Writing about the Prophet Joseph Smith

Dallin H. Oaks

Dallin H. Oaks, “Writing about the Prophet Joseph Smith,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 3‒20.

President Dallin H. Oaks is the First Counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

This address was given 13 March 2020 at the Brigham Young University Church History Symposium in the Church Office Building Auditorium in Salt Lake City.

I am pleased to be part of this important symposium sponsored by BYU and the Church History Department. My participation is a review of some of my personal conclusions and experiences, guided by vital inspiration, in writing about the Prophet Joseph Smith in various capacities for more than fifty years. I will present no additional research or even new insights from the treasury of The Joseph Smith Papers. I will reference three articles in professional journals, a book, and a published speech from a scholarly conference in Illinois. I have titled my remarks “Writing about the Prophet Joseph Smith.”

I. Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor

I begin with the Nauvoo Expositor. Under the leadership of Mayor Joseph Smith, the Nauvoo City Council suppressed that opposition newspaper by destroying the press, scattering the type, and burning the remaining copies. That suppression led directly to the arrest and murder of Joseph Smith and is therefore an extremely significant event in his life. He has been roundly criticized for this action against a newspaper, even by Latter-day Saint writers. B. H. Roberts declared that “the attempt at legal justification [for the suppression] is not convincing,”[1] and Professor G. Homer Durham, later our Church historian, referred to this as “the great Mormon mistake.”[2]

The Nauvoo Expositor building, by B.H. Roberts. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

The Nauvoo Expositor building, by B.H. Roberts. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

My interest in this subject began in about 1958 with an inspired experience in the library of the law firm where I was employed after graduation. During a rest break, my attention was drawn to the library’s top shelf, which stored legal briefs that firm had filed in the famous 1931 case of Near v. Minnesota. There, the United States Supreme Court first applied the United States Constitution Bill of Rights to reverse the action of a state government. Curious, I examined the briefs and learned that the facts of this famous case involved the suppression of a scurrilous newspaper by government action. That case was astonishingly similar to the Nauvoo City Council’s suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor. This persuaded me that I had to learn more about that Nauvoo event.

A few years later I became an associate professor of law at the University of Chicago and was expected to do scholarly work. My first publication was a law review article on the suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor.[3] In research for that article I learned that modern criticism of the action of the Nauvoo City Council has been based on the principle of freedom of speech and press embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. However, that amendment was not adopted until twenty years after the Nauvoo suppression. The law in 1844, including interpretation of state constitutional guarantees of a free press, offered considerable support for what Nauvoo had done. Even in the similar circumstances of the newspaper suppressed in the famous case of Near v. Minnesota, a unanimous Minnesota Supreme Court and four justices in the minority in the United States Supreme Court found no violation of the free press guarantee as understood up to that time. Consequently, my article concluded that “the common assumption of historians that the action taken by the [Nauvoo] city council to suppress the paper as a nuisance was entirely illegal is not well founded.”

The lesson I drew from this scholarly research and publication has made me a lifelong opponent of the technique of presentism—relying on current perspectives and culture to criticize official or personal actions in the past. Past actions should be judged by the laws and culture of their time.

II. Carthage Conspiracy

Carthage Conspiracy, my only book on Joseph Smith, was coauthored with Marvin S. Hill.[4] Our friendship began when we were both students at the University of Chicago in the 1950s. He was working on a PhD in history, and I was studying law. In research for his dissertation, Hill learned that nine men were tried for the murder of Joseph Smith. For many years he urged me to do some legal research on that trial, which was then almost entirely unknown in our Church history.

I was slow to respond, assuming that legal records on that 1845 trial were nonexistent. I even assumed that the murderers were punished with horrible deaths such as those recited in the popular book The Fate of the Persecutors of the Prophet Joseph Smith.[5] Eventually, I was persuaded to do some preliminary research. Looking back, I believe this was the prompting of the Spirit. Then a law professor, I had time for research, and writing in legal history would help fit my expected scholarly production.

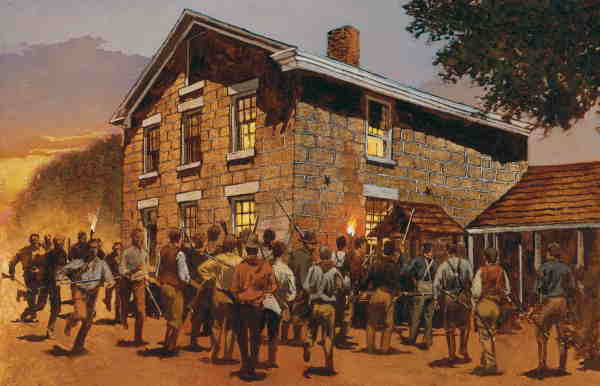

Mob at Carthage Jail, by William Maugham.

Mob at Carthage Jail, by William Maugham.

I drove to the Hancock County courthouse, some 250 miles southwest of Chicago. Fortunately, I gave the court clerks my University of Chicago Law School business card and did not tell them I was a Latter-day Saint. (There was still a lot of anti-Mormon prejudice in Carthage at that time.) They gave me access to a large room, where I searched for an index to the hundreds of records it contained. Miraculously, I was blessed to find an ancient index volume that contained the name of the first defendant in the trial, Levi Williams. Opposite his name was the number 20, which I pursued to a drawer that contained a large packet of papers labeled People v. Levi Williams. It was wrapped with a paper band sealed with paste and apparently had never been opened.

I still remember vividly the experience of slitting that paper band with my thumb and having about fifty documents spill out on the table before me. The first thing I saw was the signature of John Taylor on a complaint against nine individuals for murdering Joseph Smith. (Charges for the murder of Hyrum were separate.) Other papers contained the indictment, subpoenas for witnesses, names of the many prospective jurors who were summoned, and the names of those jurors who ultimately served. There was even the written verdict of not guilty. Here was everything but a record of the testimony at that trial. “We have a book!” I told Marvin Hill, and indeed we had.[6]

For over ten years, Hill and I scoured libraries and archives across the nation to find every scrap of information about those involved in this trial. We studied the actions and words of Illinois citizens who knew Joseph Smith personally—some who hated him and plotted to kill him and others who loved him and risked their lives to assist him. Nothing we found cast any doubt on the integrity of the Prophet Joseph Smith.

Absent from the courthouse files—but essential to a book on the trial—were records of the testimony of the witnesses. This omission was typical in trials of that period. Fortunately, there was so much interest in this trial that several observers, including lawyers, kept notes of the testimony given. Some of these were signed with the observer’s name, but the fullest set of notes, which we found in the Church Historian’s office, was unsigned. We assumed these were the notes of George Watt, the Church’s official scribe, who was sent to record the proceedings of the trial.

Here occurred another of many miracles we experienced in our research. After our book manuscript was completed and would soon be submitted to the publisher, a strong impression led me to a pile of fifty or sixty books and monographs stacked on the table behind my desk at BYU. Having no reason or special object to search that pile, I nevertheless followed the impression. There I was led to a printed catalog of the contents of the Wilford C. Wood Museum, prepared by Professor LaMar Berrett and sent to me over a year earlier. Flipping through the pages of that catalog, I found a description of a manuscript of testimony at the Carthage trial. It was identified as having been purchased by Wilford Wood in his notable gatherings in Illinois and then given to the Church. I recognized that description as the trial minutes we had found in the archives and mistakenly thought were those of George Watt. With that clarification, we searched again in the Church records and finally located George Watt’s official and highly authentic set of minutes on the trial testimony. This completed our research of that important subject and significantly enhanced the accuracy of our account of the testimony at the trial.

To me, that experience is cherished evidence of how the Lord will help us in our righteous professional pursuits when we seek guidance and are sensitive to the promptings of His Spirit.

The rest, including the acquittal of the nine individuals by an overly biased jury, is, as we say, a matter of history. Of current interest is that Carthage Conspiracy is still in print more than forty-five years after it was published by the University of Illinois Press. Last year, it sold 324 copies.

III. The Prophet Joseph Smith’s Bankruptcy and Property at Death

The most significant of my writings about Joseph Smith began small but gradually expanded into many legal proceedings that illuminated important subjects previously unknown.

Joseph Smith’s unsuccessful application to erase his debts in bankruptcy had been mentioned in passing by Church historians but never explored. In 1967 Joseph I. Bentley, a brilliant law student at the University of Chicago Law School, registered for individual research under my direction. I suggested that he look into the bankruptcy proceeding. Bentley’s efforts launched the two of us on a decade of research and collaboration involving many previously unknown legal proceedings in Illinois state and federal courts.

In those efforts, we first learned why Joseph Smith was never discharged in bankruptcy. We discovered the disposition of his personal property by intestacy. Most important, we discovered why, after his death, the Church received nothing from the Church’s extensive property holdings in Nauvoo. In contrast, Emma Smith succeeded to the largest proportion of what had been Church property. This is how she and her second husband obtained ownership of the Mansion House and other key properties in Nauvoo. Our discoveries offered important insights into the strained relations between Emma and Brigham Young. These are important questions, so it is no surprise that two lawyers wondered why we were the first researchers to seek out these records and write about them.

The Oaks and Bentley article on Joseph Smith’s bankruptcy proceeding, published in the BYU Law Review of 1976,[7] is fifty pages in length—too long to attempt to summarize here. I will therefore limit my comments to major generalizations from its contents.[8]

First, Joseph Smith’s bankruptcy application took place only a few months after his extensive efforts—well known in our Church history—to separate his personal property from the property he held on behalf of the Church. If those efforts had been legally successful, they would have prevented the tragic condition of the Church’s legal affairs after Joseph’s death. However, for reasons explained hereafter—notably bad legal advice—the needed legal separation failed to achieve its intended purpose.

Second, Joseph Smith died without a will. Under Illinois law, his property would therefore be divided, after payment of creditors, among his widow and children. Administrators were appointed to carry out that law, but they determined that the total claims of Joseph’s creditors were about three times greater than the value of the property he owned, so Emma and the children would receive nothing. But before that intestate administration was concluded, it was effectively superseded by a suit filed by the United States, one of the creditors. Jurisdiction then transferred to the federal court in Springfield, Illinois. More on that later.

Third, fortunately Bentley and I were able to find in the Federal Records Center in Chicago the voluminous records of the United States suit against Joseph as his creditor and other federal cases relating to Joseph Smith’s property. We also found correspondence related to the bankruptcy that explained why Joseph and a few others did not have their 1842 debts discharged in bankruptcy. In contrast to about 1,400 successful applicants in Illinois at that time, Joseph Smith was blocked by the objection of the United States, one of his largest creditors. That objection relied on John C. Bennett’s recently published claims that Joseph had fraudulently transferred some of his own property to avoid paying his personal debts. This referred to his attempted transfer of Church property held in his personal name to himself as trustee for the Church. Joseph’s bankruptcy application was put on hold, and that was still the status of the matter when he was martyred.

Fourth, after a succession of court proceedings covering nearly a decade (because of political reasons not involving the Latter-day Saints, who had long since departed for the West), a federal judge issued a lengthy decree, which we found and studied. The various claims that Joseph had been guilty of fraud in his 1842 conveyances were discarded by the court, which ruled on two other legal theories. The United States prevailed over all other creditors because of the priority of its lien under an earlier default judgment on a debt owed by Joseph Smith and others as sureties on a note given to purchase a steamboat (not the well-known Maid of Iowa). Additionally, and most important for purposes of Church history, Joseph’s 1842 conveyances of extensive Church properties in Nauvoo from himself in his personal capacity to himself as trustee for the Church were all held to be invalid. This result was required by an Illinois law that should have been known by the lawyers who advised these transactions. Following an ancient English limitation, Illinois law then limited a Church trustee to holding no more than 10 acres of land, but Joseph’s 1842 conveyances in trust involved about 4,000 acres, plus 312 town lots.

Fifth, as a result of the federal court’s decree, extensive properties assumed to be owned by the Church (and mostly already sold by the Church to individual landowners) were still owned by Joseph at the time of his death and therefore subject to satisfying his debts and the legal marital claims of his surviving widow, Emma. The total value of Joseph’s properties—mostly what was brought back into his estate by the federal decree—was $11,148. The court valued Emma’s dower claim (a life interest in one-third of all Joseph’s real estate) at one-sixth of all the cash in the estate. As a result, Emma Smith Bidamon received $1,809, and the United States government received $7,870. Those distributions, plus costs and expenses of $1,469, used up the property, so the other claimants against the estate, including people who purchased land from the Church, received nothing. The consequence of all that was devastating for the Church: there were no resources to help with the western move, and it was a final blow to the reputation of the Church in Hancock County.

As I have looked at this circumstance, I have concluded that the different positions of Emma and Brigham on who should own the properties that Joseph sought to convey to the Church in 1842 can be summarized as follows. In fairness and equity, these properties belonged to the Church when Joseph died. Brigham Young must have felt this. But Emma had a clear legal right under the law of Illinois. She had suffered much deprivation during her marriage and was now left a widow with children to raise. She insisted only on what was legally hers. However, it is easy to see why the Church in Utah was aggrieved when she used that property to secure legal ownership of the Mansion House and other nearby properties for her and her new husband, Lewis Bidamon.

IV. Library of Congress Speech

In 2005 the Library of Congress partnered with BYU for a two-day conference on the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of Joseph Smith. Its stated object was to examine “the religious, social, and theological contributions of Joseph Smith.” Scholars from throughout the United States and some other countries were invited to the library’s Coolidge Auditorium to present papers. I represented the Church and gave a paper on the suggested subject “Joseph Smith in a Personal World.”[9]

Here are some examples of what I was prompted to say about the Prophet’s personal qualities:

One of [Joseph’s] personal gifts is evidenced by the love and loyalty of the remarkable people who followed him. . . . [He] had a “native cheery temperament” that endeared him to almost everyone who knew him. We have record of many adoring tributes like that of an acquaintance who said, “The love the saints had for him was inexpressible.”[10]

Great Hall of the Library of Congress, 2005. Photograph courtesy of Shirley S. Ricks.

Great Hall of the Library of Congress, 2005. Photograph courtesy of Shirley S. Ricks.

I continued with this:

The Joseph Smith I met in my personal research was a man of the frontier—young, emotional, dynamic, and so loved and approachable by his people that they often called him “Brother Joseph.” His comparative youth overarched his prophetic ministry. He was fourteen at the time of the First Vision, twenty-one when he received the golden plates, and just twenty-three when he finished translating the Book of Mormon (in less than 75 working days). Over half of the revelations in our Doctrine and Covenants were given through this prophet when he was twenty-five or younger. He was twenty-six when the First Presidency was organized, and just over thirty-three when he escaped from imprisonment in Missouri and resumed leadership of the Saints gathering in Nauvoo. He was only thirty-eight and a half when he was murdered.[11]

I departed from my assigned subject to help the audience understand Joseph Smith as a prophet and his vital teachings about revelation. I said, “Revelation is the key to the uniqueness of Joseph Smith’s message,” adding that “revelation is the foundation of our church doctrine and governance” and that “Joseph Smith affirmed by countless teachings and personal experiences that revelation did not cease with the early apostles, but that it continued in his day and continues in ours.” “‘The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was founded upon direct revelation,’ Joseph Smith declared, ‘as the true Church of God has ever been.’”[12]

Like the other Latter-day Saint speakers at the conference (eight of the seventeen), I also spoke about the importance of the Book of Mormon. I quoted Joseph’s great teaching: “‘Take away the Book of Mormon and the revelations and where is our religion?’” he asked. ‘“We have none,’” he answered. I explained, “The stated purpose of the Book of Mormon is to witness that Jesus is the Christ.” As Joseph proclaimed, “The fundamental principles of our religion are the testimony of the Apostles and Prophets, concerning Jesus Christ.”[13]

As I look back on that event, the thing I remember best is what the nine scholars not of my faith did not say about Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon. They concentrated on various subjects in Joseph’s life and his influence, but only one speaker discussed the Book of Mormon further than just referring to it by name. Professor Robert V. Remini, a University of Illinois historian, who also served as the US Congressional Historian, gave this admiring description: “What is truly remarkable—really miraculous—[Professor Remini said] is the fact that this massive translation was completed in sixty working days by an uneducated but highly imaginative zealot steeped in the religious fervor of his age. As a writer [he said], I find that feat absolutely incredible. Sixty days! Two months to produce a work running over six hundred pages and of such complexity and density. Unbelievable.”[14] Significantly this description falls far short of explaining how Joseph produced this central witness of his prophetic ministry.

The only other non–Latter-day Saint comment about the Book of Mormon came from Margaret Barker of Great Britain, a Methodist preacher and authority on the Old Testament. While this statement was not included in the published version of her talk, I am sure I remember her explaining that she was not saying anything about the Book of Mormon because she had no explanation for it.

V. Legal History Conference in Illinois

Another opportunity to teach about Joseph Smith came to me in an unusual way. Through their Historic Preservation Commission and the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, the Illinois Supreme Court had a program to publicize significant legal events rooted in Illinois. A justice of that court phoned me to ask if the Church would assist them in looking into Joseph Smith’s legal cases in Illinois. Of course, we would. I put her in touch with some of our scholars, who recommended focusing on the three unsuccessful attempts to extradite Joseph Smith from Illinois to face criminal charges in Missouri. So it was that in 2013, the Historic Commission and the Lincoln Library convened a two-day conference in Springfield, Illinois, on those historical and constitutional developments.

To get the Latter-day Saint background of those events, the first session of the conference was convened the preceding evening in Nauvoo. I was invited to introduce Joseph Smith, the central figure in these extradition proceedings. I chose two subjects for my introduction: first, the background of Joseph Smith, and second, the writ of habeas corpus, which was the legal procedure by which Illinois courts—state and federal—reviewed these Missouri attempts. By “coincidence,” I had a good background on each of these subjects. As a young law professor more than fifty years earlier, I had published three law review articles on habeas corpus, including one on the use of this writ in state courts in the nineteenth century. I won’t bore you with any of that but will speak only of some of the subjects I mentioned in my address to the dignitaries who had driven to Nauvoo, including a former governor of Illinois.

The Illinois sponsors likely chose a major two-day program on Joseph Smith because Missouri’s attempts to extradite a person of Joseph Smith’s prominence involved key issues in that period of American history. Leading up to the Civil War, the most important legal issues in the United States involved contests between state power and federal power. During our Nauvoo period, the great promises in the United States Constitution were being tested by the often violent actions of state authorities, such as Missouri’s expulsion of Latter-day Saints and the contested issue of slavery. What could the federal government do about state laws or actions against persecuted persons?

To make the audience acquainted with Joseph Smith’s feelings about the United States Constitution, I quoted several of his statements.

The Constitution of the United States is a glorious standard; it is founded in the wisdom of God. It is a heavenly banner.[15]

I am the greatest advocate of the Constitution of the United States there is on the earth. In my feelings I am always ready to die for the protection of the weak and oppressed in their just rights.”[16]

I should have continued that last quote with these words he spoke next in his 1843 sermon in Nauvoo:

The only fault I find with the Constitution is, it is not broad enough to cover the whole ground.[17]

Although it provides that all men shall enjoy religious freedom, yet it does not provide the manner by which that freedom can be preserved. . . . Its sentiments are good, but it provides no means of enforcing them.[18]

Joseph Smith loved the Constitution and hoped that its promises could be used more effectively to protect his people. In his extradition cases, they were. I gave the audience this summary:

All three of Joseph Smith’s extradition proceedings had the same result. The judges refused to send him back to Missouri for criminal prosecutions and confinement that would most likely have resulted in his death. In a nation struggling to balance the rights of majority and minority, the courts acted to protect a persecuted prophet from what would probably have been his death in that state.[19]

I avoided describing the legal technicalities in these extradition hearings, which later speakers explored in Springfield. Similarly here, I will avoid reviewing details known to this knowledgeable audience. Instead, I will mention the prominent participants and circumstances in these three hearings, sometimes with my own summaries and sometimes quoting what I said in Nauvoo.

Some who participated in Joseph’s hearings later became nationally prominent. The judge in his first extradition hearing was young Stephen A. Douglas, who had just been appointed to the Illinois Supreme Court. Representing Joseph was Orville Browning, who later served as a US senator and attorney general of the United States. In his defense of Joseph, Browning told the judge about the sacrifices and horrors of the Latter-day Saints’ expulsion from Missouri. He added this about Joseph:

And shall this unfortunate man, whom their fury has seen proper to select for sacrifice, be driven into such a savage band, and none dare to enlist in the cause of justice? If there was no other voice under heaven ever to be heard in this cause, gladly would I stand alone, and proudly spend my latest breath in defense of an oppressed American citizen.[20]

In a later extradition case, Joseph was represented by the renowned Chicagoan, Justin Butterfield, then the highest-ranking lawyer in the state, as the US attorney for Illinois. His advocacy included this conclusion:

I do not think the defendant ought under any circumstances to be delivered up to Missouri. It is a matter of history that he and his people have been murdered and driven from the state. He had better been sent to the gallows. He is an innocent and unoffending man.[21]

Finally, I quote my conclusion to the conference audience in Nauvoo:

Joseph Smith’s character was perhaps best summed up by men who knew him best and stood closest to him in church leadership. They adored him. Brigham Young declared, “I do not think that a man lives on the earth that knew [Joseph Smith] any better than I did; and I am bold to say that, Jesus Christ excepted, no better man ever lived or does live upon this earth.” One does not need to agree with that superlative to conclude that the man whose legal contests will be dramatized tomorrow in Springfield was, indeed, a remarkable man, a great American, and one whom I and millions of our current countrymen honor as a prophet of God.[22]

That statement also serves as my conclusion to this audience, as well as my testimony of the divine ministry of the Prophet Joseph Smith. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Notes

[1] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930), 2:232.

[2] G. Homer Durham, “A Political Interpretation of Mormon History,” Pacific Historical Review 13 (1944): 136, 140.

[3] Dallin H. Oaks, “The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor,” University of Utah Law Review 9 (Winter 1965): 862–903.

[4] Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill, Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1975).

[5] N. B. Lundwall, comp., The Fate of the Persecutors of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1952).

[6] Throughout our research and writing, Hill and I were surprised that historians had not preceded us in finding the original records and writing about this important event in Church history.

[7] Dallin H. Oaks and Joseph I. Bentley, “Joseph Smith and Legal Process: In the Wake of the Steamboat Nauvoo,” BYU Law Review 3 (1976): 735–82; the shortened version was reprinted in BYU Studies 19, no. 2 (1979): 67–99.

[8] I omit here Bentley’s significant expansions and clarifications resulting from his further impressive research, published in the Journal of Mormon History in 2009.

[9] Dallin H. Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 153–72; see John W. Welch, ed., The Worlds of Joseph Smith: A Bicentennial Conference at the Library of Congress (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2006), 259–60.

[10] Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” 159–60.

[11] Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” 159.

[12] Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” 153–55.

[13] Oaks, “Joseph Smith in a Personal World,” 153, 157.

[14] Robert V. Remini, “Biographical Reflections on the American Joseph Smith,” BYU Studies 44, no. 4 (2005): 27.

[15] Millennial Star, December 1840, 197; Joseph Smith letter to Edward Partridge and the Church, 22 March 1839, Revelations Collection, Church History Library.

[16] Sermon on 15 October 1843, Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, volume E-1, 1 July 1843–30 April 1844, p. 1754, josephsmithpapers.org.

[17] Sermon on 15 October 1843.

[18] Sermon on 15 October 1843.

[19] Dallin H. Oaks, “Behind the Extraditions: Joseph Smith, the Man and the Prophet,” address at Historic Nauvoo Visitors’ Center, Nauvoo, Illinois, 23 September 2013; see https://

[20] Oaks, “Behind the Extraditions,” 2.

[21] Oaks, “Behind the Extraditions,” 6.

[22] Oaks, “Behind the Extraditions,” 22.