Richard O. Cowan, "'Called to Serve': A History of Missionary Training," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 23–44.

Richard O. Cowan was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this book was published.

Even before the Church was organized, the importance of missionary preparation was understood. As early as May 1829, the Lord instructed Hyrum Smith, “Seek not to declare my word, but first seek to obtain my word, and then shall your tongue be loosed; then, if you desire, you shall have my Spirit and my word, yea, the power of God unto the convincing of men” (D&C 11:21).

Early Missionary Training

At first, the missionary training emphasis was on self-preparation in gaining an understanding of the scriptures and doctrines of the Church. Then, in 1832, a revelation directed Joseph Smith to organize the School of the Prophets, in which elders could “teach one another” in the gospel and other subjects that they might “be prepared in all things” for their callings (D&C 88:77, 80). The Lord expected the elders to “study and learn, and become acquainted with all good books, and with languages, tongues, and people,” and he declared, “It shall come to pass in that day, that every man shall hear the fulness of the gospel in his own tongue, and in his own language, through those who are ordained unto this power” (D&C 90:15, 11). The School of the Prophets began meeting at Kirtland in 1833 under the direction of Joseph Smith. A similar activity commenced that same year in Jackson County, Missouri, under the leadership of Parley P. Pratt and was known as the School of the Elders. The prime purpose of both schools was to prepare missionaries for their service. [1] The Seventies’ Hall, which opened at Nauvoo in 1844, served the same basic purpose.

As missionary work grew during the mid-nineteenth century, missionaries received helpful training from a variety of sources. One example was in Hawaii, where in 1853, Jonatana Napela, a district judge on the island of Maui, conducted a two-month language school for the American missionaries, providing room and board in his own home. For several hours each day, Napela had the missionaries read aloud from the Bible to become familiar with the sounds and meaning of the Hawaiian language. [2] Over a century later, the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah, would employ similar methods.

As Church schools were founded during the later nineteenth century, they soon created programs for missionary training. For example, in 1883, “missionary meetings” were added to the offering of the Theological Department at Brigham Young Academy (BYA) in Provo. Returned missionaries and even General Authorities addressed the young men who were students there. By 1894, missionary classes at BYA were well attended. In 1899, the academy’s president, Benjamin Cluff Jr., noted, “It is often asserted by missionary presidents that many of our young men who are called to preach the gospel are wholly, or in part, unprepared, not because they have not a strong testimony, but because they are ignorant of the principles of the gospel and of the scriptures.” He therefore offered to organize a program at Brigham Young Academy at no additional charge to the Church. The First Presidency approved such a course being offered at several Church schools. [3]

Participation in this program was available only to those called by the First Presidency. All were required to present at registration a recommend from their bishop that entitled them to free tuition in the missionary-oriented core of classes. These classes included instruction in theology, public speaking, vocal music, language, penmanship, correspondence, and the conducting of meetings. Mission presidents enthusiastically praised the results of this training. Elias S. Kimball, president of the Southern States Mission, described Church schools as “the natural nurseries of missionaries, educating the mental and spiritual alike.” He believed that young men entering the mission field with such preparation were far in advance of those who had “not been blessed in a similar way.” [4]

This was only the beginning of the academy’s effort to prepare young men and women for missionary service. In the spring of 1902, President George H. Brimhall asked Orin W. Jarvis, a returned missionary, if he would take charge of the Missionary Department soon to be organized at Brigham Young Academy. Jarvis declined the offer, feeling inadequate for the position and preferring to remain a student, but he soon served in the calling anyway. He later explained how he was set apart for this calling he had tried to decline:

Nothing further was said about this matter until in September of 1902 when I was notified to report immediately to the president’s office. I did so, wondering what complaint may have been lodged against me that would necessitate my being ordered to the “grill.” As I entered the room, President Brimhall grabbed me by the arm and without further explanation marched me into his private office, and sat me down in a chair and remarked to another man, whose back was toward me, “Here, President Smith, is the young man about whom I was talking.” Without further ado, President Joseph F. Smith placed his hands upon my head and set me apart to preside over the Brigham Young Academy Missionary Department. [5]

The course outline for the class specified that all participants “must consider themselves on a mission as truly as if called into the field, or in other words they must consider themselves, so far as character and deportment are concerned, as representatives of Jesus Christ.” [6]

By 1902, other similar missionary preparation classes commenced at Ricks College and at the LDS University in Salt Lake City. At LDS University, three evening sessions per week were addressed by Elder B. H. Roberts and received a greater response than anticipated. The Articles of Faith, by James E. Talmage, was the text, and emphasis was placed on the Bible. Tuition was free, but participants had to be recommended by their bishops. An announcement for the course promised that students would receive “thorough and systematic training in the principles, doctrine, and order of discipline of the Church,” and that the sessions would provide “intellectual exercise and spiritual inspiration.” [7] An added feature was training in music by Evan Stephens, the well-known composer of LDS hymns and conductor of the Tabernacle Choir.

The Salt Lake Missionary Home

During the early 1920s, Church leaders expressed concern for the welfare of missionaries who came to Salt Lake City to be endowed and set apart. David A. Smith, a counselor in the Presiding Bishopric, recommended that the Church establish a special home for these missionaries where a proper environment could be maintained. Anthony W. Ivins, a counselor to Heber J. Grant in the First Presidency, lamented, “I think it’s a shame that our boys are permitted to come to this city and wander around as they are doing. It seems to me that we should have some place where we can take care of them and look after them while they are in the city.” [8] On October 8, 1921, a committee of the Twelve met with mission presidents who had come to general conference, and this group considered the advisability of having all missionaries “undergo two weeks training on the temple block under the direction of the bureau of information.” [9]

In May 1924, the First Presidency approved a “Church Missionary Home and Preparatory Training School.” An advisory committee was at first headed by Bishop Smith but soon came under the direction of Elder David O. McKay of the Quorum of the Twelve, who had recently returned from presiding over the European Mission. The Church bought a home, originally built for one of Brigham Young’s daughters at 31 North State Street, then remodeled and furnished it to accommodate sixty-four missionaries, with space for an additional thirty-five if necessary. Each room had from two to six double beds. Sister missionaries were housed on the upper floor, while quarters for the elders were on the main floor and in the basement. The main floor also included rooms arranged for missionary meetings. [10]

About fifty persons, including General Authorities and members of the general boards, gathered in the home’s large front room for dedicatory services on Tuesday morning, February 3, 1925. President Anthony W. Ivins spoke of the need for a proper environment for giving the missionaries a good start; he believed that a correct attitude could help them avoid failure. Before offering the dedicatory prayer, President Heber J. Grant voiced his hope that the home might be a place where the scriptures would be read and appreciated. [11] Outgoing missionaries would stay at the home free of charge for one week. Here they could learn missionary methods from returning missionaries “by practical demonstration.” During the early twentieth century, missionaries typically had many responsibilities other than proselyting. Consequently, arrangements were made to take the outgoing missionaries through the various departments at the Church Office Building to learn methods for carrying out auxiliary and other Church activities. Particular attention was given to teaching them how to do genealogical research. [12]

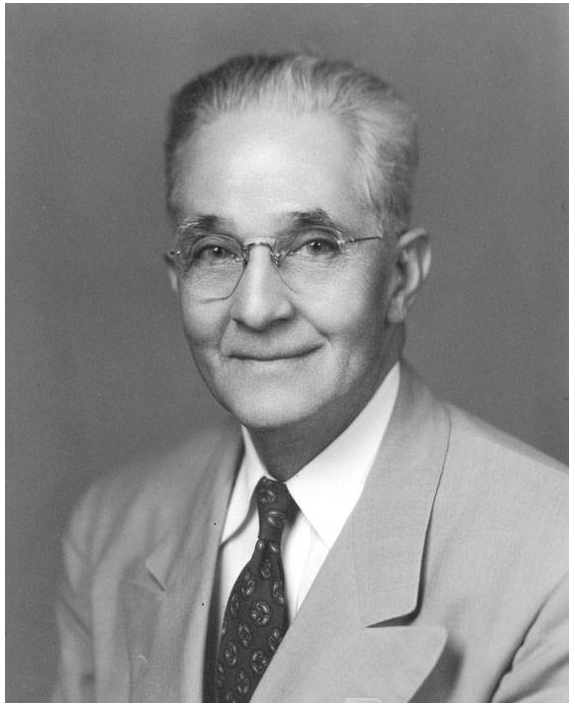

LeRoi C. Snow, the first director of the Salt Lake Missionary Home. Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

LeRoi C. Snow, the first director of the Salt Lake Missionary Home. Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

The first group of five elders entered the home on March 4, 1925. Early in 1926, the Missionary Home experience was extended to two weeks. The curriculum emphasized such matters as “singing, personal health and hygiene, gymnasium exercises and swimming, table etiquette and manners.” Missionaries were also “trained” in “proper association, dignified conduct, personal appearance, dress, order, [and] punctuality” and were encouraged to eliminate from their lives all “lightmindedness and loud laughter.” [13] LeRoi C. Snow, son of the late President Lorenzo Snow and the home’s first director, believed the greatest good accomplished by the home was in “helping the missionaries obtain the missionary spirit.” He was convinced that the elders’ concentrating their minds on the work of the Lord for two weeks, visiting the temple, seeing prayers answered, and having to express themselves before their associates “all increase faith, strengthen testimony, and increase eagerness to preach the gospel and bear testimony.” [14] In September 1926, the Church purchased the building immediately to the north of the Missionary Home, and the two homes were connected, thus providing additional sleeping accommodations and classrooms. [15] Later, two more neighboring homes were utilized. Over the years, the program of the Missionary Home in Salt Lake City was refined and trimmed to eight days, yet it retained the basic character first established under the direction of LeRoi C. Snow.

The older homes on North State Street were adequate to house the outgoing missionaries for over a third of a century, but with the great growth in the number of missionaries beginning with the 1950s, other facilities had to be found. In March 1962, the Missionary Home was moved into the former New Ute Hotel at 119 North Main (where the Conference Center would be built four decades later). This new facility could accommodate 280 missionaries on its three floors. [16] As the number of missionaries continued to mushroom, yet another larger facility was needed. In August 1971, missionary training shifted to the former Lafayette Elementary School at 75 E. North Temple Street, just across the street from the high-rise Church Office Building then nearing completion. The new facility accommodated the complete orientation program for up to about 380 missionaries. The only activities that needed to take place outside of the building were attending the Salt Lake Temple and eating meals a block away at the Hotel Utah or across the street at the Church Office Building cafeteria once it opened. [17] While these changes were being made in Salt Lake City, developments were unfolding forty-five miles to the south in Provo that would have a far-reaching impact on missionary training.

Language Training

As more and more countries opened to missionary work, the need to be acquainted with “languages, tongues, and people” increased. Although two years was the standard term of service for elders in the mission field, six months were added for those who needed to learn a foreign language. Early in 1947, Elder S. Dilworth Young of the First Quorum of the Seventy toured the Spanish-American Mission located in the southwestern United States. In his official report of this tour, Elder Young pointed out: “The Chief difficulty to good missionary work is the inability of the missionaries to speak Spanish. The president is under the necessity of keeping missionaries for a month, oftentimes, to give them even an idea of the language. Then they often go out to learn further from companions who know little more than they do. Three months of intensive study at Brigham Young University under Brother [Gerrit] de Jong [professor of languages] would make it possible for the missionaries to be of value in the field immediately. This period could well be part of the mission time, and would save time by the increase in usefulness of the missionaries upon their arrival in the field.” [18]

In December of that same year, the entire First Quorum of the Seventy sent a proposal on this same subject to the First Presidency. This document outlined many features of the program as it would be implemented some fourteen years later. The First Council recommended that Brigham Young University become the missionary training center for the Church, saying, “We feel that much more could be accomplished in a two-year period of time with three months of that time devoted to intensive training.” During these three months, “strict missionary discipline” should prevail as it had at the Missionary Home in Salt Lake City. Missionaries would attend classes of their own rather than mixing with the regular university students. A specially designed course of instruction would “give them a thorough understanding of the gospel and a definite preparation for missionary work.” The “new Army method of teaching foreign languages” could help the missionaries learn as much as possible during the brief period of three months. Other classes would focus on the customs and religions of the peoples the missionaries would meet. They could learn such practical skills as effective study habits, successful techniques in “tracting” (door-to-door contacting) and presenting the gospel discussions, good manners, and “refinement in general, now badly needed by many of the young people who represent the Church.” Those found to be “maladjusted because of sin could be worked with.” Those who were completely unfit—physically, mentally, or spiritually—for successful missionary service “could be directed into some other type of activity.” The First Council proposed that the Salt Lake Missionary Home be retained to give final instructions and to allow missionaries to receive their temple endowments before leaving for the field. [19]

Later, President Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency also championed the development of more effective methods of missionary work. At a meeting with BYU officials in Salt Lake City on September 6, 1960, he instilled a spirit of urgency into the missionary training program on campus. Thus for over a decade, leaders of the Church and officials of BYU had actively considered the advisability of creating a missionary language-training program on the BYU campus before it was ever implemented. These considerations did not lead to a tangible program until the fall of 1961, when an unforeseen problem provided the stimulus that moved the project from discussion to reality.

Ernest J. Wilkins, a Spanish professor and the first director of the Missionary Language Institute. Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Ernest J. Wilkins, a Spanish professor and the first director of the Missionary Language Institute. Courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

The specific circumstances for carrying these plans into action arose when missionaries began experiencing difficulties in obtaining visas to enter Mexico. Because the missionaries were experiencing a three-month delay and because they could stay no more than two years in Mexico, Joseph T. Bentley, a BYU administrator and former president of the Northern Mexican Mission, proposed in September 1961 the inauguration of a missionary-training program at BYU. This would provide means whereby newly called missionaries could learn missionary methods and the Spanish language while waiting to receive their visas. [20] The following month, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve approved this concept. Because missionaries going to Argentina were experiencing similar problems, they were also included. After spending the customary week at the Salt Lake Missionary Home, the first twenty-nine elders arrived in Provo on December 4, 1961, to participate in the newly formed Missionary Language Institute (MLI). Ernest J. Wilkins, a BYU Spanish professor, became its first director.

The initial schedule for these Spanish-language missionaries was quite demanding. The missionaries were housed at the old Roberts Hotel just over a mile from campus. Spanish-language recordings played quietly all night to provide an opportunity for subliminal learning as the missionaries slept. The elders then faced a full day of intense instruction at the Alumni House on campus. One wintry day, they released some pent-up tension by throwing snowballs at passing cars. One of the drivers was none other than BYU president Ernest L. Wilkinson. He wondered if some physical education activity might be a more appropriate way to release the missionaries’ energy. As a result of discussions that followed this incident, the nightly recordings were discontinued, and the missionaries settled into a routine including six hours of Spanish-language instruction every day with some time for physical activity in the gym each afternoon. [21] They attended meetings at the local Spanish-speaking branch each Sunday. Missionaries were also invited to participate in such campus activities as devotional assemblies, plays, and basketball games. Some of the elders reported that they felt like they were going to school rather than being on a mission. In 1962, the MLI moved into Allen Hall, adjacent to BYU campus. It provided a cafeteria and rooms for seventy-two missionaries.

Mission presidents in the field were very positive in their praise of the elders that came out of the MLI. Elder A. Theodore Tuttle of the Seventy, the General Authority supervisor for all South American missions, was convinced that the elders coming from the MLI “had an amazing facility in the language” and had acquired excellent study habits as well as a “well developed missionary spirit and ability to adhere to missionary discipline.” He appreciated their “desire to get out and go to work immediately.” [22]

In 1963, Church leaders concluded that the MLI should receive mission status. Consequently, the First Presidency set apart Dr. Wilkins as the first president of the new Language Training Mission (LTM). This gave him ecclesiastical authority over the missionaries during the period of their training. President Wilkins would continue to give leadership to the program for an additional seven years. Three days after President Wilkins was set apart, the LTM moved into Knight Mangum Hall, formerly a women’s dormitory on the southeast edge of campus. For the first time, the entire program—including living quarters, a cafeteria, classrooms, and offices—was housed under one roof.

An Era of Expansion

These new facilities made it possible for the program to expand. Church leaders had expressed a concern that training was being provided to relatively few missionaries and only in one language. As early as March 1963, Elders Gordon B. Hinckley and Boyd K. Packer had considered “ways of implementing a program that would make it possible to teach at Brigham Young University all of the 16 foreign languages now used by our missionaries in proselyting abroad.” [23] But this growth did not all come at once but rather over many years in carefully planned steps. First, with the June 1963 move into Knight Mangum Hall, all missionaries needing to learn Spanish and Portuguese started coming to Provo. German was added the next year, and other languages followed thereafter. The addition of each new language required careful planning for classrooms, instructors, teaching materials, and the scheduling of mission calls. Returned missionaries were ideal instructors because of their enthusiasm and knowledge of current practices of missionary work in the field. Foreign students attending BYU served as “informants” to help missionaries practice what they were learning. Employment at the LTM helped both of these groups to finance their BYU education. With continued growth, the ideal of having everything under one roof was once again out of reach.

Brigham Young University's Knight Mangum Hall, which housed the Language Training Mission. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Brigham Young University's Knight Mangum Hall, which housed the Language Training Mission. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

By 1968, six languages were being taught in Provo. That year, Church leaders decided to expand the program to include all the languages then being used by missionaries, which by that time had grown to eighteen. While the availability of foreign language professors and qualified returned missionaries was a major advantage of keeping all this training at BYU, Church leaders decided to utilize existing facilities on other campuses rather than constructing more buildings in Provo. The First Presidency announced that beginning in February 1969, “all missionaries going to foreign language missions will attend a two-month language training course following completion of their work in the [Salt Lake] Missionary Home and prior to their departure for their fields of labor.” Those needing to learn South Pacific or Asian languages would report to the Church College of Hawaii at Laie, and those going to Scandinavia or Holland would receive training at Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho. Those learning all other languages would continue to do so in Provo. [24] Those not needing to learn a new language would continue to receive their orientation at the Missionary Home in Salt Lake City.

The continuing growth in the number of missionaries made this solution only temporary. When the number of missionaries coming just to Provo increasingly overflowed available facilities, a committee headed by Joe J. Christensen, associate commissioner of Church Education, was appointed to consider the future of language training in the Church. In 1972, this committee recommended that all missionaries needing to learn a foreign language go to Provo because of its proximity to Church headquarters and because of the resources of BYU. [25] Later that year, commissioner of Church Education Neal A. Maxwell noted that accommodations at BYU were becoming increasingly inadequate, so he recommended construction of new facilities for missionary training. In December 1973, the First Presidency announced plans to construct a new Language Training Mission (LTM) complex at Brigham Young University and “to centralize training for all foreign language missions into the new Provo complex.” [26]

Ground was broken in 1974 for the new facilities under the personal direction of Ezra Taft Benson, President of the Quorum of the Twelve. While the new complex was still under construction, the separate LTMs in Hawaii and Idaho were discontinued in 1975 and 1976, respectively. With all missionaries once again coming to Provo, for a time there was severe overcrowding; some needed to be housed in BYU campus dormitories or even in area motels. Therefore, everyone eagerly looked forward to the new complex of over a dozen buildings that would include administrative offices, a cafeteria, classrooms, and dormitories to accommodate thirteen hundred missionaries.

The move into the new facility was well coordinated. On the evening of August 1, 1976, missionaries in Knight Mangum Hall were instructed to pack their belongings and were given colored baggage tags identifying the building into which they would be moving. The next morning, they went to classes as usual while moving crews from BYU transferred all the missionaries’ luggage to the new complex. That evening traffic was diverted to one side of Provo’s 900 East, while over nine hundred missionaries walked together to the new complex singing “Ye Elders of Israel.” One observer recalled, “It was like an army of God marching to the new Language Training Mission.” [27]

President Spencer W. Kimball dedicated the new complex on September 27, 1976. He said, “Now we dedicate all these buildings, our Heavenly Father, for the rich program which has been established, that from here may go the gospel, the testimony of thy Son, the testimony of the Prophet Joseph and that the work may go forward [so that] every nation, kindred, tongue, and people may hear the word of the Lord in their own language.” [28] By the time these buildings were dedicated, the Church’s missionary force had grown to the point that a “phase two” was already being planned. It would be completed two years later.

The Provo Missionary Training Center, originally dedicated as the Language Training Mission on September 27, 1976. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The Provo Missionary Training Center, originally dedicated as the Language Training Mission on September 27, 1976. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The Language Training Mission Becomes the Missionary Training Center

Once all language instruction for missionaries was centered in Provo and as other broader benefits of this training were increasingly appreciated, Church leaders considered the possibility of combining this language instruction with the orientation in Salt Lake City. The First Presidency decided that beginning on October 26, 1978, all missionaries would go directly to Provo for training and the Salt Lake Missionary Home would be closed. [29] Orientation for English-speaking missionaries was also extended from five days to four weeks. Because the title “Language Training Mission” no longer fully described the scope of the program, its name was changed to “Missionary Training Center” (MTC).

The orientation program for missionaries at the new MTC was strengthened. General Authorities began coming each week to speak at the Tuesday evening devotionals. Even Church President Spencer W. Kimball came two years in a row to be with the missionaries on Christmas Day. Missionaries were grouped into branches for worship services. Branch presidents played a key role by interviewing and counseling missionaries on an individual basis. As the number of missionaries continued to grow and since accommodations were increasingly crowded, it became impossible to always assign missionaries learning a particular language to a specific residence hall floor. Nevertheless, efforts to group missionaries by language have continued.

During the 1960s and 1970s, missionaries memorized their presentations. This meant that a major focus in missionary training was on memorizing the discussions, totaling over eighteen thousand words. Beginning in 1980, in order to avoid rote teaching, the discussions were modified, and missionaries were authorized to present portions of each lesson in their own words. This meant that training could place more focus on gospel study and teaching skills. To help missionaries with learning disabilities, the Teaching Resource Center (TRC) was created. TRC personnel developed a simplified version of the discussions, which became the basis for many discussion translations and eventually became the standard even in English discussions. With the reduction in the amount of material to be memorized, the length of the stay for English-speaking missionaries was shortened in 1981 from four to three weeks.

At this same time, specialized training programs were developed to meet unique needs. Beginning in 1981, a separate training program was devised for senior missionaries, with a curriculum based on learning patterns and expectations designed for older individuals. Rather than having to memorize the discussions verbatim, they were taught how to perform simple language tasks. The daily schedule allowed more time for individual study. Those with additional assignments, such as welfare, activation, visitor’s centers, or work in mission offices, also received specific instruction. In 1982, an outline was adopted that enabled missionaries to study various gospel topics as they read the standard works sequentially. During the early 1980s, Church and MTC officials were increasingly concerned about the quality of preparation received by Latter-day Saint youth before coming to the MTC for training. MTC personnel worked closely with BYU religion faculty members to develop a new missionary preparation course to be taught throughout the Church Educational System. The course taught proselyting principles to be used in finding and teaching.

Extensive research revealed that most missionaries were not very skilled at adapting their mostly memorized presentations to the unique needs of each investigator. To remedy this, the missionary department staff developed training materials based on what they termed the “commitment pattern.” Missionaries were taught how to prepare people to feel the Spirit, invite them to make commitments, help them keep commitments, and assist them in resolving personal concerns that might impede their progress. In 1985, a new set of “less structured and more flexible” missionary discussions were introduced. They incorporated principles of the commitment pattern and introduced the subject of Christ’s Atonement in the first, rather than in the sixth, discussion. Soon afterwards, a separate publication, the Missionary Guide, was designed for companionship study in the field, helping missionaries to use the new lessons and commitment pattern properly. Topics in the missionaries’ gospel study program were rearranged to be in the same order as in the proselyting discussions. In June 1991, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve called for a “balanced effort,” simultaneously emphasizing conversion, retention, and activation. [30] Consequently, training at the MTC increasingly emphasized how missionaries should work with local Church members and leaders in providing support for converts following their baptism.

Because of the intensity of responsibilities carried by MTC presidents, their term of service was shortened in 1986 to two years. The Missionary Department worried that if each new leader altered training methods and business procedures, the stability of the whole organization would be challenged. To ensure continuity and stability, ecclesiastical and professional aspects of the MTC were separated. The MTC president was in charge only of ecclesiastical matters but still worked closely with permanent staff administrators over professional areas such as training or business.

The decision of which languages to teach at the MTC was made by General Authorities and not by the MTC. At first, missionaries were trained in languages only to prepare them for teaching in foreign countries around the world. Beginning in 1979, however, the General Authorities approved preparing missionaries for teaching minority groups in areas including the United States who were living away from their homelands. Within three years, programs for teaching Greek, Polish, Vietnamese, and Russian were added to the MTC curriculum. Church leaders anticipated that converts among these minorities might someday be the means of carrying the gospel back to their homelands—in many cases, lands where missionaries were not yet permitted to go. In 1980, twenty-seven languages were being taught, and by the year 2000, this number had jumped to forty-seven. Nevertheless, nearly half of all missionaries learning a new language were still learning Spanish.

The increasing number of languages forced the MTC to continually examine its language-instruction methods to be sure that they were as effective as possible. From the beginning, missionaries at the MTC had been encouraged to speak in the language they were learning. One observer noted how quiet things were when missionaries were first introduced to this requirement. In the mid-1990s, computerized Technology-Assisted Language Learning (TALL) helped missionaries learn how to complete typical daily activities in their target language.

Area Missionary Training Centers

In previous years, missionaries called from outside of the United States or Canada to serve in international areas had gone directly to their fields of labor without any orientation. Beginning in 1977, area missionary training centers were established in Brazil and New Zealand. Within five years, similar centers had also been established in Mexico, Japan, the Philippines, and Chile. Eventually, there would be over a dozen. At the outset, no language training was offered at these centers. The objective was to provide international missionaries with the same caliber of orientation as English-speaking missionaries being trained at Provo.

With overcrowding at the Provo MTC being a constant challenge, Church leaders considered the possibility of sending North American missionaries to these area MTCs for their training. In addition to relieving this overcrowding, this plan included more opportunities to interact with native speakers and participate in actual teaching experiences in the local culture. Beginning in 1997, missionaries going to Brazil participated in what came to be known as “phased training”—spending their first month in Provo and their second month at the MTC in São Paulo. They made important adjustments before entering the mission field by being introduced to the food, traditions, and other aspects of Brazilian culture while still being partially shielded from the full effects of culture shock. Mission presidents appreciated that these missionaries arrived in the field with a better command of Portuguese and without the jetlag that had followed trips directly from North America. Furthermore, training in Brazil cost only about half of what it cost in Provo. In 1999, similar programs were instituted at the newly constructed Madrid and Lima MTCs.

The concept of providing complete training “in country” was also instituted in 1999. North American missionaries assigned to serve in Great Britain went directly to the Preston MTC for the standard three-week training, bypassing Provo completely. The following year, the decision was made to take better advantage of the spacious São Paulo MTC by having North American missionaries go directly there for their full eight weeks of training.

While an increasing number of North American missionaries were receiving all or part of their training abroad, a different set of considerations led to some international missionaries being sent to Provo for their orientation. In 2009, training centers in Japan and Korea were closed because of economic reasons. It was less costly to fly missionaries to Provo for their three-week orientation than to maintain facilities and staff locally.

The Impact of Preach My Gospel

Meanwhile, a new proselyting guide had been introduced. It represented a major new emphasis in missionary work. President Gordon B. Hinckley and others were concerned that missionaries were not teaching as effectively as they could. “For many years now we have had a standard set of missionary lessons. Great good has come of this. . . . But unfortunately this method, in all too many cases, has resulted in a memorized presentation, lacking in Spirit and personal conviction.” The prophet was convinced that “missionaries should master the concepts of the lessons. But they should . . . teach the concepts in their own words under the guiding influence of the Holy Spirit.” [31] As a result, Church leaders examined ways to increase the missionaries’ effectiveness.

Under the direction of the General Authorities, a new missionary guide titled Preach My Gospel was developed and introduced in 2004. [32] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, who played a key role in creating the new plan, noted, “We felt that if the missionaries were more deeply converted themselves they would find their own best ways to convert their investigators.” [33] Elder Richard G. Scott was excited to report that this new guide had “ignited the minds and hearts of our missionaries, for it equips them to teach their message with power and to bear testimony of the Lord Jesus Christ and of his prophet Joseph Smith without the constraint of a prescribed dialogue.” Elder Scott testified, “Those who participated in its development are witnesses of the inspired direction of the Lord through the Holy Ghost in the conception, framing, and finalization of the materials in Preach My Gospel.” [34]

Preach My Gospel instructed missionaries to create their own teaching outline for each investigator: “You can teach the lessons in many ways. Which lesson you teach, when you teach it, and how much time you give to it are best determined by the needs of the investigator and the direction of the Spirit.” Missionaries were specifically instructed not to memorize the lessons. [35] They were instructed to work closely with Church members in identifying people to teach and then fellowshipping those who were baptized in order to “welcome new converts into the ward.” Church members were then to help new converts feel comfortable in Church meetings and help them become acquainted with a widening circle of new friends. [36] Training at the MTC was modified to give missionaries opportunities to practice these specific skills. In fact, in 2011, Stephen Allen, the managing director of the Missionary Department, reported that the department was “completely redoing the curriculum for missionary training centers worldwide.” [37]

From the Church’s beginnings, helping missionaries become more effective in discharging their divine responsibility has been a priority for Church leaders. Individual initiative has played a key role in developing specific programs. External factors have also provided opportunities for new efforts to be launched, and existing procedures have been modified to meet changing needs. In all of this, inspired leaders have given important direction and motivation in the past and will continue to do so in the future.

Notes

[1] Orlen C. Peterson, “A History of the Schools and Educational Programs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Ohio and Missouri” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1972), 20, 34.

[2] Fred E. Woods, “Jonathan Napela: A Noble Hawaiian Convert,” in Reid Neilson and others, eds., Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The Pacific Isles (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), 27; R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaii (Laie, HI: Brigham Young University–Hawaii Institute for Polynesian Studies, 1986), 29; Fred E. Woods, “The Most Influential Mormon Islander: Jonathan Hawaii Napela,” Hawaiian Journal of History 42 (2008): 135–57.

[3] Cited in Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., The First Hundred Years (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 1:271.

[4] Cited in Wilkinson, First Hundred Years, 1:272.

[5] O. W. Jarvis to Fern Eyring, March 12, 1954, quoted in Richard Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel in His Own Language (Provo, UT: Missionary Training Center, 2001), 8.

[6] Quoted in Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel, 8.

[7] “Evening Missionary Class,” Deseret News, January 6, 1902, 6; “Missionary Class,” Deseret News, October 26, 1905, 4.

[8] Le Roi C. Snow, “The Missionary Home,” Improvement Era, May 1928, 552–54; remarks by President Spencer W. Kimball at the dedication of the new Missionary Training Center complex, September 27, 1976. Fewer sister missionaries than elders were being called at this time than at present.

[9] Mission Annual Reports, 1922, MS, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[10] Journal History of the Church, January 17, 1925, 2.

[11] Journal History of the Church, February 3, 1925, 3.

[12] Journal History of the Church, January 17, 1925, 2.

[13] Snow, “Missionary Home,” 553.

[14] Snow, “Missionary Home,” 553.

[15] Journal History of the Church, September 9, 1926, 3.

[16] Arnold J. Irvine, “Missionaries Move In,” Church News, April 7, 1962, 8.

[17] “Remodeling for New Missionary Home Set,” Church News, October 24, 1970, 12; Jarrard E. Jack, “Go Unto All the World,” Church News, September 25, 1971, 8–9.

[18] Spanish-American Mission, 1947, in Reports on Mission Tours by General Authorities, MS, Church History Library.

[19] Unanimous report made by the First Council of Seventy to the First Presidency, December 3, 1947.

[20] Joseph T. Bentley to Marion G. Romney, September 20, 1961.

[21] Charles Panhorst, interviews by the author, November and December 2010.

[22] Cited in Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel, 27.

[23] Quoted in Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel, 29–30.

[24] First Presidency to mission presidents, January 3, 1969, quoted in Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel, 39–40.

[25] Summary Report of the Language Training Mission Study Committee, 1972, quoted in Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel, 46, 88–95.

[26] “Church Plans Center,” Church News, December 15, 1973, 3.

[27] Jeanne Larson Hatch, interview by Richard O. Cowan, August 24, 1982.

[28] Quoted in Cowan, Every Man Shall Hear the Gospel, 100–102.

[29] “Mission Training Shifts to Provo,” Church News, September 9, 1978, 10.

[30] First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve, “Fundamental Considerations in Proclaiming the Gospel,” June 1991; see also “Proclaiming the Gospel and Establishing the Church,” June 1998, official Church letters in author’s possession.

[31] Quoted in Richard G. Scott, “The Power of Preach My Gospel,” Ensign, May 2005, 29.

[32] Benjamin White, “A Historical Analysis of How Preach My Gospel Came to Be” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2010).

[33] Quoted in R. Scott Lloyd, “Fortunate to Serve in ‘Preach My Gospel’ Era,” Church News, January 15, 2011, 3.

[34] Scott, “Power of Preach My Gospel,” 30–31.

[35] Preach My Gospel (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), vii.

[36] Preach My Gospel, 216.

[37] Quoted in R. Scott Lloyd, “Teaching Missionaries How to Teach the Gospel,” Church News, January 15, 2011, 4.