Defending Mormonism

The Scandanavian Mission Presidency of Andrew Jenson, 1909–12

Alexander L. Baugh

Alexander L. Baugh, "Defending Mormonism: The Scandinavian Mission Presidency of Andrew Jenson, 1909–12," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 503–41.

Alexander L. Baugh was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this book was published.

On December 9, 1908, Assistant Church Historian Andrew Jenson received a letter from Joseph F. Smith, John R. Winder, and Anthon H. Lund, the Church’s First Presidency, notifying him of his appointment to preside over the Scandinavian Mission, headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark, where he would replace Søren Rasmussen, who had been serving as president since November 1907. It is not known if Jenson anticipated receiving the call, but he accepted the call in spite of the many responsibilities associated with his work in the Historian’s Office. It was expected that he would leave as soon as he could get his affairs in order. The next five weeks were busy ones for the newly called mission president, both at the Historian’s Office and at home. In addition, he set aside time to visit family members and acquaintances and enjoyed farewell dinners and social get-togethers hosted by well-wishers.

President Joseph F. Smith formally set apart Andrew Jenson on January 12, 1909. Five days later, Jenson delivered a farewell address to a large congregation in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. The following day, January 18, at the Salt Lake train depot, he said his last good-byes to his two wives, Emma and Bertha (the two women were sisters), his immediate family, his colleagues, and Church officials, and he boarded an eastbound train. At the time he was not entirely sure how long his mission would last or when he would return. [1]

En route to New York City, Jenson made stops in Kansas City, Chicago, Cleveland, and Rochester, visiting Church historic sites along the way. In New York, he boarded the ship Baltic on January 30 for a nine-day journey to Liverpool. From Liverpool he traveled to London, where he went by steamer to Amsterdam, then traveled by rail the rest of the way to Copenhagen, where he arrived on February 11, taking over the leadership of the mission four days later. [2]

Jenson’s call to preside over the Scandinavian Mission came at a time of widespread anti-Mormon agitation, in both the United States and Europe but more particularly in Great Britain and Denmark. However, he was well suited to the task and was an able defender of the faith.

Early Life, Missions, and Career

Fifty-eight-year-old Andrew Jenson was well prepared to serve as president of the Scandinavian Mission. Andrew was born on December 11, 1850, in Torslev, Hjørring, Denmark, and his parents, Christian and Kristen Jenson, were early converts in northern Jutland, joining the Church when Andrew was only four years old. The family immigrated to America when Andrew was fifteen, eventually settling in Pleasant Grove, Utah. In 1873, Andrew, then twenty-three, received a mission call to return to his homeland. He labored principally in Aalborg and while there wrote a short history of the Aalborg Conference. That exercise marked the beginning of what would be his life’s mission—writing Mormon history. In 1876, one year after returning from his first mission, aided by Erastus Snow and Johan A. Bruun, Jenson published a history of the Prophet Joseph Smith in Danish. The work was titled Joseph Smith’s Levnetsløb (The Life of Joseph Smith). Two years later, he began assisting in the translation of several articles for Bikuben (The Beehive), a Danish publication started by A. W. Winberg in 1876.

In 1879, Andrew Jenson received his second mission call to Denmark. While serving on this mission, he was appointed assistant to the mission president, during which time he edited a monthly periodical for the young people of the mission titled Ungdommens Raadgiver (Counselor of Youth). Still later, he became the assistant editor of the mission periodical Skandinaviens Stjerne (Star of Scandinavia). The highlight of this mission, however, was the responsibility he received to translate a new edition of the Book of Mormon, published in 1880. Returning to Utah in 1881, Andrew Jenson received permission from Erastus Snow of the Quorum of the Twelve to begin a new Danish publication titled Morgenstjernen (Morning Star), a monthly periodical that was published until 1886. Significantly, while editing and publishing Morgenstjernen, Jenson also translated and published the Pearl of Great Price into Danish for the first time.

In 1886, Church leaders desired that Morgenstjernen become an English-language periodical and be made available to the entire Church. Jenson named the new English publication The Historical Record, a monthly periodical devoted to historical, bibliographical, chronological, and statistical matters associated with the Church. That same year, Jenson also published Church Chronology, a companion volume to the Historical Record, containing a compilation of major events that took place in the Church between 1830 and 1884. His work on these publications led to him receiving a stipend to work in the Historian’s Office although he was not an official employee.

From 1888 to 1898, Andrew Jenson was perhaps the most widely traveled individual in the Church. In 1888, he, along with Edward Stevenson and Joseph Smith Black, went on a historical fact-finding mission to Missouri, Illinois, New York, Ohio, and Iowa. Between 1892 and 1894, he visited all of the Latter-day Saint communities and stakes in Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, California, Arizona, Mexico, and Canada to collect historical information. Then, in 1895, he commenced his most extensive undertaking—the responsibility to travel around the world visiting all the international missions and collecting their records. This two-year mission took him to many islands of the South Pacific, Australia, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, England, Wales, Ireland, Scotland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. His diligent labors and activities led to his official appointment on October 19, 1897, as Assistant Church Historian, for which he is most well known.

As Assistant Church Historian, Andrew Jenson assisted Mormon Apostle and Church Historian Anthon H. Lund in compiling the Journal History of the Church, a day-by-day manuscript narrative of the history of the Church. [3] In 1901, Jenson published a second edition of Church Chronology, followed in 1904 with what would be the first of four volumes of the Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia. [4]

Jenson served yet another mission, his third, to Denmark in 1902–3. During this mission, he oversaw the publication of a new Danish edition of the Book of Mormon (the fourth edition), which project he and Anthon H. Lund worked on together. In 1904, he returned to Denmark once again, this time to oversee and publish a new edition of Joseph Smith’s Levnetsløb. Thus, at the time of his appointment in 1909 as president of the Scandinavian Mission, he was well qualified for the task. He was a native Dane and was well versed in Danish. He understood the Scandinavian culture and people. He was one of the most widely traveled men in the Church. Finally, he was informed, well read, and literarily proficient, having translated or written more books and materials than any other Mormon leader or Latter-day Saint then living. [5]

The Scandinavian Mission

At the time Andrew Jenson began his mission presidency, the Scandinavian Mission comprised the countries of Denmark and Norway, although Iceland also came under the mission’s jurisdiction. Between 1850 and 1905, the Scandinavian Mission consisted of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, but in 1905, Sweden became a separate mission. Denmark and Norway continued as the Scandinavian Mission until 1920, at which time they were separated into two missions. [6] The mission consisted of six conferences—three in Denmark and three in Norway—comprising thirty-nine branches (see table 1 and fig. 1). At the time of Jenson’s arrival, the missionary force numbered 138. [7] Generally, between fifteen and twenty-five full-time missionaries were assigned to each conference.

Table 1. Scandinavian Mission Conferences, 1909

| Denmark Conferences | Branches |

| Copenhagen | 7 |

| Aarhus | 6 |

| Aalborg | 5 |

| Norway Conferences | |

| Christiania (Oslo) | 11 |

| Bergen | 5 |

| Trondheim | 5 |

| Total | 39 |

A statistical analysis of the missionaries assigned to the Scandinavian Mission in the three-year period from 1909 through 1911 reveals some interesting facts. [8] Of the 173 missionaries assigned to the mission during this three-year period, 141 (82 percent) came from Utah, twenty-three (13 percent) came from Idaho, with the remaining nine (5 percent) coming from Canada (5), Nevada (2), Colorado (1), and Wyoming (1). Thirty missionaries were from Salt Lake County (17 percent), but Sanpete County (sometimes referred to as Utah’s “little Scandinavia”) was not far behind with twenty-four (14 percent). Adding Emery and Sevier counties to the Sanpete number, a total of forty-four missionaries, or roughly one-fourth (25 percent) of the missionaries, came from central Utah. The counties with the next highest number of missionaries called to the Scandinavian Mission were Cache and Utah with seventeen missionaries each (both 10 percent). Thirteen missionaries came from Box Elder (8 percent). [9] Jenson’s published writings and histories of the mission indicate that the entire missionary force was made up exclusively of missionaries from the United States—no full-time missionaries were called from the general membership of the Church living in Denmark or Norway, although local members assisted in proselytizing activities.

Figure 1. Map showing the six conference headquarters in the Scandinavian Mission, 1909–12. Map courtesy of Mark W. Jackson, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Figure 1. Map showing the six conference headquarters in the Scandinavian Mission, 1909–12. Map courtesy of Mark W. Jackson, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Significantly, a large number of missionaries called to the Scandinavian Mission were young men of Scandinavian descent, many being sons or grandsons of native Danish and Norwegian parents or grandparents. For missionaries who had been raised in homes of native Scandinavians, many, like Elder Aaron P. Christiansen of Mayfield, Utah, had already acquired some degree of understanding and competency in Danish as a second language. His parents, Parley Christiansen and Dorthea Kirstine Jensen Scow, emigrated from Denmark to Utah in the 1850s and 1860s and spoke both Danish and English in their home. When Aaron arrived in Denmark, he already understood and spoke the language, greatly facilitating his transition to missionary work. [10]

The large number of the missionaries called from Mormon families with Scandinavian backgrounds is also reflected in the surnames of the missionaries. For example, between 1909 and 1911, twenty-two missionaries in the mission had the last name of Jensen/

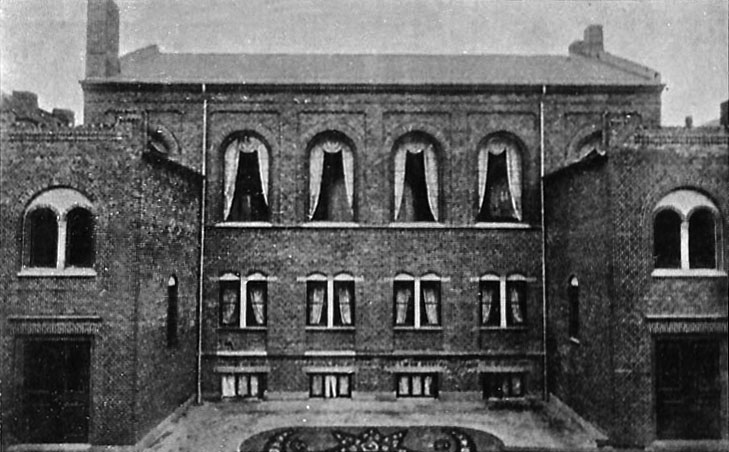

The Church owned four buildings in the mission—three in Denmark and one in Norway—and all four served as meetinghouses. The largest of these was the mission headquarters in Copenhagen, completed and dedicated in July 1902, and located at Korsgade #11, Copenhagen. The building was an impressive three-story structure. The basement floor included a kitchen, two pantries, a dining room, baptistery, dressing rooms, and a furnace room. The second, or main, floor included a small assembly room, office rooms, and four bedrooms, one of which President Jenson occupied. The upper story comprised the main assembly hall (75 x 40 x 24 feet), complete with a gallery, and could accommodate upwards of seven hundred people. Two side buildings attached to the main structure served as entryways to the building (see fig. 2). [12]

Figure 2. Scandinavian Mission headquarters and meetinghouse, Korsgade #11, Copenhagen, Denmark, photographer unknown.

Figure 2. Scandinavian Mission headquarters and meetinghouse, Korsgade #11, Copenhagen, Denmark, photographer unknown.

Church members in Aarhus met in a three-story building located at Borupsgade #14, built by the local Saints in 1876. Like the Copenhagen building, the upper floor served as an assembly hall and had a seating capacity for three hundred persons. [13] In July 1907, eighteen months before Jenson took over as mission president, the Church completed the construction of a two-story red brick chapel and conference house located in Aalborg, where the upper floor also served as a meeting hall for some three hundred people (see fig. 3). [14] The only Church-owned building in Norway was in Christiania (Oslo), completed in July 1903. [15] Each of these buildings contained elements similar to the Copenhagen building (a kitchen, baptistry, changing rooms, and office rooms). Since the Saints in Bergen and Trondhjem did not have their own buildings, they rented halls for their conferences and church meetings. In April 1912, however, as he was completing his presidency, Jenson purchased a spacious two-story rock building as a meetinghouse for the Saints in Bergen. [16]

Figure 3. The original Aalborg LDS meetinghouse, Valdemarsgade #2, Aalborg, Denmark, June 2000. The building was completed in 1907 and sold by the LDS Church several years ago. The building is currently used as an apartment house. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Figure 3. The original Aalborg LDS meetinghouse, Valdemarsgade #2, Aalborg, Denmark, June 2000. The building was completed in 1907 and sold by the LDS Church several years ago. The building is currently used as an apartment house. Photograph by Alexander L. Baugh.

Jenson was assisted in his presidency by Oluf J. Andersen, editor of the Skandinaviens Stjerne, and a mission secretary (see fig. 4). These three men essentially constituted the officers of the mission, although each conference also had a conference president and secretary who were also full-time proselytizing elders.

Figure 4. Andrew Jenson (left) and Oluf J. Anderson (right), in front of the Scandinavian Mission headquarters, Korsgade #11, Copenhagen, Denamark, ca. 1909–12. The women in the photograph are not identified. Anderson served as editor of the Skandinaviens Stjerne, the mission periodical. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection in the possession of Alexander L. Baugh.

Figure 4. Andrew Jenson (left) and Oluf J. Anderson (right), in front of the Scandinavian Mission headquarters, Korsgade #11, Copenhagen, Denamark, ca. 1909–12. The women in the photograph are not identified. Anderson served as editor of the Skandinaviens Stjerne, the mission periodical. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection in the possession of Alexander L. Baugh.

Mission Conference Tours

President Jenson conducted a tour of the six mission conferences each spring and fall for a total of seven times during the thirty-three months of his presidency. The spring tour would usually begin around the end of March and continue for the next five or six weeks, ending sometime in May. The fall tour would be begin the latter part of September and continue until the first or second week of November. Generally the first conference was held in Copenhagen, then in Aarhus, followed by Aalborg, Christiania (Oslo), Bergen, and ending in Trondhjem. Jenson also visited with the Saints and missionaries at various times throughout the year, but the semiannual spring and fall meetings were the official conferences, attended by both members and missionaries. The main conference meetings were scheduled for Saturday and Sunday, but additional meetings were scheduled to be held during the first part of the week (Monday through Wednesday). Attendees would arrive at the conference headquarters on Saturday, with the first session being held that evening. In this meeting, the full-time presiding elders gave reports respecting their specific branch assignments. Three conference sessions took place on Sunday—a Sunday School conference in the morning, a general session in the afternoon, and another general session in the evening. President Jenson was generally the main speaker during these sessions, and he preached on a variety of gospel subjects. His depth of gospel knowledge is reflected in the topics on which he spoke, including the plan of salvation, the organization of the Church, the man-made system of religion in the world, the necessity of continuing revelation, the influence LDS doctrine has had on the Protestant churches, the Articles of Faith, the fruits of Mormonism and growth of the Church, the personality of God, the requirements of those who are candidates for salvation, the divine authenticity of the Book of Mormon, answers to false reports regarding the Mormons, the American Indians and the Book of Mormon, the Millennium and Resurrection, and “What Is True Christianity?” Newspaper reports indicate that President Jenson was a gifted and dynamic speaker who could hold the attention of his audience, member and nonmember alike. Most of the time he spoke in his native Danish, but he occasionally gave talks in English (probably when he was speaking exclusively to the full-time American missionaries).

In the Sunday afternoon and evening sessions, the full-time elders were given the opportunity to bear their testimonies, the general and local officers were sustained, statistical reports were read, and remarks were given by mission leaders. As a self-trained historian, Jenson recognized the importance of keeping accurate records. During the conferences he was also known to take the time to examine the conference records and reports and made sure that they were being kept properly.

Monday morning the elders met in a special priesthood meeting with President Jenson, where they gave reports and shared experiences concerning their missionary activities, followed by instruction from the president. That evening, a sacrament meeting was held, with instruction again being given by President Jenson and other mission or conference officers. Conference sessions for the Relief Society (and sometimes the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association and Young Ladies’ Mutual Improvement Association) were held on Tuesday evenings.

Wednesday evening a general meeting was held. It was during this meeting that President Jenson discussed more secular topics or talked about the trip he took around the world in 1895–97. In Copenhagen, the conference sometimes lasted through Friday night. However, in the other localities, the conference concluded on Thursday with members and missionaries enjoying an evening gala of food and entertainment. These conferences also showcased the conference choir, the pride and joy of the local branches. Oftentimes, the missionaries posed with President Jenson for a photograph (see figs. 5 and 6). Then it was on to the next conference, which was scheduled for the next city beginning Saturday evening. These conferences were well attended by upwards of four hundred to six hundred people, including sometimes as many as one hundred nonmembers. For the Saints, conference week was a wonderful time to enjoy fellowship with one another and renew acquaintances.

During conference week, time was frequently allotted for sightseeing. Saturdays and Sundays were taken up in meetings, but since the meetings attended by local Church members on weekdays were generally held in the evenings, time was left during the day to do some sightseeing, something Jenson did everywhere he went. He loved visiting places.

Figure 5. Andrew Jenson (second row, center) and the missionaries serving in the Copenhagen Conference, March 28, 1911. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection. Elder Aaron P. Christiansen, the author's grandfather, is pictured on the back row, fourth from the left, the tallest missionary in the group.

Figure 5. Andrew Jenson (second row, center) and the missionaries serving in the Copenhagen Conference, March 28, 1911. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection. Elder Aaron P. Christiansen, the author's grandfather, is pictured on the back row, fourth from the left, the tallest missionary in the group.

Figure 6. Andrew Jenson (center, with the bow tie) with Danish Latter-day Saint members and missionaries, ca. 1911 or 1912. The photograph was probably taken at an outing during one of President Jenson's conferences in Copenhagen. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection.

Figure 6. Andrew Jenson (center, with the bow tie) with Danish Latter-day Saint members and missionaries, ca. 1911 or 1912. The photograph was probably taken at an outing during one of President Jenson's conferences in Copenhagen. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection.

A report of the conference was written up by the conference secretary, who submitted the record to the mission office. President Jenson regularly forwarded the conference reports (or one of his own) to Salt Lake City, where they were picked up by the Deseret Evening News, thus allowing parents and family members of the missionaries, and native Danes and Norwegians living in Utah, to read and learn about what was happening in the mission and in the conferences. Probably at the encouragement of President Jenson, mission and conference secretaries regularly sent feature reports and news articles to Salt Lake City and Liverpool, England (European Mission headquarters, where the Millennial Star was published). During his three-year stint, over one hundred articles and photographs highlighting the activities of the Scandinavian Mission appeared in the Deseret Evening News, Improvement Era, and Millennial Star. [17] Reports of the conferences also appeared in the mission periodical Skandinaviens Stjerne.

Missionary Proselytizing Activity

Missionary work and proselytizing activity in the early 1900s differed considerably from that which is done today. No standard discussions existed, so missionaries taught the restored gospel informally in simple religious discussions and conversations, sometimes using the Articles of Faith as a springboard. A major converting factor was getting individuals to read Church- and mission-produced literature—particularly the Book of Mormon and the Pearl of Great Price, and gospel tracts such as Charles W. Penrose’s Rays of Living Light—and the Skandinaviens Stjerne. Investigators were also encouraged to attend the congregational activities and Mormon worship services.

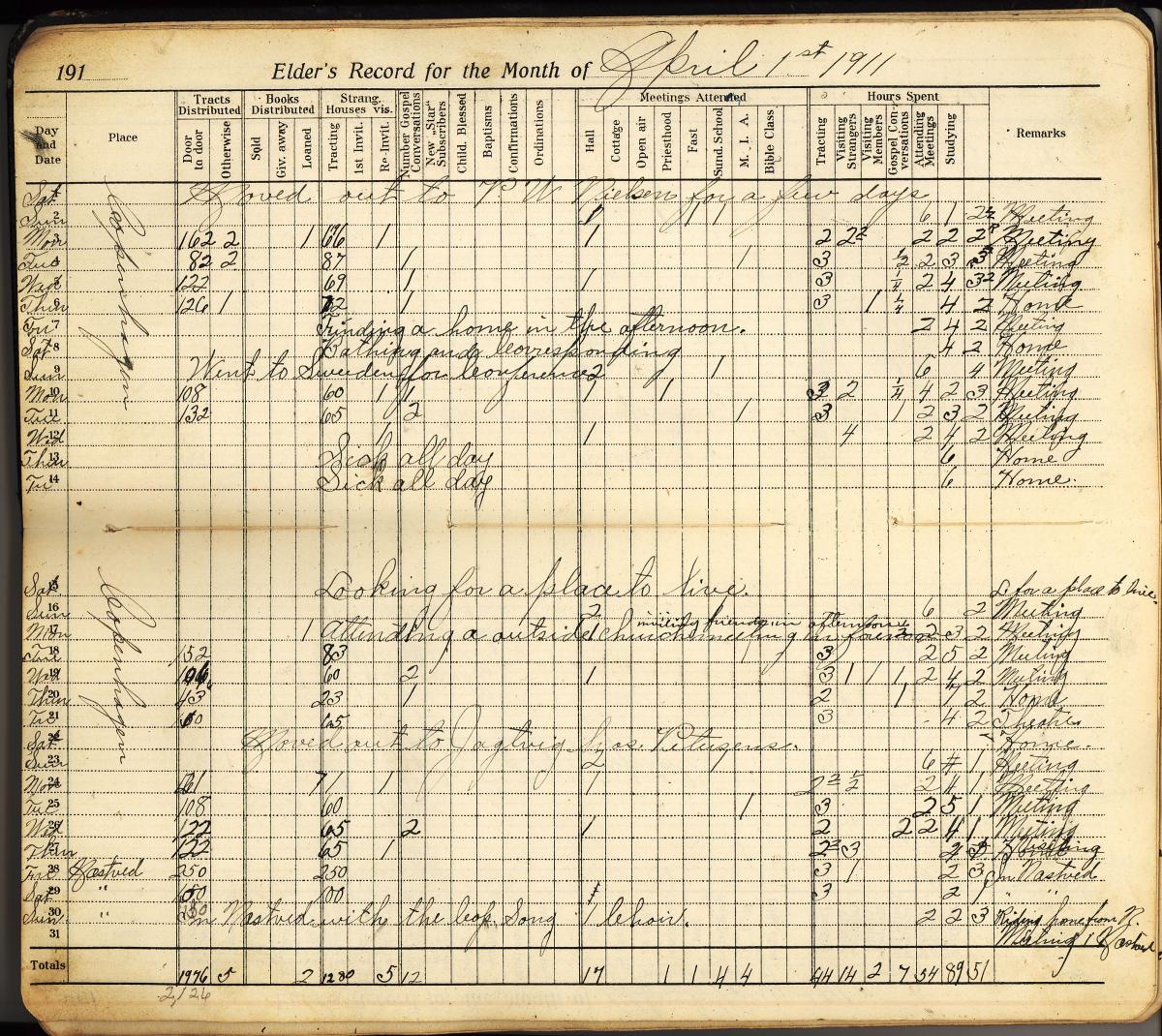

All missionaries received a mission log or record book to write down their daily missionary work and proselytizing activity. For example, each elder was expected to record (1) the number of missionary tracts distributed; (2) the number of copies of the Book of Mormon loaned or given away; (3) the number of “strangers’” (non-Mormon homes) visited; (4) the number of gospel conversations; (5) and new subscriptions to the Skandinaviens Stjerne. In addition, they were to record the meetings attended (under the categories of Hall, Cottage, Open Air, Priesthood, Fast Meeting, Sunday School, MIA, and Bible class).They were also to record the time spent tracting, visiting strangers (non-Mormons), visiting members, attending meetings, studying, and having gospel conversations. Other categories included the number of children blessed and the number of people baptized, confirmed, or ordained to the priesthood. The missionaries reported these numbers and figures to the conference president and secretary, who used them to compile statistical reports of the conference and the entire mission.

Examining the record book of Elder Aaron P. Christiansen under the date of Tuesday, April 18, 1911, it shows that he and his companion went contacting door-to-door for three hours and visited 152 homes. A total of eighty-three people answered the door, but no gospel conversations took place. However, he recorded distributing 152 missionary tracts, indicating that he and his companion left some kind of literature at every residence they tried to contact. He also attended two meetings (one was an MIA meeting, but he did not indicate what the other one was), and he studied for five hours. It was not the most successful proselytizing day, but it was one well spent. Additional brief journal-like entries in Elder Christiansen’s record book include the following: “Helping secretary of the mission at Korsgade #11.” “Finding a new home in the afternoon.” “Finding a place to baptize in the ocean—helped out at the office.” “Attended a Methodist meeting.” “Got our pictures taken C. F. N. O. [the abbreviated names of the elders] Pres. Jensen [sic] and me.” “Riding train from Odense to Copenhagen.” “Hunting addresses for new elder.” “Got a place to hold open meetings.” And, sadly, “Funeral at Vestre Kirkegaard ‘Neilsen’s child.” Sickness took its toll on the missionaries and the work. From Friday, April 12, to Monday, April 22, 1912, Elder Christiansen’s book contains eleven consecutive entries, “Sick in bed.” Finally, under the date of May 15, 1912, is recorded, “Bid Andrew Jensen [sic] good Bye,” the very day President Jenson left to return to the States (see fig. 7).

There was no official preparation day for the missionaries, although Saturdays were usually the time when the elders attended to things such as writing home, taking baths, getting haircuts, shopping, cleaning their apartments, and washing clothes. Another entry in Elder Christiansen’s record book under the date of Saturday, May 13, 1911, shows that on this day, he visited Copenhagen’s famed Tivoli Gardens, one of the oldest amusement parks in Europe and in the world. One might expect that most Mormon missionaries who labored in the capital city enjoyed the park from time to time. [18]

Figure 7. Elder Aaron P. Christiansen's record book for the Scandinavian Mission, April 1911. Christiansen served in the Scandinavian Mission from October 26, 1910, to October 31, 1912. The book is in the possession of Alexander L. Baugh, a grandson of Elder Christiansen.

Figure 7. Elder Aaron P. Christiansen's record book for the Scandinavian Mission, April 1911. Christiansen served in the Scandinavian Mission from October 26, 1910, to October 31, 1912. The book is in the possession of Alexander L. Baugh, a grandson of Elder Christiansen.

Missionaries could expect transfers, new assignments, and changes in companionships. It appears that in most instances, however, after a missionary received his initial assignment, if he was assigned to labor in Denmark, he remained in Denmark his entire mission. The same was true for those assigned to Norway. Missionaries with ancestral roots or relatives living in Denmark and Norway were also encouraged to find and visit their family members.

Missionary activity was greatest during the warmer months of the year, when the days were considerably longer. During the summer months, meetings were held late and lasted late—sometimes until midnight. In the winter months, the elders proselytized in the major cities and communities, but in the summer they extended their range of activity to more rural areas. In the Trondhjem conference in Norway, the northernmost area of the mission (and considered the northernmost branch and conference of the Church in the world), missionary work during the winter came to a near standstill. Yet the summer months offered over twenty hours of daylight, thus enabling them to increase their missionary efforts. [19]

Mission Visitors

As noted previously, Andrew Jenson loved sightseeing and visiting new places and took advantage of every opportunity to mix missionary work with a little pleasure. In July 1909, six months into his presidency, President Anthon H. Lund, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, and his wife, Sarah Ann, came to Denmark for a short visit. President Lund, a close friend of Jenson’s, was a native Dane, born in Aalborg in 1844, making his visit a homecoming. Lund was accompanied by Charles W. Penrose of the Quorum of the Twelve and president of the European Mission, and his wife Romania. It was also on this occasion that Jenson’s wife Emma and daughter Eva traveled from Utah to visit for a few weeks. Another daughter, Eleonore Jenson Reynolds (a daughter from Jenson’s first wife, Mary, who died in 1887), who was studying music in Berlin, also joined the group. It is significant to note that both of Jenson’s wives, Emma and Bertha, lived in Utah during the three years he presided over the Scandinavian Mission. This is probably because he did not want to arouse any sort of controversy with their presence, since they were plural wives.

After visiting the Saints for a week in Jutland, the group traveled to Norway, where they held meetings in Christiania (Oslo) and Bergen. At this point, President Lund’s party left the group and traveled to Stockholm, while the Jensons and the Penroses traveled to Trondhjem and then to points even farther north. After leaving Trondhjem, the excursion essentially became a three-week sightseeing tour, although upon arriving at a port or village, the party sought out the missionaries and some of the local members and met with them briefly. This was the time of year to see the northern Norwegian coast and enjoy what nature had to offer. In his personal record, Jenson noted crossing into the Arctic Circle, visiting Hammerfest (the northernmost city in the world), passing the Nordkap (a jut of land marking the northernmost point in Europe), and finally arriving at Vardø (a small community on an island off of Norway’s northeastern peninsula). There they met with Elders Heber J. Hansen and Karl J. Knudsen, the two Mormon elders serving there, and Marie V. Kofod, the only member of the Church in the village. At Vardo, they visited a fortification erected in thirteenth century and held a meeting where Jenson’s daughters entertained 250 local townspeople by singing and playing the piano for them. On the return trip, Jenson enjoyed something that he had always wanted to experience. Under the date of July 23–24, 1909, he wrote:

I am writing these lines while sitting in the beautiful light of the midnight sun. I have watched on the deck of our steamer since 11 o’clock sitting by the side of Emma, Eleonore, and Eva. Not a cloud has hidden the sun from our view for a single moment. We have certainly enjoyed the sight. . . .

For many years I had desired to see the midnight sun, and now my wish was gratified. I remarked to Pres. Penrose that I had prayed for the clouds to lift and the sun to come out. In turn he told me that he also had prayed, and we all felt very thankful for what we had seen. [20]

After arriving at Narvik, the party went by train through northern Sweden, down the coast to Stockholm, and then by steamer back to Copenhagen. This was a fascinating trip for Jenson, who was thrilled to enjoy the beauty and sights of Norway’s northern coast and Sweden’s landscape with his wife and daughters and the Penroses. [21]

In 1910 and again in 1911, Mormon Apostle Rudger Clawson, who had succeeded Charles W. Penrose as president of the European Mission, accompanied President Jenson on two separate tours of the mission. From June 28 to July 19, 1910, they spent three weeks together visiting each of the six conferences in the mission and holding special meetings with the Saints. [22] A similar tour took place the following year (June 6–23, 1911). [23]

However, the most significant visitor to the mission was a visit in 1910 from none other than President Joseph F. Smith. President Smith was accompanied by his wife Mary T. Smith and son Franklin R. Smith; Charles W. Nibley, the presiding bishop; his wife Julia B. Nibley, and their two daughters. The party arrived in Copenhagen on July 27, 1910, where a meeting at the mission office was held in their honor that night. The following day, they traveled by steamer to Christiania (Oslo), where they spent two days in meetings and sightseeing. Unfortunately, President Smith’s stopover was also somewhat untimely. Previously, Andrew Jenson had been appointed as a delegate to the International Peace Congress in Stockholm, Sweden, which was being held at the same time of President Smith’s visit. Jenson made the best of the situation, however. Leaving Christiania (Oslo), President Smith’s party traveled to Stockholm, where President Smith and Bishop Nibley were received and entertained by Peter Sundwall, president of the Swedish Mission. As a delegate to the conference, Jenson secured two tickets for President Smith and Bishop Nibley to attend the opening session of the Congress, after which Jenson left the convention to accompany the president’s party on their return to Copenhagen, where they remained until August 3. The occasion of President Smith’s visit to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden marked the first time a serving Church President had visited Scandinavia (see fig. 8). [24]

The very day of President Smith’s departure, Jenson left Copenhagen to return to Stockholm to attend the remainder of the International Peace Congress. At the closing banquet held for the delegates, Jenson was permitted to share some brief remarks. In spite of his interrupted attendance, he felt his presence at the convention was worthwhile. “I only listened and looked on at the general meetings,” he wrote, “but in our excursions I had many opportunities to become acquainted with prominent members of the Congress, and on several occasions discussed Utah affairs and ‘Mormonism.’ I made many friends and believe I left a good impression with them.” [25]

Figure 8. Photograph taken of President Joseph F. Smith and Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley at the Scandinavian Mission headquarters, Korsgade #11, Copenhagen, Denmark, August 3, 1910. The Church authorities are seated on the second row, beginning with Andrew Jenson (sixth from the left), followed by Franklin R. Smith (son of President Smith), Mary T. Smith (wife of President Smith), President Joseph F. Smith, Charles W. Nibley, Julia B. Nibley (wife of Bishop Nibley), and the Nibleys' two daughters. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection.

Figure 8. Photograph taken of President Joseph F. Smith and Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley at the Scandinavian Mission headquarters, Korsgade #11, Copenhagen, Denmark, August 3, 1910. The Church authorities are seated on the second row, beginning with Andrew Jenson (sixth from the left), followed by Franklin R. Smith (son of President Smith), Mary T. Smith (wife of President Smith), President Joseph F. Smith, Charles W. Nibley, Julia B. Nibley (wife of Bishop Nibley), and the Nibleys' two daughters. Photograph in the Aaron P. Christiansen photograph collection.

Jenson’s Illustrated Lectures

Andrew Jenson was a proselytizing president. Beginning in 1910 and continuing throughout his mission presidency, he went throughout Denmark and numerous cities and regions of Norway presenting illustrated slide lectures, showing sometimes upwards of 120 slides using a Sciopticon projector. Occasionally, Jenson would give his illustrated lecture as part of the spring or fall conferences held in Copenhagen, Aarhus, Aalborg, Christiania (Oslo), Bergen, and Trondhjem, but his main audience was always those who were not of the faith. His primary purpose was to promote a greater understanding of the Latter-day Saints and to disabuse the public mind concerning some of the falsehoods and misunderstandings about the Latter-day Saints. Anti-Mormon attacks stemmed primarily from the Church’s practice of plural marriage and the controversy surrounding the 1902 election and subsequent Senate hearings of Reed Smoot. Smoot, a Mormon Apostle, had been elected to the United States Senate, but his seat had been contested primarily because of evidence and testimony that the Church had not altogether abandoned plural marriage even though Church leaders had publicly declared in 1890 that they would do so.

Opposition against the Mormons came from the press, political circles, the Lutheran clergy, anti-Mormon rallies, and, perhaps most significantly, from the motion picture industry. Significantly, in October 1911, Nordisk Film, a Copenhagen film company and the world leader in the production of silent movies, released a feature film titled Mormonens Offer (A Victim of the Mormons). [26] In short, Danes and Norwegians were being bombarded with negative stereotypes about the Mormons, something Jenson hoped he could change by appealing to non-Mormon audiences through his illustrated lectures.

The title of Andrew Jenson’s presentation was usually something like “Utah and Her People,” although on occasion he would also lecture on the land of Palestine and discuss his experiences from his 1895 worldwide tour. [27] Tracing his travels during these years shows that he lectured in every region in Denmark, including the more sparsely populated island of Bornholm (twice), Falster, and the islands of Langeland and Ærø, south of Fyn. While he did not travel as widely in Norway, he gave the lecture in several dozen cities in that country. In August 1911, he and Elder Alma L. Petersen also visited Iceland, where they presented two lectures in Reykjavik. [28] All told, he lectured fifty times in 1910, thirteen times in 1911, and fifteen times in 1912 (seventy-eight times total). [29] At times, Oluf J. Anderson, editor of the Skandinaviens Stjerne, and other missionaries filled in for Jenson, using his materials and delivering a similar presentation. [30]

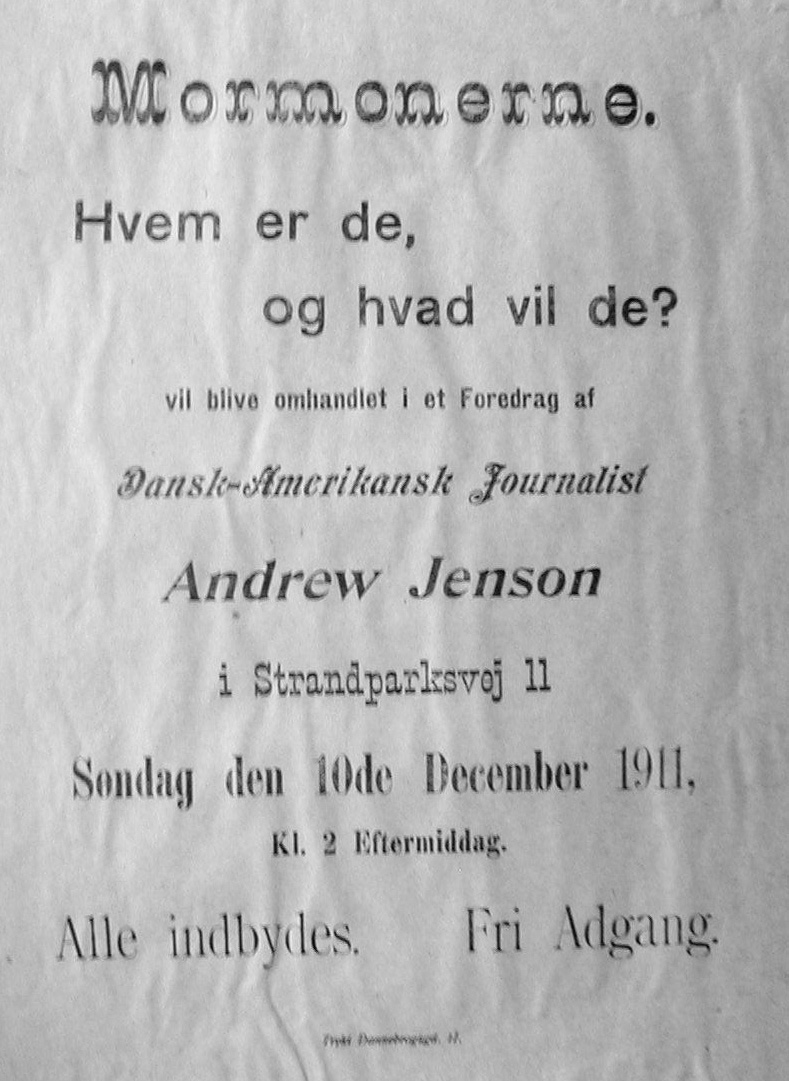

The missionaries played a vital role in the success of these lectures. Before Jenson’s arrival, the elders had to make arrangements to rent a hall and get permission from local city officials to hold the meeting. Advertisements were placed in the local papers, and the elders circulated handbills or flyers promoting the event (see fig. 9). Although it was technically a Mormon meeting, it was not necessarily advertised as such. In fact, in promoting the lecture, Jenson was not touted as being the president of the Scandinavian Mission, but rather a Danish-American journalist, which, given the many publications he had authored, he indeed was. To offset expenses, admission was generally charged (although not always), and because these meetings were generally so well attended, Jenson was frequently able to cover the cost of renting the hall and all of his traveling expenses, and even make a small profit. Reports of the lectures also appeared in the local papers and were generally favorable.

Figure 9. Handbill announcing that Andrew Jenson, a "Danish-American Journalist," will give a presentation on the Mormons at Stranparksvej #11 at 2:00 p.m., on December 10, 1911, city unknown. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh.

Figure 9. Handbill announcing that Andrew Jenson, a "Danish-American Journalist," will give a presentation on the Mormons at Stranparksvej #11 at 2:00 p.m., on December 10, 1911, city unknown. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh.

Things did not always go smoothly, however. In September 1910, the scheduled lecture at Frederiksværk did not go off as planned. Jenson explained:

On our arrival we soon learned that a biggoted [sic] little snipe of [an] official in the shape of a “Birkedommer” [a district judge] had forbidden the holding of the lecture. I hastened to that official’s office to find out the reason why and was confronted there by a big burly representative (Fuldmægtig) [an attorney] by the name of Buhrsch, who acted and spoke to me so insultingly that it soon came to hard words between us as I demanded causes for stopping the lecture, the hall having already been hired and paid for. At last he had to tell me that the “Birkedommer” had stopped it because we were “Mormons” and taught immoral doctrines. I demanded a refusal in writing, but he would not give it to me unless I applied for permission to lecture in writing. He however, refused me paper, thinking perhaps that it would be impossible for me to get the documents written elsewhere, but I hurried out of the building to a neighboring shop, obtained a sheet of paper, wrote the petition in good Danish and in polite language and presented it to “His Majesty the ‘Fuldmægtig.’” He soon became more gentlemanly in his behavior and asked me for time to consult the parish priest. Just imagine a civil officer consulting a parish priest for permission to hold a public meeting! I surmised that the priest would do all he could to stop the lecture, and this proved correct. The “Fuldmægtig” soon returned and said he was sorry that he had to stick to the former decision. After consulting the priest he said he now would emphasize the instruction of the chief (Birkedommeren), but he condescended to give us his refusal in writing, the thing that I wanted. Armed with that and my own petition which might be serviceable for future use, I hurried back to the brethren at the hotel, telling them there would be no lecture that night, and so we returned to Copenhagen. At the mission office we had quite a laugh over the little episode, but I felt so annoyed over it that I could not sleep during the night. To be outwitted and defeated by a Lutheran priest was an experience that did not suit my temperament. [31]

In several cities, Jenson was denied permission to give his presentation. Through the assistance of a Church member by the name of F. F. Samuelsen, a member of the Danish Parliament, however, Jenson was able to meet with the government’s minister of justice, who instructed Jenson to refer to him any further instance where he was not allowed to give his lecture. [32] Although laws against religious intolerance were in place in both Denmark and Norway, the Church was an easy target for religious harassment and discrimination, often times from the civil authorities themselves. Whenever or wherever this occurred, Andrew Jenson was not afraid to take a stand against such activities, writing letters, issuing complaints, or meeting personally with government officials to ensure that the rights of Church members and the missionaries to worship or proselyte were secure. Jenson expected that opposition would come from a portion of the public sector and even from religious leaders, but he demanded from the government the right to hold property, assemble, worship, and proselyte under the law.

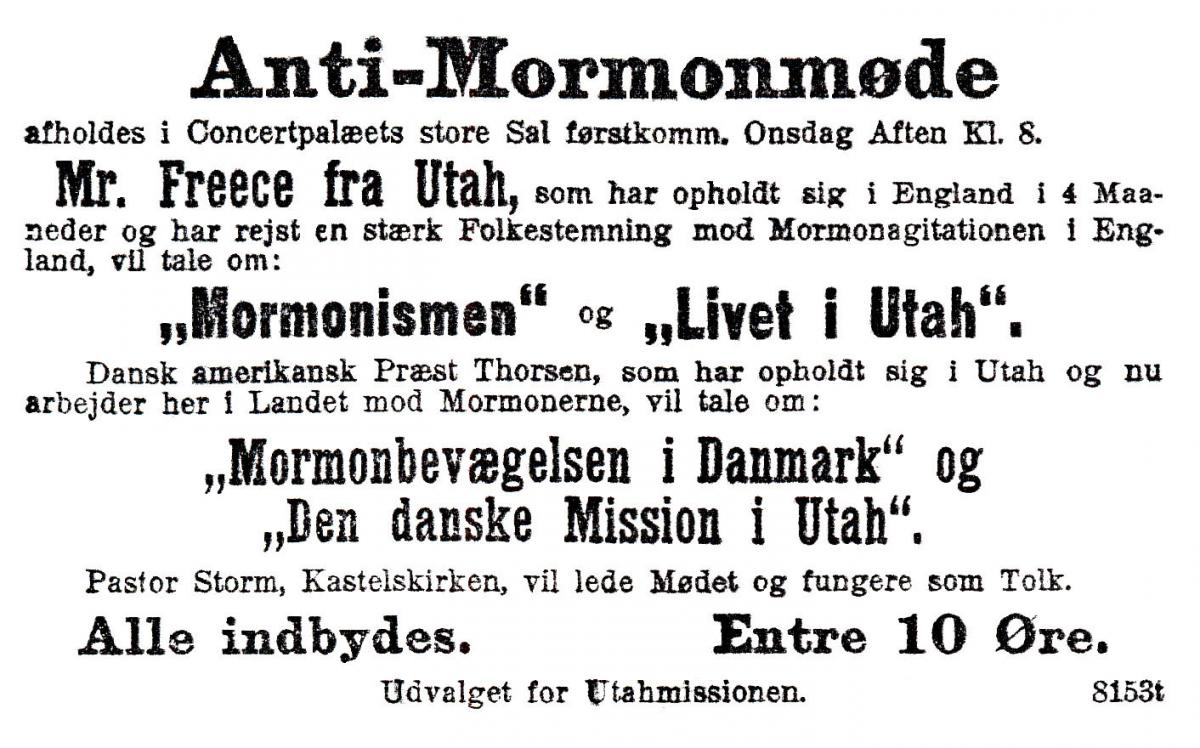

Jenson no doubt anticipated that his lectures would arouse some opposition. Joseph K. Nicholes, the mission secretary, reported: “Never, since the gospel was introduced into the Scandinavian countries 60 years ago, have the papers of Denmark been so agitated over the ‘Mormon’ question. . . . The success attending the delivery of [Andrew Jenson’s] lectures during the past year . . . have awakened all the powers of opposition.” [33] Reverend Johannes Thorsen, a Danish-American Lutheran minister, led the anti-Mormon charge. Significantly, in early 1911, Thorsen began presenting his own illustrated lectures against the Church. [34] In June, the minister was joined by Hans Peter Freece, the son of a Utah polygamist and an apostate Mormon. Freece had earlier conducted his own anti-Mormon crusade throughout Great Britain. [35] On June 21, a major meeting was held in Copenhagen that was attended by an estimated one thousand persons who heard Thorsen and Freece speak on Mormonism and life in Utah. A Mormon delegation, headed up by Jenson, Oluf J. Andersen, Anton Sorensen, and Joseph K. Nicholes, was invited to attend the meeting, but they were not permitted to speak. Afterward, however, they were invited to address the charges and arguments levied against them by Thorsen and Freece in a closed meeting consisting of several Lutheran priests and members of the press. Jenson and his colleagues ably defended the Mormon cause. Joseph K. Nicholes, the mission secretary, reported that of the newspapers in Copenhagen which reported on the meetings, only two contained reports unfavorable to the Mormons, while the largest paper in the city, Politiken, ended its report as follows: “The Mormons won sympathy by their calm, wise answers and when the meeting ended . . . there was only one meaning as to its results [and that is] Mr. Freece will do well if he packed his valise as soon as possible and return to America where the soil is no doubt more fertile for his agitation.” [36] Following the June 21 meeting, Freece returned to the United States, but Reverend Thorsen kept up his own campaign for several more months (see fig. 10). [37]

Figure 10. Advertisement for an anti-Mormon meeting featuring Hans Peter Freece and the Lutheran pastor Johannes Thorsen, Social Demokraten (Copenhagen, Denmark), June 20, 1911. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh.

Figure 10. Advertisement for an anti-Mormon meeting featuring Hans Peter Freece and the Lutheran pastor Johannes Thorsen, Social Demokraten (Copenhagen, Denmark), June 20, 1911. Courtesy of Alexander L. Baugh.

Major Accomplishments

It is not known when Andrew Jenson was notified by Church leaders in Salt Lake City of his release. [38] Martin Christoffersen, a native Norwegian who had immigrated to Utah and a seasoned missionary and leader, was chosen to replace him. Christoffersen arrived April 4, 1912, in time to accompany Jenson on his last mission conference tour. [39] This tour was one of joy and sorrow for both the Church members and the missionaries who celebrated President Jenson’s accomplishments, leadership, and personal friendship and simultaneously expressed sadness at his parting. At the Aarhus Conference, he “sang a song of his own composition, bidding farewell to the far north.” The conference at Bergen was capped by the dedication by President Jenson of the first meetinghouse acquired by the Church for the Saints in that city. [40]

If baptism numbers are a good indicator, Andrew Jenson’s presidency was remarkably successful. Annual records for the years 1909, 1910, and 1911 show a total of 1,146 convert baptisms—698 in Denmark (61 percent) and 448 in Norway (39 percent). [41] In 1910, the 245 baptisms in Denmark marked the highest number of baptisms since 1884, twenty-six years earlier. In Norway, that same year, the 188 baptisms marked the second highest number of baptisms since 1862. (In 1902, 190 were baptized in Norway, only two baptisms more.) Significantly, in 1912, the year Jenson returned home, baptisms in Norway remained about the same, but Denmark dropped off to 144, just over half of the previous year’s total (see table 2). [42] His efforts appear to have made a significant impact.

Table 2. Scandinavian Mission Baptisms, 1909–11

| Years | Denmark | Norway | Total |

| 1909 | 214 | 154 | 368 |

| 1910 | 245 | 188 | 433 |

| 1911 | 239 | 106 | 345 |

| Total | 698 | 448 | 1,146 |

Andrew Jenson’s major accomplishments of his Scandinavian Mission presidency may be summarized as follows: (1) In an attempt to strengthen the missionaries and the Saints, he held semiannual conferences in each geographical conference in Denmark and Norway, touring the entire mission each spring and fall (seven times total). In addition, he visited the conferences and branches of the mission, including the most remote areas, during other times of the year. During each of these excursions, he presided over hundreds of meetings for both the missionaries and Church members, teaching them about their duties and instructing them in the gospel. (2) By means of his illustrated slide lectures, he actively proselytized and presented the message of Mormonism to nonmember audiences throughout Denmark, Norway, and Iceland. (3) He met with government officials and ministers of justice to commit them to see that the religious privileges and rights of the Mormons and the missionaries were upheld. (4) Under his supervision, the mission published tens of thousands of missionary tracts, a new edition of the Pearl of Great Price in December 1909, and an additional 10,000 copies of the Book of Mormon in 1911. (5) And finally, in 1910, he was selected as the Mormon delegate to the International Peace Congress.

At the time of his release, Jenson wrote a letter to Elder Rudger Clawson, president of the European Mission, giving him a detailed report outlining his efforts during his mission presidency. He wrote:

Being about to take my departure from the shores of Europe to return to my home in the Rocky Mountains, I take pleasure in reporting to you, as the president of the European Mission, that since I took charge of the Scandinavian Mission in February, 1909, I have labored to the best of my ability to promulgate the principles of the everlasting gospel in Denmark and Norway, and have been ably and effectually assisted by faithful elders from Zion. I arrived in the mission February 11th, 1909, took charge of the same as successor to Elder Soren Rasmussen four days later, and tomorrow I expect to say goodbye to old Scandinavia and return home by way of Russia, Japan and Hawaii. During my presidency the elders in their capacity of missionaries have visited 1,442,421 houses of strangers, and distributed 2,933,700 books and tracts. The number of additions to the Church has been nearly 1,300 during these three years and three months that I have had charge of the affairs of the mission. Since I left home in Utah I have traveled about 64,000 miles, and delivered nearly 1,000 public addresses, including a number of illustrated lectures on Church history and affairs in Utah. We have labored in the midst of the most bitter opposition; never since the Scandinavian mission was opened in 1850 have the adversaries of the true gospel of Jesus Christ carried on such a crusade against our people and the elders as they have during the past year or two. Special lectures have been delivered by bitter anti-‘Mormons.’ . . . villifying us in the most scandalous manner. The Lutheran clergy and the press have gone hand in hand to create a bitter prejudice in the hearts of the people against us, and the columns of the newspapers have teemed with articles, partly original and partly deducted from old and stale articles which have circulated and been refuted in other countries many years ago. These things have advertised us freely, and our meetings have in many places been much better attended and more converts been made than would have been the case if we had been left alone.

During my presidency . . . we have printed 10,000 copies of the Book of Mormon, 10,000 copies of the Pearl of Great Price, 52,000 copies of “A Friend From the West,” 50,000 cards containing the Articles of Faith, and about 1,450,000 copies of “Rays of Living Light.”

I leave my present field of operations rejoicing and feeling thankful to my Heavenly Father that He has counted me worthy to labor so long and so successfully as a missionary in a foreign land, and I anticipate a happy reunion with family and friends in America. [43]

Elder Rudger Clawson praised Andrew Jenson’s service and commitment:

Having received an honorable release, President Andrew Jenson is returning to his home in Zion. He left Copenhagen on Wednesday, May 14th, 1912, and will visit Russia, Japan, and Hawaii on the homeward journey.

President Jenson presided over the Scandinavian mission from February, 1909, to May, 1912. He was an active, energetic worker, and his labors, which were of a highly important character, were attended with signal success. He was untiring in his devotion to the work of the Lord, and while supervising the labors of the missionary corps under his charge his voice was often heard in testimony of the truth in congregations of saints and strangers. . . .

President Jenson was ever in close touch with the president of the European mission, and held himself subject to counsel on all important matters submitted from time to time. He retires with the love and confidence not only of the elders, and saints of the Scandinavian mission, but also of his file-leaders, who have accepted his labors and released him in honor. [44]

Upon returning to Salt Lake City, Andrew Jenson immediately resumed his duties as Assistant Church Historian in the Historian’s Office. And although his mission presidency was officially over, for the next fifteen years, he kept close ties with the Scandinavian Mission—its members, missionaries, and leaders. During the years prior to his mission presidency, as well as afterward, he collected and compiled a large historical archive of documents associated with the Scandinavian Mission. From that collection he wrote a manuscript history of the mission covering a period of over seventy years (1850–1926). When the volume appeared in print in 1927 under the title History of the Scandinavian Mission, it became the first mission history ever published in the Church in book form. Jenson’s reflections about the book suggest that he considered the volume to be the capstone of his mission presidency. “It has been a labor of love,” he wrote in the preface. “It is the author’s tribute to his race—the stalwart sons and daughters of the North.” In a fitting conclusion, he expressed the hope that “after he shall have passed to the Great Beyond, he may still live in the memory of his fellow-men as one who, during his sojourn in mortality, endeavored to the best of his ability to tell the story of a God-fearing people, whose devotion, integrity and noble characteristics may serve as an inspiration to future generations.” [45]

Notes

[1] See Andrew Jenson, Autobiography of Andrew Jenson (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 449–52, 454 (hereafter cited as Autobiography). Jenson’s call to preside over the Scandinavian Mission was highlighted in “Editor’s Table,” Improvement Era, January 1909, 242.

[2] Jenson, Autobiography, 452–54. A report of Jenson’s travels to New York City also appeared in the Deseret Evening News. See Andrew Jenson, “Andrew Jenson Visits Historic Places,” Deseret Evening News, February 13, 1909, 24.

[3] Beginning in 1906, Jenson supervised the entire project.

[4] The remaining volumes appeared in 1914, 1920, and 1936.

[5] The most complete published autobiographical information on Andrew Jenson is in Jenson’s Autobiography, taken from his personal journals located in the Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Additional biographical works on Jenson include Louis Reinwand, “Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Historian, BYU Studies 14, no. 1 (Autumn 1973): 29–46; Keith W. Perkins, “A Study of the Contributions of Andrew Jenson to the Writing and Preservation of LDS Church History” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1971); Keith W. Perkins, “Andrew Jenson: Zealous Chronologist” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1974); Allen Kent Powell, “Andrew Jenson,” in Allen Kent Powell, ed., Utah History Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1984), 284; Keith W. Perkins, “Andrew Jenson: Zealous Chronologist,” in Donald Q. Cannon and David J. Whittaker, Supporting Saints: Life Stories of Nineteenth-Century Mormons (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young Univeristy, 1985), 83–100; Davis Bitton and Leonard J. Arrington, “Andrew Jenson: Mormon Encyclopedist,” in The Mormons and Their Historians (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988), 41–55; and Keith W. Perkins, “Jenson, Andrew,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 569–70. For a discussion of the Assistant Church Historians, see Richard E. Turley Jr., “Assistant Church Historians and the Publishing of Church History,” in Preserving the History of the Latter-day Saints, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; and Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 19–47. Turley’s discussion of Andrew Jenson is on pp. 24–26.

[6] Andrew Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1927), 411, 501. For a historical overview of LDS missionary work in Denmark and Norway, see Marius A. Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1966), 94–96; Gerald M. Haslam, Clash of Cultures: The Norwegian Experience with Mormonism, 1842–1920 (New York: Peter Lang, 1984); and Curtis B. Hunsaker, “History of the Norwegian Mission from 1851 to 1960” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1965). During the fifteen years when Denmark and Norway composed one mission, with Sweden as a separate mission, Denmark and Norway were sometimes called the Danish-Norwegian Mission even though that region was officially called the Scandinavian Mission.

[7] Andrew Jenson, “The Scandinavian Mission,” Deseret Evening News, March 13, 1909, 27.

[8] Andrew Jenson’s presidency went from February 15, 1909, to May 15, 1912, a total of three years and three months. In compiling the missionary and statistical information, I did not include the twenty missionaries called during the four and a half months Jenson served as president in 1912 (January through May 15, 1912) before he returned to Utah.

[9] See Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 426–34. Jenson’s history included the names of all the missionaries, the date they arrived in the mission, and generally the community or county where they were from.

[10] Aaron P. Christiansen is the author’s paternal grandfather. Both sets of Elder Christiansen’s grandparents were also native Danes who immigrated to Utah and spoke both Danish and English with their families.

[11] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 426–34. The frequency of having common or similar family surnames and given first names among Scandinavian populations resulted from patronymics. Oftentimes for individuals to be properly identified necessitated that they use their entire name or their initials. For example, the famous nineteenth-century Mormon artist Carl Christian Anton Christensen went by C. C. A. Christensen.

[12] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 387–89.

[13] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 223–24.

[14] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 415–16.

[15] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 394–95.

[16] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 492–93; see also “Bergen Conference,” Deseret Evening News, May 25, 1912, 6.

[17] The information regarding the mission conference format was summarized from a number of these published reports. In reviewing all of the issues of the Deseret Evening News, Improvement Era, and Millennial Star during the three-year period of Jenson’s mission presidency, the following number of reports/

[18] Missionary record book of Elder Aaron Parley Christiansen, Mayfield, Utah, in the author’s possession. Elder Christiansen was the author’s paternal grandfather. He was ordained an elder on September 4, 1910. One month later, on October 4, 1910, he received his call to the Scandinavian Mission. He arrived in Copenhagen on October 26, 1910, and served until October 31, 1912.

[19] David Christensen, “From the Land of the Midnight Sun,” Deseret Evening News, July 10, 1909, 26.

[20] Jenson, Autobiography, 463.

[21] Jenson’s entire account of the tour of the Jutland and Norway and the northern coast is in Jenson, Autobiography, 459–65. See also O. A. Garff, “President A. H. Lund and Party at Aarhus, Denmark,” Deseret Evening News, August 7, 1909, 27; Wilford H. Wilde, “President Lund Visits Bergen, Norway,” Deseret Evening News, August 7, 1909, 27; George E. Scow, “President Lund and Party at Aalborg, Den.,” Deseret Evening News, August 14, 1909, 26; and Henry O. Poulsen, “Scandinavian Mission News Notes,” Deseret Evening News, September 4, 1909, 26. Following this tour, from August 18 to 31, Jenson, his wife Emma, and daughters Eleonore and Eva traveled to Berlin, where Eleonore returned to resume her musical studies. From Berlin, Andrew, Emma, and Eva visited Holland and Belgium before visiting Paris and Versailles, where Jenson took leave of his wife and daughter. Jenson returned to Copenhagen on September 6, marking a period of nearly two months away from the mission headquarters most of the time. See Jenson, Autobiography, 165–66.

[22] Jenson, Autobiography, 468; and Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 428. See also “President Clawson in Scandinavia,” Millennial Star, July 14, 1910, 444–45; “President Clawson in Norway and Sweden,” Millennial Star, July 21, 1910: 460–61; Peter C. Rasmussen and LeRoy P. Skousen, “Prest. Rudger Clawson Visits Norway Capital,” Deseret Evening News, August 6, 1910, 26; and Joseph K. Nicholes, “President Rudger Clawson Visits Scandinavia,” Deseret Evening News, August 13, 1910, 26.

[23] Jenson, Autobiography, 479–81; and Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 432. See also Joseph K. Nicholes, “Scandinavian Mission,” Deseret Evening News, July 15, 1911, 30.

[24] See Jenson, Autobiography, 469–70; Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 428–29; and Joseph K. Nicholes, “Prest. Joseph F. Smith Visits Scandinavia,” Deseret Evening News, August 20, 1910, 26.

[25] Jenson, Autobiography, 472.

[26] For a discussion of the impact of A Victim of the Mormons, see Brian Q. Cannon and Jacob W. Olmstead, “‘Scandalous Film’: The Campaign to Suppress Anti-Mormon Motion Pictures, 1911–12,” Journal of Mormon History 29, no. 2 (Fall 2003): 45–46; and Jacob W. Olmstead, “A Victim of the Mormons and The Danites: Images and Relics from Early Twentieth-Century Anti-Mormon Silent Films,” Mormon Historical Studies 5, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 203–7. In October 1911, A Victim of the Mormons was shown in Stavanger, Norway. One Mormon elder reported: “The latest attack upon us is a poorly devised moving picture drama entitled, ‘Victim of the Mormons, a Drama of Love and Sectarian Fanaticism.’ In this drama the elders are pictured as being white slave handlers. Throughout, it is easy to observe the hypocrisy and lying nature of the whole affair, but for the time being it seems to have its effect upon the people, especially upon those who are prejudice and less thoughtful.” Hans J. Mortinsen [sic], letter to the editor, October 18, 1911, in “Messages from the Missions,” Improvement Era, February 1912, 331. Mormon missionaries held their own meetings, sometimes on the same evening A Victim of the Mormons was being shown, to explain who they were and the church they represented. A report from a Mormon elder serving in Haugesund, Norway, stated: “Some agitation against the ‘Mormons’ has grown out of the presentation of the moving picture drama, ‘A Victim of the Mormons.’ The elders took advantage of it, and on each night of the performance, distributed tracts and advertising matter of a meeting that they desire do hold on January 29, to answer the libels in the play.” The report continued: “Our hall was packed, there being over a hundred strangers present, besides the Saints, many being turned away because of lack of accommodations. For one and one half hours Elder Monson held the attention of the audience, showing that there is no foundation for the reports set forth in the play [motion picture]. He closed by explaining for what purpose the elders had come into this country; namely to preach the restored gospel of love and righteousness. The audience appeared to be well satisfied, and left with a new idea of ‘Mormonism,’ and many were heard to exclaim, ‘The Mormons cannot be as bad a people as represented after all.’ Many of the leading citizens were present, and expressed themselves as fully satisfied with our answer, and the result is that we have made a number of new friends. The outlook is bright for the future.” Lawrence C. Monson, letter to the editor, February 15, 1912, Improvement Era, June 1912, 745.

[27] See Millennial Star, March 3, 1910, 143; and Joseph K. Nicholes, “Mission News from Scandinavia,” Deseret Evening News, March 5, 1910, 30.

[28] See Fred E. Woods, “Andrew Jenson’s Illustrated Journey to Iceland, the Land of Fire and Ice, August 1911,” BYU Studies 47, no. 4 (2008): 101–16; Joseph K. Nicholes, “Scandinavian Mission,” Deseret Evening News, September 9, 1911, 24; and Andrew Jenson, “Iceland Conference,” Deseret Evening News, September 23, 1911, 29. Only two Mormon elders were on the island, Jacob B. Johnson (age sixty-eight) and Haldor Johnson (age fifty-five). Although Iceland technically came under the jurisdiction of the Scandinavian Mission, it appears that the missionaries essentially labored independently and had little contact with mission headquarters. It appears that no convert baptisms were made in Iceland during the administration of Andrew Jenson (1909–12). See “Manuscript History of the Iceland Mission, 1851–1914,” Church History Library.

[29] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 433.

[30] See Joseph K. Nicholes, “Popular Lectures on Mormonism in Scandinavia,” Deseret Evening News, March 26, 1910, 43; Joseph K. Nicholes, “Gospel Installed in Spite of Opposition,” Deseret Evening News, October 22, 1910, 27.

[31] Jenson, Autobiography, 474–75. A similar experience occurred in Gjentofte, where the Saints rented a large hall in the Gjentofte Hotel but were denied the privilege of holding the meeting. See “Copenhagen Conference,” Deseret Evening News, December 30, 1911, 27.

[32] Joseph K. Nicholes, “Scandinavian Mission,” Deseret Evening News, April 1, 1911, 31.

[33] Joseph K. Nicholes, “Copenhagen Conference,” Deseret Evening News, June 3, 1911, 34.

[34] See Joseph K. Nicholes, “Scandinavian Mission,” Deseret Evening News, April 1, 1911, 31. Elder Andrew Funk, serving in the Aarhus Conference, reported that in April 1911, “Pastor Thorsen is traveling around with magic lantern lectures for the purpose of ‘unveiling’ Mormonism.” See “Messages from the Mission,” Improvement Era, September 1911, 1062.

[35] Freece had been actively engaged in trying to secure legislation in the British Parliament prohibiting the LDS Church from proselytizing in Great Britain and restricting British Latter-day Saints from immigrating to the United States. The New York Times reported: “Hans P. Freece, the bureau’s special delegate, has arrived in London after a ten weeks’ tour in Scotland and the north of England, during which he succeeded in locating about 100 Mormon meeting places and 325 American Mormons engaged in inducing young women to emigrate to Utah. He also collected the signed statements of parents whose daughters had been enticed to America, and is in possession of irrefutable evidence that the Mormon church is in the habit of paying for the transportation of converts from England to Utah in violation of the United States immigration law. Mr. Freece entertains great hope of succeeding in getting a bill into Parliament prohibiting American Mormon elders from proselytizing in this country—in fact, the same law as that adopted by Prussia and Hungary not long ago. Although Mr. Freece declared his mission to be unofficial, he said he believed that should such a law, cutting off British-Mormon immigration to America, be passed, the Mormons would lose the control of Utah and a Democratic Representative might be expected to be sent to Congress at the next election.” “War on Mormons Is Waged in Britain,” New York Times, February 5, 1911. Freece’s activities led to an investigation of his allegations by the House of Commons: “Investigation of ‘Mormon’ activity in England will be made by the House of Commons. On the 6th of March, Secretary [Winston] Churchill stated that the attention of the government had been attracted to recent allegations that young girls were being induced to emigrate to Utah, and that the matter was causing deep concern. He therefore proposed to investigate the subject exhaustively, with a view to bringing out the exact facts. President Rudger Clawson, of the European Mission of the Latter-day Saints, welcomes the investigation, as do his co-laborers in that country, for they are confident there can be no other outcome before a fair judicial tribunal than a complete vindication of the actions of the Church. It has nothing to fear from an impartial and honest investigation, for its emigration affairs, as well as its missionary work in Great Britain, have been conducted in a manner that will bear the closest scrutiny. The Church has nothing to lose and everything to gain by the action which the home secretary has recommended.” “Passing Events,” Improvement Era, April 1911, 565.

[36] Joseph K. Nicholes, “Danish Conference,” Deseret Evening News, July 15, 1911, 30. See also Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 432–33; and Jenson, Autobiography, 480–81.

[37] Joseph K. Nicholes, “Danish Conference,” Deseret Evening News, October 21, 1911, 31. Missionaries in Norway reported that a man named Jansen Fuhr created a stir when he began presenting illustrated lectures on Utah and the Mormons. Two Mormon missionaries reported: “Friends who visited the lectures obtained a very different idea of the ‘Mormons’ from the pictures than from the lectures. His pictures showed that the ‘Mormons’ were an intelligent class of people; his lecture, the contrary.” A. Wilford Nielson and Charles C Sorensen, letter to the editor, August 18, 1911, Improvement Era, November 1911, 87. See also Hans J. Mortinsen [sic], letter to the editor, October 18, 1911, Improvement Era, February 1912, 330; and Junius M. Sorensen and Ernest A. Jensen, “Norway Conference,” Deseret Evening News, July 22, 1911, 31.

[38] In a letter from the First Presidency dated March 23, 1912, Jenson was told, “We have already written you the fact that Elder Martin Christoffersen has been called to succeed you as president of the Scandinavian Mission,” so he knew of his release at least by that time (see Jensen, Autobiography, 490).

[39] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 434–35.

[40] See Jenson, Autobiography, 492–94; P. Waldemar Nielsen, “Copenhagen Conference,” Deseret Evening News, May 4, 1912, 8; Stanley A. Rasmussen, “Aarhus Conference,” Deseret Evening News, May 11, 1912, 8; Lorenzo Swensen, “Christiania Conference,” Deseret Evening News, May 18, 1912, 9; and “Walter E. Fridal, “Bergen Conference,” Deseret Evening News, May 25, 1912, 6; Robert H. Sorensen, “Conference in Copenhagen,” Deseret Evening News, June 8, 1912, 6.

[41] The “Manuscript History of the Iceland Mission, 1851–1914,” Church History Library, does not list any baptisms during the administration of Andrew Jenson (1909–12).

[42] “Statistics of the Danish Mission,” and “Statistics of the Norwegian Mission,” in Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, 534, 536; also “Statistical Report of the Scandinavian Mission,” Millennial Star, February 24, 1910, 123; “Statistical Report of the Scandinavian Mission,” Millennial Star, March 23, 1911, 189. Since Jenson presided over the mission for only four months in 1912 (January through April), I did not include the figures for 1912.

[43] Andrew Jenson to Rudger Clawson, in “President Andrew Jenson’s Release,” Millennial Star, May 30, 1912, 348–49. I have standardized the use of quotations marks.

[44] “President Andrew Jenson’s Release,” Millennial Star, May 30, 1912, 349.

[45] Jenson, History of the Scandinavian Mission, iv.