Close Friends as Witnesses: Joseph Smith and the Joseph Knight Families

William G. Hartley

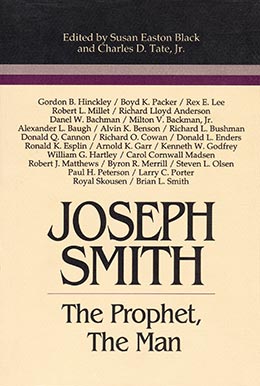

William G. Hartley, “Close Friends as Witnesses: Joseph Smith and the Joseph Knight Families,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, the Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 271–83.

William G. Hartley was associate research professor at the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History at Brigham Young University when this was published.

On a winter day in January 1842, Joseph Smith became reflective. He decided to list in the Book of the Law of the Lord the names of those “faithful few” followers who had stood by him since the beginnings of his ministry—“pure and holy friends, who are faithful, just, and true, and whose hearts fail not” (History of the Church, 5:107; hereafter HC). Among these faithful few were:

my aged and beloved brother, Joseph Knight, Sen., who was among the number of the first to administer to my necessities, while I was laboring in the commencement of the bringing forth of the work of the Lord. . . . For fifteen years he has been faithful and true, and even-handed and exemplary, and virtuous and kind, never deviating to the right hand or to the left. Behold he is a righteous man, may God Almighty lengthen out the old man’s days . . . and it shall be said of him, by the sons of Zion, while there is one of them remaining, that this was a faithful man in Israel; therefore his name shall never be forgotten. (HC 5:124-25)

The prophet also recorded the names of two of Joseph Knight’s sons, Newel and Joseph Knight, Jr., in the same book “with unspeakable delight, for they are my friends” (Ibid).

At that time, Joseph Smith had known the Knights for almost 16 years, since 1836, when the Knights hired him to work on their New York property. This contact came after Joseph’s First Vision but before he had received the gold plates. Joseph was trusted and his message believed within the extensive Knight family network. Some 12 family units eventually accepted his prophetic calling and the restored gospel which he proclaimed. After the Smiths, the Joseph Sr. and Polly Peck Knight family could be considered the Second Family of the Restoration. The Knights knew Joseph Smith and accepted his claims before Oliver Cowdery, Martin Harris, or David Whitmer. These Knights stood by Joseph more steadfastly than some in the Prophet’s own family. The Knights’ lives and statements serve as a special type of witness—a family witness—of Joseph Smith’s divine calling, which those investigating Joseph Smith’s claims should weigh carefully (see Hartley).

Joseph’s friendship with the Knights began when he was 20 years old and single. In late 1826, he became a hired hand for the Knights and others in the Colesville, New York, area (near present Binghamton)- 115 miles southeast of Palmyra by dirt road. Young Joseph worked on their farm and probably helped at their sawmill. He bunked with Joseph Knight Jr., who said that in November of 1826 Joseph Smith “made known us that he had seen a vision, that a personage had appeared to him, and told him where there was a gold book of ancient date buried, and that if he would follow the direction of the angel, he could get it. We were told this in secret.” [1] Another son, Newel, said Joseph Smith visited them often and “we were very deeply impressed with the truthfulness of his statements concerning the Plates of the Book of Mormon which had been shown him by an Angel of the Lord.” (qtd. In Hartley 19).

It was Father Knight who assisted Joseph’s courtship of Emma a SmithHale: “I paid him the money and furnished him with a horse and Cutter [sled] to go and see his girl” (Jessee 32). Joseph and Emma were married on 18 January 1827 and moved to the Smith home near Palmyra.

When the time came for Joseph Smith to obtain the plates, Father Knight was visiting at the Smith home, and Joseph used the Knight wagon when he retrieved the plates. Returning home, he told Father Knight, regarding the plates, that “it is ten times Better than I expected.” Joseph described the plates but, said Father Knight, “seamed to think more of the glasses or urim and thummem th[a]n he Did of the Plates. For says he, ‘I can see any thing. they are Marvelus’” (Jessee 33).

By early 1828 Joseph and Emma had moved to the Hales’ property in Harmony, Pennsylvania, about 30 miles from the Knights. When Joseph found it impossible to earn a living and translate the plates at the same time, he and Emma asked Father Knight for help. Although the Knights were themselves “not in easy circumstances” Father Knight gave Joseph provisions and “some few things out of the Store, a pair of shoes, and three Dollars.” A few days later, Father Knight visited the Smiths and gave Joseph some more money “to buoy [buy] paper to translate” (Jessee 36). Joseph Knight, Jr., recalled that “Father and I often went to see him and carry him something to live upon” prior to Oliver Cowdery’s arrival (qtd. In Hartley 214).

Mrs. Polly Knight was not yet a believer, so in March, 1828, Father Knight took her by sled to visit the Smiths: “Joseph talked with us about his translating and some revelations he had Received and from that time my wife Began to Beleve” (Jessee 36).

In early 1828, when Oliver Cowdery became Joseph’s scribe, they visited Father Knight, seeking provisions. Father Knight said he bought and delivered to them “a Barral of Mackrel and some lined paper for writing,” and about ten bushels of grain and six of potatoes and a pound of tea. Joseph and Oliver rejoiced at the food and paper and “then they went to work and had provisions enough to Last till the translation was Done” (Jessee 36). Joseph Smith later praised Father Knight for these items “enabled us to continue the work when otherwise we must have relinquished it for a season” (HC 1:47). Clearly, the Knight family helped the world receive the Book of Mormon sooner than would have happened otherwise. Some of the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon is written on paper the Knights gave Joseph.

In May 1829, Father Knight desired to know what he should do regarding the divine work then unfolding. The prophet inquired of the Lord and received a revelation instructing Father Knight to “seek to bring forth and establish the cause of Zion” and to give heed to God’s word “with your might” (D&C 12:6). This was the first of many revelations now in the Doctrine and Covenants that were directed at the Knights (see D&C 12, 23, 37, 52, 54, 56-58, 72, 124).

In early June, 1829, Newel Knight drove Joseph and Oliver to Fayette, New York, to the Whitmer home, where the two men finished the translating work. The Three Witnesses and then the Eight Witnesses were allowed to see the plates, but none of these special witnesses were Knights, since they lived quite a distance away.

On the day the Church was organized, a third of the 60 people attending were Knight relatives from Colesville. Of the baptismal service that followed the meeting, Father Knight said, “I had some thots to go forrod [forward]. But I had not re[a]d the Book of Morman and I wanted to oxeman [examine] a little more.” Later he felt that “I should a felt Better if I had gone forward” (Jessee 37).

Joseph Smith, knowing the Knights were ready to join the Church, went to Colesville to preach. His challenge to Newel Knight to pray vocally led to Newel’s being attacked by an evil spirit which lifted him from the floor “and tossed [him] about most fearfully” (HC 1:82). Neighbors gathered and saw Joseph Smith cast the devil out by the authority of Jesus Christ. Newel felt sudden relief, and Joseph considered this dramatic exercise of priesthood power to be the first miracle performed in the Restored Church (see HC 1:83-84). Newel accepted baptism, becoming the first of more than 60 of the Knight clan who joined the Church.

At the Church’s first conference, held at the Whitmers’ house on 9 June 1830, those attending experienced spiritual outpourings resembling the Day of Pentecost. Newel Knight beheld a marvelous vision much like the one Stephen the Martyr saw:

I saw the heavens opened, I beheld the Lord Jesus Christ seated at the right hand of the Majesty on High, and it was made plain to my understanding that the time would come when I would be admitted into His presence, to enjoy His society for ever and ever. (HC 1:85)

Despite local opposition, many Knight relatives were baptized on 28 June 1830. These included their son Joseph Jr., daughter Esther and her husband William Stringham, and daughter Polly. Mother Polly Knight’s maiden name was Peck, and among her Peck relatives baptized with her were her brother Hezekiah and his wife Martha, and her sister Esther and husband Aaron Culver. Newel Knight’s wife Sally was also baptized, as was the prophet’s wife Emma (see HC 1:87-88).

Angry neighbors prevented these newly baptized souls from being confirmed, and a constable arrested Joseph Smith, the first of two such arrests (see HC 1:88-96). An angry Father Knight hired two of his neighbors well-versed in the law, James Davidson and John Reid, to defend Joseph Smith, and he was acquitted at midnight. But resentments in the area became so heated, Joseph Knight, Jr., said that, “that night our wagons were turned over and wood piled on them, and some sunk in the water, rails were piled against our doors, and chains sunk in the stream and a great deal of mischief done” (qtd. in Hartley 215).

Joseph Smith was quickly arrested a second time and tried in Colesville. Father Knight’s lawyer friends felt too fatigued to help, but his pleadings won them over. Mr. Reid noted that Joseph Knight, Sr., was “like the old patriarchs that followed the ark of God to the city of David.” Newel, when called to testify, told the court that no, Joseph Smith had not cast a devil out of him, but Joseph—by God’s power—had done so. Father Knight’s attorneys again prevailed, and Joseph Smith was freed.

At Harmony, Pennsylvania, in early August 1830, Newel and Sally and Joseph and Emma, along with John Whitmer, decided to have a sacrament and confirmation service. Joseph, on his way to obtain wine, was stopped by a heavenly messenger and commanded not to purchase wine from nonbelievers (see D&C 27). So the five made their own juice, partook of the sacrament, and Emma and Sally were confirmed.

In September, 1830, Newel and his sister Anna’s husband, Freeborn DeMille, attended the Church’s second conference, also held at Fayette, New York (see HC 1:108-20). There Newel became the young prophet’s confidant during a surprise crisis caused when Hyrum Page claimed to have received revelations for the Church through a peep stone. Hyrum carried “quite a roll of papers full of these revelation,” Newel said, which led many astray. Newel said that Joseph Smith “was perplexed and scarcely knew how to meet this new exigency.” Sharing the same room, the Prophet and Newel spent “the greater part” of that night “in prayer and supplication” (13). In response, Joseph received a revelation (D&C 28) that spelled out proper channels for revelation to reach the Church. Brother Page was corrected and peace restored. At that conference Newel was ordained a priest and Freeborn DeMille was baptized.

After this conference, Hyrum Smith was made president of the Colesville Branch. He and Jerusha moved in with Newel and Sally Knight, and the two couples became good friends. Newel Knight soon replaced Hyrum as president of the Colesville Branch, whose membership was almost totally Knight relatives. In 1831, this branch of Knights showed remarkable trust in Joseph Smith by obeying a revelation he received calling them to “assemble together at Ohio” (D&C 37:3). The Knights “were obliged to make great sacrifices of our property,” according to Newel. He sold 60 acres of land, Freeborn DeMill 61 acres, and Aaron Culver 100 acres. Joseph Knight, Sr., sold 140 acres, “two Dwelling Houses, a good barn, and a fine orchard” (Knight 19). Sixty-two Knight kin moved to Ohio to help initiate this “first gathering of Zion” in this dispensation. The cluster included Joseph and Polly Knight and every one of their seven children. Other relatives in this migration included Pecks, Slades, DeMilles, and Stringhams.

This Knight/

The Knights helped to establish this center for the gathering of Israel (D&C 57). In an impressive ceremony, 12 men representing the twelve tribes of Israel laid the first log as a foundation of Zion; five of the men were Knight relations. Newel was one of the seven men who dedicated the Independence temple site. Such rituals seemed full of promise to all the Knights except mother Polly, who was dying. She became the first Latter-day Saint buried in Zion. Death claimed two more Knights that year, including Newel’s sister Esther.

In this outpost colony of the Church, the families labored hard during an optimistic first year of building, fencing, and establishing homes. Once again, they agreed to consecrate properties in order to live cooperatively. When a council of high priests was created to govern the Missouri church, Newel Knight became one of them, and also he continued to be president of what was still termed the Colesville Branch. As part of plans to one day build the Independence temple, six Knight men made labor pledges.

Joseph Knight, Sr., decided to remarry and chose Phoebe Crosby Peck, who was Polly’s widowed sister-in-law. Phoebe had four children of her own, and she bore Father Knight two more. Counting Phoebe’s four, Joseph Knight, Sr., was father or stepfather of 13 children.

In 1834, Missourians drove the Saints, including the Knight network, from Jackson County. The mobbers shot Philo Dibble, whom Newel Knight saved from death through a remarkable priesthood blessing (see Christensen 79). Fearing for their lives, the Knights rushed to the Missouri River ferries. Joseph Knight, Jr., told of women and children walking with bare feet on frozen ground (see Hartley 216). The Knight group lost much property, including a gristmill. The family had moved twice before, but this was their first forced move. Of that hard winter, Emily Colburn Slade Austin recalled: “We lived in tents until winter set in, and did our cooking out in the wind and storms” (Austin 72).

Lacking proper food and shelter, many Saints became victims of “fever and ague”—probably malaria—including Sally Knight. After she gave birth to a son who died, she died. “Truly she has died a martyr to the gospel,” her bereaved husband Newel eulogized (46).

Newel, being a high councilman, was sent to Kirtland to help build that temple and to receive temple blessings. At Kirtland he boarded with his good friends Hyrum and Jerusha Smith. There he met and fell in love with another boarder, Lydia Bailey, whose belief in Joseph Smith and experience with the miraculous was equal to his. Her husband had deserted her, and both of her children had died, so her family sent her to Canada for a change of scenery. In late 1833, while lodging with the Nickerson family, she heard Joseph Smith preach and saw his face “become white and a shining glow seemed to beam from every feature” (Homespun 18). This witness of the spirit converted her. She moved to Kirtland, where she met Newel Knight, and on 24 November 1835, was married to him in the Hyrum Smith home by Joseph Smith. Theirs was the first marriage performed by priesthood authority in this dispensation, which pleased Joseph Smith greatly (HC 2:320).

Newel took Lydia back to Missouri just in time to join the Saints’ exodus from Clay County. They settled around Far West in Caldwell County. When Joseph Smith moved to Far West in early 1838, Newel rejoiced to be near his friend and to hear him preach again because “his words were meat and drink for us” (61). Knight relatives in Far West were saddened to see several leading elders forsake the church. Newel’s high council had to cut off the entire Missouri stake presidency, including David and John Whitmer, two of the Book of Mormon witnesses. Oliver Cowdery also veered away (see Cannon and Cook). Missourians and Saints again clashed, so once more in wintertime the Knights and other Saints surrendered homes and lands to become destitute refugees in 1838-39. With extreme hardship the Knight clan struggled across Missouri eastward to Illinois.

Camping where Nauvoo would rise, the Knights had passed through the “refiner’s fire” in Missouri, the first of three difficult tests of their loyalties. Unlike the Three Witnesses and other giants of the early days of the Restoration, they had not buckled their knees in Missouri. The Knight families did not doubt their religious convictions despite suffering losses they estimated at $16,000, which today would be more than $500,000 (see Mormon Redress Petitions). Once again they moved, and their presence in Nauvoo in 1839 bears witness of their confidence in the Prophet Joseph. Since joining the Church nine years before, they had moved to four different settlements because of their convictions; Nauvoo made five. It is interesting to note that between 1831 and 1846 the Knights helped to pioneer no less than ten LDS settlements: near Painsville in Ohio; Kaw Township, Clay County, and Far West in Missouri; Nauvoo in Illinois; Mt. Pisgah, Garden Grove, and Council Bluffs, in Iowa; and Winter Quarters in the Nebraska Territory.

At Nauvoo the Knight clan included at least 11 family units—four headed by members of Father Knight’s generation, and seven by adults of Newel and Lydia’s generation. When Joseph Smith reached Nauvoo from Missouri imprisonments, Newel rejoiced:

As soon as I could I went to see him, but I can never describe my feelings on meeting with him, and shaking hands with one whom I had so long and so dearly loved, his worth and his sufferings filled my heart with mingled emotions while I beheld him and reflected upon the past, and yet saw him standing before me, in the full dignity of his holy calling, I could but raise my heart in silent but ardent prayer that he and his family and his aged parents may never be torn apart in like manner again. (86)

The Knights helped build Nauvoo. Newel served on the high council. He and Joseph Knight, Jr., built several gristmills. One day Joseph Smith spied aged Father Knight hobbling down a Nauvoo street. Quickly overtaking his longtime friend from New York, the Prophet handed the old man a cane and insisted he take it and then that he pass the cane down through the Knight family to descendents named Joseph (Hartley 3). About this time, the city council gave Father Knight a lot and built him a house (HC 4:76; Hartley 3, 142-43). Knight Street then, as now, memorializes the Prophet’s esteem for the Knight family.

In Nauvoo, the Knight group faced and passed a second great test of faith. When the Prophet introduced several higher doctrines, including temple ceremonies and plural marriage, some Saints disaffected, but the Knight cluster did not (Lyon 70). They helped construct the temple, performed baptisms for the dead, and by early 1846 more than 20 adults in the Knight group had received their temple endowments and sealings. Four of Joseph Sr. and Polly Knight’s children entered into plural marriage.

When Joseph and Hyrum Smith were killed, few mourned their deaths more than Newel Knight, whose heart broke. He vented his sorrows in his journal:

O how I loved those men, and rejoiced under their teachings! It seems as if all is gone, and as if my very heart strings will break, and were it not for my beloved wife and dear children I feel as if I have nothing to live for. . . . I pray God my Father that I may be reconciled unto my lot, and live, and die a faithful follower of the teachings of our Murdered Prophet and Patriarch. (170; emphasis in original)

After the martyrdom, the Knights passed a third severe test of their religious loyalty. Unlike some others, they did not forsake the faith and follow pseudo-successors. Of Father Knight’s 13 children and stepchildren, all who were in Nauvoo as adults (except perhaps Nahum for whom we lack records) followed Brigham Young west, or spouses did in the case where the mate had died.

When packed up and ready to leave Nauvoo, Newel “had the satisfaction of walking once more through the streets of the city of Joseph, and of beholding once again the noble works, whose foundations had been laid by our beloved Prophet before his martyrdom” (197). After crossing the Mississippi River, Newel looked back a last time at the city and felt great anguish:

My heart swelled, . . . from the eminence where I stood, I saw the noble works of Joseph the Prophet and Seer, and of Hyrum the patriarch, with both of whom I had been acquainted from their boyhood and knew their worth and mourned their loss. (198)

During the westward exodus of the Saints, Newel died of exposure in northern Nebraska in January, 1847. Joseph Knight, Sr., died at Mt. Pisgah in Iowa a month later. The Knight families, from the Church’s second year when Polly Knight died, to its fourteenth when Newel and his father died, sacrificed some of their best blood for the gospel’s sake.

Although none of the Knights were privileged to be witnesses of the Book of Mormon plates, their labors helped launch the Restoration, and through their devotion to Joseph Smith, they serve today as a solid and sizeable family witness of the Prophet. They are not silent witnesses. Lydia wrote her life story. Newel kept an invaluable journal. Joseph Knight, Sr., penned his recollections as did Joseph Jr. These four records contain personal histories, but they also stand as four written witnesses of Joseph Smith. All four of the Knight authors knew and revered the Prophet.

The Knight families knew Joseph in his early adult days, back when he was accused of digging for gold and using peep stones. Such criticisms did not make them doubt his calling. If the Prophet had been a charlatan or not genuinely religious as detractors then and since have charged, the large Knight clan would have known it and not followed him so faithfully for so long. Their devotion to the Prophet Joseph Smith was based on knowing him well, and it bears witness that his character, from age 20 to his death at 38, was righteous and good. His critics have questioned his motives, truthfulness, and divine claims; his friends have provided several evidences to demonstrate that God used him to restore truth to the earth. Such debates and discussions, when marshalling “evidence,” should not ignore the Knight family as long-term witnesses of the Prophet Joseph Smith. They had been loyal to the Prophet longer than anyone except the Smiths, and they felt Joseph was what he claimed to be.

The cane which Joseph Smith gave Joseph Knight, Sr., in Nauvoo continues to pass down the generations of Knights from one descendant named Joseph to another. This cane is tangible memorial of the friendship and mutual religious faith Joseph Smith and the Joseph Knight, Sr., families shared.

Bibliography

Austin, Emily M. Mormonism; or Life Among the Mormons. Madison, WI: Cantwell, 1882.

Cannon, Donald Q. and Lyndon W. Cook, eds. Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830-1844. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983.

Christensen, Clare B. Before and After Mt. Pisgah. Salt Lake City: privately printed, 1979.

Hartley, William G. “They Are My Friends”: A History of the Joseph Knight Family, 1825-1850. Provo, UT: Grandin, 1986.

History of the Church. 7 vols. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980.

Homespun [Susa Young Gates], ed. Lydia Knight’s History. Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1883.

Jessee, Dean C. “Joseph Knight’s Recollection of Early Mormon History.” BYU Studies (Aut 1976) 17:29-39.

Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833-1838 Missouri Conflict. Ed. and comp. Clark V. Johnson. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1992.

Knight, Joseph, Jr. “Incidents of History.” LDS Church Archives.

Knight, Newel K. Journal. Version C. In possession of author.

Lyon, T. Edgar. “Historical Highlights of the Saints in Illinois.” First Annual CES Religious Educators Symposium (19, 20 Aug 1977) 1:69-71.

Notes

[1] This and all subsequent statements in this article that are quoted from Joseph Knight, Jr., unless otherwise noted, are from his “Incidents of History,” LDS Church Archives.