"Let Him Ask of God"

Joseph’s and Hyrum’s Definining Questions

Hal B. Gregersen and Mark E. Mendenhall

Hal B Gregersen and Mark E. Mendenhall, “'Let Him Ask of God': Joseph’s and Hyrum’s Defining Questions,” in Joseph and Hyrum—Leading as One, ed. Mark E. Mendenhall, Hal B Gregersen, Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Heidi S. Swinton, and Breck England (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 185–204.

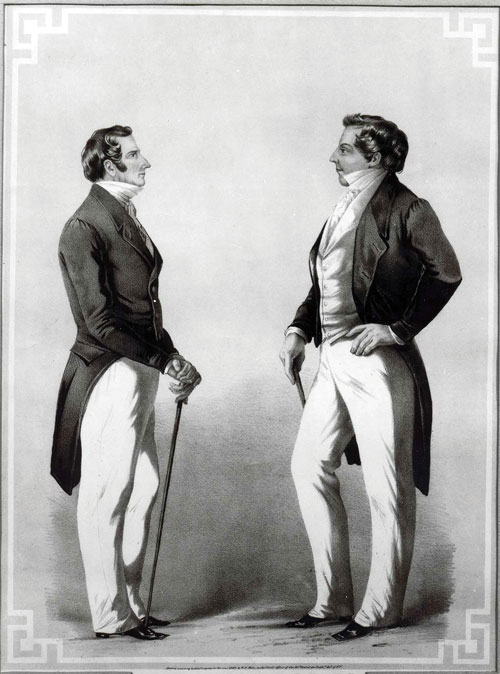

Joseph and his brother Hyrum were not idle observers of the political landscape. They both held a number of offices of public trust. The prophet Joseph Smith offered the wold great principles in relation to effective leadership in government, politics, and the public square. The beliefs he espoused can help secure freedom and liberty for all people. (The Two Martyrs, Joseph & Hyrum Smith; Library of Congress: lithograph by Sarny & Major, 1847.)

Joseph and his brother Hyrum were not idle observers of the political landscape. They both held a number of offices of public trust. The prophet Joseph Smith offered the wold great principles in relation to effective leadership in government, politics, and the public square. The beliefs he espoused can help secure freedom and liberty for all people. (The Two Martyrs, Joseph & Hyrum Smith; Library of Congress: lithograph by Sarny & Major, 1847.)

The dispensation of the fulness of times was ushered in with a sincere, soul-searching question. Confronted with diverse religious preachers and equally diverse doctrine, young Joseph began to form what may well be the most critical inquiry of the latter days. He reflected: “What is to be done? Who of all these parties are right; or are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?” (Joseph Smith—History 1:10). Such questions weighed so heavily on his mind that a single Bible verse struck “with great force into every feeling of [Joseph’s] heart” (Joseph Smith—History 1:12). This scripture delivered a potent, simple directive: “If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God” (James 1:5).

Joseph reflected on this passage repeatedly, letting it sink deeply into his fourteen-year-old heart. Eventually Joseph concluded that he “must either remain in darkness and confusion” or “do as James directs, that is, ask of God” (Joseph Smith—History 1:13). With a determination to ask, Joseph entered the Sacred Grove with honest questions and in search of honest answers. On perfect cue, the adversary felt sorely threatened by Joseph’s authentic inquiry and invaded the sacred space of this prayer, blanketing the attempt with “thick darkness” (Joseph Smith—History 1:15).

Clearly, Satan knows the power of questions. Sincere, authentic questions are not the casual, garden-variety questions that we daily ask others and ourselves. Nor are they based on idle curiosity or intellectual yearnings, but they are “whole-souled” in nature. They reflect a deep yearning to know God’s will. They manifest the need for knowledge that aligns our will, without reserve, to the will of God. Such questions help us approach the state of heart and soul from which the Savior uttered: “Not my will, but thine, be done” (Luke 22:42).

In contrast, our questions to God, ourselves, and others will not be authentic if we “ask amiss” (James 4:3). Nephi understood that God “will give liberally” if we ask not amiss (2 Nephi 4:35), that is, if we approach him whole-souled and aligned to his will and without self-centered desires, idle curiosity, or half-hearted yearnings. Heavenly Father can answer authentic questions fully because they are asked “in the Spirit . . . according to the will of God” (D&C 46:30); as a result, Father promises that it will be “done even as he asketh” (D&C 46:30). Only authentic questions can prepare the petitioner’s soul to absorb the potential enormity of God’s forthcoming answer.

The adversary’s extraordinary efforts to prevent Joseph’s authentic question from being brought before God failed, however. In response to ominous doom and destruction driven by the adversary’s “marvelous power” (Joseph Smith—History 1:16), Joseph exerted all of his earthly energy to penetrate the heavens. Light then burst forth from the Father and the Son. In the presence of such blinding light—which came immediately after a direct encounter with absolute darkness—Joseph still clung to his question. His deep desire for wisdom demanded the asking.

He wrote: “My object in going to inquire of the Lord was to know which of all the sects was right. . . . No sooner, therefore, did I get possession of myself, so as to be able to speak, than I asked the Personages who stood above me in the light, which of all the sects was right” (Joseph Smith—History 1:18).

The fact that Joseph had the ability to courageously ask his question in the presence of God testifies of Joseph’s greatness, which was made clear to B. H. Roberts through an experience he had during his mission in Iowa. One morning B. H. Roberts awoke and was astonished to see an angel standing next to his bed. After a few moments, the shock of the event passed and was replaced with “a beautiful feeling of confidence and pleasure.” Before the messenger departed, he “bent forward smiling and slowly and gracefully raising his hand he pointed to the eastward and said in a voice, the tenderness and beauty of which can never be forgotten, ‘You are called to go to Rockford.’” [1]

B. H. Roberts had wanted to respond the angelic messenger, but Roberts’s biographer, Truman G. Madsen, observed that Roberts “later marveled that he did not have the presence of mind to speak, to inquire, or even to reply. This wonderment is perhaps reflected in his comment about the manifestations of the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith in the Sacred Grove. ‘It gives evidence of the intellectual tenacity of Joseph Smith that in the midst of all these bewildering occurrences he held clearly in his mind the purpose for which he had come to the secluded spot.’” [2]

Undoubtedly, Joseph’s unwavering determination to follow James’s counsel and “ask of God” sustained the Prophet’s constant quest for further light and knowledge. [3] Joseph’s and Hyrum’s honest questions provoked equally honest answers from God, reminding us that God is neither a respecter of persons nor afraid to answer the most perplexing pleas for answers.

Hyrum’s Authentic Questioning

Like Joseph, Hyrum was wont to ask authentic questions, not just of God, as we will see shortly, but also of the Saints. For example, his crystal-clear discourse on the Word of Wisdom was peppered heartily with questions to help others grasp and live the doctrine:

The Lord has told us what is good for us to eat, and to drink, and what is pernicious; but some of our wise philosophers, and some of our elders too, pay no regard to it; they think it too little, too foolish, for wise men to regard—fools! where is their wisdom, philosophy and intelligence? from whence did they obtain their superior light? Their capacity, and their power of reasoning was given them by the great Jehovah: if they have any wisdom they obtained it from him: and have they grown so much wiser than God that they are going to instruct him in the path of duty, and to tell him what is wise, and what is foolish. They think it too small for him to condesend to tell men what will be nutritious or what will be unhealthy. Who made the corn, the wheat, the rye, and all the vegetable substances? and who was it that organized man, and constituted him as he is found? who made his stomach, and his digestive organs, and prepared proper nutriment for his system, that the juices of his body might be supplied; and his form be invigorated by that kind of food which the laws of nature, and the laws of God has said would be good for man? . . . We are told by some that circumstances alter the revelations of God—tell me what circumstances would alter the ten commandments? they were given by revelation—given as a law to the children of Israel;—who has a right to alter that law? Some think that they are too small for us to notice, they are not too small for God to notice, and have we got so high, so bloated out, that we cannot condescend to notice things that God has ordained for our benefit? . . . Listen not to the teaching of any man, or any elder who says the word of wisdom is of no moment; for such a man will eventually be overthrown. . . . I know that nothing but an unwavering, undeviating course can save a man in the kingdom of God. [4]

Clearly (at least in this instance), Hyrum relied on questions to provoke people to reflection and, ultimately, action.

At another trying time in the Church when some Saints were apostatizing and causing strife amongst the faithful, Hyrum pondered how best to address the issue. While giving a talk at the general conference of the Church, he asked a crucial question that cut through the numerous arguments, protestations, frustrations, and allegations being bandied about regarding Joseph’s role as Prophet. He addressed the question to all in attendance: “How should any man prosper whilst seeking to injure him whom God had blessed and promised to protect and concerning whom the prophets had prophesied that he should live to fulfil the work committed to him?” [5]

It is recorded that Hyrum went on to encourage the Saints to go forward without fear. [6] His question parted the mists of darkness that were swirling in many minds and helped listeners reconnect with their deepest, truest beliefs and testimony. Hyrum then called “for all those who were willing to support and uphold Joseph and who believed that he was doing his duty and was innocent of the charges &c to hold up their right hand whereupon almost every person present was seen with their hands elevated and their countenances beaming with joy. Afterwards he said if there were any who were opposed to Joseph and would not defend him let them manifest it by the same sign but there was not one opposing witness.” [7]

A powerful principle we learn from Joseph and Hyrum about edifying leadership is the importance of asking authentic questions to our Heavenly Father, others, and ourselves. Joseph and Hyrum’s leadership emphasized several kinds of authentic questions that stretch our souls: questions for solace, questions for guidance, and questions for others.

Questions for Solace

God’s wise response to Joseph’s profound, personal question that he asked in the Sacred Grove ultimately rocked the religious world and provoked even more troubling questions for a fourteen-year-old: “Why should the powers of darkness combine against me? Why the opposition and persecution that arose against me, almost in my infancy?” Joseph was wont to swim in deep water (see D&C 127:2) because he dared to ask questions, to which the powers of heaven and hell predictably responded. Joseph did not expect others to react in rage to his personal conversation with God; [8] but he did received rage from others, to the point that he later defined his destiny as being “a disturber and annoyer of [Satan’s] kingdom” (Joseph Smith—History 1:20). [9]

Indeed, sincere questions inevitably disrupt the adversary’s kingdom. Such questions posed with sincere intent, with nothing wavering, let heaven’s edifying light distill upon our souls, as well as upon those who follow us. This doctrine of distillation itself emerged from another profound question Joseph and Hyrum each posed almost two decades later.

Fast-forward, if you will, twenty-four years from the Sacred Grove to Liberty Jail, a “temple-prison” where Joseph’s and Hyrum’s hope was nearly crushed under the weight of their circumstances. The Saints’ sufferings were indescribable, even horrific. They had been driven out of their homes in the dead of winter. Women had been abused. Families had been forced to trek without shoes across sharp ice and snow. In the midst of all this, Joseph and Hyrum knew that very bad things were happening to very good Saints (at least they knew as much as they could gather through secondhand accounts). In this late-winter trial of heart-wrenching despair, Joseph and Hyrum could do precious little to alter their circumstances.

In this dark hour of their lives, Joseph and Hyrum faced some of the most soul-stressing questions of their lives. First, Hyrum pressed his private plea in a letter to his wife, Mary Fielding: “O God, how long shall we suffer these things?” [10] Shortly thereafter, Joseph penned a similar question regarding the Saints at large: “O Lord, how long shall they suffer these wrongs?” (D&C 121:3). These “how long” inquiries echo the Savior’s question, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46), uttered as he likely bore once again—and this time utterly alone—the full weight of all sin and sorrow on the cross of Golgotha. Indeed, “all these things shall give thee experience” (D&C 122:7).

Feeling a heart-wrenching sense of abandonment, Joseph and Hyrum pleaded with every feeling of their hearts, “O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?” [11] (D&C 121:1). This was not a question born from doubt about God’s existence, mercy, or justice. Rather, these poignant words manifested a whole-souled yearning for relief, for perspective, for solace, and ultimately, for deliverance from evil. Just as Joseph and Hyrum, we are also most likely to wonder “why?” and “where art thou?” when faced with adversity; we are also most likely to wonder “why” when unexpected, heartbreaking experiences such as death, divorce, depression, or abuse deeply impact our lives or the lives of loved ones.

Hopefully, we can respond to despairing whys with equally faithful ones, as exemplified by Hyrum’s search for lessons from Liberty. He shared with his wife that Joseph, son of Jacob, “was sold by his brethren . . . [and] cast into prison for many years, yet the power of wisdom was there . . . [and] taught him the knowledge of holy things [and] lifted him up on high. Why? Because he was patient in tribulation and hastened to that redeeming power that saves the righteous in all ages of the world.” [12] Hyrum’s why provides an honest escape from the often heavy whys that arise from the calamities of life. Indeed, he sought wisdom with his why.

For Joseph and Hyrum, their deepest trials often followed nearly identical paths, when heartfelt questions arose to God in duplicate from the depths of their souls. No wonder the powers of heaven were not stayed as both passionately pursued the same light.

Questions for Guidance

Though Joseph and Hyrum ultimately emerged alive from Liberty Jail, they did not escape the Martyrdom, which followed their single simple question: “What shall we do?” [13] Joseph and Hyrum had passed this question back and forth with great spiritual care throughout life, and ultimately their constant, honest pursuit of it created conditions for their death.

Hyrum likely asked this question first as they traveled together in Zion’s Camp from Kirtland to Missouri, when not only they but most on the journey were caught in cholera’s grip with little hope of escape. In this moment of potential despair, “Hyrum cried out, ‘Joseph, what shall we do? Must we be cut off from the face of the earth by this horrid curse?’” “‘Let us,’ said Joseph, ‘get down upon our knees and pray to God to remove the cramp and other distress and restore us to health, that we may return to our families.’” [14] Ultimately, their prayers, combined with the prayers of their mother, opened the healing heavens.

When Hyrum asked Joseph the honest question “What shall we do?” (or when Joseph asked Hyrum the same), the answer always centered on seeking what God wanted them to do. Just as Jesus’ question, “Wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?” (Luke 2:49) framed the balance of the Savior’s mortal life; Joseph and Hyrum’s shared question, “What shall we do?” often prompted one or the other to seek God’s will and then to act in obedience to the answer, even if it be unto death.

As Joseph’s and Hyrum’s earthly ministry approached an end, “What shall we do?” framed their final moments, with Joseph probing Hyrum’s heart for guidance and direction. The situation was perilously dark in Nauvoo, where the forces of evil surrounded and threatened the Saints. Joseph asked Hyrum whether they should turn themselves in to the mob. Hyrum responded:

Just as sure as we fall into their hands we are dead men.” Joseph then asked his older brother what they should do but Hyrum could only echo Joseph’s uncertainty, answering, “I don’t know.” . . . All at once Joseph’s countenance brightened up and he said, “The way is open. It is clear to my mind what to do. All they want is Hyrum and myself; then tell everybody to go about their business, and not to collect in groups, but to scatter about. There is no doubt they will come here and search for us. Let them search; they will not harm you in person or property, and not even a hair of your head. We will cross the river tonight, and go away to the West. [15]

Joseph and Hyrum followed the inspiration and crossed the river on June 22. Then on the western banks of the Mississippi, they revisited their question again, with Joseph asking Hyrum, “‘Brother Hyrum, you are the oldest, what shall we do?’ Hyrum replied, ‘Let us go back and give ourselves up and see the thing out.’ After pondering a few moments, Joseph responded, ‘If you go back, I will go with you, but we shall be butchered.’ Hyrum answered enigmatically, ‘No, no; let us go back and put our trust in God and we shall not be harmed. The Lord is in it. If we live or have to die, we will be reconciled to our fate.’” [16] With this, the brothers returned to meet their martyrdom in Carthage.

Questions for Others

Shortly before the Martyrdom, Joseph probed the Saints with one of the most powerful, life-changing questions ever asked, a question that arguably framed the lives and the leadership of Joseph and Hyrum. Joseph asked all the Saints to consider the following question in their own hearts:

What kind of a being [is] God . . . ? Ask yourselves; turn your thoughts into your hearts, and say if any of you have seen, heard, or communed with Him? This is a question that may occupy your attention for a long time. I again repeat the question—What kind of a being is God? Does any man or woman know? Have any of you seen Him, heard Him, or communed with Him? Here is the question that will, peradventure, from this time henceforth occupy your attention. The scriptures inform us that “This is life eternal that they might know thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom thou hast sent.”

If any man does not know God, and inquires what kind of a being He is—if he will search diligently his own heart—if the declaration of Jesus and the apostles be true, he will realize that he has not eternal life; for there can be eternal life on no other principle. [17]

Joseph and Hyrum’s edifying leadership of the Saints relied on powerful, potential-stretching questions. They not only taught the questions, but they “lived the questions,” as put so well by the poet Rainer Maria Rilke in his letter to a young poet: “Have patience with everything that remains unsolved in your heart. Try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books written in a foreign language. Do not now look for the answers. They cannot now be given to you because you could not live them. . . . At present you need to live the question. Perhaps you will gradually, without even noticing it, find yourself experiencing the answer, some distant day.” [18] Indeed, Joseph and Hyrum lived the questions to help “bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” (Moses 1:39).

Similarly, the Savior’s leadership, as recorded in the scriptures, reflects an equal devotion to the power of questions. [19] He constantly led others to the light with soul-shaping, authentic questions. In fact, one of every nine recorded statements by the Savior in the New Testament involved a question. [20] His questions were direct and at times disconcerting when approached with absolute integrity. Here are a few that have touched particularly resonant chords in our souls:

“What seek ye?” (John 1:38).

“Whom say ye that I am?” (Matthew 16:15).

“What shall a man give in exchange for his soul?” (Mark 8:37).

“For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye?” (Matthew 5:46).

“Why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?” (Matthew 7:3).

“Why are ye so fearful?” (Mark 4:40).

“Where is your faith?” (Luke 8:25).

“What will ye that I shall do unto you?” (Matthew 20:32).

“Believest thou this?” (John 11:26).

“Do ye now believe?” (John 16:31).

“What, could you not watch with me one hour?” (Matthew 26:40).

“Have ye your heart yet hardened?” (Mark 8:17).

“Lovest thou me?” (John 21:16).

Jesus cares deeply about our authentic, individual answers. He does not want responses based on borrowed light or false sincerity. Ultimately, his questions invite us to come to know him with all our heart, might, mind, and strength.

Finally, what greater questions are there than those posed by our Heavenly Father to Adam and Eve? When Satan had deceived them into partaking of the forbidden fruit, both hid from God. In response, Heavenly Father asked, “Where art thou?” (Genesis 3:9) and “Where goest thou?” (Moses 4:15)—even though he knew precisely where they were and where they were going. These questions were specifically intended for Adam and Eve in their moment of transgression, just as they can benefit us in moments of weakness today. These questions also communicate with clarity the depth of our Heavenly Father’s eternal life and leadership. He knows where he is and where he is going, and as a result, his work and glory as Leader and Father center on helping us remember and live well the same questions.

Life Sermons from Questions

Joseph and Hyrum “let their lives speak” [21] even unto death. Arguably, the most powerful sermons they ever spoke (in word and deed) emerged from the profound questions they lived. Their questions often surfaced from the thunderstorms of adversity and uncertainty that were hallmarks of their mortality. Truly, both were “wont to swim in deep water” [22]—in which any disciple of Christ swims. When the storms descended on Joseph and Hyrum, each asked defining questions that framed their lives and leadership.

Imagine, for a moment, the leadership legacy of Joseph and Hyrum if they had not persisted in the pursuit of any one of these profoundly, personal questions:

- Which church is right?

- Why should the powers of darkness combine against me?

- O God, where art thou?

- How long shall we suffer these things?

- What shall we do?

- What kind of a being is God?

Each question left its indelible mark on their lives and their leadership. Each defined who they were as leaders, then and now. The first question, “Which church is right?” opened the door of this final dispensation, for Joseph personally as well as for all of God’s children. It set the path for Joseph and Hyrum to continue asking for wisdom when faced with uncertainty.

The second question, “Why should the powers of darkness combine against me?” points out the adversary’s intention to derail this dispensation by opposing Joseph and Hyrum personally, as well as anyone else set on choosing the right.

The third question, “O God, where art thou?” reinforces the reality of the gospel plan, wherein we are free to choose for ourselves; as part of that plan, we are sometimes left to ourselves to experience the effects of good and evil.

The fourth question, “How long shall we suffer these things?” refers to the transforming power of crucibles as Joseph and Hyrum swam through the “deep water” of adversity and suffering, as other Saints past and present also swim.

The fifth question, “What shall we do?” demonstrates the daily discipleship that Joseph and Hyrum practiced on a regular basis, a commitment that manifested itself repeatedly as they regularly asked each other to seek God’s will in their lives.

The final question, “What kind of being is God?” brought Joseph full circle back to the first question, “Which church is right?” where the answer gave Joseph face-to-face experience with God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ. Both Joseph and Hyrum knew that “this is life eternal, that they might know . . . the only true God” (John 17:3); they knew that to know what kind of being God is has been the goal of mankind for time and eternity. They taught the Saints by word and deed to seek for themselves to know who God really is and to experience firsthand the difference such knowledge can make in everyday life.

Clearly, questions played a pivotal role in Joseph’s and Hyrum’s work as leaders. In fact, their dogged pursuit of these and other questions defined their lives as leaders. Equally important, their leadership and life-defining questions can cast a legacy of light upon us as we follow their example of asking God in search of wisdom. By doing so with integrity, our questions—and more importantly our pursuit of these questions—will ultimately help define who we are, which in the end becomes the most powerful leadership legacy of all.

When Satan commanded Moses to worship him, Moses asked, “Who art thou?” (Moses 1:13). In essence, he wanted to know, “What do you really care about, Satan?” Then and now, the questions that we personally pursue as leaders (and that ultimately live in our lives) offer profound clues to followers about what matters most. Indeed, knowing the questions we live (and often ask ourselves or others) helps us better define and refine our leadership. Joseph’s and Hyrum’s questions and the life choices that reflected them cast light upon their followers, while the adversary’s self-centered questions—either directly, as he did to Eve when he asked, “Hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden?” (Genesis 3:1), or indirectly through Cain “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Moses 5:34)—cast nothing but shadow and deception. Such shadows were obvious to Moses as he wisely observed, “Where is thy glory, for it is darkness unto me” (Moses 1:15).

Clearly, a critical leadership task is to surface and define our own questions, “to know as [we] are known” (D&C 76:94), since such questions define who we are and how we lead. Such questions define our leadership. For example, perhaps no other question reflects with greater precision the life and leadership of Nephi than “Have ye inquired of the Lord?” (1 Nephi 15:8). And the question that defines the premortal, mortal, and postmortal mission of the Savior best may be “Wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?” (Luke 2:49).

The Power of Questions

Prominent secular leaders also ask great questions of themselves and others. Such questions serve as catalysts for changing who we are and what we do, opening up new avenues of action. [23] Indeed, as Peter Drucker once put it: “The important and difficult job [of leadership] is never to find the right answer, it is to find the right question. For there are few things as useless—if not as dangerous—as the right answer to the wrong question.” [24] As leaders at home, church, work, or in society, it is important to ask ourselves: What questions matter most to me? What questions do I regularly ask, either to myself or to others? What questions does my life reflect as being most important to me?

As leaders it is not only important to ask questions, but it is equally important to create an environment where others can ask their questions of deep significance. [25] In other words, do we create an environment where others ask their most perplexing and personal questions? If not, we need to create such a space—an emotional, psychological, and perhaps even physical place—where others can comfortably inquire, discover new (and perhaps unsettling) insights, and then use their God-granted agency to act upon the insights. In essence, leadership work is about creating a space where insight emerges and engages just as it did for Joseph in the Sacred Grove.

Asking and eliciting good questions does make a difference in delivering leadership results. For example, highly effective international negotiators ask more questions than do less-effective ones. [26] Highly effective innovators ask more questions—especially status-quo challenging questions—than those less likely to innovate (for example, in creating new businesses, products, and services and new ways of doing things). [27] Even on the political field, leaders often use questions to change the world.

Abraham Lincoln, arguably one of the most successful presidents of the United States, was also the most frequent questioner—at least when it came to delivering inaugural speeches framing the start of a new leadership era. [28] Consider Lincoln’s attempt to avert a civil war by asking several provocative questions in hopes that the people would change their course of action:

That there are persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union at all events and are glad of any pretext to do it I will neither affirm nor deny; but if there be such, I need address no word to them. To those, however, who really love the Union may I not speak? Before entering upon so grave a matter as the destruction of our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes, would it not be wise to ascertain precisely why we do it? Will you hazard so desperate a step while there is any possibility that any portion of the ills you fly from have no real existence? Will you, while the certain ills you fly to are greater than all the real ones you fly from, will you risk the commission of so fearful a mistake? . . .

Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world? . . . My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well upon this whole subject. Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time. If there be an object to hurry any of you in hot haste to a step which you would never take deliberately, that object will be frustrated by taking time; but no good object can be frustrated by it. . . .

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature. [29]

Unfortunately, many in Lincoln’s audience were unwilling to reflect on his authentic questions in search of authentic answers; a tragic civil war ensued just as Joseph Smith had prophesied: “Wars . . . will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina, which will eventually terminate in the death and misery of many souls” (D&C 87:1).

There is no doubt that the world needs leaders capable of changing the status quo, leaders prepared and capable of making it a better place. Indeed, we believe that we can change the world by changing our questions, just as John F. Kennedy once proposed: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” [30] In the same spirit, President Gordon B. Hinckley wisely counseled, “What we desperately need today on all fronts—in our homes and communities, in schoolrooms and boardrooms, and certainly throughout society at large—are leaders, men and women who are willing to stand for something.” [31] President Brigham Young stated simply how we can accomplish this: “It is the duty of a Saint of God to gain all the influence he can on this earth, and to use every particle of that influence to do good. If this is not his duty, I do not understand what the duty of man is.” [32]

Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s life-defining questions were an important part of their profound leadership influence—even to this day. Their questions, like those of the Savior, set an example for any leader lacking wisdom. They truly believed that “if any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God” (James 1:5); and ask they did! And they not only received wisdom from heaven but they also used that wisdom to live and lead wisely. Indeed, they lived the questions that mattered most and by so doing made a profound impact on the world. May we honor their example by always doing the same, by asking of God in faith.

Notes

[1] Truman G. Madsen, Defender of the Faith: The B. H. Roberts Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 116.

[2] Madsen, Defender of the Faith, 116.

[3] Cecil O. Samuelson, “The Importance of Asking Questions,” Brigham Young University 2001–2002 Speeches (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 2002), 150–52.

[4] Hyrum Smith, Times and Seasons, June 1, 1842, 800.

[5] The Papers of Joseph Smith, Vol. 2: Journal, 1832–1842, ed. Dean C. Jessee (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 420; punctuation and spelling modernized.

[6] Smith, Papers of Joseph Smith, 420.

[7] Smith, Papers of Joseph Smith, 421.

[8] Socrates found himself in a similar situation when his honest questions provoked hostile responses to the point that he drank deadly hemlock to carry out the democratic government’s death sentence in Athens, 399 BC (See Michael J. Gelb, Socrates’ Way [New York: Tarcher/

[9] We suspect that not only then but also now, Joseph continues to play the role of disturber of Satan’s kingdom as the lead Prophet in the final dispensation.

[10] Quoted in Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith: A Life of Integrity (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 197.

[11] Ancient prophets faced similar feelings (see, for example, Isaiah 45:15).

[12] Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, quoted in O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 193; emphasis added.

[13] This same, simple question has been posed throughout time. For example, it was posed to the Savior by his followers during his earthly ministry (see Luke 3:10), to Paul by the people of Jerusalem (see Acts 2:37), and to Alma by the poor in substance, but not spirit (see Alma 32:5). Interestingly, this final question was simply a slight twist on Joseph’s first question, “What is to be done?” when preparing for his first vocal prayer.

[14] Lucy Mack Smith, The Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith by His Mother, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 318; emphasis added.

[15] O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 339–40.

[16] O’Driscoll, Hyrum Smith, 342; emphasis added.

[17] From the King Follett discourse, delivered April 7, 1844 (Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev., [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957], 6:303–4); emphasis added.

[18] Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. Joan M. Burnham (Novato, CA: New World Library, 2000), 35; emphasis in original.

[19] Dennis Rasmussen, The Lord’s Question: Thoughts on the Life of Response (Provo, UT: Keter Foundation, 1985).

[20] This ratio is based upon the personal research of Hal B Gregersen, who analyzed all the statements by the Savior in the New Testament and comparing those ending with a period or exclamation point with those ending with a question mark.

[21] Parker J. Palmer, Let Your Life Speak (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000).

[22] See Personal Writing of Joseph Smith, 544.

[23] Marilee C. Goldberg, The Art of the Question (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998); Michael Marquardt, Leading with Questions (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

[24] Peter Drucker, The Practice of Management (New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1964), 353.

[25] J. T. Dillon, Questioning and Teaching: A Manual of Practice (New York: Teachers College Press, 1988).

[26] Nancy J. Adler and Allison Gundersen, International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior (Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western, 2007).

[27] Jeffrey H. Dyer, Hal B. Gregersen, and Clayton M. Christensen, “The Innovator’s DNA,” Harvard Business Review, forthcoming; Jeffrey Dyer, Hal B Gregersen, Clayton M. Christensen, “Differences Between Innovative Entrepreneurs and Managers: Behavioral Patterns that Facilitate Opportunity Recognition.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2, (2008): 317–38.

[28] Lincoln showed the highest question-to-answer ratio (in other words, the number of questions compared to statements) made during an inaugural address of any U.S. President (to review Lincoln’s specific questions, see http://

[29] Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861. http://

[30] John F. Kennedy, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961, http://

[31] Gordon B. Hinckley, Standing for Something (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2000), 197.

[32] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 12:376.