Breck England, “An Undeviating Course: The Leadership Focus of Joseph and Hyrum,” in Joseph and Hyrum—Leading as One, ed. Mark E. Mendenhall, Hal B Gregersen, Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Heidi S. Swinton, and Breck England (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 125–44.

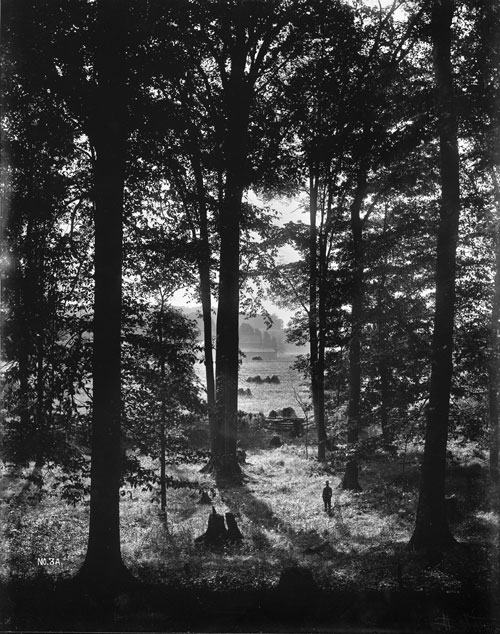

Referring to his experience in the Sacred Grove, Joseph said, "My soul was filled with love and for many days I could rejoice with great Joy and the Lord was with me." As a leader, Joseph Smith had one aim, one goal, one overarching purpose: to bring us back to the Savior. (The Sacred Grove, George Edward Anderson, circa August 13, 1907.)

Referring to his experience in the Sacred Grove, Joseph said, "My soul was filled with love and for many days I could rejoice with great Joy and the Lord was with me." As a leader, Joseph Smith had one aim, one goal, one overarching purpose: to bring us back to the Savior. (The Sacred Grove, George Edward Anderson, circa August 13, 1907.)

When Joseph Smith left the Sacred Grove, he had experienced as a mortal what is in the future for each of us—to be “taken home to that God who gave [us] life” (Alma 40:11). Joseph’s singular experience at the feet of the Father and the Son left him with an all-consuming mission: to return to that presence and to bring as many as would come with him.

Of the grove experience, Joseph said, “My soul was filled with love and for many days I could rejoice with great Joy and the Lord was with me.” [1] It was his love for the Lord he had seen and felt and heard that motivated him for the rest of his life. As a leader, Joseph Smith had one aim, one goal, one overarching purpose: to bring us back to the Savior.

In this chapter I will explore how Joseph and Hyrum Smith kept themselves and the Church focused on this goal. We will look at how they dealt with distraction and how they executed their mission with excellence.

The Problem of Focus

One of the hardest challenges leaders face inside and outside the Church is to maintain focus. Many leaders announce a strategy and then, distracted by the day-to-day demands of the job, fail to execute it. People without a crystallized sense of mission lose heart and drift away; going through the motions is not enough for them. Rudderless organizations fail.

A bishop I know came to the end of his assignment and confided to me that he wondered if he had made a difference. He had started out with great intentions, but five years later sacrament meeting attendance was roughly where it had been when he was called. Tithe paying and temple attendance had not changed. He had held hundreds of meetings, but to what end? I did not consider him a failure and assured him that he had made a tremendous difference in the lives of ward members. But I could not dispel his sense of having gotten lost in the minutiae of administration at the expense of the higher mission: to bring the members of his ward closer to the Savior.

In the world of business, leaders encounter the same problem or worse: they fail to achieve the goals they set for themselves. One study of public companies found that only 13 percent of them consistently met financial goals over the decade of the 1990s—one of the best-performing decades in business history. [2] Nine out of ten failed to grow their companies profitably. [3] According to former Kellogg School of Business professor Ram Charan, seven out of ten strategic initiatives eventually fail. The reason? It’s usually not for a lack of smarts or vision. “It’s bad execution. As simple as that: not getting things done, being indecisive, not delivering on commitments.” [4] Says Charan, “The greatest unaddressed issue in the business world today is the ‘execution gap’—the gap between setting a goal and achieving it.” [5] The penalties for weak execution are severe in the business world; by contrast, great dividends come from consistently meeting expectations.

Parents face the same challenge of maintaining focus on what really matters. We all know too well about the distractions that can drive out of family life the few simple daily devotions—prayer, meditation on the scriptures—that cumulatively bind a family to each other and to the Savior.

But what is behind this “execution gap”? What causes leaders—at church, at work, at home—to lose focus on their most important goals and fail to achieve them?

Lack of Clear Goals

One reason for failure is the lack of clear goals. An ongoing five-year survey sponsored by FranklinCovey Company has asked more than 250,000 respondents if they agree with this statement: “My organization has decided what its most important goals are.” A little more than half agree. But when they are asked to state the goals, fewer than 15 percent can do so. [6] What is the impact on an organization’s success when only about one in seven people can tell you what they are trying to achieve? Isn’t it purposeless meetings, endless debate about priorities, and wasted resources?

Does the same lack of clarity exist in the Church? Do bishoprics, stake presidencies, and auxiliary leaders have identifiable goals? Are meetings held without clear purposes or outcomes? Do Gospel Doctrine lessons have an objective, or are they too often wandering discussions? Do priesthood interviews and home teaching visits have a discernible purpose, or are they just to pass the time of day? Do fathers and mothers clearly teach that the family goal is exaltation in the celestial kingdom?

Lack of clarity leads to a tremendous waste of effort. Because people want to contribute to a meaningful purpose, if the organization fails to provide one they will find their own. As a result, they are very busy doing things that may or may not support the organization’s strategy.

An “Eye Single”

The Prophet Joseph Smith was unfailingly clear about his purpose: “Joseph’s governing passion was to have his people experience God.” [7] He often spoke of having “an eye single to the glory of God,” which is “to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” and “the welfare of the . . . covenant people of the Lord” (D&C 4:5; Moses 1:39; Mormon 8:15). The metaphor of the “eye single” is a powerful reminder of the need for focus; obviously an eye afflicted with double or triple vision cannot focus. Joseph’s own eye was fixed on what Alma called the “one thing which is of more importance than . . . all [else]” (Alma 7:7)—the Savior and his coming.

Church leaders, regardless of role, should have an “eye single” to this goal—bringing people to Christ. Elder Dallin H. Oaks has called this one of the “ultimate Latter-day Saint priorities”: “First,” he said, “we seek to understand our relationship to God the Eternal Father and His Son, Jesus Christ, and to secure that relationship by obtaining their saving ordinances and by keeping our personal covenants.” [8] Everything we do as Church leaders should measurably advance this goal.

Ironically, some observers have accused Joseph Smith of lacking focus, particularly in his later years. At Nauvoo, his urgent and disparate activities—building a city, leading the Nauvoo Legion, introducing doctrinal innovations, constructing the temple—strike some as evidence of a man “losing control of many affairs and perhaps of himself.” [9] But as the historian Ronald K. Esplin has said, “Such an assessment fails to take into account the religious goals, insights and understandings that influenced—almost compelled so many Nauvoo decisions”—principally, the goal of bringing the Saints to the Lord through the temple. “More than any other single thing, the focal point was the temple. In spite of his economic and political and military and civil involvements, Joseph Smith’s mission and his legacy were religious: religious power, insight, teachings, and ritual. And that mission centered on the magnificent structure on the hill.” [10]

Parents must also have an “eye single” to the goal of bringing the family to Christ. Too many families have actually lost this focus, often without realizing it. Joseph built a city not as an end in itself but in order to build a temple. Great parents do not simply raise children—clothing, feeding, educating, and entertaining them—they raise them to Christ. Elder Quentin L. Cook observes, “We are often unaware of the distractions which push us in a material direction and keep us from a Christ-centered focus. In essence we let celestial goals get sidetracked by telestial distractions.” [11]

Great leaders of any organization are totally clear on the ultimately important, “mission-central” goals. While any important goal might be worth achieving, an ultimately important goal must be achieved. Failure to achieve this goal renders any other achievements inconsequential. Thus, it is crippling to be distracted by six, eight, or ten—or more—important goals at once. Leaders do a mediocre job on many goals when they could do a great job on one or two ultimately important goals.

The Way Forward

Another reason organizations lose focus is a lack of clarity about the way forward. The goal might be clear, but how do we achieve it? It’s one thing to be fully committed to a goal; it’s another thing entirely to execute it with excellence. Elder Oaks observes, “There is great strength in being highly focused on our goals. We have all seen the favorable fruits of that focus. Yet an intense focus on goals can cause a person to forget the importance of righteous means.” [12]

Of course, Joseph Smith had the benefit of revelation to show him the way forward, and anyone who properly seeks the guidance of the Holy Ghost can enjoy similar direction. Still, the Lord expects us to work out the pathway for ourselves. President Thomas S. Monson has said, “Our Heavenly Father has given us life and with it the capacity to think, to reason, and . . . the ability to determine the path we will take, the direction we will travel.” [13]

For Joseph Smith, the way clearly led through the temple. In the temple, every step along the path, every covenant necessary for exaltation is clearly spelled out. “We need the temple more than anything else,” Joseph said. [14] Everything he did from the beginning of his ministry pointed to the temple because there the Saints would encounter the Savior and qualify for his presence. This is why, in Richard L. Bushman’s words, “temples became an obsession [for Joseph]. For the rest of his life, no matter the cost of the temple to himself and his people, he made plans, raised money, mobilized workers, and required sacrifice.” [15] In 1843 Joseph sent the elders to gather the Saints, and the purpose of the gathering was in turn to build the house of the Lord. “What was the object of gathering the . . . people of God in any age of the world?” he asked. “The main object was to build unto the Lord a house whereby He could reveal unto His people the ordinances of His house and the glories of His kingdom, and teach the people the way of salvation. . . . It is for the same purpose that God gathers together His people in the last days, to build unto the Lord a house to prepare them for the ordinances and endowments.” [16]

Thus the building of temples was Joseph’s primary concern. All of his business dealings, his locating of cities, his establishment of stakes—everything he did was in the service of providing a sacred place for the Saints to meet the Savior. A “stake” is a support for the center of the tent—the temple. Again in Bushman’s words, Joseph “concentrated holiness in one place, in a sacred city and its temple. . . . He conceived the world as a vast funnel with the city at the vortex and the temple at the center of the city.” [17]

Joseph’s greatest support and counselor, his brother Hyrum, well understood the primacy of the temple. When Joseph explained the purpose and pattern of the Kirtland Temple, Hyrum “could hardly contain his enthusiasm.” After Joseph designated the site, Hyrum ran to his mother’s house, picked up a scythe, and started off again. His mother, Lucy, stopped him and asked him where he was going. “‘We are preparing to build a house for the Lord,” he replied, “and I am determined to be the first at the work.’ Later, . . . Hyrum commenced digging a trench for the wall, he having declared that he would strike the first blow upon the house.” [18]

Hyrum and others also stressed the vital importance of the temple in a letter to the Saints: “Make every possible exertion to aid temporally, as well as spiritually, in this great work. . . . Unless we fulfill this command, . . . we may all despair of obtaining the great blessing that God has promised to the faithful of the Church of Christ.” [19]

In October 1843, Hyrum was assigned to manage the construction of the Nauvoo Temple. Stone was abundant, but the lack of money for glass and hardware had become crippling. Nothing could stop Hyrum from driving the construction forward, so he came up with an innovative solution:

Patriarch Hyrum Smith made a proclamation to the women of the Church, asking them to subscribe in money one cent each per week, for the purpose of buying the glass and nails for the Temple. He represented to them that by this means he would be able to meet all the requirements in this regard. He also gave a promise that all the sisters who would comply with this call should have the first privilege of seats in the Temple when it was finished. He opened a record of these contributions, which he kept, with the aid of Sister Mercy R. Thompson, until his death. . . . There was soon a great anxiety manifest among the sisters to pay their portion, and nearly all paid a year’s subscription in advance. [20]

For Hyrum, the temple had to be constructed. It was the sine qua non of the Church; the goal that must be achieved or nothing else much matters. He had to find a manageable way to drive the goal to completion, and he did so. The essence of leadership is to know what must be achieved (as opposed to what might be achieved) and then to find the most effective way to achieve it.

The leadership example of Joseph and Hyrum Smith should teach Church leaders that bringing people to Christ is their first priority—and that the way leads through the temple. So far from being just one priority among many, the temple should be the ultimate priority, the “main object,” as Joseph said. Everything leaders do in the Church should focus on helping the Saints to make and keep temple covenants. Youth conferences, Sunday School classes, Primary programs, family activities—unless they clearly lead to the temple and to Christ, their purposes might be questioned.

In business, it is equally important to identify the way forward. What are the logical steps to the ultimately important goal? What resources must be committed? What commitments must be made and kept in order to achieve the goal? What systems must be in place to serve the goal? Which activities will have the biggest impact on achieving the goal?

Fatal Distractions

The goal is clear, and the way forward has been defined—and now is the most dangerous time of all. How common is the following scenario? Leaders present the goal and the strategy, everyone applauds, and nothing changes. Weeks go by, months pass, and no one does much about the goal.

People don’t simply ignore the most important priorities. They support the priorities, but they get worn out by a whirlwind of demands. Drained by day-to-day urgencies, they often lack the energy required to pursue truly important goals. Going to the temple seems like just one more chore among many, particularly when other priorities demand more immediate attention. Social and business obligations or homework crowd out family home evening. The ultimately important goal often lacks the feel of urgency, so it is always at the mercy of “fatal distractions”—priorities that seem good in the moment but in the end rob time and energy from the most important priorities.

Distracted in this way, we become like the children of Israel, who were afflicted with fiery serpents. Moses instructed them to keep their eyes fixed on the brass serpent—a type of Christ—and they would be healed, but many refused. The way to salvation was too easy, too simple, too straightforward; and those fiery serpents were mighty distracting (see Numbers 21:9; 1 Nephi 17:41; Alma 33:19).

How should leaders deal with the fatal distractions? As Heidi S. Swinton observes, “Joseph understood distractions and did not squander ‘the time . . . to prepare to meet God’ (Alma 34:32).” [21] In carrying out their mission, Joseph and Hyrum Smith had more than their share of distractions to deal with: illness, persecution, forced removals, mob attacks, imprisonment, faithless friends. The setbacks were many and cruel. Any of these distractions might have been fatal to the mission. But by applying a few simple principles, Joseph found ways to transcend the anxieties of the moment and the disruptions to his determined goals.

An Undeviating Course

“Sometimes,” says Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, “we come to Christ too obliquely.” [22] As a boy, Joseph learned to take no indirect paths. He went straight to God for answers to his burning questions. The Book of Mormon taught him, “Behold, the way for man is narrow, but it lieth in a straight course before him, and the keeper of the gate is the Holy One of Israel; and he employeth no servant there; and there is none other way save it be by the gate; for he cannot be deceived, for the Lord God is his name” (2 Nephi 9:41). Joseph followed an undeviating course and led the Saints—those who would follow—along that course.

He had found out early in life that he was not immune to distractions that could be devastating. After his First Vision, he says, “I fell into transgressions and sinned in many things which brought a wound upon my soul.” [23] And later, after losing the Book of Mormon manuscript, he was tortured by his disobedience to God: “All is lost! All is lost! What shall I do? I have sinned. . . . How shall I appear before the Lord? Of what rebuke am I not worthy from the angel of the Most High?” [24]

Then as he matured in his calling, still beset by distractions, he found the strength to stay the course by following one simple rule: “As my life consisted of activity and unyielding exertions, I made this my rule: When the Lord commands, do it.” [25] By staying strictly on the course the Lord marked out for him, Joseph was able to rise above the commotion around him.

Occasionally, Joseph’s eager single-mindedness made him impatient. For example, he could not understand why Church leaders in Missouri could not successfully establish a system of consecrating property and roundly chastised them in letters. His brother Hyrum stepped in and calmed him down, as Bushman pictures it: “One can imagine Hyrum, the wise elder brother, protecting Joseph from his own impulsive nature. Hyrum was reason and sympathy where Joseph was will and energy.” After Hyrum’s intervention, “Joseph toned down his letters and expressed his understanding of the strain of ‘much business.’” [26]

Still, Joseph was wary of the “much business” that kept people from attending to truly important priorities. “Men may preach and practice everything except those things which God commands us to do, and will be damned at last. We may tithe mint and rue, and all manner of herbs, and still not obey the commandments of God.” [27] In other words, we may be very busy doing apparently good things and still deviate from the straight path.

On this point, Elder Oaks admonishes Church leaders to avoid immersing themselves and the Saints in merely good things and to focus on the “best things”: “Just because something is good is not a sufficient reason for doing it. . . . Remember that it is not enough that something is good. Other choices are better, and still others are best. . . . We should be careful not to exhaust our available time on things that are merely good and leave little time for that which is better or best. . . . Stake presidencies and bishoprics need to exercise their authority to weed out the excessive and ineffective busyness that is sometimes required of the members of their stakes or wards.” [28]

Joseph Smith did not allow “excessive and ineffective busyness” to distract him from his calling. In hindsight, we can appreciate the intensity of his focus on the straight and single path that would lead back to the presence of the Lord.

Hyrum Smith also stressed the importance of staying on that undeviating course: “I want to get all the elders together,” he said in the April 1844 conference. “I shall make a proclamation. I want to take the line and ax and hew you, and make you as straight as possible. I will make you straight as a stretched line.” [29]

Magnifying Our Callings

The Lord spoke of Joseph’s kind of focused effort as “magnifying [a] calling,” (D&C 84:33), and Joseph used that expression frequently. [30] He was once asked about it: “‘Brother Joseph, you frequently urge that we magnify our callings. What does this mean?’ He is said to have replied, ‘To magnify a calling is to hold it up in dignity and importance, so that the light of heaven may shine through one’s performance to the gaze of other men. An elder magnifies his calling when he learns what his duties as an elder are and then performs them.’” [31]

For Joseph, to magnify a calling was like viewing it through a microscope. In his time, the term “magnify” would have been associated with a magnifying glass, as Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines the word: “To make great or greater; to increase the apparent dimensions of a body. A convex lens magnifies the bulk of a body to the eye.” [32] A magnifying lens does not scatter light; it focuses light. It brings the rays of the sun to a bright, hard, clear point. Magnifying a calling allows the light of heaven to shine through.

Therefore, we magnify our callings by diminishing the distractions. We focus on what we must achieve and avoid the scattering and dissipating effect of trying to do everything. Elder M. Russell Ballard has said, “Occasionally we find some who become so energetic in their Church service that their lives become unbalanced. They start believing that the programs they administer are more important than the people they serve. They complicate their service with needless frills and embellishments that occupy too much time, cost too much money, and sap too much energy. . . . The instruction to magnify our callings is not a command to embellish and complicate them.” [33]

The challenge for leaders, then, is to avoid the “frills and embellishments” and focus on the hard, simple core of what must be achieved. Elder Ballard said, “The instruction to magnify our callings . . . does not necessarily mean to expand; very often it means to simplify.” [34] And President Boyd K. Packer has warned leaders about the tendency to let “agendas, meetings, and budgets” take up their time at the expense of weightier matters. [35]

Rendering an Account

To stay focused on the cause of Christ, to ward off distractions, Joseph insisted on frequent and regular accountability sessions. “It is required of the Lord, at the hand of every steward, to render an account of his stewardship, both in time and in eternity” (D&C 72:3). A key purpose of these accountability sessions was to refocus the Saints on the revealed priorities.

In his biography of Joseph Smith, Bushman records that “in one particularly intense period between the end of August and the middle of November 1831, twelve conferences were convened in addition to the general Church conference.” [36] In these conferences elders reported their missions, considered new missions, and planned for the temple construction. Joseph met with the elders every week to provide new revelatory direction. High energy and a sense of progress imbued these meetings.

By contrast, too often our leadership meetings in the Church seem perfunctory exercises where goals are not advanced and progress is not tracked. Sometimes no record is kept and no accounting required. Elder Ballard asks, “Are you using the ward and stake councils effectively as they were intended? Don’t let them become meaningless exercises in organizational bureaucracy.” [37]

In one stake, the presidency presented to the members an ambitious goal at the stake conference. This goal was to involve all members of the stake and to be completed within one year. Members were asked to make this goal a priority in their families for the coming year. Weeks and months went by. When semiannual stake conference rolled around again, the goal was barely mentioned. By the end of the year, the goal had been virtually forgotten.

What had gone wrong? The presidency had prayerfully selected the goal and put great emphasis on it. A strategy was designed. The goal was communicated very effectively. But no one in particular was accountable for the goal. No one was called upon to “render an account of his stewardship.” No one tracked progress. Because of the lack of an accountability system, virtually nothing was done.

In the Church, leaders have frequent and regular opportunities to hold accountability sessions—priesthood councils, ward councils, and personal interviews—but we might not be using them as the Lord intended. Of course, the same aimlessness afflicts the business world; goals are announced and directions set, but there is little systematic follow-up. William G. Dyer, former dean of the business school at Brigham Young University, tells this story:

Dr. Wayne Boss, a member of the Church and faculty member at the University of Colorado, was intrigued by the phenomenon he saw in most organizations. A manager would bring his unit together, and they would set goals and attempt to get commitment to high performance; but in just a few months performance almost always slipped. Brother Boss wondered if a Church practice, the Personal Priesthood Interview, would help. He was able in organizations with which he consulted to do research with sixteen work groups. All met to set high goals. Following these meetings, half the managers were asked to hold regular interviews with their people in a process Boss creatively called the PMI—the Personal Management Interview. The other half were left to follow their ordinary follow-up procedures. The evidence was startling. Every group that did not hold the PMI experienced a sharp drop-off in performance. But every group that conducted the PMI continued in the high level of performance—and this level continued for the eighteen months that Boss gathered data. It is a little sad that some of our business organizations, following the process revealed by a prophet, enjoy the blessings of high performance while some of our own wards and stakes do not conduct a regular, good Personal Priesthood Interview and do not realize the benefits. [38]

The accountability process thus makes the key difference in whether or not a goal is executed. When people receive meaningful assignments, when they know they are going to report on their assignments, when they know that someone cares very much if those assignments are carried out, they simply perform better. In the Church, this is particularly true when the assignment clearly supports the great goal of helping people become closer to their Savior.

Joseph and Hyrum Smith spent an immense amount of time meeting in councils and following up on the determinations of councils. The Prophet insisted that Church councils record their decisions, which “will forever remain upon the record, and appear an item of covenant or doctrine.” [39] Commitments made in a Church council thus have the weight of a covenant and should be honored and accounted for.

Joseph provided in the temple a pattern of strict, frequent, and regular accountability for assignments. In the house of the Lord, no one receives an assignment or makes a covenant without the requirement of a formal accounting. The reason for this system is simple: the immense goal of exaltation in the celestial kingdom is simply too big and too ambitious to attain all at once. The Lord divides the goal into manageable tasks and steps suited to our capacity—“here a little and there a little” (2 Nephi 28:30)—but then requires that we report our progress regularly and frequently so he can qualify us for the next step and give us further direction.

For this reason, we take the sacrament not once in a lifetime or twice a year, but every week. President Gordon B. Hinckley said, “I am confident the Savior trusts us, and yet he asks that we renew our covenants with him frequently and before one another by partaking of the sacrament, the emblems of his suffering in our behalf.” [40] This system of frequent and regular accounting prevents us from deviating too far from the straight path to the Savior. It also helps us move forward along that path toward his loving embrace rather than languishing in place.

The principle of regular and frequent accounting applies to any important goal. Most such goals are ambitious and difficult to achieve all at once. Additionally, a new goal requires people to do things they have never done before. Therefore, wise leaders in any organization will regularly call together those who are responsible for the goal and review progress and commit to next steps. Such a meeting is not the customary staff meeting that tends to focus on distracting administrivia—it is totally focused on helping one another achieve the ultimately important goals. “A commandment I give unto you, that ye shall organize yourselves and appoint every man his stewardship; that every man may give an account unto me of the stewardship which is appointed unto him” (D&C 104:11–12).

Conclusion

As Joseph Smith knew in his heart at the grove, the goal of each of us is to return to the glorious presence of our Savior. His leadership was focused on that goal like sunlight through a lens. He gathered thousands of Saints with their eyes fixed on that goal. He built temples to open the way. No distraction could deter him from his single-minded pursuit of that goal. The devoted Hyrum was first in line to make the goal a reality, providing the executive leadership for constructing the temples. By practicing the principle of regular and frequent accounting to the Lord and to each other, the brothers stayed their course and cleared the straight path for us to follow back to our Savior.

These principles apply to any organization. When every person clearly knows the goal, knows his or her part in achieving the goals, and accounts regularly and frequently for progress, only then do we make progress. We avoid the costly and painful deviations that put that which matters most at the mercy of that which matters least. President N. Eldon Tanner said, “Those who keep on the straight and narrow path leading to their goal, realizing that the straight line is the shortest distance between two points and that detours are very dangerous, are those who succeed in life and enjoy self-realization and achievement.” [41] It is not easy, however, to stay on that straight course unless we practice the principles of focus and accountability that Joseph practiced. To counteract the centrifugal force of the daily whirlwind that threatens to blow us off course—that is our challenge.

Too many Church leadership meetings have little to do with helping people come to the Savior. Too many Gospel Doctrine classes fail to focus on the Atonement of the Savior. Too many priesthood interviews and home visits fail to challenge people to turn to the Savior. Too many parents allow the distractions of good things to overwhelm the family’s focus on the best thing—the exaltation of the family in the Savior’s kingdom.

President Thomas S. Monson sums it up this way: “Our goal is the celestial kingdom of God. Our purpose is to steer an undeviating course in that direction.” [42] Joseph and Hyrum Smith are the great examples of persistence in following that course and refusing to deviate; let us stay on course with them as we lead others to achieving the greatest of goals.

Notes

[1] The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, comp. and ed. Dean C. Jessee, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 12.

[2] Chris Zook and James Allen, Profit from the Core (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002), 11.

[3] Zook and Allen, Profit from the Core, 2.

[4] Ram Charan and Geoffrey Colvin, “Why CEOs Fail,” Fortune, June 21, 1999, 69.

[5] Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan, Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done (New York: Crown Business, 2002), 38.

[6] “The Execution Quotient: The Measure of What Matters,” 8, http://

[7] Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 451.

[8] Dallin H. Oaks, “Focus and Priorities,” Ensign, May 2001, 82.

[9] Robert B. Flanders, “Dream and Nightmare: Nauvoo Revisited,” The Restoration Movement: Essays in Mormon History, F. Mark Mckiernan and others, eds. (Lawrence, KS: Coronado Press, 1973), 156, quoted in Ronald K. Esplin, “Significance of Nauvoo for Latter-day Saints,” Journal of Mormon History 16 (1990), 78.

[10] Esplin, “Significance of Nauvoo,” 78, 72.

[11] Quentin L. Cook, “Rejoice!” Ensign, November 1996, 28.

[12] Dallin H. Oaks, “Our Strengths Can Become Our Downfall,” BYU fireside address, June 7, 1992, http://

[13] Thomas S. Monson, “True to the Faith,” Ensign, May 2006, 21.

[14] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1932–51), 6:230.

[15] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 218.

[16] Smith, History of the Church, 5:423–25.

[17] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 220.

[18] Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith: A Life of Integrity (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 86.

[19] Smith, History of the Church, 1:349–50.

[20] Andrew J. Jenson, “The Nauvoo Temple,” Historical Record 8 (June 1899), 865–66.

[21] Heidi S. Swinton, “Joseph Smith: Lover of the Cause of Christ,” BYU devotional address, November 2, 2004, http://

[22] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Come unto Me,” BYU fireside address, March 2, 1997, http://

[23] Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, 12.

[24] Lucy Mack Smith, Lucy’s Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir, ed. Lavina Fielding Anderson (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2001), 418–19.

[25] Smith, History of the Church, 2:170; emphasis in original.

[26] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 219.

[27] Smith, History of the Church, 6:223.

[28] Dallin H. Oaks, “Good, Better, Best,” Ensign, November 2007, 104–7.

[29] Smith, History of the Church, 6:298.

[30] See, for example, D&C 24:3, 9; 66:11; 84:33; 88:80; Smith, History of the Church, 4:603, 606.

[31] Thomas S. Monson, “All That the Father Has,” Ensign, July 1989, 68.

[32] Noah Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language, 1828, s.v. “magnify.”

[33] M. Russell Ballard, “O Be Wise,” Ensign, November 2006, 19.

[34] Ballard, “O Be Wise,” 19.

[35] Boyd K. Packer, “Principles,” Ensign, March 1985, 6.

[36] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 251–52.

[37] M. Russell Ballard, “Members Are the Key,” Ensign, September 2000, 8.

[38] William G. Dyer, “Dedication of the N. Eldon Tanner Building,” April 5, 1983, http://

[39] Kirtland High Council Minutes, January 18, 1835, cited in Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 257.

[40] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Trust and Accountability,” BYU devotional address, October 13, 1992, http://

[41] N. Eldon Tanner, “Success Is Gauged by Self-Mastery,” Ensign, May 1975, 4.

[42] Monson, “True to the Faith,” 21.