The Nineteenth-Century Euro-American Mormon Missionary Model

Reid L. Neilson

Reid L. Neilson, "The Nineteenth-Century Euro-American Mormon Missionary Model," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 65–90.

Reid L. Neilson was managing director of the Church History Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this book was published.

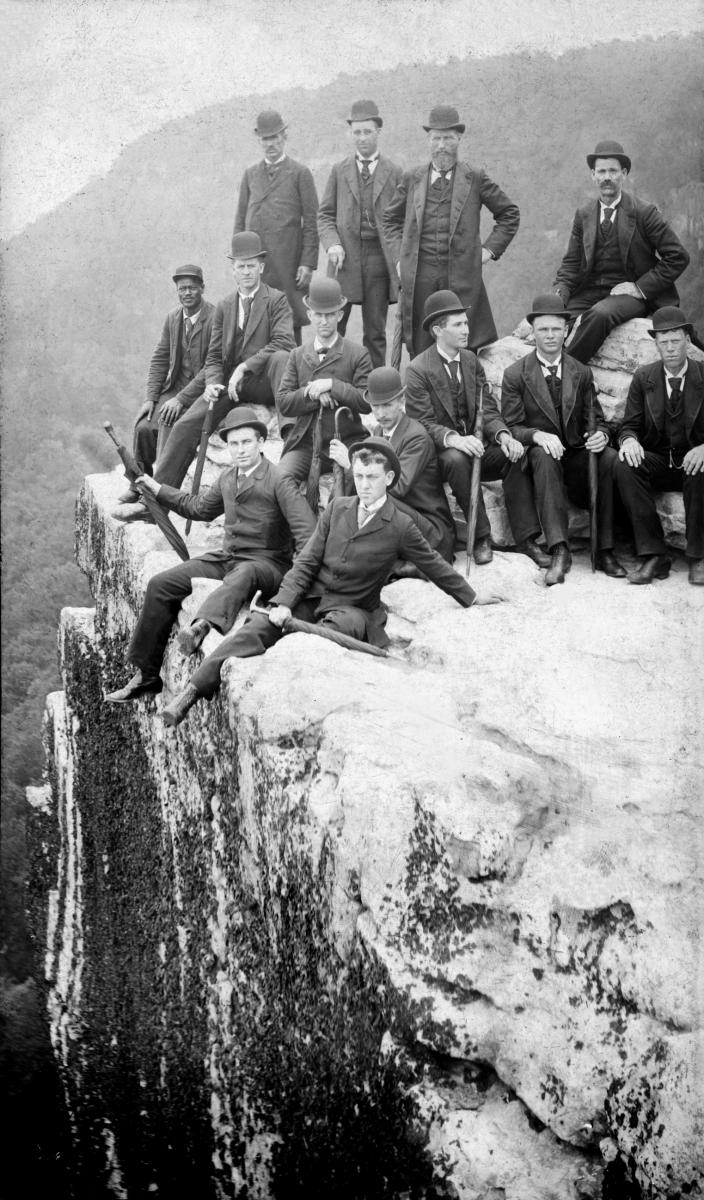

Elders from the Southern States Mission sitting on a cliff. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Elders from the Southern States Mission sitting on a cliff. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Nineteenth-century members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter cited as the Church) developed a unique method of evangelism, that I have tagged the “Euro-American Mormon missionary model.” As the label suggests, early LDS missionary work grew out of a Protestant North American and Western European historical context, not out of the “pagan” Asia-Pacific world. [1] The Mormon’s Anglocentric missionary approach enabled them to enjoy grand success in the United States and Canada as well as in Great Britain, Scandinavia, and parts of continental Europe. Their mode of evangelism and theological claims to primitive Christianity fired the imagination of prospective converts already saturated in biblical culture. The church that started with six members in 1830 ballooned to over 271,000 by 1900, largely the result of aggressive missionary work. [2] This entrenched pattern of evangelism, however, paradoxically hampered LDS missionary efforts in non-Christian, non-Western nations during the same era.

American Protestant and Mormon Missionary Enterprises

The American Protestant foreign missionary enterprise had its beginnings in outreach to the Native Americans during the colonial era. Several notable Puritan missionaries, like David Brainerd and John Eliot, worked with New England tribes to promulgate Christianity. But evangelism to Native Americans was not the driving force of the early colonists. “Protestants in the New World did not conceive of their errand into the wilderness primarily as the expression of missionary fervor,” historian Patricia R. Hill explains. “The main function of the church in Puritan eyes was not to convert the heathen without but to regulate the spiritual lives of the saints.” [3] Nevertheless, during the eighteenth century, the British Anglicans sent missionaries to America under the banner of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, and some Quakers and Moravians evangelized outside of Euro-American towns. American Protestants focused their energies on building up local congregations instead of evangelizing the heathens at home or abroad. It would not be until the First Great Awakening (ca. 1730–70) that the missionary impulse would play an increasing role in Protestant thought. [4]

Orson D. Romney reading with missionaries in New Zealand, 1912. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Orson D. Romney reading with missionaries in New Zealand, 1912. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The interdenominational New York Missionary Society, founded in 1796, was America’s first Protestant missionary organization. After the society’s founding, a growing number of likeminded groups worked among Native Americans. The Second Great Awakening (ca. 1790–1840) was responsible for the creation of numerous evangelical associations, including the American Bible Society, the American Colonization Society, and the American Tract Society. These and other antebellum voluntary missionary societies grew out of theologian Samuel Hopkins’s idea of disinterested benevolence, or the notion that one should seek to bless others through the Christian gospel not out of fear of divine punishment or out of a guilty conscience but from a desire to please Jesus Christ. Students at the Andover Theological Seminary were responsible for the genesis of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission in 1810, decades after other European powers had sent missionaries to the Pacific world. By the Civil War, American Protestants were evangelizing in the nations of South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, Latin America, East Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Catholic Europe. Initially, many Protestant denominations worked together in foreign missions until the splintering of missionary boards in the postbellum era. But all were driven by the sense of American Manifest Destiny, or the notion that American Christians were responsible not only for the salvation of North America but also for the entire world. [5]

Like many nineteenth-century American Christians, the Latter-day Saints believed that the resurrected Christ had commanded his disciples in the Old World to “teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” (Matthew 28:19). Although nearly two millennia had passed since the earliest Christians attempted to meet this obligation, their counterparts in the New World still sought to share the Christian gospel with every nation, kindred, and tongue. The Mormons, despite their poverty, persecution, and eventual displacement to North America’s Great Basin region, helped shoulder the ever-present burden of fulfilling the biblical Great Commission. [6] As theological restorationists, in the most literal sense, the Latter-day Saints attempted to recapitulate biblical history. Mormon missionaries saw themselves as walking in the footsteps of earlier evangelists like Paul and Timothy. [7]

Latter-day Saints shared much of the same Christian worldview as American Protestants. Millenarianism, for example, influenced the thought and decision making of LDS leaders and laity alike. [8] Historian Grant Underwood argues, “Millennialism is far more than simply believing that the millennium is near. It is a comprehensive way of looking at human history and an integrated system of salvation. It is a type of eschatology used to refer broadly to people’s ideas about the final events in individual human lives as well as the collective end of human history.” [9] Specifically, Underwood claims that Latter-day Saints were premillennialists who believed that Christ’s Second Coming would usher in the Millennium, as opposed to postmillennialists who believed that the Millennium would precede Christ’s return. He and other scholars refute the conventional wisdom that suggests that premillennialists were not as dedicated to evangelism as postmillennialists. These scholars make the case that premillennialists held their own when it came to missionary work. Underwood gestures to evangelist Dwight L. Moody, who stated that he “felt like working three times as hard” once he embraced premillennialism, and to missionary George Duffield, who challenged antebellum critics who mistakenly claimed that premillennialism hampered the intensity and urgency of the missionary spirit. [10] Like Moody, Duffield, and other millenarian Protestants, the Latter-day Saints engaged the world rather than retreating from it only to save what they could in the process. [11]

In the months leading up to the formal organization of the Church in April 1830, Joseph Smith claimed a number of revelations that signaled evangelism would soon play a major role in his new religious movement. In February 1829, for example, he received a revelation addressed specifically to his father, Joseph Smith Sr., calling him to preach the gospel (see Doctrine and Covenants 4). Over the next several years, Mormonism’s founding prophet dictated similar inspired callings for numerous members of his growing flock. It soon became clear that all Church members were responsible for spreading the news of the Restoration. Once they were converted, they were responsible to warn their neighbors (see Doctrine and Covenants 88). Latter-day Saints were promised great spiritual blessings, including eternal joy, if they fulfilled their missionary duties and helped save souls (see Doctrine and Covenants 18). As a result, members of the growing movement felt the need and desire to share what they believed to be the restitution of primitive Christianity. [12]

During the 1830s and 1840s, while the Latter-day Saints gathered and scattered throughout New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois, Smith continued to encourage evangelism. New converts, the products of missionary work themselves, embraced their missionary responsibilities and went forth on their own, sharing the good news with their family and friends, with no formal missionary training. Although some were called directly to the work by revelation, the vast majority simply opened their mouths and shared their message with anyone who would listen. During these early decades, men continued to engage in their own economic pursuits and occupations, since there was no paid clergy in Mormonism. But they took sabbaticals from their worldly responsibilities and devoted themselves to short preaching tours, relying on the financial generosity of others. These early missions usually lasted for several weeks but sometimes as long as a few months, depending on the time of year and the missionaries’ professional obligations. In his classic study of North American LDS missionary work, historian S. George Ellsworth labeled this early evangelism model the freelance missionary system. This corps of nonprofessional missionaries preached wherever they could get a hearing. They evangelized in both public and private spaces. Town squares and street corners, as well as barns and cabins, became the sites of Mormon preaching. Untrained by the Protestant divinity schools of the East Coast, they preached a homespun message, noteworthy for its simplicity. Mormon missionaries typically worked through their existing social networks, approaching family and friends, with whom they already had a tie and, therefore, a better chance of being successful. Nevertheless, these men, like representatives of other Christian faiths, endured the disinterest and often the antagonism of their audiences. Freelance missionaries were remarkably successful in antebellum America, Canada, and, increasingly after 1837, in Great Britain. [13]

As the years rolled by, Mormon men were increasingly called by Church leaders to serve specific missions beyond their own neighborhoods and kin. Joseph Smith assigned Apostles from his newly created Quorum of the Twelve to evangelize up and down the eastern seaboard and Great Britain. [14] With many of the Apostles abroad, by the end of the 1830s members of the Quorum of the Seventy assumed the duty of calling missionaries. Nevertheless, freelance missionaries continued to staff Mormon missionary fields into the 1840s. When the majority of the Apostles returned from Great Britain in July 1841, they assumed the Seventy’s responsibility of calling missionaries. From this point on, the number of formally called missionaries grew and the number of self-called freelance missionaries shrank. Even so, both systems of missionaries—freelance and appointed—continued through the Nauvoo, Illinois, period and through the martyrdom of Joseph Smith in 1844. By midcentury, over 1,500 Latter-day Saints had served full-time missions. [15]

The Euro-American Mormon Missionary Model

Elders serving in France, ca. 1937–38. Unlike those of other Christian faiths, early Latter-day Saint missionary efforts were focused on the peoples of the Western world. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Elders serving in France, ca. 1937–38. Unlike those of other Christian faiths, early Latter-day Saint missionary efforts were focused on the peoples of the Western world. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Like other Christian faiths that thrived in, or grew out of, the spiritual hothouse of antebellum America, Mormonism developed a unique approach to evangelism that enabled it to spread beyond its upstate New York origins: the Euro-American missionary model. Because early LDS evangelism emerged from a North American and Western European historical context, its missionary methods privileged the West over the East. During the nineteenth century, the Mormons focused their missionary energies on the peoples of the Christian, Western world. They believed that Christ’s original gospel had been lost through apostasy until Joseph Smith restored the primitive church in 1830. As a result, all non-Mormon Christians, perhaps even more than the non-Christian “heathens,” were in dire need of the message of Mormonism.

American evangelical Protestants, on the other hand, targeted primarily non-Christians living in non-Western lands. Notable exceptions included Native Americans, Hispanic and Asian immigrants, and the members of domestic religious groups they considered deviant, especially the Mormons in Utah. But these evangelistic endeavors generally fell under the rubric of “home,” rather than “foreign,” missions. [16] (The dichotomy of “foreign” and “home” missions did not exist in the Mormon worldview. All areas outside of Utah were considered simply the “mission field.”) Unlike the Latter-day Saints, American Protestant missionaries had vast experience proselytizing in the Eastern world. As a result, they too advanced their own missionary model, one quite distinct from that of their Mormon contemporaries. Scholars can learn a great deal by comparing the two groups’ missionary models, especially by contrasting their evangelistic practices, personal backgrounds, missionary training, financial arrangements, and human deployment.

Evangelistic practices. By the late nineteenth century, the American Protestant foreign missionary enterprise was reeling from internal debate over the propriety of various types of evangelistic practices. The discussion can be summed up by the phrase “Christ versus culture.” On the one hand, more conservative Protestants, led by Rufus Anderson and Henry Venn, fought to do away with English-language teaching to the natives and other forms of westernization. Anderson and Venn’s camp believed that missionaries were sent abroad to teach the Christian gospel, not to transform local cultures into Western enclaves. They were concerned that assigning missionaries to foreign lands with specific trades, such as teaching, medicine, or agriculture, undermined the true evangelical purpose. They were proponents of Christ only and resisted the liberal reconceptualization of foreign missions. Conservative Protestants also believed that pluralism and inclusivism were slippery slopes to unbelief. They worried about the lack of testimony of emerging fundamental Christian positions on Biblical inerrancy that mainline missionaries in Asia and their supporters at home seem to have jettisoned during their tenures in the Orient. [17]

More liberal American Protestants, on the other hand, advocated a reinterpretation of Christian evangelistic practices. They argued that Christianization went hand in hand with civilization and advanced a number of criticisms of mainline missionary work as part of their pluralistic agenda. For decades they argued against Anderson’s conception of Christian missionary work being centered solely on the dissemination of Christian theology. Early Puritan missionaries like David Brainerd, who provided schools and assisted with Native American farming, provided the model for this alternative approach. Liberals sought to improve both temporal and spiritual conditions in local places. In other words, they advocated culture, then Christ. Many liberal Protestants rejected traditional Christian exclusivism while laboring in East Asia; they were unable to reconcile the displacement of Asian religions with seemingly unwanted and unappreciated Christianity. Rather than abandoning their missions, however, liberal Protestants reconfigured their roles, emphasizing Christ the humanitarian over Christ the teacher. Emboldened by the social gospel, these Protestants viewed the nursing of bodies, the teaching of minds, and the filling of bellies as a crucial precursor to the healing of souls. [18]

In contrast to the variety of missionary approaches battling within American Protestantism, nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints focused their missionary practices on unadulterated evangelism, according to their understanding. They focused on preaching Christ, not advancing Western culture, especially not American culture, which they often viewed as the antithesis of their gospel message. [19] Mormon evangelistic practices centered on gospel preaching and teaching opportunities. The men spent much of their time tracting or canvassing neighborhoods and busy streets while handing out printed leaflets or other literature on Mormon subjects. They would either sell or loan the pamphlets to interested persons and then try to arrange a teaching meeting to discuss unique LDS doctrines. The missionaries also used local newspapers to their advantage, especially since the dailies were often the organs of anti-Mormon rhetoric. LDS writers penned editorials and explanatory essays to defend their cause and spread their message. They also announced preaching meetings through local tabloids. Mormon missionaries held public preaching meetings whenever and wherever they could. They even rented other Christian church buildings to hold large audiences. Some Sundays they showed up at Protestant services and were invited to preach by uninformed clergy. After sharing their message of apostasy and the Restoration, the Mormons were rarely invited back. In some cases, the missionaries arranged for spirited debates with other religious leaders to stir up excitement. [20] Unlike some Protestant missionary organizations, the Latter-day Saints did not typically offer educational or social welfare services in the mission field. [21]

Personal backgrounds. American Protestant missionaries were grounded in this world but were driven by an otherworldly spiritual cause. Missionary service was an optional exercise for Protestant men and women. Foreign missions were demanding undertakings that required incredible commitment and long-term fortitude. Mission boards carefully screened prospective applicants for deep spirituality and evidence of personal conversion. Candidates shared their powerful moments of conversions in their paper applications to demonstrate that they were qualified for the work. The applicants were also expected to feel a specific sense of evangelistic purpose. They needed to feel compelled to work beyond domestic ecclesiastical opportunities. The Protestant missionary model was based on self-selection: one felt called by God, not an organization. “The single most important factor that transformed the Christian worker into a foreign missionary was his conviction that there was a greater need for his services abroad,” historian Valentin H. Rabe explains. [22]

What were the personal backgrounds of these men and women? The greater part of male Protestant missionaries hailed from the smaller settlements of New England and upstate New York. Few came from urban areas and maritime regions; some missionary boards were actually skeptical of candidates from larger cities. By 1880, less than 20 percent of one missionary organization’s volunteers grew up west of New England. By the turn of the century, however, things were changing. Missionary volunteers were signing on across the United States, although a growing number called the Midwest home. Most were born and reared in America, with the only exception being foreign missionaries’ now-mature children who had been born in the mission field. The bulk still left little villages and towns when they embarked on their missionary adventures. They were mainly middle-class Americans who had access to higher education. Few enjoyed wealthy upbringings, and those who did were viewed with some suspicion. For the most part, the foreign missionary enterprise at the ground level was an egalitarian undertaking. The backgrounds of female Protestant missionaries were more standardized, at least among the American Board’s volunteers. The typical missionary was an unmarried daughter of a large family from the countryside whose chances for marriage were doubtful. She likely had training as a teacher or nurse and desired to use her talents in foreign lands in the service of Christ. [23] Historian Barbara Welter points out that these women were “filling a role in a field abandoned” by men and were “achieving prominence in an institution which was itself declining in prestige.” [24]

Quite the opposite of American Protestants, Latter-day Saints did not view evangelism as optional. Mormon men, and women beginning in 1898, were issued unsolicited short-term missionary assignments by Church leaders. Those who were “called” to the work were expected to fulfill the assignments regardless of their personal, financial, or physical conditions. They did not participate in the geographic selection or timing of their callings. During the 1850s, the Mormon missionary system became more routinized and institutionalized. Geographically isolated in Utah from other Americans, LDS leaders replaced the freelance missionary system with the more organized appointed missionary system. General authorities began calling missionaries over the pulpit during the Church’s semiannual general conferences held in April and October in Salt Lake City. Men were often surprised to hear their names called, but the vast majority responded willingly. A demographic snapshot helps us better understand the backgrounds of the LDS missionaries who served during the 1850s. Their ages ranged between twenty and forty-eight, with the average being thirty-five years old. Given their average age, it is no surprise that most of the men were married with children. About a quarter of these men had previously served at least one mission. Although there was no formally set mission length, they served on average for thirty months. Throughout the 1860s, Church leaders continued to call missionaries during general conference, which made the semiannual event a time of great excitement and anxiety for male Church members and their families. The average LDS missionary age increased to thirty-seven during this decade. But most of these men were serving missions for the first time. Male Church members increasingly served only one full-time mission during their lifetimes, a change from earlier times when many served multiple assignments. [25]

During the 1870s, male LDS missionaries continued to receive their assignments during general conference. The length of missionary tenure decreased dramatically to only fourteen months, or less than half the length of the previous decade, easing the burden on family members left at home. The average missionary age increased to forty. During the 1880s, male Latter-day Saints mercifully learned of their missionary assignments by unsolicited letter, rather than by the surprise call during general conference. These calls were issued by Apostles assisted by members of a missionary committee. The average age of the missionary dropped to thirty-five. Most were still married men with wives and children. Moreover, the mission length increased to twenty-four months. By the late nineteenth century, the majority of missionaries came from the ranks of second-generation Latter-day Saints living in Utah. Few had previous evangelizing experience. The length of a mission had been unofficially standardized at about twenty-four months. The age had also decreased to an average of thirty years old. Rather than self-selecting as freelance missionaries, being called to serve during general conference, or even just receiving an unsolicited letter in the mail like their predecessors, the missionaries of the 1890s were consulted about the possibility of serving a mission by their local ecclesiastical leaders before they were extended formal assignments. A growing number of single younger men were being called to shoulder the work of the Great Commission. But it would not be until 1898 that the first female Latter-day Saints were called as full-time missionaries, apart from serving with their husbands. [26]

Gordon B. Hinckley and Ormond S. Coulan during their missionary service in England, ca. 1933. Unlike American Protestant organizations, the Latter-day Saint Church did not consider evangelism as optional. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Gordon B. Hinckley and Ormond S. Coulan during their missionary service in England, ca. 1933. Unlike American Protestant organizations, the Latter-day Saint Church did not consider evangelism as optional. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Missionary training. Although most of the early luminaries of the Protestant foreign missionary enterprise were graduates of prestigious New England divinity schools and universities such as Yale, Princeton, and Williams, the majority of missionaries during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century had studied at lesser-known denominational colleges and Bible schools. Many were the product of the Student Volunteer Movement or like-minded groups eager to evangelize the world “in this generation.” Mission agencies continually received candidates from church-affiliated institutions of higher learning. By the early twentieth century, between 87 and 95 percent of Protestant missionaries received formal missionary training and religious education at these church colleges before departing for their fields of labor. Understanding these recruiting dynamics, mission boards strategically created and maintained excellent relations with these schools, including helping to fill their faculties and staffs with missionary-minded men and women. As a group these Protestant missionaries were highly educated, especially when compared to the larger American population: not even 1 percent of white males in America had college degrees at the time. [27] Yet the missionaries did not typically learn the requisite foreign languages until arriving in the field, knowing that they would have years or even the rest of their lives to master the local tongue.

While their professional Protestant contemporaries enjoyed formal and extensive missionary training, the amateur Mormon missionaries received informal and narrow preparation. During the nineteenth century, LDS leaders did not provide a training regimen to the thousands of missionaries they assigned around the world. Instead, they expected the elders to learn how to be missionaries as they evangelized. The men learned what they could from more experienced missionaries and asked about evangelism conditions from returning missionaries. Some men prepared informally for their callings by studying the scriptures, practicing preaching, and even learning the basics of their foreign language as they sailed across the oceans to their missions. Beginning in 1867, Church leaders offered more formal theological training through the reestablishment of the School of the Prophets in Salt Lake City. Joseph Smith had arranged this education program in Kirtland, Ohio, and Nauvoo, Illinois, to help train new Church leaders and future missionaries. These classes quickly spread throughout Utah, where male members gathered weekly to study Mormon doctrine and discuss Church government and administration. Simple preparation for evangelism was also offered, but it never was the main attraction. Brigham Young discontinued the classes in the fall of 1872. Thereafter, missionaries received informal training through the Church’s auxiliary organizations, including Sunday Schools and the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association. Despite these educational opportunities, the Church’s mission presidents bemoaned the lack of training their elders received before arriving in the mission field. Few of the missionaries had any higher education, in stark contrast to Protestant missionaries. [28]

The Mormon elders received most of their training when they reached their mission fields. They learned how to evangelize by watching other missionaries, especially more senior companions and mission leaders. But in some missions, the elders did not always evangelize in pairs, stunting their learning curve. Some studied foreign languages the same way. The elders who lacked language skills were sometimes sent to live with member families who helped them learn the language. Ideally, Church leaders paired prospective elders and their language skills, if any, with specific mission fields. Danish-speaking missionaries were generally assigned to Denmark, their Swedish-speaking counterparts were usually sent to Sweden, and so on. Due to the massive immigration to Utah of tens of thousands of European converts, the languages of Western Europe did not prove a stumbling block to the Mormon missionary program. By the late nineteenth century, however, the number of prospective missionaries with native language skills decreased in tandem with the plummeting European immigration. Aware of the problem, Church leaders encouraged immigrant converts to teach their children (who often would be future missionaries themselves) their native languages. Nevertheless, LDS leaders did not offer formal missionary training until 1899, when they provided classes at several of the Church’s educational academies. And these classes focused more on gospel study and the acquisition of social graces and missionary methods than on language training. This haphazard preparation paled in comparison to the missionary schooling of their Protestant contemporaries at divinity schools and missionary colleges. The Church did not offer foreign language classes to its missionaries until after World War II. [29]

Financial arrangements. The majority of American Protestant missionaries were lifetime, salaried professionals. They viewed their calling to the work of evangelism as both a spiritual avocation and temporal vocation. Willing to sacrifice lives of potential ease back home, these intrepid men and women left America for their mission fields, where they would make their long-term homes. Since they were devoted to full-time evangelism, whether by the teaching of Christ or the advancement of Western culture, they relied on the financial generosity of mission boards and Christian organizations back in America for their support. As the Protestant foreign missionary enterprise swelled in the late nineteenth century, fundraising became a major task of domestic sponsor organizations. Protestant leaders encouraged their congregations and constituencies to give generously to provide financial assistance to their brothers and sisters serving abroad. Like most fundraising operations, however, the bulk of the contributions came from a committed few. In time, women contributed the majority of funds to mission boards. During the heyday of the foreign missionary enterprise, men reasserted themselves as key financial backers. In a bid to sustain the growing number of student volunteer missionaries, Luther D. Wishard helped launch the Forward Movement. He and his staff encouraged Protestant businessmen to give of their wealth for the greater good of missions. The Laymen’s Missionary Movement was another successful, yet short-lived, Protestant attempt to harness the enthusiasm and funds of successful businessmen, and later businesswomen, for the cause of foreign missions. By the early twentieth century, Americans had overtaken their British counterparts as the most prolific Protestant mission fundraisers. [30]

Unlike the full-time, salaried professional Protestant missionaries, the Mormon elders financed most of their nineteenth-century missions by relying on the New Testament model of traveling without purse or scrip, meaning evangelizing without cash or personal property (see Matthew 10:10; Luke 10:4). They went beyond the “extremism” of Hudson Taylor and relied entirely on those they met daily in their mission fields. Joseph Smith claimed several revelations encouraging the reestablishment of this practice (see D&C 24:18; 84:78). His successor, Brigham Young, was likewise a proponent of this financial arrangement, having served numerous missions to North America and Great Britain relying on the financial generosity of others. During the mid-1800s, a majority of Mormon missionaries were married, requiring the monetary maintenance of their families left behind. Given the economic circumstances in Utah at the time, supporting missionaries required great sacrifices of the missionaries’ wives and children. Although the men were expected to leave their families for several years in the best financial shape possible, many of these families had to rely on the contributions of fellow Church members for their survival. Local Church leaders were responsible for making sure these missionary families had funds sufficient for their needs. Church leaders created a short-lived Mission Fund in 1860 to help pay for these expenses. Latter-day Saints were encouraged to donate money, food, goods, and clothing for these temporarily fatherless families. In subsequent decades, Church members cultivated missionary gardens and farms to feed these dependents. By the late nineteenth century, however, unmarried young men were displacing married older men as the Church’s missionary force, so the need to take care of missionary families diminished. [31]

Mormon missionaries traveled domestically and internationally without purse or scrip for much of the nineteenth century. Those traveling abroad often sold their teams and wagons to help pay for their ship passage. Some of the elders also helped defray the cost of their sailing voyages by working odd jobs onboard ship. When they landed in their mission fields, they relied on the locals, both Church members and those of other faiths, to support their evangelism efforts. By the late 1860s, however, many Mormon missionaries were also benefiting from funds being sent from home. This helped ease the burden on local Church members, but some Church leaders were concerned that the missionaries might lose their humility and reliance on the Lord if they moved away from traveling without purse or scrip. By the late nineteenth century, the financial arrangements for the Mormon missionary system were a blend of local charity and family and Church support. Some missions, such as those in Switzerland and Germany, had vagrancy laws that kept the elders from relying on community contributions. [32]

Human deployment. American Protestants evangelized almost exclusively in non-Christian, non-Western nations. The editors of a turn-of-the-century missionary encyclopedia made it clear what constituted a foreign mission: “All Christendom is home to the Christian. To him the non-Christian lands, alone, are foreign lands.” Protestants made exceptions, however, for Protestant evangelism efforts in Roman Catholic-dominated countries and for missionary fields in North and South America where non-Christians, or “pagans,” exercised influence, such as parts of Canada and Alaska. [33] The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, America’s largest Protestant missionary organization, initially deployed its missionaries to South Asia and the Near East. By the end of the Age of Jackson, however, the American Board oversaw major evangelism campaigns in India, the Sandwich Islands, and the Near East, as well as minor missions in Southeast Asia, Africa, and China. But only the Near East and India remained the board’s star missionary fields by mid-century, while the Sandwich Islands, Africa, and China were given lower priority in terms of human and financial capital. Between 1812 and 1860, the American Board deployed 268 missionaries (out of 841 total) to the Near East (31.9 percent), 218 to India-Ceylon (25.9 percent), 170 to Hawaii and Micronesia (20.2 percent), 99 to East Asia (11.8 percent), and 86 to Africa (10.2 percent). [34]

After the Civil War, however, other American Protestant missionary boards increased their foreign evangelism efforts in East Asia, especially in China and Japan, the latter of which was finally opened to Christian missionaries in 1873. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, these East Asian nations, together with Korea, were the greatest beneficiaries of the American Protestant foreign missionary enterprise. [35] Between 1890 and 1915, the number of missionaries laboring in China, Japan, and Korea as a region skyrocketed by 900 percent. Other foreign missions around the world grew exponentially during the same time period, due in large part to the rise of the Student Volunteer Movement. Moreover, by 1915, 80 percent of American Protestants evangelizing abroad were clustered around the Mediterranean and massed in East Asia. It would not be until the second half of the twentieth century that their ranks would shift to Africa, Latin America, and even Christian Europe. [36]

The global deployment of Mormon missionaries was almost the exact opposite of the deployment of Protestants during the nineteenth century. Unlike the Protestants, Latter-day Saints focused their resources on the Christian, Western world. In theory, Mormonism was supposed to be a global religious tradition, a message for all. [37] In reality, its missionary program spread unevenly around the world. Much of the lopsided nineteenth-century human deployment was due to LDS racial, theological, and logistical concerns. [38] Between 1830 and 1899, Mormon general authorities called and set apart over twelve thousand full-time missionaries. Specifically, they assigned 6,444 (53.2 percent) Church members to evangelize throughout the United States and Canada and designated 4,798 (39.6 percent) Church members to evangelize in Europe, especially in Great Britain and Scandinavia. Mormon authorities sent the remaining 803 (6.6 percent) elders and sisters to the Pacific Basin Frontier, which includes Asia. But they assigned only twenty-seven (less than 1 percent) elders to Asian nations during the same period. Not a single LDS missionary evangelized in Japan before 1901. In short, they allocated an eye-popping 93 percent of their missionaries to the Atlantic world during the nineteenth century. [39]

The nineteenth-century Euro-American Mormon missionary model differed in important ways from the American Protestant missionary approach (see table 1). First, the Latter-day Saints focused on preaching Christ rather than exporting Western culture, regardless of the latter’s benefits. Unlike the Protestants who operated schools, hospitals, and churches, the Mormons tracted, held preaching meetings, engaged in intra-Christian debates, and contacted prospective converts on the streets. Second, Mormon missionaries, especially by the late nineteenth century, came from quite homogeneous backgrounds. The majority of missionaries were living in Utah when they received their mission calls, and most had no formal schooling beyond secondary education. American Protestants, on the other hand, hailed from across the Northeast and Midwest, representing numerous denominations. While LDS women did not formally evangelize until 1898, Protestant women constituted a major force within the foreign missionary enterprise. Third, the LDS elders were typically sent on their missions with little, if any, missionary training. While some attended theological classes before departing, most learned how to be missionaries once they arrived in their fields, in intensive on-the-job training. In contrast, most Protestant men and women enjoyed the benefits of higher education. Nearly all received formal missionary training through their mission boards before leaving the country. Fourth, Mormon missionaries were short-timers in their fields of labor, usually staying about two years before returning to their prior vocations. For much of the nineteenth century they traveled without purse or scrip. These amateurs and their families eventually had to pay much of the cost of their voluntary missionary service. On the other hand, their Protestant counterparts often committed the balance of their lives to further the cause of Christ. These professionals were financed through mission board fundraising activities back in America. Fifth, the vast majority of Latter-day Saints labored in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Scandinavia, all Christian nations. Conversely, American Protestants served the peoples of the Levant, South Asia, Africa, and East Asia, who knew little, if anything, of Christ.

Table 1. Comparison of the Mormon and American Protestant Missionary Models

| Component | Mormons | American Protestants |

| Evangelistic practices | Christ, not culture | Christ and culture |

| Personal backgrounds | Homogeneous | Heterogeneous |

| Missionary training | Informal, narrow | Formal, extensive |

| Financial arrangements | Short-time, volunteer amateurs | Lifetime, salaried professionals |

| Human deployment | Christian, Western world | Non-Christian, non-Western world |

Mormon Evangelization

To truly appreciate the development and the distinctive features of the nineteenth-century Mormon missionary model (evangelistic practices, personal backgrounds, missionary training, financial arrangements, and human deployment), it is helpful to compare them with the American Protestant evangelism experience. In summary, the LDS missionaries believed that missionary practices necessarily centered on Christ, not culture. [40] Their Protestant counterparts were split into various factions, some arguing for Christ and others arguing for culture as the heart of their missionary work. The Mormons came from homogeneous personal backgrounds, while the Protestants emerged from more heterogeneous circumstances. Missionaries from Utah received informal missionary training, whereas evangelists from various Protestant missionary boards benefited from formal preparation. The Latter-day Saints evangelized as short-time, volunteer amateurs alongside their lifetime, salaried professional Protestants. Lastly, Mormon elders almost always evangelized in North America and Western Europe. American Protestants, in contrast, labored in non-Christian, non-Western countries. While there are exceptions to any model (in this case, nuances in every mission and era), this typological comparison highlights how differently the Mormons approached evangelism in the nineteenth century.

Finally, there is no question that the nineteenth-century Mormon evangelism approach was geared toward the conversion of other Euro-Americans. Nor is there any doubt that they were incredibly successful evangelizers in the North Atlantic world as a result. [41] Nevertheless, their emphasis on converting other Euro-Americans, at the expense of Asians, Africans, and Latinos, had an unintended consequence: Mormons never learned how to rework their approach to non-Christian, non-Western audiences. During the nineteenth century, Mormons seemed content to impose their traditional missionary model, giving little thought to what we now call inculturation. It would not be until after World War II, and the true beginnings of Mormon globalization, that LDS leaders and missionaries would substantially retool their missionary model for their varied international investigators.

Notes

[1] I use the term “pagan” consciously to describe how the Euro-American Mormons viewed the inhabitants of Asia during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For example, see Alma O. Taylor, “Japan, the Ideal Mission Field,” Improvement Era, July 1910, 779–85.

[2] Deseret Morning News 2004 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2004), 580–81.

[3] Patricia R. Hill, “The Missionary Enterprise,” in Encyclopedia of the American Religious Experience: Studies of Traditions and Movements, ed. Peter Williams and Charles Lippy (New York: Scribner, 1988), 1683.

[4] Hill, “The Missionary Enterprise,” 1683; and William R. Hutchison, Errand to the World: American Protestant Thought and Foreign Missions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 15–42.

[5] Hill, “The Missionary Enterprise,” 1683–84; and Hutchison, Errand to the World, 43–61; see also David W. Kling, “The New Divinity and the Origins of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions,” in North American Foreign Mission, 1810–1914: Theology, Theory, and Policy, ed. Wilbert R. Shenk (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2004), 11–38; and Clifton J. Phillips, Protestant America and the Pagan World: The First Half Century of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1810–1860 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969).

[6] Jan Shipps, Sojourner in the Promised Land: Forty Years Among the Mormons (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 258–60.

[7] Jan Shipps, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 54–58.

[8] Richard Lee Rogers, “‘A Bright and New Constellation’: Millennial Narratives and the Origins of American Foreign Missions,” in North American Foreign Mission, 39–60.

[9] Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 2.

[10] As quoted in Underwood, Millenarian World, 7.

[11] Gary Shepherd and Gordon Shepherd, A Kingdom Transformed: Themes in the Development of Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1984), 45.

[12] William E. Hughes, “A Profile of the Missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1849–1900” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1986), 1–2; see also Rex Thomas Price Jr., “The Mormon Missionary of the Nineteenth Century” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1991).

[13] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 2–3; and Rodney Stark, “The Basis of Mormon Success: A Theoretical Application,” in Mormons and Mormonism: An Introduction to an American World Religion, ed. Eric A. Eliason (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 215–20. See also S. George Ellsworth, chap. 5 in “A History of Mormon Missions in the United States and Canada, 1830–1860” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1951); and James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men with a Mission: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles, 1837–1841 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992).

[14] The British Mission soon became the Church’s largest growth center. At one point there were more Church members in Western Europe than in North America.

[15] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 5–7.

[16] See Nicholas Griffiths and Fernando Cervantes, eds., Spiritual Encounters: Interactions Between Christianity and Native Religions in Colonial America (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999); Susan M. Yohn, A Contest of Faiths: Missionary Women and Pluralism in the American Southwest (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995); Daniel Liestman, “‘To Win Redeemed Souls From Heathen Darkness’: Protestant Response to the Chinese of the Pacific Northwest in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Western Historical Quarterly 24, no. 2 (May 1993): 179–201; and Jana K. Riess, “Heathen in Our Fair Land: Anti-Polygamy and Protestant Women’s Missions to Utah, 1869–1910” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2000). For an overview of the home missionary movement, see Robert T. Handy, We Witness Together: A History of Cooperative Home Missions (New York: Friendship Press, 1957).

[17] Hutchison, Errand to the World, 138–45.

[18] Hill, “The Missionary Enterprise,” 1685; Shepherd and Shepherd, Mormon Passage, 7; and Hutchison, Errand to the World, 102–11. See also Lian Xi, The Conversion of Missionaries: Liberalism in American Protestant Missions in China, 1907–1932 (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997); and Grant Wacker, “Second Thoughts on the Great Commission: Liberal Protestants and Foreign Missions, 1890–1940,” in Earthen Vessels: American Evangelicals and Foreign Missions, 1880–1980, ed. Joel A. Carpenter and Wilbert R. Shenk (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1990), 281–300.

[19] Laurie Maffly-Kipp, “Looking West: Mormonism and the Pacific World,” Journal of Mormon History 26, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 47–51. See also M. Guy Bishop, “Waging Holy War: Mormon-Congregationalist Conflict in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Hawaii,” Journal of Mormon History 17 (1991): 110–19.

[20] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 88–99; see also David J. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Pamphleteering” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1982).

[21] An important exception to this occurred in the Pacific world, where the Mormons organized schools and helped improve agricultural techniques among the Polynesians. See R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaii (Laie: Institute for Polynesian Studies, 1989), 29–31. In these isolated cases, the LDS civilizing impulse seems to have stemmed from two Mormon beliefs. First, Mormons felt it necessary to provide a non-Protestant educational alternative for the children of their converts for retention purposes. Second, they believed that many of the Pacific Islanders were actually the descendents of Book of Mormon peoples to whom they had a theological obligation to both spiritually and temporally uplift. See Norman Douglas, “The Sons of Lehi and the Seed of Cain: Racial Myths in Mormon Scripture and their Relevance to the Pacific Islands,” Journal of Religious History 8, no. 1 (June 1974): 90–104; and Maffly-Kipp, “Looking West,” 57–61.

[22] Valentin H. Rabe, “Evangelical Logistics: Mission Support and Resources to 1920,” in The Missionary Enterprise in China and America, ed. John K. Fairbank (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974), 75, 77–79.

[23] Rabe, “Evangelical Logistics,” 75–77; see also Patricia Grimshaw, Paths of Duty: American Missionary Wives in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1989); and Jane Hunter, The Gospel of Gentility: American Women Missionaries in Turn-of-the-Century China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984).

[24] Barbara Welter, “‘She Hath Done What She Could’: Protestant Women’s Missionary Careers in Nineteenth-Century America,” American Quarterly 30, no. 5 (Winter 1978): 638.

[25] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 7–8, 176–78.

[26] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 179–81. For a history of LDS women missionaries, see Calvin S. Kunz, “A History of Female Missionary Activity in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1898” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1976); and Carol Cornwall Madsen, “Mormon Missionary Wives in Nineteenth Century Polynesia,” Journal of Mormon History 13 (1986–87): 61–85.

[27] Rabe, “Evangelical Logistics,” 74–75.

[28] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 37–41.

[29] Reid L. Neilson, “Introduction: Laboring in the Old Country,” in Legacy of Sacrifice: Missionaries to Scandinavia, 1872–1894, ed. Susan Easton Black, Shauna C. Anderson, and Ruth Ellen Maness (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), xiii–xix; and Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 41–46.

[30] Rabe, “Evangelical Logistics,” 81–89; and David G. Dawson, “Funding Mission in the Early Twentieth Century,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 24 (October 2000): 155–58; see also Richard S. Wierenga, “The Financial Support of Foreign Missions,” in Lengthened Cords: A Book about World Missions in Honor of Henry J. Evenhouse, ed. Roger S. Greenway (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1975), 343–46. For a study on how foreign missions and fundraising impacted Protestant congregations back in America, see Lawrence D. Kessler, “‘Hands Across the Sea’: Foreign Missions and Home Support,” in United States Attitudes and Policies Toward China: The Impact of American Missionaries, ed. Patricia Neils (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1990), 78–96.

[31] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 49–56.

[32] Hughes, “Profile of the Missionaries,” 57–70; see also Richard L. Jensen, “Without Purse or Scrip?: Financing Latter-day Saint Missionary Work in Europe in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Mormon History 12 (1985): 3–14; and Jessie L. Embry, “Without Purse or Scrip,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 29, no. 3 (Fall 1996): 77–93.

[33] Henry Otis Dwight, H. Allen Tupper, and Edwin Munsell Bliss, The Encyclopedia of Missions, 2nd ed. (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1904), 835, 838–45.

[34] Field, “Near East Notes and Far East Queries,” in The Missionary Enterprise in China and America, 31–33.

[35] Field, “Near East Notes and Far East Queries,” 33–37.

[36] W. Richie Hogg, “The Role of American Protestantism in World Mission,” in American Missions in Bicentennial Perspective, ed. R. Pierce Beaver (South Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1977), 376–77.

[37] Leonard J. Arrington, “Historical Development of International Mormonism,” Religious Studies and Theology 7 (January 1987): 9.

[38] Armand L. Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois, 2003), 1–2; see also Armand L. Mauss, “In Search of Ephraim: Traditional Mormon Conceptions of Lineage and Race,” Journal of Mormon History 25, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 131–73; and Douglas, “The Sons of Lehi and the Seed of Cain,” 90–104.

[39] Gordon Ivor Irving, Numerical Strength and Geographical Distribution of the LDS Missionary Force, 1830–1974 (Salt Lake City: Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1975), 9–15.

[40] Historian William R. Hutchison framed missionary history in terms of these two goals. See Hutchison, “Christ, Not Culture,” in Errand to the World, 62–90.

[41] Deseret Morning News 2004 Church Almanac, 580–81.