“They Were of One Heart and One Mind"

Councils in Zion, Zion in Councils

Mark E. Mendenhall and J. Bonner Ritchie

Mark E. Mendenhall and J. Bonner Ritchie, “‘They Were of One Heart and One Mind’: Councils in Zion, Zion in Councils,” in Joseph and Hyrum—Leading as One, ed. Mark E. Mendenhall, Hal B Gregersen, Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Heidi S. Swinton, and Breck England (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 1–20.

The Prophet Joseph Smith held up Zion to the Latter-day Saints as a perfected and celestial organization marked by the unity of its members. We each covenant to build up Zion, that individual and communal condition where everyone is of “one heart and one mind” (Moses 7:18), but often we are unsure how to go about it. How do we as individuals, who differ so much in our opinions, temperaments, and backgrounds, arrive at that kind of unity?

If Zion means to be of “one heart and one mind” with others, then there must be a process for achieving it. That revealed process is the council system. [1] When we understand how to use councils as the Lord does, and when we conform our souls to the principles necessary to properly counsel together, we will find the joy of Zion we so desperately seek. But even though prophets have taught and still teach the eternal principles of councils to us, we seem to miss their message. Maybe we fall short because we lack experience with effective councils. Maybe we are listening less to the prophets than to our own ideas—for, unknowingly, we may often drag principles we have learned from society, business, family background, or the education system into our families and our Church callings. Until we learn how to counsel together in the Lord’s kind of council, we will not reach the Zion we ache for in our hearts.

The council system was not only revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith, but it was restored through him. As early as 1831, the Prophet was actively using committees to govern the Church; by 1834 he was teaching Church leaders the principles of governing by council that he had learned through revelation. [2] As he was taught line upon line, precept upon precept how the Church should be organized (e.g., with quorums, bishoprics, the Relief Society), he also taught that every unit of the Church should be governed according to the council system. [3]

The First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles govern themselves according to the principles of the council system, [4] and they have desired that the council system be learned and applied at all levels of Church administration—especially within the family. [5] However, as a people, the Latter-day Saints do not always fully understand and apply the principles of the council system. [6]

A council in the kingdom of God is both an organizational unit and a way to manage that unit. [7] Councils are not merely meetings where calendars are coordinated and assignments are distributed. Councils are organized so we can learn and apply the principles of love and service; so we can plan, analyze problems, and make decisions to move forward the kingdom of God. [8] In short, councils are the means by which we experience the joy of Zion.

This chapter reviews the principles and processes of councils as taught by the Prophet Joseph and succeeding prophets and apostles, and it shows how Joseph and Hyrum applied these principles. Born into a family that counseled together frequently, Joseph and Hyrum were no doubt prepared to understand the importance of the council system to the building up of the kingdom of God. The Smith family often held family councils. For example, in 1816, after three years of crop failures, they met as a family to consider relocating to New York: “We all now sat down and maturely counseled together as to what course it was best to take, and how we should proceed to business in our then destitute circumstances. It was agreed by each one of us that it was most advisable to apply all our energies together and endeavor to obtain a piece of land, as this was then a new country and land was low, being in its rude state.” [9]

As this Smith family council illustrates, councils are not complicated. In fact, we might be turned off by the simplicity of this solution to the problem of Zion. We should remember the warnings of holy writ not to discount powerful principles because they seem to us naive or simplistic: “Now ye may suppose that this is foolishness in me; but behold I say unto you, that by small and simple things are great things brought to pass; and small means in many instances doth confound the wise. And the Lord God doth work by means to bring about his great and eternal purposes; and by very small means the Lord doth confound the wise and bringeth about the salvation of many souls” (Alma 37:6–7).

Councils are not necessarily large numbers of people. A council exists where at least two people are trying to determine what the Lord would have them do—thus, a married couple is a council, a parent-child relationship is a council, and a personal priesthood interview is a council. [10] Joseph and Hyrum not only led and participated in formal Church councils, but they also applied revealed principles of councils to their personal relationship as brothers. The spirit of the council system can and should influence all communication between spouses, parents and children, friends, or members of presidencies.

The Principles and Process of Councils

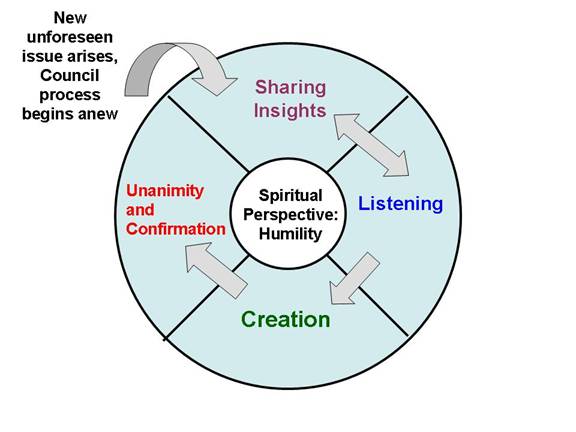

People define the elements of the council system in different ways, but in this discussion we propose a council “process” of five steps or phases. [11] Each step is based on an organizational principle. The degree to which we obey each principle is the degree to which the Lord will bless the council with his Spirit. The principles of spiritual perspective, sharing insights, listening, creation, and confirmation and unity can create in the councils of Zion the joy of Zion.

These principles are illustrated in figure 1. The process of counseling together begins with the core principle, humility, and then from the top of the diagram, beginning with the principle of sharing insights, moves clockwise.

Figure 1: The Council Process

Principle 1: Spiritual Perspective

Councils do not begin when a family council convenes or when the members of a ward council bow their heads in an opening prayer. A council operates according to the Lord’s will depending on the spiritual perspective or attitude the council members bring with them. This spiritual perspective is the glue that holds the process together; without it, the other principles would be applied inappropriately and could not produce the desired outcomes of councils: namely, revelation, unity, love, vision, Zion.

We are all different by spiritual nature and mortal experience—we see and make sense of the world around us, and even the gospel, somewhat differently from each other. Each of us has spiritual and temporal strengths; there are some things we just seem to know instinctively. The dangerous trap we are all prone to fall into, however, is to assume that because we are gifted in some areas of life, our views regarding all other areas of life are valid and correct as well. To participate effectively in councils, we must realize that our individual understandings, views, and judgments are limited, and follow the admonition of the Lord: “The decisions of these quorums . . . are to be made in all righteousness, in holiness, and lowliness of heart, meekness and long suffering, and in faith, and virtue, and knowledge, temperance, patience, godliness, brotherly kindness and charity” (D&C 107:30).

Thus, we must enter a council with a humble spiritual perspective. As it applies to councils, humility means understanding that your own view of any situation, issue, or circumstance is incomplete. My view of what the young women of my ward need in order to progress will likely be different from yours. None of us sees the complete picture, yet we often assume that we do. Thus, we often spend our energy in meetings trying to convert other people to our point of view rather than listening to everyone’s opinions and ideas to gain a better sense of what the true picture is. [12]

Joseph Smith illustrated this kind of humility when he ordained Harvey Whitlock a high priest in 1831. Immediately after he was ordained, Brother Whitlock’s appearance changed, and he was not able to speak. Levi Hancock recorded what occurred next: “Hyrum Smith said, ‘Joseph, that is not of God.’ Joseph said, ‘Do not speak against this.’ ‘I will not believe,’ said Hyrum, ‘unless you inquire of God and he owns it.’ Joseph bowed his head and in a short time got up and commanded Satan to leave Harvey, laying his hands upon his head at the same time.” [13]

Joseph could have spurned this input from Hyrum or even seen it as an attack on his legitimacy as a prophet. Instead, Joseph reconsidered and then prayed about it. It turned out that Hyrum’s view was correct, and Joseph took the appropriate action. Humility is the deep realization that it is very difficult to see the big picture and that we are fooling ourselves when we think we do. President George Q. Cannon described how Latter-day Saints should approach a council with humility:

If I were going to a priesthood meeting, where there were important matters to attend to, it is my duty, as a servant of God, to go to that meeting with my mind entirely free from all bias. I have my views; but I should not be set in my views; I should not be wedded to them. I should enter that assembly with my mind entirely free from all influence that would prevent the operation of the Spirit of God upon me. . . . If I were to go, and all the rest were to go, with this spirit, then the Spirit of God would be felt in our midst, and that which we would decide upon would be the mind and will of God. [14]

When we counsel with our spouse or our children or enter a more formal council with our minds already made up, with an unalterably fixed attitude, we kill the potential for unity and abort Zion. When we accept that a variety of perspectives brings strength rather than weakness to a council, we can solve problems effectively and unitedly. President Joseph F. Smith taught:

With [people] of varying intelligence, judgment and temperament, of course it follows that in the consideration of a given matter there will be a variety of views entertained, and discussion of the subject will nearly always develop a variety of opinions. All this, by the way, is not detrimental to the quality of any purposed action, since the greater the variety in temperament and training, of those in conference, the more varied will be the view-points from which the subject in question is considered, until it is likely to be presented in almost every conceivable light, and its strength as well as its weakness developed, resulting in the best possible judgment being formed of it. [15]

As we let the insights of our spouses, children, and ward members illuminate the issue at hand, we will be amazed to see a complex whole rather than just bits and pieces. We build the kingdom effectively only when we work from an accurate and complete understanding of the challenges and opportunities before us, and such understanding comes only through counseling together in humility.

Principle 2: Sharing Insights

Sharing views is the beginning of the council process [16] (see fig. 1). Members of councils have a sacred responsibility to share their ideas, concerns, insights, and experiences with the council. In fact, the Prophet Joseph placed early Church leaders under covenant to share their thoughts and concerns in councils [17] and to do so with wisdom and with respect. After a particular council meeting in 1836, some of the members observed that the process had been a rocky one and that “many who had deliberated . . . were darkened in their minds.” [18] The Prophet then taught them more about the council process:

Each should speak in his turn and in his place, and in his time and season, that there may be perfect order in all things; and that every man, before he makes an objection to any item that is brought before a council for consideration, should be sure that he can throw light upon the subject rather than spread darkness, and that his objection be founded in righteousness, which may be done by men applying themselves closely to study the mind and will of the Lord, whose Spirit always makes manifest and demonstrates the truth to the understanding of all who are in possession of the Spirit. [19]

Ideally, before convening a council, the leader should notify council members of the topic to consider so they have time to ponder, pray, and crystallize their thoughts about the topic. When council members know the topic in advance, they can come to the council better prepared to share the thoughts of their hearts. The leader of the council should ask each individual, in turn, to share his or her view of the issue. While sharing these thoughts, no council member should be interrupted until finished. [20] Then, if any in the council wants the speaker to clarify, he or she may request it. When all members can share the thoughts of their hearts, we learn things about the issue that by ourselves we would never consider. Sharing helps us to see collectively a more accurate big picture, a similar understanding that is itself a form of unity.

If a council member does not share his or her views, the group sees only a partial picture and then arrives at inadequate solutions based on incomplete understanding. We cannot hope to combine our differing perspectives into a mutual understanding unless we know what they are. Suppression of ideas, thoughts, and concerns ensures that problems do not get adequately solved. Also, when people suppress their ideas and do not share them, it is difficult for the group to be completely unified in their course of action. [21]

Of course, council members will not share their thoughts if they have reason to believe that other council members will mock them, discount them, or ignore them. Mutual trust is essential to effective councils, and trust is built through listening. [22]

Principle 3: Listening

We must learn to listen to understand, not to shape arguments in our minds to present when it is our turn to speak. As figure 1 indicates, listening is the second phase of the council process; but in truth, as the two-headed arrow linking Sharing Insights and Listening illustrates, sharing and listening take place simultaneously when we counsel together.

In 1838, the Saints were planning to move from Kirtland, Ohio, to Far West, Missouri. The Prophet Joseph and Sidney Rigdon had already left. Hyrum Smith, the only member of the First Presidency still in Kirtland, met with the Seventy in the Kirtland Temple to plan the move. Evidently, in one of these meetings, Hyrum proposed chartering a steamboat to transport Saints to Missouri. In a later meeting, the council discussed Hyrum’s proposal and decided on another means of transport. [23] Hyrum sustained the decision and said, “The Saints had to act oftentimes upon their own responsibility without any reference to the testimony of the Spirit of God in relation to temporal affairs . . . [and] that he had so acted in this matter and ha[d] never had any testimony from God that the plan of going by water was approved by Him, and that the failure of the scheme was evidence in his mind that God did not approve of it.” [24]

Hyrum listened not only with his ears but also with his heart during that council meeting. As he did so, he discerned that his approach would be inadequate to the need. Instead of vigorously defending his stance or asserting his authority as the only member of the First Presidency on the scene, he realized that his plan was not sustained to be a witness of God’s will. As we listen humbly as Hyrum did, we will naturally reorient our own views to the larger perspective we gain from the views of others. Through sharing and listening in councils, all council members can expand their views. When they arrive at an expanded view of a problem, the solution they then create is more effective. Elder M. Russell Ballard teaches that councils should “promote free and open expression. Such expression is essential if we are to achieve the purpose of councils. Leaders and parents should establish a climate that is conducive to openness, where every person is important and every opinion valued. The Lord admonished: ‘Let one speak at a time and let all listen unto his sayings, that when all have spoken that all may be edified’ (D&C 88:122). Leaders should . . . remember that councils are for leaders to listen at least as much as they speak.” [25]

We tend not to listen when we believe that we have all the answers or that our wisdom should govern. President George Q. Cannon counsels us to avoid this attitude:

I say to you, as Elders and Latter-day Saints, that . . . [it] is not right for us, before going into council, to commit ourselves to any line of action, nor to any decision. It is just such things as these that frequently lead to division and to strife in the Church of Christ—men determined beforehand that they are going to have their way, regardless of others. “I am going to have my will; I am going to carry my point; I am going to have what I think to be right, regardless of the will of others or of the will of God.” Beware of such a spirit! It will lead to evil, to division, to strife, and to the withholding of the mind and will of God from us. [26]

A Picture of a Council

Let’s draw a picture of a council that follows these steps of the council process. A Relief Society president sees that some converts are struggling to integrate into the ward and suggests to the bishop discussing the issue in ward council. The bishop agrees and asks council members to prepare to discuss “how the ward can better retain our converts” in a meeting the following week.

During the week, the council members think about their personal experience with new converts and study auxiliary and quorum policies and programs for helping new converts. They read scriptures and conference talks about the needs of converts. They may discuss the issue with family and friends to gain their insights as well. In their personal prayers, they petition Heavenly Father to bless the proceedings of the upcoming council. As the ward council meeting approaches, they crystallize their thoughts and ideas, knowing that they will be called upon to share their views with the council. They prepare what to say to be concise and clear.

They also review in their minds and hearts the spirit they must take to the council. They check their own excitement about the advice they want to give, reminding themselves that they might not understand the whole issue and that their plans and recommendations might be off target. In short, they remind themselves to be humble. They remind themselves that they should not desire what they want but what the Lord wants. They remind themselves that they love the other council members and promise themselves that they will speak the truth in love and will try their best not to step on others’ feelings or mock their ideas. They remind themselves of their covenants and that they are bound together as a council to carry out the Lord’s work.

With this spirit, the council members come to the meeting. It is opened with prayer, and the bishop convenes the council. He very briefly reminds the council members of the principles of councils and introduces the topic of discussion. He then asks that members of the council share their views on the matter. The Relief Society president shares her concerns and possible directions. Everyone listens intently to her without interrupting her. Next, the elders quorum president speaks, and so on, until all have shared their views. During this process, the council listens intently to understand the issue from all sides. As sharing progresses, the members come to see the full picture of convert needs. If council members have progressed to this point, they can then take the next step in the council process.

Principle 4: Creation

Once they fully understand the issue, the council then naturally creates solutions and makes decisions. In this phase we offer ideas, listen to ideas, and work at sensing the contribution of the Holy Ghost. Creating solutions is not a lockstep process; rather, it comes from further sharing and listening to each other and to the Spirit. In a poignant moment just before the Martyrdom in June 1844, Joseph and Hyrum Smith counseled together to make a fateful decision. Joseph had left Nauvoo to avoid arrest and mob action, but some of the Saints viewed his behavior as an act of cowardice. He selflessly responded, “If my life is of no value to my friends it is of none to myself.” Joseph turned, as he had done so many times before, and asked his older brother for counsel. “Brother Hyrum,” he said, “you are the oldest, what shall we do?” Hyrum responded, “Let us go back and give ourselves up, and see the thing out.” Joseph pondered the proposal for a few moments and said, “If you go back I will go with you, but we shall be butchered.” Hyrum replied, “Let us go back and put our trust in God. . . . The Lord is in it. If we live or have to die, we will be reconciled to our fate.” [27] President John Taylor later wrote that it was necessary that Joseph and Hyrum seal their testimonies with their blood (see D&C 135:1–3). They made the decision to return to Nauvoo to expose themselves to death as they counseled together and sensed the will of the Spirit.

Effective solutions emerge through discussion enhanced by the whisperings of the Holy Ghost to the individual hearts of the council members. The Holy Ghost helps us see what we have never seen, helps us change our opinions, and helps us love each other. But the Holy Ghost can participate in a council only if the members are trying to abide by the principles of effective councils.

A solution may come fairly quickly, or it may take more than one council meeting. When the solution does emerge, or if the final decision comes by revelation to the bishop after a thorough discussion, it should be the unified decision of all council members as directed by the Holy Ghost. Elder Rulon G. Craven, former secretary to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, often observed this process among the Twelve in council:

They speak their mind. However, they are also good listeners and speak when moved upon by the Holy Spirit. Their posture in quorum meetings is to listen and sense the directing power of the Spirit, which always leads to a unity of decision. I marveled as I watched the directing power of the Spirit touch the minds and hearts of the members of the Twelve, influencing the decision-making process. . . . They strive continually to abide by the counsel of the Lord found in section 107, verse 30, of the Doctrine and Covenants. [28]

A council is a process for obtaining the Lord’s will. We work to create a solution, and the Lord sends the Holy Ghost to influence the process so that the product that we create is in harmony with his will. We receive confirmation from the Spirit and go forward in unity.

Principle 5: Confirmation and Unity

The Holy Ghost does not encroach on our agency when he assists the discussion of a council; rather, he enhances our ability to trust each other, to listen to other viewpoints without prejudice, to speak the thoughts of our hearts and minds with humility, to perceive the emergent course of action without bias, to appreciate the gifts of our fellow council members, and to bend our desires to the greater good and to the Lord’s will. In short, the Holy Ghost comes to councils to act as a partner in our strivings and works with us to create a beautiful course of action in harmony with the mind of the Lord.

As the Holy Ghost enters our discussions, the emergent solution resonates in the hearts and minds of the council members. There is a sweet bond of unity of intellect and emotion. We feel Zion. We taste of oneness. Our unity produces motivation, excitement, hope, faith, zeal, energy, focus, and exhilaration in the work of the Lord.

Continuing, consistent counseling together according to the principles of the council system produces in our relationships a David-Jonathan bond of unity and love. John Taylor’s brother William observed this kind of bond whenever Joseph and Hyrum met. He wrote,

Never in all my life have I seen anything more beautiful than the striking example of brotherly love and devotion felt for each other [as was demonstrated] by Joseph and Hyrum. . . . I witnessed this many, many times. No matter how often, or when or where they met, it was always with the same expression of supreme joy. It could not have been otherwise, when both were filled to overflowing with the gift and power of the Holy Ghost! . . . It was kindred spirits meeting! [29]

Unity is not a hasty, unconsidered agreement by everyone in a council regarding a course of action—that is compliance, not unity. Unity is the mutual acceptance of a course of action that has emerged after respectful discussion within a council. At times, the solution will naturally manifest itself to all the council members, and the leader has only to put it into words. At other times, after adequate discussion, the leader who holds keys will petition Heavenly Father and receive revelation about the course to follow. In either case, the Lord reveals his will through the council system.

Illustration from a Family Council

Mark, one of the authors of this chapter, tells this story:

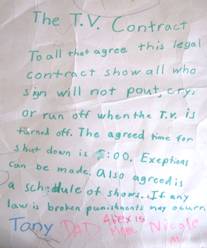

In 1996, my wife, Janet, and I felt that our four children were watching too much television. When we asked them to limit the cartoons and other programs they liked to watch, they would get cranky, cry, or misbehave. After our authoritarian mandates failed, I wondered, “Is it possible that councils would work with young children?” We tried to follow the principles about preparing for the council. We shared with the children ahead of time what a council was, that it was important that each of them share their views about the situation, and that they should listen to each other without interrupting or judging others. The goal was to come up with a decision we all felt good about.

The council convened at the kitchen table. Our oldest son was twelve, our two daughters were nine and five, and our youngest son was one. It took a while for the children to buy into this process, but when they sensed that my wife and I were serious in our desire to make this a family decision, they began to participate and share their ideas and concerns. I listed on a large sheet of paper the different ideas they proposed to deal with the problem. During this stage we made sure that no one judged or criticized anyone’s ideas. After the paper was filled with ideas, we began to discuss them. Comments, concerns, analysis of the ideas—all was done with respect, and the children brought up issues that my wife and I had never thought of. I was amazed!

Nevertheless, we reached a roadblock. None of our ideas quite solved the problem to everyone’s satisfaction. The sticking point: no one believed we would actually live by our commitment to turn off the TV at a certain time (although this did not seem to be a problem to me). The children were afraid they would turn on the television accidentally or in a moment of weakness. A true impasse had been reached—with my wife and me firmly biting our tongues. We were inclined to make a rule and enforce it, but we knew that if we did that, we would destroy the council process.

As our family sat around the kitchen table, stumped and trying to figure out where to go next, our second-oldest daughter was doodling on a piece of paper. Without looking up, she said in one long breath, “Well, we could make a sign that says, ‘The TV is now off!’ and we could hook it onto the back of the TV and when it was time for the TV to go off, Mom or Dad could just put the sign over top of the TV screen so we could all see the sign and know that we shouldn’t watch the TV.”

The rest of the family sat stunned. Our oldest son looked at his sister in amazement, and then said, “You know, that would work!” My wife found a poster board, and on it we simply wrote, “TV Off.” Then one of the children enthusiastically suggested, “Let’s decorate the sign!” Out came the pastel magic markers. My oldest son suggested that to be serious about this, we should draw up a family contract on the back and everyone should sign it. Though the wording of the contract was not exactly what the Prophet Joseph had in mind when he taught that council members should be bound by covenant to each other, somehow I think he would have approved of our “television constitution” (see below).

Front of television sign

Back of television sign

In preparing this chapter, I asked my oldest daughter, who is now twenty and home between semesters from Brigham Young University–Idaho, if she remembered the night we made the television sign. To my surprise, she described the evening in great detail. When I found the sign, she clearly remembered which part she had drawn and decorated. She said, “I remember it was just so cool because we came up with the plan as a family—we did it all together.”

Council Renewals

Because our family created this solution together, we were united in our belief in it. We reduced our television viewing time without contention. Still, we needed additional councils to adjust to new circumstances. Our television sign and plan did not last forever. It was effective for some time, but our four-year-old son liked to play with the sign; he would tug on it and accidentally (or maybe purposely) pull it off of the television set. We would replace the sign and within a day or two find it lying on the floor again. Sadly, we came to realize that it would be impossible to continue to use the sign.

New issues always arise in any marriage, family, or ward, so councils must continue their work. The process of creating unity anew, over and over again, is essential to building Zion in our families and our wards. Zion expands when people with diverse gifts, talents, views, and experiences combine their souls in councils. Councils that act in obedience to correct principles help the kingdom grow in ways that are welded to the will of God.

Councils are a way of life after the order of the celestial kingdom. The gods organize and create through councils, and part of our preparation for exaltation is to learn this way of life in mortality. [30] The principles that govern councils give birth to Zion among us now and forever.

Notes

[1] This process is taught in M. Russell Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils: Learning to Minister Together in the Church and in the Family (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997).

[2] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 1:219; 2:25–26. See also Joseph F. McConkie and Craig J. Ostler, Revelations of the Restoration: A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants and Other Modern Revelations (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 743; Doctrine and Covenants 107:29; Kirtland Council Minute Book, February 17, 1834 (The Book of Abraham Project, http://

[3] Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 251–53.

[4] See Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 37–50; see also Boyd K. Packer, “I Say Unto You, Be One,” Brigham Young University devotional address, February 12, 1991, 3–4.

[5] See Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 147–60. See also David O. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1937, 121–22.

[6] Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 17, 57, 71–75, 85–86, 94–95, 127.

[7] J. Bonner Ritchie, “Priesthood Councils,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1141.

[8] Ritchie, “Priesthood Councils,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1141.

[9] Lucy Mack Smith, The Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 86; emphasis added.

[10] Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 127.

[11] The principles we use as a summary framework are derived most directly from Mark E. Mendenhall and W. Jeffrey Marsh, “On Integration: The Resurgence of Mary P. Follett and the Uncelebrated Contribution of Joseph Smith,” Proceedings, Academy of Management, Atlanta, Georgia, August 2006; Mark E. Mendenhall and W. Jeffrey Marsh, “Toward a Model of Collaborative Leadership Learning: Mary P. Follett and Joseph Smith Revisited,” paper presented at the Academy of Management, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, August 6, 2007.

[12] Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 1–20.

[13] Levi Ward Hancock, autobiography, circa 1854, 90–92, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, quoted in Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith: A Life of Integrity (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 44.

[14] George Q. Cannon, “Seeking the Pure Love of Christ,” in Collected Discourses Delivered by President Wilford Woodruff, His Two Counselors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, comp. and ed. Brian Stuy, (Woodland Hills, UT: B. H. S. Publishing, 1988), 2: 90–91.

[15] Joseph F. Smith, “Editor’s Table,” Improvement Era, January 1905, 211–212.

[16] See Ballard, Counseling with our Councils, 161–70.

[17] Andrew F. Ehat, “‘It Seems Like Heaven Began on Earth’: Joseph Smith and the Constitution of the Kingdom of God,” BYU Studies 20, no. 3 (1980): 260.

[18] Smith, History of the Church, 2:370.

[19] Smith, History of the Church, 2:370.

[20] See Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 113–16.

[21] See Mary P. Follett, “Constructive Conflict,” paper presented at the Bureau of Personnel Administration, 1925, 9; reprinted in Pauline Graham, ed., Mary Parker Follett: Prophet of Management (Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press, 1995), 67–95.

[22] See J. Bonner Ritchie, “Taking Sweet Counsel,” BYU 1990–91 Devotional and Fireside Speeches (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1991), 133–40.

[23] O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 166.

[24] Smith, History of the Church, 3:94.

[25] M. Russell Ballard, “Strength in Counsel,” Ensign, November 1993, 76.

[26] Cannon, “Seeking the Pure Love of Christ,” 91.

[27] Smith, History of the Church, 6:549–50.

[28] Rulon G. Craven, Called to the Work (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1985), 111–12.

[29] William Taylor, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet,” Young Women’s Journal, December 1906, 547–48, quoted in O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 272.

[30] See Ballard, Counseling with Our Councils, 21–36.