A Place for "the Weary Traveler"

Nauvoo and a Changing Missionary Emphasis for Church Historic Sites

Scott C. Esplin

Scott C. Esplin, "A Place for 'The Weary Traveler': Nauvoo and a Changing Missionary Emphasis for Church Historic Sites," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 397–424.

Scott C. Esplin was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

Outlining the settlement of Nauvoo in 1841, the Lord told Joseph Smith that the town would be a place where “the weary traveler may find health and safety while he shall contemplate the word of the Lord; and the corner-stone I have appointed for Zion” (D&C 124:23). Because of opposition, however, the Church was able to comply with the Lord’s vision for the City of Joseph for only five brief years until it relocated west in 1846. Over the second half of the twentieth century until now, the Church has returned to many of its historic sites, including Nauvoo, seeking to fulfill the scriptural command to establish places where visitors can learn about the Church in a nonthreatening manner. As one of the most frequently visited Church historic sites, Nauvoo is an interesting example of missionary work at historical locations. The town itself offers a space for the unique interaction of various faiths, a place where Latter-day Saints work in concert with friends in the Community of Christ as well as with those belonging to Catholic and Protestant traditions. Additionally, it offers a fascinating blend within the Church itself of the missionary, temple, and historical departments, all of which have an important interest in the way Nauvoo portrays its message. Finally, with its member and nonmember audiences, Nauvoo demonstrates the tension present in the missionary message of Church historic sites. In many ways, the story of the Church’s return to Nauvoo demonstrates the changing nature of missionary work at historic sites during the twentieth century while serving as a pattern for how the Church uses its historic sites as missionary tools to share the gospel message.

Returning to the City of Joseph

As he bid farewell to a city he had helped build, Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal on May 22, 1846, “I Left Nauvoo for the last time perhaps in this life. I looked upon the Temple & City of Nauvoo as I retired from it & felt to ask the Lord to preserve it As A monument of the sacrifice of the Saints.” [1] Hopes for a monument turned to promises for a return to Nauvoo after the Saints settled in the West, where John Taylor prophesied:

As a people or community, we can abide our time, but I will say to you Latter-day Saints, that there is nothing of which you have been despoiled by oppressive acts or mobocratic rule, but that you will again possess, or your children after you. Your rights in Ohio, your rights in Jackson, Clay, Caldwell and Davies [Daviess] counties in Missouri, will yet be restored to you. Your possessions, of which you have been fraudulently despoiled in Missouri and Illinois, you will again possess, and that without force, or fraud or violence. The Lord has a way of His own in regulating such matters. [2]

More than a century later, this return has occurred, though likely different from how Taylor or the early Saints envisioned.

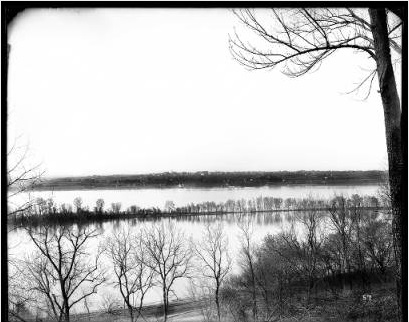

George Edward Anderson, Nauvoo from Bluff Park, Iowa, May 2, 1907. Wilford Woodruff once recorded a hope that the temple and city would stand as "a monument of the sacrifice of the Saints." Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

George Edward Anderson, Nauvoo from Bluff Park, Iowa, May 2, 1907. Wilford Woodruff once recorded a hope that the temple and city would stand as "a monument of the sacrifice of the Saints." Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

While the formal return of the Church was still more than a generation away, missionary interest in Nauvoo increased near the turn of the century. In 1901, while serving a mission in southern Illinois, Elder Thomas H. Burton wrote of visiting Nauvoo with Elders F. S. Parkinson, B. M. Olson, and W. A. Wilcox. The four toured prominent residences and civic structures, all of which, Burton noted, were “very large and durable,” evidence that the early Saints had “built to stay.” Commenting on the city’s thirteen hundred residents, “mostly all Germans” with a “Catholic element,” Burton reported the local attitude toward the Church: “We had the pleasure of meeting a number of prominent citizens and aged veterans, and after conversing with them. . . . I am pleased to note that the prejudice which used to exist in that city against our people is almost abolished.” [3] Visits like these continued until, by 1905, local hotel proprietors reported having “quite a bundle of namecards of Elders who have visited the city in the past.” [4] In fact, the same year, missionaries laboring across Illinois descended on the town, bringing “upwards of 100 Elders and visiting Saints.” [5] The gathering was highlighted by visits to prominent sites and the baptismal service of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Grimes and their daughter Sylvia, residents of the old Mansion House. [6] Positive reports from experiences like these filtered back to Utah, where the Deseret News editorialized, “People in Nauvoo are very friendly and anxious to have the ‘Mormons’ come back and help revive the town to its former condition. . . . As many as 2,500 copies of the Book of Mormon have been sold in one month.” [7]

Increasing interest in the site, coupled with the positive reception by local residents, led the Church to pursue a formal missionary return to Nauvoo. In 1933, the Church placed its first marker in the city, a memorial for the organization of the Relief Society, originally located at the site of Joseph Smith’s Red Brick Store. [8] The success of these and other endeavors led Northern States Mission President Bryant S. Hinckley to use the restored city as a missionary tool. In 1936, he made arrangements to renovate the Carthage Jail, which Joseph F. Smith had purchased from Mrs. James Browning in 1903 for $4,000, the first formal Church purchase of an historic structure. [9] At the same time, Hinckley and the Church organized a series of commemorations in the City of Joseph, beginning with the 1939 centennial celebration of the city’s founding and concluding with a 1947 centennial caravan retracing the exodus from the city. In each case, nearly two thousand Saints and citizens participated. Bryant Hinckley entertained the most ambitious idea of all—that of reconstructing the Nauvoo Temple, a dream that was later fulfilled by one of his sons, Gordon B. Hinckley. Describing the effect a restoration of Nauvoo would have on missionary work, Bryant Hinckley predicted, “The Nauvoo visitor of today lingers: he is interested; there is something about the quiet atmosphere of that dream city that charms and fascinates him: it speaks of the past: he feels reverent.” Hinckley projected the result of capitalizing on this interest, saying, “As . . . developments go forward, Nauvoo is destined to become one of the most beautiful shrines of America and one of the strong missionary centers of the Church.” [10]

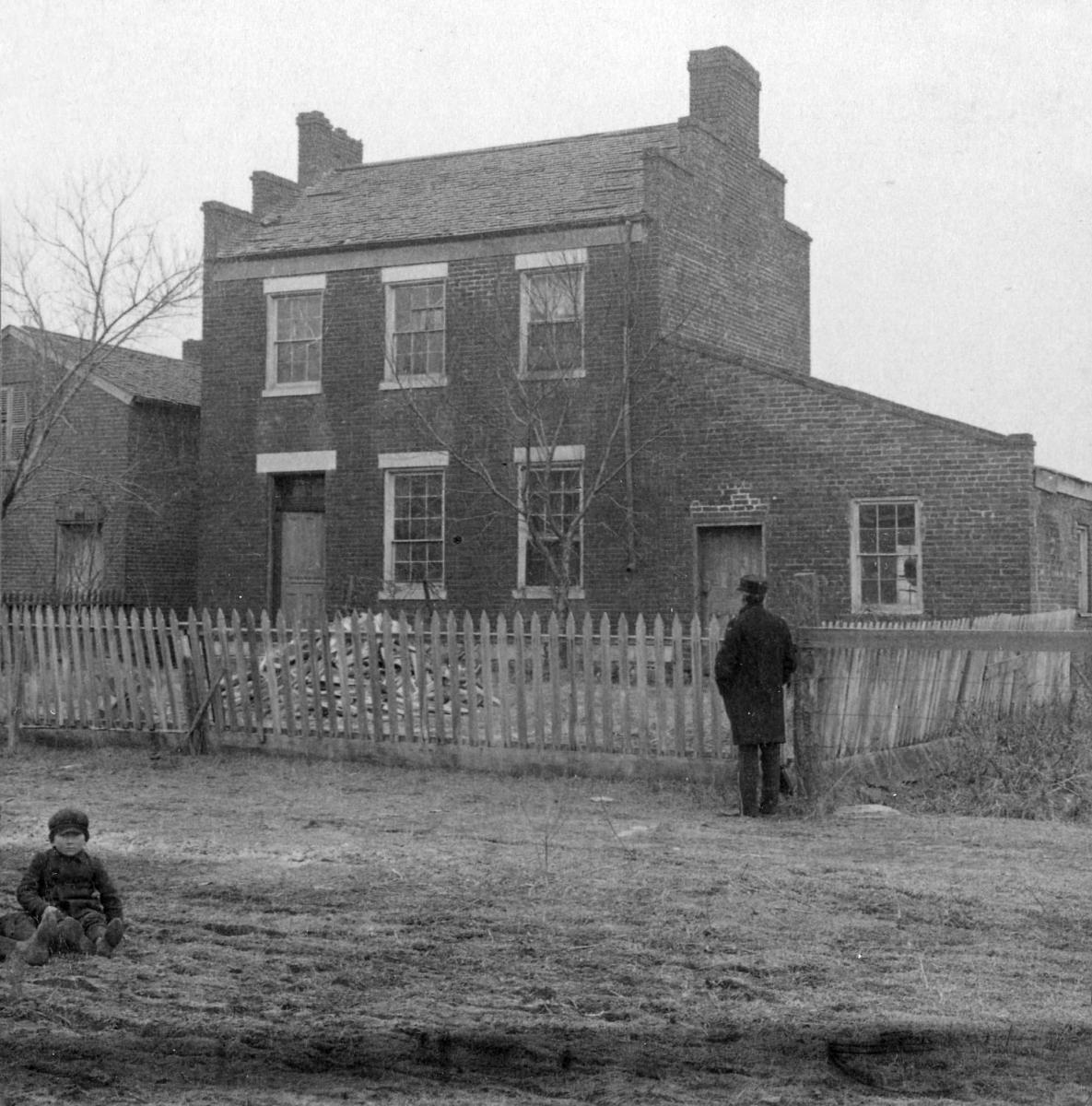

The first marker in Nauvoo, a memorial for the organization of the Relief Society, was placed here in 1933 at the site of Joseph Smith's Red Brick Store. George Edward Anderson, Site of the Red Brick Store, 1907.

The first marker in Nauvoo, a memorial for the organization of the Relief Society, was placed here in 1933 at the site of Joseph Smith's Red Brick Store. George Edward Anderson, Site of the Red Brick Store, 1907.

While Hinckley envisioned a missionary focus for a restored City of Joseph, entrepreneur Wilford C. Wood quietly went about acquiring historical properties in Nauvoo. Purchasing the Times and Seasons office in the 1930s and deeding it to the Church, which began holding Sunday School meetings in the building, Wood turned his attention to a more significant prize—the Nauvoo Temple lot itself. Wood and the Church eventually acquired the entire property through a series of transactions lasting nearly three decades. Acquiring the temple lot eventually led to an official missionary presence in Nauvoo when the Church established a Bureau of Information in a vacant home on Nauvoo’s Temple Square in 1951. [11] Two years later, Elder and Sister David Haycock became the first missionary couple to live in an early Latter-day Saint home in the city when they moved into the John Taylor home, transforming it and the adjacent Times and Seasons building into a “Church education center.” [12]

John Taylor home, ca. 1904. This building was the first early Latter-day Saint home in Nauvoo that housed a missionary couple. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

John Taylor home, ca. 1904. This building was the first early Latter-day Saint home in Nauvoo that housed a missionary couple. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Preaching History

Though Bryant Hinckley and Wilford Wood sought to use Nauvoo’s historic past for missionary purposes, Salt Lake City physician Dr. J. LeRoy Kimball made the most significant impact on how the historic site would be used to represent the Church throughout the twentieth century. Kimball, who had studied medicine in Chicago in the 1930s, returned to Nauvoo in 1954 and successfully purchased his great-grandfather Heber C. Kimball’s home. Remodeling it as a summer retreat while maintaining, in part, its 1840s charm, Dr. Kimball invited Elder Spencer W. Kimball, a fellow Heber C. Kimball descendant, to dedicate the home in 1960. [13] Surprised by the interest the renovation generated, Dr. Kimball set about acquiring historically significant properties in old Nauvoo, a process that culminated with the incorporation of Nauvoo Restoration, Inc. (NRI), by the Church’s First Presidency on July 27, 1962. [14]

With incorporation came legitimacy, something Dr. Kimball parlayed into transforming Nauvoo into the Church’s most ambitious historic sites project. Initially, the reconstruction of the city under the auspices of Nauvoo Restoration, Inc., emphasized the historical aspects of the city. Designed as “A Williamsburg of the Midwest,” NRI’s Articles of Incorporation outlined its mission:

To acquire, restore, protect and preserve, for the education and benefit of its members and the public, all or a part of the old city of Nauvoo in Illinois and the surrounding area, in order to provide an historically authentic physical environment for awakening a public interest in, and an understanding and appreciation of, the story of Nauvoo and the mass migration of its people to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake in the area which has now become the State of Utah; to interpret and dramatize that story, not only as a great example of pioneering determination and courage, but also as one of the vital forces in the expansion of America westward from the Mississippi River; to engage in historic and archaeological research, interpretation and education and to maintain, develop and interpret historic landmarks and other features of historic, archaeological, scientific or inspirational interest anywhere in the United States and particularly along the Mormon Pioneer Trail from Nauvoo, Illinois to its terminus in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. [15]

True to this charge, missionary work in Nauvoo in the 1960s reflected the historical emphasis of Nauvoo Restoration. Early NRI pamphlets highlighted Nauvoo’s connection to the American westward migration rather than the Church’s core message regarding the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. Frequent reference was made to a National Park Service report touting “the movement of the Mormons to the valley of the Great Salt Lake [as] one of the most dramatic events in the history of America westward expansion.” [16] From a missionary perspective, the message of Nauvoo was to connect the faith to the whole of America rather than to emphasize the mission of the Prophet Joseph Smith.

The makeup of NRI’s original board, together with the early participants in its projects, reflected this emphasis on history rather than on proselyting. Board President J. LeRoy Kimball was joined by A. Hamer Reiser, former chairman of the Utah State Parks and Recreation Commission and assistant secretary to the First Presidency; prominent LDS businessmen David M. Kennedy and J. Willard Marriott; and a non-Mormon, vice president Harold P. Fabian, who was a member of the US Department of the Interior’s advisory board on national parks. The connection to National Historic Sites was strengthened when the board added A. Edwin Kendrew, senior vice president and chief historical architect for the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, as an adviser in 1962 and as a board member in 1965. [17]

Fabian championed the historical emphasis for Nauvoo’s restoration. Early in the project, he cautioned President David O. McKay regarding proselyting: “If you undertake to restore it as a religious restoration, as a proselyting institution to get members to your church, it will not be received generally and will not have the approval of the nation. But if you will restore it as an historic restoration it must be based on all of the best things that your church has to offer and has had to offer in history and must give you all of the benefits and standing which you would not get if you tried to restore it as a religious restoration.” [18] In particular, Fabian emphasized the faith’s connection to westward expansion. Indicating that Fabian “had no patience with the proselyting interests” of the Church, Reiser reported that “on several occasions he mentioned the fact that the less we had to say about Joseph Smith the better it would be.” [19] Following Fabian’s lead, Dr. Kimball downplayed the missionary effort in favor of the historical, declaring, “This could not be a proselyting operation but should be handled as a historical restoration in order to retain its national stature, but that through the referral system it could result in real missionary work.” [20]

Early NRI projects reflected this emphasis on the historical. The most prominent of these were the archaeological excavations from 1966 to 1969 conducted by J. C. Harrington, the father of historical archaeology, and his wife, Virginia. The Harringtons, who had gained prominence in their interpretive work at the settlement of Jamestown and in J. C. Harrington’s excavations of Fort Raleigh, North Carolina, and Fort Necessity, Pennsylvania, directed the excavation of five historic sites in Nauvoo, most prominently among them the temple site itself. [21] Updates on the excavations regularly appeared in local newspapers, where project field supervisor Dee F. Green stressed its historical aspects: “When the entire [temple lot] is cleared, it should be done with the idea of preserving the wood and charcoal fragments [from the building’s burning] on the floor. As a permanent display, it could be covered with glass or plastic to protect it from the elements, and at the same time allow visitors to view the remains.” [22]

While work moved forward in the restored historic district, plans for Nauvoo quickly expanded beyond the historical. Two short years after incorporation, NRI’s official “Report of Progress and Development” already speculated on the erection of a “full temple facility” off the site of the original Nauvoo Temple, together with a university, visitor accommodations, an orientation center, a golf course, an amphitheater, and a marina. [23] One regional magazine reported, “Final plans call for complete family vacation facilities, including boating, horseback riding, hiking, tourist lodges, shopping, and restaurants.” [24] In the Church’s Improvement Era, J. LeRoy Kimball himself announced plans to ferry visitors on historic steamboats, as well as hopes to establish NRI-owned motel-hotel accommodations. [25] Philosophically, Kimball remarked, “Nauvoo is a great center from which to tell many stories: The Mormon Nauvoo story, the migration story of all peoples who headed westward, the Mississippi River traffic and merchandising story, and the always enjoyable experience of seeing how people of another time lived.” [26] Indeed, “there is no end to what can be done in Nauvoo,” Kimball later remarked. [27] By going beyond mere historical restoration to appeal to tourist interests, early NRI plans, in fact, followed the pattern outlined by the Lord for the establishment of Nauvoo: “Let it be a delightful habitation for man, and a resting-place for the weary traveler, that he may contemplate the glory of Zion, and the glory of this, the corner-stone thereof” (D&C 124:60).

From a missionary perspective, Dr. Kimball envisioned using restored Nauvoo as a nontraditional means for sharing the gospel message. “The role of the Church in restoring Nauvoo envisions a different approach to missionary work,” Kimball remarked. “Our guide service is one that tourists will find informative, educational, and inspiring, but also one that those who do not desire a proselyting approach will find acceptable. Nauvoo will be a historical place where people will first look and then possibly listen to the gospel message.” [28] Speaking to the Rotary Club of Burlington, Iowa, NRI manager J. Byron Ravsten reassured locals about the endeavor’s emphasis, saying, “Nauvoo Restoration is a historical and not a religious project.” [29]

Implementing this approach was easier said than done, however. To facilitate crowds, NRI organized a guide service composed of volunteer couples personally selected by Dr. Kimball, augmented in the summer months by college students from BYU and elsewhere. Using “experience at various museum cities and restoration projects,” NRI officials established two basic principles for guide service. First, they sought to emphasize buildings that were unique. Acknowledging that “the architecture of Nauvoo houses was not a new type and made no impression on the development of American architecture” and also that “no Nauvoo building is associated with a great historical event,” NRI officials chose to focus on the temple, which “was unique—there was only one of its type—and has never been duplicated.” Second, guides were instructed to emphasize the people and their lives rather than the buildings. “The men who built and inhabited these houses,” officials stressed, “were more important than their dwellings. Their personal achievements, their impact on other people, their influence on the community and the country as a whole, their relationship to the social, political, or religious institutions of the community, or their influence upon a region of the country—such as the expansion of American institutions to the Far West—should be our stock in trade, rather than the houses in which they dwelt.” Applying this principle to Nauvoo, guides were instructed,

It is in these areas that Joseph Smith, Heber C. Kimball, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, Orson Hyde and others should be discussed. Their contributions in the field of city planning, religious leadership, pioneering in the Far West, and similar achievements become the vehicle for telling the story of Nauvoo’s importance in the contemporary setting of the 1840’s. The houses are but structures in which to place the men and their families as living people, facing problems people face today, and to indicate how they solved their problems through their religious convictions, their ability to cooperate to a remarkable degree, and to show the cultural level they were striving to maintain in spite of economic adversity and opposition from their neighbors who failed to understand their motives. [30]

While early NRI guides sought to implement these principles, adaptation was necessary, especially for the various groups attracted to the restoration project. In particular, the religious component of the endeavor challenged early guides, as it might challenge modern guides today. NRI officials further counseled:

At Nauvoo, many tourists are met who belong to the various churches which have descended from the Nauvoo Mormon Church. The interest of those people in Nauvoo is very different from that of the majority of the tourists. They are very interested in the religious life of the city and the rapid growth of the city through its missionary system. Many are blood descendants of those who resided in Nauvoo. They want to hear of their ancestors even though they were not prominent in the city’s history. The guide must have a treasury of information concerning people and items which are of little interest to the majority of tourists but which will give these Mormons a great thrill of pride and a vicarious feeling of participation with their ancestors in the rise and fall of Nauvoo. [31]

This model furthered the historical emphasis of the project. Charles A. Lipchow, blacksmith and guide at the Chauncey Webb blacksmith shop, summarized the approach of the era: “We do not preach the Church at the restoration; we preach history.” [32]

Preaching history in Nauvoo without emphasizing the Church and its teachings was not without its problems. NRI secretary Rowena Miller articulated the challenge presented by conducting missionary work in a historical recreation. She wrote, “It will take the wisdom of a Solomon to walk the tight-rope of historic interpretation/

Two groups in particular were most vocal about the Church’s increasing missionary presence in the City of Joseph. The first was the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS, now known as the Community of Christ), who, by virtue of their ownership of the Joseph Smith family sites, had controlled the Mormon message in Nauvoo since the exodus of 1846. Tracking the growing LDS presence, RLDS leaders became alarmed with the missionary impact of Nauvoo’s restoration. In 1961, RLDS Apostle Donald V. Lents wrote to the RLDS First Presidency, summarizing the city’s missionary developments:

The Mormons are stepping up their program for the purchase of property in the area and seem, too, to be increasing the number of personnel in responsibility here in the town. I am informed that they have a full-time couple at the Heber Kimball home to tell the story. Of course at their Information Center they also have a full-time couple to answer questions and direct folk on tours of the town. They have two more full-time people at the home they call the John Taylor house. They have just purchased the Brigham Young home and report is they will renovate it and provide caretakers and guides.

Troubled by the expansion, Lents cautioned, “We certainly need to be alert to some of the moves in the town. The couples the Mormons have sent in are cultured, well-appearing people that make a fine appearance.” [34]

While the RLDS Church was concerned with the missionary message of the NRI project, longtime residents of the city were confused by its direction. In 1970, Elmer Kraus, local businessman and president of the Nauvoo Chamber of Commerce, remarked, “We are not a part of the big plan. Never was the community invited to share in their plans. . . . To date . . . the community has not been shown the Mormons’ master plan for Nauvoo. And in back of it all they keep saying ‘Look what we are doing for you.’ But I’m afraid,” Kraus continued, “that they are just doing it for themselves.” Acknowledging that he “was happy to see the restoration of these old homes” and that “the Midwest is fortunate that this is being done on a quality basis,” Kraus nevertheless concluded, “I think we should try to help and still keep our identity. But no one likes to be pushed around, or ignored.” [35] Longtime Nauvoo resident James W. Moffitt expressed similar concern regarding the marginalization of local interests: “I don’t see any reason why Nauvoo can’t maintain some of its own identity, along with something this massive. Nauvoo has a lot of history besides just the Mormon history. The Indian lore, the Icarians, the wine industry, the cheese industry—I mean, it’s full of history. And I like to hope it can maintain its own identity along with the Mormons.” [36]

Local concern was reflected in the town’s 1970 “Contemporary Planning in Nauvoo, Illinois” report. “One significant problem that plagued the planning program from its inception,” the study noted, “was the reluctance of Nauvoo Restoration, Inc. to freely discuss its plans for the Mormon holdings (the area comprising one-half of the corporate limits). . . . Reports in nationally circulated publications, however, have stated that Nauvoo Restoration planned to develop motels, restaurants and other facilities for tourists. This naturally concerned local influentials who also have plans relative to facilities that would provide services needed by tourists that would be attracted to the area.” [37] Reflecting on these frustrations, David A. Knowles, Nauvoo mayor during the early historic restoration, vocalized his concern: “The problem with the Mormon Nauvoo Restoration, Inc., is that it was super secret. Dr. Kimball said that the NRI ‘was not going to be a big deal. We are just buying a few houses, putting them together, and remodeling them, making them look good.’ Maybe this is what he had in mind at the particular time,” Knowles concluded, but as plans changed, it clearly created “a lot of animosity.” [38] Nauvoo residents felt left out of their city’s resurgence.

A Move to Traditional Missionary Work in Nauvoo

Voices of dissent against the Church’s proselyting through restoration were not limited to those outside the faith. Within Church leadership itself, some questioned the historical emphasis evident in the project. NRI board secretary Rowena J. Miller summarized the shift: “The restoration was administered as an historical project, as outlined in the Articles of Incorporation, and the purpose for which the corporation was set up. With two non-members on the Board of Trustees, the corporation had a standing in the nation as an historical restoration project. . . . After the death of President David O. McKay, who had supported the corporation in all of its activities, there were some in the officialdom of the Church who did not believe in the historical approach of the restoration.” [39] Those most concerned appear to have been President McKay’s immediate successors, Joseph Fielding Smith and Harold B. Lee. One historical consultant to the project, T. Edgar Lyon, recalled President Smith’s concern: “This isn’t missionary work. This is just entertaining the gentiles.” Lyon likewise reported President Lee’s reaction: “The money that’s going in back there can better be spent for helping the Church in lands where they need schools and where we can make more converts as a result of it. We can do greater missionary work there than we can back there [in Nauvoo].” [40] Early Nauvoo restoration guide and later Church historic sites researcher Don Enders summarized the shift in emphasis. He said, “The Church could restore one house in Nauvoo, or pay for five full-time seminary teachers in Central America with the same amount of money.” [41]

In the end, employing a more traditional missionary perspective for Nauvoo won out. On May 13, 1971, the Board of Trustees for NRI was reorganized. While Kimball was retained, Fabian, Kendrew, Reiser, Kennedy, and Marriott were moved into advisory positions as Elders Mark E. Petersen and Delbert L. Stapley of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles assumed positions on the board itself. [42] Outgoing board members sensed a change in focus. In his benedictory remarks, Kendrew cautioned the new board “to be very careful about [a] missionary emphasis which may offend more people that you attract,” calling it “a great mistake if [the Church] lured people here on the basis of a historic site and then took the opportunity for excessive proselyting.” [43] For his part, Fabian continued to champion Nauvoo’s connections to the American past, emphasizing that “Nauvoo was a great story, a great American story, that of an historic movement with its origins in the religious.” [44] However, instead of connecting Nauvoo to the American story, Elder Petersen was determined to link Nauvoo to the Church’s missionary approach elsewhere, indicating that work at Church historic sites “was localized and interpreted [in] its relation to the history of the Church and that the Nauvoo Visitors Center and historic area would tell the story of the Nauvoo period.” [45]

Exerting further control over the missionary potential for Nauvoo, the Church also created a Nauvoo Mission in 1971, with Dr. J. LeRoy Kimball as the mission president. As during the earlier era, the mission continued to be staffed by volunteer couples. However, as an official mission, calls were channeled through the Church’s missionary department rather than offered as personal invitations at the hand of Dr. Kimball. Furthermore, focus shifted from Nauvoo’s role in American westward expansion to the city’s place in Church history and particularly to the lives and beliefs of significant resident Church members. [46] Even when the Church’s westward movement was discussed, emphasis was placed on Joseph Smith’s preparations for the departure. [47] Obedient to his ecclesiastical leaders, Dr. Kimball shifted Nauvoo’s focus toward its missionary potential. Writing to President Spencer W. Kimball, Dr. Kimball summarized the new approach: “We keep foremost in mind that the basic purpose of the restoration is to proselyte, and therefore the Church and its doctrines are woven into the historic story, which brought the visitors to Nauvoo.” [48] Speaking to a Church News reporter, Dr. Kimball emphasized the city’s focus: “Every move in the restoration has been done with proselyting in mind.” [49]

Dr. Kimball’s instructions to his missionaries reflect the emphasis he placed on proselyting. To one missionary couple, Dr. Kimball wrote:

If you will put it all in a historical setting and yet tell it as history but tell it also as the principles of the Gospel, you will get the idea over to the people and they will understand it. It will not be like throwing “preaching” at them, but at the same time they will understand the message. . . . In this respect, you are still telling the story in terms of history, but at the same time you are satisfying the desire of the brethren to preach the Gosple [sic]. Keep in mind that there are many ways to approach the history of Nauvoo, but this gives you some idea of the great missionary tool that each home or shop really has! [50]

Dr. Kimball even modeled how to turn a presentation regarding Wilford Woodruff into a missionary opportunity:

I think we ought to take the people through each home or shop and then talk something of the man of the house and what “made him tick.”

By this, I mean, for example, that we would take people through the Wilford Woodruff home. We would explain the house and all that we wanted to and then say: “We are very sure that you would like to know something about Wilford Woodruff as a man and what his beliefs were, etc.” Then I would tell them a little bit about where he was raised, how he joined the Church, his admiration for the Prophet Joseph Smith and what his conversion meant. I would explain that he fully believed that there was a falling away from the truth and that now a restoration [was] made through the Prophet. And then I would mention something about his belief in the Book of Mormon and how he sustained the Prophet.

Then I would explain that:

“On your tour through Nauvoo, you will eventually come to the . . . former site of the temple of Nauvoo. This was built under severe persecution and at the time of the expulsion of the saints from this same area, they actually completed the temple before they had to leave. Wilford Woodruff was one of the men who with there [sic] own hands, helped to build that temple.

“It will be interesting to you also to know that it was the same Wilford Woodruff who dedicated the great temple in Salt Lake City. Now would you like to know something as to why the Mormons build temples?” [51]

Thus Dr. Kimball transformed a historical discussion of Wilford Woodruff into a teaching opportunity about temples.

Visitors responded to the message. One Illinois resident wrote of having toured Nauvoo many times. Especially moved by his most recent visit, however, he praised the new emphasis: “Through the years I have read and studied extensively concerning the history of old Nauvoo. I continue to do so avidly with special interest and emphasis upon its people, their aspirations, motivations, and ultimate anguished despair and decision to move elsewhere.” Touched by the story, the visitor continued, “The more I learn about these fascinating historical facts, the more impressed and involved I become. I am going to concentrate now upon Mormonism itself in order to better understand its tenets and its followers’ contributions to and benefits from their participation in it. I am especially impressed and intrigued with the zeal and purpose manifested so visibly by those with whom I have become acquainted.” [52]

Though the change in message was difficult, results like this pleased Dr. Kimball, who reported to the First Presidency, “Nauvoo has met and exceeded our greatest desires as an instrument to tell the story of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.” Noting that the way Nauvoo told “the American history of the westward expansion of this great country” had been “hailed as an unsurpassed eyewitness example” and that “the authenticity of the restoration work has been compared to that of Colonial Williamsburg for its impact and quality,” Dr. Kimball nevertheless concluded, “Proud as we are of these accomplishments, we are even more excited at the prospect of the number of people that are touched not only with history and the physical restoration, but also with the spiritual restoration of the gospel.” [53]

This emphasis on using Nauvoo for missionary purposes did not go unnoticed, however. A writer for the Chicago Tribune summarized his visit to Nauvoo, and specifically his experience in the visitors’ center itself: “Subject matter is about 50 per cent history and 50 per cent religion. The Mormons are active recruiters, as most Chicago householders know from the periodic visits of the polite, well-dressed young men from Utah. There is no pressure of any kind in the center tour, but you will come out knowing a lot about Joseph Smith and the principles of the religion he founded.” [54] In fact, the emphasis on Nauvoo as the City of Joseph was no more evident during this era than in the creation of the musical theatrical production of the same name, which has been performed regularly since 1971. The pageant’s author, R. Don Oscarson, summarized its missionary potential. “The show is designed for the non-member,” Oscarson noted. “It is low key; it doesn’t preach . . . yet it shows Joseph going into the grove to pray and presents all the principles of the gospel.” [55] The success of the pageant, coupled with ongoing restoration efforts, increased visitors to Nauvoo. Numbers grew from 154,782 visitors in 1970 to 671,065 visitors in 1981, with a spike of 855,204 visitors in 1978, the year the Relief Society Monument to Women was dedicated. [56]

Organizationally, the Nauvoo Mission itself has ebbed and flowed since its formation in 1971. In 1974, the mission was dissolved, with NRI reassuming control over the missionary work of senior couples and single missionary sisters. The mission reopened in 1985, with Lynn J. Thomsen as president. It closed again in 1987, only to reopen in 2000 under the direction of Richard K. Sager. [57] While the mission and its history have fluctuated, though, the Church’s missionary emphasis for Nauvoo and the influence of NRI have remained constant. In 1986, at the age of eighty-five and after twenty-four years of service as its president, J. LeRoy Kimball finally stepped down from leading NRI. Elder Loren C. Dunn, president of the Church’s North America Northeast Area, assumed the presidency of the board, with his counselors serving as vice president and secretary. Since then, NRI has been entirely headed by Church officials. [58]

As NRI moved into its post–J. LeRoy Kimball phase, Nauvoo’s purpose continued to transform. While significant projects—including a 1989 renovation of the Carthage Jail complex and Nauvoo Visitors Center, restoration of the historic Nauvoo cemetery, and construction of the Riser Boot and Shoemaker Shop and the Stoddard Tinsmith Shop—occurred during subsequent NRI administrations, the focus of Nauvoo continued to turn toward a missionary message. Speaking of these projects, Elder Dunn reflected, “The emphasis, of course, is to bring people in through the door of history. The history of the Church, properly told, can create great interest. And when you tell the story of Nauvoo, you tell the story of the Church.” [59] Further distancing the restoration from historical accuracy, representative rather than authentic log cabins and wooden buildings were erected throughout the 1990s to serve missionary needs. Most significantly, more than twenty modern brick residences were constructed in the historic district in 2002 to house temple missionaries. [60]

In 1989, NRI President Loren C. Dunn announced a significant change for Nauvoo’s future. “No further restoration is planned in the Nauvoo area,” Elder Dunn declared, effectively ending the building boom. “With the homes and shops the Church has restored over the years, plus the visitors centers at Nauvoo and Carthage,” Dunn noted, “there is enough of a flavor of the old city there now to give people a good idea of how it was. . . . After this year, Nauvoo Restoration, Inc., will continue to function, but in an operations and maintenance mode, rather than one of construction.” [61]

An Intersection for Missionary, History, and Temple Interests

In spite of the proselyting focus for the City of Joseph, Nauvoo continues to be a unique place of intersection for the Church’s missionary, history, and temple departments. Before his release as NRI president, Elder H. Burke Peterson wrote Elder L. Aldin Porter, executive director of the Church’s missionary department, seeking to clarify the site’s purpose, especially as it related to the member experience in Nauvoo. “As an Area Presidency and as the Officers and members of the Board of Directors of NRI,” Elder Peterson stressed, “we have been instructed very clearly that, different from other visitors centers, the visitors center at Nauvoo is not seen as, nor should it be set up as a visitors center the primary purpose of which is to generate referrals and provide proselyting opportunities. In fact, the First Presidency has reminded us of the sacred nature of the entire Nauvoo Restoration project.” Clarifying that purpose, Elder Peterson continued, “In the counsel we have received, we have come to understand that the destiny of Nauvoo is to become a sacred monument to the Prophet Joseph Smith and those stalwart, faithful Saints who suffered and sacrificed so much that we might have a fullness of the gospel. We do not perceive,” Elder Peterson continued, “the principal value of Nauvoo to be that of a proselyting tool, but rather, as a sacred, historical site where the fullness of the gospel was restored—a place where members of the Church may feel the spirit of the people who lived there and be strengthened in their desires, efforts, and convictions by an increased understanding and recognition of the faith, testimony, and dedication of the people who built this beautiful city.”

For nonmembers, Peterson continued, “another important value (though secondary to the principal value) is to have non-members who visit feel that same spirit and want to know what it was that made those people willing and able to survive the persecution they suffered, and to accomplish the things they did. As you know, we have altered somewhat the dialogue the missionaries use to encourage those visitors who do want to know more; and, we have done this without offending the real purpose for our being there.” [62] Clearly, missionary work has a place in Nauvoo, but it seems increasingly tempered by other Church interests for the City of Joseph.

Verbalizing these multiple interests, NRI officials summarized a threefold “mission and purpose for Nauvoo Restoration, Inc.” in 1993:

- It is to be kept as a monument or memorial to the Prophet Joseph Smith and those stalwart faithful saints who suffered and sacrificed so much that we might enjoy a fullness of the restored gospel. Nauvoo is a sacred place where the ordinances of the Temple were restored and as such makes it one of the most sacred locations in the history of our Church.

- It is to be maintained as a place where members of the Church can come and feel the spirit of those stalwart people who lived here and thus have their faith and testimony strengthened and gain in a desire to live the gospel as they learn more of the dedication and faith of those who founded Nauvoo.

- It is a place where non-members may come and learn of our pioneer ancestors and by feeling the sweet spirit found here, they will want to know more abut the things that inspired and gave courage and ability to those faithful saints who survived their persecution to accomplish all they did while in Nauvoo. [63]

The idea that Nauvoo be “kept as a monument or memorial” was nowhere more evident in the 1990s than at the site of the Prophet’s crowning project in Nauvoo—the temple itself. In 1993, NRI officials remarked on the state of the vacant temple lot, “Currently the Temple Site is probably in the poorest condition of any of our sites in Nauvoo, and it should in reality be our centerpiece.” Explaining their rationale, officials continued:

In all the structures, sites and holdings of NRI, we have nothing that was owned, or lived in by the Prophet. All of those sites belong to the RLDS. However, the real focus and purpose of Nauvoo is found in the Temple, thru the fullness of the gospel and the ordinances as provided in the Temple. It would seem to us that the Temple Site should in reality be the main focal point of all the restored work in Nauvoo, for it represents the greatest degree of sacrifice by the saints and was certainly the central purpose for Nauvoo. Every thing done in Nauvoo was to build the Temple in order to restore these sacred ordinances of salvation and exaltation. [64]

Because of its significance, the temple lot underwent a host of beautification projects during the 1990s. Ultimately, these set the stage for the most dramatic change in Nauvoo’s missionary message—President Gordon B. Hinckley’s 1999 announcement that the Church would rebuild the Nauvoo Temple. The temple’s completion in 2002 provided a prominent visible reminder of the Church’s competing interests in the city.

Today, Nauvoo is a missionary, history, and temple site for the Church. Missionary work, directed by the Illinois Nauvoo Mission, oversees the work of single-sister and senior-couple site missionaries. The Church’s historical department preserves and protects the restored structures themselves, influencing the historical message conveyed in each location. Finally, a temple presidency and the Church’s temple department oversee the sacred ordinance work conducted within the walls of the reconstructed Nauvoo Temple, aided by senior temple missionaries who serve the patrons. In a rural town as small as Nauvoo, departmental overlap certainly occurs on a regular basis.

The Nauvoo Temple, which provides a prominent visible reminder of the Church's competing interests in the city, as well as the fulfillment of Bryant S. Hinckley's dreams by his son Gordon B Hinckley. Courtesy of Brent R. Nordgren.

The Nauvoo Temple, which provides a prominent visible reminder of the Church's competing interests in the city, as well as the fulfillment of Bryant S. Hinckley's dreams by his son Gordon B Hinckley. Courtesy of Brent R. Nordgren.

Conclusion

Hundreds of thousands of visitors annually flock to this bend in the Mississippi River for many different reasons. Like Palmyra, Kirtland, Winter Quarters, and other sites sacred to the Restoration, the Church uses Nauvoo for a variety of purposes. For members, it is a place to connect to a shared sacred past, a site of hopes, history, sorrows, and sacrifice. With the construction of the temple, Nauvoo is also becoming a place for covenant renewal and service. The missionary history of Nauvoo, including its restoration, proselyting, and memorial phases, reflects these changing purposes. For nonmembers, Latter-day Saint purposes both coincide with and contradict their interests in this “Williamsburg of the Midwest.” As with any of its historic missionary sites, the Church understandably struggles at times to satisfy its varied audiences.

True to the Lord’s 1841 charge, the Church continues to try to make Nauvoo “a delightful habitation for man,” a “resting-place for the weary traveler” as he “contemplate[s] the glory of Zion” (D&C 124:60). At the same time, the Church also seeks to be sensitive to local interests for this Midwest farm town. The Church strives to follow another charge, which was directed to the Saints in Missouri in 1834: “Carefully gather together, as much in one region as can be, consistently with the feelings of the people” (D&C 105:24). By doing so, the Church hopes to receive the Lord’s blessing: “I will give unto you favor and grace in their eyes, that you may rest in peace and safety. . . . In this way you may find favor in the eyes of the people” (D&C 105:25–26). The tension of appeasing locals while fulfilling a charge to declare the restored gospel of Jesus Christ was a theme of Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo in the 1840s and today continues to be a theme of the Church and city he founded.

Notes

[1] Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833–1898 Typescript, vol. 3, 1846–1850, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 49.

[2] John Taylor, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1855–86), 23:61–62.

[3] Thomas H. Burton, “Visit to Nauvoo and Carthage,” Journal History of the Church, July 25, 1901, 7, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[4] F. M. Mortensen and George H. Smith, “Visit City of Nauvoo,” Journal History of the Church, July 24, 1905, 2.

[5] “Conference in Nauvoo, Illinois,” Journal History of the Church, October 3, 1905, 9.

[6] “Utah Mormons Visit Nauvoo,” Journal History of the Church, October 4, 1905, 10.

[7] “In Nauvoo,” Journal History of the Church, December 28, 1907, 1–2.

[8] Julia A. F. Lund, “Relief Society Monument Unveiled in Nauvoo,” Relief Society Magazine, September 1933, 511.

[9] Although the Carthage Jail was the first historic building purchased by the Church, leaders had acquired the pioneer cemetery at Mount Pisgah, Iowa, in 1888. See H. Dean Garrett, “Mount Pisgah,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 800.

[10] Bryant S. Hinckley, “The Nauvoo Memorial,” Improvement Era, August 1938, 511.

[11] Lisle G. Brown, “Nauvoo’s Temple Square,” BYU Studies 41, no. 4 (Fall 2002): 24.

[12] “Historic Nauvoo Buildings House Missionaries,” Journal History of the Church, November 7, 1953, 4.

[13] The Kimball home, the first structure “restored” in old Nauvoo, contains elements that are beyond the building’s 1840s simplicity. Restorations like this, with “nonperiod, overly elegant furnishings,” became a source of conflict for Nauvoo Restoration officials. See T. Edgar Lyon Jr., T. Edgar Lyon: A Teacher in Zion (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2002), 281.

[14] Dr. Kimball’s motivation for purchasing properties adjacent to the Heber C. Kimball home included protecting it from encroaching entrepreneurial interests in the area. For a discussion of this and other issues related to Nauvoo’s restoration, see Benjamin C. Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo: The Mormons and the Rise of Historical Archaeology in America (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 58–60. The author expresses sincere appreciation for Pykles’s thorough study, which lays the groundwork for much of this paper.

[15] “What is Nauvoo Restoration, Incorporated?” (Nauvoo, IL: Nauvoo Restoration, Inc., n.d.).

[16] “What is Nauvoo Restoration, Incorporated?”.

[17] Rowena J. Miller to J. Alan Blodgett, July 6, 1981, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files, Nauvoo, IL; see also Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 89.

[18] Harold P. Fabian, “Mr. Fabian’s Remarks at the Presidential Dinner,” April 20, 1965, cited in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 139–40.

[19] A. Hamer Reiser, cited in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 147–48.

[20] J. LeRoy Kimball, cited in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 143.

[21] Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 1–2.

[22] Dee F. Green, “Interior Partitions Found in Temple Basement,” Nauvoo Independent, August 30, 1962.

[23] “Report of Progress and Development by the President to the Board of Trustees of Nauvoo Restoration, Incorporated,” June 25, 1964, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files, 16–17.

[24] Todd Hamilton, “After 120 Years Old Nauvoo Restored,” International Harvester Farm Magazine (Summer 1966): 3.

[25] “The Era Asks about Nauvoo Restoration,” Improvement Era, July 1967, 16–17.

[26] “The Era Asks about Nauvoo Restoration,” 16–17.

[27] James Frederick, “Historic Mormon Town Comes to Life Again,” Des Moines Sunday Register, September 17, 1972, 12.

[28] “The Era Asks about Nauvoo Restoration,” 16.

[29] Lloyd Maffitt, “Nauvoo to Be Williamsburg of Midwest,” Hawk-Eye, March 4, 1969, 3.

[30] “Two Basic Principles for Guide Service,” Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[31] “Two Basic Principles for Guide Service,” Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[32] “Abandoned Mormon Village Reconstructs Its Busy Past,” Journal History of the Church, July 9, 1972.

[33] Rowena Miller to Rex Sohm, April 26, 1967, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[34] Donald V. Lents to the First Presidency and the Presiding Bishopric, October 4, 1961, Historic Properties, RG 26, fd. 191, Community of Christ Library-Archives, Independence, MO.

[35] “Rebuilding at Nauvoo,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, December 13, 1970, 6.

[36] James W. Moffitt, Oral History, interview by Jayson Edwards, October 2001, in Modern Perspectives on Nauvoo and the Mormons: Interviews with Long-Term Residents, ed. Larry E. Dahl and Don Norton (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2003), 180.

[37] Charles Kirchner, “Contemporary Planning in Nauvoo, Illinois,” March 20, 1970, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[38] David W. Knowles, Oral History, interview by Andrew Wahlstrom, September 28, 2001, in Modern Perspectives on Nauvoo and the Mormons, 109–10.

[39] Rowena J. Miller to J. Alan Blodgett, July 6, 1981, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[40] T. Edgar Lyon, quoted in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 152–53.

[41] Quoted in Lyon, T. Edgar Lyon, 280.

[42] Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 158–59; see also Rowena J. Miller to J. Alan Blodgett, July 6, 1981, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[43] A. Edwin Kendrew, “Remarks by A. Edwin Kendrew,” May 22, 1971, quoted in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 160.

[44] Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the Members and Board of Trustees on Nauvoo Restoration, Incorporated, May 22, 1971, 3, quoted in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 161.

[45] Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the Members and Board of Trustees on Nauvoo Restoration, Incorporated, May 22, 1971, 3, quoted in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 159.

[46] Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 165.

[47] Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 166.

[48] J. LeRoy Kimball to Spencer W. Kimball and others, January 7, 1974, quoted in Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 173.

[49] Gerry Avant, “Nauvoo’s Impact,” Church News, August 27, 1977.

[50] J. LeRoy Kimball to Missionary Couple, n.d., Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[51] J. LeRoy Kimball to Missionary Couple, n.d., Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files. This approach was not original to Dr. Kimball. Rather, it appears he patterned it from a letter sent by Mark E. Petersen to Delbert L. Stapley, summarizing a meeting between the three men. See Mark E. Petersen to Delbert L. Stapley, July 7, 1970, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files; see also Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 163–64.

[52] Richard E. Bright to Director, Visitors Information Center, October 13, 1982, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[53] J. LeRoy Kimball to President Spencer W. Kimball and Counselors, April 23, 1982, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[54] Jack Mabley, “Mormons of Nauvoo Did What They Had to Do,” Chicago Tribune, April 5, 1977, 4.

[55] Gerry Avant, “Play Beckons, ‘Walk My Quiet Roads,’” Church News, August 21, 1982, 10.

[56] “Nauvoo Restoration,” Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[57] Backmans and Singletons, “A Brief Chronology of Nauovo [sic] Restoration, Inc.,” Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[58] Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 185.

[59] R. Scott Lloyd, “Era of Restoration Ends in Nauvoo,” Church News, October 6, 1990.

[60] Pykles, Excavating Nauvoo, 188–89.

[61] “Church Dedicates Visitors Center Complex in Carthage,” June 27, 1989, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[62] H. Burke Peterson, Hartman Rector Jr., and Graham W. Doxey to L. Aldin Porter, June 29, 1993, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[63] “Nauvoo Temple Site Restoration,” October 8, 1993, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.

[64] “Nauvoo Temple Site Restoration,” October 8, 1993, Nauvoo Restoration Inc. corporate files.