Excitement on the Subject of Religion

Controversy within Palmyra's 1819 and 1820 Preaching District

Mark L. Staker and Donald L. Enders

Mark L. Staker and Donald L. Enders, “Excitement on the Subject of Religion: Controversy within Palmyra's 1819 and 1820 Preaching District,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 109‒28.

Mark L. Staker is master curator of the Historic Sites Division in the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Donald L. Enders is master curator (retired) of the Historic Sites Division in the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Preachers in Palmyra, March 1820

On 11 March 1820, four Methodist preachers were in Palmyra, New York, for a gathering of church officials and worshippers.[1] Their routes or circuits took them from village to village and township to township in a string of scheduled stops through their assigned region, where they preached sermons in homes, barns, and fields at regular meetings throughout the week. Their circuits made up the eight-month-old Ontario District of the Genesee Conference, which included Palmyra. And the preachers gathered at Palmyra village in the northern section of the township to compare notes with other circuit riders in the district and to address large crowds at what appears to have been a two-day quarterly meeting. This meeting was probably planned and announced the previous fall, but it was timely in March. It fell in the middle of upheaval in their district and its associated turmoil because of a series of well-attended public debates that made for unusual excitement in a rural region that had little public entertainment. At least some of the notes they compared at the Palmyra gathering likely addressed the bitter debates, and one or more of the preachers undoubtedly made the controversy a subject of an aggressive, emotional sermon.

The presiding elder in the district was twenty-six-year-old George Gary. Elder Gary began preaching in Vermont when he was sixteen and was put in charge of the Ontario District when it was formed the previous July.[2] Methodism was young. Many of its preachers were young. And many of its members were younger still. Only one of the group’s four Methodist preachers, thirty-seven-year-old William Snow, had much experience on the circuit. The others were just starting out. William Barlow barely had a few years of experience. John B. Alverson was a deacon. So was Andrew Peck. Peck had joined the Methodists when he was twelve and became a member of the Genesee Conference at eighteen when Bishop Roberts came to Palmyra to lead a revival.[3] Both Alverson and Peck were ordained deacons at the annual general conference the previous summer, where they were given the authority to baptize, although neither would be elected elder until 1821. Nineteen-year-old Peck served as Snow’s assistant in Ontario, and, like the others, he was anxious to impress.

When the men neared Palmyra, their identity as circuit riders was clear to settlers from a half mile away. Their distinctive outfits advertised the pending meetings as they rode toward the village. Although George Lane, a preacher they all knew well, would propose a change in the circuit rider’s dress code a few months later, everyone still immediately recognized their “old-fashioned, round-breasted coat, flat white hat, and smooth hair,” along with a pair of saddlebags draped over the hindquarters of their horses, all of which would remain mythic symbols of the circuit rider long after those styles were abandoned in practice.[4] Even young boys out on the farms lining the turnpike could tell from a distance there was a pending religious gathering in the village. The arrival of the men undoubtedly became the subject of over-the-fence talk, helping to spread news of the anticipated event, which with its food carts, tents, crowds of people, and sometimes contraband drink resembled a county fair.[5]

After the preachers settled in, Andrew mailed a letter to his brother George Peck, a twenty-two-year-old elder in the district who already had several years of preaching experience behind him, and Andrew sent greetings from the four to confirm their safe arrival. News of good health was always welcome. Four months later one of their close associates drowned while trying to cross the Susquehanna River on his way to their annual general conference.[6] Although George was only a long day’s journey from the Palmyra gathering, he did not attend. He had been active on the Tioga Circuit, which was part of the district where he preached in the Susquehanna Valley beginning in his late teens.[7] But during the winter of 1819 and into the spring of 1820, George was stationed in Waterloo, a village just north of Fayette, New York, on a different circuit. In addition to preaching on a different circuit, George was also distracted. He had been drawn into heated public debates with Baptists and Presbyterians over the ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. The men debated whether these ordinances were essential and, indirectly, what role they played in forgiveness for sin—a question any sinner seeking redemption would want answered and an issue George’s brother, Andrew Peck, likely took with him to the Palmyra meeting in March 1820.

The Methodist General Conference, July 1819

Widespread religious excitement was already evident at the Methodist general conference held in the district eight months earlier. The conference started on Thursday, 1 July 1819. These big gatherings were typically held in July or early August during the “laying by time” between the first grain harvest and the late summer corn cutting or fall planting, when there was opportunity to focus on the harvest of souls.[8] Methodist preachers from across the United States and Canada gathered in the woods at Oaks Corners just east of Vienna Road, almost sixteen miles south of Palmyra. They organized themselves in districts that represented New England, the mid-Atlantic states, the deep South, the Ohio frontier, Upper Canada, eastern New York, and, of course, the Genesee District of western New York, where—because travel was easy and such big events rarely, if ever, occurred in the lifetime of any preacher—all those who could do so made attending this conference a priority.

In addition to Methodist preachers, the general conference attracted seekers and the already converted—particularly the young—by including a scheduled sermon in a nearby church at the same hour every day. Onlookers from neighboring counties added to the thousands of people at the July conference. They joined the typical crowds from nearby villages, including Palmyra, where Joseph Smith Jr.’s family lived outside the village on the township line just north of Manchester township. Not only did worshippers and the curious gather, but sceptics came to mock and deride. Even ministers from competing congregations slipped into the crowd to watch the excitement.[9]

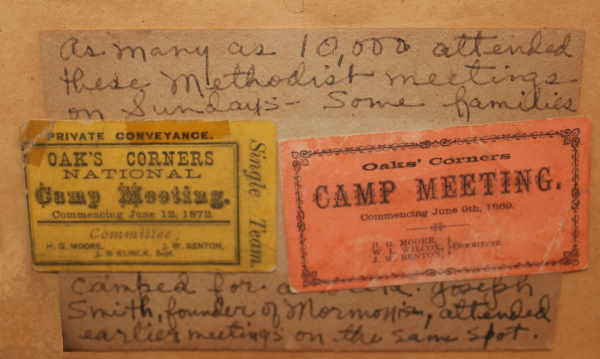

Oaks Corners was the perfect meeting ground for a large gathering. It had plenty of room and was easily accessed because of its location on the old Preemption Road that ran east of Manchester village. Travelers who took the Great Western Turnpike to Geneva could ride William Hildreth’s stagecoach on its Monday route, which stopped at Vienna (now Phelps), and walk to the preaching grounds. If they stayed on the stagecoach, it continued north through Palmyra and then on to Pittsford. On Thursday the stagecoach returned south through Palmyra, stopping at Vienna and then continuing to Geneva.[10] Travelers coming down from Palmyra through Manchester could leave Manchester village heading straight east to Oaks Corners. There Jonathan Oaks had a large yellow two-story inn, already showing the weathering of twenty-seven years of use, where he could entertain the senior ministers while others camped in tents in the woods. A small hamlet had grown around Oaks Inn, and the “Corners” included a modest church surrounded by log homes.[11] Behind the inn to the east, three brooks ran through different parts of a large grove of trees in a flat area that was ideal for watering enough people and their animals to populate a small city. Once the platforms were built and the other accoutrements of a camp meeting were in place, such as benches and sometimes makeshift privies, the woods off Vienna Road would be used again and again for Methodist meetings for a century.[12] The Oaks Corners preaching grounds at times accommodated more than ten thousand people gathered in soulful, energetic worship.[13]

These tickets to nineteenth-century camp meetings held at Oaks Corners are owned by the Jonathan Oaks family. Photograph courtesy of Mark L. Staker.

These tickets to nineteenth-century camp meetings held at Oaks Corners are owned by the Jonathan Oaks family. Photograph courtesy of Mark L. Staker.

The conference included organizational meetings and ran from Thursday to Thursday, ending on 8 July 1819, about the time the stagecoach passed by on its way south. On conference Sunday, which in 1819 was the Fourth of July—already one of the biggest holidays of the year—a series of prominent ministers assigned in advance preached to a large gathering of thousands, providing a string of the best sermons possible over the course of a day. Although the specific content of those long discourses has not survived, Andrew Peck later took the theme “gospel of liberty” with him to the March 1820 Palmyra gathering—it may have been an echo of the Fourth of July sermons.

Bishop Robert R. Roberts, who was ordained to his high office in 1818 and led a revival in Palmyra shortly afterward, took the chair of the July conference and presided over all the Methodist preachers in America.[14] Despite his high position, decades later Roberts still dressed in the old style and wore his hair in circuit rider fashion.[15] He would have looked like his fellow preachers standing before him.

All the men who later attended the March 1820 revival in Palmyra were also at the general conference. William Snow was the superintendent of the Genesee Conference and had responsibility for the work from upper Canada down into northern Pennsylvania. During the 1819 general conference, Snow relinquished his superintendent assignment to again be “received into the traveling connection,” and he returned to preaching on the circuit.[16] William Barlow was given responsibility for the Canandaigua Circuit and, together with another local minister, Abner Chase, was tasked to found a seminary within the bounds of the Genesee Conference in order to train the largely uneducated and young ministry. The two men were also elected at the meeting as delegates for the next general conference to be held in Lundy Lane, Canada, in 1820. Because Barlow presided over the Canandaigua Circuit, he knew the Palmyra Methodists well.

John B. Alverson and Andrew Peck were scarcely noticed at the meeting, but since they received their ordinations as deacons there, they would have been briefly on the preacher’s stand, where at least three of the general leaders would have laid hands on their heads. Although their initial call came from an inner prompting that God wanted them to serve, each man had to show himself capable of doing the work. He would eventually be elected by a congregation that needed to approve his ordination as an officiating elder in the church.

Each day of the July 1819 conference was filled with deliberation and discussion. The preachers separated into their six regional conferences for part of the time, but all met together to organize a Missionary and Bible Society and address other forms of business. Every afternoon, one of the preachers slipped away to give a sermon at a nearby church, but the public was primarily interested in the daylong preaching on Sunday, the Fourth of July. These sermons were usually delivered in a high falsetto that carried a long distance past large trees and over wind. They included a “glorious revival of the work of God among both preachers and people.” [17] The preachers assigned were well known and well liked. Their Fourth of July sermons were particularly calculated to reintroduce them to the public since they had been away from the circuit for a while. Men such as George Lane, Gideon Draper, and Thomas Wright spoke that Sunday, as did William Snow, one of the four who would visit Palmyra the next March.[18]

The Post-Conference Dimock-Peck Debates

A Baptist minister—the Reverend Davis Dimock—was evidently one of the people in the crowded woods who listened to the preachers, since on 28 August 1819 he told his own throng of attentive listeners about a recent visit to a large Methodist gathering where he saw irregularities in administering gospel ordinances. Dimock singled out baptism as something the Methodists considered “of no consequence.”[19] He went on to claim that many people who considered themselves Methodists had not been baptized, and he chastised them for neglecting an important ordinance. Dimock also criticized the Methodists for not requiring baptism before giving the sacrament since he observed that even the unbaptized received the ordinance at the gathering he attended.

Dimock was not the only minister listening in on the preaching of other denominations. George Peck, one of the Methodist ministers who had attended the July 1819 conference, was in Dimock’s crowd of listeners at the August gathering while the Baptist preacher attacked his Methodist faith. Peck mailed an angry response to Dimock two days later that accused him of “railing” on Methodists “in a heat of mind near to frenzy” and saying things about them that weren’t true, or—as Peck later acknowledged—were true in part but of no consequence.[20]

At twenty-two George Peck was older than some of his fellow ministers, although he still had limited theological training. But he and his associates relied on their book Doctrines and Discipline to learn the basics of their beliefs.[21] Peck referenced their standard volume when he accused Dimock of falsely representing Methodists: “You might have consulted our book of doctrine & discipline & saved yourself the trouble of making hasarding this assertion.”[22] Dimock responded to Peck by suggesting that “for some cause every statement you have made of what I said in my sermon is incorrect.”[23] Over the course of several letters back and forth, Peck adjusted his position on baptism slightly while learning to express his thoughts better. But he still approached the issue boldly. “I wish to know sir,” Peck asked Dimock, “by what scripture you make baptism the dividing line between the world & the church.” Peck didn’t seem to initially consider baptism as a requirement to join the body of Christ. But he did acknowledge that baptism and the sacrament were divine institutions, while he considered what he called “the weightier matters of the law—Judgment mercy & the love of God”—to be worthy of his focus rather than the ordinances.[24] Peck did not mention repentance or seeking forgiveness of sins in his letters, and the ideas are not discussed in the theological portion of the Methodist handbook Doctrines and Discipline except in scripture cited in notes.[25] But had he read the early Methodist theologians John Wesley, John Fletcher, or Adam Clarke, Peck would have seen that they argued baptism was part of the process of receiving “remission of sins [plural]” instead of only addressing the removal of original sin inherited by the Fall of Adam and Eve.[26] Although scripture was rarely cited in these arguments, the early writers—perhaps assuming readers already knew the proof texts well—made a point of noting that remission of sins was always in the plural in holy writ.[27] Peck continued in his letters to expound on his initial emphasis on judgment, mercy, and love as a notion centered on the belief that the truly penitent needed to acknowledge their sins and accept redemption from God. But as the discussion continued, Peck also seems to have come to recognize what most Methodists at that time were already arguing—namely, that baptism by water and baptism by the Holy Spirit were essential for achieving “means of grace” and were necessary to “become members of the Christian Church.”[28]

The letter debate spilled over into a public dispute as the two ministers continued to preach to large crowds. In December 1819, the Presbyterians became involved when Gideon Judd inserted himself into the middle of the debates. Judd was a thirty-two-year-old local Presbyterian minister who had recently graduated from the Princeton Theological Seminary. He and Peck argued face-to-face when Peck challenged Judd to a public debate—apparently one large enough to include the thousands of participants found at a typical camp meeting. But Judd declined “on account of the unhappy influence which it would probably exert on the cause of religion in general.”[29] Judd suggested, instead, a small debate in front of the members of their respective congregations. Peck did not note where the debate was held, how many attended, or who won (or believed they had won). He also did not mention Judd again. Judd would, however, later condemn the contention that developed between their respective denominations, since he hoped to see Christian goodwill dominate the preaching.[30] But despite Judd’s concern that the arguments between denominations would damage the cause of religion in general, contention spread.

Peck continued to attack Baptist Dimock. He wrote Dimock another letter in February 1820. Dimock quickly returned a lengthy response addressed to four ministers—suggesting a widening of the controversy. In his response, Dimock cited extensive scriptural and historical materials to show that baptism was the gate of entry into God’s kingdom, and John the Baptist was the porter who stood at the door and opened it.[31]

The debate continued well after the March 1820 Palmyra gathering; Peck responded to Dimock on 2 May 1820 and agreed with his Baptist counterpart on a few points, one being that “real Christians [and] real penitents are proper subjects of baptism.” Peck conceded that if someone wanted to repent of sin, baptism played a role in that process. But Peck continued to disagree on other points, including the age, mode, and consequences of baptism.[32] As the two men continued to preach in their scheduled string of villages, they continued to argue their interpretation of scripture to large audiences, and Peck adopted a position that included the need to search the scriptures and pray before baptism.[33]

Joseph Smith and Excitement on the Subject of Religion

Nothing in the surviving correspondence between George Peck and Davis Dimock or in Peck’s account of his conversation with Gideon Judd suggests the thirteen- or fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith Jr. heard any of their sermons during the last months of 1819 or early months of 1820. But knowledge of these debates helps put Joseph’s search for answers into a larger regional context.

Joseph later remembered that when he was “about” the age of twelve (the year 1818, when Bishop Robert R. Roberts led a revival in Palmyra following his ordination), his mind was seriously impressed with the concerns for the welfare of his soul, leading him to search the scriptures.[34] Around the time he turned fourteen in December 1819, Joseph recalled that there was an “unusual religious excitement” in the region.[35] While the rising interest in revivals on the district circuit was certainly the main excitement in the area, George Peck also believed his debates played an important role in the spread of religion. In an 1821 sermon, Peck recalled: “A short time previous to this I heard a sermon preached by Elder D. Dimmock on baptism in it he took occasion to oppose the principles of the Methodists . . . this gave rise to the exchange of several letters . . . which in the course of the year culminated in a number of conversions.”[36]

In addition to the Peck debates, camp meetings and religious revivals were drawing large crowds from the area. Palmyra farm laborer Durfey Chase lost half a day’s work in 1818 because he was “a going to the Methodist Camp Meeting.”[37] In early 1820, Palmyra laborer Nathan Eslow similarly lost work time by going to revival meetings. Later that same year, on 29 June 1820, Eslow asked his employer Lemuel Durfee for two dollars so he could attend another Palmyra revival.[38] While the “unusual religious excitement” Joseph Smith recalled may have been partly due to a revival meeting or due to a rising number of revivals in the region, large religious gatherings were common in the woods of western New York during the period of Joseph’s search. What made this period different was the additional “railing” attacks and the “frenzy” with which those attacks were pursued. The combination of meetings and debates on baptism raised interest on the Methodist circuits, including in Palmyra.[39]

If Davis Dimock was accurate in his characterization of Methodist preaching, the Peck-Dimock debates also underscore a rising emphasis on baptism by Methodists in the Genesee District. While they gave the ordinance little attention in 1819, by 1820 baptism as a means of saving penitents and receiving forgiveness for sins was increasingly part of the discourse. As one minister summarized those teachings, “Be baptized and wash away thy sins: Baptism administered to real penitents is both a means and seal of pardon. . . . Wesley never varied from this.”[40] As this emphasis grew, baptism became more important to seekers who were meeting in the woods of western New York and who wanted forgiveness for sins. The gatherings raised questions any seeker would want answered: Who had authority to baptize? Should baptism be by immersion? Did it bring forgiveness of sin, or was it a sign that forgiveness had already been conferred?

Lacking Wisdom

The doctrine of baptism was on the mind of the young Methodist ministers gathering in Palmyra in March 1820. As George Peck’s brother Andrew and his three associates rode up Vienna Road and entered Palmyra village, they narrowly avoided the deep ravine at the end of the road known as a “man trap” and then worked their way through the narrow passage left between stacks of boards and stinking vats alongside Edward Durfee’s mill and Deacon Henry Jessup’s tannery.[41] They came out onto Main Street in the business district of Palmyra village. Going east past John Swift’s small log blacksmith shop and his long narrow ashery then continuing for about a hundred yards, the four preachers came upon a large grove of trees that could accommodate many thousands. Here worshippers from the vicinity of Palmyra, Manchester, and the surrounding villages gathered to hear Methodist preaching.[42]

Although Andrew Peck did not mention in his 11 March 1820 letter to his brother George what he planned to say in the grove, the letter captures a sense of the excitement leading up to the gathering. It is torn, and part of it is missing. But the surviving material includes Andrew’s acknowledgment that George had given him good counsel and expressed a deep gratitude that “now and then” he was able to find a “Prodigal” who was willing to free him- or herself from the bondage of sin and join the gospel of liberty.[43]

Anyone aware of the excitement on the subject of religion then raging between the denominations in the district would want to be at the gathering in Palmyra to hear what the ministers had to say. When Joseph Smith later recalled his youthful search to decide which church he should “join,” he did not suggest what joining might entail or what role baptism might have played in joining. But as he went to the woods to pray in the early spring of 1820, seeking forgiveness for his sins, the contemporary debates on baptism could certainly have been among the issues he pondered when he went looking for answers.[44]

Notes

[1] See Andrew Peck to George Peck, 11 March 1820, George Peck Correspondence, 1820, box 1, George Peck Papers, Syracuse University Special Collections (hereafter Syracuse University), Syracuse, New York.

[2] See George Peck, Early Methodism within the Bounds of the Old Genesee Conference, from 1788 to 1828 (New York: Coulton and Porter, 1860), 486.

[3] See “Death of Rev. Andrew Peck,” 1887. The obituary was cut from the original newspaper—likely the Cortland Standard or The Cortland News—and is housed in the Cortland Historical Society collections. Thanks to Sophie Clough of the Cortland Historical Society for retrieving this information.

[4] George Lane proposed a change in clothing and hair requirements at the next general conference held in July 1820 at Lundy Lane, Canada. But the changes “on the subject of the dress of the preachers, etc. . . . in practice, like many conference resolutions, amounted to little,” as most of them continued to dress in a conservative style for years to come. See Francis W. Conable, History of the Genesee Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: Phillips & Hunt, 1885), 169.

[5] Two articles in the Palmyra Register on 23 June and 5 July 1820 suggest a James Couser had been drinking at a camp meeting held “in this vicinity,” which may have been at the Palmyra campground. For a detailed look at the potential significance of this discussion suggesting a June revival in Palmyra, see D. Michael Quinn, “Joseph Smith’s Experience of a Methodist ‘Camp-Meeting’ in 1820,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought: Dialogue Paperless, E-Paper #3 (12 July 2006). Another boy a little younger than Joseph Smith attended camp meetings in western New York in the 1820s and recalled that one of those meetings was broken up “by a drunken row.” A smuggler had gotten whiskey into the camp meeting and sold it at the food carts; when a Methodist preacher in disguise bought some of the smuggler’s wares and tried to have the culprit punished, a widespread quarrel ensued. The meeting fell apart in rancor, and the subsequent divisiveness contributed to the community not holding meetings in that vicinity for years. See M. M. Moss, ed., “Autobiography of a Pioneer Preacher [Jesse Jasper Moss],” Christian Standard 78, no. 3 (1 January–21 May 1938).

[6] See H. D. Paine, Paine Family Records 2, no. 8 (October 1882): 180. Emily Blackman suggested Paine had stopped at the river to bathe before continuing on to the conference. See Emily C. Blackman, History of Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, from a Period Preceding its Settlement to Recent Times (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen, and Haffelfinger, 1873), 139.

[7] See Mark L. Staker, “Isaac and Elizabeth Hale in Their Endless Mountain Home,” Mormon Historical Studies 15, no. 2 (2014): 1–105.

[8] Elizabeth Jo Lampl, “Historic Context Report: ‘A Harvest in the Open for Saving Souls,’ The Camp Meetings of Montgomery County,” Montgomery County Planning Department of Historic Preservation Section, Maryland Historic Trust, July 2004, 1.

[9] Zenana Gilbert, with friends and family, attended a Methodist “field Meeting” that had drawn about three thousand people who had all come “for the purpose of worshiping God some for pretents [pretense] and some to make show and some to see what they could find to make a ridicule of.” See Zenana Gilbert, Journal, September 1, [1817], Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

[10] See Elizabeth DeLavan, Upstate Village (Lakemont, NY: North Country Books, 1975), 15.

[11] The authors have studied the construction of the small church still standing in Oaks Corners. It appears to have been built in the late 1830s or early 1840s, and the original church was likely made of logs.

[12] George Peck does not include privies on his sketch of a camp meeting layout (see his sketch in the George Peck Papers), though they likely existed at the largest gatherings. The physical remains of the earliest campgrounds have not survived to confirm this. But campgrounds of the mid-nineteenth century included privies. They were placed outside the camp meeting area, thus requiring attendees to leave the meeting to access them. See Lampl, “Historic Context Report,” 81. Their placement outside the camp may have been prompted by Deuteronomy 23:12–13: “Designate a place outside the camp where you can go to relieve yourself. As part of your encampment, have something to dig with, and when you relieve yourself, dig a hole and cover your excrement” (New International Version). But the record is silent on their placement and use at these meetings.

[13] See Francis W. Conable, History of the Genesee Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: Phillips and Hunt, 1885), 158–60. Although all the official Methodist literature notes the conference was held in the village of Vienna (which was later renamed Phelps), the campground was located in the small community of Oaks Corners, just south of Vienna. This community had the necessary resources for the meeting. The daily preaching in a church, however, appears to have occurred in Vienna. A large grove of trees grew east of Oaks Corners and was watered by three separate streams. Later conferences held at this location issued tickets that allowed camp meeting participants to attend. Photographs of these tickets and information on half a century’s worth of camp meetings at Oaks Corners are in the files of author Mark Staker.

[14] See scholar Richard L. Anderson’s brilliant and well-researched piece in which he presents an 1818 revival in Palmyra as the possible unusual excitement of Joseph’s memory: Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Joseph Smith’s Accuracy on the First Vision Setting: The Pivotal 1818 Palmyra Camp Meeting,” in Exploring the First Vision, ed. Samuel Alonzo Dodge and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2012), 91–169.

[15] A portrait of Roberts painted twenty years later hangs at DePauw University near where he and his wife are buried.

[16] Conable, History of the Genesee Annual Conference, 159.

[17] Conable, History of the Genesee Annual Conference, 159.

[18] See Conable, History of the Genesee Annual Conference, 159.

[19] Davis Dimock to George Peck, 19 September 1819, George Peck Correspondence, folders 1819, 1820, and 1821–1824, box 1, George Peck Papers, Syracuse University. George Peck kept copies of the letters he sent to the Baptist Reverend Davis Dimock and kept the originals of letters he received in return from Dimock and from Presbyterian minister Gideon Judd that document the debate. The collection of letters is as follows: Peck to Dimock, 30 August 1819; Dimock to Peck, 19 September 1819; Peck to Dimock, 5 October 1819; Gideon N. Judd to Peck, 1 December 1819; Peck to Dimock, 18 February 1820; Peck to Dimock, 2 May 1820; and Peck to Dimock, April 1821. These letters are cited in this article with permission of Syracuse University Special Collections.

[20] Peck to Dimock, 19 November 1819.

[21] See Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury, The Doctrines and Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church in America (Philadelphia: Henry Tuckniss), 1798.

[22] Peck to Dimock, 30 August 1819.

[23] Dimock to Peck, 18 February 1820.

[24] Peck to Dimock, 30 August 1819.

[25] See Coke and Asbury, Doctrines and Discipline, 20–22. The formal volume outlined baptism as a sign of regeneration and new birth. But each section includes a summary of a few scriptures with references, and one of them does mention baptism unto repentance. However, the public discourse apparently emphasized the content of the written material in the volume rather than the reference material. Doctrines and Discipline outlined baptism and the Lord’s Supper as the two sacraments instituted by Jesus Christ. In his debate with Dimock, Peck generally referred to the Lord’s Supper as the Eucharist, but Dimock referred to it as the sacrament, and Peck sometimes used that term also. But the volume also acknowledged that the church had instituted five more sacraments, including marriage.

[26] Joseph D. McPherson, “Historical Support for Early Methodist Views of Water and Spirit Baptism,” Asbury Journal 68, no. 2 (2013): 34.

[27] See Matthew 26:28; Mark 1:4; Luke 1:77; 3:3; 24:47; Acts 2:38; 10:43; Romans 3:25.

[28] McPherson, “Historical Support for Early Methodist Views,” 34.

[29] Gideon N. Judd to George Peck, 1 December 1819.

[30] See Gideon N. Judd, “Sermon CCCCXCVII The Magnanimity of the Christian Spirit,” American National Preacher 23, no. 4 (April 1849): 77–88.

[31] Peck to Dimock,**Dimock to Peck* 18 February 1820. One of the ministers addressed in the letter was Edward Panes Esq. (Edward Paine) of Waterford, Pennsylvania, who was the friend of the Pecks that drowned while trying to cross the Susquehanna River on his way to a conference on 8 July 1820.

[32] George Peck to Davis Dimock, 2 May 1820.

[33] George Peck to Davis Dimock, April 1821.

[34] Dean Jessee, “The Early Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” BYU Studies 9, no. 3 (1969): 279; or see “Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” https://

[35] Joseph Smith, History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2], p. [1], https://

[36] George Peck, 5 June 1821 Sermon “From the Time at My Station,” Peck Writings Miscellaneous 1821–1861, George Peck Papers, Syracuse University.

[37] Durfey Chase Account Book, Ledgers Box #2, Ontario Historical Society, Canandaigua, New York. No entries before this time addressed religion in the ledger, and the only entry after this period was that of George W. Smith, who was kicked by a horse at camp meeting on 19 June [1826?].

[38] Lemuel Durfee Account Book Ledgers Box #2, Ontario Historical Society, Canandaigua, New York.

[39] See Milton V. Backman Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision: The First Vision in Its Historical Context (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971), in which the author explores in detail the revival culture of western New York. Joseph Smith’s language in expressing the questions he took with him in prayer included the notion of joining a congregation. He said during an interview, “I kneeled down, and prayed, saying, ‘O Lord, what Church shall I join.’” Interview, 21 August 1843, extract, p. [3], https://any membership in any church.” Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1844–1845, p. [6], bk. 2, https://

[40] Harrington W. Holden, John Wesley in Company with High Churchmen (London: Church Press, 1869), 50.

[41] A Traveller, “Messrs. Editors,” Wayne Sentinel, 7 April 1826, 2.

[42] See Palmyra of the Past #VII, Old Newspapers file, Kings Daughters Library, Palmyra, New York. Thomas L. Cook, Palmyra and Vicinity (Palmyra, NY: n.p., 1930), 251–52. Kyle Walker, in his thorough examination of recollections of the First Vision by Joseph Smith’s family, notes that Mary Salisbury Hancock recorded hearing about the revivals from her grandmother Katherine Smith Salisbury, Joseph’s younger sister. Katherine would likely have visited some of these Methodist revivals during the 1820s with her family. She described a revival in the spring of 1820 as taking place “in a beautiful grove near by.” Kyle R. Walker, “Smith Family Recollections of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” Journal of Mormon History, forthcoming, 2021. In March the grove would have been bare and snow still on the ground, but it would still have had the beauty of early spring.

[43] Andrew Peck to George Peck, 11 March 1820.

[44] Authority for Methodists primarily meant one could speak or expound on doctrine as God would have it done, which supported the claims that one denomination’s doctrine was more correct than another’s. Methodist circuit rider Benajah Williams, for example, preached in Palmyra and in the surrounding areas of the district in 1820 and noted in his journal, on a later date, how preacher George Lane had a powerful influence on the teaching in their district. “Br. Lane Exhorted and spake on Gods method in bringing about Refformations[. H]is word was with as from the authority of God.” Benajah Williams, Journal, 15 July 1829, 127 (photocopies in the files of Mark Staker). For another example of this perspective, see George Peck, Early Methodism, 398. But doctrine was not the only issue influenced by authority. Authority to baptize was also debated during the revivals of the era, although it was not specifically mentioned in the Peck-Dimock letters. Detailed arguments primarily appeared in print almost a decade after the 1819–1820 debates and offer clues as to what may have been argued in the Genesee District. One of the earliest published Methodist references appeared in a periodical that included a fictional argument between a Baptist elder, a Methodist doctor, and a Methodist priest. The Methodist priest challenged a Baptist named Elder C.:

Pr[iest]. How came you to re-baptize sister Waters, Elder C.?

Eld[er]. My reason for “re-baptizing,” as you call it, was this: I did not consider her baptism valid, because I understood that you, yourself, sir, had not been baptized by a person who himself had been immersed by proper authority.

Doct[or]: What do you call proper authority?

Eld: That authority which can be traced by regular succession up to John the Baptist.

Pr. Oh, yes, I remember having seen in the village of Sing Sing, some years ago, an advertisement of a certain work, said to be written “by a regular descendent of John the Baptist.”

This may have been a reference to the already famous Sing Sing prison that had opened a little north of New York City in 1825, perhaps implying that crooks and swindlers would make a claim of connection to John the Baptist. But, pushing the point even further, the Methodist article then challenged the authority of John the Baptist altogether.

Pr[iest]. Admitting that you could prove a “regular succession” from John the Baptist, are you not aware that even then your authority would be questionable.

Eld[er]. I am not aware of it.

The preacher then took out of his trunk his pocket Testament, and turning to the nineteenth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, read as follows: [reads Acts 19:1–5 about those being baptized unto John’s baptism needing to be baptized again in the name of Jesus Christ]. . . . From hence, said the preacher, I should infer, that John’s baptism was not the Christian baptism, as it is very evident that St. Paul did not acknowledge the authority of John, nor consider his baptism valid in the Christian sense of the term. (“Cottage Dialogues,” Christian Advocate and Journal, and Zion’s Herald 2, no. 38 (23 May 1828): 149)

The article left many questions unanswered. Did authority for Elder C. come through baptizing in the same manner as John the Baptist? Did “regular succession” mean that authority came through ordination by someone who, in turn, had received authority from ordination by someone who had received authority in the same manner, all the way back to John the Baptist?

Arguments over authority to perform baptisms in the Susquehanna Valley became heated not long after George Peck left the district. An Anglican in Montrose, where Davis Dimock led the Baptists, claimed authority to continue in a line of succession back to the Apostle Peter and dismissed other denominations in the valley. “Controversial,” Susquehanna Register, 13 April 1832, 1. There was likely controversy in other parts of the Genesee District as well. If Peck had read the writing of founder John Wesley, then Peck knew that Wesley and his associates initially encouraged their followers to receive the sacraments within the Anglican Church while gathering and worshipping within their newly developing communities. Wesley insisted, “We believe it would not be right for us to administer either Baptism or the Lord’s Supper unless we had a commission so to do from those Bishops whom we apprehended to be in a succession from the Apostles.” Holden, John Wesley in Company, 50. Methodists in the nineteenth century believed Wesley received this authority from the Greek Orthodox bishop Erasmus of Arcadia during a visit to London in 1763; see Richard Joseph Cooke, The Historic Episcopate: A Study of Anglican Claims and Methodist Orders (New York: Eaton and Mains, 1896) 131, 140–45, 148, 151–55. This authorized John Wesley to act independently of the Anglican Church, they believed, though not everyone agreed that the ordination had occurred or that Wesley held proper authority. When John Wesley ordained Dr. Coke a bishop to preside in North America, Wesley’s brother Charles famously chastised John in verse, saying:

How easy now are Bishops made

By man or woman’s whim;

Wesley his hands on Coke hath laid,

But who laid hands on him?

(Cooke, Historic Episcopate, 52)

George Peck believed Wesley eventually “abandoned” the idea of apostolic succession and viewed all bishops from the original organization of the Church up to his day as holding equal authority that had been passed on through regular ordination and that a bishop was authorized to direct all activity in the church. See George Peck, Early Methodism, 2. (Today’s United Methodists argue that “bishops are not ‘ordained’ as bishops, but are clergy elected and consecrated to the office of bishop. . . . ‘Any clergy member of an annual conference is eligible to be elected a bishop’”; http://

But while George Peck saw all authority to direct affairs in the church as residing with bishops, he also said that bishops who had true authority exhibited the “signs of an apostle.” The bishop who directed affairs in America had (1) divine authority, (2) seniority of his ordination in America, (3) an “election” and confirmation of his position by the Methodist General Conference, (4) ordination by others who held authority, and (5) the “signs of an apostle.” These signs were considered miracles of various types—especially healings—because confirmation authority was had of God. It was in this context that Peck occasionally referred to his fellow circuit riders as “apostles,” or, in the context of an old friend after many years on the circuit, as an “old apostle.” Peck, Early Methodism, 205, 261 (see page 281, in which Peck argues that one must be ordained by three individuals holding the same office, a belief also held officially by the Orthodox Church and others but one that does not fit with the early Methodist understanding that an Orthodox priest alone ordained John Wesley.)

George Peck was consistent in his discussion of the process of passing on authority in his later writings as well and described the process as being “elected,” “confirmed,” and then “ordained.” See George Peck, The Life and Times of George Peck, D.D. (New York: Nelson and Phillips, 1874), 32, 73, 116. Peck’s language suggested a process that began with God but was ratified by the membership and then solidified by an individual holding authority in the Methodist church.