Joseph Smith and the Papyri

Joseph Smith Jr., first prophet and president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, worked on the Book of Abraham in 1835 and 1842. Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

Joseph Smith Jr., first prophet and president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, worked on the Book of Abraham in 1835 and 1842. Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

Most of the interest in the Joseph Smith Papyri comes from what people think Joseph Smith may or may not have done with or said about them. Finding out what Joseph Smith actually said or thought about the papyri is a complicated matter. The historical record has flashes of incomplete information but usually does not provide us with the information we would like to know. Individuals who deal with the history must usually bring in assumptions about what occurred, many of which may be false and most of which cannot be proven.

One of the assumptions people often make concerns what material is attributed to Joseph Smith. On one end of the spectrum are those who will attribute as much as possible to Joseph Smith, even if we know that he did not say or do it. For example, many attribute the artwork of the facsimiles, which is long known to have been done by Reuben Hedlock, to Joseph Smith. At the other end are those who will not attribute anything to Joseph Smith unless it can be proven that he said it or did it. While such a minimalist approach certainly excludes many real deeds and sayings of Joseph Smith, it is the safer scholarly approach and avoids unnecessary speculation. Here we will examine what Joseph Smith did with the papyri, moving from the more certain to the more speculative.

History of the Translation of the Book of Abraham

Joseph Smith began translating the papyri in early July 1835, with Oliver Cowdery and William W. Phelps serving as his scribes. The current published text of the Book of Abraham, and probably more, seems to have been translated by the end of July 1835; the Book of Abraham appears to have been longer than the current text. In August 1835, Joseph Smith left Kirtland to visit the Saints in Michigan, and no translation was done during the trip. Revelation pertaining to the Book of Abraham was not known to have been received again until 1 October 1835. Translation continued intermittently through 25 November 1835, but Joseph then set aside the papyri to study Hebrew, finish and dedicate the Kirtland

An artistic representation of the golden plates, breastplate, and Urim and Thummim, based on descriptions by Joseph Smith and others. Created by David A. Baird, Courtesy of Historical Arts and Casting. Wikimedia Commons.

An artistic representation of the golden plates, breastplate, and Urim and Thummim, based on descriptions by Joseph Smith and others. Created by David A. Baird, Courtesy of Historical Arts and Casting. Wikimedia Commons.

Temple, and, later, deal with troubles in Missouri. Joseph revised the translation preparatory to its publication in 1842, but other than that, no evidence has survived that he worked on the translation of the existing Book of Abraham after 1835. Unfortunately, Joseph was extremely busy and consequently somewhat haphazard in his record keeping, so we cannot be certain.

We do not know if the translation of the Book of Abraham was ever completed, but we do know the publication was not. The second installment in the Times and Seasons in 1842 ends with the words “to be continued,” but it never was. None of the extant manuscripts of the Book of Abraham even cover as much as the printed text.

Despite much speculation, the process Joseph Smith used to translate the Book of Abraham is unknown; we have no record of Joseph Smith himself discussing what methods he used. We have no firsthand evidence that Joseph Smith used the Urim and Thummim or a seer stone in translating the Book of Abraham. Some thirdhand accounts claim he did, but those accounts do not come from anyone who actually observed the translation. Nor did Joseph Smith apparently use any grammars or dictionaries in preparing his translations. Nevertheless, we do have an account from Warren Parrish, one of the scribes involved in the translation during late 1835. He wrote, “I have set by his side and penned down the translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphicks as he claimed to receive it by direct inspiration of Heaven.”[1] This is the only recorded statement of anyone directly involved in the translation about how it was done.

Joseph Smith’s Translation Methods

Over the course of Joseph Smith’s life, the way that he translated texts changed. Looking at what we know of the translation of the Book of Abraham in the context of Joseph Smith’s translations of ancient texts shows that it fits well into his development as a translator.

When Joseph Smith began translating the Book of Mormon in 1827, he usually left the plates in a box or wrapped in a cloth, placed the interpreters or his seer stone (both of which seem to have been called Urim and Thummim) in a hat, and read the translation he saw in the stone to a scribe. He received many of his early revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants the same way. When the first 116 pages of the Book of Mormon were stolen, an angel took back the interpreters, and Joseph instead used his seer stone. By the time that Joseph finished translating the Book of Mormon in 1829, he no longer needed to use the Urim and Thummim to receive revelation.

When he provided a translation of a papyrus for the seventh section of the Doctrine and Covenants, he did not have physical possession of the papyrus he was translating.

When he did his translation of the Bible from 1830 to 1833, he used neither the Urim and Thummim nor any manuscripts in the original languages to do so. At the beginning of this translation, Joseph Smith would dictate long passages to his scribe without the use of the Urim and Thummim. When Sidney Rigdon began serving as a scribe, however, he apparently persuaded Joseph to change his practice and mark only passages in the Bible that needed changes and record those.

His translation of the Book of Abraham, apparently without Urim and Thummim, dictionary, or grammar, and “by direct inspiration of Heaven,” fits comfortably into the historical pattern of his translations.

The first time Joseph Smith appears to have used any kind of grammar or dictionary was when he began to learn Hebrew, starting in late 1835 but mostly in 1836, after the current portion of the Book of Abraham seems to have been translated. When studying Hebrew, Joseph Smith appears to have done translation in the normal way by studying the grammar and the dictionary and producing a translation with those aids under the tutelage of a Hebrew teacher, Josiah Sexias.

Though Joseph Smith did occasionally write for himself, he preferred to dictate to associates who served as scribes. These other individuals, however, also thought for themselves and wrote their own works. Most of the scribes who assisted in the translation of the Book of Abraham (Oliver Cowdery, W. W. Phelps, and Warren Parrish) had been promised in blessings that they could translate ancient texts. Consequently, though Joseph used scribes, not everything written by someone who served as his scribe is necessarily by Joseph Smith.

The documents Joseph Smith dictated in 1835–36 were from one to seventeen pages in length. The manuscripts of the Book of Abraham dating to that time vary in length, between one and ten pages of text, all of which fit within the range of what Joseph Smith was known to dictate in a single day at that time. Even under the assumption that we have all the manuscripts and assuming that the differences between them account for different translation sessions, we can account for only three hypothetical translation sessions (presumably Abraham 1:1–3, 1:4–2:6, 2:7–18), and we have six recorded in his journal. This is another indication that the manuscripts are incomplete.

So, given Joseph Smith’s development as a translator and the historical time period when the translation of the Book of Abraham occurred, we would expect that Joseph Smith would translate simply by receiving inspiration—without the Urim and Thummim—and dictating the translation to a scribe, covering between one and seventeen pages at a time. Use of a grammar and a dictionary seems to have been foreign to his methods until after he studied Hebrew in 1836. What little we know of the translation of the Book of Abraham seems to fit this pattern.

History of the Publication of the Book of Abraham

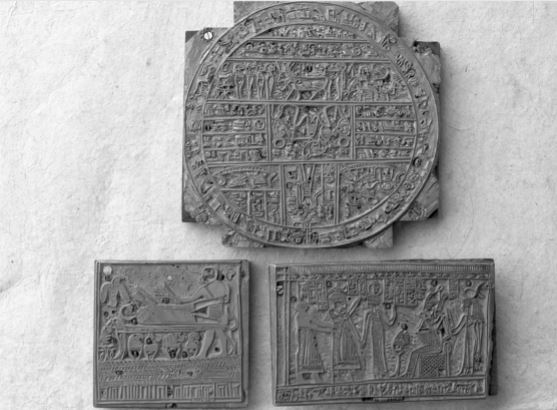

In early 1842, Joseph Smith, Willard Richards, and Reuben Hedlock prepared the text for publication in the Times and Seasons. Each installment of the Book of Abraham was accompanied by an illustration called a facsimile from the Book of Abraham. The three facsimiles made to accompany the translation of the Book of Abraham were cut to actual size by Reuben Hedlock. Only three installments were published, which together included what has been estimated to be about one-quarter to one-third of what Joseph Smith translated. The last installment published in the Times and Seasons ends with the statement “to be continued.” Unfortunately, the location of the original manuscript of his translation is currently unknown, and thus, according to the estimate, about two-thirds to three-quarters of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Abraham is lost.

The original printing plates of the facsimiles from the Book of Abraham, produced in 1842 by Reuben Hedlock and corresponding to the size of the original papyrus documents. While facsimiles I and 3 derive from vignettes form the same short papyrus and are thus the same height. Facsimile 2 comes from a taller papyrus document. Walden C. Andersen.

The original printing plates of the facsimiles from the Book of Abraham, produced in 1842 by Reuben Hedlock and corresponding to the size of the original papyrus documents. While facsimiles I and 3 derive from vignettes form the same short papyrus and are thus the same height. Facsimile 2 comes from a taller papyrus document. Walden C. Andersen.

In the absence of textual or historical evidence, speculation about what the fuller Book of Abraham might have contained is interesting and sometimes well-reasoned. Speculation is a dangerous basis upon which to build theories and should not be mistaken for fact. In the book of Genesis, the story of Abraham covers from Genesis 11:27 to Genesis 25:10; yet the Book of Abraham ends at about the equivalent of Genesis 12:13. Presumably, much more of Abraham’s life might have been covered if it had been published. We can only speculate about where it might have ended. Though there are some lines of argument that would have had it end after the events in Genesis 22, we do not know if that would have actually been the case.

In 1851, Franklin D. Richards— then the newest Apostle of the Church and the new president of the European Mission, headquartered in England— found that the Church members in England, the location with the largest number of Latter-day Saints in the world at the time, had almost no Church literature. Elder Richards included the Book of Abraham in “a choice selection from the revelations, translations, and narrations of Joseph Smith,” published as the Pearl of Great Price.[4] It was “not adapted, nor designed, as a pioneer of the faith among unbelievers”; instead, it was designed for the Saints “to increase their ability to maintain and defend the holy faith by becoming possessors of it.”[5] The facsimiles of the Book of Abraham were recut with this edition and succeeding editions, becoming increasingly more inaccurate with subsequent editions.

In 1878, the Pearl of Great Price was published in Utah. Two years later it was canonized by a vote of the general conference of the Church. The 1907 edition had the most inaccurate copies of the facsimiles, and they continued to be used until the 1981 English edition restored Hedlock’s original facsimiles. The 1981 edition has been the standard edition ever since. The 2013 edition has only minor changes.

The Manuscripts of the Book of Abraham

There are seven known manuscripts of the Book of Abraham; none of them are the original, and none of them are complete. Most of the extant manuscripts come from the first and second chapters and thus do not cover the entire portion of the Book of Abraham that had been translated at the time that they were produced. More than half of the published Book of Abraham is not attested in any surviving manuscript.

- Although Oliver Cowdery and William W. Phelps were the scribes for the initial portion of the translation of the Book of Abraham in July 1835 and early October 1835, none of the manuscripts are in the handwriting of Cowdery, and only three verses on one manuscript are in the handwriting of Phelps.

- The earliest surviving manuscript of the Book of Abraham, probably written in early October 1835 in the handwriting of Frederick G. Williams, contains a long dittography (a repetition of part of the manuscript), which is characteristic of copied manuscripts—not dictated ones. (Joseph Smith’s scribes at the time made dittography errors in both copied and dictated texts, but the longest dittography in a text from 1835 to 1836 known to be dictated is three words. Longer dittography errors otherwise occur only in copied texts.)

- In the Kirtland period, there are more translation sessions recorded in Joseph Smith’s journal than can be accounted for in the surviving manuscripts.

- References to the content from later sections of the Book of Abraham (e.g., Shinehah from Abraham 3:13) show up after the translation commenced but come from sections later in the translation than the manuscripts surviving from Kirtland.

- Joseph Smith mentions in his journal that he revised the translation of the Book of Abraham in 1842 just before publication, but none of the manuscripts seem to contain these revisions. There are places where the published text differs from the manuscripts, but no manuscript shows additions, deletions, or corrections that bring the text on the manuscript in line with what was eventually published.

- Nineteenth-century eyewitnesses say that Lucy Mack Smith “had pasted the deciphered sheets on the leaves of a book which she showed us” in 1846.[6] Only one of the known manuscripts is part of a book—the William Appleby Journal—and it was not in the possession of Lucy Smith.

These manuscripts tell us something about the translation process, but they are not extensive enough to tell us much, and they do not tell us as much as they might if they were the originals. The manuscripts point to some revision during the translation process. Unlike the Book of Mormon, the manuscripts show some recasting of language in the translation. One of these changes may tell us something about the original language of the Book of Abraham. The earliest manuscript containing Abraham 1:17 reads, “and this because their hearts are turned they have turned their hearts away from me.” The phrase “their hearts are turned” was crossed out and, “they have turned their hearts” was written immediately afterwards. The two phrases would be identical in the Egyptian of the papyri, so this may be an indication that Joseph Smith was translating from Egyptian.

Most of the extant Book of Abraham manuscripts seem to have been personal copies of portions of the Book of Abraham made for their owners. This can be seen in examining who had each particular manuscript. The main manuscript seems to have been part of a book that was kept by Lucy Mack Smith until her death in 1856. One of the manuscripts was in the possession of Joseph Smith’s family, and it consists of a few loose, unbound pages. William Appleby recorded some of the Book of Abraham in his journal. The rest of the manuscripts were brought to Utah by Willard Richards and W. W. Phelps, who were Church historians but also had their own personal materials. Willard Richards seems to have made a copy to take to the printer and kept some of those pages.

Other Potentially Associated Manuscripts

Along with the Book of Abraham manuscripts that Richards and Phelps brought to Utah are other manuscripts. These manuscripts have been known under a number of names, such as “the Kirtland Egyptian Papers” or “the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language.” The name designations are modern ones and typically reflect assumptions of the individuals using the particular designations. No designation has gained wide acceptance. Almost every aspect of these documents is disputed: their authorship, their date, their purpose, their relationship with the Book of Abraham, their relationship with the Joseph Smith Papyri, their relationship with each other, what the documents are or were intended to be, and even whether the documents form a discrete or coherent group. With so many questionable or problematic facets of the documents in dispute, theories about the Book of Abraham built on this material run the risk of following a potentially incorrect assumption to its logically flawed conclusion. The only things about the manuscripts that are not disputed are their provenance, and (with one exception) the handwriting of the document. Yet, while the handwriting of the document is not disputed, whether the individual writing the document was serving as author or scribe is.

While these documents are kept together, often classed together, and, additionally, often classed with Book of Abraham manuscripts, that classification is artificial. To understand this, one must know the difference between a dossier and an archive. A dossier is a group of documents gathered by historians in modern times because they are seen as related in some way. An archive is a group of documents that was originally assembled by an individual for his or her own purposes. Both dossiers and archives are valuable in research and address different issues and problems. This group of manuscripts now kept together in Church archives is a dossier and not an archive. Since the provenance of the documents is not disputed, it can be used to separate the dossier of documents into discrete archives.

We know that one of the Book of Abraham manuscripts came from Joseph Smith because it passed from him, to his wife, to her second husband’s family, who sold it to Wilford Wood, who gave it to the Church. The other documents of this dossier came from Willard Richards and W. W. Phelps. The documents form at least two separate archives, one of which belonged to Joseph Smith. Of the other documents, the ones in Willard Richards’s hands form a separate group on their own. They all share the same handwriting and deal with different materials and subjects than the other documents; they seem to have been the printer’s manuscript for the publication of the Book of Abraham. On that basis, they can be considered a distinct archive in the larger dossier.

The rest of the collection (which includes more than just Book of Abraham manuscripts) is known to have been in Phelps’s possession, and most of the documents are in his handwriting. Joseph Smith’s journal also seems to indicate that the documents belonged to Phelps. On 9 November 1843, Joseph Smith received a letter from James Arlington Bennet and, not having the time to draft a response, “gave instruction to have it answerd” by W. W. Phelps in his name.[7] Phelps spent three or four days working on the draft and showed off his own language prowess, in the course of which he quoted some of his own speculation on the Egyptian documents from the manuscripts in his possession. On the morning of 13 November 1843, “Phelps read [the] letter to Jas A Bennet. & [Joseph Smith] made some correcti[o]ns.”[8] Apparently, the Egyptian quotation bothered Joseph Smith because that afternoon he “called again & enqui[re]d for. the Egypti[a]n grammar,” [9] apparently to check what Phelps had quoted. Two days later Joseph Smith “suggested the idea of preparing a grammar of the Egyptian Language;” [10] it sounds like he may not have agreed with Phelps’s treatment. Phelps’s treatment is based on his attempt to reconstruct the Adamic language in early 1835.

| Church History Archival Number | Book of Abraham Manuscript Number | Contents | Scribe | Date | Dating Criteria | Archive | Provenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS 1294 fd. 1 | Ab1 | Abraham 1:1–3 | W. W. Phelps | Between July 1835 and 29 October 1835 | Joseph Smith | Joseph Smith to Emma Smith to Lewis Bidamon to Wilford Wood to LDS Church Archives | |

| MS 1294 fd. 1 | Ab4 | Abraham 1:4–2:18 | Warren Parrish | Between 29 October 1835 and 1 April 1836 | Parrish’s service as scribe | ||

| MS 1401 fd. 1 | WA | Abraham 1:15–31 | William Appelby | 5 May 1841 | Dated journal entry | William Appelby | |

| MS 1294 fd. 4 | Ab5 | Abraham 1:1–2:18 | Willard Richards | 1842 | Willard Richards | Brought west by Willard Richards and W. W. Phelps | |

| MS 1294 fd. 4 | Ab5a | Facsimile 1 explanation | Willard Richards | 1842 | |||

| MS 1294 fd. 5 | Ab6 | Facsimile 2 explanation | Willard Richards | 1842 | |||

| MS 1294 fd. 5 | Ab7 | Abraham 3:18b–26a | Willard Richards | 1842 | |||

| MS 1294 fd. 2 | Ab2 | Abraham 1:4–2:6 | Frederick G. Williams | Between 3 and 29 October 1835 | Williams‘s service as scribe | W. W. Phelps | |

| MS 1294 fd. 3 | Ab3 | Abraham 1:4–2:2 | Warren Parrish | Between 29 October 1835 and 1 April 1836 | Parrish’s service as scribe | ||

| MS 1295 fd. 3 | Egyptian alphabet | W. W. Phelps | 1 October 1835 | Journal entry matching scribe and title, pre-Sexias transliteration system, characters read from left to right, the word “part” is used for what is now called a “line” or “column” | |||

| MS 1295 fd. 4 | Egyptian alphabet | Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery | 1 October 1835 | Journal entry matching scribe and title, pre-Sexias transliteration system, characters read from left to right, the word “part” is used for what is now called a “line” or “column” | |||

| MS 1295 fd. 5 | [Egyptian alphabet] | Oliver Cowdery | 1 October 1835 | Journal entry matching scribe and title, pre-Sexias transliteration system, characters read from left to right, the word “part” is used for what is now called a “line” or “column” | |||

| MS 1295 fd. 6 | Transcription of portion of Imouthes papyrus | Oliver Cowdery | After July 1835 | ||||

| MS 1295 fd. 7 | Transcription of portion of Imouthes papyrus | Oliver Cowdery | After July 1835 | ||||

| MS 1295 fd. 8 | Transcription of Semminis papyrus | W. W. Phelps(?) | After July 1835 | ||||

| MS 1295 fd. 9 | Transcription of Semminis papyrus | W. W. Phelps(?) | After July 1835 | ||||

| MS 1295 fd. 2 | Egyptian counting | W. W. Phelps | Between July 1835 and January 1836 | Pre-Sexias transliteration system | |||

| MS 1295 fd. 1 | Grammar and aphabet [sic] of the Egyptian language | W. W. Phelps and Warren Parrish | Between January and April 1836 | Post-Sexias transliteration system |

Whatever the extent of Joseph Smith’s involvement with Phelps’s attempt to compile an Egyptian grammar, the order of events is interesting. Phelps’s documents date later than the early Book of Abraham manuscripts. The grammar seems to have been produced from the Book of Abraham and not the other way round. Most people who learn another language learn it by studying a grammar book and using a dictionary. Those who decipher a dead language, however, do not learn the language that way. A decipherer comes up with a translation first, recording insights along the way. Later, scholars gather the insights into the language that the decipherers came up with and systematize them into a grammar book from which others will learn the language. This was the pattern followed in the decipherment of languages such as Egyptian, Akkadian, Sumerian, Hittite, Elamite, Linear B, Luwian, and Mayan. W. W. Phelps and his associates seem to have envisioned the same process with the Book of Abraham: Joseph Smith’s translation coming first and any grammar coming later.

Although we have incomplete information on exactly how the Book of Abraham was translated, the resulting contents of that translation are more important than the process itself.

Further Reading

Gee, John. “Eyewitness, Hearsay, and Physical Evidence of the Joseph Smith Papyri.” In The Disciple as Witness: Essays on Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, 175–217. Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000. This article discusses what can be learned about the Joseph Smith Papyri from nineteenth-century eyewitness accounts of the papyri. It also discusses some of the evidence of what Joseph Smith thought he was doing with the papyri.

———. “Joseph Smith and Ancient Egypt.” In Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell and Matthew J. Grey, 427– 48. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015. This article discusses what Joseph Smith might have known about ancient Egypt and what evidence can be used to learn about Joseph Smith’s knowledge of ancient Egypt. The essay takes a minimalist point of view, using only what can be demonstrated to come from Joseph Smith to reflect his knowledge, rather than a maximalist point of view, which takes anything attributed to Joseph Smith—no matter how tenuously—as reflecting his knowledge.

Hauglid, Brian M. A Textual History of the Book of Abraham: Manuscripts and Editions. Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2011. This book contains photographs and simplified transcriptions of the various manuscripts of the Book of Abraham. The transcriptions are simplified in that not every example of rewriting or retouching is noted. The text is a printing of the 1842 edition of the text with places where the manuscripts or later editions vary from the 1842 text noted in footnotes.

MacKay, Michael Hubbard, and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat. From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2015. The best synthesis so far about Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon. While the Book of Abraham is different in many respects, this book is helpful for understanding Joseph Smith’s trajectory in translation and how he learned to approach translating an ancient text.

Muhlestein, Kerry, and Megan Hansen. “‘The Work of Translating’: The Book of Abraham’s Translation Chronology.” In Let Us Reason Together: Essays in Honor of the Life’s Work of Robert L. Millet, edited by J. Spencer Fluhman and Brent L. Top, 139–62 Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016). An even-handed examination of various points of evidence for the chronology of the translation of the Book of Abraham. Muhlestein essentially confirms the standard chronology followed here.

Notes

[1] Warren Parrish, letter to the editor, Painesville Republican, 15 February 1838, 3.

[2] Blessing for William W. Phelps, 22 September 1835, available at http://

[3] Joseph Smith, Journal 1835–1836, in Joseph Smith Papers: Journals, 1:99–100; Jessee, The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, 83; Jessee, Papers of Joseph Smith, 2:79; Jessee, Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, 112.

[4] The Pearl of Great Price (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1851), title page.

[5] Franklin D. Richards, “Preface,” in The Pearl of Great Price (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1851), v.

[6] M., Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer 3, no. 27 (7 October 1846): 211.

[7] Joseph Smith, Journal, December 1842–June 1844, in Joseph Smith Papers: Journals, 3:127.

[8] Joseph Smith, Journal, December 1842–June 1844, in Joseph Smith Papers: Journals, 3:128.

[9] Joseph Smith, Journal, December 1842–June 1844, in Joseph Smith Papers: Journals, 3:128.

[10] Joseph Smith, Journal, December 1842–June 1844, in Joseph Smith Papers: Journals, 3:130.