the person referred to is Elder Simpson Montgomery Molen. Further, the comment by Molen that all but Napela had leprosy is difficult to reconcile, due to the journal entry Richards had made six months earlier. In this same year, the biannual LDS mission conference held in Lā‘ie reported that between the conferences held in April 1878 and October 1878, nineteen leprous patients had joined the LDS faith. See MHHM, October 6, 1878.

[54] Kiti Napela, Letter to Honorable S. G. Wilder, August 15, 1878, Board of Health Incoming Letters, series 260, Hawai‘i State Archives, Honolulu. Although Hansen’s disease made living conditions difficult for Jonathan and Kiti, their housing was apparently quite pleasant compared to the living conditions of other patients. This may be evidenced from a letter written from Kalawao by N. B. Emerson to S. G. Wilder, shortly after the death of the Napelas. In this letter, Emerson writes, “There are several houses in the Settlement which in my opinion, it would be expedient and wise for the Board to buy. First the house in which Napela lived. You are more or less acquainted with the size and accommodations offered by this house. But let me remind you that the main body of it is 22 X 20 ft. and it has a veranda of 5 ft. 9 ins in front. This part was built in 1873 and is of tongue & grooved N.W. and ceiled within with the same. This part has 4 rooms not far from equal in size. The roof of this will before long need reshingling. The rear of this is an addition of two rooms one 8 X 10 ft. used as a wood shed and another 9 X 12 ft. This is in pretty good repair and is built like the first part. Attached to the South side of this is also an L or el which measures 10 X 22 ft. with a veranda of 3 ½ ft. in front. This has been recently built. Mr. Sumner, who with John Kaahai [illegible word follows] is the executor of Napela’s estate here, proposes to sell this house exclusive of this southern el to the Board for $200. I have told him the Board would probably buy the whole house el and all, and have made him an offer $235, subject to your approval. It would probably cost the Board twice this sum or perhaps more to build a house with as much accommodation as this.” N. B. Emerson, Letter to S. G. Wilder, October 21, 1879, 2–3, Board of Health Incoming Letters, series 334, Box 8, 1879, Hawai‘i State Archives.

[55] Kalawao Death Register, 1879–1880, Hawai‘i State Archives, indicates that Kiti Richardson Napela died on August 23, 1879.

[56] Letter of Father Damien to Mormon leader at Lā‘ie (on the island of O‘ahu), February 1, 1880, Damian Centre, Leuven, Belgium. For a biographical sketch of Bishop Maigret, see Robert Schoofs, Pioneers of the Faith: History of the Catholic Mission in Hawaii, 1827‒1940 (Honolulu: Louis Boeynaems, 1978), 23. The author expresses appreciation to Stuart Ching, archivist at the Sacred Hearts Archive in Honolulu, for sharing this information with him. A Mormon missionary named Carl Anderson, who visited Kalaupapa soon after Damien’s letter was written, stated, “We had been informed by the missionaries who had been here a few months before us, that they had been entertained by a Catholic priest, and the idea suggested itself to us to go and try him. We met him at the store and accordingly, Br. W. E. Alexander, my companion, asked him if he could inform us where lodgings might be obtained. In reply to this he told us to follow him to his home, which we did. On arriving at his house he invited us to supper, and then we were shown our place of rest. The following morning we found on the table, in the adjoining room, a letter addressed to the Mormon Elders, from our hospitable friend, stating that he had received positive orders not to receive any of our people who in the future might visit the place, and that while these, his bishop’s orders, pained his heart very much, he was obliged to obey them. . . . We held our meetings and were very much pleased with the spirit that prevailed. The saints in this place are very humble, and look forward to a time when sickness and disease shall have no more power over them.” See Carl Anderson, “Sandwich Islands Leper Settlement,” in Contributor, May 1880, 174–75.

[57] “Testimony of Arthur Mouritz, 1938,” 84, Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archbishop’s Archive in Mechelen), Belgium.

[58] Letter written from the St. Anthony Convent in Syracuse, New York, on July 12, 1883, by Mother Marianne Cope to Reverend Leonor Fouesnel, in the author’s possession. Thanks to Sister Mary Laurence Hanley for providing a copy of this letter, which is also included on the page preceding the table of contents in a book she coauthored: Sister Mary Laurence Hanley, O.S.F., and O. A. Bushnell, Pilgrimage and Exile: Mother Marianne of Molokai (University of Hawai‘i Press, 1991). For a later printing of this exhaustive treatment of Mother Marianne, see Sister Mary Laurence Hanley, O.S.F., and O. A. Bushnell, Pilgrimage & Exile: Mother Marianne of Molokai (Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 2009). Mother Marianne Cope was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in 2005; seven years later, at the time of canonization (October 21, 2012), he also declared her a saint. See “St. Marianne Cope,” Catholic Online, http://

[59] Hanley and Bushnell, Pilgrimage & Exile, 354. Herein the authors note that Protestant pastors were also permitted to visit patients belonging to their faith. Entries in Mother Marianne’s journal for the dates of May 30, June 17, July 8, July 15, July 22, August 12, 1900, and January 20, 1901, note visits by Mormon elders to see LDS Church members at the Bishop Home. The author expresses gratitude to Sister Mary Laurence Hanley, who provided a typescript copy of these journal entries, which is now in possession of the author.

[60] Hanley and Bushnell, Pilgrimage & Exile, 381.

[61] MHHM, October 2, 1884.

[62] “Among the Lepers,” Daily Bulletin, July 19, 1886, 2. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, http://

[63] MHHM, July 31, 1888. This source culls from the journal of the LDS missionary Fred Beesley and notes, “Elders Fred Beesley and Enoch Farr jun. and some native brethren (Kaleohano, Koses and one other) sailed from Honolulu per steamer “Moku” for the island of Molokai, . . . on August 10th, [they] started for the leper settlements Kalawao and Kalaupapa, arriving there on the 10th. On Sunday, August 13th, they had a meeting in both places. At Kalaupapa they set Momo[na] apart to preside over the branch, to succeed the former president who was released because of being sick and feeble. They also set apart Kekai and Kipa as counselors to President Momona. On the 13th the Elders visited the grave of N[a]pela, near the crater; it was covered with lime mortar.”

[64] Stevenson, Travels in Hawaii, 51.

[65] Andrew Jenson, Letter to the Editor, “Jenson’s Travel,” Deseret News, September 10, 1895. Further, the MHHM, October 8, 1899, notes that by the close of the year, Edwin W. Fifield, secretary for the LDS Hawaii mission, reported, “At Kalaupapa, Molokai, the leper settlement, there is a flourishing branch of Saints, and preparations are now being made to build a comfortable meeting house at that place, most of the means already being raised.” See Elder Edwin W. Fifield, Letter to the Editor of the LDS periodical, October 12, 1899, Lā‘ie, Hawai‘i, published in the Deseret Evening News, November 11, 1899. At this time (1895), there were a total of 1,087 patients in the entire settlement which means that the total of LDS patients (227) made up nearly 21 percent of the patient population. See Inglis, Ma’i Lepera, 74.

[66] Emmett Cahill, Yesterday at Kalaupapa (Honolulu: Editions Limited, 1990), 44.

[67] Edwin W. Fifield, “The Hawaiian Mission,” Report to the Deseret News, MHHM, October 8, 1899.

[68] Elder M. Marion Bush visited the settlement sometime between April and October 1899. He reported his experience to the editor of the Deseret News, and it was published under the heading “The Missionary Fields in Hawaii,” February 15, 1900. See MHHM, February 15, 1900.

[69] Benjamin Sharp Jr., journal, September 11, 1893, Benjamin Sharp Jr. Papers, Box 1, Folder 51, University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. The author extends gratitude to Joseph-James Ahern, who kindly sent a scanned copy of this document to the author via email on January 7, 2016. For biographical information on Sharp, see “Benjamin Sharp Jr. Papers, 1877–1916,” Online Collection Guides, University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center, http://

[70] Mother Marianne, “They Forget Their Troubles,” Independent, December 14, 1898, 1.

[71] “Thou Shalt Relieve Him,” Hawaiian Star, July 31, 1899, cover page. To access this article, see Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, http://