The First Vision within the Context of Revivalism

Rachel Cope

Rachel Cope, “The First Vision within the Context of Revivalism,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 65‒88.

Rachel Cope is an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

While Joseph Smith’s First Vision rings familiar to most Church members, the historical setting in which that theophany occurred remains a foreign world to many. While some have heard terms like burned-over district or Second Great Awakening, their sense of what those terms mean is often limited in scope. In fact, when narrating the First Vision, it is not uncommon for people to describe Joseph’s experience as if it occurred within a vacuum, void of ongoing reflection and continual spiritual seeking and separated from cultural and social influences. Such readings and interpretations, I argue, actually limit the meaning and significance of this sacred experience. Indeed, contextual knowledge of Joseph Smith’s religious environment—replete with individuals motivated by genuine religious curiosity, the quest for salvation, a desire to obtain a forgiveness of sins, and communion with the divine—enriches our understanding of the First Vision.[1] It also encourages us to value the experiences of seekers outside of our tradition and to recognize that God loves and responds to the prayers of all of his children. Furthermore, it enhances our sense of the many ways in which early American evangelical Christians encountered the divine—a recognition that neither compromises nor diminishes the import and uniqueness of Joseph’s First Vision.

Background

The religious environment in which Joseph Smith resided emerged long before his birth. In the mid-eighteenth century, a number of revivals occurred on both sides of the Atlantic—this Great Awakening, as it would later be known, gave birth to the evangelical movement.[2] Spiritual seekers of the time attended religious revivals anticipating that the Holy Spirit’s influence could be felt within such contexts; each hoped, and perhaps even expected, to have a personal experience of salvation.[3] As vast crowds of people encountered God individually, as well as collectively, and as the word of God became increasingly accessible to the uneducated as well as to those trained in the ministry, a growing sense of spiritual equality emerged.[4] In the context of these early revivals, ordinary women and men initiated the democratic style that would eventually characterize the early American republic.[5]

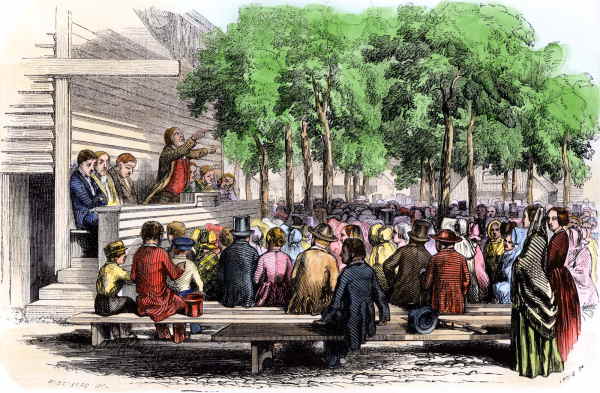

Women and men, wealthy and poor, elite and unknown, educated and uneducated attended revivals, prayed for revivals, and wrote about revivals. Hand-colored woodcut of a camp-meeting revival. Created by North Wind Picture Archives, 1850.

Women and men, wealthy and poor, elite and unknown, educated and uneducated attended revivals, prayed for revivals, and wrote about revivals. Hand-colored woodcut of a camp-meeting revival. Created by North Wind Picture Archives, 1850.

Following the American Revolution, a second period of religious revivalism emerged, stretching from the early 1790s into the mid-nineteenth century.[6] Itinerant preachers from various denominations traveled from place to place, sharing salvific messages that were laced with optimism. The Arminian view of free will—the potential that all could receive salvation—became more prevalent than the Calvinist view of a limited atonement reserved for the predestined.[7] Although upstate New York was one of the hotbeds of revivalism during the time, many burned-over districts emerged throughout the country: north, south, east, and west participated in the kinds of camp meetings that Joseph Smith described.[8] Countless individuals were drawn to the enthusiastic preaching that characterized such meetings, and many audience members participated actively, some even experiencing conversion and professing faith publicly.[9] Still others retired to private spaces, where they encountered divine forgiveness in deeply personal ways. The desire to share such experiences inspired many to profess their faith, some in public contexts, some in print, and others through correspondence or private conversations.[10] Regardless of the context, the zeal to evangelize struck most believers, and the belief that God could speak to and through anyone who sought divine guidance marked a growing commitment to democratized faith.[11] The evangelical movement that had taken root in colonial America began to flourish within the new nation.[12]

Genuine Religious Curiosity

The preponderance of revival meetings, which piqued the curiosity of teenage Joseph Smith, also fostered genuine religious curiosity within the hearts and minds of countless individuals, female and male, in nineteenth-century America.[13] To the pious Christian, the word revival implied “a renewal of the Spirit’s influence and operations, and a resuscitation of holy and devout feelings and exercises in the hearts of [believers].”[14] As one preacher noted, revivalism pointed to “times of spiritual awakening in which the church is quickened, wanderers reclaimed, and sinners saved.”[15] Revivals constituted a “refreshing” time sent from the Lord, a time when the Holy Spirit touched willing hearts and minds.[16] Underscoring this idea, another preacher explained, “When God’s servants were awakened to the use of special means for promoting [a revival], they often found that the Spirit had already ‘gone out before them.’”[17] Many of Joseph Smith’s contemporaries, believers and seekers alike, responded to God’s call to revitalize or initiate their faith, to experience conversion, and to attain a forgiveness of sins.[18]

Because revivals were so widespread, and because they implicitly and explicitly affected so many lives, a number of extant sources, public and private, recount noteworthy details about these events. Women and men, wealthy and poor, elite and unknown, educated and uneducated attended revivals, prayed for revivals, and wrote about revivals. Countless seekers announced the times and places in which revivals were held; encouraged friends, family members, community members, and congregations to pray for additional revival meetings to be organized; described the spiritual power that distilled upon revival participants; recounted conversion experiences; and reflected on the growth in grace that occurred in such settings. Such sentiments are captured by Cornelia Smith of Trumansburg, New York, who questioned: “O when shall we awake to our duties and pray more earnestly for a revival?” Although her hope for a local meeting was not realized immediately, this hope would eventually come to fruition. A few years after Cornelia expressed this desire, her minister informed her local congregation that everything in Trumansburg appeared to be ready for a revival.[19] Cornelia viewed this announcement as God’s answer to her heartfelt plea.

Although Cornelia had to wait patiently for a local revival to occur, many other individuals described geographic regions that seemed to be saturated with such meetings. Joseph Smith, for example, detailed the “unusual excitement on the subject of religion” that existed in his “region of [the] country” (Joseph Smith—History 1:5).[20] Similarly, Maria Porter of Huntington, New York, wrote a letter to her friend, Nancy Allen, describing how a growing interest in religion affected Maria’s community: “It is our firm belief that this place the beloved place of your nativity is about to be visited with a powerful revival of religion. Christians here, those who are awake, do not intend to be satisfied with small things but are pleading with earnestness for great blessings. About six weeks since our beloved pastor (who is wide awake himself) and the church thought but to set a part a day of fasting & prayer for a revival.”[21] Methodist convert Catherine Livingston Garrettson of Rhinebeck, New York, likewise made note of the “very gracious work” of revivalism taking place “all around us,” while Zina Baker Huntington of Watertown, New York, declared “there is [sic] revivals of religion all around us some places a few drops and other places a plentiful shower.”[22]

By using the imagery of rain to describe the effects of revivalism, Zina adeptly captures the scene of religious flourishing being manifest in evangelical circles throughout the early nineteenth century. Similar phraseology is repeated in a variety of sources written by her contemporaries, making it clear that upstate New York—and beyond—had become particularly prone to the “drops” and “showers” of “grace” and “mercy” that nourished spiritual seekers who had become “occupied” with the subject of religion.[23] A member of the Shaker Ministry in New Lebanon, New York, for example, declared, “Since the latter rains, and those refreshing showers from heaven descended, the drooping spirits have revived, and the withered plants spring up, and as it were the dry forest begins to bud and blossom, and to leap for joy.”[24] Using similar language, Catherine Livingston Garrettson recorded the following in her diary: “They were gracious showers, every little plant in Zion was watered—praise my God.”[25] Just as the rain that nourished crops enabled individuals to be sustained physically, the divine grace “descending in showers upon the assembly” slowly awakened those in need of spiritual rebirth.[26] These metaphoric showers nourished spirits and cleansed souls.

As accounts written by Joseph Smith’s peers demonstrate, he was not alone in his sincere quest as a religious seeker. He was surrounded by women and men who were equally affected by the revivals they encountered. Exposure to such meetings ignited within countless people a sense of curiosity about spiritual possibilities and even “reanimated” the “frequency of and credibility given to dreams and visions” that provided revelatory guidance.[27] The drops of grace and mercy that rained upon a once parched spiritual landscape provided sincere seekers with a multitude of choices about salvation. All had the opportunity to find a pathway to God. And many—including a teenage boy in Palmyra, New York—took that journey very seriously. The evangelical environment fostered by revivalism infused itself into Joseph Smith’s mind and heart and thus played an essential role in his quest for salvation.[28]

Quest for Salvation

Revival meetings—which served as a religious marketplace of sorts—offered an abundance of salvific choices to the spiritual seeker.[29] The movement of itinerant preachers from place to place, the emergence of camp meetings in a variety of localities, and a deep and abiding commitment to evangelization all had a democratizing influence that opened up space for the unlearned as well as the learned to preach and pray publicly, and that exposed people to more religious options than they had previously encountered.[30] Noting the role that religious diversity played in nineteenth-century New York, Alan Taylor contended that “the movement to the New York frontier exposed people to a proliferation of religious itinerants expressing an extraordinary diversity of belief.”[31] This included a plethora of Protestant denominations and “a great variety of distinctive local groups and defiant individuals in earnest search of their own truth.”[32] While this exposure fortified or enriched the faith of some seekers, others found that religious diversity led to internal confusion about which denomination to become affiliated with and how to attain salvation. In such cases, revival attendance led to more questions than answers. As one minister noted, people constantly contended over what they should “do to inherit eternal life.”[33] Reporting on an 1842 revival in Hammond, New York, for example, one person described a gnawing sense of internal turmoil:

My mind [is] so torn with conflicting opinions . . . but when I look around and view the many sects and denominations abroad on the earth all contending for the preeminence and all (differing as they do) prophesying to derive their doctrine from the bible I must say that I would give a world were possessed of one to know with a true and perfect knowledge which of them is right for there can be but one right way.[34]

Similar to this diarist, Lucy Mack Smith felt perplexed by the abundance of religious denominations and doctrinal differences that she encountered. For years, she searched from “place to place,” hoping to discover a church whose teachings resonated with her.[35] A similar search for the “one right way” characterized the lives of many religious seekers and enabled a sense of spiritual autonomy to develop within evangelical contexts. Indeed, the availability of choice made it possible for all to become active participants in a most important quest. Revival attendance thus served as a preparatory period that led to ongoing spiritual discovery and conversion.

Like his mother, Lucy, Joseph Smith felt perplexed by the abundance of religious choices that surrounded him. He noted that a “scene of great confusion” caused him to question “who was right and who was wrong.”[36] Though drawn to Methodism, he continued to wonder about other options.[37] This uncertainty encouraged him to engage in personal spiritual searching, pondering, and reflection in public and private settings.[38] Other seekers encountered similar feelings and experiences in their search for spiritual direction. Hoping to discover answers to her questions about salvation, Lucy F. Brown, a young woman living in Collins, New York, recalled attending Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Quaker meetings.[39] Similarly, Cornelia Smith attended Methodist, Presbyterian, and Quaker meetings and even noted the Millerite belief in the immediacy of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. She wrote, “It has been predicted by some that time will end this year or the beginning of the next be this as it may, time may soon end with me therefore I ought to live prepared.”[40] Attendance at a variety of denominational meetings denoted the search for specific answers. The earnest of heart explored every option. Revivals allowed individuals to make their own—even radical—choices, often based on personal spiritual impressions rather than being solely influenced by the words of a preacher.

In addition to reflecting upon the spoken word, many who attended revival meetings felt compelled to further cultivate their spiritual pilgrimages by reading the Bible and other devotional literature—a pursuit that often inspired deep pondering and reflection.[41] People engaged their hearts and minds as they made their spiritual quests. Budding believers hoped to find answers to their prayers within the pages of sacred text. Personally concerned with questions about salvation, Cornelia Smith declared, “I ought to be thankful that I have my Bible to be read, & my Prayer is that the Lord would enable me to understand it a right.”[42] Similarly, Catherine Livingston Garrettson spent considerable time reading the Bible. She eventually became acquainted with additional religious texts that would redirect the course of her life. Catherine explained, “These books had opened to me the way to get religion and the only way to keep it when attained.”[43] Later, recognizing the intense value of doctrinal study for those immersed in a spiritually awakened state, Catherine declared, “I would recommend a diligent reading and meditating of the word of God [there is] nothing better to form our belief upon.”[44] On another occasion, she exclaimed, “I invite you to read the word of God, to read it with prayer and supplicate the Lord Jesus Christ to reflect light upon your mind and so change your heart that you may begin to live, and be daily preparing for a mansion in the skies.”[45] Such intellectual engagement—pondering, searching, and reflecting upon sacred texts—inspired sinners to seek God personally. Private as well as public prayers that followed such study would often result in answers that responded to questions about salvation.

Forgiveness of Sins/

Revival meetings instilled within many hearts and minds the desire for conversion.[46] In the context of these religious settings, repentant sinners hoped to be awakened to their need for the divine, encounter God’s mercy, attain his forgiveness, experience spiritual rebirth, and gain hope for salvation. For the spiritual pilgrim, conversion referred to deep personal change through the redemptive power of Christ—or as historian Bruce Hindmarsh defines it, the “recovery of the right relationship with God.”[47] Attempting to distinguish between an awakened interest in religion as experienced at revival meetings and spiritual birth as experienced through the redemptive power of Christ, Livingston Garrettson explained, “Do not . . . be looking [only] for conviction, but seek earnestly for conversion: this will make you happy in your choice, and under the means of grace you will thrive and ripen for eternity.”[48] Conviction confirmed beliefs, while spiritual birth centered on a changed heart and an “entire change of mind.”[49] As one minister noted, “I believe a considerable number have experienced a change of heart. But I do not think all experienced such a change, who entertained such a hope of themselves, and concerning whom others entertained a hope.”[50] Noting the transformative power of conversion, an article in one Christian periodical declared, “Instead of seeking salvation with penitent, believing hearts, in holy obedience to the will of God, they now prayed for new hearts, hoping that God would hear their prayers, and deliver their souls from death.”[51]

Although many longed for immediate conversion—including Joseph Smith, who questioned why his experiences at revival meetings did not mirror those he perceived others to be having—most seekers actually waited for an extended period of time before experiencing the spiritual pardon they hoped to encounter.[52] The failure to attain spiritual birth as quickly as anticipated is described in countless conversion narratives and spiritual diaries—thereby suggesting that Joseph’s experience of feeling perplexed and uncertain while immersed in a continuing process of spiritual searching was more typical than atypical. Emilie Royce Bradley of Clinton, New York, for example, longed to be justified with “an act of free grace by which God pardons the sinner and accepts [her] as righteous, on account of the atonement of Christ.”[53] But the changes she hoped to experience did not come in the ways, nor within the time frame, she expected. Emilie eventually recognized the necessity of patience as she engaged in an ongoing redemptive process enabled by the grace of her Savior. In a similar vein, Livingston Garrettson explained her early spiritual failures as follows: “I see that in too many things, I have desired the will of God to be done in my own way. I now find it the desire of my soul to have no will of my own; but to sink into his in all things.”[54] Spiritual seekers slowly learned to align their wills with God’s will and to rely upon and accept the righteousness of Christ as their only hope for salvation. This “mighty change” prepared them to “begin to live for eternity” as they embarked upon the continuing quest for a sanctified life.[55]

Revival meetings—and the reflecting, pondering, study, and prayer that they encouraged—helped many faithful seekers recognize that conversion required more than a belief in the divine. Perhaps no theme is more central in the religious journals, diaries, correspondence, narratives, and memoirs of nineteenth-century New York women and men than their eventual discovery of their absolute need for Christ. As hearts softened, as minds changed, they could, like Catherine Livingston Garrettson, declare: “The great question is not are we willing? No; tis are we ready? Have we found the refuge? Have we become new creatures in Jesus Christ?”[56] Spiritual birth constituted Christ-centered change, and that change led to the pathway of salvation.

When the heart is regenerated, contemplation on the divine character is habitual, vigorous, and operative; attended with ardent affection. . . . To the renewed mind God is the choice of the heart, the centre of the affections. The soul that is born again considers the glory of God, manifested in the felicity of the universe, as the supreme and ultimate object of desire; and makes everything else subordinate to this. . . . Those . . . who are born of God, are sensible that it is the duty of every rational creature to love God with all the heart, and to consecrate all their powers and faculties to the Creator. . . . Those who [have] been renewed in the disposition of their mind, find it their pleasure and their delight to discharge the duties of religion, to engage in the worship of God, and to be constantly employed in those actions, which he has prescribed.[57]

Hopeful converts discovered that conforming to Christ, attaining a forgiveness of sins, and discovering the pathway to salvation required deep spiritual transformation.

Describing her journey to justification, Caroline Ludlow Frey remembered an early awareness of her “lost condition” that led to conviction but not change. She attended revivals, intending to be “earnest about my eternal welfare,” but her worldly desires continued to consume her. Still deeply concerned about the prospect of her salvation, Caroline resolved to seek forgiveness earnestly. Following an intense period of internal searching, conversion finally resulted. She recalled, “Jesus—shout great glory to his name who after all my provocations—did visit me as I humbly trust and did redeem me from the curse.”[58] As a result of this experience, Caroline resolved to live a life of holiness devoted to God’s prescribed course. Speaking in prayer, she ultimately declared, “I consecrate myself to thy service to do thy will in all things” through the “borrow[ed] strength of Christ.” She then concluded, “Purify me and fit me to dwell with thee forever.”[59] Conversion came when Caroline recognized that Christ was her all, and thus her salvation. Joseph Smith would have an experience similar to Caroline’s; it was only when he called upon his Savior for “deliverance” from darkness that he saw divine light and received a forgiveness of his sins.[60] The conversion experience he sought came as he communed with the divine.

Communion with the Divine

Although a number of individuals recounted experiences of spiritual birth that occurred within the context of revival meetings, the vast majority of converts encountered divine forgiveness in quiet, peaceful moments that occurred within private spaces in nature or at home. As historian Brett Grainger explains, “Retreating to the woods under a state of conviction became a standard trope in conversion narratives during the Second Great Awakening.”[61] This was certainly the case for Charles Finney—a Presbyterian minister and famed revival preacher in upstate New York during the Second Great Awakening—and Joseph Smith, both of whom experienced conversion in sacred groves.

Approximately eighteen months after Joseph’s First Vision, Charles entered a grove of trees in Adams, New York, on a beautiful morning in October 1821, determined to either surrender his heart to God or die in the process. In this spiritually vulnerable state, Charles had a visionary experience in which he encountered the divine—in many ways similar to the experience later recounted by Joseph Smith.[62] Both young men were influenced by scriptural passages that encouraged and enabled dialogue with God, both encountered bright light followed by a visible witness of their Savior, and both received the promise of justification, as well as hints of personal callings that would affect not only their futures, but also the lives of countless seekers of conversion throughout New York State and beyond. The remarkable parallels between Joseph’s and Charles’s accounts, or between any number of visionary narratives written by their contemporaries, do not diminish the import of the Restoration but rather reflect God’s love for all of his children—a reminder that the divine is not a respecter of persons (see Acts 10:34–35). God hears and answers all who pray. Indeed, much like Joseph and Charles, other individuals, including Levi Parsons, Catherine Livingston Garrettson, Benjamin Abbott, Lucy Mack Smith, and Enoch Edwards recalled retiring to the woods to pray prior to or after revival meetings or when searching for answers to their own questions.[63] In these verdant surroundings, they, too, discovered that the distance between humans and the divine seemed to dissipate. It was within the context of their own “sacred groves” that God’s infinite love became abundantly apparent to those seeking him.

In addition to praying in natural settings, many spiritual seekers prayed within quiet spaces at home, often in the middle of the night, when they could be entirely alone with God. Catherine Livingston Garrettson, who regularly prayed within her private chamber, believed that her intercessions “were heard and would be answered.” She anticipated and described “sweet fellowship with the father & his son Jesus Christ.”[64] Underscoring this point, she recorded a powerful experience she had one morning:

I felt then I have all day wiling to commit my way unto the Lord. I trust that he will direct me. I love to reflect upon all his dealings with me; to trace his fingers in the slightest circumstances of my life; view the important bearing such circumstances have had upon my life, & ascribe it all to God. I rejoice that I am entirely in his hands, I would be no where else. O that not only the events of my life may be over ruled by the Almighty, but my heart be so cleansed from retribution of sin, & filled with the blessed spirit, that even my thoughts be not my own, but thine entirely, my very dreams devout.[65]

Catherine’s spiritual expectations were rooted in a past laced with multiple visionary experiences. God often conveyed his purposes to her through dreams and powerful spiritual manifestations. She even had a transformative experience in which she encountered the three beings of the Trinity in deeply powerful, tangible, and personal ways.[66] As a result, she became committed to the ongoing process of sanctification—ever determined to become and remain God’s faithful servant.

Adaline Lindsley also encountered God within a private setting. As a young student in the female department of the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima, New York, she became increasingly concerned about her eternal welfare.[67] Consequently, Adaline attended a revival meeting that further ignited her desire for conversion. Afterwards, she knelt in private communion with God; she rejoiced as she felt his love and gained confidence in the redemptive power of her Savior. Ultimately, Adaline experienced the “infusion of a new life,” as “the seed, which had already germinated in her heart, suddenly burst into blooming vegetation.”[68] God’s mercy changed her heart and renewed her mind, thus making space for ongoing spiritual development.

Lucy Brown likewise attended a plethora of revival meetings. Although too embarrassed to join with those engaged in public expressions of commitment, she experienced feelings of conviction in such settings. On one occasion, finally attaining the courage to join with the spiritually affected, Lucy went forward but “did not feel any relief in mind while there.” Upon returning home, just prior to midnight, her parents and she read from the Bible and prayed. After her parents retired to bed, Lucy continued to ponder. Exhausted, she finally made her way to her bedroom between the hours of 2:00 and 3:00 a.m. As she settled into her bed, she recalled feeling “willing to be anything or do anything if I could only feel God’s pardoning love shed abroad in my soul.” As those thoughts passed through her mind, she experienced internal change. “I immediately felt relieved both in mind and body,” she recalled. Upon awaking the next morning, Lucy noted that “I felt very calm every thing looked different. To me it seemed as though every thing was a praising God and I have felt ever since and now feel determined to persevere until I arrive in that better world.”[69] Alone with God in the silence of the night, Lucy finally understood her role as spiritual pilgrim. Like Catherine, she discovered that becoming “new creatures” through Christ was the “one [and] only way of admission into the presence of God.”[70] This new birth, which “implies a change of heart, to use differently, to feel differently . . . to love Him better who has created them anew,” was, she believed, an essential part of the salvific journey.[71]

In quiet, private moments, earnest seekers spoke to God. As they listened with spiritually attuned ears, they heard his voice promising forgiveness, peace, and hope. Often, these answers came slowly, but when they came, they came with power. “Light did not break in upon me suddenly,” Emilie Royce Bradley wrote, “but as I read the 36th chapter of Ezekiel I could see a grace and beauty in the way of salvation. The Lord there promised to give a clean heart to the children of Israel for his own namesake & I felt willing to receive one for that reason.”[72] While quietly communing with God, Emilie, like so many of her contemporary seekers, finally experienced conversion. Revivals had shaped her desire to develop a relationship with the divine. The quiet reflection and pondering she engaged in following those meetings eventually led her to the answers and the experiences she sought. Joseph Smith would tell a similar story. It took years of “serious reflection” and thoughtful contemplation before the voice of God spoke directly to his soul.[73] When that occurred, he too, finally felt a sense of spiritual peace and direction in his life.

Conclusion

Raised in a culture, and within a family, that encouraged religious seeking, Joseph Smith learned from an early age to be among the spiritually curious. Aware of and a participant in revival meetings, he undoubtedly witnessed countless conversion experiences. He also heard powerful professions of faith. He listened to thought-provoking sermons. He likely overheard personal conversations about spiritual experiences—conversations about justification and sanctification. He wanted to be forgiven as others had been. He wanted to experience salvation. So Joseph read the Bible. He pondered. He reflected. He wondered. He doubted. He hoped. The sincerity, as well as the insincerity of those around him, likely struck his heart and his mind. He, too, wanted to experience religion. He wanted to feel different. Young Joseph wanted to encounter God’s love, to feel his sanctifying power, to hear his voice. As he considered what to do, he likely responded to his awareness of the fact that people prayed—it was not uncommon to pray in a grove of trees in a quest for salvation. It was not uncommon to seek communion with the divine. It was not unusual to be a seeker of religious truth. Shaped and influenced by his culture, a sincere and spiritually rich culture that cultivated and nurtured his own curiosity and promptings, Joseph prayed vocally. He spoke to God. By crying out for mercy, he rejected darkness and embraced light. And in response, God spoke to him—just as he spoke with so many of Joseph’s contemporaries. This did not seem unusual to Joseph; he had heard about this type of experience. He knew people had visions. He knew individuals communed with the divine. But Joseph eventually recognized a deeper message laced throughout the personal forgiveness and justification that most people received—a message that hinted at more to come, a message that played upon his heart and mind for several years until he prayed earnestly again, a message that encouraged him to seek and receive more. Joseph would eventually receive second and third and fourth visions—visions that led to restoration. These visions had been influenced by and built upon the powerful religious culture—initiated by revivalism—that had encouraged, motivated, enriched, and shaped the person, indeed the prophet, that he would slowly become.

Notes

[1] See, for example, Catherine Brekus, Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013); D. Bruce Hindmarsh, The Evangelical Conversion Narrative: Spiritual Autobiographies in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Lincoln Mullen, The Chance of Salvation: A History of Religious Conversion in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017); Phyllis Mack, Visionary Women: Ecstatic Prophecy in Seventeenth-Century England (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992); Phyllis Mack, Heart Religion in the British Enlightenment: Gender and Emotion in Early Methodism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Mechal Sobel, Teach Me Dreams: The Search for Self in the Revolutionary Era (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Paul Chilcote, ed., Early Methodist Spirituality: Selected Women’s Writings (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2007); Richard Lyman Bushman, “The Visionary World of Joseph Smith,” BYU Studies 37, no. 1 (1997–98): 183–204.

[2] See David Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman, 1989); Thomas Kidd, The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007); Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); Catherine Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Rebecca Larson, Daughters of Light: Quaker Women Preaching and Prophesying in the Colonies and Abroad, 1700–1775 (New York: Knopf, 1999); Susan O’Brien, “A Transatlantic Community of Saints: The Great Awakening and the First Evangelical Network, 1735–1755,” American Historical Review 91 (1986): 811–32; Hindmarsh, Evangelical Conversion Narrative.

[3] See, for example, Hindmarsh, Evangelical Conversion Narrative.

[4] Although Puritans and others had long believed in spiritual equality, the democratization of American Christianity that Nathan Hatch describes opened up space for the poor and the untrained to speak in behalf of God and preach to vast crowds. See Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Vertuous Women Found: New England Ministerial Literature, 1668–1745,” American Quarterly 28, no. 1 (1976): 20–40; Jerald C. Brauer, “Conversion: From Puritanism to Revivalism,” Journal of Religion 58, no. 3 (1978): 227–43; Charles E. Hambrick-Stowe, The Practice of Piety: Puritan Devotional Disciplines in Seventeenth-Century New England (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 197; Catherine A. Brekus, “Writing as a Protestant Practice: Devotional Diaries in Early New England,” in Practicing Protestants: Histories of Christian Life in America, 1630–1965, ed. Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, Leigh E. Schmidt, and Mark Valeri (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 19–34; Nathan Hatch, Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989).

[5] See Hatch, Democratization of American Christianity, 5.

[6] See, for example, Dickson D. Bruce, And They All Sang Hallelujah: Plain-Folk Camp-Meeting Religion, 1800–1845 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1974); Firth Haring Fabend, Zion on the Hudson: Dutch New York and New Jersey in the Age of Revivals (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000); Nancy A. Hardesty, Your Daughters Shall Prophesy: Revivalism and Feminism in the Age of Finney (Brooklyn, NY: Carlson, 1991); Nancy A. Hewitt, Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1722–1872 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984); Charles A. Johnson, The Frontier Camp Meeting: Religion’s Harvest Time (Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press, 1985); Curtis D. Johnson, Islands of Holiness: Rural Religion in Upstate New York, 1790–1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989); Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-Over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800–1850 (New York: Harper and Row, 1950); Paul E. Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815–1837 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004); Charles R. Keller, The Second Great Awakening in Connecticut (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1968); Marianne Perciaccante, Calling Down Fire: Charles Grandison Finney and Revivalism in Jefferson County, New York, 1800–1840 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2003); Mary P. Ryan, Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790–1865 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Marvin S. Hill, “The Rise of Mormonism in the Burned-Over District: Another View,” New York History 61, no. 4 (October 1980): 411–30; Alan Taylor, “The Free Seekers: Religious Culture in Upstate New York, 1790–1835,” Journal of Mormon History 27, no. 1 (2001): 44–66; Michael Barkun, Crucible of the Millennium: The Burned-Over District of New York in the 1840s (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1986); John Wigger, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Susan Juster, Disorderly Women: Sexual Politics and Evangelicalism in Revolutionary New England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994); Linda K. Pritchard, “The Burned-Over District Reconsidered: A Portent of Evolving Religious Pluralism in the United States,” Social Science History 8, no. 3 (1984): 243–65; Brett M. Grainger, Church in the Wild: Evangelicals in Antebellum America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

[7] See E. Brooks Holifield, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 83; Mark Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

[8] See Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims, 294, 314.

[9] See Susan Juster, “‘In a Different Voice’: Male and Female Narratives of Religious Conversion in Post-Revolutionary America,” American Quarterly 41, no. 1 (March 1989): 34–62.

[10] Brekus, “Writing as a Protestant Practice,” 29.

[11] See Hatch, Democratization of American Christianity.

[12] See Kidd, Great Awakening.

[13] See Nancy Cott, “Young Women in the Second Great Awakening,” Feminist Studies 3, no. 1/

[14] “Divinity,” Methodist Protestant, 15 April 1831.

[15] L. D. Davis, History of the Methodist Church (Syracuse: Hamilton, 1855), 122–23.

[16] Presbyterian Magazine 1, January 1821, 21.

[17] Reverend R. Smith, Recollections of Nettleton and the Great Revival of 1820 (Albany, NY: E. H. Pease, 1848), 15–16.

[18] See Davis, History of the Methodist Church, 122–23.

[19] Cornelia Smith Diary, 30 October 1836 and 26 February 1839, Cornelia H. Smith Papers, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

[20] “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons (15 March 1842): 727.

[21] Maria Porter to Mrs. Nancy Allen, 30 March 1827, Porter Family Papers, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

[22] Catherine Livingston Garrettson Diary, 13 October 1829, Garrettson Family Papers, Special Collections, Methodist Library, Drew University, Madison, New Jersey (hereafter Methodist Library, Drew University). Zina Baker Huntington to Dorcas Baker, 8 June 1822, LDS Church Archives. For context, see Cott, “Young Women in the Second Great Awakening,” 15.

[23] For examples of this language, see Methodist Protestant, 14 October 1831, 326; Presbyterian Magazine, 3 March 1821, 142; Cornelius C. Cuyler, “Revival of Religion in the Reformed Dutch Church at Poughkeepsie under the Pastoral Care of Rev. Cornelius C. Cuyler,” Utica Christian Magazine 3, no. 1 (24 April 1815); “1st Revivals of Religion,” Utica Christian Repository 3, 3 March 1824, 91; Abner Chase, “Revivals of Religion on Ontario District,” Methodist Magazine VII, 1824, 435; Abner Chase, “Recollections of the Past” (Joseph Longking, Printer, 1846); Livingston Garrettson Diary, 7 June 1802, 17 June 1812, 10 June 1802, 1 January 1805, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[24] Letter of Grove Write to Ministry New Lebanon, 16 November 1837. Quoted in a letter from Ministry New Lebanon to Ministry South Union, 13 December 1837, Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio (microfilm copy, New York State Library, Albany, New York, IV A 12).

[25] Livingston Garrettson Diary, 1 January 1805, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[26] Livingston Garrettson Diary, 7 June 1802 and 17 June 1812, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[27] Kirschner, “‘Tending to Edify, Astonish, and Instruct,’” 201; see Henry Rack, “Early Methodist Visions of the Trinity,” Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society 46, no. 3 (1987): 57–69; Sobel, Teach Me Dreams, 17–54; Carla Gerona, Night Journeys: The Power of Dreams in Transatlantic Quaker Culture (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004), 205; Ann Taves, Fits, Trances, and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from Wesley to James (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

[28] Gordon Wood, “Evangelical America and Early Mormonism,” New York History 61, no. 4 (October 1980): 358–86; Taylor “Free Seekers,” 45.

[29] See Charles Sellers, Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815–1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 203–4; R. Laurence Moore, Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 42–43.

[30] See Steven Marini, Radical Sects of Revolutionary New England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 15; Hatch, Democratization of American Christianity, 125.

[31] See Taylor, “Free Seekers,” 45.

[32] Taylor, “Free Seekers,” 45; see Cross, Burned-Over District, 55.

[33] Nathaniel Dutton Diary, 6 March 1806, Nathaniel Dutton Diary and Accounts Manuscripts and Special Collections, New York State Library, Albany, New York.

[34] Letter written from a sibling about religious revivals in Hammond, New York, 14 May 1842, Alfred Bosworth Child Family Papers, Church History Library; Jonathan Pearson Diary, 18 July 1830, Union College Archives. Similarly, Jonathan Pearson of Schenectady, New York, declared: “I have so many minds about the subject [of religion] that I hardly know what to conclude about it. . . . It is lamentable that those who call themselves the worshipers of the same God should be so disunited and so as not to go to each other’s meeting[s] in some cases. These things seem to be inconsistent with the character of the followers [of] Christ and I think it to be better if they would be more united.”

[35] Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1844–1845, Page [5], bk. 2, https://

[36] Joseph Smith, History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2], p. 2, https://

[37] See Christopher Jones, “The Power and Form of Godliness: Methodist Conversion Narratives and Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no. 2 (2011): 89; Stephen Fleming, “The Religious Heritage of the British Northwest and the Rise of Mormonism,” Church History 77, no. 1 (March 2008): 80–81; Stephen Fleming, “John Wesley: A Methodist Foundation for the Restoration,” Religious Educator 9, no. 3 (2008): 131–49.

[38] See Joseph Smith, History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2], p. 2, https://

[39] See Lucy F. Brown to Cordelia Brown, 12 May 1836 and 6 June 1837, Cordelia Brown Papers, Church History Library.

[40] Cornelia H. Smith Diary, 11 February 1838 and 31 July 1843, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

[41] See Candy Gunther Brown, The Word in the World: Evangelical Writing, Reading, and Publishing in America, 1789–1880 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004); David Paul Nord, Faith in Reading: Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004); Matthew Brown, The Pilgrim and the Bee: Reading Rituals and Book Culture in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007); Seth Perry, Bible Culture and Authority in the Early United States (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

[42] Cornelia H. Smith Diary, 4 October 1835, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

[43] Autobiography of Catherine Garrettson, Rhinebeck, 4 March 1817, Methodist Library, Drew University, 8.

[44] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Edward Livingston, 4 October 1821, box 2, folder 25, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[45] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Edward Livingston, 13 October 1821, box 2, folder 25, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[46] See Mullen, Chance of Salvation; Lewis Rambo, Understanding Religious Conversion (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993).

[47] Hindmarsh, Evangelical Conversion Narrative, 7.

[48] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Mary Suckley, 29 June 1830, box 2, folder 32, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[49] “Biography,” Massachusetts Missionary Magazine 3, June 1805, 14.

[50] Seth Williston, “Revival of Religion in Durham, Green County, New York,” Utica Christian Magazine 1, July 1813.

[51] “Religious Intelligence,” Massachusetts Missionary Magazine 1, October 1803, 234.

[52] See Joseph Smith, History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2], p. 2–3, https://

[53] Papers of Emilie Royce Bradley, Diary, 26 June 1831, Dan Beach Bradley Family Papers, Oberlin College Archives, Oberlin College Library, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio (hereafter Emilie Royce Bradley, Diary, Oberlin College Archives). The 1828 Webster’s Dictionary defined justified as follows: “In theology, to pardon and clear [from] guilt; to absolve or acquit from guilt and merited punishment, and to accept as righteous on account of the merits of the Savior, or by the application of Christ’s atonement to the offender.” Webster’s Dictionary 1828, s.v. “justify,” http://

[54] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Catherine Rusten, 30 March 1790, box 2, folder 31, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[55] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Edward Livingston, 18 March 1836, box 2, folder 25, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[56] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Edward Livingston, 6 September 1813, box 2, folder 25, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[57] “Letter to the Young,” Massachusetts Missionary Magazine 5, September 1807, 135.

[58] Caroline Ludlow [Frey] Diary, 21 March 1821, New York State Historical Society.

[59] Caroline Ludlow [Frey] Diary, 21 March 1821.

[60] Joseph Smith, History, circa Summer 1832, p. 1–3, https://

[61] Grainger, Church in the Wild, 31.

[62] See Memoirs of Reverend Charles G. Finney Written by Himself (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1876), 13–23.

[63] See Daniel O. Morton, comp., Memoir of the Rev. Levi Parsons, Late Missionary to Palestine (Poultney, VT: Smith and Shute, 1824; repr., New York, Arno, 1977), 18; Livingston Garrettson Diary, Methodist Library, Drew University; The Experience, and Gospel Labours, of the Rev. Benjamin Abbott (New York: Daniel Hitt and Thomas Ware, for the Methodist Connection in the United States, 1813), 16; Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, p. 75, https://

[64] Livingston Garrettson Diary, 11 June 1839; 29 November 1840; 15 April 1840; 29 November 1840; 28 March 1839, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[65] Livingston Garrettson Diary, 1 May 1832, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[66] See Livingston Garrettson Diary, 10 and 11 March 1792, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[67] The Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, founded by the Genesee Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, opened in 1832. In 1849 Genesee College was founded on the same campus. This institution was relocated to Syracuse, New York, in 1870 and became Syracuse University. See Joseph Cross, Portraitures and Pencilings of the Late Mrs. L. A. L. Cross by Her Husband (Nashville: Nashville and Louisville Christian Advocate, 1851), 24.

[68] Cross, Portraiture and Pencilings, 24–26.

[69] Lucy F. Brown to Cordelia Brown, 6 June 1837, Cordelia Brown Papers, Church History Library.

[70] Catherine Livingston Garrettson to Edward Livingston, 18 March 1836, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[71] Livingston Garrettson Diary, 22 February 1811, Methodist Library, Drew University.

[72] Emilie Royce Bradley, Diary, 26 June 1831, Oberlin College Archives.

[73] Joseph Smith, History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2], p. 2, https://