Introduction

Why This Story Matters

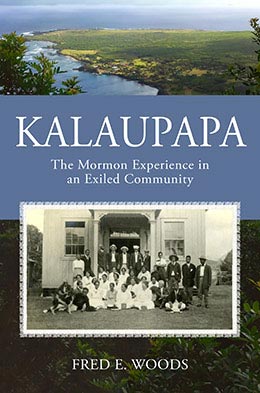

Fred E. Woods, "Introduction," in Kalaupapa: The Mormon Experience in an Exiled Community, Fred E. Woods (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), xi-xviii.

Why This Story Matters

This book tells the riveting story of a unique settlement on the Hawaiian island of Moloka‘i known as Kalaupapa.[1] Here, patients afflicted with leprosy (now known as Hansen’s disease) were forced to separate from society; yet, working together, they forged a loving, united community from which sacred space emerged.

In 1969, the same year that Neil Armstrong took a giant step onto the moon, the Hawai‘i Board of Health finally made the move to permanently end the isolation of all patients—but many chose to remain. This book helps explain why they wanted to stay and emphasizes the Mormon experience encountered on that hallowed ground.

In 1980, the US Department of the Interior and National Park Service established the Kalaupapa National Historic Park to preserve the historic buildings and heritage of this unique community. One of the stipulations for creation of the park was that patients would be able to live at Kalaupapa as long as they wanted and that their lifestyle and privacy would be protected. The year 2016 marked the sesquicentennial of the moment when the first dozen “inmates” were outcast to this island prison. It is time to tell the remarkable story of transformation and metamorphosis of this settlement, and I am honored to share it.

I felt the tug of Kalaupapa long before I ever visited there. My wife, JoAnna, and I had been researching the Hawaiian Islands in preparation for a research and anniversary trip to O‘ahu in 2003. I asked her where she would like to visit after my research was completed. “I don’t care whatever else we do, but we must visit the leprosy settlement on Moloka‘i,” she said. As is our pattern, her impression set me on a decade-long passion and changed our lives forever.

It was high adventure getting to that remote peninsula. The destination necessitated a precarious mule ride down the highest sea cliffs in the world.[2] At last we heard the thunderous pounding of the Pacific reverberating against the northern coastline, and we inhaled deeply at our safe arrival. Our small caravan spilled us out onto the flat four-mile terra firma peninsula that I would one day consider consecrated.

Prior to our visit, we had arranged to meet with Ku‘ulei Bell, the postmaster of Kalaupapa and the woman who knew everyone and everyone’s business. From that initial experience, my world was turned upside down. My reaction was much like the Mormon Apostle Elder Matthew Cowley’s after his first visit to Kalaupapa:

I went there apprehending that I would be depressed. I left knowing that I had been exalted. I had expected that my heart, which is not too strong, would be torn with sympathy, but I went away feeling that it had been healed. . . . I [left] . . . appreciating my friends, loving my enemies, worshiping God, and with a heart purged of all pettiness. This is a transformation for me, and for it, I am indebted to the . . . Saints of Kalaupapa.”[3]

I too left feeling like I was the one in need. Their story, those people, that community—they cannot be restrained from lifting outsiders. It was a mystery longing to be uncovered. The surf and the winds beckoned me to tell it.

Scope of Documentary Efforts

Over the years, the phrase “Saints of Kalaupapa” has come to have a broader meaning for me, reaching beyond my view of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) at the settlement. I have often thought about the community as a whole and the general composition of its inner goodness. Among other things, I have learned that the literal translation of Kalaupapa may be rendered “flat plain” or “flat leaf.”[4] In either case, I discovered through much reading, many interviews, and multiple firsthand encounters that Kalaupapa is a leveling experience: one crosses the boundaries of one’s own professed beliefs and ethnicity into a larger realm of brotherhood and compassion. For it is in Kalaupapa where religious denominations and cultural divides dissolve—where the love of God and humankind manifest themselves in a truly magnificent way.

In 2011, I coproduced a documentary with LDS filmmaker Ethan Vincent, titled The Soul of Kalaupapa: Voices of Exile, a film which compliments my book.[5] This documentary is based on extensive research as well as dozens of interviews. One of the interviewees was Pat Boland, who has guided thousands of visitors on tours of the settlement over several decades. Pat noted, “There used to be a priest that would come [to Kalaupapa] to serve part-time from England when the regular priest was on vacation. He told me that the two holiest places in the world, as far as he was concerned, were Jerusalem and Kalaupapa.”[6] Having spent much time at both of these locations, I might have said the same thing.

After over a decade of research, interviews, expeditions, and contemplation, I believe I’ve unearthed the settlement’s secrets. It is the story of community—community unlike anywhere else in the world—not a space divided by borders and barriers or fences and enclosures, but a place which beckons every race and religion, every color and creed. Kalaupapa is proof that community is possible, though not without price. The cost was suffering—suffering together. Their shared suffering was the mortar for their community—their pain, the bonds for their friendships.

This book reveals how people in exile, united in malady, forged relationships greater than nuclear family ties, dissolved social constructs of prejudice and intolerance, and melded into a community of brotherhood, charity, and happiness. The unveiling of this community focuses on Mormon history, but the story is universal with no partiality toward any particular race or religion. Therefore, this book is written for both academics and a general audience with an emphasis on the Mormon experience. It also represents a deliberate blend of scholarly analysis coupled with highlights from oral history interviews, thus providing a solid historical base with a penetrating touch by eyewitnesses, making this work both personal and powerful.

This book reveals the impact the Kalaupapa community had on Mormon patients who lived at or visited the settlement and reveals that their experiences were quite similar to others who had any contact with this unique peninsula of sacred space, regardless of race or religion. There have been many books written on Kalaupapa by a variety of authors as noted in my bibliography. However, what makes this book unique is that it is the first book ever written that emphasizes the Mormon experience at Kalaupapa whose LDS members made up an average of about 10–20 percent of the total population of the patients during the time it was an active settlement. It also depicts how this sacred space touched people who came into contact with this extraordinary terrain.

Methodology

I have taken a chronological approach throughout this work. I set the stage by first discussing the encounters Captain James Cook experienced as he reached the Hawaiian Islands, followed by the launching of Mormonism in Hawai‘i prior to Latter-day Saints afflicted by the disease first being sent to Kalaupapa.

Each chapter follows chronologically, highlighting the Mormon experience in the settlement and how the LDS patients were an inclusive part of the community and not withdrawn from their loving neighbors. There are several sections that capture the visits made by loving Saints in different eras, ministering encouragement and service to their stricken brothers and sisters. As a result, such visits, mostly from Utah missionaries called to the Hawaiian Mission and fellow members serving nearby on the topside of Moloka‘i, were life changing and left such visitors who ministered wanting to be more kind and loving.

Throughout this work I have relied heavily on primary historical sources in order for the reader to capture the authentic, historical voice of the past and, above all, the divine touch of Kalaupapa. To ensure that this touch is experienced, this book includes excerpts from scores of interviews to capture the message that people from all walks of life were deeply moved by the Kalaupapa experience either as patients in the settlement or those who have visited this sacred turf. These powerful interviews will be available in a forthcoming book by the author titled Reflections of Kalaupapa.

Themes of Charity, Service, and Community

The charity and uncommon service rendered at Kalaupapa is relevant in any age and serves as a reminder of the importance of erecting bridges instead of barriers, finding common ground instead of battleground, and in valuing one another regardless of ethnicity and religiosity. To me, it provides a vivid illustration of the need for Latter-day Saints and others to not only join hands but to look outside the circle of their faith’s community and to embrace the universal message to love one another, regardless of their differences. Such an ecumenical philosophy of inclusiveness seems to be desperately needed in a world that suffers from societal diseases such as selfishness, pride, bigotry, and prejudice. In addition, it is hoped that the message of the Kalaupapa community will serve as a reminder of the acute need for each of us to generate light instead of heat and to apply the Latin maxim: “In the essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; and in all things, charity.”[7]

Notes

[1] Kerri A. Inglis, Ma‘i Lepera: Disease and Displacement in Nineteenth-Century Hawai‘i (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press: 2013), xiii. In her dissertation, Inglis uses the strict definition of Makanalua for the peninsula of the north shore of Moloka‘i generally. However, I prefer to use the more commonly known name of Kalaupapa to refer to the entire peninsula, although the traditional name is technically correct in referring to whole peninsula of Makanalua, which is made up of three districts (ahupua‘a) of Kalawao to the east, Makanalua in the middle, and Kalaupapa to the west.

[2] . These cliffs are nearly two thousand feet tall.

[3] . Henry A. Smith, Matthew Cowley: Man of Faith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954), 300–301.

[4] Emmett Cahill, Yesterday at Kalaupapa (Honolulu: Editions Limited, 1990), 2.

[5] . Fred Woods and Ethan Vincent, The Soul of Kalaupapa: Voices of Exile, Documentary, Provo, UT: BYUtv, 2011. This documentary can be accessed at this URL: http://

[6] . Pat Boland, interview by Ethan Vincent and Fred E. Woods, May 2007, Kaneohe, HI.

[7] Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, 8 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916–23), 6:650. Schaff explains, “This famous motto . . . is often falsely attributed to St. Augustine . . . but is of much later origin. . . . The authorship has recently been traced to Rupertus Meldenius, an otherwise unknown divine.”