Clinton D. Christensen, "Senior Missionaries in the Caribbean: Opening the Islands of the Sea, 1978–90," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 425–44.

Clinton D. Christensen was an archivist for the Library Division of the Church History Department when this book was published.

Richard L. Millett, president of the Florida Fort Lauderdale Mission, had just flown to Puerto Rico in the airplane of his counselor Frank Talley. A few minutes before noon on June 9, 1978, the phone rang at Talley’s home. Calling was Elder M. Russell Ballard of the Seventy. Millett later wrote in his journal, “He told us that ‘he had some news of earth-shaking consequences for our mission. . . . Tears came to my eyes and I chilled all over, as he told me that the prophet had spent days in the Upper Room of the Temple praying and supplicating the Lord. As a result, his prayers had been answered and . . . ‘the long-promised day had come when every faithful, worthy man of the Church might receive the Holy Priesthood . . . and enjoy . . . the blessings of the temple.’” [1] The phrase “earth-shaking consequences” describes perfectly how the revelation affected those of African heritage, especially in the Caribbean. When President Millett awoke the following morning, his mission boundaries had expanded tenfold to include all the islands of the Caribbean and the thirty million people residing thereon.

This paper discusses the role senior couples, mission presidents’ counselors, and native members played in introducing the Church in the Caribbean through media, health and humanitarian projects, and dedicated service missions. These efforts combined to open doors for establishing the Church in several Caribbean countries. The first portion of this paper details the very successful efforts of senior missionaries Jack and Ada Davis in the Dominican Republic. The health fair projects of President Richard Millett’s counselor Frank Talley, and his wife, Arline, will next be discussed, as well as how teaching health and hygiene principles brought the Church positive exposure and introduced it in many nations. The second part of this paper will explore the political challenges the Church faced in beginning in Jamaica, negative media efforts that disrupted the Church in Grenada and Trinidad in the late 1980s, and the role that Trinidadian Kelvin Díaz and the service of senior missionaries played in counteracting these negative influences.

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic stands as a stronghold in the Caribbean with an LDS population of over 114,000 in 2010, which is incredible growth in just over thirty years. [2] Until recently, the Dominican Republic held the record in the international Church for taking a mere twenty-two years from the entrance of the first missionaries to the completion of a dedicated temple. Several factors enabled the Church’s incredibly rapid growth. [3]

The field became white and ready to harvest in the Dominican Republic through television. Around 1974, four years before the 1978 revelation, Walter Canals, vice president of Bonneville International, oversaw the placement of the Church’s Homefront commercials that taught family values. Brother Canals met a TV manager from the Dominican Republic who loved the television spots and began showing them on his station. [4]

Four years later, in the summer of 1978, two active LDS families—the Rappleyes and Amparos—had moved to the Dominican Republic. When John Rappleye moved into his apartment, he plugged in the TV and had the following experience: “The thirty-minute Batman series was just starting. Batman was speaking Spanish. . . . Then all of a sudden they went to a commercial break and they played one of the Church family advertisements. . . . During the thirty-minute program, they played the family spots five times! We would learn that it was the same on the other channels and on radio as well. One of the stations had apparently obtained one of the ads from Bonneville Productions years earlier, and everyone loved it. It had turned into a competition between the stations to see who could get the new ads first when they came out.” [5]

When the first ten missionaries arrived in the country in November 1978 from Puerto Rico, they witnessed how the Church’s commercials had prepared the way for their proselytizing efforts. A local newspaper ran an article about the arrival of the young elders. Upon a visit from the missionaries to the newspaper office, the staff brought out letters they had received in recent years. The elders were “shown letters to the editor of the Santo Domingo newspaper which asked: “Where is this wonderful church with the great commercial messages?” The Dominicans’ interest had been piqued by the commercials. Consequently, the missionaries’ door approach was to introduce themselves as the Church with the family commercials. John Rappleye recalled that after the news story their phone rang off the hook with interested people calling, and two elders stayed by the phones constantly. [6]

An important ecclesiastical step to founding the Church in the Dominican Republic came shortly after the first missionaries arrived. Elder Ballard journeyed to the Dominican Republic under the direction of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to offer a dedicatory prayer on the land. By December 1978 several factors were in place for the successful foundation of the Church in the Dominican Republic. As previously mentioned, the commercials had sparked interest in the Church. Second, there were two stable, active families, the Rappleyes and Amparos, who were prepared to share the gospel and fellowship new families. Third, there were no political restrictions to impede missionaries from proselytizing. Fourth, Elder Ballard had acted on behalf of the leaders of the Church to give a dedicatory prayer and blessing upon the land and people. The next significant step was the additional leadership and experience to be provided by the first senior missionary couple, Jack and Ada Davis.

Dedication of the Dominican Republic for missionary work, presided over by Elder M. Russell Ballard, December 7, 1978. All images courtesy of the author.

Dedication of the Dominican Republic for missionary work, presided over by Elder M. Russell Ballard, December 7, 1978. All images courtesy of the author.

In January 1979 Jack and Ada Davis arrived in the Dominican Republic, where they served for the next four and a half years. The Davises’ special talents and their Spanish-language background proved to be effective missionary tools. Both were from the LDS colonies of Mexico, and each labored in their youth in the Mexican Mission during the early part of World War II. [7] Furthermore, Sister Davis had a do-it-yourself personality; she took the Church to another level of visibility beyond the Homefront commercials. When a Church-sponsored health fair arrived in the Dominican Republic, Ada Davis was interviewed on television. The interview went so well that Ada Davis and Church member Mercedes Amparo were invited to participate in a local weekly TV show to teach basic cooking and canning classes.

Sister Davis reminisced about the latitude she had on the show: “We could talk about everything [with] the Church. We were on one day, just after we had celebrated the 150th anniversary of the Church, and I told how there had been an apostasy and that was why a restoration was necessary.” [8] She discussed the Relief Society and the Primary programs and taught about the importance of a family home evening night. Previously, Irene Napier, the host of the show, had participated in a family home evening taught by the elders. Irene concluded a show focused on this subject by saying, “This is really a worthwhile program. The missionaries have been to our home, and I would advise that for anybody.” The TV show cameraman was later baptized, as were others who watched the show. [9]

One time, Ada Davis met the wife of the country’s president. The First Lady embraced Ada and said, “I know you. I know you.” To the housewives of the Dominican Republic, Sister Davis was a recognizable face, and she reached the hearts and homes of the people in a marvelous way. [10]

The Davises’ first eighteen-month mission was extended six months, and then they received a call from President Spencer W. Kimball to preside over the new Dominican Republic Mission, created in 1981. The Davises provided leadership to missionaries, welcomed and trained new converts to the Church, and continued to reach out to the general public through television. By the end of 1983, shortly after the Davises release, the Dominican Republic had grown to two districts and thirty branches. [11] That year the LDS population reached 6,415 and surpassed that of Puerto Rico. [12] A strong foundation for the Dominican Republic’s growth had been laid in only five years. In 1986 the first stake was created, and in 2000 the first temple was dedicated. [13]

The beginning of the Church in the Dominican Republic demonstrated the power of Spanish-speaking missionaries, senior missionaries, positive Church media in the mid-1970s, and members ready to start the Church after the 1978 revelation. On the other hand the friendly Dominicans were ready for the gospel; they were responsive and welcoming to the missionaries’ efforts to open this island of the sea.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico has the second-largest LDS population in the Caribbean. In 2010 there were just over twenty thousand members. [14] The country did not experience explosive growth in the same way as the Dominican Republic did, but during the Church’s infancy, the work of Frank and Arline Talley improved the image of the Church through a health fair. Frank Talley, a wealthy businessman, moved to Puerto Rico in the mid-1970s because of his manufacturing plant for airplane parts. He used his personal airplane and other resources to help further the work throughout the Caribbean. As counselor to several mission presidents, he would fly Church leaders throughout the islands. Talley also flew pioneer members to the United States to receive their temple blessings. [15]

Left to right: Darnell Jeffs, Frank Talley, and President Dean Jeffs in front of Talley's personal airplane.

Left to right: Darnell Jeffs, Frank Talley, and President Dean Jeffs in front of Talley's personal airplane.

The Talleys were the main sponsors of a traveling health fair through Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic in 1979 and the early 1980s. The basic principles of the Word of Wisdom and good health practices were used to teach correct principles and introduce people to the Church. The idea for the health fair came to Arline Talley when she visited her daughter in the Philippines and saw a health fair sponsored by the mission there. When Sister Talley returned to Puerto Rico, she received permission from the mission president to design a similar fair, which she developed at her own expense. Sister Talley worked with missionaries to make signs and displays and show the fair throughout the island. The traveling exhibits included puppet shows that taught dental care using a three-foot mouth with teeth. There was also a smoking machine that simulated lung damage. Sister Talley was dedicated to the project. She stated, “I was at the malls from eight thirty in the morning until ten at night every day six days a week. Then we’d set up on Sunday afternoon after church.” [16]

When the health fair came to Santiago, Dominican Republic, Pontifical Catholic University allowed the fair to be on their campus. One conversion that resulted from the health fair was Félix Sequi-Martínez, a former Catholic priest, who became an early stake president. [17] The health fair raised awareness of the Church in countries where the Church sought to develop a positive image. A second health fair was also used later in the 1980s to counteract negative publicity leveled against the Church in the West Indies.

Jamaica

Missionaries in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico did not have problems with visas or the government. Yet this was a challenge in Jamaica—a challenge first encountered in the 1850s during the only nineteenth-century mission to the Caribbean. [18] Negative publicity challenged the work in Jamaica from its beginnings. Six missionaries served in Jamaica in January 1853. They were James Brown, Darwin Richardson, Aaron Farr, Jesse Turpin, Elijah Thomas, and Alfred B. Lambson. A month later, they all had left the island. The fruits of their labors were the conversions of a British widow named Eliza Kay, her two grandsons, and an unnamed person. The opposition to the work came from outraged citizens and the British government.

An important media tool in the 1850s was the newspaper. Months before the elders arrived in Jamaica, the Church publicly announced the practice of polygamy. Newspapers carried the announcement around the world, inspiring both curiosity and outrage from the public and local ministers. The undesired result in Kingston, Jamaica, was that the first evening meeting organized by Mormon missionaries never began due to a mob of 150 people outraged by polygamy. The elders escaped out of the back of the building and climbed over a wall to safety. A few days later the elders were shot at while walking into their hotel. Their right to hold a meeting was not supported by Kingston’s mayor or the attorney general. With a public preaching venue denied them, some elders spent a few days teaching in the countryside away from Kingston. As a result of this opportunity, Darwin Richardson and Aaron Farr baptized a widow named Eliza Kay and her two grandsons, Joseph Piersey Smith and Frederick John Smith. [19]

The second impediment to the elders was political. The British government did not want the Mormons in Jamaica. Though missionaries had support from the American consul, the British would not help them by any means, except to aid them to leave the island to America or England. Attempting to further the work in other islands, Elders Jesse Turpin and Alfred Lambson bought passage to Barbados, but the harbor agent forcibly removed them from the ship. Due to this political persecution, the six elders soon left the island. Elder Richardson stayed longer to ordain Eliza Kay’s grandsons to the priesthood, and then he sailed for England. [20]

Jamaica’s modern beginnings. Ironically, similar government opposition to that affecting the short-lived Jamaican Mission in 1853 would repeat 125 years later. However, the Book of Mormon scripture from Words of Mormon 1:7 applies here. “The Lord knoweth all things which are to come.” He knew that after missionary work began in November 1978 an official of the Jamaican government would start restricting Mormon missionaries from receiving visas. [21] In some countries this would have blocked the Church work from commencing, but this time a political obstacle would not halt the work.

In most Caribbean countries, the Church started through the efforts of senior missionaries or young elders. The Church’s genesis in Jamaica, however, came through the work of US citizens working in Jamaica. Paul Schmeil shared the gospel with a fellow employee named Victor Nugent, who lived in Mandeville. Nugent was baptized in 1974, notwithstanding the restriction on the priesthood. He later taught the gospel to his friends Errol and Josephine Tucker, who joined in February 1978. Amos Chin, from Kingston, also attended meetings when he could make the two-hour bus ride to Mandeville. [22]

Amos Chin and political resistance. The experiences of Amos Chin offer critical insights into the political restrictions in Jamaica. Chin joined the Church in Montreal, Canada, in 1976. He had both Chinese and African ancestry. Shortly after joining the Church, he had a dream where he saw himself arriving in Jamaica as the first missionary there and teaching his family. Exhibiting the excitement of a new convert, he detailed his experience in a letter to President Spencer W. Kimball and received a polite thank-you letter back from Kimball’s secretary, Arthur Haycock. At the time, the thought of missionary service must have seemed very unlikely in Chin’s immediate future. [23] Then, following the 1978 priesthood revelation, Nugent, Tucker, and Chin were ordained to the priesthood. That same year Amos Chin was called to serve in the Florida Fort Lauderdale Mission under Richard L. Millett. After serving in Florida, Elder Chin transferred to Jamaica and was indeed the first native missionary there. The events from his dream transpired exactly as he had seen years earlier as he arrived in Jamaica and later taught the gospel to his family. [24]

Missionaries from the Florida Fort Lauderdale Mission found that Victor Nugent and Errol Tucker were already excellent member missionaries. Amos Chin stated: “Brother Nugent would be always proselyting every night with one of us, his sons, or the Tuckers . . . and that helped build the branch all the way up. . . . It was because of our local members who went with us doing missionary work that [it] was a success. We were just the helpers.” [25] The success of member missionary work was vital to the beginning of the Church in Jamaica because a visa-quota system began to stop the influx of missionaries. Because the Lord had provided the means for Jamaicans to join before the missionaries arrived, native leaders provided a proper foundation independent of the missionaries.

By the end of Amos Chin’s mission in 1980, severe restrictions had been placed on the granting of visas in Jamaica so that there were only two missionaries supporting the Mandeveille Branch. Unlike in the short-lived mission of 1853, in the twentieth-century mission there were several native Jamaicans who could exercise their religious rights on behalf of the Church. Chin recalled, “After I came off my mission there were no missionaries there [in Jamaica]. I was the only one representing the Church, because the mission president couldn’t. . . . There was a long time that I kept going back to the Minister of Labour for an application for the Church, for permission for work permits. They would have me sit there. I would be sitting there from eight o’clock in the morning. . . . At the end of the day they would say, ‘Come back tomorrow.’ I think it was over a period of three weeks that I sat in that office being treated unfairly by my own country just to get two American missionaries in.” [26]

One day, while waiting at the Ministry of Labour, a female official came over to Chin and in front of everyone in the office said, “Under no circumstances does one let missionaries into Jamaica anymore.” [27] Returning home, Amos Chin quietly took the matter to the Lord and prayed that the government official be removed from the post. The next week Chin returned to the Ministry office; the official was gone. An assistant in the office had replaced the woman. The assistant had observed Chin’s perseverance and granted the visas for missionaries to return to Jamaica. [28] Chin’s faith and patience were rewarded. However, the negative feelings of the Jamaican employee at the Ministry of Labour were indicative of strong emotions felt by some in the Caribbean, which disrupted the work in other nations.

While the exact reason for the government official’s antagonism is not known, there were scores of newspaper articles and debates throughout the 1980s about the Church’s history of restriction on the priesthood and whether Mormons should be allowed to proselytize in Jamaica. [29] Whereas the topic of polygamy filled the news in the 1850s, in the 1980s it was the arrival of Caucasian missionaries, who were perceived as representing a white church, that made Jamaicans uncomfortable. Fortunately, the stabilizing influence of native Jamaicans like Chin, the Tuckers, and Victor Nugent would aid the work for years to come. Ironically, the negative publicity leveled against the missionaries in the newspapers was what opened a dialogue about the Church’s beliefs. Honest seekers of truth learned about the Church, and membership quadrupled from 520 to 2,100 between 1985 and 1989, the greatest period of growth experienced to date in Jamaica. Twenty years later, Church membership exceeded five thousand. [30]

Grenada

Even as the Church developed a strong foundation in the countries of the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and also Haiti in the 1980s, several countries experienced a wave of negative effects from the release of The Godmakers. [31] Around 1987 a cruise ship employee named Rob Brooks started showing the film The Godmakers and sharing anti-Mormon publications whenever he docked in Caribbean countries. On some islands the film was shown in the only theater in the country. [32]

The people of Grenada were already suspicious of outsiders due to a recent event in Guyana where nine hundred followers of religious leader Jim Jones had committed suicide. Against this backdrop, West Indies Mission president Dean Jeffs explained, “Rob Brooks used the fear generated by the recent memory of those events to elicit help from the island’s religious and political leaders to oppose this new ‘American cult’ the Mormons.” [33] Brooks antagonized missionaries, and his negative campaign was instrumental in getting a senior missionary couple deported from Grenada. [34] Brooks also raised anti-Mormon sentiments in Barbados and Trinidad.

Arline Talley and a missionary talking to a group of adolescents at the Health Fair in Trinidad in January 1989. This was the second time the Talleys held the Health Fair in Trinidad.

Arline Talley and a missionary talking to a group of adolescents at the Health Fair in Trinidad in January 1989. This was the second time the Talleys held the Health Fair in Trinidad.

Trinidad

Meanwhile, attempts to open Trinidad for missionary work had been started by a senior missionary named Murray Richardson. Elder Richardson sent a petition to Trinidad’s parliament to allow missionaries to proselytize, but anti-Mormon efforts influenced parliament to deny the Church’s petition. [35] President Dean Jeffs explained, “The only way our missionaries could enter the country to do missionary work would be if some citizen requested in writing that missionaries come and teach him the LDS doctrines.” Even then, the missionaries could only teach that contact. [36]

In 1988 Frank and Arline Talley were visiting Trinidad. While checking out of the Hilton Hotel, Sister Talley saw some professional signs and inquired where they had been made. Upon learning that they were made in Trinidad, the Talleys canceled their plans and visited the sign maker; soon the idea of a second health fair began to be a reality. The project ultimately cost Brother Talley sixty thousand dollars to build and another sixty thousand for import duty just in Trinidad. [37] However, the new fair traveled widely to Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad, Costa Rica, and Guatemala. The fair ultimately opened the missionary door into Trinidad.

The conversion of Kelvin Díaz. In early 1988 the Talleys had set up the new health fair in the only mall in Trinidad. Joining them were two missionaries, Robert Jaeger and Jeff Nalwalker, who were in the country as tourists and who collected referral cards from people who wanted to hear more about the Church. One visitor to the health fair was Trinidad’s Boy Scout commissioner, a retired gentleman named Kelvin Díaz. He was interested in whether Trinidad’s 2,500 Boy Scouts should visit the fair. He was favorably impressed, and upon leaving to go to his car, he heard a voice say to him, “Go back and find out who they are.” Díaz had been raised as a Catholic and believed the voice was his guardian angel. He then returned to the fair and noticed the Church’s film Man’s Search for Happiness and signed a referral card. He was one of 350 interested people that missionaries contacted from health fair referrals. [38] The referral cards opened the door for missionaries to legally contact those interested Trinidadians who visited the fair.

Kelvin Díaz progressed through the missionary discussions, and “as [Kelvin] neared baptism he asked the elders why there were no regular missionaries in Trinidad.” They explained the Church’s predicament. Díaz “answered by saying, ‘Do you know who I am?’ Then he explained that he was the retired senior civil training officer for the government of Trinidad. Continuing, he related: ‘All the people who need to be involved to grant the Church permission to have missionaries here are my students. You get me ten applications for missionary work permits . . . and I will get approval for ten elders to come here and do missionary work.’” [39] Kelvin Díaz fulfilled his promise of ten approved applications, and he joined the Church. He later served as a counselor to mission president Dean Jeffs.

Kelvin Diaz (left) serving as second counselor to mission president Dean Jeffs (center), and Arden Hutchings (right).

Kelvin Diaz (left) serving as second counselor to mission president Dean Jeffs (center), and Arden Hutchings (right).

“The Savior truly loved fishermen.” New converts that came as a result of the health fair enabled the Church to organize more branches in Trinidad. Yet parliament’s restriction on proselytizing still existed. The solution to this problem began with the call of a senior couple to the West Indies Mission in December 1988. When Donald and Doris Adams reported to President Jeffs in Barbados, Brother Adams explained that he wanted to teach poor fishermen the latest commercial fishing skills, which he had gained in Oregon after retiring from the Air Force. Unfortunately, at the moment President Jeffs had the pressing need to call Brother Adams as branch president in Antigua. Elder Adams’s parting words at the interview were, “You know President Jeffs, the Savior truly loved fishermen.” [40] It is not surprising that an opportunity would soon open for Elder Adams, who had such faith and interest.

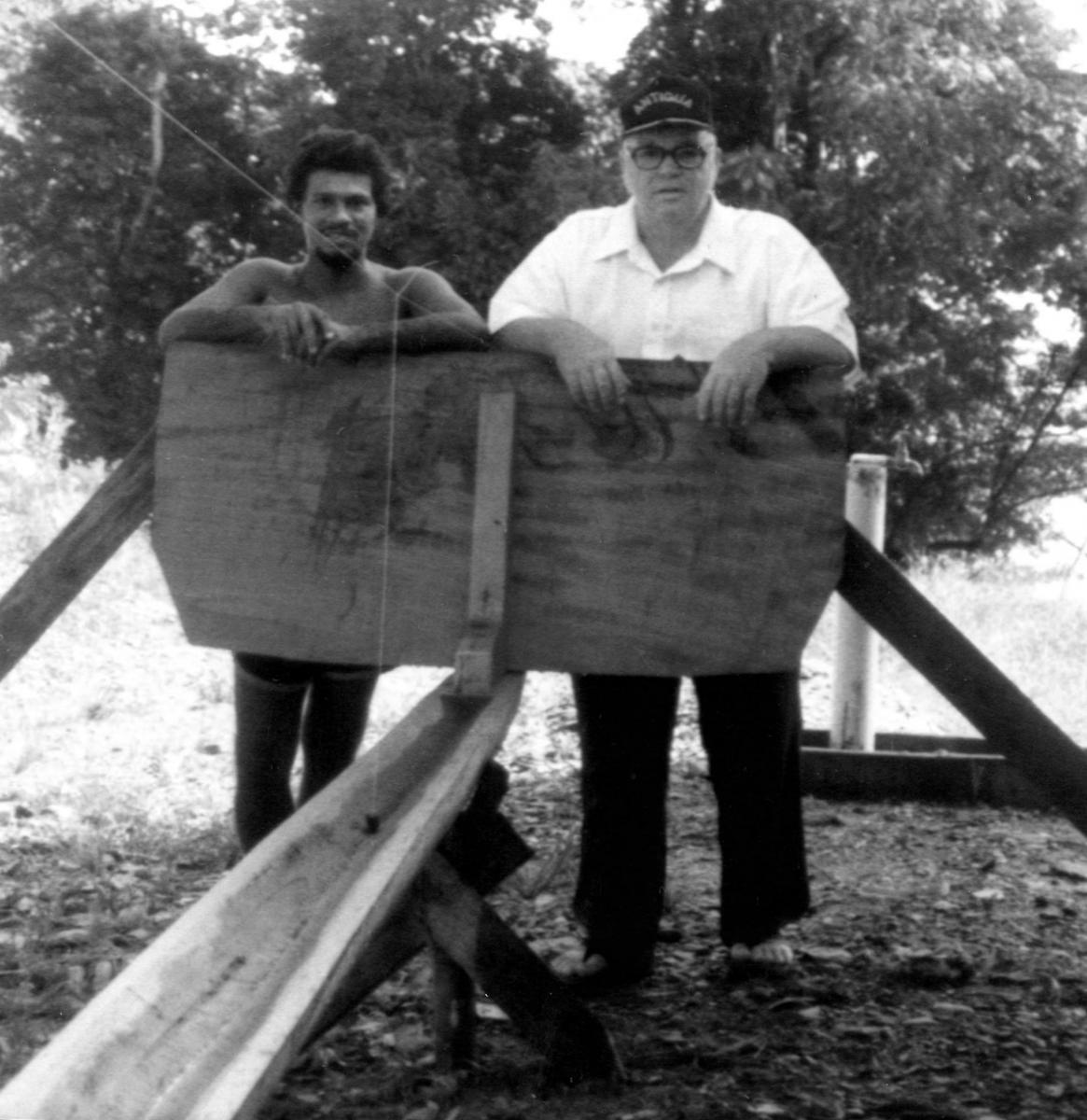

In January 1989, President Jeffs met with parliamentary minister Joseph Toney of Trinidad. Minister Toney represented the northeast corner of the island, which was mostly inhabited by poor farmers and fishermen. Minister Toney wondered if the Church could send someone to help improve these people’s skills. Already aware of a fisherman like Donald Adams, the Lord was providing the means to solve the problems of both poor fishermen and his Church. In March 1989, Elder and Sister Adams were transferred to the remote village of Toco to do humanitarian work only. Elder Adams taught compass and navigation skills so that Toco’s fishermen could make larger catches farther out at sea. He also worked with the fishermen to repair and build better boats. Sister Adams volunteered as a secretary at the local Catholic school. At the end of their mission, the Adamses were allowed to baptize a couple of people from the area. The good work of these missionaries and others who followed changed the hearts of common people in Trinidad and was noticed by men like Minister Toney.

Elder Donald Adams (right) working with a local fisherman in Trinidad.

Elder Donald Adams (right) working with a local fisherman in Trinidad.

Mission president Dean Jeffs saw firsthand the principle that Ammon demonstrated among King Lamoni’s people in the Book of Mormon. Service can be a great key to unlocking the hearts of people and politicians. Before President Jeffs finished his mission in 1991, the restrictions placed by Trinidad’s parliament had been lifted, and there were almost forty missionaries serving on the island. [41] The Church in Trinidad continued to grow, and by 2010 the country had one stake and 2,695 members. [42]

The miracle of the storm at the dedication of Trinidad. Before concluding his mission, President Jeffs was also able to witness the dedication of the country of Trinidad by Elder Russell M. Ballard, who, as an Apostle in the Church, had continued to witness the growth of the Church in the Caribbean. Elder Ballard’s dedicatory prayers for the Dominican Republic in 1978 and Trinidad in 1990 stand as bookends to the opening of the work in the Caribbean Islands.

An unusual event observed by Elder Ballard and President Jeffs during the dedication of Trinidad in 1990 deserves discussion. Behind the audience in the distant sky arose a huge black storm that rolled toward the dedication site, threatening to disrupt the meeting. Elder Ballard asked President Jeffs if they could move inside, but that wasn’t an option. Seconds later Elder Ballard whispered to President Jeffs, “That cloud is going to split in two. That half of it is going to go that way, and that half is going to go that way, and we’ll be just fine.” Indeed, in a few moments the dark cloud divided and circumvented the dedication site. The meeting continued with the audience unaware of the miracle that the two leaders had witnessed. [43]

The image of an unseen power dividing the storm serves as a powerful metaphor for the progress of the Church in its modern beginnings in the Caribbean. There are so many forces at work in the world that affect when the Church can open a country and also how slowly or quickly the work grows. In the case of the Dominican Republic, positive factors produced a large harvest. Jamaica, Trinidad, Grenada, and other countries experienced forces that temporarily disrupted the work. But there was always an unseen hand that could divide the storm, clearing the way for the Church to gain its footing.

As stories of the Church’s beginnings in every country are told, the handiwork of the Lord is seen through the efforts of common people who strive to accomplish his purposes both boldly and subtly amid many people, cultures, and nations. This paper has mentioned the contributions of normal Latter-day Saints like the Davises, the Talleys, Amos Chin, the Adamses, and Kelvin Díaz. These servants and many others were placed in their fields of labor in the Caribbean so that between 1978 and 1990 the work of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ could commence in these islands of the sea.

Kelvin Diaz speaking at the dedication of Trinidad for missionary work, presided over by Elder M. Russell Ballard, February 22, 1990.

Kelvin Diaz speaking at the dedication of Trinidad for missionary work, presided over by Elder M. Russell Ballard, February 22, 1990.

Notes

[1] Richard L. Millett, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Caribbean, 1977–1980,” 48, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[2] “Dominican Republic,” Deseret News 2011 LDS Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2010), 475.

[3] “Dominican Republic,” 2011 LDS Church Almanac, 475, 598.

[4] Kevin L. Mortenson, comp., Witnessing the Hand of the Lord in the Dominican Republic, 1978–1983 (Centerville, UT: Kevin L. Mortenson, 2009), 47–48.

[5] John E. Rappleye, Oral History, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 2001, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 15–16.

[6] Mortensen, Witnessing, 47–48.

[7] John and Ada Davis, preface to Oral History, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 2001, The James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[8] Davis, Oral History, 21–22.

[9] Davis, Oral History, 21–22.

[10] Davis, Oral History, 21–22.

[11] Directory of General Authorities and Officers, 1984 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1983), 132.

[12] “Dominican Republic,” Deseret News 1985 LDS Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1984), 254.

[13] “Dominican Republic,” Deseret News 2011 Church Almanac, 476.

[14] “Dominican Republic,” Deseret News 2011 Church Almanac, 476.

[15] Arline Talley, Oral History, interview by Joseph and Julie Todd, 1999, 7–8, in author’s possession.

[16] Talley, Oral History, 7–8.

[17] “Dominican Republic,” 2011 LDS Church Almanac, 476.

[18] “Jamaica,” Deseret News 2008 LDS Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2008), 398. Joseph Smith had Jamaica in mind for missionary work when he called Harrison Sagers to serve there in 1841 after Sagers served successfully in New Orleans, but there is no evidence that Sagers ever went to Jamaica.

[19] Aaron F. Farr to George A. Smith, June 2, 1865, Correspondence, Missionary Reports, 1831–1900, Church History Library; Aaron F. Farr, Diary, January 25, 1853, Church History Library.

[20] Farr, June 2, 1865, Correspondence.

[21] Amos B. Chin, Oral History, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 2003, 9–10, The James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library.

[22] “Jamaica,” 2011 LDS Church Almanac, 512–13; Chin, Oral History, 4.

[23] Chin, Oral History, 2.

[24] Chin, Oral History, 5.

[25] Chin, Oral History, 6–7.

[26] Chin, Oral History, 9.

[27] Chin, Oral History, 10.

[28] Chin, Oral History, 10.

[29] Jamaica Kingston Mission, “Jamaica Newspaper Clippings, 1980–1983,” Church History Library.

[30] “Jamaica,” Deseret Morning News 2008 LDS Church Almanac, 398.

[31] Randall A. MacKey, “The Godmakers Examined,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 18, no. 1 (Summer 1985): 14.

[32] A. Dean Jeffs, “Missionary Challenges in Grenada,” A. Dean Jeffs Papers, Church History Library, 2.

[33] Jeffs, “Missionary Challenges,” 2.

[34] Jeffs, “Missionary Challenges,” 3–4.

[35] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad to Our Missionaries,”A. Dean Jeffs Papers, Church History Library, 1–2.

[36] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad,” 2.

[37] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad,” 2.

[38] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad,” 4.

[39] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad,” 4.

[40] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad,” 6–7.

[41] Jeffs, “Opening Trinidad,” 9–12.

[42] “Trinidad,” Deseret News 2011 LDS Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2010), 594.

[43] A. Dean Jeffs, Oral History, interview by Clinton D. Christensen, 2003, The James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, 30.