A Contextual Background for Joseph Smith's Last Known Recounting of the First Vision

Quinten Zehn Barney

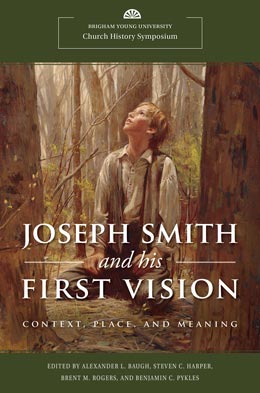

Quinten Zehn Barney, “A Contextual Background for Joseph Smith's Last Known Recounting of the First Vision,” in Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context, Place, and Meaning, ed. Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin Pykles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 129‒46.

Quinten Zehn Barney is an independent scholar and an instructor in Seminaries and Institutes of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

In the October 2019 general conference, President Russell M. Nelson designated the year 2020 “a bicentennial year,” it being “exactly 200 years since Joseph Smith experienced the theophany that we know as the First Vision.”[1] He went on to suggest that in preparation for the upcoming April general conference, members of the Church might consider reading afresh Joseph Smith’s account of this event as recorded in the Pearl of Great Price and further invited them to “select [their] own questions” and “design [their] own plan[s]” for study.[2] In addition to the 1838 account referred to by President Nelson, there are at least three other known firsthand accounts and five known contemporary secondary accounts of the First Vision.[3] While each of these accounts adds its own unique perspective and detail to this sacred and founding event in the restoration of the gospel, this chapter focuses on exploring the contextual background of the last of the secondary accounts, which was written down by a German-Jewish convert named Alexander Neibaur.

Unsurprisingly, the contextual background of Neibaur’s account of the First Vision has remained largely unexplored, with scholars instead choosing to focus their attention on the content of the account.[4] While the content of Neibaur’s account is indeed both rich and unique, it cannot be fully appreciated without a proper understanding of its context. Because of this, I have chosen several contextual questions to be the emphasis of this study. Specifically, I will explore (1) the provenance of the Alexander Neibaur journal, (2) the challenges with dating its account of the First Vision, (3) and the potential factors that may have prompted Joseph Smith to recount his first visionary experience to Neibaur in May of 1844.

Alexander Neibaur and His Account of the First Vision

Before I present the Neibaur account, a brief consideration of its author is in order. Born to Jewish parents in Europe in 1808, Alexander Neibaur began training as a Jewish rabbi when he was a child. However, after several years, he abandoned that route and chose instead to study dentistry at the University of Berlin.[5] Upon leaving the university, he traveled around Europe for several years before finally settling down in Preston, England, to practice his profession. There he met his wife, Ellen. The two had been married several years before they learned of some American ministers who had recently arrived and were said to be carrying a sacred book with them.[6]

Upon meeting with these missionaries in the summer of 1837, Neibaur was quick to embrace the message of the restored gospel. “The story of his conversion is,” as one author put it, “full of interest,” and Neibaur was later baptized by Isaac Russell in the River Ribble in April 1838.[7] A few years later, the Neibaurs traveled aboard the ship Sheffield among some of the early Saints who were called to emigrate from England to Zion.[8] After Neibaur arrived in Nauvoo in the spring of 1841, he built his home on Water Street near the banks of the Mississippi River, just a few blocks east of the Prophet’s home. While living here, Neibaur became close friends with Joseph Smith. Under the private tutelage of Neibaur in Nauvoo, the Prophet was able to continue his study of Hebrew that he had begun in Kirtland with Joshua Seixas. Some have suggested that it was during one of these language tutoring sessions on 24 May 1844 that the Prophet Joseph Smith chose to share the story of his First Vision with Neibaur, which Neibaur describes in his journal as follows:

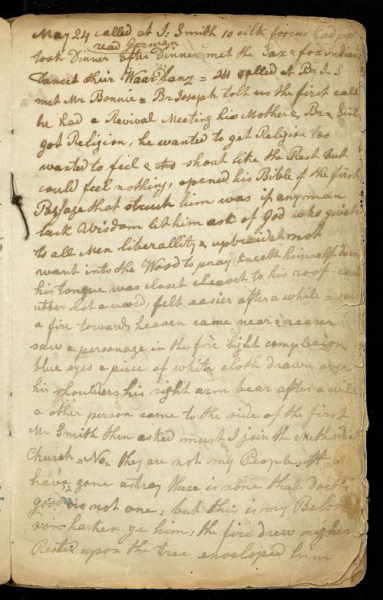

24 called at Br J= S met Mr Bonnie= Br Joseph tolt us the first call he had a Revival Meeting his Mother & Br & Sister got Religion, he wanted to get Religion too wanted to feel & shout like the Rest but could feel nothing, opened his Bible the first Passage that struck him was if any man lack Wisdom let him ask of God who giveth to all Men liberallity & upbraidet not went into the Wood to pray kneelt himself down his tongue was closet cleavet to his roof— could utter not a word, felt easier after a while= saw a fire towards heaven came near & nearer saw a personage in the fire light complexion blue eyes a piece of white cloth drawn over his shoulders his right arm bear after a w[h]ile a other person came to the side of the first Mr Smith then asked must I join the Methodist Church =No= they are not my People, th all have gone astray there is none that doeth good no not one, but this is my Beloved son harken ye him, the fire drew nigher Rested upon the tree enveloped him [illegible] comforted Indeavoured to arise but felt uncomen feeble= got into the house told the Methodist priest, said this was not a age for God to Reveal himself in Vision Revelation has ◊ ceased with the New Testament.[9]

The above account prompts many potential avenues for discussion. I will begin by reviewing its provenance, including how this private journal entry came to be so widely known and available both online and in print to a worldwide audience of Latter-day Saints.

Provenance of the Neibaur Journal

As mentioned previously, the First Vision account recorded by Alexander Neibaur was written down in his journal under the date of 24 May 1844. This journal is the only one that is known to have belonged to Alexander Neibaur—it spans roughly twenty-two years of his life from February 1841 until April 1862.[10] When Neibaur passed away in December 1883, no written will and testament could be found, and while we can be certain that the journal remained in the family, it is not entirely clear who received it.[11] Eleven of his children were still alive, as was his second wife, Elizabeth, and all except one of the family lived within 150 miles of Alexander Neibaur’s home in Salt Lake City.[12] Research reveals that the journal was in the possession of Neibaur’s daughter, Rebecca Nibley, by 1923 and that she was showing it to select, interested individuals.[13] After Rebecca’s passing in 1928, we hear nothing of the journal again until her grandson, the late Hugh Nibley, turned it over to Joseph Fielding Smith for safekeeping in the Church Historian’s Office sometime before 1952.[14] It’s not entirely clear when Dr. Nibley was given possession of the journal, though he did note that it was the unexpected discovery of the First Vision account in his great-grandfather’s journal that prompted him to hand it over to the care of the Church History Department.[15]

After its donation to the Church, public access to Alexander Neibaur’s journal was restricted.[16] On this note, Leonard J. Arrington related this somewhat humorous story in his biography:

Hugh Nibley, famous biblical and Book of Mormon scholar at Brigham Young University, came to the library to see the diary of his [great-]grandfather, Alexander Neibaur—a diary that he had previously given to the Church Historian’s Office. Lund refused to let him see it because it was restricted material. Despite Nibley[’s] protestations that he’d only just given the diary to Lund, he was refused. Later I saw Nibley at the table copying from the diary. He explained that he had gone to the president of the church, who [had] instructed Lund to let him use it.[17]

Of course, now that the entire journal is available for online viewing through the Church History Library’s website, one needs no more than a casual perusal to understand why access to the physical journal is restricted. Clearly, the voyage from Liverpool, the sojourn in Nauvoo, the trek west to the valley, and additional years in Salt Lake City have all left their marks of wear on the journal. Its forty-five leaves, with their occasional rips and tears, are bound together and only just attached to the cover’s spine by means of a small string. The leather cover itself is cracked, wrinkled, and torn, revealing in some spots the cardboard backing beneath it.[18] Thus the hesitancy of the Church History Department to allow the journal to be handled by interested parties today is completely understandable.[19]

After being donated to the Church, the journal was microfilmed on 12 July 1960 at the request of La Veigh Savage Thomas, a great-granddaughter of Alexander Neibaur.[20] And, at least initially, access to its contents was limited to family members. For example, Sandra Tanner, upon learning of the contents of the Neibaur journal, wrote a letter to Joseph Fielding Smith requesting to see it. In response, she was informed that “private journals are filed in this office with the understanding that they will be made available to members of the family, but not to the general public.” He further added that “the furnishing of copies of journals also follows this ruling.”[21] While this was in fact an established policy, it was also understood that the Church Historian could at times make exceptions to this policy.[22] By 1965 a brief excerpt from Neibaur’s account of the First Vision had appeared in Paul R. Cheesman’s BYU master’s thesis, and several years later the full account became available to the general public in Milton V. Backman Jr.’s 1971 book, Joseph Smith’s First Vision.[23] Today, advancements in digital imaging and internet technology have made it possible for people all over the world to access high-quality images of Neibaur’s journal from cover to cover.

The Challenge of Dating Neibaur’s Account

Among the most interesting details of Alexander Neibaur’s journal entry on the First Vision is the dating of his entry for 24 May 1844. Consequently, Neibaur’s account has come to be known as the last known contemporary secondary account of the First Vision. On the surface, there seems to be nothing unusual that would cause anyone to question this dating, and scholars have generally assumed that after hearing the Prophet recount his experience Neibaur went home and wrote of it in his journal that very day.[24] Nevertheless, a broader look through Neibaur’s journal presents some challenges with this dating, including evidence that it may have been written down much later than has previously been supposed. Because a later dating would carry with it several important implications, it is worth examining the evidence for this claim.

I will begin by reviewing Neibaur’s journal-keeping habits. The first entry of his journal dates to 5 February 1841, when he is found boarding the Sheffield in Liverpool to come to the United States.[25] The seventy-three-day voyage from Liverpool to Nauvoo allowed Neibaur to write almost daily in his new journal—he missed writing only two days of the entire voyage.[26] Once in Nauvoo, Neibaur begins writing less and less frequently, no doubt because of the demands of life that came along with settling his family on the Illinois frontier. Only twenty-nine more entries were made in the remainder of 1841.[27] The year following, 1842, saw only eight entries, and not a single journal entry is recorded for 1843.[28]

The portion of Neibaur’s journal covering the year 1844 is where things begin to get complex, and even a bit out of order. A year having elapsed since his last entry, Neibaur begins this portion by writing the year “1844.” Immediately to the right of this, we see the important date of “June 27” written down, followed by “Joseph and Hyrum murdered in Carthage Jail.” The cramped and slanted appearance of this entry, along with its darker pigment and smaller handwriting, suggests that it was scribbled in at a later time than the other 1844 entries on the page.[29] Directly beneath the year 1844, and in the same density of ink, we see the more probable first entry of 1844, dated to 18 January. This entry, in which Neibaur describes being ordained under the hands of Willard Richards and John Taylor, is followed by several other brief and difficult-to-read entries from around this time.[30]

Top and bottom: Alexander Naibaur journal, pages 20 and 25 respectively, MS 1674. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Top and bottom: Alexander Naibaur journal, pages 20 and 25 respectively, MS 1674. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Following these entries, the journal finally arrives at a 24 May entry, though it is given the year 1845, rather than 1844. This entry goes on to describe the capstone ceremony of the Nauvoo Temple, which did in fact take place that morning in 1845.[31] It is not until several pages later—after some of Neibaur’s transactional business, a few misplaced entries on the weather, and some Hebrew poetry—that we jump back a year to Neibaur’s 24 May 1844 account of the First Vision.[32] What’s more, Neibaur once again continued writing fairly consistently from this point all the way to the burial of Joseph and Hyrum on the 29th of June.[33] Following this entry on the burial, his journal picks back up in September 1845 and continues chronologically from there.[34]

What can be made of this confusing arrangement of journal entries? A case could be argued that Neibaur may have simply recorded his 24 May 1845 entry on the wrong page by accident, and were it removed, the rest of the entries would still flow quite naturally in chronological order. However, this theory ignores the unique placement of Neibaur’s first entry on the martyrdom. The fact that this entry recording the martyrdom is not included in chronological sequence on the page strongly suggests that Neibaur’s 1845 entry on the capstone ceremony had already been written down on the page before he decided to go back and add a note on the martyrdom. The fact that Neibaur would take the time to go back and write about the martyrdom here further implies that his second entry on the martyrdom several pages later had not yet been written down at that time.

Of further note is that Neibaur was not one to leave much blank space in his journal. A look at each page of his journal reveals that he never left space at the bottom of a page for any more than an additional line or two of writing, yet even these instances are extremely rare.[35] If the portion of his 1844 entries that begin with the First Vision account were in fact written before his 1845 entry on the capstone ceremony, readers would be left wondering as to why he chose to flip several leaves in his journal and begin his 24 May 1844 entry at the top of a brand new page, rather than continue on the page where he had previously left off.

It is of further interest that Neibaur, having grown more sparse in his journal keeping over time, would suddenly begin a consistent stretch of entries detailing such significant events as the First Vision, contentions between Joseph Smith and William Law, visits of officials to and from Carthage, the destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor press, the martyrdom at Carthage, and a concluding entry on Joseph’s and Hyrum’s burial. Unlike many of his previous entries, this portion of his journal does not include any of the trivial or mundane happenings in Nauvoo nor entries on the weather. Rather, the focus of nearly every entry in this portion of Neibaur’s journal is directly on the Prophet Joseph Smith and those relevant factors that led up to his martyrdom.[36] Such a focal emphasis would seem rather odd had these entries actually been recorded on the same day they occurred. More likely is the possibility that Neibaur, recognizing that his first entry on the martyrdom did little justice to all the significant happenings near Nauvoo at that time, decided to flip several pages and write both retrospectively and intentionally, focusing on preserving as best as possible his final memories of his dear friend and prophet, Joseph Smith. Based on the evidence above, as well as that from surrounding entries, it is likely that this reminiscence on the First Vision was written down sometime between 24 May and 10 September 1845.

I hasten to add that assuming a later date for the writing of Neibaur’s account of the First Vision need not imply Neibaur’s account to be any less reliable. The reality is that the process of remembering is very complex, and it is a false assumption that memories simply deteriorate with the passing of time.[37] Indeed, as Steven C. Harper has suggested, “time may be an enemy to memory, but it is also its most significant ally.”[38] One important study has even gone so far as to demonstrate that some memories are “so permanent and largely immutable that [they are] best described as archival.”[39] The same study found that one of the primary factors in one’s ability to successfully recall such memories is a high level of emotion attached to them.[40] In the case of Neibaur, hearing of such a sacred event as the First Vision from the Prophet himself in such an intimate setting would certainly have produced the heightened emotion necessary to create a strong and lasting impression in Neibaur’s mind.

What Prompted the 24 May 1844 Recounting?

It has been said that “each document that preserves a contemporary account of the Prophet’s First Vision was directed toward a particular audience” and that “striving to understand the objective that Joseph Smith had in mind as he communicated with each audience helps todays’ readers appreciate the particular details uniquely conveyed in each of [the accounts of the First Vision].”[41] For the most part, the question of what prompted Joseph to recount his vision to Neibaur has been largely unexplored. Hugh Nibley had been under the impression that Neibaur had “asked” Joseph Smith to share the account and “cross-examined [him] on every minute detail” until the Prophet had “satisfied him promptly and completely.”[42] Neibaur’s journal, however, gives no such evidence that this was the case. Nevertheless, Neibaur does record a critical detail in this account that may have played a key role in the retelling of the First Vision story that morning—specifically that Neibaur, after calling at Joseph Smith’s home, met a man there that he refers to only as “Mr. Bonnie.”[43]

Several historians have suggested that the “Mr. Bonnie” Neibaur refers to is Edward Bonney, a recently ordained member of the Council of Fifty who had just returned to Nauvoo with his family from Indiana.[44] Though Edward’s older brother had also been living in Nauvoo at this time, there is strong evidence to suggest that Neibaur was referring to Edward and not his brother.[45] Joseph Smith makes it a point to note Edward Bonney’s return to Nauvoo in his journal on 19 May, and Bonney is named several other times in the Prophet’s journal thereafter.

Significantly, although Edward had been admitted to the Council of Fifty in April, there is no indication that he was ever baptized into the Church. In fact, shortly after Bonney had returned to get his family in Indiana, a council meeting was held in which Joseph Smith “made some remarks on the absence of brother Edward Bonney the cause of absence, and his good feelings towards the council &c.” The council minutes continue,

[Joseph Smith] then went on to say that for the benefit of mankind and succeeding generations he wished it to be recorded that there are men admitted members of this honorable council, who are not members of the church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, neither profess any creed or religious sentiment whatever, to show that in the organization of this kingdom men are not consulted as to their religious opinions or notions in any shape or form whatever.[46]

By his own account, Bonney later claimed to be not “much of a religionist,” which fact was apparently weighing heavily upon the mind of the Prophet at this time.[47] Although making clear his respect for the beliefs or disbeliefs of all men, including the three nonmembers in the Council of Fifty, Joseph continued, “When I have used every means in my power to exalt a mans mind, and have taught him righteous principles to no effect—he is still inclined in his darkness, yet the same principles of liberty and charity would ever be manifested by me as though he embraced it.”[48] So strong were the Prophet’s feelings on this matter that the record goes on to say that while he was speaking, “he felt animated and used a 24 inch gauge or rule pretty freely until he broke it in two in the middle.”[49]

The council minutes may offer some potential background for Alexander Neibaur’s journal entry on the First Vision. The fact that he records meeting Mr. Bonney immediately after calling at Joseph’s home tells us that Neibaur was not the only one to hear of the First Vision that day. Indeed, Neibaur specifically writes that Joseph “told us” of his First Vision. While Joseph did share his First Vision experience publicly on several occasions, the historical records suggest that a frequent denominator in his more private recountings was the presence of someone who was unfamiliar with or otherwise unconvinced of the veracity of his experience.[50] Thus there is a strong possibility that the 24 May 1844 recounting of the First Vision, though recorded by Neibaur, may have been given primarily for the benefit of the Prophet’s nonreligious friend and Council of Fifty member Edward Bonney.

Conclusion

As with any other historical narrative, Neibaur’s account of the First Vision is both informed and enriched through a better understanding of its context. None of the First Vision accounts available today were created in a vacuum. Piecing together clues to help us understand the path Neibaur’s account took to become so widely available today, why and when Neibaur chose to record it, and the factors relating to Joseph’s purpose in recounting his visionary experience at this time is a worthwhile pursuit that can lead to a greater appreciation for this historical and life-changing event.

In addition to the wonderful contributions Neibaur’s account makes to our understanding of the First Vision, may I conclude with one final and important observation: Alexander Neibaur not only recorded an account of the First Vision in his journal—he believed the account. Toward the end of his life he wrote, “I do not pen these lines, but for the gratification of my posterity, bearing to them and to all who may read these few lines my testimony that Joseph Smith was a prophet of the Lord.”[51] Though unbeknownst to Neibaur at the time, his record of the First Vision, as well as his testimony of the Prophet Joseph’s calling, would one day stand as a remarkable witness to all the world that God still speaks to his children and has restored his gospel in these, the latter days.

Notes

[1] Russell M Nelson, “Closing Remarks,” Ensign, November 2019, 122.

[2] Nelson, “Closing Remarks,” 122.

[3] The term firsthand accounts here refers to those accounts that were recorded by or under the direction of Joseph Smith, while contemporary secondary accounts refers to those accounts that were recorded during Joseph Smith’s lifetime by contemporaries who had heard him speak of his visionary experience. Each of these accounts can be found via the Joseph Smith Papers website. See “Primary Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision of Deity,” josephsmithpapers.org/

[4] Most studies on the First Vision include no more than a paragraph of biographical introduction before sharing the content of Neibaur’s account. For example, see Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 65; James B. Allen and John W. Welch, “The Appearance of the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith in 1820,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations: 1820–1844, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 50; Dan Vogel, comp., Early Mormon Documents (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1996), 1:189; Milton V. Backman Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision: The First Vision in Its Historical Context (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971), 177.

[5] The absence of Neibaur’s name in the matriculation records during the years he would have attended the University suggests that he attended as a Gasthörer, or guest student. See Die Matrikel der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin 1810-1850, ed. Peter Bahl and Wolfgang Ribbe (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010): 1:LIII. However, while the matriculation records are complete for this period, the Gasthörer record book is not, making it impossible to tell whether Neibaur attended as such.

[6] For a more detailed overview of Neibaur’s early life, see Fred E. Woods, “A Mormon and Still a Jew: The Life of Alexander Neibaur,” Mormon Historical Studies 7, no. 1 (2006): 22–34.

[7] Susa Young Gates, “Alexander Neibaur,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine 5, no. 2 (April 1914): 53–55.

[8] See Saints by Sea: Latter-day Saint Immigration to America: Liverpool to New Orleans, 7 February 1841–30 March 1831, https://

[9] Alexander Neibaur Journal, 24 May 1844, Church History Library, Salt Lake City (hereafter CHL). Original spelling and punctuation have been preserved. This entry is actually the second entry that is dated 24 May 1844, though the events Neibaur described in his first entry for that day, including the Sac and Fox Indians dancing their war dance, can be corroborated with other records to show that the first entry should have been dated 23 May in Neibaur’s journal. See Willard Richards Journal, 23 May 1844, in The Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, 3:257–59 (hereafter JSP, J3).

[10] The current condition of the journal shows the pages separated from the covers, making it impossible to tell if any pages after this date are missing.

[11] See Neibaur Family Estate Records, CHL.

[12] See Neibaur Family Estate Records, CHL.

[13] See Leon L. Watters, The Pioneer Jews of Utah (New York: American Jewish Historical Society, 1952), 24n4. Watters notes, after citing several entries from Neibaur’s journal, “Ms. shown to the author by Mrs. Charles W. Nibley in 1923. The diary is now in the office of the Church Historian, Salt Lake City.” Some of the contents of the journal were known to Susa Young Gates at least nine years earlier, when she published a brief biographical sketch of Alexander Neibaur, which also referred to his practice of faithful journal keeping. Though it is not certain how Gates obtained access to the journal, she was both a friend and associate of Rebecca Neibaur Nibley, suggesting that Rebecca may have been in possession of her father’s journal as early as 1914.

[14] Watters notes in his 1952 publication that Neibaur’s journal was currently in the Church Historian’s Office; see Watters, Pioneer Jews of Utah, 24n4. In a letter to Sandra Tanner, dated 8 March 1961, Hugh Nibley stated that he had “handed the book over to Joseph Fielding Smith and it is now where it belongs—in a safe.” Leonard J. Arrington, who was “researching consistently for the summers of 1946, 1947, 1948, and 1949,” implies that the journal was donated sometime around these dates. Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 15–16.

[15] See Hugh Nibley letter to Sandra Tanner, 8 March 1961, in Pauline Hancock, The Godhead: Is There More Than One God? Did Joseph Smith See the Father and the Son in 1820? (Independence, MO: Church of Christ, n.d.), 12–13. It is interesting that although Nibley had direct access to his great-grandfather’s account of the First Vision for some time, and even referenced it on several occasions, he never seems to have quoted from it. Indeed, it was Hugh Nibley’s belief that Neibaur’s First Vision account constituted part of a private conversation between him and the Prophet and was too sacred to be published to the world. See Hugh W. Nibley, “Censoring the Joseph Smith Story,” Improvement Era, July 1961, 522; reprinted in Nibley, Tinkling Cymbals and Sounding Brass (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 63–64.

[16] In a memo dated 2 May 1949, Church Historian and Recorder Joseph Fielding Smith informed stake presidents, bishops, and other Church leaders of the policy that private journals filed in the Church Historian’s Office would be made available only to family members and that any others who wished to view such journals would need special permission from the Church Historian. See Joseph Fielding Smith to the Presidents of Stakes, Bishops of Wards, Presidents of Missions, and Heads of Auxiliary General Boards, 2 May 1949, CHL.

[17] Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian, 16. Leonard Arrington shared this memory as if it had taken place during the time when he was “researching consistently for the summers of 1946, 1947, 1948, and 1949.”

[18] For a more detailed description on the condition of the journal, see Quinten Barney, “Joseph Smith’s Last Weeks,” Mormon Historical Studies 18, no. 1 (2017): 66.

[19] In reply to my request to view the journal, I was informed that “the original diary is extremely fragile, as you can see from the digitized images, so we are reluctant to have it handled”; personal email correspondence with archivist at the Church History Library.

[20] The microfilm date, along with the name of the requester, is found on the few pages that precede the journal microfilm copy of Alexander Neibaur Journal, 1841 February–1862, CHL. According to familysearch.org, La Veigh is the great-granddaughter of Alexander Neibaur through his oldest daughter, Margaret.

[21] Joseph Fielding Smith to Jerald and Sandra Tanner, 13 March 1961, in Hancock, Godhead, 13. Sandra’s mother-in-law, Helen Tanner, also demanded access to the journal. See Helen Tanner Letter, Salt Lake City, Utah, to David O. McKay, 23 April 1961, CHL, MS 3793. Citing Nibley’s experience of being refused to see the journal, Helen accused the Church of not following its own policies as a result of an attempt to hide Neibaur’s First Vision account. However, Nibley’s account may simply have been an anomaly, since a microfilmed copy had already been provided for a great-granddaughter of Neibaur in July 1960.

[22] See Joseph Fielding Smith to the Presidents of Stakes, Bishops of Wards, Presidents of Missions, and Heads of Auxiliary General Boards.

[23] See Backman, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 177.

[24] See Nibley, “Censoring the Joseph Smith Story,” 522 (in Nibley, Tinkling Cymbals, 63–64); James B. Allen, “The Significance of Joseph Smith’s ‘First Vision’ in Mormon Thought,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 1, no. 3 (1966): 43; Matthew B. Christensen, The First Vision: A Harmonization of 10 Accounts from the Sacred Grove (Springville, UT: CFI, 2014), 9; Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 1:189.

[25] See Alexander Neibaur Journal, 1.

[26] Entries are missing for 12 February and 5 April 1841.

[27] These include daily entries for the remainder of April, ten entries in May, three in June, one in July, two in August, one in October, and one in November.

[28] Two very brief entries were made for 7 May 1842, though they are counted as one entry here.

[29] The line separating his 1844 entries from his 1842 entries also appears to have been written at this time. News of the martyrdom didn’t reach Nauvoo until the next morning. Since Neibaur was in Nauvoo at the time of the martyrdom, this entry was written sometime after 27 June, 1844.

[30] A typescript of the journal in the Church History Department suggests these lines read “9 br 11 the letter from my parents,” which is a likely reading. This might suggest that a letter from Neibaur’s parents was inserted in his journal here and has since been lost. Importantly, there has been some confusion as to the dating of the events recorded in Neibaur’s 18 January entry. In his entry, he records being ordained under the hands of Willard Richards and John Taylor to become one of the seventy. While the year “1844” is written directly above this entry, Neibaur would later record that he was ordained under the hands of these two brethren in 1843, rather than 1844. See Alexander Neibaur, Autobiographical Sketch, “Biographical Record of the 5th Quorum of Seventies,” CHL. However, in the License Record Book, Willard Richards recorded that Neibaur received an elder’s license on 18 January 1844. See “License Record Book,” p. 120, josephsmithpapers.org/

[31] Whether or not Neibaur attended the ceremony is unclear, though given the grand significance of the event, it is difficult to imagine him missing it. Some details of the capstone ceremony can be found in the Nauvoo Neighbor, 28 May 1945, 2.

[32] At the top of one of the pages containing Neibaur’s transactional business, he recorded journal entries detailing the weather for March 15th through 20th of some unknown year. However, it is clear that they do not belong to 1844 because Wilford Woodruff’s detailed descriptions of the weather in Nauvoo during that time contradict Neibaur’s descriptions in several instances. For example, Woodruff records a snowstorm on March 17th, whereas Neibaur writes “fine warm weather.” On the 20th, Woodruff tells of a “Cold North wind” and “snow and hail storm until 10 o clok [sic]. Continued cloudy & cold wind from the North until 3 o clock[,] was plesant [sic] during the remainder part of the day,” while Neibaur records, “Cloudy morn. about 8 fine sunny.” The discrepancies with Woodruff’s journal suggest Neibaur is describing the weather in a year other than 1844. See Wilford Woodruff Journal, 17 and 20 March 1844, CHL.

[33] There are only ten entries missing from the thirty-seven-day span of 24 May–29 June 1844.

[34] At the bottom of the page following the second portion of his 1844 entries, Neibaur includes three very brief entries from 1846, including the dates of his endowment and sealing. The inclusion of these dates is intriguing since the top of the next page begins chronologically again from 10 September 1845. As argued below, it is likely that Neibaur intended the second portion of his 1844 entries to stand as a separate, retrospective portion of his journal, and his 1845 entries would thus represent where he began writing again from his present perspective. This would explain why there would have been a blank space after his 1844 entries for him to come back and later record significant ordinance work that he had failed to write in 1846.

[35] There are only a few pages in his journal where he could presumably have written 1–2 more lines, though none have as much space on them for writing as does the page of his 24 May 1845 account. The one and only exception is the page containing his Hebrew poem, though the writing is written sideways in the journal here and contains only the poem, written in large text.

[36] Nearly every entry in this portion of Neibaur’s journal (24 May 1844–29 June 1844) makes a direct reference to Joseph Smith, and the focus is clearly on the Prophet. For example, Neibaur includes entries such as “Preached from 1 Revel on the plurality of gods” and “trial before Sqr Wells a county magistrate on a charge of riot,” which are of course references to the Prophet preaching and being tried, not Neibaur. In another entry, Neibaur simply writes “saw him in the morning Preachet [sic] about false Br,” which further suggests a strong and intentional focus on the Prophet.

[37] See Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 95–96. For a more in-depth discussion on the topic of memory as it relates to accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, see Steven C. Harper, The First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[38] Harper, Memory and Mormon Origins, 40.

[39] Alice Hoffman, Archives of Memory: A Solider Recalls World War II (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990), 145.

[40] Hoffman, Archives of Memory, 145–46. Drawing upon his research on memory studies, Steven Harper further cites psychologists and neuroscientists that “confirm that ‘memory begins with an emotional association’ and that ‘emotionally intense events produce vivid memories.’” Edmund Blair Bolles, as quoted in Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 96.

[41] Allen and Welch, “Appearance of the Father and the Son,” 40.

[42] Hugh Nibley, The World and the Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1987), 23.

[43] Alexander Neibaur Journal, 23.

[44] JSP, Council of Fifty, Minutes, 74 (hereafter JSP, CFM). Edward’s older brother, Amasa, had been baptized years earlier and was also living in Nauvoo at this time.

[45] Joseph Smith’s journal mentions the name “Bonney” (or “Bonny”) in four instances during this time period but never gives a first name. However, the frequency with which the name appears in Joseph’s journal during this time period suggests that this Bonney is the “Edwa[r]d Bonney” mentioned in Willard Richards’s journal entry for 26 June 1844, in JSP, J3:315.

[46] JSP, CFM:97.

[47] Edward Bonney, Banditti of the Prairies, circa 1847–1849, [4–5]. Microfilm, CHL.

[48] JSP, CFM:100.

[49] JSP, CFM:101.

[50] Such appears to have been the case with Smith’s early recounting to the Methodist minister in New York, as well as in a later recounting to Robert Matthews, Erastus Homes, and David Nye White.

[51] Neibaur, Autobiographical Sketch.