Richard E. Bennett, “Quiet Revivalism: New Light on the Burned-Over District,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 89‒108.

Richard E. Bennett is a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

When the terrors of wind, earthquake and fire have been useful to prepare the way, to usher in the designed manifestations of the divine glory, the Lord gives a divine calmness of the spirit, and comes in as a still small voice.[1]

The following week was the most interesting and solemn this village [Whitestown] ever witnessed. Some of the most intelligent and respectable people in the place were convicted of sin. Silence reigned. No opposition was heard. Christians trembled. They felt that God was here, and that the village was awed to silence and prostrated before the majesty of his character. . . . I felt as though all I could do was to urge Christians to pray, that breath might enter these slain.[2]

The spirit of religious revivalism that spread into western upstate New York in the early nineteenth century has been well described in Whitney Cross’s study of the “burned-over district.”[3] So many zealous men of the cloth were vying for converts, and so many revivals and torch-lit camp meetings were being staged that the area seemed almost burned over with religious excess. As Joseph Smith indicated, “There was in the place where we lived an unusual excitement on the subject of religion” (Joseph Smith—History 1:5)—an understatement, to say the least.

While readily admitting that the sound and fury of these well-known outdoor revival meetings, with their mighty calls to faith and repentance, wielded a profound effect upon their many adherents, including those in and near Palmyra, my purpose is to explore a very different side of the story: to recognize that this mighty spirit of revivalism or “precious season of divine visitation by the Holy Ghost”[4] took on many other forms, whether Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, or even German Reformed. This revival of religion was so intensely quiet, so profoundly personal, and so awfully still that it formed a remarkable counterpoint to what many have assumed the spirit of revivalism meant in western New York in the age of 1820. These “reviving and converting influences of the Holy Spirit,” this “season of refreshing from on high,” reached Palmyra not only via the sounds and excitements of outdoor camp meetings.[5] These influences also owed much, if not everything, to dedicated missionaries and ministers who called upon friends and family in the sanctity of their own cabin homes by the fire and the hearth to seek the Lord through mighty private prayer for forgiveness and salvation. Besides this, there was the personal outreach of female missionaries and visiting teachers—a very intimate, deeply personalized revival of faith and a face-to-face invitation to repent and come unto Christ, which I am terming quiet revivalism.

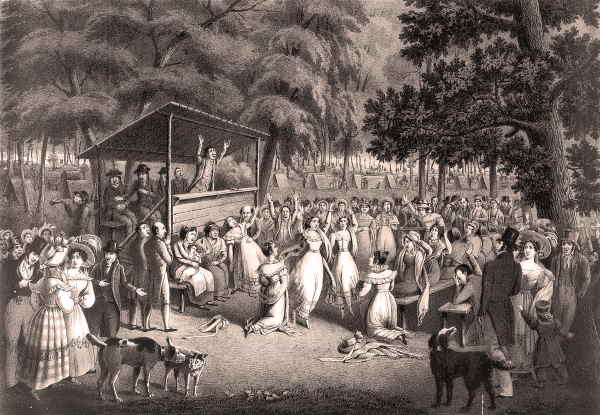

Lithograph of a religious camp meeting ca. 1829, by Alexander Rider.

Lithograph of a religious camp meeting ca. 1829, by Alexander Rider.

While it was the Methodists who came to dominate the shouts and shrills of the outdoor camp meetings of the Second Great Awakening in upstate New York in the early nineteenth century, such “protracted meetings”—as many Calvinists derisively termed them—had actually begun with a Presbyterian minister, the Reverend James McGready of Pennsylvania. Having moved to Kentucky in 1798, McGready employed a powerful, if unpolished, preaching style that attracted so many followers that no single edifice could begin to hold them all. In the ensuing Western (or Kentucky) Great Revival, which almost amounted to “godly hysteria,” McGready and his fellow preachers conceived the idea of a religious service of several days’ length held outdoors for vast numbers of followers who were obliged to eat and find shelter far from home. Best remembered was his monster meeting at Cane Ridge in 1801, when some twenty thousand people congregated for days on end to listen to one sermon after another. With preachers standing, shouting, and exhorting from wagons or tree stumps, something was bound to happen. McGready’s listeners spontaneously began shrieking and groaning and shouting amens and hallelujahs with thunder, lightning, and horses’ whinnying all thrown in for good measure. Soon such a grand cacophony of bustle and noise erupted that some described it as a “sound like the roar of Niagara.”[6]

If Presbyterianism had trouble constraining the passions of the revival, “Methodism was made for it.”[7] By 1805 the Methodists had taken over most of these outdoor camp meetings and given them new structure, a more defined purpose, and much more careful planning and preparation. By so doing, the Methodist camp meeting regularly attracted crowds commonly in excess of twenty thousand people, often lasting days at a time.[8] Far from being a mere religious, circus-like spectacle, at issue in these revivals was a heightened personal sense of sin, a yearning for forgiveness, and a belief in one’s freedom to change his or her life. It was for so many a matter of personal choice to seek salvation, now or never.[9]

The central physical feature of the Methodist camp meetings was the wooden pulpit, often placed under roofed platforms, set up at one or both ends of an outdoor amphitheater and oriented to face parallel rows of circular or horizontal hewn-log seating. Conspicuously placed in front of the pulpit was the so-called “mourning bench” or “anxious seat” to which sinners seeking forgiveness made their way in order to seek salvation. The aisles and rows were filled with straw to make kneeling prayer more comfortable. Beyond the benches were many tents, wagons, carriages, and horses to which the crowds reverted at night or between meetings for meals, rest, and refreshment. Lighting came from flickering lamps, candles, tent fires, and torches attached to trees or set on six-foot-high wooden tripods throughout the camp, allowing meetings to last far into the night. Women sat on the right and the men on the left, many armed with scriptures in hand. Depending on the size of the crowd, there could be several adjacent arenas or amphitheaters prepared with as many as twenty to thirty ministers, several preaching simultaneously.

As one “soul-melting minister” followed after another, they earnestly called on everyone within the sound of their voices and within the scope of their fierce eyes to repent before it became everlastingly too late. Oftentimes, Methodists would frequently debate their Presbyterian colleagues, with the Baptists often joining in the fray. At the end of such rounds of preaching, with or without invitation, the assembled throngs would often stand and break out in singing such soul-stirring hymns as “Shout Old Satan’s Kingdom Down”:

This day my soul has caught new fire—Hallelujah!

I feel that heaven is coming nearer, O glory Hallelujah!

(Chorus)

Shout, shout, we’re gaining ground, Hallelujah!

We’ll shout old Satan’s kingdom down, Hallelujah!

When Christians pray, the devil runs, Hallelujah!

And leaves the field to Zion’s sons, O glory Hallelujah![10]

It would be an egregious error, however, to paint the burned-over district revivals with only the loud zealotry and emotional excesses of outdoor camp meetings. At issue here is the very definition of the term revival. If many Methodists were massing in support of the loud and boisterous outdoor camp meetings, most contemporary Presbyterian/

Certainly, such had been the experience of Joseph Smith’s mother, Lucy, who along with three of her children—Hyrum, Sophronia, and Samuel—converted to Presbyterianism sometime after the family had moved to Palmyra from Vermont.[12] This may not be too surprising, considering the fact that Lucy Mack Smith had been reared by a devout Congregationalist mother and that Lucy had made a previous covenant with God for sparing her life; however, it should be remembered that she had been earlier offended by Presbyterian preaching. “It did not fill the aching void within nor satisfy the craving hunger of my soul,” she later admitted. Instead, she determined to turn to her Bible to be her “guide to life and salvation.”[13] However, something would happen with her experience with Presbyterianism and the messengers of that faith that eventually led her back to her Calvinist beliefs.

William Smith, a younger brother to Joseph Smith, remembered that it was his mother Lucy who, sometime after their removal to New York, “prevailed on us to attend the meetings, and almost the whole family became interested in the matter, and seekers after truth. She continued her importunities and exertions to interest us in the importance of seeking for the salvation of our immortal souls, until almost all the family became either converted or seriously inclined.”[14]

By way of background, one of the earliest churches in all of western New York, and certainly in the Phelps-Gorham purchase (roughly Ontario and Wayne counties), was the Congregational Church. It was established in Palmyra in 1793 under the Reverend Ira Condict just four years after General John Swift and John Jenkins had purchased the region and after Stephen Reeves, David H. Foster, and several other Presbyterian elders had moved into the area from Long Island around the same time. After a Mr. Johnson and Rev. Eleazer Fairbanks held the pulpit from 1795 until the early 1800s, a Mr. Lane, “an Englishman, who had received a license to preach in the Wesleyan connexion in England” but who had no affiliation with any ecclesiastical body in the area, served until 1806.[15] In 1807 the Congregational Church adopted the Presbyterian form of government. Succeeding Lane was Rev. Benjamin Bell in 1807, followed by Rev. Hippocrates Rowe from 1811 to 1816, and then by Stephen M. Wheelock. The Presbyterians erected their first house of worship in Palmyra in 1811, a fifty-by-forty-foot wooden frame structure with a steeple. It later burned down, and a new brick edifice replaced it in 1832—this time with both a steeple and a bell.

The years 1816 and 1817, just as the Smith family arrived from Vermont, were particularly years “of the right hand of the Most High” in which the Palmyra church revived in both spirit and numbers.[16] The result was that in 1817 it divided into two separate congregations, one on the east side of Palmyra and the other on the west. Rev. Benjamin Bailey was minister of the eastern church beginning in 1817 and was followed by Francis Pomeroy from 1825 to 1831. The Western Presbyterian Church of Palmyra saw Stephen M. Wheelock and the Rev. Jesse Townsend as ministers from 1817 till 1821. Townsend was replaced by Rev. Benjamin B. Stockton, who served until 1827.[17] How often Joseph Smith attended Palmyra’s Western Presbyterian Church is unknown; but late in life, Lorenzo Saunders, a childhood acquaintance, recalled that the first time he ever attended Sabbath School was when he went with “young Joe Smith at the old Presbyterian Church.”[18]

It is important to understand what the term revival meant at that time to these men of the cloth. While it is true that later Presbyterian divines such as Charles Finney turned to outdoor camp meetings as the means of grace, most Old and New School Presbyterian pastors preferred a much different path to personal conversion, a form of quiet revivalism that extended into the parlor of most Palmyra homes.

Such a personal, much more subdued approach to the revival of local religion is epitomized in the work of two powerfully persuasive Calvinist preachers—the Reverend Asahel Nettleton (1783–1844) and James H. Hotchkin (1781–1851). The latter, an ordained Presbyterian minister, authored a six-hundred-page book detailing the history of Presbyterian church work in western New York—most particularly in Ontario and Wayne Counties. Having crisscrossed the region for over forty-seven years, Hotchkin knew more about the Presbyterian church, its ministers, and its kinds of revivals than perhaps any other person of the day.

“As to the character of the revivals in Western New York of this period,” Hotchkin wrote,

the author [Hotchkin] is not aware that there was anything peculiar in them to distinguish them from the revivals of preceding times. No new measures were adopted . . . but such an order of ministers as evangelists, or technically called “revival preachers” whose business it was to go from place to place and “get up a revival,” and by the use of peculiar instrumentalities, effect the conversion of a great many souls, was not then known . . . [rather], [it was] the genuine work of the Holy Spirit of God.[19]

What Hopkins and others meant by revival was “nothing but the foolishness of preaching, a plain and faithful exhibition of gospel truth, the instruction of Sabbath schools, and Bible classes, and private addresses to the consciences of the impenitent. In almost or quite every case, we have heard of the conversion of sinners being preceded by a very uncommon spirit of prayer.”[20] At these and other times, ministers would weigh in against such sins as “Sabbath-breaking, drinking, gambling, carousing, horse-racing, dancing, and attending the theater” and exhort their listeners by “covenant” to abandon such things and live by the Westminster Confession of Faith.[21] George Marsden put it more succinctly: “Evangelicals were thoroughly convinced that it was their most solemn duty to mind everyone else’s moral business.”[22] Hotchkin referred to this kind of revivalism as “the more excellent way,” characterized not by the “anxious seat” for sinners but by “inquiring meetings,” individual sunrise prayer hours, weekly group prayer circles, and individualized invitations to faith and repentance. The goal of such revivals was to increase membership, boost church attendance, and restore “a moral and religious tone of character” to the place.[23]

Women played a most important role, particularly in the Presbyterian revivals. Mothers, often accompanied by their little children, came together in united prayer. A particularly effective way to setting up these kinds of revivals was to have women and men go in pairs to visit each home in the area “in awakening attention, and bringing numbers to the house of God.”[24] Many female partnerships, particularly widows, went from house to house encouraging the households to pray as families and individuals, to hold anxious meetings of whispering or conversing individually with God, and to search the scriptures. In these and other intimate ways, these home visitors furthered the flame of the local revival by challenging individuals to change the course of their lives, repent of their sins, and return their lives to God. Women clearly were a numerical majority not only within Presbyterian circles but also among Methodists, and women formed the backbone of all kinds of revivals.[25]

Oftentimes local overworked Presbyterian and Congregational ministers would request itinerant preachers and specially called missionaries from New England to assist them in their soul-saving endeavors. One such remarkable itinerant preacher who personified precisely this kind of quiet revivalism was Rev. Asahel Nettleton. Graduating from Yale College in 1811 as an ordained Congregationalist minister, Nettleton had declined a life of foreign missionary service in favor of pursuing Christian revivalism closer to home. Kind and courteous, conscientious and exemplary, unassuming and unostentatious, Rev. Nettleton began his ministry in the college town of New Haven.[26] As the fire of the Second Great Awakening swept into upstate New York, Nettleton accepted offers to conduct revivals in Schenectady, Nassau, Malta, Galway, and several other communities east of the Finger Lakes region in early 1819 through early 1820. Critical of the loud exhibition of religion so dominant in outdoor camp meetings, Nettleton believed that the “Spirit of Prayer,” which he ever regarded as the unfailing precursor of a revival of religion, has been “dragged from her closet, and so rudely handled by some of her professed friends, that she has not only lost all her wonted loveliness, but is now stalking the streets in some places stark mad.”[27]

Asahel Nettleton was an American theologist and Evangelist from Connecticut who was highly influential during the Second Great Awakening. Painting by Samuel Lovett Waldo (1783-1861); William Jewett (1789-1874); Connecticut Historical Society.

Asahel Nettleton was an American theologist and Evangelist from Connecticut who was highly influential during the Second Great Awakening. Painting by Samuel Lovett Waldo (1783-1861); William Jewett (1789-1874); Connecticut Historical Society.

Rev. Hotchkin disparaged itinerant ministers who preached at outdoor camp meetings even more roundly than did Nettleton: “Many of them were destitute of classical and theological furniture; of feeble natural abilities; erroneous in sentiments, boisterous, vulgar, and abusive in their manner of preaching; irreverent and even dictatorial in prayer, and fanatical in their whole procedure.” Rev. Hotchkin continued, “It is not, however, to be understood, that this class of evangelists were generally countenanced and upheld by the ministers and churches of the Presbyterian denomination of Western New York. This was by no means the case.”[28]

Refusing to preach in any community to which he had not been invited, Nettleton proved remarkably successful. Wherever he went, his style of preaching converted many people, some say as many as thirty thousand.[29] Not surprisingly, he roundly rejected the methodologies of some of his contemporaries, particularly the better-known fellow Calvinist revivalist, Charles Grandison Finney, and Nettleton became Finney’s most vocal critic. Nettleton argued that Finney, who was converted in 1821, preached with “false affections” that “often [rose] higher than those that are genuine” and “unless checked, [those] false affections could ruin a revival.”[30] While it is true that when at the pulpit, Nettleton could be remarkably clear and forcible in his illustration of a sinner’s total depravity and in his or her utter inability to procure salvation by unregenerate works or any “desperate efforts,”[31] Nettleton as preacher ever exhorted with grace. As to his quiet effectiveness, one of his disciples wrote the following: “This evening we met in the school house. The room was crowded, and the meeting was exceedingly joyful. Every word that was spoken, seemed to find a place in some heart. ‘Old things are passed away, and all things are become new.’”[32]

The key to Nettleton’s success, and that of many of his contemporary itinerant colleagues, was not only his plain, simple style of instructive preaching but even more so his fatherly care and concern for the individual. Shunning large, camp meeting–style assemblies as previously described, Nettleton discouraged fanaticism, alcohol, confusion, and loud, disorderly conduct of any kind, choosing the more intimate pathways to individual conversion rather than the confessional exercise of the public mourner’s bench. He liked to differentiate between “true and false zeal,” between the real and the counterfeit, between preachers seeking self-glory and those searching for the conversion of their listeners.

Zeal is that pure and heavenly flame,

The fire of love supplies;

While that which often bears the name,

Is self in a disguise.[33]

And he constantly criticized the “noise and bluster” of camp meetings. “The good people here are astonished at our stillness,” Nettleton wrote. “My opinion is, that had they been ten times as still, they would already have witnessed ten times as much.”[34]

Nettleton’s idea of an “anxious meeting” was to pray and fast with others one-on-one and to comfort the sick and afflicted, often walking home on byways and highways with both sinners and the saved, listening, consoling, and supporting. One such man spoke reverently of their private conversations eighteen years after the fact. “I have found Him, I have found Him, and He is a precious Savior,” he confided to Nettleton. “That night I could not sleep for joy. I do not think I closed my eyes. I found myself singing several times in the night. In the morning all nature seemed in a new dress and vocal with the praises of a God all glorious. Everything seemed changed, and I could scarcely realize that one, only yesterday so wretched, was now so happy.”[35]

Much of the spirit of Presbyterian evangelicalism in upstate New York, specifically in early 1820, began with Nettleton’s visit to Union College in Schenectady, where the sudden death of a young student in the third week of January sparked a revival of religion. In addition to Nettleton, other professors like the Reverend E. Nott (president of the college), Thomas McAuley, Walter Monteith, Halsey A. Wood, and Elisha Yale began quietly fanning out in all directions and holding “solemn assemblies”—some as far west as Geneva, New York, in what was a case of a college-inspired, quite measured revival.[36]

During 1820 in Saratoga, New York, Nettleton added fifty-five converts to the local church. In Malta, New York, the awakening spread over different parts of the town until almost all were affected. “Our meetings have been crowded and solemn as the house of death,” one preacher reported.[37] And from another: “Every house exhibited the solemnity and silence of a continued Sabbath; so profound was this stillness and solemnity, that a recent death could have added nothing to it in many families.” And in Stillwater, New York, “in a large district, though harassed by sectarian contention, there is now scarcely one house where daily prayer is not wont to be made. . . . Boatmen, tipplers, infidels and atheists, were mixed with the unholy multitude, . . . [and all] felt the power of the Holy Ghost, and yielded to his influence.” By the end of March, more than twelve hundred people had converted in the Stillwater region alone.[38] Thanks to the pioneering research efforts of the late Milton V. Backman, we know that these Presbyterian-flavored revivals bore particular fruit in 1819 and 1820, “more numerous, extensive and blessed” than in any previous years and greater than in any other state. Presbyterianism grew in New York State by 35% in 1820 with 1,513 of the 2,250 new converts coming from the burned-over district.[39]

Unlike summer outdoor camp meetings, the Presbyterian-led quiet revivals of 1820 often occurred during the dead of winter, after fall harvests and before the busy springtime planting season, as evidenced in this March 1820 report from Amsterdam, New York:

An awe! A stillness! An oppressive silence, which cannot be described. . . . It was the sinking of the wounded heart! . . . Many who visited these meetings [did so] from motives of curiosity, totally careless! Beholding the mighty power of God, [they] were terrified at their own hard and impenitent hearts; convicted of sin; awakened to a sense of the misery of their state. . . .

Sometimes, sleigh loads of convinced sinners, after leaving the meeting, and riding half a mile, or a mile, homewards, would turn back again to the place of prayer, to hear still more about the salvation of Jesus! And they often did this too, through lanes and ways and snows, that would have been deemed by persons in any other state of mind, to have been impassible.[40]

Another highly effective mode of visitation used by Nettleton and other Presbyterians was to hold indoor meetings with as many as possible of the same sex or with another homogeneous group in which those in attendance could discuss their most perplexing concerns and the deep issues attendant to personal conversion. These visits were usually made to the entire family, as well as to young men and young women specifically. Occasionally they taught American Indians and sometimes slaves,[41] all of which gave “an unembarrassed opportunity of suiting an address to the persons present.”[42]

While Rev. Nettleton may never have quite reached Palmyra itself—most of his work was in Saratoga County, some one hundred miles to the east—he certainly caught the town’s attention. The local Palmyra Register wrote in the spring of 1820 of his recent successes and of the “religious excitement” of the times in the communities east of Palmyra.[43] His style of Presbyterian preaching, his house-to-house visits, and his caring concern paint a very different picture from that of the loud Methodist-dominated camp meeting.[44] The former was as still as the latter was boisterous and may beg a revision to what some readers assume was the dominant spirit of revivalism. The preferred manner was “to go round and speak to each individual present, in a tone so low as not to be heard by others, to give a word of pointed exhortation, and close by solemn prayer. There was seldom singing in these meetings and all was solemn, still, and reflective, and if an improper person was found to have intruded . . . , Mr. Nettleton knew how to dispose of [the person].”[45] Considering Lucy Mack Smith’s serious frame of mind and convictions, her return to Presbyterianism likely owed as much to the Nettleton-like revival experience as it ever did to the roar of the outdoor camp meeting.

And it was among the youth—both young men and young women—that revivals of all kinds bore the greatest fruit and where conversion most often occurred in private, in the stillness and quiet created by seeking for answers to probing, personal prayers.[46] Indeed, as one scholar has concluded, “The most striking and consistent characteristic of the Second Great Awakening was the youthfulness of its participants.”[47] One Baptist minister writing in January 1820 about mass conversions in Cornish, New York, told of “a number of young children” from “thirteen down to seven years of age” singing hosannas to the Son of David.[48] Another Baptist minister in Bristol, Rhode Island, reported:

There are as many as four or five crowded meetings at once, at almost every hour of the day, from an early hour in the morning, until late at night. And even at the corners of our streets, you will scarcely see two or three persons together, but the great concern of the salvation of the soul is the subject of their conversation. . . .

Were I to attempt to tell you the number of young converts, who in a judgment of charity, have been brought out of darkness into God’s marvelous light, it would be utterly impossible.[49]

It was common for ministers of all faiths to report from the field that “two thirds of [the] whole number of converts [were] under 20 years of age.”[50]

Often “a sound of a going” was heard when entire schoolhouses emptied their anxious students not for mere recess but out into the nearby fields and quiet groves to pray to God above. Usually taking their Bibles in hand with them, they were encouraged to pray for an hour—and if at all possible, early in the morning at sunrise[51]—over a single verse or specific passage of scripture while soliciting heaven for the salvation of their souls. Once in their quiet place of meditation, they would then stand still and see the workings of heaven. “There you are at the place of meeting between the Spirit of God and your own spirit,” one minister reported in 1819. “You may have to wait, as if at the pool of Siloam; but the many calls of the Bible to wait upon God, to wait upon him with patience, to wait, and to be of good courage, all prove that this waiting is a frequent and a familiar part of that process by which a sinner finds his [or her] way out of darkness into the marvelous light of the gospel.”[52]

And such waiting on the Lord often bore remarkable fruit, as attested by the following 1820 letter written by a young woman to her minister friend:

From the age of 13 years I was blessed with the strivings of the Holy Spirit; but alas, I did not yield until your voice, by the Power of God, reached my heart. From that time I resolved to repent and forsake my most pleasing sins, if haply I might find that peaceful but unknown way. While in the sacred grove on the 14th of August 1818, my incessant cries reached the Father of mercies, and my benighted soul received the dawn of heaven. My confidence in God, through the atoning blood of the Dear Redeemer, has grown stronger and stronger.[53]

From this and scores of other similar descriptions, it is clear that while the answer to Joseph Smith Jr.’s teenage prayers would eventuate in the birth of a new world religion, his “determination to ask of God” on “the morning of a beautiful, clear day” and the way he went about approaching heaven that spring of 1820 were entirely consistent with the contemporary upstate New York culture of Presbyterian-led revivalism—a time known for its deeply personal, very quiet private pleadings to heaven, when young women and young men, with scriptures in hand or at least in mind, entered their own sacred groves to pray for the salvation of their souls (Joseph Smith History—1.14).

Notes

[1] Samuel Buell, A Faithful Narrative of the Remarkable Revival of Religion in the Congregation of Easthampton, on Long Island, 1764 (Sag Harbor, NY: Alden Spencer, Printer, 1808), 51–52.

[2] A Narrative of the Revival of Religion in the County of Oneida Presbytery of Oneida, in the Year 1826 (Utica: Hastings and Tracy, 1826), 19.

[3] Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-Over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800–1850 (Utica, NY: Cornell University Press, 1950).

[4] Rev. James H. Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, and of the Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Presbyterian Church in that Section (New York: M. W. Dodd, 1848), 413.

[5] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 407.

[6] Bernard A. Weisberger, They Gathered at the River: The Story of the Great Revivalists and Their Impact upon Religion in America (Boston: Little Brown, 1958), 21–28.

[7] Weisberger, They Gathered at the River, 42.

[8] See Christopher C. Jones, “The Power and Form of Godliness: Methodist Conversion Narratives and Joseph Smith’s First Vision Narratives,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no. 2 (2011): 88–114. See also Stephen J. Fleming, “John Wesley: A Methodist Foundation for the Restoration,” Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 9, no. 3 (2008): 131–49.

[9] One major reason why many Presbyterians of the “Old School” tradition opposed camp meetings was because of the Methodist preachers’ emphasis on a sinner’s ability to choose to change his or her life. Calvinist thought had long emphasized the power of the Spirit alone in one’s turning to God, not the will of the individual. However, the “New School” or Hopkinsian Calvinist view, which was then gaining popularity, gave more provision for individual initiative in choosing a more moral and righteous way of life, but it still did not deny the unsolicited, unlimited power of the Spirit—and the Spirit only—to change one’s life and behavior. See George M. Marsden, The Evangelical Mind and the New School of Presbyterian Experience. A Case Study of Thought and Theology in 19th Century America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), 35–41.

[10] Stith Mead, Hymns and Spiritual Songs (Richmond: Jacob Haas, 1807). See also George Scott, The New and Improved Camp Meeting Hymnbook (Brookfield, MA: self-pub., 1832), as cited by Sweet, Revivalism in America, 144.

[11] Congregationalists and Presbyterians had come together—“Presbygationalists”—in their Act of Union in 1801. In strict Congregational thought, the “church” was the local congregation, whereas in Presbyterian thought, the “church” was the whole company of Christians everywhere, the one body of Christ locally manifested. See Robert Hastings Nichols, Presbyterianism in New York State (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1963), 11. While the Congregationalists and Presbyterians had different views of local versus synodic authority, their Calvinistic doctrines were very much in harmony one with another. In Ontario County, New York, they had formed their own, more local Act of Union in 1812.

[12] See “Did Lucy Mack Smith Join the Presbyterian Church after Her Son, Alvin, Died in 1823?,” www.fairmormon.org.

[13] Lucy Mack Smith, Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 50.

[14] William Smith, William Smith on Mormonism (Lamoni, IA: Herald House Steam Book & Job Office, 1883), 6–7. I am indebted to Kyle R. Walker for bringing this remembrance to my attention. For more on revivalism near the Smiths’ Palmyra home, see Milton V. Backman Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision: The First Vision in Its Historical Context (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971). For a more current study, see Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision: A Guide to the Historical Accounts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012).

[15] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 375–76. This may very likely have been the Mr. George Lane with whom Joseph Smith later conversed regarding his First Vision. Other early records of western New York make reference to a Mr. Lane who was a “godly” and earnest “pioneer minister in Central and Western New York” and whose great aim was to “lengthen the cords and strengthen the stakes of the Church.” History of Rochester Presbytery from the Earliest Settlement of the Country (Rochester, NY: Rochester Presbytery, 1889), 76.

[16] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 126, 378.

[17] William Smith, Joseph Smith’s younger brother, claimed that it was Rev. Stockton who intimated at Alvin Smith’s funeral that he had gone to hell. See Dan Vogel, “Introduction to Palmyra and Manchester, New York Documents,” in Early Mormon Documents (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1999), 2:5. A Presbyterian Church was also organized in Farmington, which formerly included Manchester, in 1817. By 1825 the congregation totaled eighteen members. Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western Palmyra, 378–79.

[18] Lorenzo Saunders, interviewed by William H. Kelley, 17 September 1884, 1–18, E. L. Kelley Papers, Community of Christ Library and Archives, Independence, Missouri, as cited in John Matzko, “The Encounter of the Young Joseph Smith with Presbyterianism,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 40, no. 3 (2007): 70. See also Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents, 2:127.

[19] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 133.

[20] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 139.

[21] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 478.

[22] Marsden, Evangelical Mind, 23.

[23] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 164–65.

[24] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 164–65.

[25] See John A. Wigger, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 184. Women also raised money to support the various missionary societies and their efforts through establishing “female cent societies.” Nichols, Presbyterianism in New York State, 93.

[26] See Bennet Tyler, Memoirs of the Life and Character of Rev. Asahel Nettleton, D.D., 5th ed. (Boston: Doctrinal Tract and Book Society, 1853), 91.

[27] Rev. Asahel Nettleton to Rev. Mr. Aikin of Utica, 13 January 1827, in Letters of the Rev. Dr. Beecher and Rev. Mr. Nettleton on the New Measures in Conducting Revivals of Religion. Beecher, Lyman, Nettleton, Asahel. January 1, 1828, 18.

[28] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 172.

[29] See Edison Gary Cheek Jr., “Revivalism: A Study of Asahel Nettleton” (master’s thesis, Dallas Theological Seminary, 1979).

[30] Sung Ho Kang, “The Evangelistic Preaching of Asahel Nettleton and Charles G. Finney in the Second Great Awakening” (PhD diss., Southwest Baptist Theological Seminary, 2004), 30–31.

[31] Tyler, Memoirs, 156.

[32] Tyler, Memoirs, 106.

[33] Rev. Asahel Nettleton to Rev. Dr. Spring, of New York, 4 May 1827, in Letters of the Rev. Dr. Beecher and Rev. Mr. Nettleton, 10.

[34] Rev. Asahel Nettleton to Rev. Mr. Aikin of Utica, 13 January 1827, in Letters of the Rev. Dr. Beecher and Rev. Mr. Nettleton, 10.

[35] Tyler, Memoirs, 172.

[36] “Extracts from a letter from the Rev. Henry Axtell, Geneva, N. Y., 18 October 1819,” Christian Spectator, 475.

[37] “Extracts from a letter, dated Union College, Schenectady, 28 April 1820, to a friend in Connecticut,” Religious Intelligencer 4 (June 1819–May 1820): 812.

[38] What Hath God Wrought? A Narrative of the Revival of Religion, within the Bounds of the Presbytery of Albany in the Year 1820 (Philadelphia: S. Probasco, 1821), 6–10, 22.

[39] Milton V. Backman Jr., “Awakenings in the Burned-Over District: New Light on the Historical Setting of the First Vision,” BYU Studies 9, no. 3 (1968/

[40] What Hath God Wrought?, 17.

[41] Slavery was not abolished in the state of New York until 1827.

[42] What Hath God Wrought?, 23.

[43] “Extract of a letter from the Rev. Asahel Nettleton, to a gentleman in Boston, dated Nassau, May 8, 1820,” Palmyra Register, 7 June 1820. “My dear brother, we live in an interesting time—This is that which was spoken of by the prophet Joel.”

[44] “Extracts from a Narrative of the Revival of Religion, within the Bounds of the Presbytery of Albany, Published by Order of the Presbytery,” Christian Spectator, 1 May 1821, 269.

[45] R. S. Smith, Recollections of Nettleton and the Great Revival of 1820 (Albany: E. H. Pease, 1848), 33–34.

[46] For much more on how youth responded to the spirit of revivalism, see Richard D. Shiels, “The Scope of the Second Great Awakening: Andover, Massachusetts, as a Case Study,” Journal of the Early Republic 5, no. 2 (1985): 223–46.

[47] Nancy F. Cott, “Young Women in the Second Great Awakening in New England,” Feminist Studies 3, no. ½ (1975): 15–29. Perhaps as high as three-fifths of the converts in the New England revivals between 1798 and 1826 were female.

[48] Letter from Ariel Kendrick to the editors, January 1820, in American Baptist Magazine 2, no. 8 (March 1820): 297.

[49] Letter from L. W. B., 7 April 1820, to Rev. Dr. Baldwin, in American Baptist Magazine 2, no. 9 (May 1820): 343. For a fine treatment of the role of youth in the Second Great Awakening, see Trevor J. Wright, “Your Sons and Your Daughters Shall Prophesy . . . Your Young Men Shall See Visions: The Role of Youth in the Second Great Awakening, 1800–1850” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2013). Wright demonstrates both qualitatively and quantitatively that youth were not merely passive onlookers in these religious revivals but were very active participants. Wright, “Your Sons and Your Daughters Shall Prophesy,” 147–50.

[50] Letter from R. Maddocks to the editors, American Baptist Magazine 2, no. 11 (September 1820): 407.

[51] Hotchkin, History of the Purchase and Settlement of Western New York, 163.

[52] Thomas Chalmers, Sermons Preached in the Iron Church, Glasgow (Printed for Chalmers and Collins, 1823), 68.

[53] Letter from Miss Eliza Higgins, 30 October 1820, Methodist Magazine (August 1822): 291. For much more on the important role women played in the conversion process during these times, see Rachel Cope, “‘In Some Places a Few Drops and Other Places a Plentiful Shower’: The Religious Impact of Revivalism on Early Nineteenth-Century New York Women” (PhD diss., Syracuse University, 2009).