Kent P. Jackson, “'O Lord, What Church Shall I Join?': The Question and the Answer,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 205‒18.

Kent P. Jackson is a professor emeritus of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

The First Vision has many contexts, some of which include the religious environment in which Joseph Smith lived in western New York early in the nineteenth century, the movements and trends within the Christianity of his time, the dynamics of his family, and the political and social realities of the early United States. One context that must not be overlooked is the context within the broad spread of Christian history from the days of Jesus and his apostles to Joseph Smith’s own time. This chapter will examine how the First Vision responds to that context in profound ways.

We have five accounts of the First Vision preserved in the Prophet’s own words.[1] Each account is different from the others, and each makes unique contributions. They were written at different times in the Prophet’s life and reflect the different concerns he had at the time they were related. They also reflect different audiences that he had in mind. All of them, nonetheless, are grounded in the issue that motivated his quest for revelation—a desire to know where, in a world of competing Christian churches, he could find religion that was approved by God. On that topic, all the accounts present the same message.

The Question

When recounting the story in 1832, Joseph Smith gave words to the impression he felt that Christianity had gone astray. He wrote that the world “had apostatized from the true and living faith, and there was no society or denomination that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament.”[2] Three years later he stated that he did not know at the time “who was right or who was wrong” among the different manifestations of Christianity, and he believed that it would be of great importance to be “right in matters that involve eternal consequences.”[3] In his 1842 account he wrote that he had observed “a great clash in religious sentiment” that left him wondering which, if any, of the churches was in tune with God’s will.[4] In each of those accounts Joseph Smith reported that his desire to know led him to pray in order to obtain the answer from God.

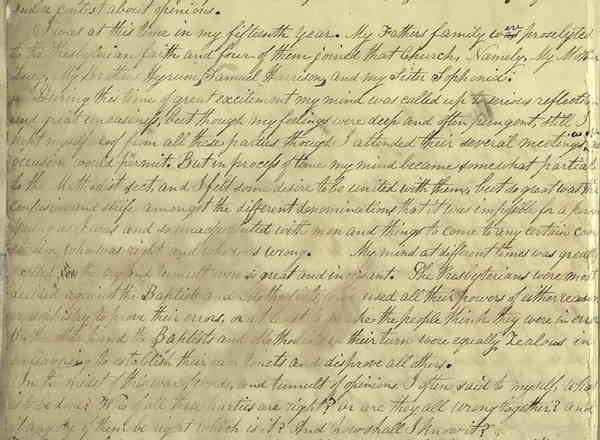

In Joseph Smith's 1838 narrative that is now the Pearl of Great Price, he wrote that he wanted to know "who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?" Joseph Smith Papers.

In Joseph Smith's 1838 narrative that is now the Pearl of Great Price, he wrote that he wanted to know "who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?" Joseph Smith Papers.

In the Prophet’s reports of the First Vision recorded in 1832, 1835, and 1842, he set forth the issue—religious confusion and a desire to know where to find God’s truth, but he did not record the question he asked in his prayer. As reported by a journalist in 1843, however, the Prophet asked this question: “O Lord, what church shall I join?”[5] And in his 1838 narrative that is now in the Pearl of Great Price, the Prophet wrote that he wanted to know “who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?” Motivated by biblical invitations to seek wisdom through prayer, he decided to “ask of God,” and when he told of the appearance of the Father and the Son to him, he wrote: “I asked the Personages who stood above me in the light, which of all the sects was right . . . and which I should join” (Joseph Smith—History 1:10, 13, 18).[6]

We often look at historical events from the perspective of later generations and the impact those events had on subsequent developments that we collectively call “history.” Thus we are not wrong to see Joseph Smith’s request for wisdom as the world-changing event that it truly was. But for a fourteen-year-old boy, his prayer was not the start of the restoration of the gospel, the beginning of a new gospel dispensation, or the first step in preparing the world for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. It was a straightforward petition from a humble young man who simply wanted to know, in an environment of religious diversity and confusion, “What church shall I join?”

The Answer

In his retellings of the First Vision, Joseph Smith chose different ways to convey what he had learned in answer to his prayer. The answer was actually very straightforward. He reported that the two divine beings who appeared to him told him that none of the churches was “acknowledged of God as his church and kingdom.” He was “expressly commanded” to “go not after them” and received a promise that “the fulness of the gospel should at some future time be made known” to him.[7] His 1838 account makes his instructions very clear: “I was answered that I must join none of them” (Joseph Smith—History 1:19).[8] The reason was explained at the same time. He was told that “all religious denominations were believing in incorrect doctrines.”[9] “They were all wrong,” and “all their creeds were an abomination” in God’s sight. Their professors taught “the commandments of men, having a form of godliness, but they [denied] the power thereof” (Joseph Smith—History 1:19).

Based on Joseph Smith’s statements in his recorded accounts, Jesus’s message can be seen as having four points of emphasis. The first was that the world was in a state of wickedness. The second and third were that there was no divinely acknowledged church on the earth and that Joseph Smith was thus to join none of the existing churches. The fourth point was that “at some future time” the “fullness of the gospel” would be made known to him. The historical record shows that Joseph Smith was cautious about speaking of the First Vision, especially in the early days of the Restoration, and the vision was not emphasized as a source of theology until after his death.[10] But one part of its message—the absence of a divinely recognized church and the role of Joseph Smith in restoring God’s truth—was central to the Latter-day Saint narrative from the beginning. That message had its beginning in the First Vision, and it remained central in Joseph Smith’s revelations.

The Latter-day Saint belief in an apostasy of early Christianity is not the result of bigotry against other Christian denominations nor of an incorrect understanding of history. At the core of this belief are the words of Jesus Christ as quoted by the Prophet Joseph Smith. As we look at those words, however, it is important that we understand them, know what they mean, and learn what they tell us about historical events. We recognize, for example, that the Lord’s chastisement was not directed at honorable individuals who had been led into confusion by the wrong ideas of others, but the rebuke was aimed at false teachings, those who perpetrated those teachings, and those who did not live according to what they taught.

Jesus said that the churches were “all wrong,” a phrase with grammatical ambiguity that requires our attention. Was he saying that they were entirely wrong or that all of them were wrong? Stated differently, does the word all modify wrong, or does it modify they? The answer is clear: of course the churches were not entirely wrong, because most were teaching basic beliefs that were confirmed by the Restoration. The fact that the Prophet was told that “the fullness of the gospel” would be made known later makes it clear that although the fullness was not then on earth, the gospel—or some considerable part of the gospel—was already present. Indeed, countless Christians in Joseph Smith’s day had embraced the Christian gospel and lived by it. Consider what are called the gospel’s “first principles and ordinances”: Many thousands exercised “faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.” They believed in and practiced “repentance,” many accepted baptism “for the remission of sins,” and many believed in and desired to receive the Holy Ghost (Articles of Faith 1:4). The scriptures reserve the phrase “fulness of the gospel” exclusively for what the Restoration brought into the world,[11] but countless Christians already lived their lives in accordance with gospel principles. The Restoration gave to Christianity what was necessary to make it whole, including not only the truths, clarifications, and understandings that came through modern revelation but more particularly the Church organization and the priesthood through which ordinances are performed that are recognized by God and have binding power. Because all churches in Joseph Smith’s day were lacking those Restoration gifts—not only in the Palmyra-Manchester area but everywhere—all of them, to some degree, were “wrong.”

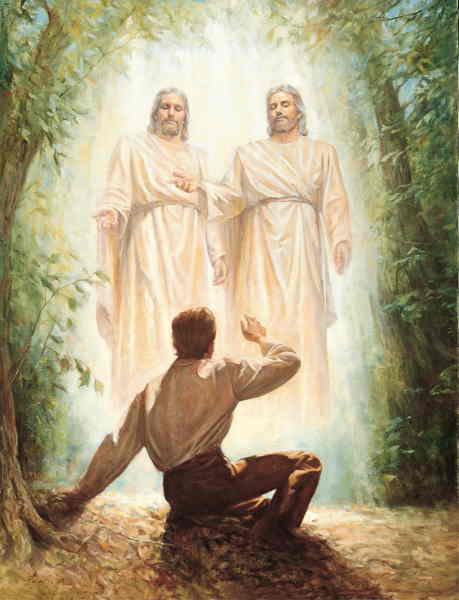

The First Vision was a dramatic validation of Christianity. But with its doctrinal focus on the nature of God and Jesus, the First Vision shows that Christianity in Joseph Smith's day was not the pristine Christianity of the early Church but was a Christianity in need of restoration. First Vision, by Del Parson. © 1987 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The First Vision was a dramatic validation of Christianity. But with its doctrinal focus on the nature of God and Jesus, the First Vision shows that Christianity in Joseph Smith's day was not the pristine Christianity of the early Church but was a Christianity in need of restoration. First Vision, by Del Parson. © 1987 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Latter-day Saints sometimes use the term the Apostasy to refer both to the forces that overpowered the early Christian Church and to the condition of the world from the end of the early Church to the present. It is important to distinguish between the two. Second Thessalonians 2:3 is invoked frequently for scriptural justification for belief in the Apostasy. Paul wrote that the Second Coming of Jesus would not take place “except there come a falling away first.” This translation, however, is both inadequate and misleading. The Greek word translated here as “falling away” is apostasía, from which we derive the modern English word apostasy. The idea of “falling away,” which suggests a gradual drifting to modern readers, is not one of apostasía’s meanings and has led some Latter-day Saints to misinterpret what happened to the early Church. The word apostasía is used in ancient Greek sources to mean “revolt,” “rebellion,” and “revolution,” clearly suggesting a conscious effort to overthrow established institutions and authority. Additionally, in the Greek New Testament, apostasía is preceded by a definite article, the, which is mistranslated in the King James Bible as a, the indefinite article. “The revolution,” or “the rebellion,” is what Paul’s words anticipated, and the definite article used with the term suggests that his readers may have already heard of it and had previously been warned.[12]

This understanding is consistent with prophecies of apostasy in the New Testament, which foretell a time when Church members would reject the authority and teachings of the apostles and replace them with others of their own choosing. And, this understanding is also consistent with passages in the New Testament itself that describe the rejection of the apostles and their teachings as it happened.[13]

These texts lead to the inevitable conclusion that the Apostasy of the Church led by Jesus and his apostles was early and that it took place while apostles were still alive and while the New Testament was being written. Jesus knew that he was going to be killed but made provision for the Church to carry on after him. That provision was the institution of his twelve apostles, who received from him the keys of the kingdom and were instructed by him about how to carry on his work after his death. Luke, author of Acts and chronicler of the early Church, reported how the works of Jesus continued in the hands of the Twelve after he left them. It is not unimportant that the first item of business after Jesus’s departure was to call a new apostle, Matthias, to replace Judas, clearly indicating that the apostleship was to continue in the Church. Later we know of three others who were called: James the brother of Jesus (Acts 12:17; Galatians 1:19), Barnabas (Acts 14:14), and Paul (Acts 14:14). Those three were called before AD 50, before even a quarter century had passed since the departure of Jesus. After those three we have no record in the scriptures, or anywhere else in ancient sources, of other apostles being called.

This timeline is significant because there is no description in the New Testament for the continuance of the Church of Jesus Christ without apostles. Nothing in Jesus’s words nor in scriptural history makes provision for the Church to even exist without them. Thus when God ceased calling new apostles because of rebellion in the Church, the apostleship was on the road to dying out. The last apostle left the scene in about AD 100. Thereafter Christian writers told of the apostles only in the past tense.[14] Though undoubtedly many good Christians remained and lived lives consistent with the gospel as they knew it—as many have done to the present time—the keys of the priesthood were gone, and the Christianity that remained did not include Jesus’s authorized Church. Later developments in Christian beliefs, some of which are very troubling, did not constitute the Apostasy but were consequences of the Apostasy.

Apostasy, including the Apostasy, is necessarily an “inside job” brought about by people within a movement. The apostasy that ended the early Church was not the result of persecution or lack of communication but was the result of a conscious choice on the part of far too many within the Church to reject the doctrines and authority of the apostles. Apostasy unfailingly includes the embracing of cultural influences that are contrary to the religion’s true principles, whether those influences are behavioral or doctrinal. And, as often then as now, apostasy leads to a shift in emphasis from divinely authorized prophets and apostles to self-appointed intellectuals. All of that is well documented in the history of the early Church and in the history of Christianity in the centuries that followed it. The demise of the Church was one thing, and its evolution into what Christianity became thereafter is another. Both needed the Restoration.

After the end of the early Church, several authors explained Christian beliefs as they understood them. Their preserved writings show that they were heavily influenced by the philosophical trends of their day, and in each generation they introduced new teachings that took Christianity even farther away from its revealed roots. Beginning in the fourth century, conflicts within Christianity motivated political and ecclesiastical leaders to convene what are called ecumenical councils—gatherings of bishops and civil leaders with the intent of establishing official doctrine. Together, the teachings of influential writers and the creeds formulated and announced by the councils became the foundations of traditional Christianity, and they have remained so to the present day.[15]

The Apostasy and the First Vision

The First Vision announced the beginning of the Restoration, but the vision actually did much more than that. By itself, it was a significant part of the Restoration because through it fundamental truths about God were revealed that had been lost from the world for many years. As a revelation of doctrine, the event of the First Vision—even independent of the words spoken in it—is as great as any of the texts we have in the Doctrine and Covenants.

The First Vision teaches that humans are created in the image of God. This truth is taught in Genesis and is evident in other biblical passages, but it was rejected by early Christian theologians because it clashed so fundamentally with the prevailing philosophies of the time. Even prior to the days of Jesus, Jewish thinkers under the influence of Greek philosophy had rejected the possibility not only of a bodily God but also of a God with definable or describable attributes. Christians later did the same.[16] The Jewish writer Philo of Alexandria (ca. 15 BC to AD 50) allegorized the passages in the Old Testament in which God is described in anthropomorphic terms and recast him in terms that were consistent with the philosophy of Plato and his successors.[17] Clement of Alexandria (AD 150–215), an influential Christian thinker, followed Philo’s lead and did the same with the God of the New Testament. Jesus, Clement taught, was entirely immune to emotions, “inaccessible to any movement of feeling—either pleasure or pain.”[18] How could Jesus be understood otherwise, given the prevailing philosophical view that ruled out a deity with humanlike characteristics? Clement’s student Origen (AD 185–254), a writer of long commentaries on biblical texts, was even more well versed in philosophy than his predecessors because he had also studied under Ammonius Saccas, one of the founders of the philosophy called Neoplatonism. When it came to subjects like the physical reality of God, Origen employed what he called a “spiritual exegesis” that allowed him to view as only metaphor any biblical words he chose not to take literally.[19] Other writers in turn, most notably Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430), added to the corruption of the pure Christian faith by further drawing it away from its revealed roots. Augustine taught the idea of the depravity of humans, viewed sexual relations as the means by which God’s children became sinful at birth, and introduced the idea of predestination into mainstream Christianity.[20]

By Joseph Smith’s day the unknowable God of Greek philosophy had been the God of Christian intellectuals and the official God of their churches for a millennium and a half. While we cannot say whether Joseph Smith understood from the First Vision that God has a body of flesh and bones, it can be stated that he learned then that God and humans are in the same form.[21]

The First Vision also reveals that God and Jesus Christ are two separate individuals with distinct personal identities. The New Testament clearly teaches this truth, but early Christian writers, followed by the ecumenical councils, rejected it. Under the influence of Greek thought, they devised in its place the nonscriptural trinitarian mystery that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are three persons within one being. This has been the official theology of the Christian world since the fourth century AD, and it continues to be at the very foundation of Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant Christianity. The First Vision proves it to be wrong and shows instead the separate identities of the Father and the Son. (As an aside, it is interesting that for many of Joseph Smith’s contemporaries the separateness of God and Jesus was not a new teaching. In that day of remarkable scriptural literacy among many ordinary Christians, belief that the Father and the Son were humanlike in form and that they were separate beings was not uncommon among those who acquired their views from reading the Bible directly.)

The First Vision reveals truths about the relationship between the Father and the Son. Jesus is divine, but he is subordinate to the Father. Early councils, arguing from the idea of the trinity, rejected this idea. In the First Vision the Father appeared first, followed by the Son.[22] The Father introduced and bore testimony of the Son (see Joseph Smith—History 1:17),[23] and the Son then delivered the message to Joseph Smith.[24] While these matters are only briefly mentioned in the Prophet’s accounts and are not discussed, they show the pattern that we see elsewhere: God the Father presides, and Jesus Christ, God’s Son, speaks in the name of and with the authority of the Father and is the divine voice in modern revelation.

Authority and the First Vision

The First Vision verified the belief of millions of Christians in Joseph Smith’s day that God lives, that Jesus is the Christ and the Savior of the world, and that the New Testament message about them is true. God did not appear to Joseph Smith to acknowledge the truth of other religions, but he appeared to substantiate and restore the religion of the New Testament. The First Vision was a dramatic validation of Christianity. But with its doctrinal focus on the nature of God and Jesus, the First Vision shows that Christianity in Joseph Smith’s day was not the pristine Christianity of the early Church but was a Christianity in need of restoration. The first task in that process, undertaken by the First Vision itself, was to undo the philosophical framework that had been built around Christianity in the postapostolic period by the early councils and creeds. It would be a new day in the history of God’s dealings with his children on the earth.

Finally, the First Vision is a statement of authority. It exposes all the historical developments since the days of the apostles as unauthoritative. Jesus told Joseph Smith that the creeds were “an abomination” to him (Joseph Smith—History 1:19), but we are left to wonder if the word creed here represents the formal statements of the ancient councils or Christian belief systems more generally.[25] In either case, the First Vision shows that the authority to receive revelation from God, announce correct doctrine, and establish a divinely recognized church did not belong to any Christian denomination then existing but would now again be in divinely appointed hands. Thus in answer to the question, “What church shall I join?” the message was clear: “Don’t join any of them.”[26] The young prophet was told that the fullness of the gospel would someday be made known to him, but he did not report whether he was informed at that time of his own role in the process. Three years later when Moroni appeared to the Prophet, his role in the Restoration was made more clear. Moroni told him that “God had a work for [him] to do” (Joseph Smith—History 1:33) and that “[he] was chosen to be an instrument in the hands of God to bring about some of his purposes in this glorious dispensation.”[27] The restoration of that work and the accomplishment of those divine purposes began with the First Vision.

Notes

[1] (1) A history Joseph Smith wrote in 1832: History, circa Summer 1832, https://

[2] History, circa Summer 1832, p. 2. In all documentary sources quoted, the spelling, punctuation, and capitalization have been standardized.

[3] Journal, 1835–1836, p. 23.

[4] “Church History,” 1 March 1842, 706.

[5] Interview, 21 August 1843, extract, p. [3].

[6] The Prophet mentioned that Matthew 7:7 and James 1:5 were New Testament passages that gave him confidence to seek revelation from God. See Journal, 1835–1836, p. 23; Joseph Smith—History 1:11–12.

[7] “Church History,” 1 March 1842, 707.

[8] The 1835 account does not record an answer regarding which church to join.

[9] “Church History,” 1 March 1842, 707.

[10] See Steven C. Harper, “Raising the Stakes: How Joseph Smith’s First Vision Became All or Nothing,” BYU Studies Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2020): 23–36.

[11] See 1 Nephi 10:14; 13:24–26; 15:13; 3 Nephi 16:10, 12; 20:28, 30; Doctrine and Covenants 1:23; 14:10; 20:9; 27:5; 35:12, 17; 39:11, 18; 42:12; 45:28; 66:2; 76:14; 90:11; 109:65; 118:4; 133:57.

[12] In each of these bibles—the English Standard Version (ESV), the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), and Today’s New International Version (TNIV)—the translation at 2 Thessalonians 2:3 reads “the rebellion.” The New Jerusalem Bible (NJB) uses “the Great Revolt.”

[13] The biblical evidence is explored in Kent P. Jackson, “Watch and Remember: The New Testament and the Great Apostasy,” in By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 1:81–117.

[14] That apostles existed only in the past is explicit or implied in the following early sources: 1 Clement 42.1–3; 44.3; Hermas 94.1; 102.2; Ignatius, To the Ephesians 3.2; 6.1; To the Magnesians 13.1–2; To the Smyrneans 8.1; To the Trallians 2.1–2.

[15] An explanation of these developments is found in Kent P. Jackson, From Apostasy to Restoration (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 19–56.

[16] See M. Catherine Thomas, “The Influence of Asceticism on the Rise of Text, Doctrine, and Practice in the First Two Christian Centuries” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1989).

[17] See, for example, Philo, On the Creation 69, 134–35.

[18] Clement, Stromata (Miscellanies) 6.9; A. Roberts and J. Donaldson, ed., The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, repr. 1951), 2:496.

[19] For example, in Origen, On First Principles.

[20] See Augustine, On the Predestination of the Saints, 1–43; and Kenneth M. Wilson, The Foundation of Augustinian-Calvinism (n.p.: Regula Fidei, 2019).

[21] See John W. Welch, “When Did Joseph Smith Know the Father and the Son Have ‘Tangible’ Bodies?,” BYU Studies Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2020): 299–310.

[22] See Journal, 1835–1836, p. 24; Interview, 21 August 1843, extract, p. [3].

[23] See also Interview, 21 August 1843, extract, p. [3].

[24] See History, circa Summer 1832, p. 3; Interview, 21 August 1843, extract, p. [3].

[25] This question is explored in Robert L. Millet, “Reflections on Apostasy and Restoration,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 27–32.

[26] Interview, 21 August 1843, extract, p. [3].

[27] “Church History,” 1 March 1842, 707.