Heather M. Seferovich, "Hospitality and Hostility: Missionary Work in the American South, 1875–98," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 317–40.

Heather M. Seferovich was curator at the Education in Zion Gallery at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

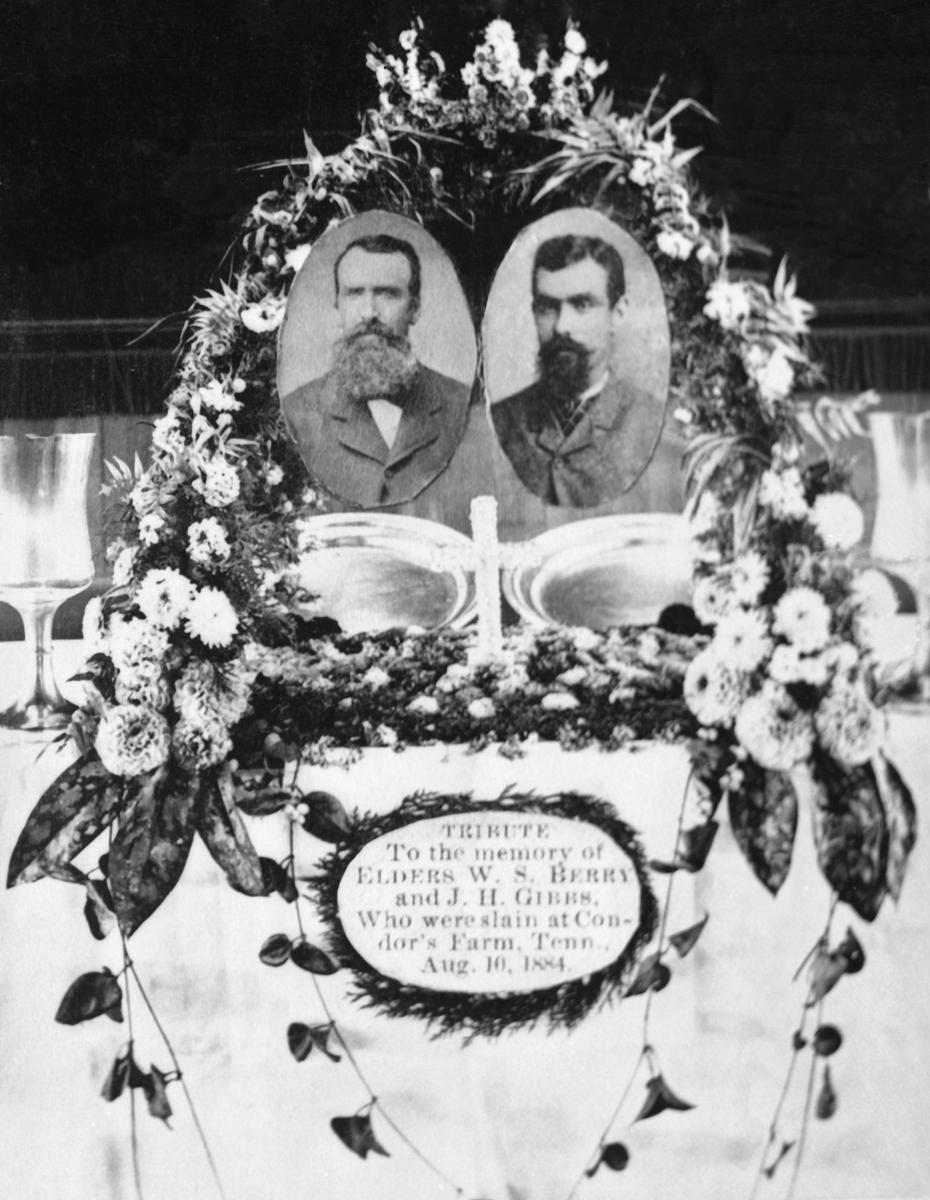

Tribute to Elders William S. Berry and John H. Gibbs, who died at the hands of a mob August 10, 1884. William Berry and John Gibbs were two of five missionaries in the Southern States Mission who were martyred between 1879 and 1898. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Tribute to Elders William S. Berry and John H. Gibbs, who died at the hands of a mob August 10, 1884. William Berry and John Gibbs were two of five missionaries in the Southern States Mission who were martyred between 1879 and 1898. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Missionary activity has been a staple feature of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) since its organization in 1830. The American South in particular was a significant region for LDS missionary work in the nineteenth century. The region has contributed a handful of influential converts who have been disproportionately represented in Mormon history. [1] Before the Civil War, the group known as the Mississippi Saints [2] and men such as Abraham O. Smoot, Henry G. Boyle, and Thomas E. Ricks were among those Southerners the elders converted. Furthermore, the South has been an important training ground for future Church leaders. Among those Southern States Mission (SSM) elders who have risen to high positions of ecclesiastical and public leadership have been Willard Washington Bean, Charles A. Callis, Rudger Clawson, Matthias F. Cowley, Andrew Jenson, J. Golden Kimball, Karl G. Maeser, John Hamilton Morgan, James H. Moyle, LeGrand Richards, B. H. Roberts, George Albert Smith, William Spry, Hosea F. Stout, George Teasdale, and Guy C. Wilson.

Southerners had not fully recovered from the turmoil of the Civil War and Reconstruction when Church leaders formally established the SSM in 1875. During and after this time, some Southerners, particularly in rural areas, acted xenophobically, disliking those they considered to be foreigners and sometimes even persecuting them; others tended to distrust foreigners but still treated them cordially. Many Southerners greeted Mormon missionaries, mostly westerners whom they saw as “spiritual carpetbaggers,” [3] with derision and hostility.

Throughout the late nineteenth century, missionaries serving in the South encountered every situation imaginable in their travels. In spite of the abundant hospitality extended to missionaries by the majority of Southerners, a small minority persecuted the elders. This persecution occasionally escalated to whipping and, in a few tragic instances, even included murder. As a result, the SSM swiftly acquired a reputation among Church members in the Great Basin for violence. Nearly all missionaries who served in the late nineteenth-century South noted Southerners’ polar nature: there were those who were friendly, who would share their last crumb of bread, and who would risk their lives defending the elders from their zealous neighbors; and there were those who were hostile, who acted as predators, and who actively persecuted them. Mormon elders received extraordinary kindness, apathetic indifference, and reprehensible brutality—each in varying degrees. The American South was both a hospitable and, occasionally, a hostile host to LDS missionaries, and honor dictated both of these responses.

Honor

As historian Bertram Wyatt-Brown has so carefully argued, Southern society was largely based on the ethical system of honor and shame. Honor often equated with reputation, particularly but not exclusively male reputation, in the community and among others who were in competition with each other. Thus it was honorable to offer shelter and food to a traveler because it connoted the power to command resources. While one’s first obligation was to family, strangers with references or a prepossessing appearance were usually welcomed. Those without such advantages were often turned away, particularly if they appeared to be beggars. At the same time, the South was characteristically more violent than the rest of the country because white Southern males felt honor-bound to defend against threats to their community. Failure to do so meant the breakdown of the social order and the loss of status and honor. [4]

Wyatt-Brown further explains how honor dictated the Southern temperament and how citizens responded to those in society they deemed to be malefactors. Southern honor was concerned with reputations, social status, respect, and loyalty. If any of these qualities were questioned, compromised, or violated, honor necessitated action, either to right the wrong or to restore the outward appearance of one’s honorable place and face. “The ethic of honor was designed to prevent unjustified violence, unpredictability, and anarchy. Occasionally it led to that very nightmare.” [5] Apparently it was this sense of honor that led some Southerners to harbor (that is, command resources [6]) as well as to harass (that is, defend against perceived threats from) Mormon missionaries.

Folklore has celebrated Southern violence almost as much as it has Southern hospitality. The need to fight appears to have been engraved into the region’s character. Southern violence seems to have flourished for two main reasons: honor and weak or minimal law enforcement. Because some Southerners paid little attention to formal laws—or distrusted them altogether—vigilantism thrived, particularly in the last half of the nineteenth century. [7] Notions of honor only compounded the threat of vigilantism. Reputations, social status, respect, and loyalty were inextricably linked to honor. Honor underscored both aggressiveness and competitiveness. Furthermore, the Southern hierarchical culture fueled a society based on honor. Wyatt-Brown employs literary works, as well as ancient history, to create a definition of honor—a tacit societal understanding, independent of time and place, that involves notions of self-worth, both publicly and privately. A perceptive writer once explained, “A [Southern] man’s sense of honor appears to have been just as impulsive as his trigger finger.” [8]

Within such an environment, feelings of fear and prejudice, or perceptions of lost power or honor, often ignited individual and group violence. These basic ingredients seemed to have been present in most cases of lynching and other atrocities, including those perpetrated against LDS missionaries. Of course, the persecution endured by Mormon elders is on a vastly smaller scale than the suffering endured by African Americans in the South.

Beginning of the Southern States Mission

The Southern States Mission was formally organized by Brigham Young during the October 1875 general conference. Eight men—Henry G. Boyle, George Teasdale, D. P. Rainey, Joseph Standing, John Morgan, John D. H. McCallister, David H. Perry, and John Winder—were assigned to fulfill missions to the South. By the next summer, the mission encompassed six states: Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia. [9]

From the Church’s inception in 1830, its missionaries generally followed the ancient Apostles’ injunction from the New Testament of traveling without purse or scrip (see Matthew 10:9–10; Luke 6:8). Thus nineteenth-century Mormon missionaries believed they were to depend upon God’s mercy and the generosity of the people they encountered for food and lodging. The Church’s modern revelation in the Doctrine and Covenants endorsed the practice of the ancient Apostles and commanded contemporary elders to follow their example (see D&C 24:18; 84:77–78, 86). Defending this traveling method, mission president J. Golden Kimball once remarked, “Our mode of preaching the Gospel came from the Lord, and who dare be so presumptuous as to question His wisdom?” [10] Fortunately for those assigned to the SSM, honor worked in their favor for this mode of traveling because many Southerners proved to be hospitable hosts.

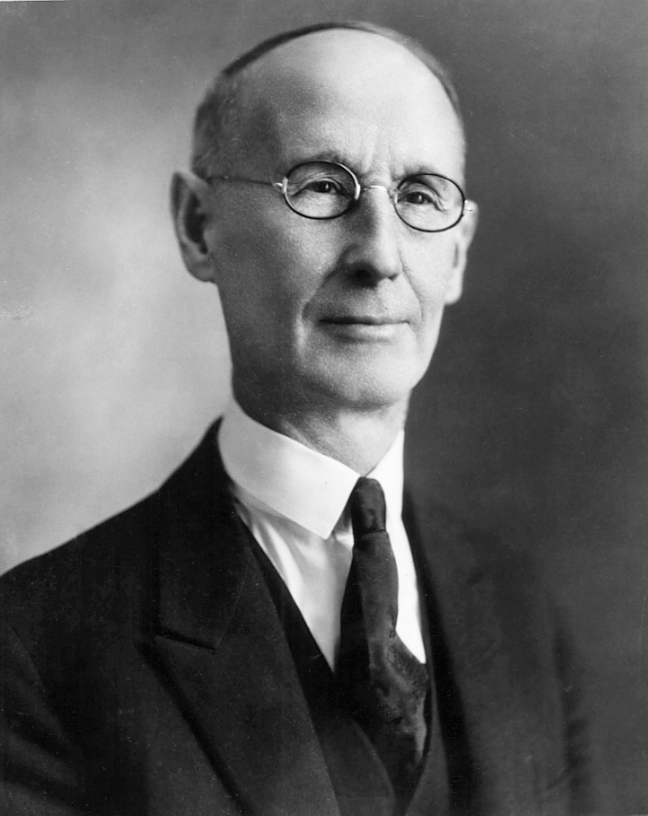

J. Golden Kimball served as a mission president and endorsed traveling without purse or scrip because it allowed for the exercise of greater faith. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

J. Golden Kimball served as a mission president and endorsed traveling without purse or scrip because it allowed for the exercise of greater faith. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Although traveling without purse or scrip was an economic necessity for the vast majority of Mormon missionaries, it probably also was perceived as a rite of passage by some. While having many obvious disadvantages, this method of traveling did possess some benefits. Most elders would not have been financially able to fully support themselves as well as their families at home while serving a full-time mission. Even though few elders traveled with absolutely no money, they spent what little they had very frugally—usually only when they had missed several consecutive meals or when hosts occasionally demanded payment. Moreover, this type of traveling appears to have been an effective missionary tool. By requiring missionaries to mingle so closely with families, it is probable that more baptisms resulted from these intimate associations than from elders’ mass meetings. [11] Finally, SSM president J. Golden Kimball believed this method produced powerful faith in the missionaries: “The great majority of men, with few exceptions . . . [cannot] exercise the same faith, when provided with plenty of money, as can the poor, humble, dependent servant of God, who feels that he is no better than his Master.” [12]

In addition to traveling without purse or scrip, nineteenth-century missionary service often entailed leaving families [13]—either wives and children or parents—and confronting a new country, language, or culture, all with no formal training. Southern States missionaries, in particular, needed to possess courage, boldness, tenacity, and a strong commitment to their religion. These qualities enabled elders to enjoy the good times and endure the bad.

Preparing for Missions and Arriving in the Field

A significant proportion of Southern States missionaries kept journals, several of which have been preserved in various Utah archives. Although the journal authors served in different localities at different times, a surprising uniformity exists among the records. Many elders discuss receiving their mission calls, being set apart by the Church’s General Authorities, and traveling to their respective destinations. Several also describe the new landscapes, culture, and foods. Nearly all diaries record similar experiences of sickness, traveling without purse or scrip, allaying prejudice, and encountering persecution. These journal accounts detail the intricacies of missionaries’ lives, revealing the drastic changes in climate and culture between the West and the South. Thus, culture shock, illness, happiness, uncertainty, and anxiety punctuated nineteenth-century missionaries’ lives in the Southern states.

All missionaries from the West were instructed to pass through Salt Lake City to be set apart and ordained by a General Authority and receive parting advice. Elder B. H. Roberts recalled that he was one of forty-two men, each called to various missions, to be set apart. Roberts noted that all but two received promises of a safe return from their mission; he then “wondered if it were significant” that he did not receive such a promise. [14] Another missionary, Elder George H. Carver, noted that in addition to the ordination, they also received a “vast amount of fatherly advise [sic],” but he failed to record the particulars. [15] Another missionary, Elder James Hubbard, outlined some of the instruction he received: he was warned against over confidence; cautioned about deceitful men; counseled to avoid relationships with women; and instructed to seek the Holy Spirit, keep the commandments, and eschew sin. [16]

Once the elders had completed their business in Salt Lake City, they left for their respective missions. Since the transcontinental rail line ran through Ogden, Utah, this city, forty miles north of Salt Lake City, became the departure hub. If family or friends lived nearby, they usually accompanied the missionaries to the depot. Elder George H. Carver noted that “a large concourse of brethren and sisters” came to “the depot to witness our departure.” [17] Missionaries often left in groups, although not all were destined for the same mission. The companies eventually separated as each elder took his different route. The long hours on the train often induced reflection and contemplation of future labors. In some cases, the train trek itself presented opportunities for missionary work. [18]

The majority of missionaries bound for the South, and almost all who returned from the region, traveled through Kansas City. Consequently, a few elders took the opportunity to visit nearby Church history sites and meet important people from the era of Mormon settlement in western Missouri. [19] From Kansas City, trains usually passed through St. Louis and then arrived at the missionary’s assigned region, or, in later years, at mission headquarters in Chattanooga, Tennessee. [20] Before the official mission headquarters was established in Chattanooga in 1882, elders traveled directly to their assigned areas. This arrangement occasionally caused problems for new missionaries. Notices of arriving elders did not always travel quickly, and if they did, the problem of logistics had to be addressed. Senior companions could not always meet new elders at the depots, so these missionaries were often required to travel to a rendezvous point alone over unfamiliar territory.

Examples of Hospitality

The South, whose hospitality has occasionally reached folkloric proportions, generally provided for most of the missionaries’ needs in part due to the notion of honor and its power to command resources. [21] Since Mormon elders tended to travel without purse or scrip, they wandered from house to house, rarely spending more than one night in the same place—unless Church members or relatives hosted them. Because elders’ regular itineraries necessitated constant travel to secure lodging, missionaries typically walked between one and twenty miles a day and occasionally more. Traveling such great distances on foot, or as one elder called it, “Mormon Conveyance,” [22] was physically taxing. And many missionaries did so on empty or nearly empty stomachs. For example, Elder Henry Eddington casually recorded one day that he had “Traveled 10 miles, had no dinner.” [23] Occasionally, some elders were able to snack on fruit or raw vegetables by the roadsides. [24]

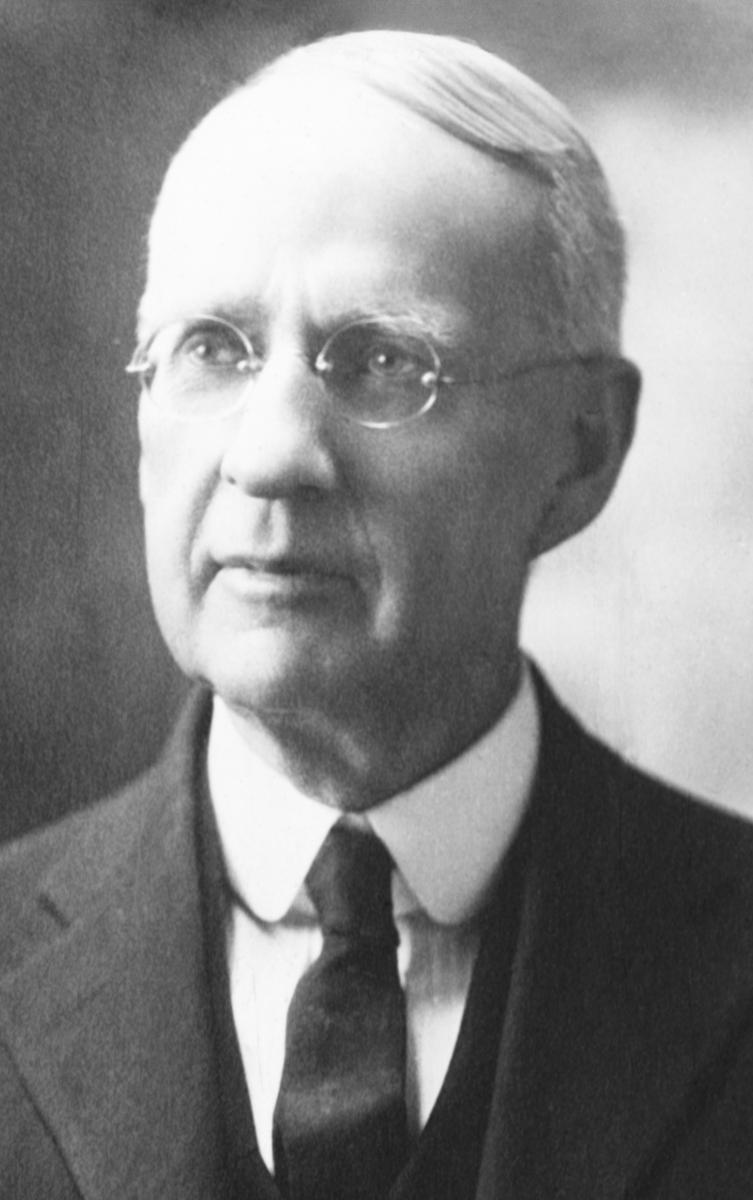

Rudger Clawson recalled feeling a great deal of apprehension over asking for food on his mission. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Rudger Clawson recalled feeling a great deal of apprehension over asking for food on his mission. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Despite such hardships, elders generally managed to receive enough food to sustain their demanding regimen of walking, and they slept indoors more often than outdoors. Southerners, in general, treated the elders well and basically kept them fed. For example, Elder Briant Copley, clerk of the South Alabama Conference, wrote a letter to the Salt Lake City Deseret News extolling Southern hospitality: “It is a well known fact that the people of the South are the most hospitable of any in America, and we Elders . . . are taught a lesson in charity an[0] unselfishness that time can not obliterate.” [25]

Even though most Southerners were hospitable, missionaries could not idly wait to receive their help—they had to request it. Asking for food and lodging, however, required a lot of nerve and not a little desperation. For example, Elder Rudger Clawson described the inhibition he felt the first time he asked for a meal. While traveling to meet his new companion, he became very hungry and came upon an “unpretentious home.” He concluded to “ask for a meal of victuals, something I had never done in all my previous life. I shrank at the idea. I felt embarrassed, I felt humiliated. It seemed to me I would be acting the role of a beggar.” However, hunger helped expedite his rationalization and diminish his fears. Clawson remembered a scripture: “‘The laborer is worthy of his hire.’ [D&C 84:79] And upon further reflection, I readily perceived that the true gospel of Jesus Christ, involving the principle of salvation, which I was authorized to offer the woman, would more than offset the value of the food given a thousand times. Thus reasoning, I felt perfectly justified in boldly asking for something to eat.” The woman invited him in and fed him. At the end of the meal, Clawson thanked his hostess and explained his mission; the woman was not interested, so he continued his journey. [26]

At times missionaries encountered difficulty when seeking “entertainment,” their term for lodging. Elder Oliver Belnap’s experience illustrates this point. One night, he and his companion approached a house, “tired and hungry and foot sore.” The man in the house, a Mr. Argabite, was “not prepared to keep strangers,” but he did not particularly want “to turn any one away at this time of night.” Mrs. Argabite explained how she had washed clothes all day, so there would be no bed, and that she was too tired to fix supper. The missionaries quickly assured her their only necessities would be a blanket and a floor. [27] When the Argabites still hesitated, Belnap appealed to their sympathies: “If we cannot get to stay here we will have to lie out before we can get to another house [and] the people will be in bed. . . . Don’t go to any bother on our account. We can do without supper.” Belnap concluded his journal entry by commenting they had received entertainment “just by a scratch. . . . [And] we thanked God for [it] and not particularly the man for had not the Lord softened his heart we would have laid out that night.” [28]

In some cases when missionaries were denied lodging, they tried to find other types of shelter, such as unlocked schoolhouses or churches, or abandoned barns and houses. [29] Nonetheless, some missionaries occasionally endured the unpleasant experience of having to sleep outdoors. For example, Elder Willard Bean and his companion solicited for lodging one evening. “Home after home turned a deaf ear, some saying that they never entertain strangers.” Nevertheless, the men retained hope that someone would help them, so they continued “until we could see no more lighted houses, then we headed into the woods, held prayer, then assembled enough oak leaves to made [sic] a soft pallet and curled up for the night.” This was particularly arduous since it occurred sometime in January or February, cold months to sleep outdoors even in the South. [30]

Missionaries occasionally performed chores for their hosts, obviously as a type of payment and as a goodwill gesture. Mission president William Spry even encouraged elders to labor with the Saints both spiritually and temporally. [31] Such work typically occurred during the planting and harvest seasons and was performed exclusively at the houses of members or serious investigators. While visiting Joseph Hiatt’s family, long-time investigators of the Church, Elder Frederick Morgan and his companion helped harvest Hiatt’s tobacco crop. [32] Elder Joseph E. Johnson and his companion helped their host, a Brother Spradlin, age ninety-three, build a new corn crib. [33] And Elder John M. Fairbanks helped a local member plant potatoes. [34]

The overwhelming majority of missionaries in the SSM found their hosts generally hospitable. For example, two missionaries assigned to labor in Jones County, North Carolina, explained, “[Southerners] are very kind and hospitable to us Elders: they give us their best beds to sleep on, plenty of good food to eat, and everything else necessary for our comfort and enjoyment.” [35] Another set of missionaries wrote, “We find the people as a rule are very friendly toward us, but they do not seem to understand the necessity of finding out, and complying with the plan of salvation. . . . We are satisfied that there are at least thirty families here [Aiken County, South Carolina] that are always glad to see us and that make us welcome.” [36] After returning home from a mission to the Southern states, Elder J. W. Cook stated, “There was a feeling of indifference on the subject of religion, but the people were kind and hospitable, and many were induced to listen to the Elders’ testimony.” [37]

Many missionaries had difficulty adjusting to the Southern diet. The typical bill of fare at this time consisted of corn bread, bacon, and coffee. [38] A close examination of missionaries’ diaries and letters reveals that the change of diet often caused severe indigestion and heartburn. [39] One missionary wrote, “It will be some time perhaps before we can accustom ourselves to their . . . food. . . . I do not feel as well as I would like to. It is biliousness I think. I expect the pig meat does not agree with me.” [40] Some elders also mentioned their encounters with new and regional or exotic foods. For example, one recorded the first time he ate cornbread, [41] one his first sweet potato, [42] one his first turtle, [43] and another his first opossum. [44]

A Deseret News article accurately noted the disparity in the information recorded by missionaries—“[Southerners’] good qualities are spoken of in general terms, while the exceptions are detailed at length.” [45] Perhaps this helps to explain the multitude of detailed accounts of persecution that missionaries encountered.

Examples of Hostility

Historically, the American South has been characterized by a predisposition for violence. H. C. Brearley identified the South as “that portion of the United States lying below the Smith and Wesson line.” [46] The negative perceptions among white Southerners of Radical Reconstruction and Carpetbag governments led to many unfavorable images of non-Southerners, and these experiences did not endear newly arrived outsiders to native Southerners. As a result, some despised or distrusted foreigners; and it is not surprising that they greeted LDS missionaries, mostly Westerners, with hostility. [47] Moreover, some of the basic doctrines of the LDS Church challenged the dominant Southern religious culture, which was predominantly Protestant Christian. A hierarchy of persecution existed that escalated from written threats, to verbal harassment, to physical assaults, to forced expulsion from the community, and even to attempted and actual murder. Missionaries could never predict which threats would be acted upon.

In the nineteenth century, the LDS Church existed outside the realm of mainstream Christianity in the United States for many reasons. Among these reasons were Mormons’ use of additional scripture to the Bible and the practice of polygamy, neither of which was acceptable to the majority of rural Southerners. A homogeneous culture can maintain solidarity relatively easily, so any who challenge this uniformity, intentionally or unintentionally, may incur the wrath of the majority if perceived as a threat (to honor). As Samuel Hill put it, “Claims of orthodoxy have functioned to maintain group identity and solidarity.” [48] Thus the Latter-day Saint faith challenged the dominant religious culture in the region.

For example, many Southerners were repulsed by Mormon doctrine. [49] They perceived the Mormons’ use of scripture other than the Bible to be heretical to the foundation of pure Christianity. In one case, a well-meaning Southerner advised a missionary to omit his testimony of Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon from his sermon: “He intimated that I did not know how much danger I was in and said there were men who were willing to ‘gore’ me through for my testimony.” However, Elder Nathan Tanner recorded in his journal that his testimony of these things was the reason he was preaching—otherwise, he would go home. He then explained that he feared God’s judgments more than those of a mob. [50]

Another missionary, an Elder N. L. Nelson, had an encounter with a Methodist minister by the last name of Thompson who published an article in the Mountain Echo (Keyser, Virigina) newspaper that was “full of the old slanders so often exploded where our people have had a chance to reply.” Elder Nelson wrote an article in reply. The newspaper would not publish it, and the minister said, “I consider [Mormonism] the most stupendous fraud ever gotten up.” When Elder Nelson asked if he had ever read the scripture, the man replied, “No, but I have sketched it; I have been used to reviewing books, and I can tell the nature of some books from three sentences. It is no use to talk to me of ‘Mormonism.’” The minister then concluded by saying he considered it his “duty to myself, my fellowman and my God to do everything I can against you.” Elder Nelson surmised the minister “may have taken this course to redeem his character, and with some he will undoubtedly be considered a great champion of Christianity.” [51]

Rumors about polygamy and Mormons had circulated throughout the nation beginning in the 1850s, and the rumors only escalated during the rest of the century. Concerted “reform” campaigns also capitalized on the rumors and attempted to abolish polygamy. Furthermore, most newspaper coverage was far from complimentary. [52] Many Southerners perceived polygamous men to be sexual predators, and lurid rumors abounded that Mormon missionaries were recruiting more women into the practice, destroying marriages, stealing wives, and smuggling them to Utah. [53] John Morgan was probably referring to such tales when he stated that many “strange and peculiar ideas prevail in regard to the objects and intents” of Latter-day Saints. [54] Such rumors, combined with orchestrated negative information coming from the anti-Mormon press and churches, promoted prejudice and encouraged opposition. Consequently, many Southern churches prohibited missionaries from preaching in their buildings, [55] and some ministers persuaded their congregations to simply avoid the elders’ meetings.

These rumors helped some Southerners justify violence toward Mormons. [56] Somewhat ironically, Southerners’ antipolygamy sentiment had an added benefit of bringing the region into the good graces of Northerners following the Civil War, thus producing a cultural reconciliation through uniting against a common enemy. [57] Honor played into this hostility because some Southerners felt they were protecting their community against a legitimate threat to the acceptable social order. Although most citizens considered polygamy repugnant before 1879, once the US Supreme Court ruled against plural marriage in Reynolds v. the United States, elders constantly came under attack for their belief in the principle. [58] In effect, this case elevated polygamy to a higher-profile issue.

Slavery and polygamy had been dubbed the “twin relics of barbarism.” In fact, Southerners’ defense of slavery had been based on a literal reading of the Bible, and Southerners’ continued racism rested partly on scriptural arguments. One could assume that some Southerners wondered why they had had to relinquish their slaves while the Mormons had retained their wives, at least until 1890, when Church President Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto, calling for an end to new polygamous marriages. Missionary diaries frequently commented on the region’s double standard, since many Southern men had black mistresses and illegitimate children but still seemed to be repulsed by plural marriage. [59]

For many missionaries, this was their first experience outside the Intermountain West and the Mormon cultural region. To a certain extent, they had been sheltered from having to justify and preach their beliefs to others. Thus individual missionaries had little direct experience with prejudice and persecution until they arrived in the South.

One missionary quoted a contemporary newspaper article: “There was no more law against killing Mormons than there was rattle snakes and if they come on his place he would take his gun and blow their brains out.” [60] Such statements were not always idle talk: between 1879 and 1898, five missionaries were killed in the SSM, [61] and hundreds of others were beaten or physically abused by mobs. [62] In the cases of Joseph Standing in 1879 and William Gibbs and John Berry in 1884, mobs exacted the ultimate price—life. [63]

Other Mormon missionaries had less violent experiences with different outcomes. For example, in 1881, Elder W. Scott and his companion were roused from bed by a noisy, vicious mob late one Saturday night. The mob included half a dozen men, who threw rocks at the house, fired their pistols, and yelled “like demons.” After a few minutes, the disorderly crowd retreated from the host’s property. However, they continued yelling and shooting their guns throughout the night. Elder Scott, explaining the events to fellow missionaries, wrote that he was able to sleep in spite of the perilous situation. Assessing the situation for his audience, he poignantly penned, “Ala. is raging, Hell is boiling. The believers are afraid, saints tremble.” [64]

In 1883, Elder John Alexander was confronted by a mob on a Georgia road and was asked if he was a Mormon. When he replied affirmatively, the leader proclaimed, “Well, you’re going to die right here.” Elder Alexander, fearing for his life, asked that he be allowed to pray. The leader agreed with the stipulation that he “be damn quick about it.” Then the mob lowered their pistols and shot. Alexander closed his eyes and fell to the ground. Miraculously, none of the three bullets hit his body. Not waiting for an invitation to leave, he darted away to safety. Minutes later, Alexander realized that two of the three balls had come dreadfully close: one had passed through his hat and another had gone through his unbuttoned coat. [65]

In another instance in 1887, Elder Parley P. Bingham and his companion were reading quietly in their host’s house in Union County, North Carolina, one evening when a sixty-man mob surrounded the property. The host walked outside and counseled with the disorderly crowd. When they demanded to talk to the missionaries, the host forbade the elders to go out or the mob to enter. This enraged the rabble, who then notified the elders to leave the county by sunrise, or “they would deal roughly with us. They then left the house, whooping and yelling and discharging their guns.” The missionaries temporarily ignored this threat and preached their scheduled meeting the following day. Threats continued to circulate, and by the end of the week, both men “deemed it best [to leave the area and] to go back among our friends.” [66]

In 1893, Elder Hyrum Carter and his companion also received violent treatment. One hot summer day he reported that a horde seized him and his companion. They marched “all day through sand ankle deep,” traveling fifteen miles. When night came, all slept out in the woods. The following morning they marched ten additional miles. The missionaries failed to record the particulars of the conversation during their forced march. It is not unreasonable to speculate, though, that the conversation probably entailed many personal assaults relating to the missionaries’ beliefs. When the crowd reached “a very lonely spot,” each elder received twenty-two lashes. Mob members then destroyed all their Church literature. Afterward, the rabble escorted them to the depot and deposited them on a train for Utah. Elder Carter and his companion traveled only as far as Columbia, South Carolina, where they disembarked and then walked fifteen miles to a friend’s house. [67]

Conclusion

Nineteenth-century missionary life could be physically, emotionally, and spiritually taxing. Elder Charles Flake explained his situation, which was representative of many of his colaborers’ circumstances: “Here I am without friends and with but very little money trying to propigat [sic] a doctrine that the very name of which brings reproach to my carictor [sic] among the so called Christian world.” [68] Enduring such circumstances required a person to have unyielding belief in his religion, exceptional courage, and a strong sense of commitment and purpose.

Despite the general bias against Mormons, many Southerners did believe the missionaries’ message. In the latter quarter of the nineteenth century, more than 1,760 elders baptized 3,839 people. [69] However, some postponed baptism because of pressure from family, friends, and neighbors, or because of fear of reprisals from the community. [70]

Many missionaries described their time in the South as being invaluable. Elder James Hubbard explained: “[This mission] surely has been a great experience, giving me knowledge and experience which I consider invaluable also [a] testimony of the truth of the work. . . . I have made quite a number of friends and have most always been treated very kindly by the good people of the South Many of whom I greatly love.” [71] This summary of one elder’s mission is representative of many more. In the same passage, Elder Hubbard further disclosed, “I have experienced some of the most supremely happy moments of my life, while at times I have been greatly tried.” [72] Extant diaries, by and large, retain a sense of optimism amid trials and challenging circumstances.

SSM elders encountered Southern honor through both hospitality and hostility. Hospitality facilitated missionary work on some levels while hostility obstructed it. When hostility came in the form of persecution, it often involved bodily harm, but to some missionaries it was an external validation that they were doing God’s work. [73] Had this degree of hospitality not existed in the South, it is hard to believe that Church leaders would have continued to send elders to the region, because of the extent of violence encountered by missionaries there. [74] Stories of persecution and anti-Mormonism grab readers’ attention and turn readers into voyeurs. But the stories of hospitality offer balance and perspective to the missionaries’ experiences during their Southern sojourns. And the concept of honor explains how these two opposite extremes were able to coexist.

Notes

[1] Leonard J. Arrington, “Mormon Beginnings in the American South,” Task Papers in LDS History, no. 9 (Salt Lake City: Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1976), 14–17. Arrington noted that Southerners never accounted for more than 2 percent of the total LDS population.

[2] This group of converts from Monroe County, Mississippi, wintered in present-day southern Colorado in 1846. There they were joined by more than 150 ill members of the Mormon Battalion. Many of the Mississippi Saints were among the first Mormon settlers who helped plant late summer crops in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. See Leonard J. Arrington, “Mississippi Mormons,” Ensign, June 1977, 46–51.

[3] David Buice, “‘All Alone and None to Cheer Me’: The Southern States Mission Diaries of J. Golden Kimball,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 24, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 38.

[4] Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (New York: Oxford, 1982), 327–39, 362–401.

[5] Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor, 61. Although Wyatt-Brown’s book deals with antebellum Southern culture, many of these same characteristics are prevalent in the South well into the twenty-first century.

[6] This concept appears in some of the Southern history literature. In some senses, commanding resources may mean extending hospitality, offering food, and giving shelter. In this case, however, it probably also included marshaling defenses (people, munitions, etc.) to protect the missionaries.

[7] Lawrence M. Friedman, Crime and Punishment in American History (New York: BasicBooks, 1993), 180; see also Edward J. Blum and W. Scott Poole, eds., New Essays on Religion and Reconstruction (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005).

[8] Thomas D. Clark, “The Country Newspaper: A Factor in Southern Opinion, 1865–1930,” Journal of Southern History 14, no. 1 (February 1948): 23. Edward L. Ayers believed “honor was just another word for lack of self-control.” Edward L. Ayers, Vengeance and Justice: Crime and Punishment in the Nineteenth-Century American South (New York: Oxford, 1984), 25.

[9] “History of the Southern States Mission,” Latter Day Saints Southern Star, December 3, 1898, 1. See also “Fourth Day, Saturday, 10 a.m., Oct. 9,” Deseret News, October 9, 1875; and “Departure of Missionaries,” Deseret News, November 1, 1875.

[10] J. Golden Kimball, “Our Missions and Missionary Work,” Contributor, July 1894, 550.

[11] After arriving at these ideas independently, I learned that historian Chad Orton had noted similar benefits. In a family history project, Orton listed three advantages: “First, it allowed Church leaders to call on missions men who might not otherwise be able to serve because of financial constraints. Second, in an era of few members and even fewer branches outside Utah, it allowed for greater contact between the local members and the missionaries, often the members’ only link to the Church. . . . Third, it allowed missionaries to discuss the gospel with individuals who might not otherwise have taken the opportunity to listen to the elders.” Chad Orton, “Southern States Missionary,” copy in author’s possession.

[12] Kimball, “Our Missions and Missionary Work,” 550. This statement was probably made in an attempt to persuade elders and their families that going without purse or scrip was the best method of travel. In practice, however, few missionaries traveled entirely without any financial resources in the 1890s, partly because of vagrancy laws.

[13] Many nineteenth-century missionaries were married to at least one wife. However, there were some younger, single elders as well. The mean age of Southern States elders at ordination was 29.7 years old; the median age was 27.5 years old. Heather M. Seferovich, chap. 3 in “History of the LDS Southern States Mission, 1875–1898” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1996).

[14] It was Roberts’s opinion that this promise of safety was a relatively common clause in ordinations. B. H. Roberts, “Life Story of Brigham H. Roberts,” B. H. Roberts Collection, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[15] George H. Carver, Missionary Journal, June 1879, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah (hereafter cited as HBLL).

[16] James Hubbard, Diary, April 12, 1895, HBLL.

[17] Carver, Missionary Journal, June 1879.

[18] For example, while Elder B. H. Roberts was traveling, he explained that passengers from another car discovered the missionaries’ presence on the train and requested that one come talk to them. Roberts, Papers, box 1, book 1, 70.

[19] For example, John Morgan, Matthias Cowley, and Nathan Tanner all visited David Whitmer, one of the three witnesses to the Book of Mormon. Morgan and Cowley also called on Mormon advocate General Alexander W. Doniphan. John Morgan visited David Whitmer twice, first on April 13, 1882, with Matthias Cowley and then again on March 1, 1883. See John Morgan to John Taylor, April 20, 1882, John Hamilton Morgan Papers, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Nathan Tanner met Whitmer on May 11, 1886. See Tanner, Diaries, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[20] From 1867 to 1875, the mission had no official headquarters; the mission president’s field of labor was considered the administrative office. By 1877, however, a small room that doubled as an office was rented in Nashville, Tennessee; mission headquarters remained through until October 1882, when President John Morgan moved to Chattanooga. Although no official reason exists for the move, Morgan’s diary intimated that cheaper railroad fares played a role in the decision. See John Hamilton Morgan Papers, October 4–9, 1882.

[21] See, generally, Joe Gray Taylor, Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982); and Helen Hardie Grant, Peter Cartwright: Pioneer (New York: Abingdon Press, 1931). Cartwright, an itinerant Methodist preacher who traveled around the South in the late nineteenth century, was also a recipient of the hospitality extended to missionaries generally.

[22] Elder Henry Eddington used this term throughout his diary. See Henry Eddington, Mission Diaries, HBLL.

[23] Eddington, Mission Diaries, May 12, 1886.

[24] See Frederick Morgan, Diaries, May 31, 1890; June 2, 1890; June 11, 1890, HBLL; and Willis E. Robison, Mission Journal, June 29, 1883, HBLL.

[25] Briant Copley, Southern States Mission, Manuscript History, November 5, 1893, Church History Library.

[26] Rudger G. Clawson, Papers, box 1, folder 1, 34, Marriott Library.

[27] This would have been much more comfortable than waking up saturated in the South’s thick morning dew.

[28] Oliver Belnap, Diaries, July 8, 1889, Church History Library.

[29] For example, because Elder Willis E. Robison and his companion had been refused lodging, they found an unlocked church and slept on the pews. The two men took turns guessing which denomination owned the church. Robison’s companion thought it belonged to the “Campbellites, on account of it being so neatly finished. But . . . after lying on the benches all night I told him that I thought that it was Hard Sides [Baptist].” Robison, Mission Journal, June 15, 1884.

[30] Willard Washington Bean, Autobiography, 32, Church History Library.

[31] Belnap, Diaries, September 13, 1889.

[32] Frederick Morgan, Diaries, September 16, 1891. Six days later, Elder Morgan and his companion helped a local member: “Bro P having decided to cut his tobacco crop we all volunteered to assist him” (September 22, 1890). The Church’s Word of Wisdom was not strictly enforced until 1930, when obedience to it was required for a temple recommend; see Joseph Lynn Lyon, “Word of Wisdom,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillian, 1992), 4:1584–85.

[33] Joseph E. Johnson, Mission Journal, November 11, 1886, HBLL.

[34] John M. Fairbanks, Mission Journals, May 7, 1883, HBLL.

[35] John C. Halt and Jas. R. Hansen, “North Carolina’s Hospitality,” Deseret News, February 26, 1898.

[36] Job H. Whitney and D. C. Woodward, “Southern Hospitality,” Deseret News, March 7, 1896.

[37] “From the South,” Deseret News, April 19, 1890.

[38] Eddington, Mission Diaries, 141. See, generally, Taylor, Eating, Drinking, and Visiting.

[39] See John Henry Gibbs to Louisa H. Gibbs, Mission Journals, March 16, 1883; John Henry Gibbs to Louisa H. Gibbs, n.d. (between April 28, 1883, and May 17, 1883), HBLL. It took Gibbs two months to adjust to this diet.

[40] Frederick Morgan, Diaries, March 20, 1890, HBLL. As if the food weren’t bad enough, the sanitation level varied from house to house. Once, Elder Morgan wrote that he had trouble stomaching his food since the hosts were “very untidy, [and] the house fairly stinks.” Morgan, Diaries, April 25, 1890. Elder John Henry Gibbs recorded a similar experience with sanitation and food. See John Henry Gibbs to Louisa Gibbs, January 11, 1884, Gibbs, Papers, HBLL).

[41] Eddington, Mission Diaries, May 2, 1886. Cornbread had been a staple during the Nauvoo period of Church history, but these missionaries were members of the second and third generations, long removed from Nauvoo. Obviously, cornbread did not continue to be a common food for many Utah families.

[42] Joseph E. Johnson, “Personal Journal of the Travels and Experiences of Joseph E. Johnson of Huntington, Utah, to the Southern States,” typescript, 3, HBLL.

[43] Frederick Morgan, Diaries, June 21, 1890.

[44] Robison, Mission Journal, October 11, 1883.

[45] “Proselyting in the South,” Deseret News, March 3, 1886.

[46] H. C. Brearley, “The Pattern of Violence,” in Culture in the South, ed. W. T. Couch (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1935), 678.

[47] Of the 1,693 elders who served in the South from 1867 to 1898, 1,188 were born in Utah and 69 in other western states. See Seferovich, chap. 3 in “History of the Southern States Mission.”

[48] Samuel S. Hill, ed., Religion, vol. 1, in The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. Charles Reagan Wilson, James G. Thomas Jr., and Ann J. Abadie (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 154.

[49] This is a contradiction to Patrick Mason’s research in Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormonism in the Postbellum South (New York: Oxford, 2011), which primarily emphasizes the impact of polygamy on Southerners’ perceptions of Mormons.

[50] Nathan Tanner, Diaries, August 19, 1884, Church History Library.

[51] William P. Camp, “Missionary Experience in the South,” Deseret News, August 5, 1885.

[52] See Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Graphic Image, 1834–1914 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 33–71; Mason, chaps. 4–7 in Mormon Menace.

[53] See James Thompson Lisonbee, Correspondence, February 21, 1877, Church History Library; Fairbanks, Mission Journals, May 23 and 27, 1883; SSM Historical Records and Minutes, series 11, August 1884, Church History Library; Edward Crowther, Diaries, January 26, 1886, Church History Library; and Z. S. Taylor, Journal, July 21, 1886, HBLL. Elders were not allowed to take plural wives while serving missions.

[54] John Morgan Papers, also printed in “Discourse Delivered by Elder John Morgan,” Deseret News, September 16, 1893.

[55] See Walter Brown Posey, Religious Strife on the Southern Frontier (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1965), 69.

[56] See Patrick Q. Mason, “Opposition to Polygamy in the Postbellum South,” Journal of Southern History 76, no. 3 (August 2010): 543; and Mason, chaps. 3–4 in Mormon Menace.

[57] See Mason, chaps. 4–5 in Mormon Menace.

[58] See James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 363–65, 399–407, 412–22; and Gustive O. Larson, chaps. 2–3 in The “Americanization” of Utah for Statehood (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1971).

[59] For the Southern reaction, see David Buice, “A Stench in the Nostrils of Honest Men: Southern Democrats and the Edmunds Act of 1882,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 21, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 100–113. Paul Harvey dubbed this “theological racism.” See Harvey, Freedom’s Coming: Religious Culture and the Shaping of the South from the Civil War through the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

[60] Redrick Reddin Allred, Diary, July 8, 1886, Church History Library.

[61] See William W. Hatch, There Is No Law: A History of Mormon Civil Relations in the Southern States (New York: Vantage, 1968). Hatch examines each of the murders in his book. See also Mason, chaps 2–3 in Mormon Menace.

[62] Mason has identified more than three hundred documented cases of violence. See Mason, chap. 7 in Mormon Menace. Moreover, mobs’ abuse was not solely confined to the missionaries. Sometimes mobs vented their anger on those who housed and fed elders. Mobs even abused some of the animals the missionaries used. For example, Laura Church, a Saint in Tennessee, occasionally loaned her horse, Traveler, to sick elders or conference presidents. Several missionaries had borrowed him “and he has ‘suffered for the gospels sake’” because a mob had cropped both his ears and his tail. Brigham H. Roberts, A Scrap Book, ed. Lynn Pulsipher, 2 vols. (Provo, UT: Pulsipher, 1989), 1:128–292.

[63] For more information on these murders, see Hatch, chaps. 1–3 in There Is No Law.

[64] W. Scott to Brothers Daniels, Taylor, and Packer, September 6, 1881, in John Morgan Papers, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

[65] John Alexander, “Our Injured Missionary,” Juvenile Instructor, 1883, 207.

[66] Parley P. Bingham, “The Missionary Field: Lively Experience in the South—Futile Threats,” clipped from the Ogden Herald, Journal History of the Church, March 1, 1887, 6–7, Church History Library.

[67] Hyrum Carter, Diary, July 13–14, 1893, Church History Library.

[68] Charles Flake, Diary, May 14, 1884, HBLL.

[69] See Seferovich, chap. 3 in “History of the Southern States Mission,” for more information on these statistics.

[70] For example, Elder William Winn explained how a woman wished to be baptized, but her husband was “very bitterly opposed to it and he told her that when she went out of his door to get baptized she should never enter it again.” When her sister and friends “turned against her,” she chose not to be baptized. See William H. Winn to Dear Wife and Children, in William H. Winn Letters, January 23, 1879, HBLL. Under President John Morgan, missionaries were required to obtain consent from husbands before baptizing these men’s wives. See Morgan, Papers, May 7, 1885.

[71] James Hubbard, Mission Diary, March 23, 1897, HBLL.

[72] Hubbard, Mission Diary, March 23, 1897.

[73] Elder Charles Flake illustrated such feelings perfectly in his April 7, 1884, diary entry: “Last night we was talking of how every thing [sic] was and I made the remark that there was so little opposition I feared we weren’t doing our duty, but my fears were soon dispelled for about 9 oclock some one hollowed ‘Hello’ Wm & I walked out. Brother Call had gone to bed, two men stood at the fence and refused to answer when we spoke. As we approached them we could see that they were disguised. . . . On our drawing near we could see that one had a shot gun and they boath [sic] had something tied around their heads. However we recognized the speaker as Buck Howell (Mrs. Leggitt’s Brother) but could not tell for sure who the other was.” Flake, Diary, HBLL. See also Mason, chap. 7 in Mormon Menace.

[74] For example, after the 1884 Cane Creek Massacre in Tennessee, the First Presidency debated whether to close the mission. Minutes from these meetings exist; however, access to the documents is restricted.