“Divert the Minds of the People”

Mountain Meadows Massacre Recitals and Missionary Work

Brian D. Reeves

Brian D. Reeves, "'Divert the Minds of the People': Mountain Meadows Massacre Recitals and Missionary Work," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 291–315.

Brian D. Reeves was a researcher-archivist at the Church History Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, when this article was published.

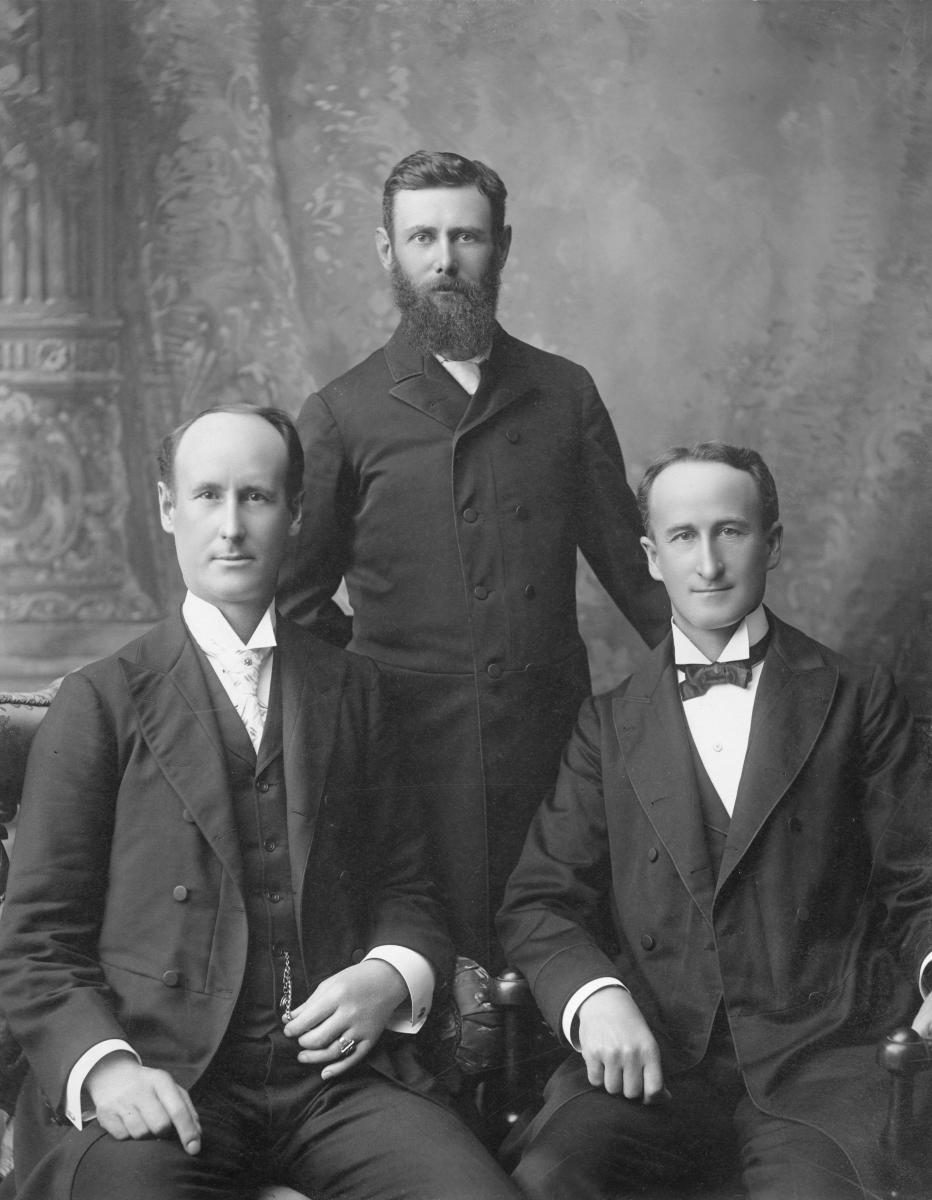

Figure 1. Left to right: J. Golden Kimball, Ben E. Rich, and J. Golden Kimball's brother Elias S. Kimball, ca. 1898. J. Golden Kimball served as president of the Southern States Mission from 1891 to 1894 and was succeeded in turn by Elias S. Kimball and Ben E. Rich. All images courtesy of the Church History Library unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1. Left to right: J. Golden Kimball, Ben E. Rich, and J. Golden Kimball's brother Elias S. Kimball, ca. 1898. J. Golden Kimball served as president of the Southern States Mission from 1891 to 1894 and was succeeded in turn by Elias S. Kimball and Ben E. Rich. All images courtesy of the Church History Library unless otherwise noted.

J. Golden Kimball presided over the Southern States Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1891 to 1894. On one occasion, before delivering a sermon in a city courthouse, he became concerned when he noticed that there were only men in the audience. “When there are no women there is a great deal of danger. It is dangerous enough when they are present.” As he started to preach, “All at once something came over me and I opened my mouth and said, . . . ‘Gentlemen, you have not come here to listen to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. . . . You have come to find out about the Mountain Meadows Massacre and polygamy, and God being my helper I will tell you the truth.’ And I did. I talked to them for one hour. When the meeting was out you could hear a pin drop.”

Later, at the hotel where he was staying, Kimball heard a brass band playing outside. He sent one of his missionaries to find out “what it all meant.” The elder “inquired and they told him: ‘We are serenading that big long fellow.’ That is the only brass band I have ever had dispense music after one of my talks.” The next day Kimball told his missionaries, “‘Don’t one of you dare preach that sermon; it will cost you your life.’ And I have never preached it since.” [1]

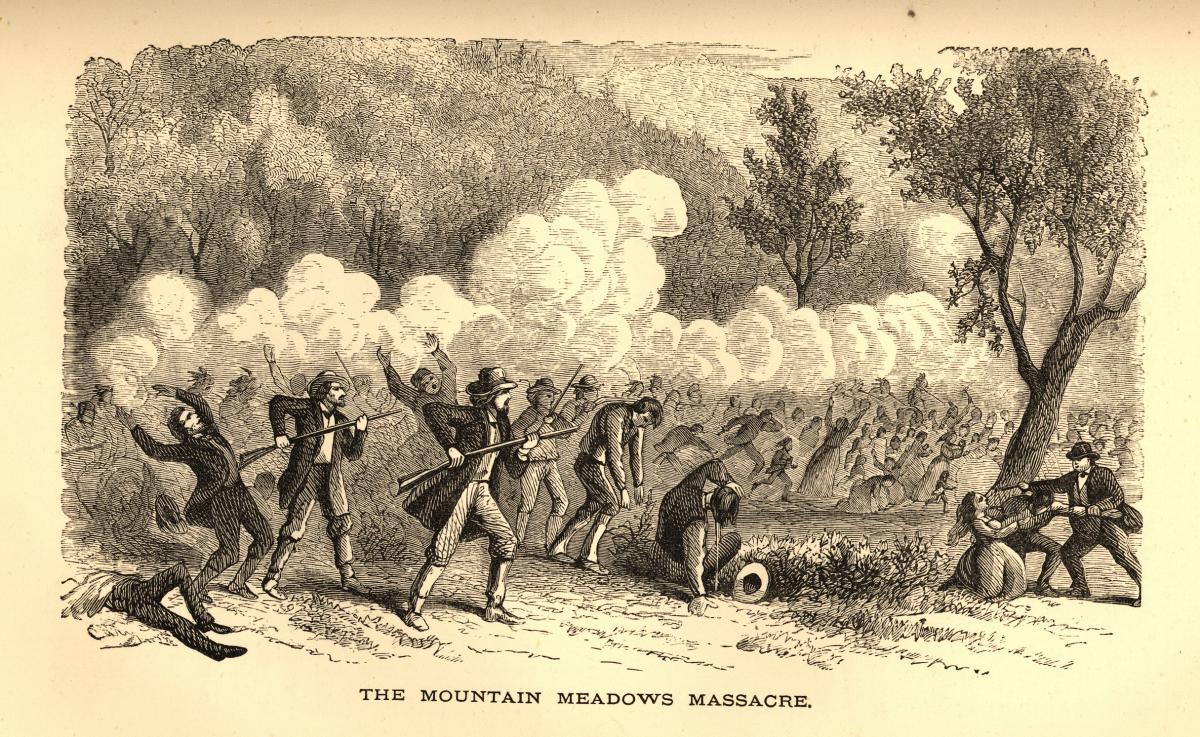

The Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred on September 11, 1857, in southern Utah, when most of the members of a company of Arkansas emigrants en route to California were murdered by Mormons and Paiutes. Approximately 120 men, women, and children were killed. Within a decade this event was woven into the fabric of anti-Mormon literature. This paper will identify prominent anti-Mormon works, mostly during the 1870s, that discussed the massacre and the impact that such works had on Mormon missionary efforts, especially in 1877 when John D. Lee was executed for his role in the crime.

John D. Lee Murder Trials

On September 24, 1874, Lee and eight others were indicted for murder by a grand jury in Beaver, Utah. The court issued a warrant for Lee’s arrest on October 13, and he was captured in Panguitch on November 9. Lee’s first trial, held in Beaver in July and August 1875, resulted in a hung jury. [2] Extensive newspaper coverage of the trial painted a negative picture of the Church. William C. Staines, the Church emigration agent in New York City, wrote to Brigham Young on July 27, 1875, saying, “I find since the . . . trial has commenced but little can be said to any body.” He noted that “newspaper reports of the trial, contain every thing they can against our people, making it appear as much as possible, that You and Your associates had more or less to do with it.” [3] Staines wrote again a few weeks later: “The Newspapers have had a great deal [to] say about the Lee trial,” and most of the articles favored “putting an end to ‘Mormonism.’” In Nevada the Pioche Daily Record editorialized on August 8, 1875, that the crime belonged “at the door of Brigham Young” and that “Mormonism has long since ceased to be a religion. It can be viewed as a species of compound felony.” [4]

The bad press subsided after the first trial. George Q. Cannon wrote from Washington, DC, in January 1876 that few paid much attention to Mormon news because “there are so many other questions of overshadowing importance.” But, he added, “as soon as the Devil begins to throw mud this will probably become less apparent.” [5] Lee’s second murder trial took place in September 1876. The national press noted his conviction, but the coverage paled in comparison to the extensive articles devoted to his execution and confessions six months later. [6]

Anti-Mormon Books

In the mid-1860s, anti-Mormon books began to include sections on the Mountain Meadows Massacre. In the following decade, the massacre became a staple in such works, generally playing second fiddle to the more popular polygamy theme. Sanford Bingham, a Latter-day Saint missionary, reflected as he completed his service in New England in 1877, “I beleave we have done some good in allaying prejudice and that some have been almost or quite convinced that our principles were true, yet through the dreadful lies that are published by Mrs Stanhouse [Stenhouse], J H Beadle and Ann Eliza [Young] . . . they are in fear that there is something behind the curtain which is bad.” [7]

In 1870, J. H. Beadle included a section on the massacre in his book Life in Utah; Or, the Mysteries and Crimes of Mormonism. He posed the question, “Did Brigham Young know aught of, or give command for this massacre? The strong probability of course, is, that he did not.” Contradicting his own assessment, Beadle then gave several reasons why Young might be guilty after all. According to one estimate, Beadle’s Life in Utah sold over seventy thousand copies in fewer than three years. [8] On July 4, 1872, Beadle interviewed John D. Lee at Lee’s home in Lonely Dell, near the Utah–Arizona border. Upon reading Beadle’s report of their interview in the Salt Lake Tribune, Lee wrote in his diary, “Although the account given was far from being correct, nevertheless it was nearer true then any other written account previously brought to light.” Beadle also included the Lee interview in his next book, The Undeveloped West (1873). [9]

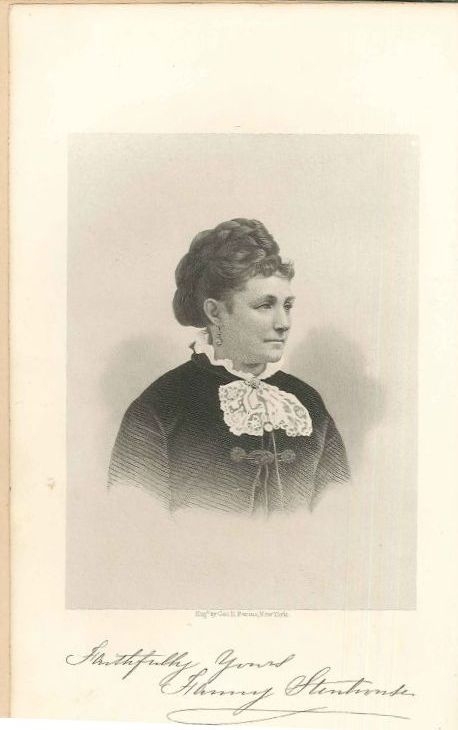

Figure 2. Pages from Fanny Stenhouse's second book, "Tell It All": The Story of a Life's Experience in Mormonism (1874).

Figure 2. Pages from Fanny Stenhouse's second book, "Tell It All": The Story of a Life's Experience in Mormonism (1874).

T. B. H. Stenhouse and his wife, Fanny, embraced Mormonism in the late 1840s and left the faith in 1870. [10] Two years later Fanny’s first book, Exposé of Polygamy in Utah: A Lady’s Life Among the Mormons, was published. [11] As the title suggests, it focused primarily on plural marriage. Her second book, “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism (1874), included roughly fourteen pages on the massacre (see fig. 2). She claimed that the crime was Mormon retribution for the murder of Parley P. Pratt in Arkansas and that George A. Smith had participated in a military council that decided to attack the emigrants. Both Pratt and Smith were Apostles in the Church. She wrote regarding Brigham Young, “I do not, of course, say that he gave the order for this accursed deed, but that it was his business to bring the criminals to justice.” [12] A second edition of “Tell It All” (1878) devoted an additional thirty pages to the massacre, including statements by John D. Lee and a brief account of his criminal trials and execution. [13]

In 1873, T. B. H. Stenhouse’s book, Rocky Mountain Saints, was published in New York (see fig. 3). Stenhouse spent thirty-five pages on the massacre. He quoted extensively from the pseudonymous “Argus” the disaffected Mormon Charles Wesley Wandell, and he also included the affidavit of massacre participant Philip Klingensmith. [14] Stenhouse called the massacre “the darkest crime on record in American history.” Addressing Brigham Young’s possible role, Stenhouse gave Young “the benefit of whatever uncertainty there is about the matter” but added that, “if he is innocent,” Young should clear his name by encouraging the investigation of the crime. [15]

The Stenhouses’ books were popular in the United States and abroad and were reissued several times over the next thirty years. [16] Utah congressional delegate George Q. Cannon reported in February 1873 that copies of T. B. H.’s book were “scattered around on the desks of Senators” in Washington. [17] The couple also affected public opinion in other ways, he through newspaper articles and she through public lectures in the United States and Australia. [18]

A missionary in Illinois reported to Brigham Young in January 1877 that among non-Mormons “the first question inverrable [invariably] are what about Poligamy and the mountain meadow macher [massacre] I meet with Ann [Eliza Young’s] Book and others of the same class also Mark Twains comical views. All of which are received as Gospel here.” [19] Popular American author Mark Twain briefly mentioned the massacre in his book Roughing It (1872), mostly quoting from earlier works by Catharine V. Waite and John Cradlebaugh. [20]

Figure 3. Image from T. B. H. Stenhouse's book Rocky Mountain Saints (1873), 426.

Figure 3. Image from T. B. H. Stenhouse's book Rocky Mountain Saints (1873), 426.

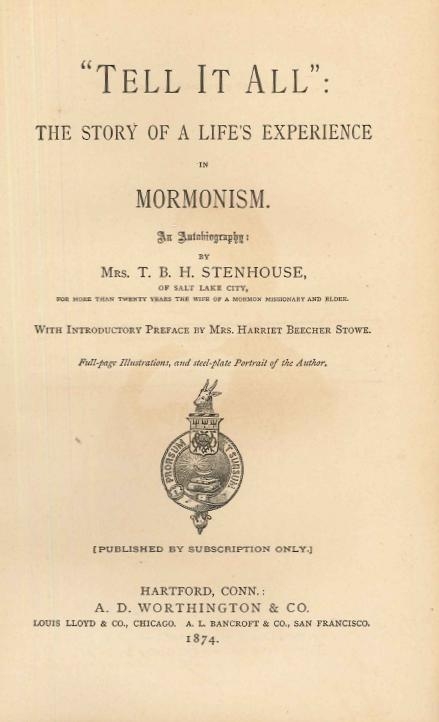

Ann Eliza Webb Young was a one-time plural wife of Brigham Young who left both him and the Church. Like Fanny Stenhouse, she traveled the lecture circuit in the United States giving talks against Mormonism. Her book, Wife No. 19, appeared in late 1875 (see fig. 4). She derived much of her massacre information from a newspaper report published earlier that year by Charles F. McGlashan, who had interviewed several southern Utah residents. [21] Ann Eliza wrote that Brigham Young “was, to all intents and purposes, the murderer of these people, and should be held responsible for their lives.” She repeated a rumor that Daniel H. Wells, Young’s counselor in the First Presidency, personally killed one of the children who had survived the massacre, adding, “I cannot vouch for the authenticity of this rumor, but those who know the man best are the most ready to believe it.” [22]

John D. Lee’s Statements

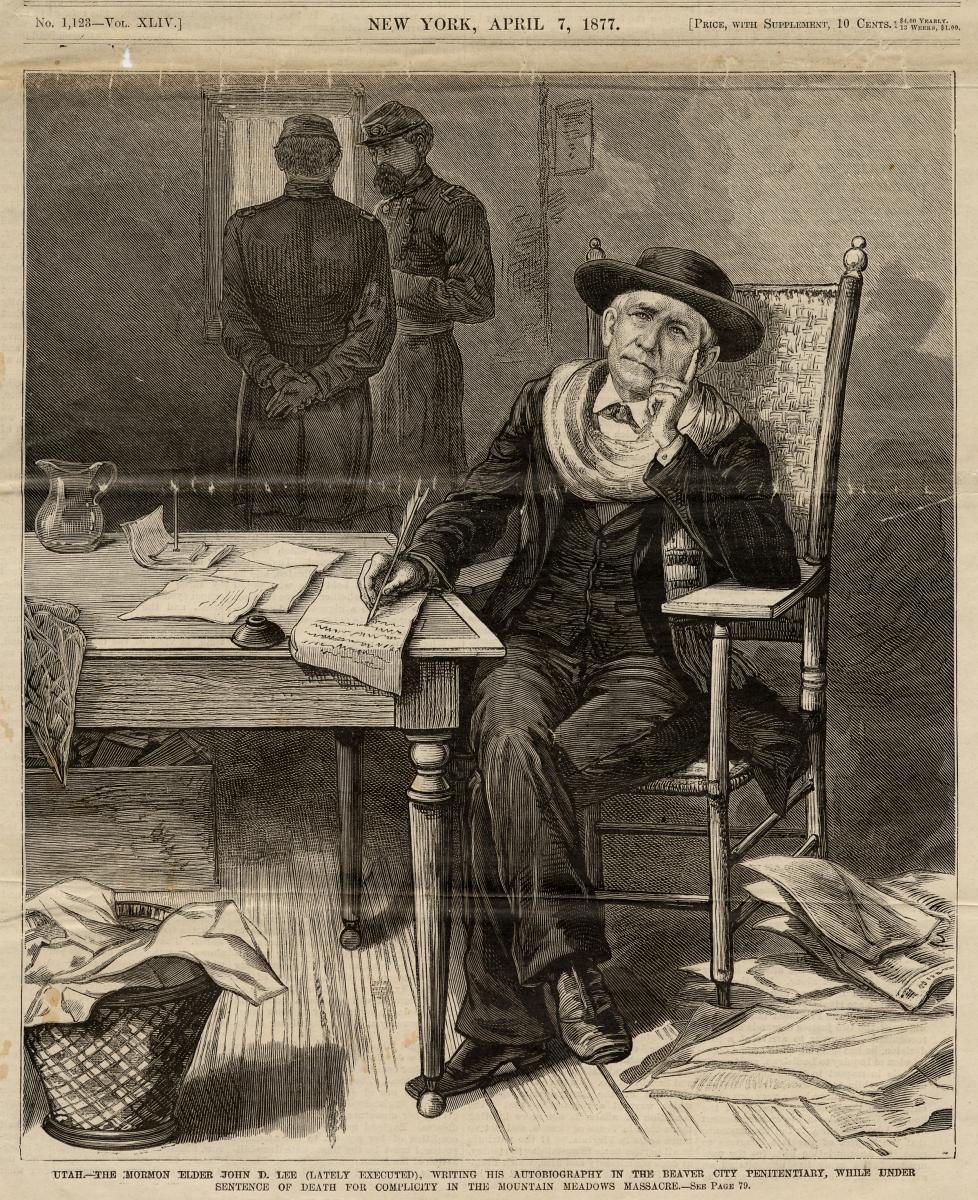

A missionary wrote from San Francisco in February 1877 that people showed little interest in Mormonism other than wanting to know “if John D. Lee is hanged yet.” That same month, with his execution just a month away, Lee gave to prosecuting attorney Sumner Howard a written statement about the massacre (see fig. 5). This statement and others attributed to Lee severely undermined the Church’s missionary efforts, especially in 1877, when they were first published. In the statement Lee gave to Howard, Lee made incriminating comments about Brigham Young and George A. Smith, but he also exonerated Young from the charge of having ordered the massacre. Lee wrote that after the first attack on the emigrants, a messenger “was sent with a dispatch to President Brigham Young, asking his advice about interfering with the company, but he did not return in time.” [23] Though Lee did not specify what Young’s response had been, in fact it was that Mormons “must not meddle with” the emigrants. [24]

Figure 4. Ann Eliza Young. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Figure 4. Ann Eliza Young. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

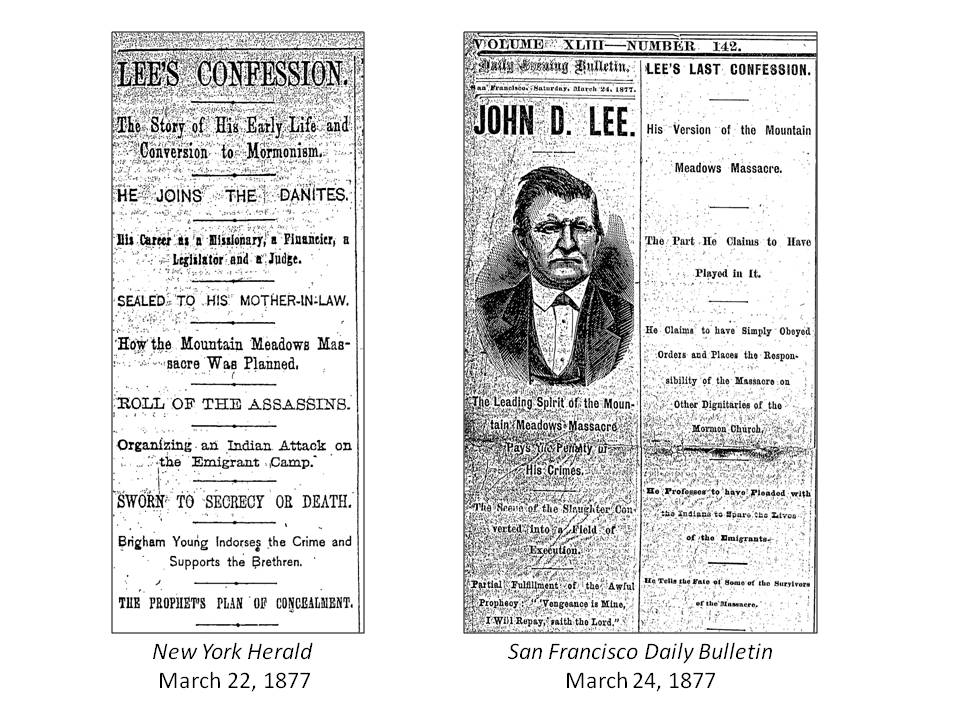

Lee’s defense attorney, W. W. Bishop, was chagrined to learn that his client had given a written statement to the prosecuting attorney, especially because Lee had previously signed over to Bishop the rights to his life story. Bishop wrote to Lee two weeks before the execution, saying, “Your confession given to Howard is having a bad effect so far as the sale of your writings are concerned, but by giving me your history during your life in Utah I can make the thing work all right yet I think.” [25] Bishop’s version of Lee’s confession appeared in the New York Herald and the San Francisco Chronicle on March 22, 1877, the day before Lee’s execution. It proclaimed that “the Mountain Meadows massacre was the result of the direct teachings of Brigham Young, and it was done by the orders of those high in authority in the Mormon community.” [26] The day before publishing the Bishop version of Lee’s confession, New York Herald editor James G. Bennett telegraphed to Brigham Young the following: “Herald publishes confession of Lee in which he accuses you of being directly responsible for the massacre at Mountain Meadows—Through your teachings.” [27] Young responded that if Lee had made such a charge, “it is utterly false. My course of life is too well known by thousands of honorable men for them to believe for one moment such accusations.” [28]

Figure 5. Illustration of John D. Lee writing his autobiography shortly before his execution, from Frank Leslie's Illustrated (April 7, 1877).

Figure 5. Illustration of John D. Lee writing his autobiography shortly before his execution, from Frank Leslie's Illustrated (April 7, 1877).

On March 24, the day after Lee’s execution, the statement he gave to Sumner Howard was published in the San Francisco Daily Bulletin, the New York Times, the New York Herald, and several other papers. Soon both versions of the Lee confession appeared in newspapers across the country (see fig. 6). [29] A few months later, Lee’s autobiography, edited by William W. Bishop and including an expanded version of his confession, was published as a book entitled Mormonism Unveiled; or The Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee; (Written by Himself) (see fig. 7). Bishop wrote that it was his duty to publish the work “to show that Mormonism was as certainly the cause of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, as it is that fanaticism has been the mother of crime in all ages of the world.” Mormonism Unveiled was a big hit. It went through nineteen printings between 1877 and 1892, suggesting sales of well over a hundred thousand copies. [30]

The extensive newspaper coverage of Lee’s execution and confessions, and the publication of Mormonism Unveiled, created a spike in anti-Mormon sentiment that temporarily crippled missionary work, especially in the northern United States. Brigham Young’s statement that honorable men would not believe the accusations made against him was drowned in a sea of anti-Mormon newspaper print. A week after Lee’s execution, Young and some associates spent an evening reading telegraphic news dispatches at his winter residence in St. George. The reports showed “the spirit of the Press. urging upon the nation the distruction of the Latter day Saints taking on an excuse the confession of John D. Lee in the complicity of Prest Young & other leaders in the M M Massacre.” [31] Parowan resident Joseph Fish observed that all of the newspaper reports “on the execution of Lee were unfavorable to the Mormon people.” He surmised that the press was making every effort “to prejudice the people against the people of Utah.” [32]

Figure 6. John D. Lee's statement printed in the San Francisco Daily Bulletin, March 24, 1877.

Figure 6. John D. Lee's statement printed in the San Francisco Daily Bulletin, March 24, 1877.

Backlash against Missionary Work

Missionaries in the United States keenly felt anti-Mormon backlash. One wrote from Pike County, Illinois, “The whole country is full of the most sensational stories in regard to Lees Confession, and no matter how improbable the story, it is greedily swallowed.” Others reported from Omaha, “The Lee Case seem[s] to raise the people in bitterness against us as a people which will make the mission harder for [a] while.” [33] James A. Little, who directed missionary efforts in the central United States, complained in April 1877, “This excitement on the Lee affair seems to throw a dark shadow over our former prospects for successful preaching.” He wistfully recalled, “Before the J. D. Lee excitement there was every incentive to labor. Faith and prayer were enlisted in the work. Now faith is down to zero.” [34]

Missionaries in the East reported similar challenges. According to Henry J. Grow in Philadelphia, they were laboring “in the midest of a Set of Blod Hounds that Seak for the Blood of our dear Pres B Young.” Whereas people had formerly listened to the elders, the publication of Lee’s confessions had “changed the minds of the People they turne a deaf Ear to the Truth all the Elders have it to meeat ware Ever they Goe. . . . All Hell is Boiling over.” Grow did his best “to opose the Falst Reports But it is Lik Throing a Ball against the Wall they through it Back in my fase.” [35] Things were largely the same in Michigan, where “many publications” grossly misrepresented “our people, and many put the utmost confidence in this kind of literature, and will believe it without a word of proof, while our testimony is thrown [to] one side, although we substantiate our doctrine with the Scriptures by Chapter and verse.” [36]

A small number of elders were successful despite the groundswell of anti-Mormon feeling. Between May 1876 and July 1877, William M. Palmer, laboring in Michigan, “held 232 meetings & . . . Baptised 36 and expect to Baptise some more.” James A. Little reported in June 1877 that Bengt P. Wulffenstein had baptized twenty persons in Minnesota. Despite his success, however, Wulffenstein acknowledged a recent downturn in the work: “Where i have traveled of late the[y] have not sen a mormon or Latter Day Saint But the[y] know all about President Brigham Young and the Mormons and in particular the Mountain Meaddow.” [37]

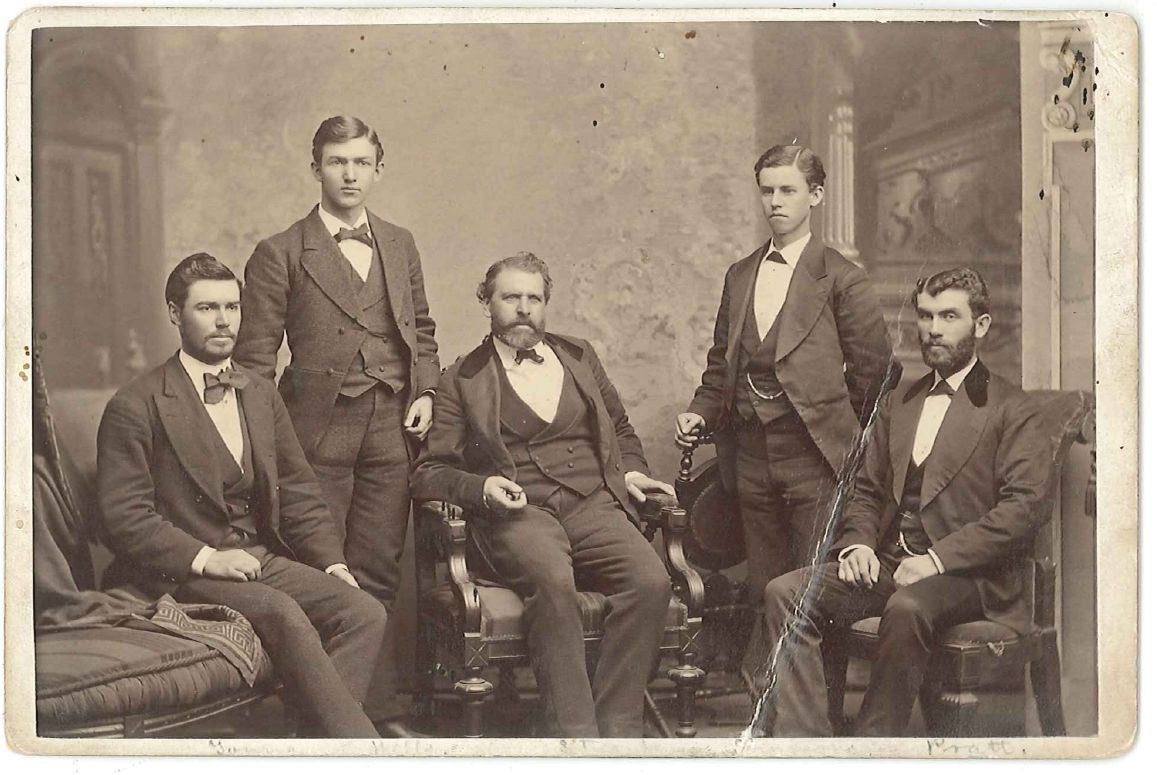

Figure 7. St. Louis Conference missionaries, January 1876, A. J. Fox, photographer. Left to right: Joseph G. Young, Junius F. Wells, David M. Stuart, Joseph M. Simmons, Mathoni W. Pratt.

Figure 7. St. Louis Conference missionaries, January 1876, A. J. Fox, photographer. Left to right: Joseph G. Young, Junius F. Wells, David M. Stuart, Joseph M. Simmons, Mathoni W. Pratt.

David M. Stuart wrote from Canton, Illinois, that the elders laboring with him “were first class men” who had “corrected false testimony, broke down prejudice, <and> convinced the honest in heart that there is a divinity in ‘Mormonism.’ This made the devil mad, and his emissaries howl. they followed in the wake of the Elders with the Lee bible. which swept over the land like a tidal wave. It seemed to me . . . that ten thousand evil spirits bore it with lightning speed to evry point of the compass to divert the minds of the people from the truth.” [38]

Several missionaries became discouraged and returned home. Benjamin F. Cummings Jr. reported from Lowell, Massachusetts, “The papers throughout New England are rife with sensational reports about the ‘Mormons,’” creating a nearly insurmountable barrier for the missionaries. “It seems all but a hopeless task to attempt to stem the flood of falsehood and misrepresentation about our people that has lately been spread over the country.” He noted that three of his associates were returning home to Utah, leaving him and two others as the only Mormon missionaries in Massachusetts and Maine. [39]

James A. Little was caught off guard by the dramatic impact of “the Lee excitement. Such a great change, on such an extensive scale is a new lesson in my experience.” He started releasing missionaries in June 1877. “The work seems gradually closing up in this section.” He reflected, “A time seems to come when both the faith and means of the Elders run out. I have taken this as an indication that it was time to release them to go home.” [40] Church leaders in Salt Lake City also released other missionaries. In May 1877, President Young’s office sent notice “that the brethren laboring in Michigan are at liberty to return home when they wish to do so.” [41]

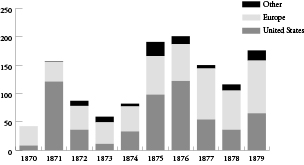

The Church Missionary Record indicates that the number of missionaries called to serve in the United States dropped from 122 in 1876 to 54 in 1877 and to 36 in 1878 (see fig. 9). While fewer missionaries were called to the United States, the number called to Great Britain and Europe increased from sixty-five in 1876 to ninety in 1877. Seventeen elders were called to serve in the northern United States during the first half of 1877, compared with eleven during the second half of the year. [42] It is surprising that any missionaries were called to the northern states after June 1877 in the face of such discouraging results. Brigham Young explained the reason these missionaries were called: “Until the Lord manifests to us by His spirit that the nations of the earth have been sufficiently warned, we shall continue to send forth the Elders to lift up their voices.” [43]

Figure 8. Latter-day Saint missionaries set apart in Salt Lake City, 1870–79. Source: Missionary registers.

Figure 8. Latter-day Saint missionaries set apart in Salt Lake City, 1870–79. Source: Missionary registers.

The initial backlash from the publication of Lee’s confessions was muted in the southern United States. In August, Brigham Young wrote that the South was “at present, the best field for missionary labor.” He attributed it to the humility of the people, they “having suffered so much during the war of the rebellion that their hearts are not hardened to the extent of those who dwell in those sections of the country that did not suffer so greatly from the calamities of those troublesome times.” [44] Young noted elsewhere that in the South, the missionaries “have had considerable success in bringing souls to a knowledge of the truth. A Party of about 140 souls are now on their way, traveling with teams, from Arkansaw with the intention of settling either in New Mexico or with the brethern on the Little Colorado River.” [45] Here was a strange irony: while missionary work was at a standstill in much of the United States, a group of 140 converts was traveling from Arkansas to strengthen Mormon communities in the West. Not only was Arkansas the home state of most of the victims of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, but the size of the 1877 party, 140, was nearly identical to the size of the Fancher party that had been attacked in Utah twenty years earlier. [46]

Invariably, of course, some missionaries in the South also felt repercussions in the late 1870s in the wake of the publicity surrounding John D. Lee’s execution and confessions. John Morgan received a threatening note from members of the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee in about 1877. They claimed to know about the Mormons in Utah. “The fate of your Bishop Lee should be another warning to you. Be it as it may, we will not suffer you any longer to impose upon Some of the ignorant men of this mountain. This is our last warning quit or take the consequence.” [47]

Brigham Young’s Reflections

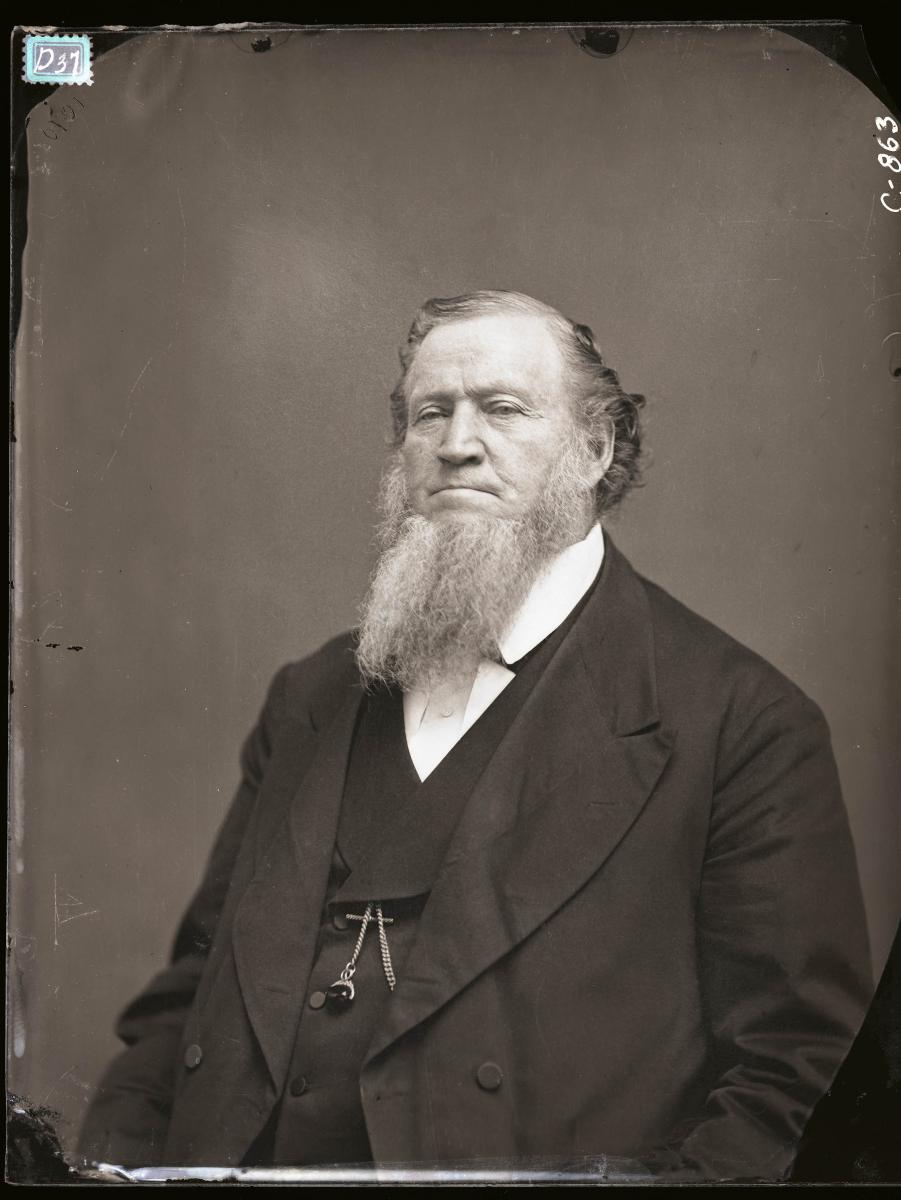

Figure 9. President Brigham Young, ca. 1875, Charles W. Carter, photographer, Charles W. Carter collection.

Figure 9. President Brigham Young, ca. 1875, Charles W. Carter, photographer, Charles W. Carter collection.

Brigham Young (see fig. 10) reflected on the downturn in missionary work in two letters dated July and August 1877. President Young wrote to Apostle Joseph F. Smith on July 27: “There are but few of our Elders now remaining in the States, and probably, under present circumstances, it is well that it is so. . . . The Priests and politicians in the States . . . set about inaugurating a crusade against the Latter day Saints. As usual their weapons were sensations and falsehoods, misrepresentations and abuse. This spirit for a time filled the country, and the people almost universally hardened their hearts, and turned a deaf ear to the words of the Elders. One after another the brethren returned . . . bearing testimony to this feeling: virtually, the people had rejected the Gospel.” [48] Several days later, President Young wrote to the mission president in the Sandwich Islands, saying, “The furor created throughout this country, soon after the execution of Jno. D. Lee, was so great the most of the brethern returned home, feeling satisfied that until that feeling should wear itself out, their labors would be measureably without profit.” [49]

Church Responses

Church leaders did not aggressively seek to counter the bad press that accompanied John D. Lee’s execution and the publication of his so-called confessions. Brigham Young wrote to one of his missionary sons in June: “When you may be assailed, heed it not.” Instead, “proclaim the Truth in meekness, and if they will not listen, leave them to their own folly.” [50] Young gave two interviews to eastern newspapers in May, disavowing any foreknowledge or endorsement of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, but others wanted him to do more. He wrote, “Some of my brethren have felt as though I ought to answer all the falsehoods that have been put in circulation during the last few months against the Latter-day Saints, and which have swept over this nation like a flood.” To such entreaties he responded, “Brethren, I have lived on this earth longer than most of you, and have perhaps a little more experience, when you get to be as old as I am you will learn to trust in God. This is His work, and He will take care of it, if He does not, we cannot.” [51]

Some missionaries attempted, in private and public, to respond to the negative publicity. Elder John Morgan wrote letters to a newspaper in Chattanooga, Tennessee. [52] Elder A. Milton Musser, serving a mission in his native Pennsylvania, wrote pamphlets and obtained newspaper interviews in which he addressed the massacre. He argued that “Brigham Young had no more to do with that tragic affair than the citizens of Philadelphia.” [53] Such efforts did little to sway public opinion. Elder Henry Grow, who labored with Elder Musser for several weeks, described their difficulty in appealing to the press: “We have tryed to Get Somting Publish in the Papers But our Cause is Just But they Cant do any thing for us.” One editor told the elders that while he thought the Mormons were “very fine People,” he did not “Publish aney thing in favour of Mormon<ism>.” According to Grow, “The Christan Controle the Editors and the Devel them all. . . . If they Can Get a Lie from Utah to Publish it makes ther Paper Sell Good.” [54]

Conclusion

Brigham Young passed away on August 29, 1877. The furor over the Mountain Meadows Massacre gradually subsided but never completely died. In the 1880s, playing the steady drumbeat of polygamy and Mountain Meadows, anti-Mormon books, articles, and lectures, augmented by dramatic presentations, continued to popularize the notion that Mormon men were licentious, Mormon women were victimized, and Mormon culture was violent. [55] The South, whose people Brigham Young had characterized as being less hardened than their northern neighbors, became a rather hazardous proselytizing field, evidenced by the murders of missionaries in Georgia and Tennessee in 1879 and 1884. Two local Church members were also killed in the Tennessee incident. [56]

Beginning in 1881, the Church made greater efforts to refute charges that Brigham Young was responsible for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. In an 1884 address, Mormon apologist Charles W. Penrose acknowledged the troubles that the massacre had caused for the Church. “Wherever our Elders have gone abroad to preach the gospel of Christ, . . . the cry of ‘The Mountain Meadows Massacre’ [is] raised against them. It is claimed that that awful tragedy was . . . perpetrated at the command of Brigham Young as the leader of the Church, and that it was in accordance with the doctrines of the Church. This untruth has been repeated so many times that the world . . . have come to believe in a great measure that it is true.” [57]

J. Golden Kimball visited Mountain Meadows in 1897. He described the scene in his journal: “We . . . went . . . to a monument of rock which marked the spot where John D. Lee was shot; by the officers of the law, for the terrible crime of the Mountain Meadow Massacre. I stood on the ground where 130 persons were killed. It was with peculiar, and solemn feelings when I comprehended the enormity of the crime and the injury done the Church of Christ. The persecution Elders had passed through, and that I had during five years missionary experience in the Southern States.” [58] Kimball echoed the sentiments of Utah’s congressional delegate, John M. Bernhisel, who wrote to Brigham Young in 1862: “This atrocious affair has done us and still continues to do us as a people, incalculable injury, . . . and the miscreants who were engaged in this cold blooded and diabolical deed, will have a fearful account to render in the judgment of the great day.” [59]

Notes

[1] J. Golden Kimball, in Conference Report, April 1932, 78–79; Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941), 822.

[2] Second District Court (Utah), grand jury indictment, September 1874, criminal case file 31, series 24291, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City; Second District Court (Utah), arrest warrant for John D. Lee, October 13, 1874, Minute Book B, 289–90, Leavitt Special Collections, Sherratt Library, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, Utah; “The Lee Trial,” Salt Lake Herald, August 8, 1875.

[3] W. C. Staines to Brigham Young, July 27, 1875, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[4] William C. Staines to Brigham Young, August 20, 1875, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library; “Needful,” Pioche Daily Record, August 8, 1875.

[5] George Q. Cannon to Brigham Young, January 3, 1876, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[6] The New York Times carried four massacre-related articles in September 1876, the month of Lee’s conviction, and five in March 1877, when he was executed and some of his confessions were published. ProQuest Historical Newspapers has copied the New York Times, 1851–2007, as PDF files. The total size of the September 1876 articles on the massacre is 148 KB, while the relevant March 1877 articles total 882 KB, a nearly six-fold increase.

[7] Sanford Bingham to Orson Pratt, June 23, 1877, Missionary Reports, 1831–1900, Church History Library. Original capitalization and orthography have been retained in documents quoted in this paper.

[8] J. H. Beadle, Life in Utah; Or, the Mysteries and Crimes of Mormonism (Philadelphia: National Publishing, 1870), 186–87; publisher’s prospectus for J. H. Beadle, The Undeveloped West; Or, Five Years in the Territories: Being a Complete History of That Vast Region between the Mississippi and the Pacific, Its Resources, Climate, Inhabitants, Natural Curiosities, Etc., Etc. (Philadelphia: National Publishing, 1873), copy in Church History Library.

[9] A Mormon Chronicle: The Diaries of John D. Lee, 1848–1876, ed. Robert Glass Cleland and Juanita Brooks (1955; reprint, San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 2003), 2:203, 210–11; Beadle, Undeveloped West, 646–53.

[10] Ronald W. Walker, “The Stenhouses and the Making of a Mormon Image,” in Mormon Mavericks: Essays on Dissenters, ed. John Sillito and Susan Staker (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 101.

[11] Fanny Stenhouse, Exposé of Polygamy in Utah: A Lady’s Life Among the Mormons (New York: American News, 1872).

[12] Fanny Stenhouse, “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism (Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington, 1874), 324–38; see esp. 325–26, 328, and 337.

[13] Fanny Stenhouse, “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism, 2nd ed. (Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington, 1878), 626–55.

[14] T. B. H. Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints: A Full and Complete History of the Mormons, from the First Vision of Joseph Smith to the Last Courtship of Brigham Young (New York: D. Appleton, 1873), 357, 424–59. Other authors quoted by Stenhouse include John Cradlebaugh, Jacob Forney, J. H. Beadle, and Catharine V. Waite.

[15] Stenhouse, Rocky Mountain Saints, 357, 431.

[16] Walker, “The Stenhouses and the Making of a Mormon Image,” 117, 122.

[17] George Q. Cannon to Brigham Young, February 27, 1873, Brigham Young office files, CR 1234 1, Church History Library.

[18] George Q. Cannon to Brigham Young, May 16, 1872, and February 20, 1873, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library; Job Welling, diary, February 17, 1876, Church History Library.

[19] Samuel J. Wing to Brigham Young, January 17, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[20] Mark Twain, Roughing It (Hartford, CT: American Publishing, 1872), 576–79; John Cradlebaugh, Utah and the Mormons: Speech of Hon. John Cradlebaugh, of Nevada, on the Admission of Utah as a State (Washington, DC: L. Towers, 1863); Catharine V. Waite, The Mormon Prophet and His Harem (Cambridge, MA: Riverside, 1866), 60–77. Waite’s was the first anti-Mormon book to devote a section to the massacre. Catharine lived in Utah while her husband, Charles, served as a federally appointed judge from 1862 to 1864. She claimed that Brigham Young received a revelation commanding southern Utah leaders to “follow those cursed gentiles . . . attack them, disguised as Indians, and with the arrows of the Almighty make a clean sweep of them, and leave none to tell the tale” (66). See also Jody Scott, “Catharine Van Valkenburg Waite,” paper for Women’s Legal History Project, Stanford Law School, n.p., n.d., 10, 20.

[21] Ann Eliza Webb Young, Wife No. 19, or the Story of a Life in Bondage, Being a Complete Exposé of Mormonism, and Revealing the Sorrows, Sacrifices, and Sufferings of Women in Polygamy (Hartford, CT: Dustin, Gilman, 1875); see esp. pp. 228–61; George Q. Cannon to Brigham Young, April 18, 1874, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library; Matthew J. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden”: Thomas L. Kane, Romantic Reformer (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 267–68; C. F. McGlashan, “The Mountain Meadow Massacre,” Sacramento Daily Record, January 1, 1875.

[22] Young, Wife No. 19, 233, 248.

[23] Job Smith to Brigham Young, February 3, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library; “Lee’s Last Confession,” San Francisco Daily Bulletin Supplement, March 24, 1877.

[24] Brigham Young to Isaac C. Haight, September 10, 1857, letterbook, 3:827–28, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[25] Mormonism Unveiled: Or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee, ed. William W. Bishop (St. Louis: Bryan, Brand, 1877), 34; William W. Bishop to William Nelson, December 20, 1876, and William W. Bishop to John D. Lee, March 9, 1877, John D. Lee Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

[26] “Lee’s Confession,” New York Herald, March 22, 1877; “John D. Lee Makes a Confession of His Crimes,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 1877. A condensed version of the statement also appeared in the San Francisco Daily Evening Post on March 22.

[27] James Gordon Bennett to Brigham Young, telegram, March 21, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[28] Brigham Young to James Gordon Bennett, March 22, 1877, in “Lee’s Confessions,” Deseret News, March 28, 1877.

[29] William W. Bishop version: “Lee’s Confession,” New York Herald, March 22, 1877; “John D. Lee Makes a Confession of His Crimes,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 1877; “Mountain Meadows. John D. Lee’s Confession,” San Francisco Daily Evening Post, March 22, 1877; “Mountain Meadows. The Confession of Lee the Great Mormon Criminal,” Daily Gazette and Bulletin (Williamsport, Pennsylvania), March 23, 1877; “Execution of Lee!,” Pioche Weekly Record, March 24, 1877; “Mountain Meadows Massacre. John D. Lee’s Confession,” Los Angeles Weekly Express, March 24, 1877; “Reported Confession of John D. Lee,” Ogden Junction, March 26, 1877.

Sumner Howard version: “Lee’s Last Confession,” San Francisco Daily Bulletin Supplement, March 24, 1877; “Lee’s Confession,” Sacramento Daily Record-Union, March 24, 1877; “Lee’s Confession,” San Francisco Daily Morning Call, March 24, 1877; “Lee’s Confession,” Daily Alta California, March 24, 1877; “Confession of Lee,” New York Times, March 24, 1877; “Another Confession,” New York Herald, March 24, 1877; “John D. Lee Shot in Utah,” New York Daily Tribune, March 24, 1877; “The Confession of Lee,” Omaha Republican, March 24, 1877; “John D. Lee!,” Daily Quincy Herald, March 24, 1877; “The Confession!” Salt Lake Tribune, March 28, 1877.

[30] Mormonism Unveiled, vii. The confession is on pages 213–59. Chad J. Flake and Larry W. Draper, A Mormon Bibliography, 1830–1930, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004), 1:628–29.

[31] Leonard John Nuttall, diary, March 31, 1877, Church History Library.

[32] John H. Krenkel, ed., The Life and Times of Joseph Fish, Mormon Pioneer (Danville, IL: Interstate, 1970), 168.

[33] Philip Hurst, diary, March 1877, Church History Library; F. F. Hintze and A. Frantzen to Brigham Young, April 3, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[34] James A. Little to George Reynolds, April 16, 1877, and James A. Little to Brigham Young, April 28, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[35] Henry Grow to George Reynolds, April 19, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[36] Orson H. Eggleston to Brigham Young, May 2, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[37] William M. Palmer to Brigham Young, July 18, 1877; James A. Little to Brigham Young, June 16, 1877; and B. P. Wulffenstein to Brigham Young, July 10, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[38] David M. Stuart to Brigham Young, May 31, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library. The document includes penciled alterations, apparently by someone other than the author; the changes have been ignored.

[39] B. F. Cummings to Brigham Young, May 12, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[40] James A. Little to Brigham Young, June 2, 13, and 16, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.

[41] George Reynolds to Orson H. Eggleston, May 24, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 14:849, Church History Library; Orson H. Eggleston, diary, May 29, 1877, Church History Library.

[42] Missionary Department, missionary registers, 1860–1959, vol. 1, 17–48, Church History Library. Of the eleven missionaries called between June and December 1877, six were called simply to the “U.S.” Of the remaining five, three were called to Wisconsin, one to Pennsylvania, and one to Ohio. The mission designation for a twelfth missionary called during this period was “U.S., Canada, Scot[land].” Designations for missionaries called to the South during the same period were either “Southern States” or, in one instance, “Kentucky.”

[43] Brigham Young to David M. Stuart, June 13, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 14:927, Church History Library.

[44] Brigham Young to John Morgan, August 7, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 15:125, Church History Library.

[45] Brigham Young to W. E. Pack, August 6, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 15:119, Church History Library.

[46] Jacob Forney to A. B. Greenwood, August 1859, in Message of the President of the United States, Communicating, in Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate, Information in Relation to the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, and Other Massacres in Utah Territory, S. Doc. No. 36-42, at 75 (1860).

[47] KKK to John Morgan, undated, reproduced in Arthur M. Richardson and Nicholas G. Morgan Sr., The Life and Ministry of John Morgan (Salt Lake City: Nicholas G. Morgan Sr., 1965), 134.

[48] Brigham Young to Joseph F. Smith, July 27, 1877, in “Foreign Correspondence,” Millennial Star, September 3, 1877, 570.

[49] Brigham Young to W. E. Pack, August 6, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 15:118–19, Church History Library. Note that “Jno.” was a common abbreviation for John at the time.

[50] Brigham Young to Lorenzo D. Young, June 15, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 14:931, Church History Library.

[51] Jerome B. Stillson, “Brigham Young. Remarkable Interview with the Salt Lake Prophet,” New York Herald, May 6, 1877; Eli Perkins, “Brigham Young. A Long Talk with the Prophet,” New York Times, May 20, 1877; Brigham Young to Lorenzo D. Young, June 15, 1877, letterbook, Brigham Young office files, 14:931–32, Church History Library.

[52] Facts on the Mormon Question: One of a Series of Letters Published in the Chattanooga Daily Commercial, by Elder Jno. Morgan, in reply to G. C. C. (n.p., 1878?). The broadside contains no references to the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

[53] A. Milton Musser, To the Press of the United States, May 1877 (n.p.: Philadelphia, 1877); “The Mormons: A Tale of Their Missionaries,” Philadelphia Weekly Times, May 26, 1877; A. Milton Musser and Orson F. Whitney, Please Read This Free Circular on “Mormonism,” Then Hand It to Your Neighbor (n.p.: Philadelphia, 1877?); A. M. Musser, Malicious Slanders Refuted!!! (Liverpool: Millennial Star, 1877?); A. Milton Musser, The Fruits of Mormonism (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1878).

[54] Henry Grow to Brigham Young, May 17, 1877, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library. The missionaries had an article printed in the Philadelphia Weekly Times a short time later (see previous note).

[55] See, for instance, Fanny W. Stenhouse, An Englishwoman in Utah: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1880), 380–97; Mrs. A. G. Paddock, The Fate of Madame La Tour: A Tale of Great Salt Lake (New York: Fords, Howard, and Hulbert, 1881), 300–305; J. M. Coyner, Hand-Book on Mormonism (Salt Lake City: Hand-Book Publishing, 1882), 67–72; The Crimes of the Latter Day Saints in Utah (San Francisco: A. J. Leary, 1884), 48–52; Frank Triplett, History, Romance and Philosophy of Great American Crimes and Criminals: Including the Great Typical Crimes That Have Marked Various Periods of American History from the Foundation of the Republic to the Present Day (New York and St. Louis: N. D. Thompson, 1885), 196–209; G. A. Custer, Wild Life on the Plains and Horrors of Indian Warfare (St. Louis: Sun, 1886), 498–528; J. P. Dunn Jr., Massacres of the Mountains: A History of the Indian Wars of the Far West (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1886), 273–323; C. P. Lyford, The Mormon Problem, An Appeal to the American People (New York: Phillips and Hunt, 1886), 271–323. Dramatic portrayals of the massacre were included in Sam W. Smith, California through Death Valley: A Drama in Four Acts, adapted for dramatic representation by John Woodward (San Francisco: Valentine, 1880?); Joaquin Miller, ’49: The Gold-Seeker of the Sierras (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1884).

[56] Patrick Q. Mason, The Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormonism in the Postbellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 21–56.

[57] George Q. Cannon, “Utah and Its People,” North American Review, no. 294 (May 1881): 459–60; Charles W. Penrose, The Mountain Meadows Massacre. Who Were Guilty of the Crime? . . . An Address . . . October 26, 1884 (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1884), 5–6.

[58] J. Golden Kimball, Journal, September 16, 1897, Church History Library. Kimball erroneously stated that the monument “marked the spot where John D. Lee was shot.” According to the Salt Lake Tribune, Lee was executed “on the ground where the emigrants camped, a few rods from the monument.” “The Last of Lee,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 24, 1877. See also Morris A. Shirts and Frances Anne Smeath, Historical Topography: A New Look at Old Sites on Mountain Meadows (Cedar City, UT: Southern Utah University Press, 2002), 67–68.

[59] John M. Bernhisel to Brigham Young, July 11, 1862, Brigham Young office files, Church History Library.