Jay H. Buckley, "'Good News' at the Cape of Good Hope: Early LDS Missionary Activities in South Africa," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 471–502.

Jay H. Buckley was an associate professor of history at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

Portuguese explorers Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama arrived in South Africa during the last decades of the fifteenth century while seeking an ocean route to India. These European mariners recorded the first descriptions of the South African coast by Christian believers. Several decades later, Jan Van Riebeeck of the Dutch East Indian Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) established the Cape Colony and founded Cape Town in Table Bay in 1652 and instigated the dominant influence of the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk) in the region. After British annexation of the Cape Colony in 1806, the Church of England and other Christian denominations gained a foothold in the area. [1]

Since its founding on April 6, 1830, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has emphasized missionary work. Fewer than six months after the organization of the Church, the Latter-day Saint prophet Joseph Smith Jr. revealed that it was the will of the Lord to preach the restored gospel of Jesus Christ to every nation and to send missionaries to gather his elect from the four corners of the world. South Africa represented one of those remote corners of the globe. During the 1850s and 1860s, the LDS Church initiated missionary activity in the shadows of Table Mountain and other parts of the British-controlled Cape Colony. An examination of the journals of Jesse Haven, William Walker, and other LDS missionaries, as well as the diaries kept by early LDS converts such as Eli Wiggill, reveal the limitations and successes of the Church’s initial proselyting endeavors in South Africa, the challenges the missionaries and converts faced in establishing the Church, and the outcomes of their labors. These accounts chronicle the missionary efforts that established the first LDS presence on the African continent, the labors of early converts who assisted in building and strengthening the fledgling church in Africa, and the efforts of those who strengthened Zion by immigrating to Utah Territory in America.

Several major developments between 1820 and 1850 helped prepare the way for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to initiate its missionary activity in South Africa. The first development occurred in the spring of 1820, at the same time that Joseph Smith experienced the First Vision of the Father and the Son in upstate New York. Across the Atlantic, the British government and the Cape Colony authorities initiated, sponsored, and funded the immigration and settlement of five thousand English settlers to the Algoa Bay area of the Eastern Cape. This Albany Colony was intended to serve as a buffer between the Xhosas (an African confederacy of Bantu-speaking tribes living in the Ciskei/

Thomas Baines, The British Settlers of 1820 Landing in Algoa Bay (1853). These settlers provided a boost to the English-speaking population, facilitated the extension of British administration and control over the area, and eased unemployment in Britain. Courtesy of the Albany Museum, Grahamstown, South Africa.

Thomas Baines, The British Settlers of 1820 Landing in Algoa Bay (1853). These settlers provided a boost to the English-speaking population, facilitated the extension of British administration and control over the area, and eased unemployment in Britain. Courtesy of the Albany Museum, Grahamstown, South Africa.

Second, Anglican and Protestant missionary societies laid the foundation for other Christian denominations to proselytize. The Moravian Church, the Church Missionary Society, the Baptist Missionary Society, the British and Foreign Bible Society, the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society, and the London Missionary Society all gained influence and established missions in South Africa during the first half of the nineteenth century. Although these missionary societies competed with one another over resources and African converts, they also crusaded to spread the knowledge of Christ to all nations, advocated for African causes and civil rights, constructed mission stations, and supported the 1834 abolition of slavery. [3]

Third, British policies, administration, laws, religion, and settlement spurred numerous groups of Afrikaners to leave the Cape and trek overland into the interior. From the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s, perhaps as many as ten to fifteen thousand Afrikaans- or Dutch-speaking pioneers (Voortrekkers) embarked from the Cape on an overland migration to the north and east, seeking new farms and greater freedom from British interference. The Afrikaners’ Great Trek somewhat paralleled the Mormon pioneer migration to the Great Basin that commenced about the same time the Great Trek ended. After many Afrikaners migrated to the interior, the Anglicization process among the remaining inhabitants in the Cape Colony gained momentum. English, which had become the official government language in 1824, proliferated in the court system, the newspapers, and the schools. In 1843, the British annexed Natal as their second South African coastal colony. [4]

Meanwhile, in Nauvoo, Illinois, on April 19, 1843, the Prophet Joseph Smith instructed Brigham Young and the Twelve Apostles to not let “a single corner of the earth go without a mission.” [5] Following Smith’s martyrdom in June 1844, it was unclear how his desire would be fulfilled. Within the next decade, the bulk of the Church membership moved to Utah Territory. Once there, Young and the Church’s leaders began fulfilling this directive. They convened a special Church conference concerning missionary work in August 1852 in Salt Lake City. As the parishioners gathered on Saturday, August 28, they sat listening with both anticipation and perhaps some anxiety as Church leaders read the names of 108 missionaries called to serve in various places around the globe. Three men—Elders Jesse C. Haven, William Holmes Walker, and Leonard I. Smith—received mission calls to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ in South Africa and to establish the Cape of Good Hope Mission. The Sunday session of the conference featured Orson Pratt’s sermon on plural marriage. This was the first public declaration of this marital practice from Church leaders that missionaries were asked to convey to the world. [6]

It was a difficult time for these three married men to embark on their overseas mission. Not only was Haven leaving his first wife, Martha, but his new bride, Abigail, was pregnant with their first son. Walker was leaving his two wives and their young families. Smith had only been married a few months and his wife Eveline was pregnant with their first daughter. Nevertheless, these three married missionary men departed on their South African missions by traveling east along the Mormon Trail, leaving Salt Lake City on September 15 on their way to New York, where they arrived a few months later. On December 17, they purchased passage on the ship Columbia from New York to Liverpool for a ten-dollar fare. After sailing for eighteen days, the elders reached Liverpool, England, on January 3, 1853, and spent five weeks in the British Isles, where they met the British Isles mission president, Samuel W. Richards. Elder Haven recorded, “The Saints in London were very kind in assisting me, and asked, to what few things I still needed, to make my journey comfortable to the eight or nine thousand miles I yet had to sail across the mighty deep to get to my field of labor. And I will say that the Saints in every part of England I visited were extremely kind, frequently compelling me against my will, to receive from them a sixpence or a shilling as a token of their desire and willingness to help me perform the task that lay before me.” [7]

On February 11, 1853, the trio set sail for Cape Town aboard the Domitia. As they neared Cape Town, Elder Walker described a severe storm on April 15 that raged with immense waves threatening to destroy their ship. He recorded, “We prayed to the Lord and rebuked the Winds and waves in his name and they from that time began to Abate and the weather become favorable as also the Winds.” The ship safely docked in Cape Town’s harbor on April 18. [8]

Preaching amid Persecution

The landing of the three elders ushered in a dozen years of LDS missionary activity in South Africa. Journals, published tracts, newspaper articles recounting their activities, and convert diaries and correspondence help reconstruct the early LDS proselyting ventures during the 1850s and 1860s. They convey the persecution the missionaries and those who assisted them faced from other religious leaders and the members of the press, highlight the conversion stories of the faithful, detail the establishment and growth of branches of the Church, and chronicle the subsequent emigration of some of those early converts from South Africa to America.

Penniless, friendless, and thousands of miles from home, the three missionaries set about to teach the gospel in Cape Town, but they faced immediate persecution. Elder Walker’s April 18, 1853, journal entry captures the humble beginnings of the mission: “We thanked the Lord for all the blessings and also so favorable circastances while crossing the sea as a good cabin Pashage for which realized was a blessing from God for we left our homes without Purs or scrip and have no other dependance only in God we as now are landed in a strang Land among strangers with out home and with out friends and with out money.” [9]

Despite the overwhelming odds, they prayed for the Lord’s help to accomplish their task and went to work. On April 23, the first recorded Latter-day Saint service held on the African continent took place in the home of a Mr. Naughton, but not many attended. Two days later, the elders booked the town hall for six consecutive nights and advertised their meetings in the local newspapers. Their first meeting on April 25 drew quite a crowd, but opposition and persecution plagued the elders from the beginning. After Elder Haven taught the first principles of the gospel, Elder Smith bore testimony of the Prophet Joseph Smith. This caused the crowd to form a mob, which broke up the meeting. The only positive outcome was that a gentleman offered them money for their lodging and walked them there to ensure they were unmolested. [10]

The elders found themselves locked out of the town hall the following day, so they delivered a sermon at the Bethel (Sailor’s) Chapel. Shortly after Elder Walker began talking about the Book of Mormon, a mob gathered and started shouting to drown out the missionaries. The elders acknowledged, “We did not continue the meeting as long as we intended.” As the missionaries exited the building, the mob hurled stones and rubbish at them but the elders wrote, “We past through their midst unharmed.” The next night was not any better. They tried to have a meeting “but the people made so much disturbance, we were obliged to dismiss before we had spoken much.” A few days later, a mob armed with sticks and stones formed near the Bethel Chapel, but the missionaries did not appear. Then the mob came to the house where the missionaries lodged and tried to get them to come out, but the elders stayed inside. For the next few weeks, other meetings planned for public halls or private homes were broken up by intolerant mobs that heckled the missionaries and pelted them with rotten eggs and stale vegetables. [11]

The hostility and violence the Mormon missionaries encountered emanated from clergy from the Dutch Reformed and Anglican churches, the two faiths most influential among the Dutch and English inhabitants of the Cape. Elder Walker recounted, “The Clergemen and Ministers are going about from House to House teling the people not to harbour us in their Houses nor feed us and also teach this in publick they are determin to starve us out.” Methodists, Presbyterians, and other faiths also joined together in shunning and preaching against the Mormons. Articles published in the local newspapers supported the preachers’ prejudices by labeling the Mormons “a dangerous sect,” which caused Elder Walker to lament that “all the combined Powers of Earth and Hell is against us.” Hence, the elders left Cape Town and traveled several miles inland to Mowbray, Newlands, Rondebosch, Wynberg, and other communities within the peninsula. [12]

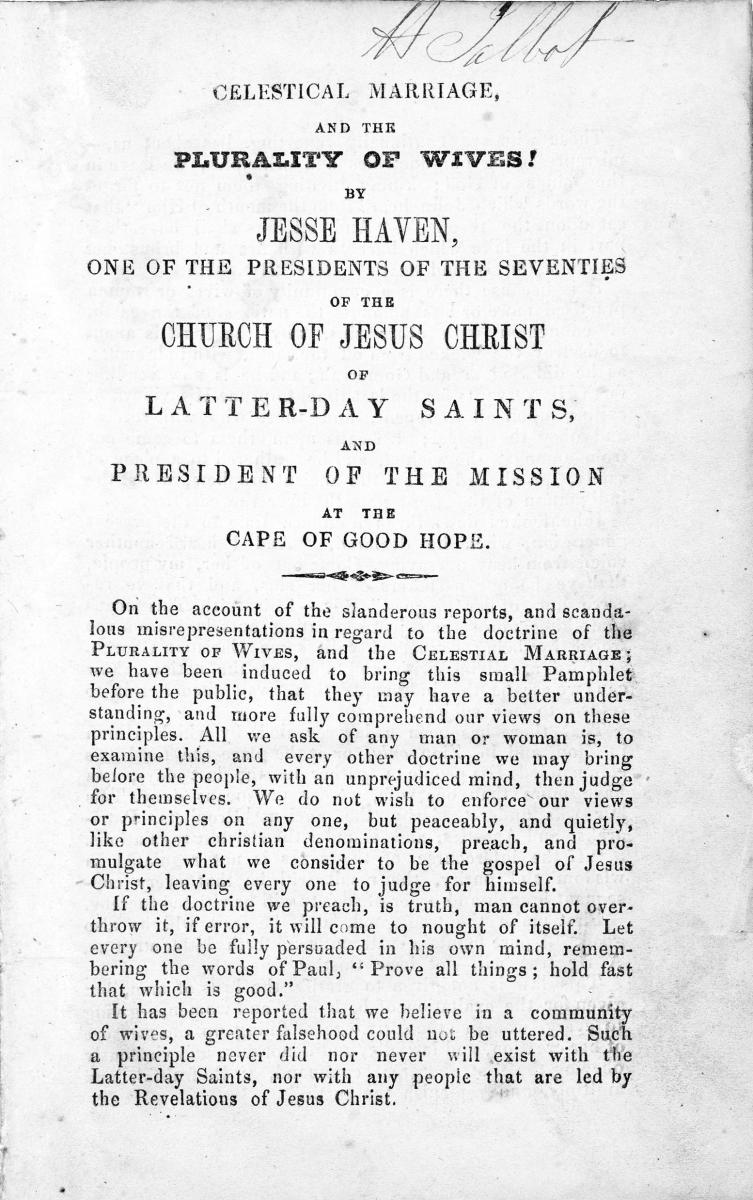

Much of this opposition against the Latter-day Saints resulted from the Church’s public declaration of plural marriage. Ministers and newspaper publishers spread numerous rumors and falsehoods attacking polygamy. A common practice among African nations in South Africa, polygamy was viewed as barbaric by many Christian denominations, especially when practiced by Caucasian Christians. [13] Fortunately, Jesse Haven was a prodigious writer and matched the attacks from the ministers and printers with his own publications, particularly when he could find publishers who would cooperate. During his mission, Haven prepared and printed at least eleven documents defending the Church. A few of these titles included Some of the Principal Doctrines or Beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints; Voice of Joseph; Celestial Marriage, and the Plurality of Wives!; and A Warning to All. [14]

Celestial Marriage, and the Plurality of Wives!, by Jesse Haven, written in 1853 as a response to the rumors and falsehoods attacking polygamy. Note that the printer misspelled the word Celestial.

Celestial Marriage, and the Plurality of Wives!, by Jesse Haven, written in 1853 as a response to the rumors and falsehoods attacking polygamy. Note that the printer misspelled the word Celestial.

Establishing and Expanding the Cape of Good Hope Mission

On May 23, 1853, the three missionaries established the Cape of Good Hope Mission. The trio, who had been subsisting on bread and water for several weeks, climbed the Lion’s Head—the second-most prominent Cape Town landmark next to Table Mountain—“for the purpose of organizing the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Cape of Good Hope.” After singing a hymn and saying a prayer, the trio sustained Haven as the president of the mission and approved Elders Walker and Smith as his two counselors. “Elder Haven then prophesied, that the Church now organized in the Cape of Good Hope, will roll forth in this Colony, and continue to increase, till many of the honest in heart will be made to rejoice in the everlasting Gospel. . . . After we came down off the mountain and came back into town, a man made application to Elder Smith to be baptized, and appointed Thursday the 26 inst. to attend to the ordinance.” Three days later, Smith baptized the first two LDS converts in Africa, Joseph Patterson and John Dodd. The Mowbray (Cape Town) congregation holds the distinction of being the first branch of the Church in Africa, formed on August 16, 1853. The Newlands Branch, created the following month on September 7, was composed of the “meek and the poor.” [15]

Mobs—sometimes numbering two to three hundred people—continued to harass and break up any public meetings the missionaries advertised. The peoples’ prejudices against the Mormons remained very strong. Preachers persecuted those who fed or housed the missionaries, tried to prevent baptisms, and encouraged those who were baptized to abandon their new faith and return to the church of their birth. Haven remarked that the “priests are busy in their exertions against us. Many of them have lectured against us, but they are very careful not to come where we are. They look upon us as a set of poor ignoramuses, and would consider it a great detriment to their dignity to be seen speaking with us, much more to converse upon the plan of salvation.” The preachers instructed their parishioners to lock up their valuables, to not let Mormons into their homes, and to starve them and drive them from the country. [16]

Nevertheless, some accepted the gospel message. Within six months, the elders had baptized forty-five persons, organized two branches, held one conference, and blessed a number of children. New converts sometimes presented the missionaries with a different type of challenge. After Amelia Paine was baptized, her former minister, Reverend Lamb, was adamant that she repent of her mistake and forsake Mormonism. President Haven tried to comfort her, wrote a letter to her minister, and gave her a copy of the Doctrine and Covenants. He also began spending a lot of his spare time with her and confessed in his journal that he had “very kind feelings towards her” and enjoyed their leisurely walks together, arm in arm. Despite missing the association of his young wife Abigail (who had given birth to their son Jesse since Haven’s departure), Haven may have entertained the notion of adding another plural wife. He did not act upon it, however, even though he often preached and wrote about the doctrine of celestial marriage and the plurality of wives. [17]

As the missionaries enjoyed some proselyting success, other developments thwarted their efforts. Persecution from printers and preachers increased. The inability of the missionaries to speak Dutch or Afrikaans impeded their efforts, as did their lack of Church materials, scriptures, and religious tracts in those languages to distribute. Haven wrote Church President Brigham Young that there “are many here who speak the Dutch language, though they have a little knowledge of English; but not enough to read and understand English books. There are also many back in the country, who have no knowledge of the English language. I would like to do a considerable printing in Dutch, but have not yet been able to do much for want of means.” [18]

President Haven’s desires to have the Book of Mormon translated into Dutch did not come to fruition, primarily due to a lack of funds, and his attempts to have pamphlets translated into Dutch faced numerous obstacles. [19] Not one to be deterred, Haven, along with Thomas Weatherhead (a local English-speaking convert and the Newlands branch president), set out for Stellenbosch on January 19, 1855, to preach to the Afrikaans-speaking farmers in the region. The local dominees (ministers of the Dutch Reformed Church) asked their members to boycott Latter-day Saint meetings and occasionally treated the missionaries roughly. Nevertheless, a few Afrikaners expressed some interest in the Church. But Haven lamented to President Richards of the European Mission that he still did not have sufficient funds to have Dutch versions of pamphlets or scriptures and hoped that Dutch-speaking missionaries could soon be sent to preach the gospel in South Africa.

The following month, President Haven and local Anglo member Richard Provis traveled to Paarl, Malmesbury, and D’Urban (Durbanville) to preach to the Afrikaners. The Afrikaans- and Dutch-speaking population made up over half of the white South Africans in the colony, and Haven desired to carry the work to them. Johanna Provis, Richard’s Afrikaner wife, had been giving Haven lessons to help him learn Afrikaans, but he never became sufficiently proficient to preach the gospel in that language. Johanna appears to have been Haven’s only Afrikaner convert during his mission. [20] In addition to the language problems, the Church’s practice at that time did not allow for the ordination of blacks to the priesthood, which limited proselytizing efforts almost exclusively to those of European descent, and primarily to the English-speaking inhabitants. [21]

While President Haven nurtured the Church in the vicinity of Cape Town, Elders Walker and Smith journeyed to the Eastern Cape. Walker traveled overland by horse cart to the villages of Fort Beaufort and Grahamstown, while Elder Smith sailed to Port Elizabeth. The English settlers that had arrived in Algoa Bay in 1820 had augmented the significance of Port Elizabeth’s harbor. They had also developed other communities in the Zuurvelt and the Albany District, especially Grahamstown, the Cape Colony’s second largest city after Cape Town and the cultural center of the Albany District. Smith and Walker drew most of their converts from among the settler families who had arrived from Britain in 1820.

Elder Smith had barely arrived in Port Elizabeth when he was summoned to appear before the magistrate to answer trumped-up charges made against him by a man from Cape Town. His appearance in court on April 4, 1854, resulted in both good feelings and a growing friendship between Elder Smith and the local magistrate, who authorized him to preach wherever he pleased. Nevertheless, despite his initial courteous treatment, it took Smith a month before he was finally able to secure a place to hold a public meeting. Approximately five hundred people showed up and broke up the meeting (and a few windows) by throwing brickbats and potatoes. The magistrate arranged for police to protect Smith and told the people assembled that if they meddled with Smith, he would punish them to the full extent of the law. After the magistrate’s stern warning to the crowd, Smith taught in Port Elizabeth without any further disturbance. [22]

Elder Walker, accompanied by a South African member missionary named John Wesley, was also experiencing some success. Walker organized the third branch in the mission on Thursday, February 23, 1854, at Fort Beaufort, Cape Colony. He also began publishing tracts and notices in the Port Elizabeth Examiner, such as “To the Intelligent Public,” “A Voice of Warning,” and “Replies to Some False Statements.” These publications outlined his logical responses to allegations against the Mormons and served to inform the public about the tenets of the faith. [23] As he taught the gospel in the vicinities of the inland towns of Beaufort, Grahamstown, and Queenstown, Walker was able to teach a man named George Wiggill. Eventually, in February 1855, George introduced him to his brother Eli, who eventually became an important Church leader in the Eastern Cape.

Eli Wiggill, the eldest son of Isaac and Elizabeth Wiggill, had emigrated with his parents from Gloucester, England, as a nine-year-old boy on January 10, 1820. Working with his father until he was twenty-two, Eli married Susannah Bentley in 1831 and spent time in Grahamstown, Bathurst, and Queenstown, working as a wheelwright, wagon maker, and Methodist preacher. He learned Dutch and began to prosper in his trade. In 1846, the War of the Axe commenced with Xhosa reprisals against settler encroachments; the war resulted in the death of several men on both sides and the loss of thousands of cattle and sheep. [24] Wiggill finally settled in Winterberg. In 1850, Eli’s son John was taken captive by native warriors. Eli’s wife, Susannah, met with the Xhosa leaders and arranged for John’s release, which was granted because the African tribesmen knew and respected Eli, who had “often preached to us, he is a good man, he has never done us any harm. We will not kill him, as we want him to make wagons for us.” [25]

Map of Missionary Activity, 1853–65, adapted from Farrell R. Monson, "History of the South African Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1853–70" (master's thesis, Brigham Young University, 1971), 131.

Map of Missionary Activity, 1853–65, adapted from Farrell R. Monson, "History of the South African Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1853–70" (master's thesis, Brigham Young University, 1971), 131.

When the war ended in 1852, the government compensated white settlers who had lost their farms with land ceded by the Xhosas, forming a new village named Queenstown. Eli Wiggill applied for a farm in this new territory and was granted land at the head of the Komani River, where an old mission station was located. He also bought a corner lot in Queenstown, where he built his home. When Elder Walker arrived to preach in the area, George Wiggill compared Walker’s teachings with the scriptures and found that they “corresponded well with the New Testament Doctrine, so he came to the conclusion that it was worth studying.” Elder Walker stayed with George for several weeks, preaching and explaining his doctrines to all who would listen. George brought Elder Walker seventy miles to see Eli because Eli had been a preacher, so George wanted to hear his opinions regarding the Mormon missionary’s teachings. Eli met them on February 23 and took them home, conversing about this new religion the entire eight miles. Once they got back to his farm, Eli invited his neighbors to come hear Elder Walker preach, but only a few came to satisfy their curiosity. Eli commented that Walker’s discourse was “principally on Baptism, which impressed me. He also talked on Divine Authority. His language was so plain that any schoolboy could have understood him.” [26]

Eli Wiggill spent time investigating the Latter-day Saint faith and asked many questions, “all of which were answered satisfactorily” by Elder Walker. He received a copy of the Book of Mormon from Walker and recounted, “Its pages were full of interest and all its doctrines in accordance with Bible truths.” Parley P. Pratt’s The Voice of Warning pamphlet astonished Eli, and he was impressed with Elder Walker’s friendship with Joseph Smith and with how Walker personally vouched for Joseph’s noble character and pure life and attested to his cruel murder. Not long after they left and went back to Grahamstown, the Wiggill brothers and Elder Walker went to Fort Beaufort to teach, and Eli heard the Mormon hymns sung for the first time. Although Walker wanted to baptize him while they were there because he was “firmly convinced” that Eli believed the gospel to be true, Eli told him that he wanted to investigate more before making a decision. [27]

After the visit, and upon his return trip to Queenstown, Eli Wiggill said his mind was “full of this wonderful religion,” and noted, “And as I rode along, I seemed filled with a light and knowledge which illumined every page of the Bible as text after text flashed into mind. On arriving home, my wife said: ‘I believe you are converted to “Mormonism” already.’ Eli devoted every leisure moment to studying the books and pamphlets he received from Walker and recounted that he “could not help telling my friends and neighbors of Mormonism, and thus I gained their ill-will, My wife felt very bad to have our friends treat us coldly. So I put all the books on a high shelf, and decided not to read them any more.” But the spiritual feelings he had experienced were too poignant for him to ignore or dismiss. “At last I pulled the books down again and once more began to read them. I found them more interesting than ever, and the Lord opened my eyes to see every truth they contained.” Yet he decided to continue to study the teachings of the Church without formally becoming a Latter-day Saint. [28]

Missionaries Return to America with Emigrant Saints

At a conference held at Port Elizabeth on August 13, 1855, the Church in the Cape of Good Hope Mission consisted of three conferences, six branches, and a total membership of 126. In the fall of 1855, with their missions drawing to a close, Haven, Walker, and Smith began raising money to aid South African Saints to immigrate to America. The Latter-day Saint notion of gathering believers into one place had gained momentum in 1849 with the establishment of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund (PEF), which was designed to provide economic aid to converts throughout the globe to journey to Zion. Proselytizing and gathering became synonymous. President Brigham Young declared in 1860 that emigration “upon the first feasible opportunity, directly follows obedience to the first principles of the gospel we have embraced.” [29]

But gathering home to Zion for the South African Saints meant a long oceanic voyage that cost £15 to £20 ($70 to $95). [30] It also required the cooperation of ship captains. When several ship captains in South Africa formed a pact wherein they agreed not to transport Mormons, Port Elizabeth Saints John Stock, Thomas Parker, and Charles Roper shocked the countryside by selling their sheep and raising £2,500 ($11,875) to purchase their own ship, a 169-ton brig named the Unity. On November 28, 1855, Elders Walker and Smith, ten adult Saints, and five children set sail from Port Elizabeth to London aboard the vessel. This represented the first of a dozen voyages from Port Elizabeth on various ships that carried South African Saints to America. Between 1855 and 1865, at least 278 South African Saints emigrated from Port Elizabeth before ending their journey in Utah Territory. [31]

While these emigrating Saints strengthened the growth and prosperity of the Church in America, their leaving impeded the growth of the Church in South Africa because it drained strength from the fledgling branches. Every time the Church started to grow, many of the most devoted and stalwart members of the congregation boarded a ship and sailed to America, often accompanied by missionaries returning home, like Elders Walker and Smith. President Haven was one of the few missionaries who returned to America by himself. Before he left, the mission president sent an “Epistle to the Saints in the Cape of Good Hope Mission” to the various branches. He entrusted the Port Elizabeth Saints to the care of a local elder, Edward Slaughter, and the Cape Colony Saints to local elder Richard Provia. On December 15, 1855, Haven embarked for America aboard the Cleopatra. The first three missionaries had baptized 176 persons, some of whom had emigrated and a few others who had been cut off, leaving 121 Saints in the colony. [32]

While aboard the ship, Haven drafted a report of his mission to the Church’s First Presidency, consisting of Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Jedediah M. Grant. Haven reported, “I feel that the Lord has blessed us. The foundation of a good work has been laid in this land and a seed has been sown.” He continued, “We have taken men and ordained them Elders and appointed them to preside over the Saints we have left behind; and I believe these men will prove faithful, acting up to the best light they have.” He concluded his report by confiding, “It is not so easy a matter as one might suppose at first thought to establish the Gospel in a country where it has not before been established, where the climate weakens the constitution, . . . where the people speak three or four different languages and where they are all kinds, grades, conditions, casts, and complexions; and where only two or three hundred thousand inhabitants are scattered over a territory twice as big as England.” He also indicated that the Saints were eager to have more missionaries sent to South Africa. [33]

It would be several years before more elders did arrive. In 1857, Elder Ebenezer C. Richardson was sent from the British Mission to preside over the Cape of Good Hope Mission. Joseph Smith had baptized Richardson in 1834. President Richardson was accompanied by Elder James Brooks. The duo went to work reviving the branches, strengthening the Saints, and preaching the gospel. They rebaptized fifty-four earlier converts and baptized ten new members. This reformation infused new life into the fledgling branches. They instituted the law of tithing, emphasized the spirit of the gathering, and established a penny fund to raise money for the Perpetual Emigrating Fund. On April 24, 1858, fifty-five Saints boarded the Gemsbok and departed from Port Elizabeth, sailing for Boston. The LDS Church in South Africa numbered 243 members, who were once again left to the supervision of local leaders. [34]

John Wesley, a former Methodist Preacher from Cape Town who joined the new faith and became a missionary, traveled with Walker to the Eastern Cape to preach. Long-time investigator Eli Wiggill had many conversations with him since they had Methodism in common. After years of investigating and enduring persecution because his employer thought he had been “deluded by the Mormons,” Eli and his wife and a daughter were baptized by John Green on March 1, 1858. “Joy filled my soul,” Wiggill recorded, “as I was confirmed a member and ordained a Priest of the Church.” [35]

After their baptism, the Wiggills truly learned what it meant to be shunned by their friends. Many showed up to debate Wiggill, but he confounded them all with his knowledge of the gospel. One preacher capitulated, saying, “It is no use to talk with you, for you know the Bible from end to end.” The rest of Wiggill’s family was baptized in June 1858. After a thunderstorm destroyed his farm, Wiggill recounted how he “began to feel that I must gather with the Saints, and to reflect on pulling stakes and departing for Zion.” He sold his farm for £1,020 ($4,845) in bills. While making preparations to leave, Eli shared preaching duties with Henry Talbot. They left Queenstown for Port Elizabeth in April 1860. [36]

When they arrived in Port Elizabeth on May 14, 1860, Wiggill was appointed branch president. He was “well employed in acting as a teacher, visiting the sick and poor, and other Church duties. It was very comfortable and we got the people more united.” He also worked at gathering monies for the Perpetual Emigrating Fund and at preparing a group of Saints to travel to America. Wiggill engaged passage to America for his family and friends on the Race Horse, a three-masted barque bound for Boston. After nearly a year of Church service in Port Elizabeth, they awaited the arrival of new missionaries from Utah Territory who had been detained in England. No American missionaries had arrived in South Africa since Ebenezer Richardson and James Brooks had departed in 1858. On February 20, 1861, unable to wait any longer for more missionaries to arrive, they bade their friends farewell and boarded the Race Horse. Wiggill wrote, “Our company consisted of myself, and wife, two sons and three daughters, my son-in-law, George Ellis, his wife and three children; Mr. Henry Talbot, wife and large family, his son, Henry Jun., wife and child, making in all thirty souls.” In addition, a young Xhosa boy named Gobo traveled with the Talbot family. [37]

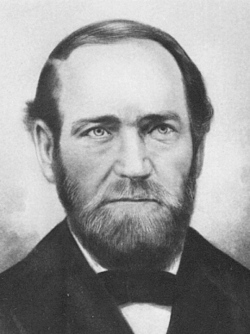

More American missionaries finally arrived at the Cape in December 1861. William Fotheringham was appointed mission president. Other missionaries included Elders John Talbot and Henry A. Dixon, two South Africans who had immigrated with their families to Utah but who returned to the land of their nativity on missions; Elder Miner C. Atwood; and Dutch-speaking Elder Martin Zyderlaan. These were the last Mormon missionaries to travel to South Africa in the nineteenth century. The Cape of Good Hope Mission was also renamed the South African Mission.

President Fotheringham assigned Elders Talbot and Dixon to serve with him in the Eastern Cape and requested Elder Zyderlaan labor among the Dutch/

Miner C. Atwood, a South African native who had immigrated to Utah, was one of the missionaries called to return to South Africa in 1861. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Miner C. Atwood, a South African native who had immigrated to Utah, was one of the missionaries called to return to South Africa in 1861. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

After arriving in Port Elizabeth, President Fotheringham and his fellow servants found the Church in the Eastern Cape in disarray. He wrote, “I find from a day’s experience in this place the few that profess to be saints are so divided, and destitute of the one spirit that you could not get them to come together on a ten acre lot. We have been visiting a few of them and with the help of God trying to instill in them the spirit union and love.” [40] Meanwhile, Elder Zyderlaan did not have much success proselyting among the Afrikaners. Eventually, he baptized one emigrant from Holland.

Meanwhile, Elder Dixon and local missionary Adolphus Noon embarked on the steamer Norman on February 25, 1863, to preach the gospel and establish the Church in Natal. They arrived on April 23 and commenced the work, preaching in the two largest cities in that colony—Durban and Pietermaritzburg. Like the first LDS missionaries who served in the Cape Colony a decade earlier, Dixon and Noon also faced hecklers, mobs, and little support from the local magistrates and constables. Once, a mob released a red-faced monkey to attack the elders, but they were unharmed. Nevertheless, Dixon recorded in his journal that “we found there was no law for the Mormons.” In a lengthy diatribe he expressed his frustration with the persecution: “Darkness seems to reign throughout this land of Ham. I feel we have done our duty faithfully in warning this people. I have been in Natal about seven months. South Africa is a hard country to labor in. . . . I have had but little success as yet in baptizing, and I realize that we may preach to the people but cannot make Saints of them.” [41]

To make matters worse, Elder Dixon had spent the entire previous year visiting, conversing with, and teaching family and friends in Uitenhage, a town seventeen miles inland from Port Elizabeth. In particular, he wanted to make peace with his father and mother, who were not pleased he had joined the Church at age twenty-one, immigrated to America, and now returned as a missionary without purse or scrip. Dixon’s grandfather was the Reverend William Boardman, the first colonial minister of the Church of England, and Dixon’s parents were troubled that their son had forsaken his family’s faith. His parents helped support him financially during 1862, but by December they parted ways. Dixon felt he had “done [his] duty to them” in his reconciliation efforts. Soon afterwards, he embarked to Natal to share the gospel. [42]

President Fotheringham, too, was getting discouraged with the slow progress of the Church in South Africa. In a letter to the European Mission president, George Q. Cannon, he lamented, “It is now bordering on two years since our arrival in the colony. . . . I feel it is my duty to lay before you the present situation of things as they exist in this land of Ham, without leaning particularly to one side or the other, then you will be able to form your own conclusions.” He then related, “From the letters I receive from my brethren and my own experience, I feel safe in saying that the inhabitants of South Africa are very well satisfied with the institutions of Babylon at present. There is a rankling, deadly hatred in their bosom against the truth and a determination on their part not to receive it.” [43] Grahamstown, for instance, contained the second largest population next to Cape Town, but the elders found they could not establish a branch there because the “inhabitants of this colony, Dutch and English, are completely under the influence of priestcraft.” [44]

The missionaries eventually returned home, accompanied by South African Saints gathering to Zion. On March 31, 1863, Elder Zyderlaan and thirty-one Saints boarded the Henry Ellis and set sail for New York. South African newspapers like the Colesberg Advertiser reported these departures, saying, “A ship has again left Port Elizabeth, Cape Colony, South Africa, destined for New York, with a number of new members of the Mormon Sect on board, who are all travelling to the town on the Salt Lake. Altogether there were 32 of them, amongst which were 25 adults.” [45] The following year, Elder Talbot took a group of eight on the Echo on April 5, 1864. President Fotheringham and Elder Dixon left with sixteen Saints aboard the Susan Pardeau on April 10, 1864, leaving Elder Atwood in charge as mission president. [46]

Elder Atwood held his own farewell on Sunday, April 9, 1865. He was unanimously chosen by the “vote of the saints to be the president of the company of saints about to leave for Utah.” He commented there was a “good spirit manifest among all. I counseled those remaining behind to meet together and sing and pray, but not to officiate in any of the ordinances of the gospel.” A few days later, on April 12, 1865, Elder Atwood and a company of forty-seven Saints sailed from Port Elizabeth on the Mexicano bound for Zion. [47]

Governmental restrictions, difficulties with the language, isolation from Church headquarters, persecution over polygamy in America and abroad, and the immigration of members to Utah all contributed to the discontinuance of the South African Mission on April 12, 1865. Although American missionaries had taken the lead, local missionaries played an important role in helping the Church grow. When the last American missionaries departed, a large company of Saints immigrated to Utah, and those remaining were left in the care of local Church leaders. Thirty-eight years elapsed before President Warren H. Lyon arrived and reopened the South African Mission on July 25, 1903. In spite of the long lapse, the missionaries that arrived—Elders William R. Smith, George A. Simpkins, and Thomas L. Griffiths—found that the seeds President Haven and his fellow servants had sown still bore fruit. A small number of Church members remained faithful in the gospel around Cape Town and in the Eastern Cape. [48]

Over the next hundred years, the Church grew slowly but steadily. Church Presidents and General Authorities began visiting South Africa. President David O. McKay was the first to do so, arriving in Johannesburg in 1954, one hundred years after Jesse Haven had opened the Cape of Good Hope Mission. The Transvaal Stake was created in 1970, the first in Africa. In 1973, President Spencer W. Kimball visited the stake and rededicated the land for the preaching of the gospel and for preparation for a future temple. Five years later, in 1978, he received a revelation granting the priesthood to all worthy male members of the Church, which had a tremendous impact on the growth of the Church in South Africa and throughout the continent. On August 24, 1985, the Johannesburg South Africa Temple was dedicated. Latter-day Saint Church membership in Africa reached one hundred thousand in 1997. After 150 years, South Africa boasted thirty-five thousand members and ten stakes in 2003. As of 2012, nearly fifty thousand Church members reside in South Africa, with three missions headquartered in Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town. [49]

Table 1 [50]

| Elders from America | Years | Dates Served as Cape of Good Hope Mission President |

| Jesse Haven | 1852–55 | April 18, 1853, to December 15, 1855 |

| William H. Walker | 1852–55 | |

| Leonard I. Smith | 1852–55 | |

| Local members in charge of missionary work | 1856–57 | |

| Ebenezer C. Richardson | 1857–58 | Autumn 1857 to April 24, 1858 |

| James Brooks | 1857–58 | |

| Local members in charge of missionary work 1859–60 | ||

| Name changed to South African Mission in 1862 | ||

| William Fotheringham | 1861–64 | December 1861 to summer 1864 |

| John Talbot* (South African) | 1861–64 | |

| Henry A. Dixon* (South African) | 1861–64 | |

| Martin Zyderlaan | 1861–63 | |

| Miner G. Atwood | 1864–65 | Summer 1864 to April 1865 |

| Local members in charge of missionary work 1865 to 1903 | ||

| Local missionaries who served between 1853 and 1903 include John Green, George Kershaw, Adolphus Noon, William Priestley, Richard Provis, Joseph Rands, Edward Slaughter, John Stock, John Talbot, Thomas Tredgidga, Thomas Weatherhead, John Wesley, Eli Wiggill, and Charles Wood. | ||

| Warren H. Lyon reopened South African Mission in 1903 | ||

Notes

[1] Leonard Thompson, A History of South Africa, 3rd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 31–69; J. D. Omer-Cooper, History of Southern Africa, 2nd ed. (London: James Currey, 1994), 17–51. I have retained the original spelling of quotations drawn from primary sources throughout. I am grateful to my research assistant, Aaron Cobia, who helped compile some of the information for this essay. I appreciate the suggestions of colleagues James B. Allen, Herman du Toit, Spencer Fluhman, and Leslie Hadfield and of the peer reviewers. Finally, I thank the editors, Fred E. Woods and Reid Neilson, for their encouragement and support.

[2] William W. Bird, comp., State of the Cape of Good Hope, in 1822 (London: John Murray, 1823; facsimile reprint, Cape Town: C. Struik, 1966), 178–243; H. E. Hockly, The Story of the British Settlers of 1820 in South Africa (Cape Town: Juta, 1948). The 1820 settlers and their contributions are commemorated in Grahamstown in the 1820 Settlers National Monument, which opened in 1974. A living monument, it hosts plays, musical performances, and cultural events (see British 1820 Settlers to South Africa, http://

[3] H. C. Bredekamp and Robert Ross, eds., Missions and Christianity in South African History (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1995); John S. Galbraith, Reluctant Empire: British Policy on the South African Frontier, 1834–1854 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963), 79–97; J. G. Pretorius, The British Humanitarians and the Cape Eastern Frontier, 1834–1836 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1988); Robert C. H. Shell, Children of Bondage: A Social History of the Slave Society at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652–1838 (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, for Wesleyan University Press, 1994); Richard Elphick and Rodney Davenport, eds., Christianity in South Africa: A Political, Social, and Cultural History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

[4] Piet Retief, “A Trek Leader Explains Reasons for Leaving the Cape Colony, 1837,” in George von Welfling, ed., Select Constitutional Documents Illustrating South African History (London: Routledge, 1918), 144–45; Eric Walker, The Great Trek (London: Black, 1948); Norman Etherington, The Great Treks: The Transformation of Southern Africa, 1815–1854 (New York: Longman, 2001). One of the most significant conflicts between Africans and Afrikaners occurred on December 16, 1838, at the Battle of Blood River, wherein the Afrikaners entered into a covenant with God to serve him if he would help them win the battle. They defeated Dingane’s Zulu army and avenged the death of Piet Retief. December 16 is commemorated as a religious public holiday known as the Day of the Vow or, since 1994, the Day of Reconciliation. It has played an important role in fostering strains of Afrikaner nationalism and identity. See Donald H. Akenson, God’s People: Covenant and Land in South Africa, Israel, and Ulster (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992). Afrikaans, a derivation of high Dutch, became a distinct language during the first half of the nineteenth century. Afrikaans is the mother tongue of approximately 60 percent of South Africa’s white population. See T. Moodie, The Rise of Afrikanerdom: Power, Apartheid, and the Afrikaner Civil Religion (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975).

[5] Joseph Smith diary entry recorded by Willard Richards on April 19, 1843. B.H. Roberts, ed., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 5:368.

[6] Jesse C. Haven (March 28, 1814–December 13, 1905) traveled west with his family with the Edward Hunter Company in 1850. William H. Walker (August 28, 1820–January 9, 1908) was a member of the Mormon Battalion Sick Detachment and traveled to Utah in 1847. Leonard I. Smith (October 18, 1825–July 25, 1877) traveled to Utah Territory with his wife Ann in 1851. It is likely that none of the three attended the meeting when their names were announced. The revelation on polygamy, now recorded in Doctrine and Covenants 132, was attached as “Supplement, 1853,” Millennial Star, January 1, 1853, 5–8. For discussion of the 1850s defense of polygamy, see David J. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Polygamy Defenses,” Journal of Mormon History 11 (1984): 43–63.

[7] “The Daily Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, January 3, 1853, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Haven recorded that on December 29 a terrible storm arose that the captain said was the worst he had seen in twenty years. It nearly destroyed the ship, and Haven was convinced that the presence of the elders on board and the prayers they offered kept the ship from sinking. See “The Daily Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, December 29, 1852.

[8] Missionary Journals of William Holmes Walker: Cape of Good Hope South Africa Mission, 1852–1855, ed. Ellen Dee Walker Leavitt (Provo, UT: John Walker Family Organization, 2003), 17; William Holmes Walker, The Life Incidents and Travels of Elder William Holmes Walker and His Association with Joseph Smith the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Elizabeth Jane Walker Piepgrass, 1943; reprinted by the John Walker Family Organization, 1971). After they had embarked on February 11, the trio retired to their bedrooms and all prayed. Haven blessed Walker and Smith, and Walker and Smith blessed him. They felt perfectly united and that the Spirit of God was with them. They prayed for favorable winds and a speedy passage to their destination. See “The Daily Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, 42–43. When they arrived at Cape Town, Haven wrote, “Apr. 18th . . . Nearly a calm this morning. Wind breezed up a little afternoon; so we were able to go into the Bay. In the evening very pleasant. Anchored about one mile from the town. The town lies in nearly under a mountain. mountains all round. Apr. 19th . . . Came off the ship into Cape Town.” Walker, Missionary Journals, 63.

[9] Walker, Missionary Journals, 18. Millennial Star, January 22, 1853, 58, 115, 160, 410.

[10] “Apr. 25th . . . The assembly done very well till Bro. Smith got up and spoke of Joseph Smith being sent of God and of the Book of Mormon being a divine revelation; they then made so much disturbance that we were obliged to dismiss.” “Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, 64–65; Walker, Missionary Journals, 20. Haven wrote a letter regarding the first month’s activities that was published in the Millennial Star: “Elder Haven spoke on the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. Great confusion prevailed, and he had much difficulty in making himself heard. The following evening, a meeting was attempted, but the mob made so much confusion, that the meeting was broken up. The brethren determined not to hold any more public meetings, for a time, and concluded to do what could be done by circulating tracts, private conversation, &c. Some preachers had begun to deliver lectures in opposition. On the 10th of June, the brethren tried to hold another meeting, but the mob soon broke it up, threatening them. Friends were springing up, inquiring after the truth, and a few seemed ready for baptism. One person had had a vision concerning the work. An extensive order for Books of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and other publications, was enclosed in Elder Haven’s letter.” Millennial Star, July 23, 1853, 475.

[11] “Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, 65–66; Walker, Missionary Journals, 21.

[12] Walker, Missionary Journals, 22–25.

[13] An example of the anti-Mormon literature of the period is a Dutch pamphlet written by the Reverend J. Beijer, minister of the Dutch Reformed Church in the Orange Free State, entitled De Mormonen in Zuid-Afrika and published in 1863. He opposed the Mormon religion, their missions, and their proposed university and lamented, “The Mormons, who have their headquarters in North America, are not along active there, but . . . they even work unashamed in South Africa to gain proselytes.” Title page reprinted in Eric Rosenthal, “Mormons in Africa,” Stars and Stripes in Africa (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1938), 101–3.

[14] David J. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Imprints in South Africa,” BYU Studies 20, no. 4 (Summer 1980): 404–16.

[15] “May 26th . . . A little past sunset bro. Smith baptized Joseph Patterson and John Dodd. We then went to bro. Dodd’s shop and confirmed them.” “Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, 71–74. Rondebosch resident Henry Stringer was baptized by Elder Smith on June 15, 1853. Eight days later, Nicholas Paul was baptized. Paul, a thirty-year-old builder and an influential member of the community, aided the missionaries greatly and was called the following November to be the Mowbray branch president. The Newlands Branch was formed on September 7, 1853, with Thomas Weatherhead as branch president. Up to that time, about fifty persons had been added to the Church by baptism. Elder Haven said, “The majority of the converts are the meek and the poor.” For a detailed record of the Mowbray Branch’s history, meetings, funding, membership, ordinations, and records, see South Africa Mission, Mowbray Branch Record, vols. 1 and 2, 1853–69, Church History Library. For a record of the entire western Cape during this period, see South Africa Mission, “Cape Conference, Historical Record, 1853–1890,” Church History Library.

For a general overview of the mission, see Farrell R. Monson, “History of the South African Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1853–1970” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1971); Evan P. Wright, “A History of the South African Mission, 1852–1970,” 3 vols. (n.p., 1977–86).

[16] Jesse Haven to Samuel W. Richards, Liverpool, August 20, 1853, and January 20, 1854; South Africa Mission, “Manuscript History,” vol. 1, Church History Library; Millennial Star, March 18, 1854, 173.

[17] “Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal A, 95–140; “Journal of Jesse Haven,” Journal B.

[18] Jesse Haven to Brigham Young, November 1, 1854, in South Africa Mission, “Manuscript History,” vol. 1, Church History Library.

[19] The Book of Mormon was eventually translated into Dutch (Het Boek van Mormon; 1890), Afrikaans (Die Boek van Mormon; 1972), Xhosa (Incwadi ka Mormoni; 2000), and Zulu (Incwadi Kamormoni; 2003). The first Afrikaans-speaking LDS missionaries arrived in South Africa in 1963.

[20] “Journal of Jesse Haven,” January 24–29, February 12–16, 1855, Journal B, 348; Jeffrey G. Cannon, “Mormonism’s Jesse Haven and the Early Focus on Proselytizing the Afrikaner at the Cape of Good Hope, 1853–1855,” Dutch Reformed Theological Journal 48, nos. 3–4 (September and December 2007): 446–56.

[21] This changed in 1978 with the revelation given to President Spencer W. Kimball that allowed the priesthood to be conferred upon any worthy male, which increased LDS proselyting activities throughout Africa. See Official Declaration 2. E. Dale LeBaron, who served as the South Africa mission president in 1978, later recounted the importance of the 1978 priesthood revelation. See E. Dale LeBaron, oral history, interview by Matthew K. Heiss, March 10, 1989, Church History Library; Andrew Clark, “The Fading Curse of Cain: Mormonism in South Africa,” Dialogue 27, no. 4 (Winter 1994): 41–56.

[22] Wright, “A History of the South African Mission, 1852–1970,” 1:96–97. Haven praised the work Smith was doing by saying that he was “first rate to break new ground; he likes to visit the Priests of the day, and the way he manages them and their flocks wonderfully disturbs their equilibrium.” Jesse Haven’s report on the mission, written to the First Presidency of the Church in June 1854 while onboard the ship Cleopatra, South African Mission History, Church History Library.

[23] The Port Elizabeth Mercury would not publish Elder Walker’s tracts, but the Port Elizabeth Telegraph did. William Holmes Walker, To the Intelligent Public (1854). He had five hundred copies of the broadside published. See Millennial Star, March 15, 1856, 172–73; David J. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Imprints in South Africa,” BYU Studies 20, no. 4 (Summer 1980): 408.

[24] Noel Mostert, Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People (New York: Knopf, 1992); Timothy J. Stapleton, Maqoma: Xhosa Resistance to Colonial Advance, 1794–1873 (Johannesburg: J. Ball, 1994), 133–37, 144–45.

[25] “Eli Wiggill Autobiography,” 22–23, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Eli Wiggill (November 5, 1810–April 13, 1884), also spelled Wiggall and Wiggell, was a convert from Eastern Cape. He eventually served as the branch president in Port Elizabeth. He was one of only a few South African converts to keep an extensive journal, both before and after his conversion to the Church. I thank Nancy and Mike Wiggill for their assistance with finding additional information about, and images of, Eli Wiggill and his family. See “Eli Wiggill,” in An Enduring Legacy, comp. Kate B. Carter (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1985), 8:169–212.

[26] Wiggill, “Autobiography,” 26; Walker, Journal of William Walker, 161. Elder Walker’s journal discusses his missionary labors in Grahamstown, Fort Beaufort, Alice, Uitenhage, and Port Elizabeth. Entries include his travels with fellow missionaries Jesse Haven and Leonard Smith and Church members such as John Wesley, Thomas Parker, Joseph Ralph, and Eli Wiggill.

[27] Wiggill, “Autobiography,” 26.

[28] Wiggill, “Autobiography,” 26.

[29] Brigham Young to Amasa Lyman, and others and Saints in the British Isles, August 2, 1860, Brigham Young Letterbooks, Church History Library.

[30] The approximate equivalent of the British pound in US dollars in the mid-nineteenth century was $4.75.

[31] The South African Saints aboard the Unity arrived in London on January 29, 1856, the first Mormon emigrants from Africa. See Conway B. Sonne, Saints on the Seas: A Maritime History of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 18, 80–81; E. Dale LeBaron, “The Church in Africa,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: MacMillian, 1992), 1:22–26; David F. Boone and Richard O. Cowan, “The Church in Africa,” in Unto Every Nation: Gospel Light Reaches Every Land, ed. Donald Q. Cannon and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 395–417. For details on the lives of some of these South Africa emigrants, see Sophie W. Schurtz, “South Africa’s Contribution to Utah,” in Treasures of Pioneer History, comp. Kate B. Carter (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1957), 6:237–300.

[32] Andrew Jenson, “The South Africa Mission,” Encyclopedic History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941). Haven arrived in America and led a handcart company across Iowa. At Florence, his handcart company was merged with the Martin Company. He began traveling in Hunt’s wagon company, and about September 1, 1856, he began traveling in William B. Hodgetts’ company and arrived in Utah in December. The Martin Handcart Company was too late in their journey, and Brigham Young sent out a rescue party to bring the pioneers safely home after their terrible winter ordeal.

[33] Millennial Star, March 22, 1856, 189; Jesse Haven, “Report to the First Presidency, January 1856,” unpublished manuscript by Jeffrey G. Cannon.

[34] Millennial Star, April 24, 1858, 619; William Fotheringham, “Diaries, 1854–1910,” Church History Library. The conference held in Port Elizabeth on July 11, 1858, had nineteen elders, five priests, five teachers, two deacons, and 212 total members.

[35] Wiggill, “Autobiography,” 27. Wesley (1831–1909) joined the Church in 1853, became a local missionary from 1855 to 1858, and emigrated to Salt Lake in 1859. See John E. Wesley, “Diaries” (ca. July 1857 to January 1859), Granite Mountain Record Vault, Salt Lake City.

[36] Wiggill, “Autobiography,” 27, 29.

[37] Wiggill, “Autobiography,” 30. After settling in Utah, Wiggill’s beloved Susannah died. After Wiggill remarried, he took the opportunity to visit South Africa and made wagons for prospectors heading to the diamond fields of Kimberly in the late 1860s and early 1870s. With the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, people in Chicago accused the Talbots of owning a slave, so they disguised Gobo as a girl for the rest of his train ride. Upon arriving in Utah Territory, Gobo worked as a sheepherder and eventually became a prosperous sheep raiser in Idaho before his tragic death in 1886. See H. Dean Garrett, “The Controversial Death of Gobo Fango,” Utah Historical Quarterly 57, no. 3 (Summer 1989): 264–72. For information on the Talbot family, see “Historical Data on the Talbot Family, 1932,” L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[38] “A Revelation and Prophecy by the Prophet, Seer, and Revelator Joseph Smith: Given December 25th, 1832. [Doctrine and Covenants 87]” (Cape Town: s.n., 1863), L. Tom Perry Special Collections; also in the Church History Library.

[39] William Fotheringham, “Diaries, 1854–1910,” February 10, 1862, Church History Library.

[40] Fotheringham, “Diaries, 1854–1910,” July 11, 1862, Church History Library.

[41] Henry A. Dixon, “Diary of Henry Aldous Dixon [1835–1884], August 1861–August 1863,” 93–126, L. Tom Perry Special Collections; excerpt printed in the Millennial Star, December 19, 1863, 812–15.

[42] “Diary of Henry Aldous Dixon, August 1861–August 1863,” December 1862, 78; see also 19–20, 34, 70–71, 77–78.

[43] William Fotheringham to George Q. Cannon, in South Africa Mission, “Manuscript History,” vol. 1, Church History Library.

[44] Printed in the Millennial Star, December 19, 1863, 812–15.

[45] Colesberg Advertiser, April 2 and 4, 1863.

[46] Wright, “A History of the South African Mission,” 1:264–80. For records, receipts, accounts, and inventories, see South Africa Mission, “Account Books, 1854–1863,” vols. 1 (1854–1859) and 2 (1859–1863); and South African Mission, “Port Elizabeth Branch Record, 1858–1864,” Granite Mountain Record Vault, Salt Lake City.

[47] Miner G. Atwood, “Journals [1857]–1865,” L. Tom Perry Special Collections; and “Excerpts from the Journal of Miner G. Atwood, 1861–65,” in South Africa Mission, “Manuscript History,” vol. 1, Church History Library. Crossing the plains, Atwood was placed in charge of a company of four hundred souls. West of Fort Laramie they were attacked by Indians, who wounded seven men and Mrs. Grundtvig. See B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1965), 5:96.

[48] South Africa Mission, “Manuscript History,” vol. 2, Church History Library.

[49] Andrew Jensen, “The South Africa Mission,” Encyclopedic History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941); R. Val Johnson, “South Africa: Land of Good Hope,” Ensign, February 1993, 32–42; Hiram and Anne McDonald, “Membership Reaches 100,000 in Africa,” Church News, January 18, 1997, 3; Julie D. Heaps, “South Africa Celebrates 150 Years,” Church News, September 6, 2003, 6; H. Dean Garrett, “South Africa,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Desert Book, 2000), 1160–61.

[50] South Africa Mission, “Manuscript History and Historical Reports,” vol. 1 (1853–87), Church History Library.