Historical Overview

When the Book of Abraham was first published to the world in 1842, it was published as “a translation of some ancient records that have fallen into [Joseph Smith’s] hands from the catacombs of Egypt, purporting to be the writings of Abraham while he was in Egypt, called ‘The Book of Abraham, Written by his Own Hand, upon Papyrus.’”[1] The resultant record was thus connected with the papyri once owned by Joseph Smith, though which papyrus of the four or five in his possession was never specified. Those papyri would likely interest only a few specialists—were the papyri not bound up in a religious controversy. This controversy covers a number of interrelated issues, and an even greater number of theories have been put forward about these issues. Given the amount of information available, the various theories, and the variety of fields of study the subject requires, misunderstandings and misinformation often prevail. It is useful to have a brief overview of the basic history.

Early History of the Papyri

Bernardino Drovetti and his companions, probably December 1818 in Thebes. From left to right: a servant (seated), Antonio Lebolo, Joseph Rossignana, Jean-Jacques Rifaud, Bernardino Drovetti, another servant (seated), Louis-Nicolas Philippe comte de Forbin, Louid Linant de Bellefonds, an unidentified woman, and a Nubian Guide. Drovetti is measuring an ancient Egyptian colossal head with a plumb line. Lithography by Godefroy Englemann (1788-1839). Auguste de Forbin, Voyage dans le Levant (Public Domain), via Wikimedia Commons

Bernardino Drovetti and his companions, probably December 1818 in Thebes. From left to right: a servant (seated), Antonio Lebolo, Joseph Rossignana, Jean-Jacques Rifaud, Bernardino Drovetti, another servant (seated), Louis-Nicolas Philippe comte de Forbin, Louid Linant de Bellefonds, an unidentified woman, and a Nubian Guide. Drovetti is measuring an ancient Egyptian colossal head with a plumb line. Lithography by Godefroy Englemann (1788-1839). Auguste de Forbin, Voyage dans le Levant (Public Domain), via Wikimedia Commons

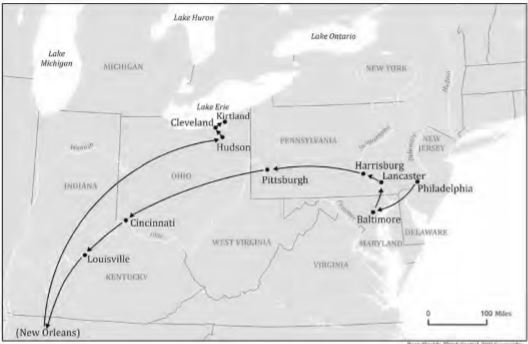

In the early part of the nineteenth century, Bernardino Drovetti was the French consul in Alexandria and was heavily involved in the trade in Egyptian antiquities; his antiquities have ended up in museums all over Europe. He employed a number of individuals who helped him acquire and distribute antiquities. One of his agents was Antonio Lebolo, who, with others, plundered several tombs in Thebes in southern Egypt. In the process, Drovetti’s agents stumbled across a number of Ptolemaic-period burials in Thebes. In 1825 Drovetti commissioned Lebolo to select some of his antiquities to send to America. These included eleven mummies and a number of papyri. Although previously it has been assumed that the papyri were discovered with the mummies, this is not necessarily the case. Records of the excavators say that they kept the papyri separate from the other finds. One mummy had two papyri, one of which went to America and the other to a museum in Europe. Since the papyri were separated from each other, none of the papyri necessarily belonged to the mummy they accompanied.

The antiquities were sent through the shipping company of Albano Oblasser to sell in America. The buyer or buyers are unknown, although the mummies traveled all over the United States from Philadelphia to New Orleans as part of a traveling curiosity show. As it traveled, pieces of the collection were sold off: a skull from one mummy ended up in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and one mummy and papyrus were sold to Junius Booth (the father of John Wilkes Booth); he donated the artifacts to the Smithsonian, but the papyrus was apparently destroyed when the Smithsonian burned in 1865, and the mummy was destroyed at the beginning of the twentieth century. But regardless of whoever originally bought the mummies and papyri, Michael Chandler had possession of them at the end of June 1835 when the mummy show reached Kirtland, Ohio—then headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Known travels of the Joseph Smith Papyri and associated mummies before their purchase by Joseph Smith, based on the research of Brian L. Smith, used with permission.

Known travels of the Joseph Smith Papyri and associated mummies before their purchase by Joseph Smith, based on the research of Brian L. Smith, used with permission.

Joseph Smith, prophet of the Church, examined the papyrus rolls and, after commencing “the translation of some of the characters or hieroglyphics,” said that “one of the rolls contained the writings of Abraham, another the writings of Joseph of Egypt, etc.”[2] In early July of 1835, Joseph Smith (with assistance from Joseph Coe, Simeon Andrews, and others) paid Chandler $2,400 for four mummies and at least four papyrus documents, including two or more rolls of papyri.

Later History of the Papyri

When Joseph Smith bought the papyri, the outer ends of the papyrus scrolls were already damaged. To prevent further damage, the outside portions of some of the papyri were separated from their rolls, mounted on paper, and placed in glass frames in 1837. The remaining portions of the rolls were kept intact. Eyewitnesses describe “a quantity of records, written on papyrus, in Egyptian hieroglyphics”[3] in four groups:

(1) some papyri “preserved under glass,”[4] described as “a number of glazed slides, like picture frames, containing sheets of papyrus, with Egyptian inscriptions and hieroglyphics”;[5]

(2) “a long roll of manuscript”[6] described as the “roll of papyrus from which our prophet translated the Book of Abraham.”[7] It was further described: “The roll was as dark as the bones of the Mummies, and bore very much the same appearance; the opened sheets were exceedingly like thin parchment, and of quite a light color. There were birds, fishes, and fantastic looking people, interspersed amidst hyeroglyphics [sic]”;[8]

(3) “another roll”;[9]

(4) and “two or three other small pieces of papyrus with astronomical calculations, epitaphs, &c.”[10]

Known travels of the Joseph Smith Papyri after they left Joseph Smith's possession.

Known travels of the Joseph Smith Papyri after they left Joseph Smith's possession.

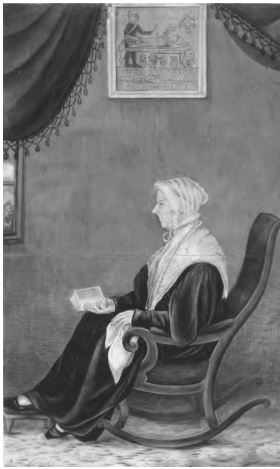

When Joseph Smith relocated to Nauvoo, he turned over the mummies and papyri to his mother, Lucy Mack Smith, to free himself from the obligation of exhibiting the papyri and to provide his widowed mother with means to support herself. She kept the mummies and papyri for the rest of her life, showing them to interested visitors for twenty-five cents a person. On May 26, 1856, less than two weeks after Lucy Mack Smith died, Emma Smith (Joseph’s widow), her second husband (Lewis C. Bidamon), and her son Joseph Smith III sold the mummies and the papyri to a man named Abel Combs.

Abel Combs split up the papyri. Some he sold to the St. Louis Museum, including at least two of the rolls and at least two of the mummies; some of the mounted fragments he kept. The St. Louis Museum sold the rolls and mummies to Colonel Wood’s Museum in Chicago. Wood’s Museum burned down in the Chicago Fire of 1871, and presumably the papyri and mummies were destroyed with it. Wood’s Museum was afterwards rebuilt and acquired other mummies. Its Egyptian collection was later sold to the Niagara Falls Museum, and the Egyptian holdings ended up in the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University; its mummies all date to a different time period than that of the Joseph Smith Papyri.

Lucy Mack Smith, the mother of Joseph Smith Jr., exhibited the mummies and the papyri from before the death of Joseph Smith in 1844 to her own death in 1856. Portrait by Sutcliffe Maudsley, Courtesy of Church History Museum.

Lucy Mack Smith, the mother of Joseph Smith Jr., exhibited the mummies and the papyri from before the death of Joseph Smith in 1844 to her own death in 1856. Portrait by Sutcliffe Maudsley, Courtesy of Church History Museum.

The mounted fragments of papyrus passed from Abel Combs to the hands of Edward and Alice Heusser. In 1918 Alice Heusser offered the papyri to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the time, the museum was not interested. But in 1947 Ludlow Bull, the Metropolitan’s associate curator of the Department of Egyptian Art, purchased the papyri for the museum from Edward Heusser. Notice of the purchase and origin of the papyri was published in the museum’s acquisition list.

After a change in personnel in the Department of Egyptian Art, the museum decided that they did not want the papyri any longer. When Aziz S. Atiya, a Coptic scholar living in Utah, visited the museum in 1966, the curators asked him to see if The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would be interested in the papyri. On 27 November 1967, the Metropolitan Museum presented the fragments of the papyri to the Church. The Church published the papyri two months later in their official magazine, the Improvement Era; the current numbering system of the papyri derives from this publication.

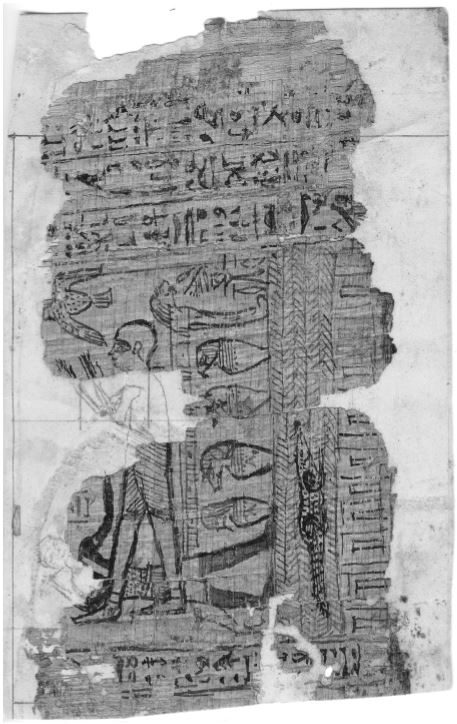

To the disappointment of many, although these remaining fragments contained the illustration that served as the basis for Facsimile 1, they were not the portion of the papyri that contained the text of the Book of Abraham. In historical hindsight, however, they could not have been; the portion of papyrus identified by nineteenth-century eyewitnesses as containing the Book of Abraham seems to have gone to Wood’s Museum and was presumably burned in the Chicago Fire of 1871. There is, at present, no way of recovering it.

But of more interest than the travels and travails of the papyri is what Joseph Smith did with them.

Papyri Joseph Smith I. This is the opening vignete in the scroll belonging to Horos, son of Osoroeris. Facsimile I from the Book of Abraham is based on this illustration. This is the only element associated with the Book of Abraham that survives among the Joseph Smith Papyri.

Papyri Joseph Smith I. This is the opening vignete in the scroll belonging to Horos, son of Osoroeris. Facsimile I from the Book of Abraham is based on this illustration. This is the only element associated with the Book of Abraham that survives among the Joseph Smith Papyri.

Further Reading

History of the Papyri before their Acquisition by Joseph Smith

Curto, Silvio, and Laura Donatelli. Bernardino Drovetti Epistolario (1800–1851). Milano: Cisalpino–Goliardica, 1985. This is a collection of letters written to Bernardino Drovetti. It provides some information about some of the individuals working for Drovetti doing excavations in Egypt.

Donatelli, Laura. Lettere e Documenti de Bernardino Drovetti. Torino: Accademia delle Scienze, 2011. This volume contains more of Drovetti’s correspondence. The introduction sorts out some of the individuals that Drovetti had working for him.

Guichard, Sylvie. Lettres de Bernardino Drovetti consul de France à Alexandrie (1803–1830). Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 2003. This volume contains letters sent by Drovetti to a shipping firm in Marseilles. It contains some information about how the Joseph Smith Papyri were taken from Drovetti’s collections and sent to America.

———. “Nouvelle approche de Bernardino Drovetti, Consul de France en Égypte de 1803 à 1829, à partir d’une correspondence inédite récemment acquise par le Musée du Louvre.” In Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Egyptologists, edited by Jean-Claude Goyon and Christine Cardin, 1:871–76. Leuven: Peeters, 2007. This is the first published analysis of a new cache of letters of Bernardino Drovetti. Among the letters are those that detail how Drovetti had Lebolo send a group of Egyptian objects to America. Guichard does not recognize these objects as including the Joseph Smith Papyri.

Muhlestein, Kerry. “Prelude to the Pearl: Sweeping Events Leading to the Discovery of the Book of Abraham.” In Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church, 130–41. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004. This article examines the political situation in Egypt leading to the discovery of the Joseph Smith papyri.

Smith, Brian L. “A Book of Abraham Research Update.” In BYU Religious Studies Center Newsletter, May 1997, 5–8. This short report outlines new information about the various travels of the Joseph Smith Papyri before they were acquired by Joseph Smith.

Colonel Wood's Museum after the Chicago fire, 9 October 1871. By Lovejoy & Foster, Courtesy of New York Public Library. Wikimedia Commons.

Colonel Wood's Museum after the Chicago fire, 9 October 1871. By Lovejoy & Foster, Courtesy of New York Public Library. Wikimedia Commons.

History of the Papyri while Joseph Smith owned them

Gee, John. “Eyewitness, Hearsay, and Physical Evidence of the Joseph Smith Papyri.” In The Disciple as Witness: Essays on Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, 175–217. Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2000. Among other things, this article uses eyewitness accounts of the Joseph Smith Papyri to ascertain what state of preservation the various papyrus fragments were in at various points in time. It also discusses what became of the various papyrus fragments.

———. “New Light on the Joseph Smith Papyri.” FARMS Review 19, no. 2 (2007): 245–59. This work, originally given at an Egyptological conference, brings together a few additional sources relating to the Joseph Smith Papyri.

———. “Some Puzzles from the Joseph Smith Papyri.” FARMS Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 113–37. The first part of the article provides an overview of the history of the Joseph Smith Papyri.

Muhlestein, Kerry, and Alexander L. Baugh. “Preserving the Joseph Smith Papyri Fragments: What Can We Learn from the Paper on Which the Papyri Were Mounted?” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 66–83. This careful analysis of the backing papers upon which the Joseph Smith Papyri were mounted tells us about the process by which the papyri were mounted and enables us to date when they were mounted to 1837.

Peterson, H. Donl. The Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995. This work is invaluable for the new material it brings to supplement Jay Todd’s work. It tries to tell the story of the Joseph Smith Papyri; however, it gets confused sometimes about whether it is telling that story or the story of how Donl Peterson discovered the new information that he is providing.

Todd, Jay M. The Saga of the Book of Abraham. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1969. This classic and now hard-to-find work quotes a large number of primary sources dealing with the discovery and travels of the Joseph Smith Papyri. Although the work was groundbreaking when it came out, it is not necessarily well organized.

History of the Rediscovery of the Papyri

Gee, John. “Hugh Nibley and the Joseph Smith Papyri.” In Hugh W. Nibley, An Approach to the Book of Abraham, vol. 18 of the Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, xiii–xxxix. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2009. This essay, the introduction to Hugh Nibley’s early work on the Joseph Smith Papyri and the Book of Abraham, tells the story of how the current fragments of the Joseph Smith Papyri were given back to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and how Hugh Nibley became involved with studying them.

Notes

[1] This was the heading to the Book of Abraham as published in 1842. I have altered the capitalization and punctuation slightly.

[2] Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, vol. B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], 596.

[3] William S. West, A Few Interesting Facts Respecting the Rise, Progress, and Pretensions of the Mormons (Warren, OH: 1837), 5.

[4] Josiah Quincy, Figures of the Past from the Leaves of Old Journals (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1883), 386.

[5] Henry Caswall, The City of the Mormons; or, Three Days in Nauvoo, in 1842 (London: Rivington, 1843), 22–23.

[6] Charlotte Haven to her mother, 19 February 1843, printed in “A Girl’s Letters from Nauvoo,” Overland Monthly 16, no. 96 (December 1890): 624.

[7] Jerusha W. Blanchard, “Reminiscences of the Granddaughter of Hyrum Smith,” Relief Society Magazine 9, no. 1 (1922): 9.

[8] M., Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer, 3 October 1846, 211.

[9] Haven to her mother, 19 February 1843.

[10] Oliver Cowdery to William Frye, 22 December 1835, Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate 2 (December 1835): 234.