Taylor Halverson, “The Path of Angels: A Biblical Pattern for the Role of Angels in Physical Salvation,” in The Gospel of Jesus Christ in the Old Testament, The 38th Annual BYU Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009).

Taylor Halverson is a faculty consultant for Brigham Young University’s Center for Teaching and Learning.

Among the characters that populate the biblical landscape, angels play a particularly noteworthy, though not always fully understood, role. Because of their pervasive presence in the Restoration, we as Latter-day Saints may feel especially familiar with angels and what we see as their work: bearing testimony of Jesus Christ and his gospel. Yet I believe we can expand our understanding of the role of angels through an investigation of select Old Testament passages. What I hope to portray is a pattern of how angels are involved in the physical salvation[1]—or destruction—of individuals and groups so that God’s promises can be fulfilled and his purposes can roll forth.

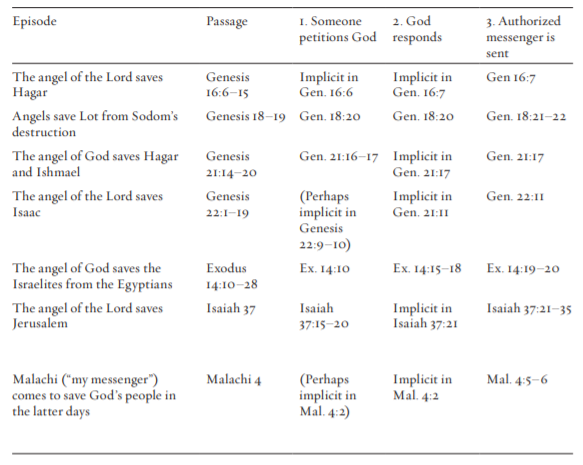

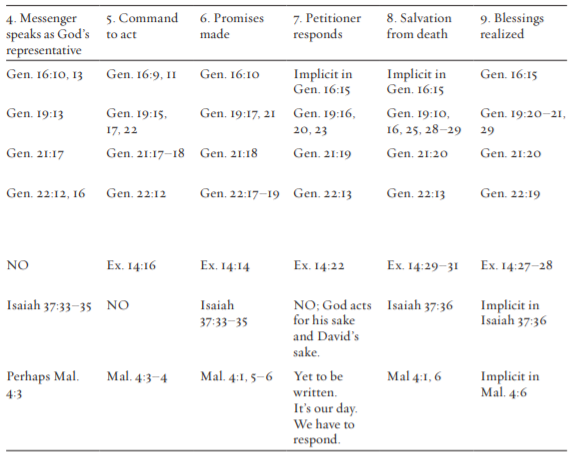

Angels’ involvement in physically saving people in order to lead them to God’s blessings typically follows the pattern presented below:[2]

- Someone petitions God (usually in distress).

- God responds (perhaps God convenes the heavenly council).

- An authorized messenger is sent (an angel or a prophet).

- The messenger speaks as God’s representative (sometimes speaking as God).[3]

- The messenger commands the petitioner to do something.

- The messenger conveys God’s promises.

- The petitioner responds to the commands.

- The messenger saves the petitioner from physical death.

- The petitioner receives or realizes blessings from God.

This chapter will first briefly review common Latter-day Saint beliefs about the roles of angels. Then I will share the underlying meanings of the scriptural Greek and Hebrew words for angel. Second, I will place angels in the context of the ancient Israelite culture, in which they belong to God’s heavenly council and serve as his authorized messengers. Fourth, I will review several significant passages in the biblical record that follow, fully or in part, the pattern expressed above—depicting angels delivering messages that save people from death. Finally, I will explain how the Old Testament depiction of angelic roles can add to our understanding of angels’ work from the history of the Restoration and the pages of restoration scripture.

Restoration Perspectives on Angels

The modern-day Restoration has acculturated us to certain views and perspectives about angels. Indeed, the Restoration was in many regards constructed revelation-by-revelation through angelic mediation. The angel Moroni instructed Joseph Smith at length on numerous occasions about the plan of God in the latter days (see D&C 2).[4] The sacred location of the Book of Mormon would have remained quietly concealed without Moroni’s revelatory disclosure.[5] Other angels heralded the restoration of priesthood keys. Peter, James, and John restored the Melchizedek Priesthood (see D&C 128:20), and John the Baptist the Aaronic Priesthood (see D&C 13).[6] Other angels, including Moses, Elijah, and Elias, appeared to Joseph Smith over time, each to deliver keys and knowledge necessary for the building of God’s kingdom (see D&C 110).

The Book of Mormon narrative influences us to feel especially familiar with the role and purpose of angels.[7] We hear of angels visiting both Jacob (see 2 Nephi 9:3) and King Benjamin (see Mosiah 3:1–3) with heavenly testimony of the gospel and Jesus Christ. Or we might think of the angel who visited Alma the Younger at various stages in his life. As a rebellious youth, Alma was struck dumb by the thunderous voice of an angel (see Mosiah 27:11–12). Yet in later righteous years, that same angelic voice penetrated Alma’s heart with words of blessing (see Alma 8:14–17). These few episodes from the Book of Mormon underscore our perspective that angels convey the word of God to mankind. In this regard, the passage that “angels speak by the power of the Holy Ghost; wherefore, they speak the words of Christ” (2 Nephi 32:3) dominates the LDS perspective on the function of angels.

Thus Restoration scripture has given us the understanding that angels testify of the gospel and of Jesus Christ, share priesthood keys and powers to further the work of God, and deliver God’s promises to the faithful. This study proposes, through an investigation of select Old Testament texts, to expand our perspective of the role of angels to allow us to see that angels were also authorized by God to physically save or destroy individuals or groups so that God’s promises and purposes could be realized.

“Angels”—Definitions from Two Languages

The English word angel derives from the Greek aggelos, which means “messenger.”[8] Aggelos is based on the root verb aggello, which means “to tell, to inform.”[9] These definitions suggest that the basic role of an aggelos is to deliver a message.

As helpful as these Greek definitions are (especially since we can readily see the linguistic connection between the English angel and the Greek aggelos), the Old Testament was not written in Greek, but rather in Hebrew.[10] So what is the underlying Hebrew word for our English translation of angel? Mal’ach.[11] The basic definition of the agent noun mal’ach is “one who is sent forth,” usually with a message.[12] As we saw with the Greek definition of aggelos, the term mal’ach is sufficiently straightforward to declare the primary function of an angel—one who goes forth with a message.

We should highlight that the Greek aggelos and the Hebrew mal’ach make no distinction between heavenly or earthly messengers. The Old Testament refers to God’s authorized messengers as mal’achim whether they are of heavenly origin (which in our day we consider to be angels) or of earthly origin (some Old Testament prophets fill the role).[13] It wasn’t until Jerome’s late fourth century AD Latin translation of the Bible (the Vulgate) that an attempt was made to distinguish between heavenly messengers (Latin angelus) and earthly messengers (Latin nuntius).[14]

In this study, I confine my investigation to deal only with passages where a mal’ach is part of the story. Hence, I do not consider cherubim, seraphim, sons of God, or holy ones as angels, because, from a linguistic standpoint, none of them is a mal’ach, or messenger. With this rather pedestrian understanding of the meaning of the word angel—a messenger—what message do these messengers convey? Who sends them on their errand? And for what purpose?

Angels in God’s Heavenly Council

Ancient Israelites believed that God resided in heaven, surrounded by his heavenly council.[15] Just as a royal court consists of different members with different roles and purposes (e.g., counselor, messenger, jester, warrior, or bodyguard), so too God’s heavenly court was composed of a variety of heavenly beings. According to the Old Testament, God’s heavenly council consisted of beings such as the sons of God (see Psalms 89:7; Job 38:7), gods (see Psalm 58:1[16]; 82:1[17]; 97:7; 138.1), the stars (see Job 38:7), members of the council of God (see Job 15:8), members of the assembly of holy ones (see Psalm 89:5–6[18]; Job 5:1[19]), ministers (see Psalm 103:21), prophets (see Amos 3:7), and angels.[20]

Angels participated in the heavenly council as plenipotentiary messengers. Their role included serving as mediators, guardians, servants to beings of higher rank in the council (called “gods” in Psalms),[21] and spokespersons for the council. Angels depicted in the Old Testament primarily served the great Master of the court, Jehovah; they acted in his name, conveyed his messages, and did his will to bring either physical salvation or physical destruction to people, being commissioned in the council to do so.

According to some ancient texts,[22] God’s heavenly council functioned in the following way: God assembled the members of his council whenever there was an issue to discuss and a decision to be made. Next, God carefully listened to the various proposals and then rendered a decision. It was at this point that an angel (or a prophet)[23] who had participated in the heavenly council was commissioned to go forth from the heavenly council in God’s name and share on earth whatever had been decreed in heaven, whether unto physical salvation or death.[24]

A rare but valuable scriptural description of God’s heavenly council is found in 1 Kings 22 (see especially verses 19–23). In this chapter, wicked king Ahab contemplates going to war against his enemies. Ahab gathers together his hundreds of prophets, who all predict success. However, these prophets are afflicted with a lying spirit—they say whatever the king wants to hear. Another prophet, Micaiah, who has been commissioned of the Lord, comes to the royal court and describes that he has participated in God’s heavenly council. Micaiah risks his life by sharing the message decreed in God’s heavenly council of Ahab’s physical destruction: Ahab would die in battle. Sure enough, Ahab dismisses Micaiah’s warning, goes forth to battle (in disguise), and is killed by an errant arrow (see 1 Kings 22:34–38).

Angels as Agents of Physical Salvation or Destruction in the Old Testament

With these angelic perspectives and definitions, we will now examine seven Old Testament stories that display or at least play on the pattern presented above, highlighting the crucial role angels perform to physically protect someone so that God’s promises might be fulfilled or, on the other hand, to destroy people who threaten God’s purposes.

The angel of the Lord saves Hagar (see Genesis 16).

Then Sarai dealt harshly with [Hagar], and she ran away from her.

The angel of the Lord found her by a spring of water in the wilderness. . . .

And he said, “Hagar, slave-girl of Sarai, where have you come from and where are you going?”

She said, “I am running away from my mistress Sarai.”

The angel of the Lord said to her, “Return to your mistress, and submit to her.”

The angel of the Lord also said to her, “I will so greatly multiply your offspring that they cannot be counted for multitude.”

And the angel of the Lord said to her, “Now you have conceived and shall bear a son; you shall call him Ishmael, for the Lord has given heed to your affliction. . . .

So she named the Lord who spoke to her, “You are El-roi”; for she said, “Have I really seen God and remained alive after seeing him?” (New Revised Standard Version, Genesis 16:6–11, 13)

This passage represents the first biblical appearance of an angel. In studying how well it stacks up against the proposed pattern of angelic intervention, we find that it contains, implicitly or explicitly, all nine features of the pattern. First, Hagar is in distress, though no explicit petition to the Lord is cited. Nevertheless, God responds to her grievance by sending forth a messenger who speaks authoritatively for him. Following a short interrogation as to why Hagar fled, the angel commands her to return and submit to Sarah. Then the angel pronounces the stunning promise, “I will so greatly multiply your offspring that they cannot be counted for multitude” (v. 10).

The angel’s appearance and blessing evoke two surprises, one for us and one for Hagar. Most of us are familiar with the language of blessing as it pertains to the Abrahamic promise, but we may be surprised to hear that Hagar receives the same promise of a multitude of offspring as Abraham. Upon further reflection, we see this connection as entirely logical and necessary—those who bear Abraham’s seed have the same promises extended to them of countless multitudes of descendants. Without Sarah,[25] Hagar, and Keturah, the promises so often associated with Abraham can never be realized. As if to underscore the future reality of Hagar’s multitudinous offspring, the angel announces that Hagar is pregnant with a child who shall be named Ishmael (“God hears”), a name fitting to memorialize God’s hearing her in her afflictions.

The other surprise is for Hagar. So thoroughly does this angel represent the Lord, that Hagar mistakenly believes she has seen God.[26] After the angel leaves, Hagar questions, “Have I really seen God and remained alive after seeing him?” (v. 13). Notice that Hagar is surprised that she is still alive. The common conception in Old Testament times was that no one could see the face of God and live; at the very least, anyone who did come into the presence of God would have felt the vast difference between the overwhelming holiness of the Lord and his or her own thorough uncleanliness (compare Isaiah in his theophany recorded in Isaiah 6:1–6). What we are to conclude from her statement is that so fully does the angel authoritatively represent the Lord that Hagar believes that she has encountered the Lord himself.

The conclusion of this episode is that the angel saves the life of Hagar and, by extension, the lives of all members of Abraham’s posterity descended through her. Had Hagar not obeyed the command to return to the tent of Abraham and submit to the hand of Sarah, she likely would have famished in the wilderness. The angel’s message and Hagar’s adherence to that message are the means of Hagar’s personal, physical preservation. Her obedience helps realize God’s mighty promises. Had she failed to heed the angel’s admonition to be humble, she never would have realized (in the fullest sense) the promised blessings.

Angels save Lot from Sodom’s destruction (see Genesis 18–19). The next instance of angelic intervention occurs in Genesis 18–19. Three men visit Abraham in Genesis 18 to reiterate the promise that he will inherit a large posterity.[27] Due to ambiguities in the text, it seems that the three men are the Lord and two angels. As the narrative progresses, the Lord stops to counsel with Abraham concerning the impending destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (see vv. 17–33). Meanwhile, the men who have come to visit Abraham continue their journey (see v. 22) to Sodom and Gomorrah as messengers of physical salvation and destruction for the inhabitants of the cities. Those who heed the messengers’ warning (Lot and his family) are temporally saved, while those who reject the messengers are duly destroyed. Similar to Hagar’s story, the evidence is clear that angels play a significant part in the physical salvation of God’s chosen people.

This episode fulfills all nine elements of angelic intervention. In Genesis 18 there is an outcry to God because of the wickedness at Sodom and Gomorrah (see v. 20). God responds by sending angels[28] to Sodom (see vv. 20–22), who say that the Lord has sent them to destroy the city (see Genesis 19:13).[29] However, in Genesis 19 when the angels command Lot to take his family and get out of town (see v. 15), Lot lingers.[30] When the angels see Lot lingering, they physically drag him and his family out of the city. This is the second time in as many days that the angels have to touch Lot to literally save him (they had dragged him into his house the night before to save him from the angry mob; see vv. 9–11).

In most instances, someone is saved not because an angel reaches out and touches them, but rather because they respond in faith to the commands of God. And by so responding to God, they remove themselves from harm’s way or return to an environment of protection. The analogy here is that God calls us to “come unto him” (Alma 5:34–36) but will not force us into his arms (see Mormon 6:17). However, in Lot’s circumstance, the situation is apparently sufficiently dire and his response sufficiently tardy that the angels pull him out of danger. This is physical salvation at its best.

The pattern of angelic involvement continues. The angels command Lot to escape to Zoar and not look back (see vv. 15, 17, 22), promising him safety there (see v. 21). Finally, Lot heeds the message, flees to Zoar, and secures the blessing of life (see vv. 21, 29).

In summary, what we learn from Lot’s story is that God will send forth his angels to warn. Those who heed the warnings achieve physical safety and see the blessings of God realized in their lives, even if it is the most basic (and yet the most precious) of all God’s blessings—life itself. On the other hand, those who do not heed the message of God’s messengers are wiped out, such as Lot’s sons-in-law, the wicked inhabitants of Sodom, and even Lot’s wife, who at first heeds the angelic message but then turns and rejects it to her own salty demise.

The angel of God saves Hagar and Ishmael (see Genesis 21). Some years after Hagar’s first encounter with an angel, she once again faces death in a trackless wilderness because of conflict with Sarah. Sarah does not want Hagar’s son Ishmael to receive the family inheritance (see v. 10), so she requires Abraham to thrust Hagar out to secure Isaac’s position as the child of the promise (see v. 10). Abraham reluctantly sends Hagar on her way only after the Lord tells Abraham to hearken to the voice of his wife (see v. 12).

After wandering for some time in the desert until her food and water are spent, Hagar casts Ishmael under a bush (see v. 15) while she sits a ways off not wanting to see him die. In this dire situation, God hears the boy crying. He sends an angel to call out to Hagar from heaven to reclaim the boy, reminding her of his original promise that Ishmael would be a great nation (see vv. 17–18). God opens her eyes and she sees a well of water that quenches their thirst and saves them from death (v. 19).

This episode fulfills all the elements of the pattern; the angel speaks for God (see v. 17), renews God’s promises to Hagar, and delivers a message that requires action on her part to secure physical salvation for herself and her son (see v. 18). When her eyes are opened to see the well of water, she goes forth to drink and shares with her son to stave off his death in the desert (see v. 19). The reward for responding faithfully to God’s angel-delivered message was immediate salvation from physical death (see v. 19) and the eventual fulfillment of Ishmael’s portion of the Hagar-Abrahamic promises: “And God was with the lad” (v. 20). Just as we see in the first passage of angelic intervention in Hagar’s life, had she not listened and responded to the angel, she would have died in the desert with Ishmael and thus forfeited the grand promises as coheir with Abraham.

The angel of the Lord saves Isaac (see Genesis 22). The Akedah story, also known as “the Binding of Isaac” or “the Sacrifice of Isaac,” is one of the most memorable stories in scripture. It provides both a foundation for discussing the principles of faith, obedience, and sacrifice and a foreshadowing of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. With remarkable reticence, the nearly tragic story is told with minimal detail and in a vacuum of emotion. These narrative features heighten the intensity of the near-death drama when Abraham’s hand is raised to strike his son with the fatal blow of sacrificial slaughter (see v. 10). Just when the unimaginable is about to happen, and in what appears to be a last-second voice of salvation, an angel of the Lord calls out from heaven to Abraham, “Lay not thine hand upon the lad” (v. 12). Abraham hearkens to the voice of God’s messenger, the crisis is averted, and the victory of faith is assured (see v. 13).

Because of Abraham’s unswerving righteousness in an enormously difficult spiritual test replete with the traumatic horrors of memories past,[31] the angel of the Lord calls out to Abraham a second time with promises as great as the stars of heaven: “By myself have I sworn, saith the Lord, for because thou hast done this thing, and hast not withheld thy son, thine only son: That in blessing I will bless thee, and in multiplying I will multiply thy seed as the stars of the heaven, and as the sand which is upon the sea shore; and thy seed shall possess the gate of his enemies; And in thy seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed; because thou hast obeyed my voice” (Genesis 22:16–18).

In this episode, God sends forth an angel, who gives a command speaking as God; Abraham dutifully obeys; and Isaac’s physical salvation is secured (see vv. 11–13). God’s promises to Abraham are renewed (see vv. 16–18) and can now be fulfilled because Isaac has survived.[32]

The notable observation that this pattern points out to us is that the angel of the Lord is the agent who physically saves the righteous, so long as they hearken to his message. Those who heed God’s voice will receive the magnanimous blessings promised by the messenger. We also see that God tests the faithful to the very limits of physical existence. He then reaches out to save them through his commissioned angels. Finally, he grants blessings of an eternal nature to those who accept physical salvation.

The angel of God saves the Israelites from the Egyptians (see Exodus 14). The biblical episodes reviewed so far have centered on the physical salvation of a specific individual (Hagar, Ishmael, Isaac) or a small group (Lot and his family) and the blessings promised to, or secured for, them for faithfully hearkening to the voice of an angel. In this next passage, a version of the pattern appears, but this time the beneficiary is the entire host of Israel, while Moses and the angel of the Lord share the responsibility of being the Lord’s messenger.

In Exodus 14, the Israelites are fleeing the Egyptian army. Finding themselves hemmed in between the sea and Pharaoh’s deadly fighting force, the Israelites cry out to the Lord in complaint against Moses, believing that he has led them into a death trap (see vv. 10–11). However, instead of death, the Israelites find physical salvation through the mediation of the angel of the Lord: “And the angel of God, which went before the camp of Israel, removed and went behind them; and the pillar of the cloud went from before their face, and stood behind them: And it came between the camp of the Egyptians and the camp of Israel; and it was a cloud and darkness to them, but it gave light by night to these: so that the one came not near the other all the night” (Exodus 14:19–20).

The angel of the Lord stands between the Egyptian armies and the Israelites, casting darkness upon the former and bringing light to the latter. The Israelites are protected throughout the night from the onslaught of the Egyptian army. The next day, Moses stretches his hand out over the sea, and the Israelites pass through unmolested, while the pursuing Egyptians, to the very last, are sunk in the depths of the sea (see Exodus 14:21–31). So concludes what is likely the foundational moment of Israelite identity. God’s promises to Abraham of posterity and property[33] would have been entirely overthrown had the angel not physically protected the Lord’s people from the advancing Egyptians.

What is slightly different in this angelic episode from the others we have reviewed is that the Israelites are physically tested to the limits and then asked to hearken to the words of Moses and not of a mal’ach, or angel (see v. 16). God commands Moses to tell the people to move forward (see vv. 15–16), which provides the opportunity for the people to demonstrate faith in God’s word and claim physical salvation and, by extension, the promises to Abraham’s posterity. Although Moses is not explicitly called a mal’ach in this story, he plays the role of a mal’ach, an angel, a divinely authorized messenger who comes in a time of crisis, bearing a message from God that, if acted upon, will lead to physical salvation.

The angel of the Lord saves Jerusalem (see Isaiah 37). The next example we will consider comes from the time of the prophet Isaiah and the righteous king Hezekiah of Judah (circa 701 bc). The narrative is repeated in both Isaiah 37 and 2 Kings 19.[34] The historical context is that the mighty Assyrian army has advanced against Jerusalem with more than 185,000 troops to subject Hezekiah’s kingdom to paying tribute. The point is forcefully clear: Jerusalem faces imminent destruction. Up against this fearsome army and with surrender appearing to be the only option for physical deliverance, Hezekiah bows in fervent prayer (see vv. 15–20). Hezekiah pleads that God might save his people and use that victory so that “all the kingdoms of the earth may know that thou art the Lord” (v. 20).

In response to Hezekiah’s prayer, the prophet Isaiah delivers a message as the mouth of God, playing the role of an angel as God’s emissary, much like Moses had done during the Exodus: “Then Isaiah the son of Amoz sent unto Hezekiah, saying, Thus saith the Lord God of Israel, Whereas thou hast prayed to me against Sennacherib king of Assyria . . . , He shall not come into this city, nor shoot an arrow there, nor come before it with shields, nor cast a bank against it. By the way that he came, by the same shall he return, and shall not come into this city, saith the Lord. For I will defend this city to save it for mine own sake, and for my servant David’s sake” (Isaiah 37:21, 33–35). True to his promises, God sends an angel that very night to destroy the Assyrian army: “Then the angel of the Lord went forth, and smote in the camp of the Assyrians a hundred and fourscore and five thousand: and when they arose early in the morning, behold, they were all dead corpses” (Isaiah 37:36).

This episode has some interesting connections to and variants from the pattern we have seen so far. Similar to some of the other angelic stories, God’s faithful people call out to him in their distress (see vv. 15–20). He responds to them verbally through his appointed messenger (see vv. 21–35). As in the Exodus story, a prophet plays the role of the appointed messenger conveying God’s message. Still, it is the angel of the Lord (or God himself in the Exodus story) that brings the physical ruin of the enemy army (see v. 36). Promises from God are declared (see vv. 33–35), and the people are physically saved (see v. 36). What is significantly different in this passage is that neither Hezekiah nor the people are required to act on any of God’s words to partake of physical salvation. In previous examples, an individual (Hagar, Lot) or a group (the children of Israel) have had to act and follow through with a command from God’s messenger in order to realize the physical salvation made possible by the words and deeds of the angel. But in this case, God declares that he will defend Jerusalem for his own sake and for the sake of promises to one individual, King David. As the scripture records, God does defend Jerusalem. Physical salvation comes at the hands of the angel of the Lord who goes through the camp of the Assyrians destroying everyone but the Assyrian king and a few others who escape to tell the tale.

Malachi (my messenger) comes again to save God’s people (see Malachi 4). This study concludes with one final example that demonstrates how important angels are in physically saving God’s people. Significantly, this example also links us as readers to the pattern of angels’ role in physical salvation demonstrated in other biblical passages. The prophetic book of Malachi (especially chapter 4)[35] holds prominence in Latter-day Saint thought and theology because Christ quoted it to the Nephites (see 3 Nephi 25), the angel Moroni employed it as a textbook to train Joseph Smith on the Restoration, and we understand the latter days in part through the lens of these passages.

Significant to the overall discussion presented in this study is the fact that the name Malachi may not even be the real name of the prophet, but rather his title. As can readily be seen, the name Malachi is directly related to the Hebrew word mal’ach (messenger, angel). Malachi means “my messenger” or “my angel.” What more appropriate title could there be for a prophetic book that speaks of God calling out to his people in the last days to heed his messengers and be saved (first physically and then spiritually)?

Let us take a moment to see how well Malachi 4 matches the pattern of angelic intervention that has guided us so far:

For, behold, the day cometh, that shall burn as an oven; and all the proud, yea, and all that do wickedly, shall be stubble: and the day that cometh shall burn them up, saith the Lord of hosts, that it shall leave them neither root nor branch.

But unto you that fear my name shall the Sun of righteousness arise with healing in his wings; and ye shall go forth, and grow up as calves of the stall.

And ye shall tread down the wicked; for they shall be ashes under the soles of your feet in the day that I shall do this, saith the Lord of hosts.

Remember ye the law of Moses my servant, which I commanded unto him in Horeb for all Israel, with the statutes and judgments.

Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord:

And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse. (Malachi 4:1–6)

Although this is no explicit petition to God of distress, it may be implicit in verse 2. God’s response may be contained in the sending of two authorized messengers: Moses in verse 4 and Elijah in verses 5–6. Both of these messengers of God are important to the salvation of God’s people in the final days. Those who heed God’s command to remember the law of Moses (see v. 3) will be prepared to accept the message of Elijah (see vv. 5–6), thus avoiding physical death at the burning destruction awaiting the wicked who reject God (see vv. 1, 5–6).

What makes this example so important is that we in the present day are brought into the Old Testament narrative and into the pattern of angelic intervention. Significantly, two elements in the pattern (“The petitioner responds to the commands” and “the messenger saves the petitioner from physical death”) are not found directly in the scripture; they are awaiting fulfillment from us. It is now time for the people of the latter days to respond to God’s heavenly council and realize the blessings he has in store for the faithful. Just as the faithful in the Old Testament realize physical salvation if they heed the words of angels, so too do people in the latter days find physical deliverance from the burning oven on the “great and dreadful day of the Lord” if they respond faithfully to God’s messengers (see v. 3).

Concluding Thoughts on the Role of Angels in the Old Testament

Although a thorough investigation of every Old Testament passage referencing angels is not possible here, a definite pattern emerges from the passages presented. Angels are the Lord’s divinely commissioned messengers, authorized to speak the will of the Lord in response to human crisis. They provide people an opportunity to faithfully respond to God’s message and thereby be saved from some physical calamity. The passages we have reviewed are stories of God’s chosen people, encountering moments of crisis where life is threatened. Their faithful response to God’s urgent angelic messengers has meant the difference between life and death. Their faithful response has also meant the difference between their claiming or forfeiting, for themselves and their descendants, God’s Abrahamic promises; for who can claim the promises of property and posterity if death closes in before either is achieved?

Finally, it is important to connect the work of angels in the Old Testament to angelic work throughout the scriptures. Though the pattern of angelic intervention in the Old Testament appears to focus heavily on saving people from physical calamity, compared to Restoration scriptures where angels openly preach the gospel and testify of Jesus Christ, the evidence presented here has also strongly demonstrated that physical salvation is first and foremost necessary for claiming spiritual salvation. Alma clearly and succinctly teaches this truth: “And we see that death comes upon mankind, yea, the death which has been spoken of by Amulek, which is the temporal death; nevertheless there was a space granted unto man in which he might repent; therefore this life became a probationary state; a time to prepare to meet God; a time to prepare for that endless state which has been spoken of by us, which is after the resurrection of the dead” (Alma 12:24).

Those moments of crisis in the Old Testament provide God’s people an opportunity to be tested, to choose life or death (in quite a literal sense). Those who physically survive these crises because they faithfully respond to God’s authorized messengers can then lay claim to far greater spiritual promises from God.

Notes

[1] Please note that my use of “physical salvation” in this paper can also be understood as “temporal salvation.” Furthermore, my use of the terms “physical salvation” and “physical destruction” do not necessarily connote bodily contact between angels and humans.

[2] See the matrix display of this pattern set against the seven Old Testament passages discussed in this study (p. 168–69).

[3] The doctrine of divine investiture of authority can help us to understand how and why angels or prophets speak as God. The doctrine of divine investiture of authority, in its simplest expression, means that God’s representative (whether Jesus Christ, an angel, or a prophet) speaks as though God himself were present. So fully do they represent God that it is not always possible to ascertain whether God or his representative is present (James E. Talmage, Articles of Faith [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981], 424).

[4] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980), 1:9–16.

[5] Smith, History of the Church, 1:11–13.

[6] Smith, History of the Church, 1:39–41.

[7] For an accessible and thoughtful summary of the role of angels in the Book of Mormon, see Mary Jane Woodger, “The Restoration of the Doctrine of Angels as Found in the Book of Mormon,” in The Book of Mormon: The Foundation of Our Faith, ed. Joseph F. McConkie and others (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1999), 257–70.

[8] J. P. Louw and E. A. Nida, eds., Louw-Nida Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains, 2nd ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1988), s.v. “aggelos.”

[9] Louw and Nida, Greek-English Lexicon, s.v. “aggello.”

[10] More precisely, the Old Testament was written in Hebrew, with a few sections written in Aramaic: Genesis 31:47 (just two words); Ezra 4:8–68 and 7:12–26; Jeremiah 10:11; and Daniel 2:4–7:28.

[11] Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles Briggs, eds., Hebrew-Aramaic and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1996), s.v. “mal’ach.” Please note that mal’ach is not related to the Hebrew malak/

[12] Though the Hebrew root word l’k (“to send”) does not appear in the Old Testament, it does exist in other Semitic languages related to Hebrew (such as Ugaritic). We can feel fairly confident that the root word either existed in ancient Hebrew or that the ancient Israelites borrowed the word from their surrounding Semitic environment.

[13] In Greek translations of the Old Testament, such as the Septuagint, the Hebrew mal’ach is often translated as the Greek aggelos.

[14] David Noel Freedman, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), s.v. “Angels (Old Testament).”

[15] For a lengthy description of the divine council in Ugaritic and Hebrew literature, see E. Theodore Mullen Jr., The Divine Council in Canaanite and Early Hebrew Literature (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1980).

[16] The Hebrew word ’elim (gods) is translated in the King James Version (KJV) as “congregation.”

[17] The Hebrew word ’el, which means God, is translated in the KJV as “mighty,” hence it could also read “congregation of God.”

[18] The Hebrew word k’doshim (holy ones) is translated in the KJV as saints in this passage.

[19] The Hebrew word “holy ones” underlies the KJV as saints in this passage as well.

[20] Over the centuries the concept of angel was erroneously applied to all beings who resided in God’s heavenly court, even though, from a technical standpoint, these other beings were not angels. That being the case, the Old Testament passages analyzed in this study do not include passages that refer to “sons of God,” “holy ones,” or “ministers,” because these heavenly beings are not technically angels.

[21] Sang Youl Cho, Lesser Deities in the Ugaritic Texts and the Hebrew Bible: A Comparative Study of Their Nature and Roles (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2007), 137.

[22] Examples of ancient texts that portray the heavenly council are the Old Babylonian Enuma Elish, the Ugaritic Kirta epic, and Psalm 89:6–9. For a concise summary of the heavenly council in ancient thought, see Freedman, Anchor Bible Dictionary, s.v. “Divine Assembly.”

[23] The heavenly council is sometimes called in Hebrew sod (“council, assembly, secret counsel”). Therefore, the well-known passage in Amos 3:7, “Surely the Lord God will do nothing, but he revealeth his secret unto his servants the prophets,” envisions a scenario where a prophet participates in the heavenly council (Hebrew sod) and then is commissioned to share (or reveal) the council’s decision.

[24] See especially the discussion in the section “The Messenger of the Council and the Prophet” in Mullen, The Divine Council in Canaanite and Early Hebrew Literature, 209–26, where Mullen provides substantial evidence that God’s messengers, whether angels or prophets, stand in the heavenly council, hear God’s pronouncements, and then are sent forth with authority to share the divine pronouncement in the name of God.

[25] In addition to blessing Hagar and Abraham, God also blessed Sarah in a revelation to Abraham: “I will bless her, and she shall be a mother of nations; kings of people shall be of her” (Genesis 17:16).

[26] Admittedly, the biblical text is a bit ambiguous about who exactly Hagar is communicating with (we see a similar vagueness in Genesis 18 and 19). The text indicates that the angel of the Lord communicated with Hagar (see Genesis 16:9–11), and yet the angel of the Lord speaks as though the Lord himself is speaking: “I will multiply thy seed exceedingly” (Genesis 16:10). We see a similar situation of textual ambiguity in 2 Kings 18:17–37 in the story of the Assyrian Rabshakeh who is sent to convince Hezekiah through parley to submit to the Assyrian emperor. Rabshakeh (literally “cup-bearer”) was the plenipotentiary representative of the Assyrian emperor. As he attempts to convince Hezekiah to submit to Assyria, Rabshakeh slips in and out of speaking in the first person, on behalf of his master, and speaking in the first person on behalf of himself. When we read this story, it is clear that the Assyrian emperor is not personally present, even though his representative is speaking as though he were. So too in the stories of the angel of the Lord, the Lord himself is not personally present, but is fully, authentically, and authoritatively represented by his divinely chosen messenger.

[27] In interesting contrast with Hagar’s reception of God’s promises through angelic intermediation, God communicated promises to Abraham directly, without the medium of an intermediary—by direct verbal encounter (see Genesis 12 and 13), through a lucid vision (see Genesis 15), and by a personal visitation (see Genesis 17). Not until Genesis 18 does God involve other heavenly beings to convey his promises to Abraham.

[28] According to Joseph Smith Translation, Genesis 19:1, three angels arrive in Sodom. We cannot be entirely certain who the three angels are, though it is reasonable to suppose that they are the three men who visited Abraham in Genesis 18. Elder Bruce R. McConkie taught that these three angels were the First Presidency of that day (Doctrinal New Testament Commentary [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965–73], 3:235).

[29] Though both cities were marked for destruction, the angels visited only Sodom because only in that city were there any righteous to be saved (Lot and his family).

[30] As an instructive comparison, think of how the Book of Mormon story might have been different, or nonexistent, had Lehi lingered in Jerusalem!

[31] As a young man Abraham himself had been bound to an altar of sacrifice because of his father (Terah). It was only by a last-minute intervention of divine proportions that Abraham was delivered from a gruesome death on the altar of priestcraft. Just as in the story of Isaac’s deliverance from the altar, it was an angel of the Lord who saved Abraham from physical death and then made promises to him of greatness, priesthood, and posterity (see Abraham 1:1–20).

[32] It may be that Isaac, Abraham, and Sarah were all silently pleading to God that Isaac would be saved.

[33] In the Old Testament, God’s promises to Abraham of property and posterity are primarily found in Genesis 12, 13, 15, 17, and 22.

[34] For the sake of simplicity, I will work just with the Isaiah 37 text and not address the authorial and text-critical issues of comparing these two accounts.

[35] In our KJV Bibles, Malachi is the final book of the Old Testament. However, in the Hebrew Bible, the final book of the Old Testament is Chronicles.