The "Nature" of Revelation

The Influence of the Natural Environment on Joseph Smith's Revelatory Experiences

Matthew C. Godfrey

Matthew C. Godfrey, “The 'Nature' of Revelation: The Influence of the Natural Environment on Joseph Smith's Revelatory Experiences,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 149‒66.

Matthew C. Godfrey is a general editor and the managing historian of the Joseph Smith Papers in the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The natural world was something that brought Joseph Smith closer to God and facilitated his reception of revelation. Natural surroundings led to questions that revelations answered, while also providing Joseph Smith with proof of God’s existence and helping him achieve a mindset where he could commune with God. In addition, nature became the backdrop for visions and spiritual impressions that were less uplifting and more instructive regarding danger or unease in the world. At other times, pondering the natural environment allowed Joseph Smith to receive inspiration about both the history and the potential of an area. Joseph Smith’s revelations could thus be spurred by the environment while also affecting how Smith and others regarded nature.

Of course, not all revelations that Smith received came in natural settings. A majority came in the built environment: homes, offices, and the Kirtland Temple, for example. However, in these cases, revelatory experiences were not spurred by the buildings themselves; Smith was not contemplating a structure before communing with God. Yet his spiritual experiences in the natural world came precisely because Smith was thinking about and examining God’s creations, such as a landscape and its temporal and spiritual potential. Revelations that came in nature also provided more knowledge about the environment itself: the location of Zion and the productiveness of its land, for example, or the history and potential of an area. Examining three major events in Joseph Smith’s life—the First Vision, his summer 1831 trip to Missouri, and the Camp of Israel, or Zion’s Camp, expedition of 1834—highlights how nature and the environment could affect and shape Joseph Smith’s revelatory experiences, and how, in turn, these experiences either reflected or influenced Smith’s views of nature itself.

The First Vision

Joseph Smith’s First Vision occurred at a time when there was tension in how religion perceived the natural world. For many, different aspects of nature served as a testimony that God existed. For others, spending time in one’s natural surroundings was conducive to feeling God’s presence. This line of thought developed in part because of examples in the Bible. Several biblical accounts highlighted the ways that nature generated revelation and communion with God. Moses, for example, had several encounters with the divine in the natural world, including seeing “the angel of the Lord,” hearing God’s voice in a burning bush, and talking to God on a mountain (Exodus 3:2–4; 19:3). Elijah experienced God’s “still small voice” after a great wind, an earthquake, and a fire (1 Kings 19:11–12). Jesus was transfigured on a “high mountain,” where God’s voice was heard, and wrought out his suffering for humankind’s sins in a garden on the Mount of Olives (Mark 9:2–9; Luke 22:39–46).

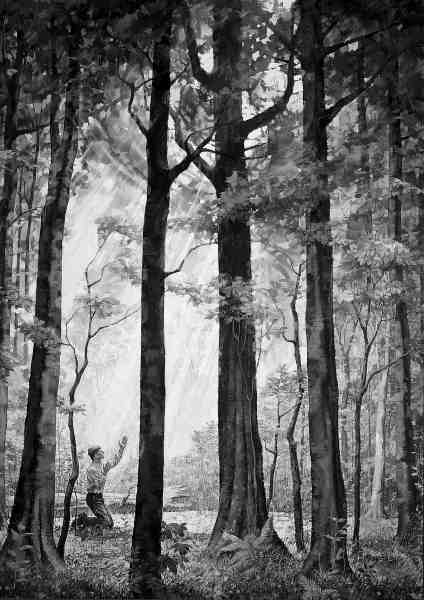

The First Vision, by Kenneth Riley. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The First Vision, by Kenneth Riley. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

New England’s Calvinist heritage was also steeped in the idea that God could be found in nature. John Calvin pointed to nature as evidence of God’s existence, stating that “all creatures, from those in the firmament to those which are in the center of the earth,” testified that God was real. “The little birds that sing, sing of God; the beasts clamor for him; the elements dread him, the mountains echo him, the fountains and flowing waters cast their glances at him, and the grass and flowers laugh before him,” Calvin declared.[1]

Jonathan Edwards, a renowned Congregationalist preacher in the eighteenth century, also perceived God in the natural world. To Edwards, the Lord appeared everywhere, “in the sun, moon and stars; in the clouds, and blue sky; in the grass, flowers, trees; in the water, and all nature.” Edwards stated that he “used to sit and view the moon, for a long time; and so in the daytime, spent much time in viewing the clouds and sky, to behold the sweet glory of God in these things.”[2]

Many of Joseph Smith’s contemporaries also experienced God in their natural surroundings, whether at camp revivals or in more solitary encounters outdoors. For example, in the late eighteenth century, Benjamin Abbott, on his way to a Methodist meeting, went into the woods to pray to God “for mercy,” while Enoch Edwards, a Baptist, “retired to a grove of woods to pray” because of his “spiritual pain.” Noted preacher Charles Grandison Finney decided in 1821 that the place to “give [his] heart to God” was in a forest.[3] Even Joseph Smith’s mother—Lucy Mack Smith—ventured into the woods for spiritual relief. Sometime in the late 1790s or early 1800s, Lucy, disturbed at her husband’s lack of enthusiasm for organized religion and hurt that he had urged her to stop attending Methodist meetings, went “to a grove of handsome wild cherry trees and prayed to the Lord that he would so influence the heart” of Joseph Smith Sr. that one day he would “rec[ei]ve the Gospel whenever it was preached.” According to Lucy, she spent a considerable amount of time in the grove, pouring her heart out to God.[4] Such an example, if told to her family, would have influenced Joseph Smith to seek his own spiritual enlightenment in a forest.

Yet there was another prevalent religious belief at the time, one that was not as friendly to nature, especially to uncultivated wilderness. Also stemming from Puritan thought, this view held that the wilderness was “a cursed and chaotic wasteland” and “a moral vacuum” where evil and temptation existed. To drive that evil away, humans had to cultivate the land and make it productive through agriculture. Planting seeds and raising crops would redeem the evil wasteland, birthing it into a pristine and Edenic condition.[5] If such action were not taken, then the devil would maintain possession over the unredeemed land. For example, William Glendinning, a Methodist circuit preacher in the 1700s, had an almost daily battle with Satan on a piece of ground close by a creek until he commanded Satan to depart. Thereafter, the devil left Glendinning alone.[6] Likewise, if settlers took action by planting seeds, they could figuratively force Satan from the wilderness.

When Joseph Smith went into the Sacred Grove in 1820, these two schools of thought about nature were still prevalent. Eventually, through the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and others, the view of nature as a place for communion with deity would win out,[7] but in 1820 in rural New York, the Puritan traditions of forests as both good and bad still battled. The conflict between the two can be seen in Joseph Smith’s experience in a grove of trees in 1820.

Those familiar with the story know that Smith, having pondered about his spiritual standing and the doctrine of different churches, went into a forest close by his house in the early spring of 1820. There, he prayed and experienced a vision of God the Father and Jesus Christ. Although this general outline is well known to Latter-day Saints, the role that Smith believed nature played in preparing him for the vision has been less appreciated. In his first written account of the vision, Smith—much like Calvin and Edwards—acknowledged that the natural world was instrumental in his feeling comfortable approaching God in prayer. “I looked upon the sun, the glorious luminary of the earth, and also the moon, rolling in their majesty through the heavens,” Smith remembered, and they, together with “the stars shining in their courses,” convinced him that God existed. Equally important was his perception of “the beasts of the field, and the fowls of heaven, and the fish of the waters.” All of these creations, as well as “[humans] walking forth upon the face of the earth in majesty and in the strength of beauty,” testified to Smith that there was “an omnipotent and omnipresent power, a being who maketh laws and decreeth and bindeth all things in their bounds, who filleth eternity, who was and is and will be from all eternity to eternity.” Smith’s perception of God in the natural world—a practice one scholar has called “natural contemplation”—enabled him to approach God “for mercy,” believing that “there was none else to whom [he] could go and obtain mercy.” He thus went into “the wilderness” to commune with God.[8]

But before Smith’s glorious vision on that spring day, he experienced a malevolent force—the evil that contemporaries believed existed because of the uncultivated state of the forest. According to Smith, after he began his prayer, he found that his tongue was bound and he could not speak. He heard a noise behind him, “like some person walking towards me,” but could not see anyone.[9] The evil presence grew stronger and was not confined to just a feeling of darkness; according to one account, the evil “filled [Smith’s] mind with doubts and brought to mind all manner of inappropriate images.”[10] “Thick darkness gathered around me,” Smith recalled, “and it seemed to me for a time as if I were doomed to sudden destruction.” At the moment when he felt the darkness would overwhelm him and that he would be destroyed by “the power of some actual being from the unseen world” (Joseph Smith—History 1:15–16), he called upon God and found himself freed from the influence, whereupon his vision of God and Jesus Christ occurred.

Smith’s experience highlights the divergent views about nature at the time. On the one hand, he encountered a dark presence in the wilderness, but on the other, he found God and Jesus Christ there. This was a clear battle between light and darkness—between Jesus Christ, who stated he was “the light of the world,” and Satan, characterized by Paul as one of the “rulers of the darkness” (John 8:12; Ephesians 6:11–12). In some ways, what Smith experienced followed a pattern that Americans pursued when encountering the wilderness. If people could cut down the trees and let the light come in, seeds could be sown, crops could be cultivated, and the wilderness would be redeemed. Naturally speaking, the light of the sun would conquer the darkness of the forest. In Joseph Smith’s case, he metaphorically conquered the darkness he felt in the grove through prayer, thereby allowing light to come in and seeds of redemption to be planted in his spirit. As Smith would later be told in a revelation, knowledge and intelligence are light.[11]

Influenced by this experience, Smith again found redemption and forgiveness in a grove of trees in Greenville, Indiana, twelve years later. Without experiencing the darkness of his 1820 encounter, he poured out his soul to God and felt again God’s mercy and forgiveness.[12] Clearly, Joseph Smith could feel close to God and hear his voice in groves and forests, even if, at times, he had to conquer evil before the divine presence could be felt.

1831 Zion Revelations

In 1831 nature was instrumental in helping Joseph Smith receive God’s word and will about the physical location of the city of Zion. For Smith and early members of the Church, a key component leading to the second advent of Jesus Christ was the establishment of a “New Jerusalem,” or City of Zion, on the American continent (Articles of Faith 1:10). The Book of Mormon contained prophecies of this New Jerusalem, as did some of Joseph Smith’s revelations.[13] By 1831 Church members waited eagerly to hear where God wanted the city of Zion established. A June 1831 revelation directed Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon to travel to the state of Missouri, where God would tell them the location of “the land of [their] inheritance.”[14] Smith and Rigdon followed this instruction and, together with a larger group of men and women, arrived in Jackson County, Missouri, in July 1831.[15]

After Joseph Smith reached Jackson County, he spent time thinking about the American Indian population living west of Missouri’s western border in what was then called Unorganized Territory. Part of the reason for Smith’s ruminations was the Book of Mormon’s assertion that a group known in the book as Lamanites—which the Saints at the time interpreted to mean American Indians—would be instrumental in the construction of the New Jerusalem. Therefore, according to a later history, Smith contemplated those natives who lived in the “wilderness” beyond Missouri’s border. After thinking about their condition and the land they lived on, Smith asked himself and God several questions, including, “When will the wilderness blossom as the rose; when will Zion be built up in her glory, and where will thy Temple stand unto which all nations shall come in the last days?”[16]

The notion of God making the wilderness blossom as a rose had biblical roots in the book of Isaiah, as well as more contemporary roots in the Puritan John Winthrop’s notions of establishing a city on a hill to serve as a spiritual light to a darkened world. It was also present in Joseph Smith’s revelations.[17] In December 1830, as part of his efforts to revise the Bible through inspiration, Smith received revelation that expanded the account of the biblical prophet Enoch to include a vision Enoch saw of the earth crying in pain because of the wickedness of its inhabitants. In this vision, the earth asks when it will be sanctified, and the Lord tells Enoch that the earth will rest at the time of the Savior’s return, when righteousness and truth would sweep the earth and gather out the Lord’s elect (see Moses 7:56–64). A few months later, Smith dictated a revelation that taught that before Jesus Christ’s Second Coming, “Jacob shall flourish in the wilderness & the Lamanit[e]s shall blossom as the rose.”[18] These all seemed to indicate that an important precursor to the Lord’s second advent was the redemption of the earth’s wildernesses through the establishment of and gathering to Zion, which would allow the earth to rest.

As Smith pondered the land and these questions, he received another revelation that presented God’s answers. In this revelation, God informed Smith of “the very spot upon which he designed to commence the work of the gathering, and the upbuilding of an holy city, which should be called Zion.”[19] This spot was in Jackson County, with the city of Independence as its center place.[20]

That a contemplation of the land and its native population spurred revelation on the location of the city of Zion should not be surprising. The New Jerusalem was both a spiritual doctrine and a physical location. Zion was inextricably tied to the land, a sacred place that was a key factor in the Saints’ millennialism. According to an earlier revelation in March 1831, the Saints would find refuge from the temporal and spiritual terrors that would precede Jesus Christ’s Second Coming in the physical space of Zion. It would be “a land of peace” and “a place of safety.”[21] Later, Smith would teach that possessing an inheritance—or parcel of land—in the New Jerusalem would be a sign to God of a Church member’s righteousness because it signified that an individual was willing to consecrate what they had to the Church—a requirement to receive an inheritance. Although Smith did not say so explicitly, it would seem, based on his earlier teachings, that the inheritance would tie someone to God more strongly if an individual had cultivated it and made it blossom as the rose.[22] Regardless, the revelation of where Zion would be situated came as Smith contemplated both its physical aspects and spiritual potential.

Just a couple of weeks after the revelation declaring the location of the city of Zion, other revelations instructed the Saints on how to deepen their spiritual connections with the land. In August 1831, Joseph Smith dictated revelations that explained the bounties that the land of the New Jerusalem had to offer if the Saints would obey God’s commandments.[23] These revelations came as Smith contemplated the rough, undeveloped frontier conditions of Jackson County. The area had been the homeland of the Osage, Kansas, and Missouri groups of American Indians until 1808 when the federal government entered a treaty with the Osage and Kansas that extinguished their title to the land. White settlement of the area began in earnest in 1826—just five years before Joseph Smith reached Jackson County.[24]

In 1831 the town of Independence was relatively undeveloped. One observer, for example, described it as containing only “two or three merchants stores, and fifteen or twenty dwelling houses.”[25] In 1832 Washington Irving traveled through the area and stated that conditions became “rougher and rougher” the closer he came to Independence. Charles Latrobe, who was traveling with Irving, described the town as “nothing but a ragged congeries of five or six rough log huts, two or three clapboard houses, [and] two or three so-called hotels, alias grogshops.”[26] For those who came from the more settled parts of the eastern United States, Jackson County and Independence lacked the amenities that they were accustomed to. As Church leader Edward Partridge told his wife Lydia, “We have to suffer & shall for some time many privations here.”[27]

The lack of development in Independence was disturbing to some of the elders of the Church who accompanied Joseph Smith to Missouri. One of these was Ezra Booth, who stated that he expected to find a burgeoning city and a thriving congregation of Church members in Independence. Discovering the opposite, Booth was disappointed.[28] This disillusionment was addressed in a revelation Smith dictated on 1 August 1831, “concerning this land unto which I [the Lord] have sent you [the Saints].” In addition to providing instructions about purchasing tracts of land in Jackson County, the revelation told the Saints that they could not “behold with [their] natural eyes for the present time the design of [their] God concerning those things which shall come hereafter & the glory which shall follow after much tribulation.” The revelation seemed to acknowledge the undeveloped nature of Jackson County, but it counseled the Saints to be patient because they could not yet see what the Lord had in store for the land.[29]

Another revelation dictated on 7 August provided additional guidance to the Saints about the potential of Jackson County and how Church members could obtain the abundance of nature. This revelation gave the Saints hope that, by their righteousness, they could transform the land of Zion from its undeveloped condition into a fruitful and productive paradise. The revelation directed Church members specifically to keep the Sabbath Day holy by cheerfully praying, offering sacraments, and resting from their labors. If they did, the revelation continued, God would bless them with “the fulness of the earth,” including “beasts of the fields & the fowls of the air & that which climbeth upon trees & walketh upon the earth yea & the herb & the good things which cometh of the earth whether for food or for raiment or for houses or for barns or for orchards or for gardens or for vineyards.”[30] The earth, and specifically Jackson County, would produce in abundance for the Saints if they were righteous, especially in their Sabbath Day observance. In this way, Church members could become spiritually tied to the land itself—a sacred counterpoint to their physical connection to the land through the purchase of inheritances.

It is important to note that these promises were made to the Saints because of Joseph Smith’s own encounters with the land in Jackson County. These revelations came while Smith was still in Independence and while he contemplated what the Saints needed to do to establish Zion there. As with the revelation designating Jackson County as the location of the New Jerusalem, the August revelations and their promises of an abundant earth came as Smith pondered the land and considered its potential.

Although both the July and August revelations brought pleasing news to Joseph Smith and the Saints about the bounties nature had in store for the city of Zion, the environment also spurred revelations and visions that served as warnings of the potential destruction nature could wreak. This was also part of Smith’s experiences in Missouri during the summer of 1831. In early August, Smith and several other men decided to return to Ohio in accordance with direction given in an 8 August 1831 revelation.[31] The group left Independence on 9 August and traveled down the Missouri River in canoes. Within a couple of days, contention developed, leading Oliver Cowdery to warn the men that problems awaited unless they repented. Not long after Cowdery’s declaration, the canoe in which Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon were riding almost capsized after being snagged on a sawyer—a submerged tree.[32] Sawyers were a prevalent pitfall on the Missouri River, constituting “the most formidable dangers to navigation of the river” and causing numerous steamboat wrecks. According to one source, “These snags were the terror of the [steamboat] pilot.”[33]

This encounter with nature apparently made both Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon uneasy, leading to a revelation on the destructive character of the Missouri River. According to Joseph Smith’s manuscript history, after Smith and Rigdon successfully made their way to the river’s shore at a location called McIlwaine’s Bend, William W. Phelps, one of the men with the group, experienced “an open vision, by daylight,” of “the Destroyer, in his most horrible power, rid[ing] upon the face of the waters.”[34] Thereafter, Joseph Smith dictated a revelation that, according to a heading made by John Whitmer, unveiled “some mysteries” about “the River Distruction (or Missorie).” This revelation declared that “many dangers” existed “upon the waters & more especially hereafter for I the Lord have decreed in mine anger many distructions upon the waters yea & especially upon these waters.” Those traveling back to Ohio were thus told to stop journeying down the river and to travel instead by land—an injunction that applied to anyone designated to move to Missouri to help build the city of Zion.[35]

The warnings these revelations made about the Missouri River influenced how the Saints perceived the waterway. Elizabeth Godkin Marsh, for example, stated that some of the men who had returned from Missouri told her that the Missouri River was “always rily and bubly and looks mad as if it had been cursed.”[36] William W. Phelps also reiterated to those thinking of traveling to Missouri to do so by land, thus avoiding “disasters upon the waters.”[37] In this instance, a natural waterbody generated revelation and inspiration for Joseph Smith and others, which in turn affected how the Saints perceived the body of water thereafter.

Camp of Israel (Zion’s Camp)

Three years later, when Joseph Smith led a group of men, women, and children from Ohio to Missouri in the Camp of Israel, or Zion’s Camp,expedition, the land again was the catalyst for revelation. In this instance, traversing areas with evidences of ancient civilizations prompted revelation explicating more about these civilizations. As the group crossed Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois on its way to Missouri in May and June 1834, Smith, observing the land around him, stated that the natural features he saw proved that the Book of Mormon was a legitimate history. Writing a letter to his wife, Emma, from the eastern banks of the Mississippi River in Illinois on 4 June 1834, Smith discussed “wandering over the plains of the Nephites [one of the groups depicted in the Book of Mormon], recounting occasionally the history of the Book of Mormon, roving over the mounds of that once beloved people of the Lord, picking up their skulls & their bones, as a proof of its divine authenticity.”[38]

What Smith told Emma seemed to be a reference to an incident that occurred the day before, when the Camp of Israel was traversing the vicinity of what is now Valley City, Illinois. This area contained numerous burial mounds of native North American groups. According to Heber C. Kimball, several members of the camp climbed to the top of one of the mounds—which has since been identified as a Hopewell burial mound from the Middle Woodland period of the pre-Columbian era—and saw human bones “strewn” across the ground. “This caused in us very peculiar feelings,” Kimball continued, which were heightened when the group dug up a skeleton that had apparently been pierced by an arrow. Later that day, Kimball explained, the group wanted “to know who the person was who had been killed by that arrow.” Reflecting on the mound, the skeleton, and the surrounding vicinity, Joseph Smith “enquired of the Lord and it was made known [to him] in a vision” that the individual was “an officer who fell in battle, in the last destruction among the Lamanites, and his name was Zelph.” Hearing this identification, the group “rejoice[d] much” because “God was mindful of [the group] as to show these things to his servant.”[39]

To readers today, the fact that members of the Camp of Israel desecrated the graves of native groups is likely disturbing. Nevertheless, the incident serves as an example of how Joseph Smith’s encounters with his natural surroundings spurred revelation and direction from God about those surroundings. As Smith and the Camp of Israel continued their journey, there were other points in which the terrain served as a conduit for inspiration. Nathan Tanner later recollected that at one point, Joseph Smith “had a vision” of “the country that we had travelled over, in a high state of cultivation.” In that vision, Smith saw “springs and wells and pools” spread over the area, as well as “the people that possessed” the land.[40] George A. Smith recalled another incident where the group “passed through a thicket of small Timber of recent growth.” Joseph Smith felt uneasy in the location, stating that the area made him “much depressed in spirits” because “there ha[d] been a great deal of bloodshed here at some time.” He elaborated that “when a man of God passes thro’ a place where much blood has been shed he will feel depressed in spirits and feel lonesome and uncomfortable.”[41] As in other locations, the environment could produce both uplifting and disheartening feelings, and it could also prompt revelation from God explaining more about the history of the region.

Conclusion

These experiences demonstrate that contemplations of nature and the environment helped trigger spiritual experiences in Joseph Smith, whether because they provided a quiet setting where God’s inspiration could more easily be heard and felt or because contemplating the state of an area helped Joseph Smith understand more readily its history, potential, and dangers. The physical landscape was important to Smith and the Saints for numerous reasons—Zion, for example, was a sacred location, and Smith sought direction pertaining to the physical development of that land. Likewise, the landscapes of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri spurred Joseph Smith to contemplate scenes from the Book of Mormon and to receive revelation pertaining to the ancient cultures depicted in that book. It is also significant that while nature could be a catalyst for Smith’s revelations, the Saints’ beliefs about natural features were influenced by the revelations he received. Thus, a frightening experience on the Missouri River could generate revelation about the river that then influenced Church members to see the river as a dangerous and cursed waterway.

It is also important to note that Joseph Smith’s views about nature were influenced by the cultural milieu in which he was raised. He could thus see a forest as both a place where God could be experienced and as a place where Satan could attack. He could see a river as both an important means of transportation and the habitat of the devil. And he could see the landscapes of the Midwest as both proof of the Book of Mormon and as places of uneasiness because of the bloodshed that had occurred in the area. These seemingly contradictory views of nature highlight the difficulties Americans as a whole experienced when they encountered the wild. Wilderness could provide areas to find God, but those areas were not seen as redeemed and Edenic until agricultural cultivation and civilization had been applied.

The interplay between nature and revelation is a relatively unexamined field in the history of the Latter-day Saints but is one that deserves more attention and analysis. Smith clearly had many spiritual experiences that did not come in the wild or from his contemplations of nature, but those that were influenced by the natural world were important for what they demonstrated about the duality of nature and what they taught about physical aspects of Zion and physical landmarks. The environment was an important revelatory conduit for Joseph Smith and the early Saints, and it affected some of Smith’s key spiritual experiences.

Notes

[1] John Calvin, as cited in Mark R. Stoll, Inherit the Holy Mountain: Religion and the Rise of American Environmentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 21–22.

[2] Jonathan Edwards, Letters and Personal Writings (WJE Online Vol. 16) , ed. George S. Claghorn (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 794; see also Stoll, Inherit the Holy Mountain, 23.

[3] Brett Malcolm Grainger, Church in the Wild: Evangelicals in Antebellum America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019), 31–32; John Ffirth, Experience and Gospel Labors of the Rev. Benjamin Abbott (New York: T. Mason and G. Lane, 1836), 13.

[4] Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1844–1845, p. [10] [miscellany], https://

[5] Roderick Frazier Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind, 4th ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 24, 30–32.

[6] See Grainger, Church in the Wild, 29–30.

[7] See Stoll, Inherit the Holy Mountain, 115.

[8] Joseph Smith, History, circa Summer 1832, in The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, 2:283 (hereafter JSP, D2); see Joseph Smith—History 1:14; Grainger, Church in the Wild, 62.

[9] Joseph Smith, Journal, 9–11 November 1835, in The Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, 1:88.

[10] Orson Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste (A Cry out of the Wilderness, 1842, extract, English translation), https://

[11] See Revelation, 6 May 1833, in JSP, Documents, 3:89 [D&C 93:29, 36].

[12] Letter to Emma Smith, 6 June 1832, in JSP, D2:249–51.

[13] See, for example, 3 Nephi 21:22–24; Ether 13:6; Revelation, ca. 7 March 1831, in JSP, Documents, 1:280 [D&C 45:64–66] (hereafter JSP, D1).

[14] Revelation, 6 June 1831, in JSP, D1:328 [D&C 52:3–5].

[15] Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, volume A-1, 23 December 1805–30 August 1834, p. 126, josephsmithpapers.org.

[16] Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, volume A-1, p. 127, josephsmithpapers.org; see also 3 Nephi 21:22–24; Ether 13:6.

[17] See Isaiah 35:1; Matthew C. Godfrey, “The Natural World and the Establishment of Zion, 1831–1833,” in Jedediah S. Rogers and Matthew C. Godfrey, Earth Will Appear as the Garden of Eden (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019), 74–75.

[18] Revelation, 7 May 1831, in JSP, D1:303 [D&C 49:24].

[19] “To the Elders of the Church of Latter Day Saints,” Messenger and Advocate 1 (September 1835): 179.

[20] See Revelation, 20 July 1831, in JSP, D2:7–8 [D&C 57:1–3].

[21] Revelation, ca. 7 March 1831, in JSP, D1:280 [D&C 45:64–66].

[22] See Godfrey, “Natural World and the Establishment of Zion,” 82–83.

[23] See Revelation, 7 August 1831, in JSP, D2:32–35.

[24] See William E. Foley, The Genesis of Missouri: From Wilderness Outpost to Statehood (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1989), 7–13; The History of Jackson County, Missouri, Containing a History of the County, Its Cities, Towns, Etc. (Kansas City, MO: Union Historical Company, 1881), 101–2.

[25] Ezra Booth, “Mormonism—No VI,” Ohio Star [Ravenna, Ohio], 17 November 1831, [3].

[26] Washington Irving, Independence, Missouri, to “Mrs. Paris,” New York, 26 September 1832, in Pierre M. Irving, The Life and Letters of Washington Irving (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1863), 3:33, 38.

[27] Edward Partridge, Independence, Missouri, to Lydia Clisbee Partridge, 5–7 August 1831, MS 23154, CHL.

[28] See Ezra Booth, “Mormonism—No. V,” Ohio Star, 10 November 1831, [3].

[29] Revelation, 1 August 1831 in JSP, D2:14, 17 [D&C 58:3, 37].

[30] Revelation, 7 August 1831, in JSP, D2:33 [D&C 59:15–17].

[31] See Revelation, 8 August 1831, in JSP, D2:36–37 [D&C 60].

[32] See Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, volume A-1, p. 142,, josephsmithpapers.org; Ezra Booth, “Mormonism—No. VII,” Ohio Star, 24 November 1831, [1].

[33] Hiram Martin Chittenden, History of Early Steamboat Navigation on the Missouri River (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1903), 1:80–81.

[34] Joseph Smith ,History, 1838–1856, volume A-1) p. 142.

[35] Revelation, 12 August 1831, in JSP, D2:39–44 [D&C 61:4–5, 14–19, 23–24].

[36] Elizabeth Godkin Marsh, Kirtland Mills, Ohio, to Lewis Abbott and Ann Abbott, East Sudbury, Massachusetts, September [1831], MS 23457, CHL.

[37] “The Way of Journeying for the Saints of the Church of Christ,” Evening and the Morning Star, December 1832, 53.

[38] Letter to Emma Smith, 4 June 1834, in JSP, Documents, 4:57.

[39] “Extracts from H. C. Kimball’s Journal,” Times and Seasons, 1 February 1845, 788. There are several accounts of Joseph Smith’s revelation on Zelph, some of which contain more detail than others. For an explanation of the different accounts, see Kenneth W. Godfrey, “The Zelph Story,” BYU Studies 29, no. 2 (1989): 31–56.

[40] “Remarks of Brother Nathan Tanner, in Regard to Zion’s Camp, Made at a Meeting of the Daughters of the Pioneers, Held on Saturday, October 24, 1903,” MS 9824, CHL.

[41] George A. Smith, reminiscences, p. 16, MS 1322, box 1, folder 2, CHL.