First Vision–Based Christology and Praxis for Anxious Teens

Steven C. Harper

Steven C. Harper, “First Vision-Based Christology and Praxis for Anxious Teens,” in How and What You Worship: Christology and Praxis in the Revelations of Joseph Smith, ed. Rachel Cope, Carter Charles, and Jordan T. Watkins (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 1‒10.

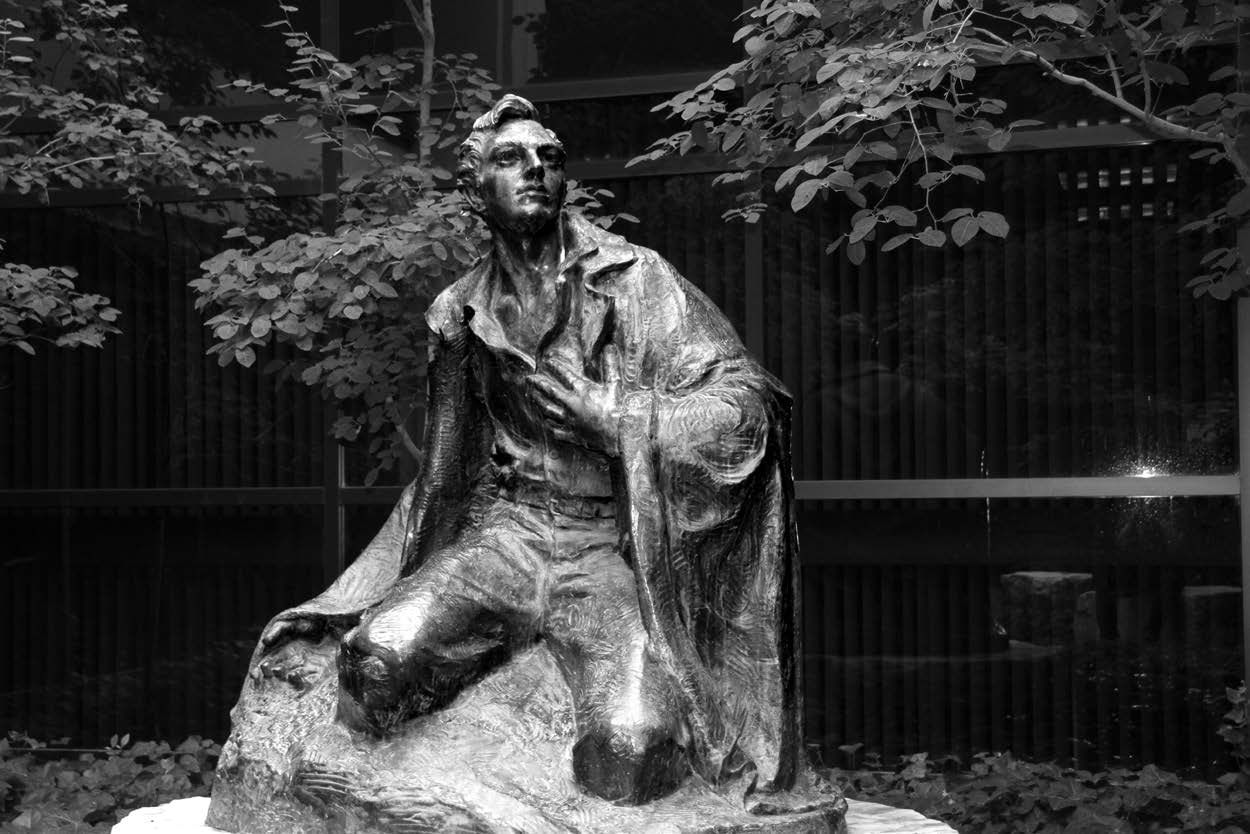

There is a sacred grove about fifty feet from my office. It is in the atrium of the Joseph Smith Building on the campus of Brigham Young University. The trees are blossoming as I write. A bronze figure of Joseph Smith is kneeling among them. He is about fourteen years old. He is looking up.

Avard T. Fairbanks’s sculpture The Vision is located in the courtyard of the Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University. When Elder Henry B. Eyring unveiled the sculpture in 1997, he paid tribute to the sculpture "for what he didn’t show," referring to the implied presence of the Father and the Son. Photo courtesy of Brent R. Nordgren.

Avard T. Fairbanks’s sculpture The Vision is located in the courtyard of the Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University. When Elder Henry B. Eyring unveiled the sculpture in 1997, he paid tribute to the sculpture "for what he didn’t show," referring to the implied presence of the Father and the Son. Photo courtesy of Brent R. Nordgren.

When Henry B. Eyring unveiled and dedicated this sculpture in 1997, he praised the artist, Avard Fairbanks, for what Joseph’s heavenward gaze invites us to imagine. President Eyring said, “From studying the various accounts of the First Vision, we learn that young Joseph went into the grove not only to learn which church he should join but also to obtain forgiveness for his sins, something he seems not to have understood how to do.”

President Eyring hopes that every young person who sees the statue will relate to Joseph in the moment depicted, “that moment when Joseph Smith learned there was a way for the power of the Atonement of Jesus Christ to be unlocked fully.” According to President Eyring, “in more than one account the Lord addressed the young truth seeker and said, ‘Joseph, my son, thy sins are forgiven thee.’”[1]

Joseph’s parents “spared no pains” in teaching him “the Christian religion.” They taught him that the scriptures “contained the word of God.” Joseph wrote that he was about twelve when he began to worry about the welfare of his immortal soul. His “all important concerns” led him to exercise faith in his parents’ teachings. He began searching the scriptures for himself and doing what he called “applying myself to them.” That is how he discovered that various Christian churches professed things the Bible did not.

Joseph grieved over that. He could see that contention characterized Christianity. He became deeply distressed because he believed the Christian teachings about his sinful and fallen state. He knew he needed to be redeemed by Jesus Christ, but “there was no society or denomination,” as far as he could tell, “that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament.” He wrote, “I felt to mourn for my own sins and for the sins of the world.”[2]

Joseph took the welfare of his soul seriously. For a few years he thought about his problem and what he should do. He considered the option of giving up his faith in God, but he could not. To him, the sun, moon, and stars testified that God lived—and lived by divine laws—and should be worshipped. “Therefore,” Joseph wrote, “I cried unto the Lord for mercy, for there was none else to whom I could go.”[3]

My focus is on Joseph’s actions as described in that last sentence and why he acted as he did. He chose a powerful verb in cried. Joseph cried to the Lord for mercy because he was losing hope. There was no one else to extend him mercy. So he cried because he believed, or at least hoped, that the Lord would be merciful to him. Scholars call it praxis when a person does something to worship the Lord, something like hoping in Christ or crying unto the Lord.

Scholars use the word Christology to describe what people believe about Jesus Christ. Who is he? What is he like? Joseph believed, or at least hoped, that Christ is merciful. Joseph’s Christology and his praxis were connected. He did what he did because of what he thought about Jesus. He cried unto the Lord for mercy because he believed the Lord alone could give him the mercy he needed.

In his revelations to Joseph, Jesus Christ tells who he is and shows what he is like. He revealed lots of beautiful Christology. He also instructed us to do (and not do) specific things. In other words, he revealed much praxis. The focus here, however, is only on Joseph’s first revelation. It is about how the teenage Joseph worshipped Jesus Christ and what he learned about him.

As President Eyring demonstrated, there is value in learning Christology and praxis from Joseph’s various accounts of his vision. They tell us what Joseph did. He believed his parents’ teachings about Jesus Christ. He searched the scriptures and believed that they contained the word of God. He applied himself to them. He worked hard to understand them and to discover what he should do because of them. He became intimately acquainted with people who believed different things about Christ and worshipped him in various ways. He paid attention to what they believed and what they did. For a few years he read, observed, and pondered. He thought about what he was becoming. He mourned when there was conflict between what he believed he should be and what he was. He became “exceedingly distressed” when he realized he was at an impasse. He was guilty of sin, and he could find no church built on the gospel of Jesus Christ who redeemed people from their sins. So he cried out to the Lord for mercy.[4]

One of the best things Joseph did was to balance urgency and caution. That is good praxis. He recognized that he needed knowledge and power from God. Learning how to get it became his priority. “Information was what I most desired,” he said, and he formed a “fixed determination to obtain it.” He said it was “of the first importance that I should be right in matters that involve eternal consequences.”[5] Joseph put first things first. He relentlessly sought the most important truths.[6] Because his “immortal soul” was at stake, he acted both urgently and deliberately.[7]

He did not make rash decisions or jump to conclusions. “I made it an object of much study and reflection,” he related.[8] “I kept myself aloof from all these parties,” he said, “though I attended their several meetings as often as occasion would permit.” By exercising faith in God, studying much, observing closely, yet remaining aloof, Joseph positioned himself to make informed decisions. He could see that “contradictory opinions and principles laid the foundation for the rise of such different sects and denominations.” Being deliberate helped Joseph remain above the partisan prejudices “too often poisoned by hate, contention, resentment and anger.”[9]

Joseph tested Methodism. “In process of time my mind became somewhat partial to the Methodist sect,” he said, “and I felt some desire to be united with them.” If the Methodist teachings were right, Joseph would be able to seek and receive God’s prevenient grace. That is, despite his fallen nature, Joseph would receive a gift of God’s power that would enable him to come to Christ and be saved by him. He would know if it worked because it would be joyful, overwhelmingly joyful. Joseph watched as people experienced that joy. He tried it himself. He wanted his own Methodist conversion experience. “He wanted to get Religion too wanted to feel & shout like the Rest but could feel nothing.”[10] So despite his desire to follow Methodist Christology, Joseph kept seeking.

He sought more evidence before concluding whether Methodism or one of the other versions of Christianity had the right doctrine of Christ. He realized that he was not able to discern by himself whether Methodists were right, or Presbyterians, or Baptists. Each made compelling, Bible-based arguments. That confused, distressed, and perplexed Joseph.[11]

What did he do in those circumstances? What was his religious praxis or practice when experts offered conflicting, consequential choices? He kept his faith. He worked hard. He turned to the scriptures. He received a revelation. Then he acted on it. “While I was laboring under the extreme difficulties caused by the contests of these parties of religionists,” he said, “I was one day reading the Epistle of James, First Chapter and fifth verse.” The scripture taught him to ask God directly and with faith. That was a revelation to Joseph, “like a light shining forth in a dark place.”[12] Before he read and reflected on it, he felt paralyzed; after, he knew what to do.

“I must do as James directs,” he said, “that is, Ask of God.” Joseph chose the word determination to describe his resolve to act on the scripture.[13] He used it twice in his history. Another time he called it “a fixed determination.”[14] Joseph’s was no passive praxis. He was going to act on the revelation he had received. He said, “I just determined I’d ask him.” Joseph unwaveringly resolved to act in faith and do something he had never tried before. He went to the woods to take the next step in his quest for God’s redeeming love.[15]

Joseph knelt and “began to offer up the desires of my heart to God.” He had never prayed aloud before.[16] It was good praxis to pray, to ask God to grant the sincere desires of one’s heart. Joseph barely got started, however, before he stopped. He called it “a fruitless attempt to pray.”[17] It felt like his tongue swelled. He could not speak. It sounded like someone was walking up behind him. He tried to pray again but failed. The noise seemed to come closer. He sprang up and turned toward it. There was nothing making the noise, nothing he could see anyway.

He knelt again and “called on the Lord in mighty prayer.”[18] Something seized him, “some power which entirely overcame me,” he said. It was an enemy, “an actual being from the unseen world.” Joseph was shocked at its power.[19] Doubts filled his mind.[20] Thick darkness enveloped him. He felt doomed. He was ready to give up, “to sink into despair and abandon myself to destruction,” he said. He chose not to do so, however. He chose instead, at that moment, to exert all his “powers to call upon God to deliver me out of the power of this enemy.”

Just then Joseph saw a brilliant light descending from above. He called it a “pillar of flame.” As soon as it appeared the darkness left. The spirit of God filled Joseph, replacing the feeling of despair. Unspeakable joy replaced doom. Joseph heard his name. He looked into the light and saw God, who introduced Joseph to his Beloved Son. Joseph saw Jesus Christ, standing in the air with his Father. “Joseph,” the Savior said, “thy sins are forgiven.” He continued, “I am the Lord of glory. I was crucified for the sins of the world that all those who believe on my name may have eternal life.”[21]

Once he could speak, Joseph asked if he should join the Methodists. “No,” came the answer.[22] None of the current Christian churches had their Christology right. They relied too much on confusing creeds. The person and work of Jesus Christ was simpler than they taught. “Jesus Christ is the son of God,” Joseph learned. He was crucified for sinners. He forgives the repentant and gives them eternal life. He can stand next to his Father, and not just in heaven. They can visit in person. They answer the prayers of anxious teenagers who ask in faith.

Joseph learned well. He put his faith in the crucified and resurrected Savior who had atoned for his sins, and he repented. Joseph knew what to do later when he realized “that I had not kept the commandments.” Every time he “fell into transgressions and sinned in many things,” he went back to his knees, chose hope over despair, and acted on the christological knowledge he had successfully tried before. He trusted the Savior who was crucified for him and “repented heartily for all my sins.”[23] That praxis worked every time.[24]

Primary General President Joy D. Jones taught, “we can draw principles of truth from the Prophet Joseph’s experiences that provide insights for receiving our own revelation.” She noted these examples of good practice: “We labor under difficulties. We turn to the scriptures to receive wisdom to act. We demonstrate our faith and trust in God. We exert our power to plead with God to help us thwart the adversary’s influence. We offer up the desires of our hearts to God. We focus on His light guiding our life choices and resting upon us when we turn to Him. We realize He knows each of us by name and has individual roles for us to fulfill.”[25] That praxis works every time.

When he unveiled the sculpture of Joseph in the grove near my office, President Eyring similarly linked Christology and praxis. Like President Jones, he based the connection on what Joseph learned in the grove. President Eyring testified, “Jesus is the Christ. He lives. I know He lives. I know Joseph Smith saw Him, and I know that because He lives and because Joseph Smith looked up and saw Him and because He sent other messengers, you and I may have the thing that the Prophet Joseph wanted as he went to the grove: to know, not just to hope, that our sins can be washed away.”[26]

Notes

[1] Henry B. Eyring, “Remarks Given at the Unveiling Ceremony of ‘The Vision,’” Religious Education History, Brigham Young University, 66–68.

[2] “History, circa Summer 1832,” pp. 1–2, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[3] “History, circa Summer 1832,” pp. 2–3.

[4] “History, circa Summer 1832,” pp. 2–3.

[5] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 23, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[6] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 23.

[7] “History, circa Summer 1832,” p. 2.

[8] “History, circa 1841, fair copy,” p. 2, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[9] “Orson Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste (A Cry out of the Wilderness), 1842, extract, English translation,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[10] “Alexander Neibaur, Journal, 24 May 1844, extract,” p. [23], The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[11] “History, circa Summer 1832,” p. 2. “History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2],” p. 3, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[12] “Appendix: Orson Pratt, A[n] Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, 1840,” p. 4, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[13] “History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2],” p. 3.

[14] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 23.

[15] “History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2],” p. 3.

[16] “History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2],” p. 3.

[17] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 23.

[18] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 24.

[19] “History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2],” p. 3. “History, circa 1841, draft [Draft 3],” p. 3.

[20] “Orson Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste (A Cry out of the Wilderness), 1842, extract, English translation.”

[21] “History, circa Summer 1832,” pp. 2–3.

[22] “Alexander Neibaur, Journal, 24 May 1844, extract,” p. [23].

[23] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 24; spelling corrected.

[24] “Journal, 1835–1836,” p. 24. “Revelation, July 1828 [D&C 3],” p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[25] President Joy D. Jones, “An Especially Noble Calling,” Ensign, May 2020, https://

[26] Eyring, “Remarks Given at the Unveiling Ceremony,” 66–68.