What Is a Temple?

Richard O. Cowan

Richard O. Cowan, "What Is a Temple? Fulfillment of the Covenant Purposes," in Foundations of the Restoration: The 45th Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, ed. Craig James Ostler, Michael Hubbard MacKay, and Barbara Morgan Gardner (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 269-288.

Richard O. Cowan was a professor emeritus of Church history and doctrine, Brigham Young University when this was written.

The Latter-day Saints have become known as a temple-building people. Their understanding of the nature and unique mission of these sacred structures unfolded over the years. Hence, if they were asked at different times what a temple was, their answers would have likely been different. Elder James E. Talmage pointed out that “while the general purpose of temples is the same in all times,” there is still “a definite sequence of development in the dealings of God with man.” Therefore, “we may affirm that direct revelation of temple plans is required for each distinctive period of the Priesthood’s administration.” Consequently, Elder Talmage concluded that the temple buildings themselves are a tangible record of God’s unfolding revelations to his people concerning temple work.[1] This chapter will show how revelation guided the designing of latter-day temples, what the facilities of individual temples were designed to accommodate, how they were used, and how all these changes reflected the Saints’ unfolding understanding of the nature of temples.

In former dispensations, temples served two distinct functions. First, the Lord promised to reveal himself to his people in the portable tabernacle (Exodus 25:8, 22). Second, ancient temples were also where the people performed sacred priesthood ceremonies or ordinances such as sacrificial offerings (see D&C 124:38).

Both of these functions needed to be restored as part of the latter-day “restitution of all things” (Acts 3:21), but this restoration did not come all at once. The Lord had declared that he would “give unto the children of men line upon line, and precept upon precept, here a little and there a little” (2 Nephi 28:30; Isaiah 28:10). This principle was clearly reflected in the unfolding revelation of temple service in the present dispensation and the consequent design of early Latter-day Saint temples.

Restoration of Temple Worship Beginning at Kirtland

The first specific information about building a latter-day temple came in July of 1831 when the Prophet Joseph Smith learned that one was to be located at Independence, Missouri (D&C 57:1–3). He placed a cornerstone there early the next month, but the next step in temple building would come in Ohio rather than in Missouri a year and a half later.[2]

The Saints received their first real glimpse into the nature of temple service in connection with instructions concerning the School of the Prophets. Near the end of 1832, the Lord directed the brethren at Kirtland to build a “house” for this school (D&C 88:119). Only the worthy were to attend: “He that is found unworthy,” the Lord instructed, “shall not have place among you; for ye shall not suffer that mine house shall be polluted by him” (D&C 88:134; compare 97:15–17). Later, those who participated in the school were required to observe the Word of Wisdom and agreed not to divulge the sacred matters discussed there.[3] These requirements clearly anticipated practices that would later be associated with temple worship.

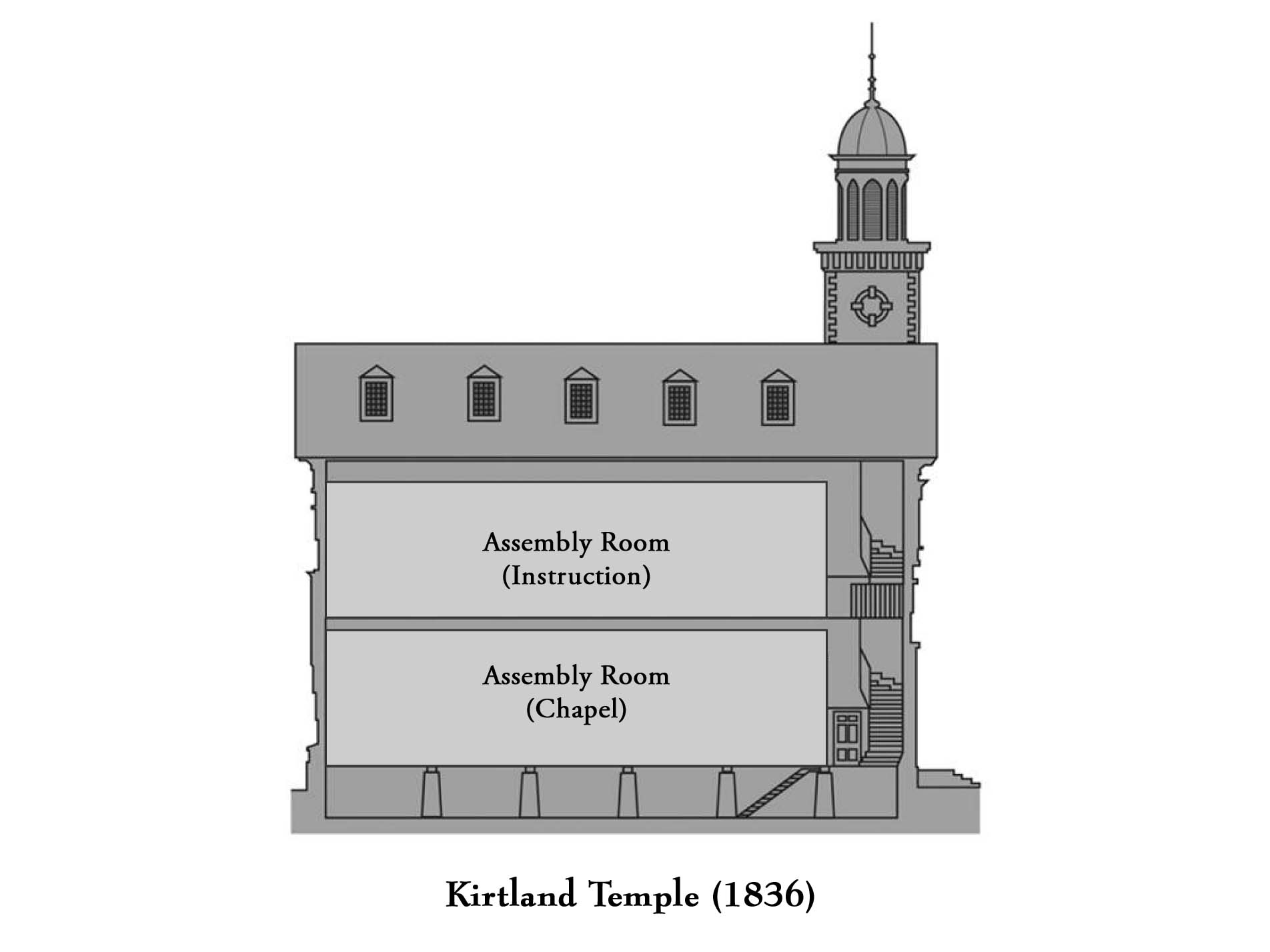

Further insights came by revelation the following June, when the Lord admonished the Kirtland Saints to move forward with the building of his house in which, he declared, “I design to endow those whom I have chosen with power from on high” (D&C 95:8). Historian David J. Howlett observed that receiving such a spiritual manifestation represented one Mormon response to the yearning of millennial or perfectionist evangelicals, who after their conversion wondered “if there were not more of God’s powerful grace yet to be experienced.”[4] The revelation instructed that the house should not be built “after the manner of the world,” but according to a pattern which would be made known to three brethren whom the Saints would appoint. Specifically, the temple’s “inner court” (main interior space) would have two levels. The main floor would be a chapel where the Saints might fast, pray, and partake of the sacrament. The second floor was to have another large room to serve as a school for those called into the Lord’s service (D&C 95:8, 13–17). Hence, the main spaces in the Kirtland Temple were intended for activities which were about the same as what was typically taking place in most church buildings of the time.

A conference of high priests met two days later to consider building the temple. In accordance with the Lord’s instructions, they appointed three men, the recently formed First Presidency, “to obtain a draft or construction” of the temple. Truman O. Angell, later one of the supervisors of temple construction, explained how the Lord impressively fulfilled his promise to show the building’s design. On an occasion when the presidency knelt in prayer, the building appeared before them in vision. “After we had taken a good look at the exterior,” Frederick G. Williams (the second counselor) testified, “the building seemed to come right over us.” This let them also view its interior. While subsequently speaking in the completed temple, President Williams affirmed that the hall in which they were convened coincided in every detail with the vision given to the Prophet.[5]

“Joseph not only received revelation and commandment to build a Temple,” President Brigham Young later affirmed, “but he received a pattern also, as did Moses for the Tabernacle, and Solomon for his Temple; for without a pattern, he could not know what was wanting, having never seen [a temple], and not having experienced its use.”[6] Elder Orson Pratt similarly testified, “When the Lord commanded this people to build a house in the land of Kirtland, in the early rise of this church, he gave them the pattern by vision from heaven, and commanded them to build that house according to that pattern and order; to have the architecture, not in accordance with architecture devised by men, but to have every thing constructed in that house according to the heavenly pattern that he by his voice had inspired to his servants.”[7]

In the light of this revealed “pattern” concerning Kirtland, the brethren promptly began developing plans for a similar but larger building for Independence, Missouri. They prepared a series of sketches as planning progressed. Even though the initial drawings were superseded, they were not thrown away because paper was scarce. (Over a century later, some of these preliminary sketches would be rediscovered as backing to which papyrus fragments had been glued for preservation.) Even these early drawings for the temple in Zion depicted features that would characterize the Kirtland Temple: the unique series of pulpits at each end of the main halls and box pews with reversible seating.

On June 25, 1833, Joseph Smith sent his plat for the city of Zion together with plans for the “House of the Lord for the Presidency” to the brethren in Missouri. This plan set forth the pattern of wide streets crossing at right angles, which would in later decades become a familiar and welcome characteristic of Mormon settlements. There were to be twenty-four “temples” at the center of the city assigned to the various priesthood quorums. The Prophet anticipated that these twenty-four buildings would be needed to serve a variety of functions such as meetinghouses, places of worship, and schools. Because all inhabitants of the city would be expected to live on a celestial level (D&C 105:5), all these buildings would fit the first function of temples—places of communication between heaven and earth.

A revelation received in August 1833 spoke of a similar but smaller complex of sacred buildings in the heart of Kirtland: The Lord’s house, another building “for the work of the presidency, in obtaining revelations,” and a third for printing the scriptures. These structures were to be of uniform size and, like the temple, were to be kept “holy” and “undefiled” (D&C 94:1–12).[8]

Even though the Kirtland Temple’s exterior may have looked something like the New England meetinghouses of the time, it was the revealed design of the interior that made the building truly unique. Typically, the two rows of windows on a church illuminated the main floor and balcony of a single large hall. In Kirtland, however, these windows were for the two main rooms, one above the other. Four levels of pulpits at both ends of these auditoriums were the unique feature of the Kirtland Temple. Block wooden initials on these pulpits helped Church members to understand the relative authority of various priesthood leaders, with Melchizedek at the west, and Aaronic at the east.[9] Seating in the main part of the hall was reversible so the congregation could face either set of pulpits. Painted canvas partitions or “veils” could be rolled down from the ceiling to divide the room into four quarters, enabling a separate meeting to be conducted in each area.

When the temple was completed, sacrament and other worship meetings convened in the large hall on the ground floor. The School of the Prophets and other instructional meetings were held on the second floor. Priesthood groups and leaders often met in the five small rooms on the attic floor which also served as classrooms. Thus, because the temple was the only church building in Kirtland, it was essentially a meetinghouse accommodating a variety of other functions, but there were no facilities particularly designed for ordinances. Specifically, Brigham Young later pointed out that the Kirtland Temple “had no basement in it, nor a font, nor preparations to give endowments for the living or the dead.”[10]

Still, remarkable spiritual experiences during early 1836 confirmed that the Lord accepted the temple. On January 21, Joseph Smith received the vision of the celestial kingdom in which he learned that “all who have died without a knowledge of this gospel, who would have received it if they had been permitted to tarry, shall be heirs of the celestial kingdom of God” (D&C 137:7). Even though sacred ordinances for the dead were not specifically mentioned on this occasion, this revelation did lay the doctrinal foundation for the work to which temples ultimately would be devoted.

These pentecostal experiences climaxed with the dedication of the temple on March 27, 1836. The dedicatory prayer, which had been given to the Prophet by revelation, petitioned that the Lord would accept the temple which had been built “through great tribulation . . . that the Son of Man might have a place to manifest himself to his people” (D&C 109:5). Specifically, the Prophet prayed that God’s “holy presence [might] be continually in this house,” and that all who enter might “feel [his] power, and feel constrained to acknowledge that [he] has sanctified it, and that it is [his] house, a place of [his] holiness” (D&C 109:12–13). The prayer then acknowledged that the Lord’s servants would go forth from the temple armed with power and testimony (D&C 109:22–23). One week later, on April 3, the Savior appeared to accept the temple, and the ancient prophets Moses, Elias, and Elijah restored keys of authority (D&C 110).

Hence, the Lord’s house in Kirtland fulfilled the first main function of temples: To be a place of revelation from God to man. “The prime purpose in having such a temple,” Elder Harold B. Lee explained, “seems to have been that there could be restored the keys, the effective keys necessary for the carrying on of the Lord’s work.” He concluded that the events of April 3, 1836, were “sufficient justification for the building of [this] temple.”[11]

Not long after such glorious experiences had lifted the Saints, however, the forces of apostasy and persecution increased. In less than two years, the faithful were compelled to flee from their homes and temple in Ohio. Most settled at Far West in northern Missouri. Here, the Lord once again commanded the Church to “build a house unto me, for the gathering together of my saints, that they may worship me.” Ordinances were not mentioned; they were still yet to be revealed. As at Kirtland, the temple was to be built according to a “pattern” which the Lord would show (see D&C 115: 8–10, 14). As had been the case at Independence (about eighty miles further south), persecution would also prevent construction of this temple.

Sacred Ordinances and the Nauvoo Temple

Fleeing from their persecutors in Missouri, the Latter-day Saints settled in western Illinois at a place they named Nauvoo, a Hebrew word meaning “beautiful.” Within two years, they began construction on yet another temple. Before this edifice was completed, sacred ceremonies or ordinances were restored which would be reflected in the temple’s ultimate design.

Joseph Smith first taught the practice of vicarious baptisms for the dead on 15 August 1840.[12] Almost immediately, Church members began receiving this ordinance in the Mississippi River in behalf of deceased loved ones.

Another ordinance taught at Nauvoo was the endowment. Some practices in the Kirtland Temple had anticipated portions of the endowment, but the more complete form of this ordinance was first given to a group of selected brethren on 4 May 1842 in the assembly room on the second floor of Joseph Smith’s red brick store in Nauvoo. Under the Prophet’s direction, this room was partitioned into areas representing stages in man’s progress back into the presence of God. Participants moved from one area to the next as the endowment instructions unfolded. Some historians note that several Latter-day Saints had become involved with freemasonry and that this may have helped them appreciate the idea of a building designed for special teachings and rituals. [13]

Among the other blessings revealed during these years was marriage for eternity. In May 1843, the Prophet instructed the Saints that in order to attain the highest degree of the celestial kingdom, one must enter this “new and everlasting covenant of marriage” (D&C 131:1–4). Two months later, he recorded a revelation outlining the great blessings promised to faithful recipients of this ordinance (D&C 132:7–19).

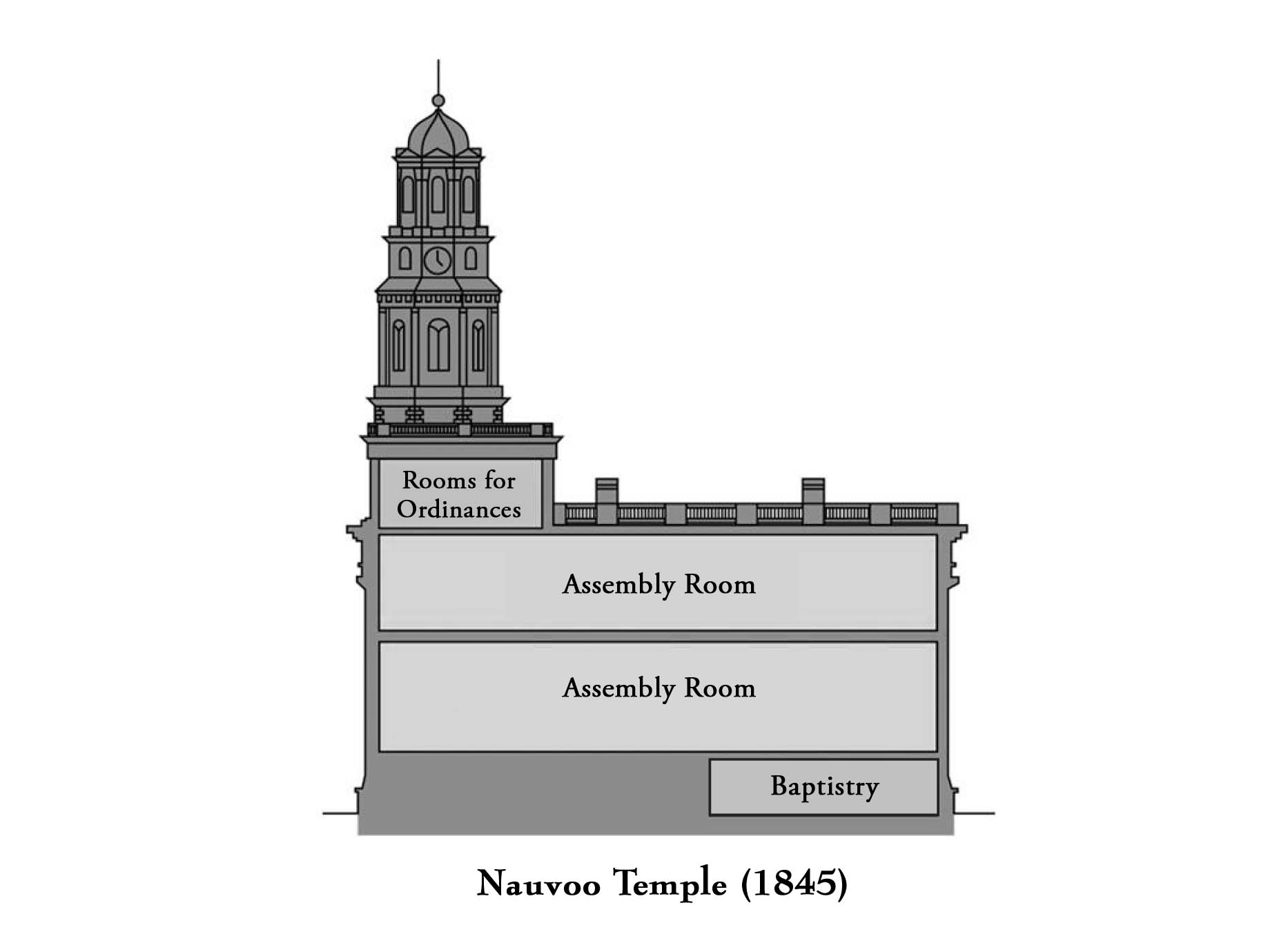

The Nauvoo Temple followed the basic concept of the Lord’s house in Kirtland, having two large auditoriums for general meetings. Still, reflecting the Saints’ growing knowledge about sacred priesthood ordinances, the temple would also include spaces for administering them. Early in August 1840 the First Presidency declared, “The time has now come, when it is necessary to erect a house of prayer, a house of order, a house for the worship of our God, [as well as] where the ordinances can be attended to agreeably to His divine will.”[14] A revelation received on January 19, 1841, directed Latter-day Saints to gather precious materials from afar and build a house “for the Most High to dwell therein. For there is not a place found on earth that he may come to and restore again that which was lost unto you, or which he hath taken away, even the fullness of the priesthood.” The revelation also insisted that ordinances such as baptisms for the dead belong in the temple, so Joseph directed the Saints to provide a font there (D&C 124:25–30). Hence, the Nauvoo sanctuary was to serve both functions of temples—being a place of contact between God and man and also a place where sacred priesthood ordinances could be performed.

As had been the case in Kirtland, Joseph Smith insisted that the basic plan of the Nauvoo Temple was a result of revelation. When architect William Weeks questioned the appropriateness of placing round windows on the side of the building, for example, Joseph explained that the small rooms in the temple could be illuminated with one light at the center of each of these windows, and that “when the whole building was thus illuminated, the effect would be remarkably grand. “I wish you to carry out my designs. I have seen in vision the splendid appearance of that building illuminated, and will have it built according to the se.”[15] The temple’s two large meeting halls had high, arched ceilings, leaving space for a row of small rooms between the arch and the outside walls, each room having one of the round windows. The temple also would include a baptismal font in the basement and facilities for the other sacred ordinances on the attic level.

In November 1841, only seven months after temple cornerstones had been laid, a font in the basement was covered by a temporary enclosure, and the members commenced performing baptisms for the dead there. In coming months, the prophet and apostles frequently officiated personally in the font. As the lower assembly hall was completed, conferences and other meetings were held there. A visitor to the Nauvoo Temple just after the saints had left, referred to this auditorium as the “grand hall for the assemblage and worship of the people.”[16] As had been the case in Kirtland, there were pulpits at each end of the room representing various offices in the priesthood. Reversible seating again enabled the congregation to face either end of the hall.

The Nauvoo Temple’s exterior had some unique features. These included thirty pilasters containing symbolic ornamental stones. The base of each pilaster was a large stone depicting the crescent moon. Each capital featured the sun’s face. In the cornice above each pilaster was a five-pointed star. Among other things, these stones may have reminded the Saints that there are three degrees of glory, and that faithfully receiving the ordinances of the temple is essential to attaining the highest exaltation in heaven.

As Joseph entered the final months of his life, he exhibited an increasing urgency to make temple blessings available to the Saints. His martyrdom on 27 June 1844 caused only a temporary lull in temple construction. The Saints knew they would soon be forced to leave Nauvoo and lose access to the temple; yet amid preparations for their exodus, the Saints were willing to expend approximately one million dollars to fulfill their Prophet’s plans of erecting the "House of the Lord," where they could receive its sacred blessings.

Specific areas in the temple were completed and dedicated piecemeal so that ordinance work could begin as soon as possible. On 30 November 1845, Brigham Young and twenty others who had received their endowment from Joseph Smith in 1842 gathered to dedicate the attic story for ordinance work. As they had done in the red brick store, they divided the central hall with temporary partitions into separate areas representing distinct stages in man’s eternal progress. The east end had a large gothic window and was furnished with fine carpets and wall hangings. This most beautiful area represented the celestial kingdom. When Joseph Fielding entered this part of the temple for the first time, he felt as though he had truly “gotten out of the World.”[17] Flanking each side of the central hall were six rooms, about fourteen feet square, which served as private offices for Church leaders, as places where priesthood quorums could gather for prayer, or for the initiatory ordinances connected with the endowment. Some of these side rooms contained altars at which sacred sealing ordinances were received.

Endowments were given beginning on 10 December. The number of Saints entering the temple increased as their exodus from Nauvoo drew closer. On 12 January, Brigham Young recorded: “Such has been the anxiety manifested by the saints to receive the ordinances [of the Temple], and such the anxiety on our part to administer to them, that I have given myself up entirely to the work of the Lord in the Temple night and day, not taking more than four hours sleep, upon an average, per day, and going home but once a week.” Others of the Twelve were “in constant attendance,” but had to leave the temple from time to time “to rest and recruit their health.”[18] During the eight weeks prior to the exodus, approximately 5,500 were endowed, fulfilling Joseph Smith’s compelling desire to make these blessings available to the Saints in Nauvoo.

Thus, in contrast to the Kirtland Temple which was a building intended primarily for meetings of the Saints, the Nauvoo Temple was also a place for sacred ordinances, with spaces in the attic and basement devoted to that purpose. This understanding of the two buildings’ different functions may have been reflected in how the Saints normally referred to them. Typically, they called the structure in Kirtland “The Lord’s House,” and the building in Nauvoo a “temple.” All forty references to Kirtland in the Doctrine and Covenants used the word house, while 88 percent of the references to Nauvoo used the word temple. In the History of the Church, 75 percent of the references to Kirtland used the word house, and 93 percent of the references to Nauvoo used the word temple. Even though a dictionary from that time defined temple as “a public edifice erected in honor of some deity” or as “an edifice erected among Christians as a place of public worship,”[19] the Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo appear to have used it in a more specific sense.

Even though the Nauvoo Saints had learned that sacred ordinances were a major purpose of the temple, the concept of it being a multi-function structure lingered. During the hectic time just before and following the exodus, some of the Saints slept, ate, or tended babies in the unused small rooms on the mezzanines above the two main halls. Some people even used the unfinished second-floor auditorium for “dancing and recreation.” [20] Concerned about such irregularities, Elder Heber C. Kimball insisted that only persons with official invitations be admitted to the temple. In this way he was able to restore proper order. This foreshadowed the issuing of recommends to those judged by local Church leaders to be worthy of temple attendance.

Temples in the Tops of the Mountains

After their historic exodus to the Rocky Mountains, the Latter-day Saints continued to build temples. Within days of President Brigham Young’s arrival in the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847, he designated the site for the future temple, and Wilford Woodruff placed a stake in the ground to mark the spot.[21]

On December 23, 1847, an official circular letter from the Twelve invited the Saints to gather and bring precious metals and other materials “for the exaltation . . . of the living and the dead,” for the time had come to build the Lord’s house “upon the tops of the mountains.”[22] This reflected an expanded understanding of temple function. Soon afterward, President Young named Truman O. Angell Sr. as temple architect, a post he would hold until his death in 1887.

Cornerstones for the Salt Lake Temple were laid on 6 April 1853. On this occasion, President Young declared:

I scarcely ever say much about revelations, or visions, but suffice it to say, five years ago last July [1847] I was here, and saw in the Spirit the Temple not ten feet from where we have laid the Chief Corner Stone. I have not inquired what kind of a Temple we should build. Why? Because it was represented before me. I have never looked upon that ground, but the vision of it was there. I see it as plainly as if it was in reality before me. Wait until it is done. I will say, however, that it will have six towers, to begin with, instead of one. Now do not any of you apostatize because it will have six towers, and Joseph only built one. It is easier for us to build sixteen, than it was for him to build one. The time will come when there will be one in the centre of Temples we shall build, and on the top, groves and fish ponds. But we shall not see them here, at present.[23]

William Ward, Truman Angell’s assistant, later recalled how the prophet Brigham shared his vision: “Brigham Young drew upon a slate in the architect’s office a sketch, and said to Truman O. Angell: ‘There will be three towers on the east, representing the President and his two counselors; also three similar towers on the west representing the Presiding Bishop and his two counselors; the towers on the east the Melchisedek priesthood, those on the west the Aaronic priesthood.’”[24]

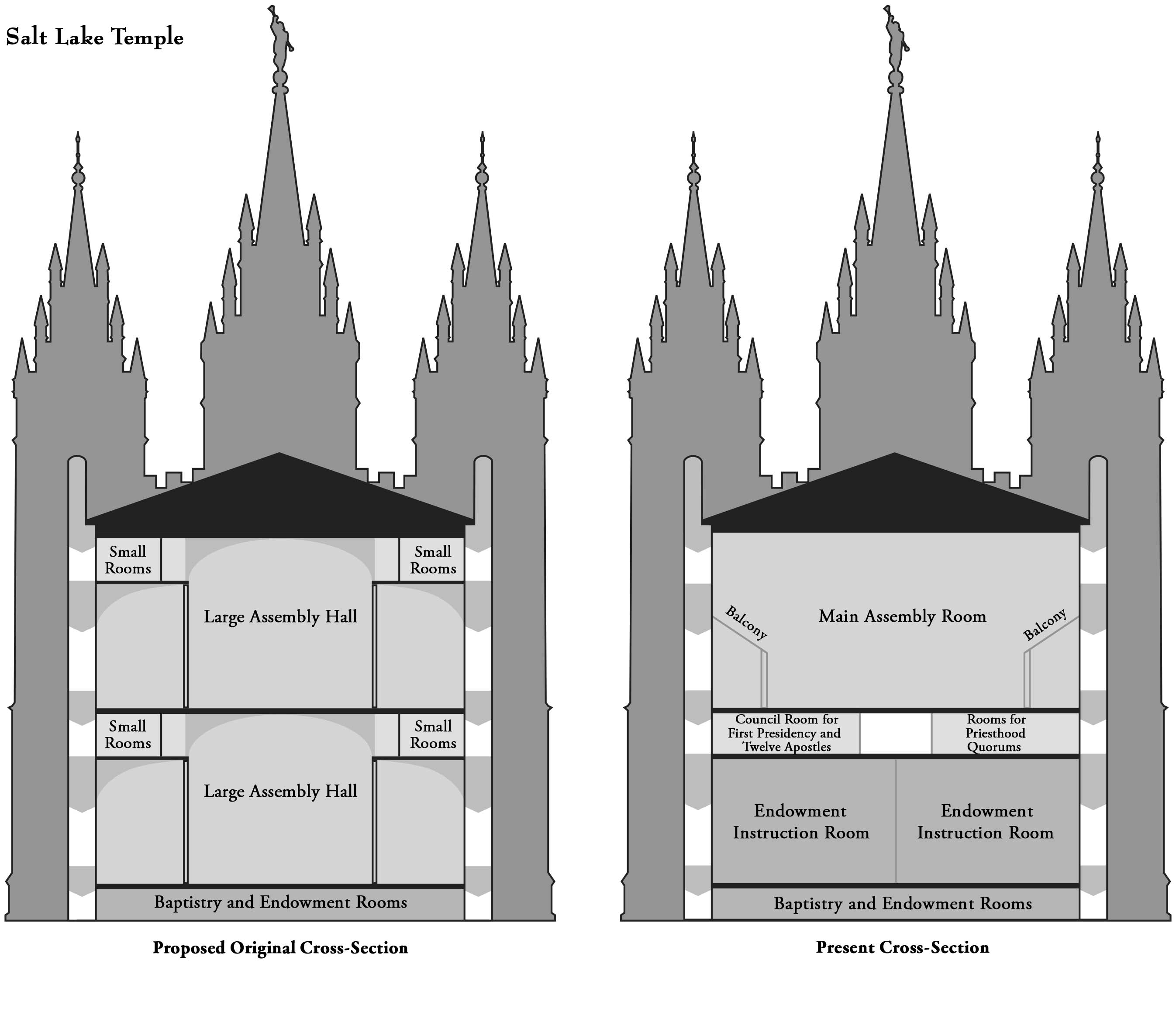

Even though the Saints had learned that performing ordinances was an important temple function, the majority of the space in buildings designed during the pioneer period was still for general meetings. Angell’s original plan called for the Salt Lake Temple’s interior to follow the Kirtland and Nauvoo pattern, having two large halls for general meetings. A font as well as rooms for the endowment and sealings would all be confined to the basement.

Meanwhile, during the pioneers’ early years in the Salt Lake Valley, temple blessings had already been given in various places outside of temples, including the top of Ensign Peak and Brigham Young’s office. By 1852, endowments were being given in the Council House, located on the southwest corner of what are now South Temple and Main Streets. This facility also accommodated a variety of other ecclesiastical and civic functions, so a separate place was needed where the sacred temple ordinances could be given in a more secluded setting. The Endowment House, a two-story adobe structure dedicated in 1855 to serve as a temporary facility while the Salt Lake Temple was being completed, was located in the northwest corner of Temple Square. It was the first building to be designed exclusively for sacred ordinances and to have separate permanent rooms with murals painted on the walls to represent the different stages of man’s progression back to God as discussed in the temple endowment.

As had been the case with Joseph Smith, Brigham Young demonstrated during the final years of his life a heightened drive to reemphasize temple service. In the St. George Temple, dedicated just a few months before President Young’s death in 1877, members performed the first vicarious ordinations, endowments, and sealings of children to parents for the dead. Thus, Elder Hafen has suggested that the restoration of temple service was completed in three stages: Kirtland, Nauvoo, and St. George.[25]

Although temple functions were changing, Brigham Young and the architects were reluctant to deviate from the design established by Joseph Smith. Therefore, the St. George Temple, built during the 1870s, still followed closely the pattern of the Nauvoo Temple with two large meetings halls. When it opened, the plan was to conduct all ordinances except sealings in the basement. Thus, this arrangement did not follow the pattern of the Endowment House, but was similar to that proposed a quarter of a century earlier for the Salt Lake Temple. Areas for the endowment were partitioned by temporary painted dividers called screens. Within a few weeks, however, temple leaders realized that the “ordinance rooms in the basement were not of sufficient size to accommodate the crowds that continued flocking to the temple.” After “much discussion,” they “determined to make greater use of the lower main assembly room [immediately] above the basement.” At first, this entire hall represented the terrestrial kingdom, and the tower room behind the Melchizedek Priesthood pulpits represented the celestial. Soon afterwards, however, portions of the large hall were set off by screens to form the terrestrial and celestial rooms, rooms in the tower being used for sealings.

As endowments for the dead quickly became the activity occupying the most time in the temple, Church leaders felt the need to have facilities that would more adequately accommodate this function. That there would be variations in temple design had been made known to President Brigham Young in St. George. “Oh Lord,” he had prayed, “show unto thy servants if we shall build all temples after the same pattern.” “Men do not build their homes the same when their families are large as when they are small,” came the inspired response. “So shall the growth of the knowledge of the principles of the gospel among my people cause diversity in the pattern of temples.”[26] Years earlier, at the time ground was broken for the Salt Lake Temple, President Young had taught that the order of priesthood ordinances is made known by revelation, and therefore we should know what facilities must be included in our temples.[27]

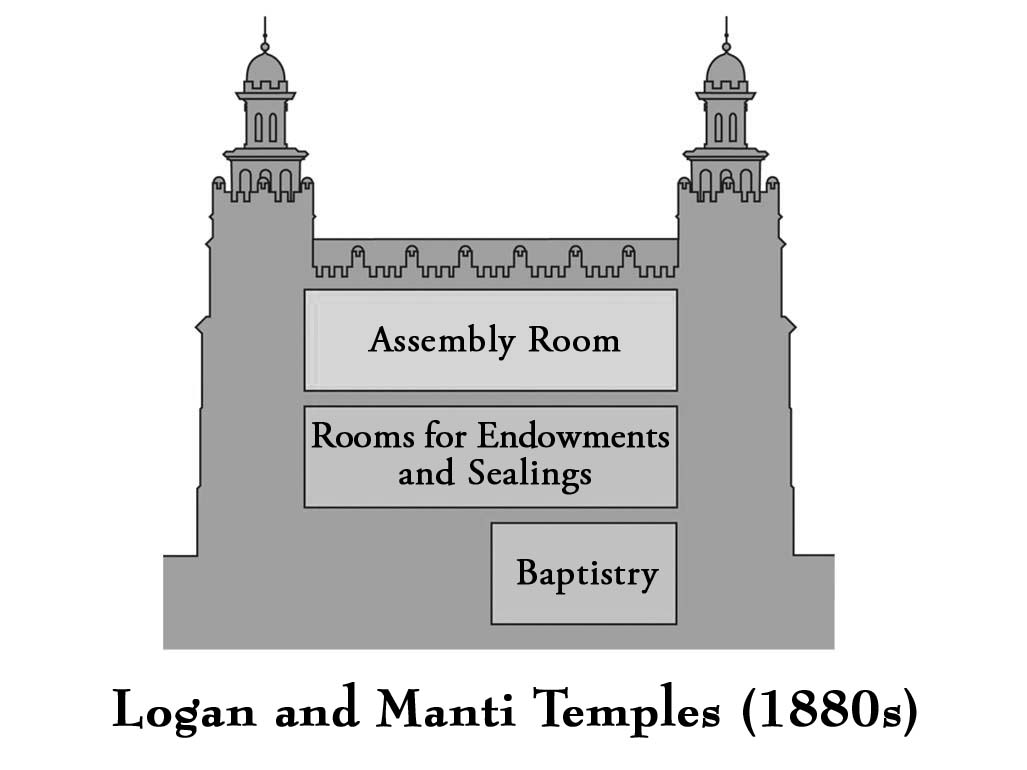

The pattern of separate ordinance rooms for the endowment, first seen in the Endowment House, would be reflected more fully in the Manti and Logan Temples. Architectural historian Paul Anderson believed that the basic designs for these two temples was “probably worked out in Salt Lake City under the supervision of Brigham Young.”[28] Both buildings would have two towers. The lower half of each temple was divided into specific rooms designed for presenting temple ordinances more effectively; only the upper of the two former Assembly Halls remained as space for general meetings. Hence these buildings represented a shift in designing temples to better serve their unique ordinance function, expanding this area from just the basement to the entire lower half of the structure.

The Salt Lake Temple’s exterior walls were nearing completion in the mid-1880s when Church leaders considered changing the interior plan to match the concept adopted for Manti and Logan. Truman O. Angell Jr., who was assisting his elderly father in completing drawings for the Salt Lake Temple, pointed out that having specific rooms for the endowment would accommodate three hundred persons in a session—more than twice the number that could be served in the basement under the original arrangement. These changes were consistent with President Young’s 1860 instructions that the temple would not be designed for general meetings, but rather it would “be for the endowments—for the organization and instruction of the Priesthood.”[29]

While the focus has shifted from general meetings to performing ordinances, temples still fulfilled their first traditional function—being a place of revelation between God and man. An outstanding example was the Savior’s appearance to President Snow in the large corridor just outside the celestial room of the Salt Lake Temple. President Snow later described what happened: “It was right here that the Lord Jesus Christ appeared to me at the time of the death of President Woodruff. He instructed me to go right ahead and reorganize the First Presidency of the Church at once and not wait as had been done after the death of the previous presidents, and that I was to succeed President Woodruff. . . . He stood right here, about three feet above the floor. It looked as though He stood on a plate of solid gold.”[30]

Because of its location near Church headquarters, the Salt Lake Temple also plays a unique and significant role in Church governance. An intermediate floor was added to this temple’s design, with special rooms for the use of the General Authorities. Key decisions are made following prayerful consideration by the Council of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who meet weekly in their council room on this floor. These decisions include such matters as ordaining and setting apart new presidents of the Church, appointing other General Authorities, creating new missions and stakes, and approving Church programs. Notable examples have included the 1952 decision to build temples overseas, the determination in 1976 to add sections 137 and 138 to the Doctrine and Covenants, and the 1978 revelation extending the priesthood to all worthy males (D&C: Official Declaration 2).

More Recent Temples

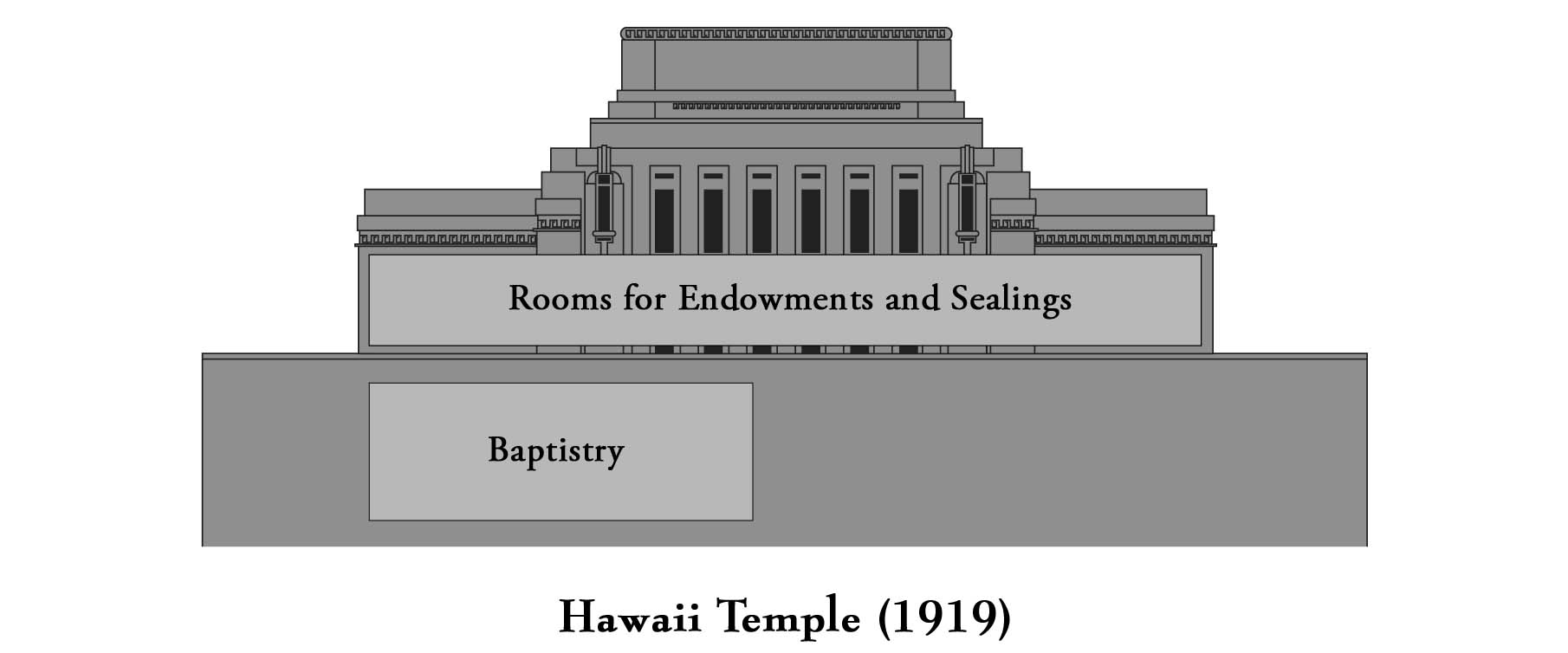

In the early twentieth century, the remaining plans for a large upper meeting hall were also omitted beginning with the Hawaii Temple dedicated in 1919. Hence, temples had completed the transition from a multipurpose structure designed primarily for general meetings, as at Kirtland, to buildings designed exclusively for sacred ordinances. Since that time, only the Los Angeles and Washington D.C. Temples, the second and third largest in the Church, would include the large upper solemn assembly hall.

Since the midpoint of the twentieth century, Church leaders have approved changes which have enabled temples to perform their ordinance function more efficiently. Beginning with the Swiss Temple, dedicated in 1955, films have facilitated the presentation of the endowment in diverse languages and in a smaller space. Increasing the number of presentation rooms to six at the Ogden and Provo Temples, dedicated in 1972, enabled endowment sessions to begin every twenty minutes. In 1997, at the Mormon colonies in northern Mexico, President Gordon B. Hinckley was inspired to formulate a plan for accommodating all temple functions in much smaller structures, making temple blessings increasingly available even to Saints in remote areas of the world.

Thus, the design of more than 150 temples stands as a tangible reminder of how temple service was restored line upon line. Because the recent spread of temples worldwide has made their sacred blessings accessible to an ever-growing number of Church members, the challenge for Latter-day Saints is to show their appreciation by entering these sacred houses, enriching their own lives, and making temple ordinances available to their kindred dead.

Notes

[1] James E. Talmage, The House of the Lord (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962), 110–11.

[2] Joseph Smith History vol. A-1, 300, Church History Library.

[3] Orlen C. Peterson, “A History of the Schools and Educational Programs of the Church . . . in Ohio and Missouri, 1831–1839” (master’s thesis, BYU, 1972), 23–24.

[4] David J. Howlett, Kirtland Temple: The Biography of a Shared Mormon Sacred Space (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014), 17.

[5] Marvin E. Smith, “The Builder,” Improvement Era, October 1942, 630.

[6] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 6 April 1853 (Liverpool: Franklin D Richards, 1855), 2:31, emphasis in original.

[7] Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 9 April 1871, 14:273.

[8] In the light of new information discovered in connection with the Joseph Smith Papers Project, the date of this revelation has been changed to August 2, 1833, beginning with the 2013 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.

[9] For a more complete discussion of the Kirtland Temple’s pulpits and their relationship to the 24 temples in Zion, see Richard O. Cowan, “The House of the Lord in Kirtland: A Preliminary Temple,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Ohio (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1990), 112–18.

[10] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 1 January 1877, 18:303.

[11] Harold B. Lee, “Correlation and Priesthood Genealogy,” address at Priesthood Genealogical Research Seminar, 1968 (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 1969), 60, quoted in Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1989), 33.

[12] Obituary for Seymour Brunson, Times and Seasons, September 1940: I:176

[13] For a discussion of this topic, see Michael W. Homer, Joseph’s Temples: The Dynamic Relationship between Free Masonry and Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2014).

[14] Joseph Smith, History, 1838-1856, vol. C-I, Church History Library.

[15] Joseph Smith, History, 1838-1856, vol. E-1, Church History Library; emphasis in original.

[16] Quoted in E. Cecil McGavin, The Nauvoo Temple (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1962), 92.

[17] Andrew F. Ehat, ed., “‘They Might Have Known That He Was Not a Fallen Prophet’—The Nauvoo Journal of Joseph Fielding,” BYU Studies 19, no. 2 (Winter 1979): 158–59.

[18] Smith,History of the Church, 7:567.

[19] Noah Webster’s First Edition of an American Dictionary of the English Language, facsimile Edition (San Francisco: Foundation for American Christian Education, 1967), s v. “temple.”

[20] Stanley B. Kimball, Heber C. Kimball: Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 117.

[21] Matthias F. Cowley, Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1964), 619–20; History of the Church, 3:279—80. After reviewing various diary entries, Randall Dixon believes that this event took place on 26 July 1847 (statement to the author, 6 May 2010).

[22] James R. Clark, comp., Messages of the First Presidency (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 1:333.

[23] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 1:133.

[24] “Who Designed the Temple?” Deseret Weekly, 15 April 1892, 578.

[25] See Bruce C. Hafen, Book Review of Blaine M. Yorgason, Richard A. Schmutz, and Douglas D. Alder. All That Was Promised: The St. George Temple and the Unfolding of the Restoration, BYU Studies 54, no. 3 (2015): 193.

[26] Erastus Snow, 20 November 1881, in St. George Stake Historical Record, Church History Library.

[27] Brigham Young, 14 February 1853, in Journal of Discourses, 1:277–78.

[28] Paul L. Anderson, “William Harrison Folsom: Pioneer Architect,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (Summer 1975): 253.

[29] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 8:203.

[30] LeRoi C. Snow, “An Experience of My Father’s,” Improvement Era, September 1933, 677, 679.