Hyrum Smith's Liberty Jail Letters

Kenneth L. Alford and Craig K. Manscill

Kenneth L. Alford and Craig K. Manscill, "Hyrum Smith's Liberty Jail Letters," in Foundations of the Restoration: The 45th Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, ed. Craig James Ostler, Michael Hubbard MacKay, and Barbara Morgan Gardner (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 189-206.

Kenneth L. Alford was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published. Craig K. Manscill was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

The story of Liberty Jail has frequently been told from the perspective of Joseph Smith, but the experience of Hyrum Smith has largely been ignored. Hyrum wrote and received several letters while in Liberty Jail, and his letters provide valuable information about conditions and events during the imprisonment, give context to events in the Church at large, and add insights into the struggles his family endured during the Missouri persecutions and as refugees in Illinois. A close study of Hyrum’s letters provides insights into the development, writing, and doctrines espoused in Doctrine and Covenants 121, 122, and 123.

Prelude to Liberty Jail

Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Parley P. Pratt, and other leaders were betrayed at Far West into the hands of Major General Samuel D. Lucas and the Missouri militia on 31 October 1838.[1] Hyrum Smith and Amasa Lyman were captured later that day while attempting to flee to Iowa.[2] In Richmond, Missouri, on 29 November 1838, Austin A. King, a fifth judicial circuit judge, signed the court order charging six prisoners with “treason against the state of Missouri.”[3] The six men were Joseph Smith, who would turn thirty-four years old in three weeks; Sidney Rigdon, forty-five; Hyrum Smith, thirty-eight; Alexander McRae, thirty-one, the youngest member of the group; Lyman Wight, forty-two; and Caleb Baldwin, forty-seven, who was the oldest.

Hyrum later testified that he heard the judge say “that there was no law for us, nor for the Mormons, in the state of Missouri; that he had sworn to see them exterminated, and to see the Governor’s order executed to the very letter, and that he would do so.”[4] The detainees were bound over to Sheriff Samuel Hadley for transport to Liberty Jail. Prior to being taken to jail, they were handcuffed and chained together. During the course of his work, the blacksmith informed the prisoners that “the judge [had] stated his intention to keep us in jail until all the Mormons were driven out of the state.”[5] With the exception of Sidney Rigdon, who was freed on 5 February 1839, the detainees would be incarcerated the entire winter—from 1 December 1838 until 6 April 1839—in the unheated jail.[6]

Isolated from Church headquarters, the jailed Church leadership was rendered unable to lead the Church out of Missouri. Communication with the outside world was limited to letters and visitors. As Liberty is forty miles from Far West, it was possible for family, friends, and Church leaders to call on the prisoners. All of the men except Hyrum received visits from their wives during December.[7] They were visited in January over twenty times, with all of the wives visiting at least once. During one of those visits, Hyrum blessed his newborn son, Joseph Fielding Smith.[8] Jail visitors decreased during February and March as an increasing number of Church and family members fled Missouri for the safety of Illinois.

Hyrum later commented, “We endeavored to find out for what cause [we were to be thrust into jail], but all that we could learn was [that it was] because we were Mormons.”[9] Life in the jail was difficult; Hyrum further reported that “poison was administered to us three or four times, the effect it had upon our systems was, that it vomitted us almost to death, and then we would lay in a torpid stupid state, not even caring or wishing for life.” He also said, “We were also subjected to the necessity of eating human flesh for the space of 5 days or go without food, except a little coffee or a little corn bread—the latter I chose in preference to the former. We none of us partook of the flesh except Lyman Wight.”[10]

Bishop Partridge’s 5 March Letter

On 5 March, Bishop Edward Partridge wrote a letter from Quincy, Illinois, to the “Beloved Brethren” in Liberty Jail providing details of the Church in Illinois. Partridge explained that he wrote because of “an opportunity to send direct to you by br[other] Rogers.”[11] In addition to Partridge’s letter, David Rogers also carried a 6 March letter from Don Carlos and William Smith, two of Joseph and Hyrum’s brothers, and a 7 March letter from Emma, Joseph’s wife.[12] Rogers left Quincy on 10 March 1839 and delivered the letters on 19 March.[13]

Liberty Jail Correspondence

In the difficult conditions of Liberty Jail, the prisoners faced several challenges when it came to writing and receiving letters. The first problem, as Hyrum mentioned in his 19 March letter to his wife Mary was that they were often in need of paper and ink. The second was difficulty receiving letters. And third was the challenge of finding trustworthy people to deliver their letters. As an increasing number of Church members fled Missouri, letters became the only viable means of communication with family members and Church leaders now in Illinois.

We are currently aware of eight letters Hyrum Smith wrote from Liberty Jail (see tables 1 and 2). Seven of them are dated and were penned during March and April 1839. At least four of the letters, and possibly five, were written prior to Joseph’s 20 March letter of instruction, portions of which would be canonized as D&C 121–123. Hyrum’s first two letters, both dated 16 March, were written to Hannah Grinnals and his wife Mary Fielding Smith. Hannah was a longtime, trusted friend, who lived with Hyrum and Mary for almost twenty years. She first appears in the historical record in 1837 giving aid to Hyrum’s family when his daughter Sarah was born and his first wife, Jerusha, died while he was away on Church business. Hannah likewise assisted Mary with Joseph F. Smith’s birth on 13 November 1838, almost two weeks after Hyrum had been arrested.[14] When Hyrum wrote to Hannah from Liberty Jail, he thanked her for “friends[h]ip you have manifested towords my family I feel grateful to you for your Kindness.” He included words of encouragement and counsel to his daughter Lovina and to Clarinda, who was likely Hannah’s daughter, as well as general counsel to his other children “little John little Hiram little Jerusha & little Sarah” that they “must be good little children till farther [sic] comes home.” He also confided to Hannah, “I want you should stay with the family and nev[e]r leave them My home shall be your home for I shall have a home though I have none now . . . my house shall be your home.”[15]

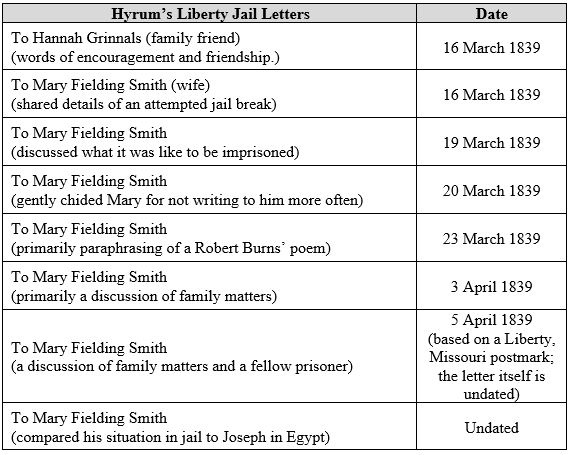

Table 1. Hyrum Smith’s Liberty Jail Letters.

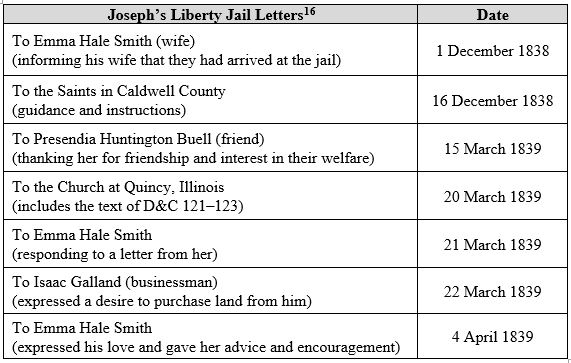

Table 2. Joseph Smith’s Liberty Jail Letters.

Hyrum’s six remaining letters were written to Mary. While we can date five of those letters (19 March, 20 March, 23 March, 3 April, and 5 April), the sixth remains undated because the first page is missing.[17] Hyrum addressed the undated letter to Mary at Quincy, Illinois, which provides some clue as to the approximate date it was written. Joseph and Hyrum’s families left Far West on 7 February. We are uncertain when they reached Illinois, but we know that they settled in Quincy, Illinois, prior to 5 March 1839. In his 5 March letter to the Liberty Jail inmates, Bishop Edward Partridge informed Joseph and Hyrum that “Brother Joseph’s wife lives at Judge [John] Cleveland[’]s, I have not seen her but I sent her word of this opportunity to send to you. Br[other] Hyrum’s wife lives not far from me.” Bishop Partridge added, “I have been to see her a number of times, her health was very poor,” implying that Mary Fielding Smith had arrived in Quincy well before 5 March.[18]

In a 6 March letter to Hyrum and Joseph written from Quincy, their younger brother Don Carlos explained, “Father’s family have all arrived in this state except you two. . . . Emma and Children are well, they live three miles from here, and have a tolerable good place. Hyrum’s children and mother Grinolds[19] are living at present with father; they are all well, Mary [Fielding Smith] has not got her health yet, but I think it increases slowly. She lives in the house with old Father Dixon, likewise Br[other] [Robert B.] Thompson and family; they are probably a half mile from Father’s.”[20] Based on the short time Joseph and Hyrum remained incarcerated after Joseph’s 20 March letter (they left the jail, never to return, on 6 April), there is a greater possibility that the undated letter from Hyrum to Mary was written prior to Joseph’s 20 March letter of counsel and instruction rather than on some later date.

Joseph’s 20 March 1839 Letter

In a long letter dated 20 March, Joseph wrote “To the church of the Latterday saints at Quincy Illinois and scattered abroad and to Bishop [Edward] Partridge in particular.” The letter consists of two lengthy parts. Both parts have been assigned a 20 March 1839 date by historians.[21] The first seventeen pages, labeled by the Joseph Smith Papers project as 20 March 1839–A, include text that would eventually be canonized as D&C 121:1–33. The 20 March[22] letter is signed by the five men who remained in Liberty Jail—Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Lyman Wight, Caleb Baldwin, and Alexander McRae.[23] The letter was recorded “by Alexander McRae and Caleb Baldwin, who acted as scribes for Joseph Smith.”[24] Historian Stephen C. Harper concluded that “frequent misplaced and misspelled words show the rush in which the dictation was scribbled down.”[25] Inspection of the original pages shows that Joseph made a few corrections to the text.

The second part of that letter, identified in the Joseph Smith Papers as 20 March 1839–B, is an additional nine handwritten pages. Those pages begin with the heading “Continued to the church of Latter-day-saints” and are signed by the same five detainees. One of the purposes of the additional pages was “to offer further reflections to Bishop [Edward] Partridge and to the church of Jesus Christ of Latter day saints whom we love with a fervent love.”[26] It is certainly possible that both parts of the letter had been composed in a single sitting or on a single day, but it seems somewhat irregular that the authors would sign their names twice to the same letter. It is from the second part that D&C 121:34–46, D&C 122, and D&C 123 were later excerpted and added to the Doctrine and Covenants.

Joseph addressed a cover letter, written on 21 March 1839 to his “Affectionate Wife” Emma. Joseph explained that he sent “an Epistle to the church directed to you because I wanted you to have the first reading of it and then I want Father and Mother to have a coppy of it keep the original yourself as I dectated the matter myself.” At the end of his three-page cover letter, Joseph touchingly asked his wife: “My Dear Emma do you think that my being cast into prison by the mob renders me less worthy of your friendsship” and then he provided the answer he hoped to receive: “No I do not think so.”[27]

Lyman Wight’s journal states that “Brother Ripley [almost certainly Alanson Ripley, a participant in Zion’s Camp who served on a committee to remove poor members of the Church from Missouri] came in and took our package of letters for Quincy” on 22 March—possibly providing sufficient time and opportunity for the second part of Joseph’s letter to have been dictated and signed on 21 March along with Joseph’s cover letter to Emma.[28]

Hyrum’s Relationship with Joseph’s 20 March Letter

The letter dictated by Joseph Smith on 20 March (and possibly 21 March) contains “some of the most sublime revelations ever received by any prophet in any dispensation.”[29] It is reasonable to consider that many of the thoughts, feelings, doctrines, counsel, and teachings found throughout the letter—in both the canonized and noncanonized sections—had been germinating for many weeks prior to being recorded. With so little to occupy their time in jail, Joseph and his fellow prisoners had many days to reflect upon the content expressed in that letter. That would be especially true for conversations Joseph had with his beloved brother Hyrum. The overlapping content in Joseph’s and Hyrum’s letters demonstrate that they included some of that conversation in their letters. Hyrum’s letters demonstrate that some of the ideas in D&C 121–123 took shape orally before they were committed to paper.

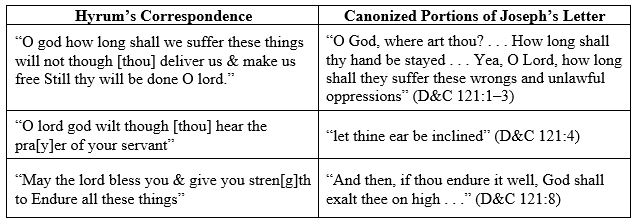

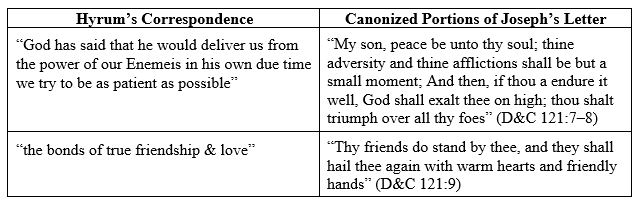

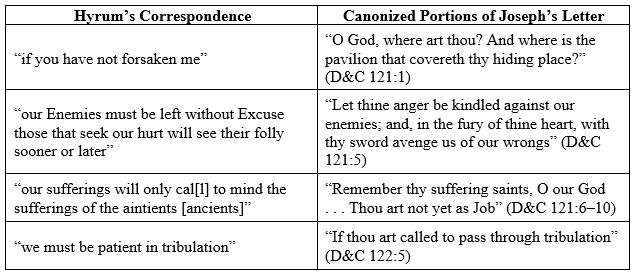

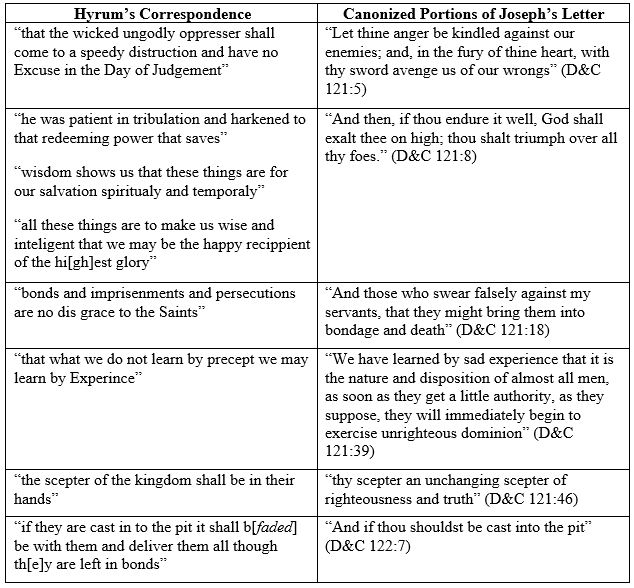

Excerpts from Hyrum’s letters are included in tables 3–7. Text in the left-hand columns is from Hyrum’s Liberty Jail diary and letters. The right-hand columns list similarly themed excerpts from D&C 121, 122, and 123. We will leave it to the reader to draw conclusions as to whether or not the presumed interchange of ideas between brothers can be seen within Hyrum’s letters and diary entries.

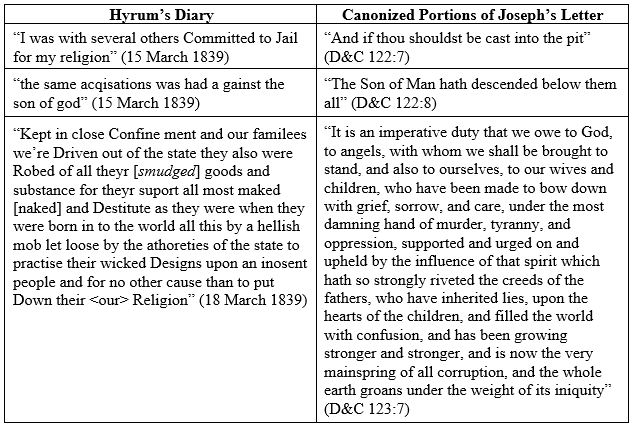

Diary entries: Hyrum Smith kept a contemporary diary while incarcerated in Liberty Jail. The three excerpts below are entries from Hyrum’s diary dated 15 March and 18 March, which share similar sentiments to verses found in Doctrine and Covenants 122 and 123.

Table 3. Excerpts from Hyrum Smith’s diary, March 1839

Hyrum’s 16 March letter to Mary Fielding Smith. In this letter, addressed to “Mary, my dear Companion,” Hyrum shared details regarding an attempted jail break. As he explained:

Some friend put some auguers [augers] in to the window & an iron bar we made a hole in through the logs in the lower room & through the stone wall all but the out side stone which was suffitiently large to pass out when it was pushed out but we were hind[e]red for want of handles to the auguers the logs were so hard that the handles would split & we had to make new ones with our fire wood we had to bore the hole for the shank with my penknife which delayed time in Spite of <all> we could do the day of Examination came on before in the after noon. that Evening we was ready to make our Essape [escape] & we were discovered & prevented of making our Essape there apeared to be no hard feelings on the part of the Sheriff & Jailor but the old Baptists & prisbiterians & Me[t]hodests were very mutch Excited they turned out in tens as volenteers to gard the Jail till the Jail was mended.[30]

Hyrum closed this letter with the following plea: “O god in the name of thy son preserve the life & health of my bosom companeon & may she be prsious [precious] in thy sight & all the little children & that is pertaining to my family & hasten the time when we shall meet in Each others Embrass [Embrace].” The following statements in this letter sound similar to text included in Doctrine and Covenants 121–123:

Table 4. Excerpts from Hyrum Smith’s 16 March 1839 letter to Mary Fielding Smith

Hyrum’s 19 March letter to Mary Fielding Smith. From this letter we learn that Hyrum was ill—“q[u]ite out of hea[l]th to day have Kept my bed all day”—the day before Joseph dictated his 20 March letter. He expressed his disappointment “that I did not hear from you & the family by your own pen” and let her know that “brother Pa[r]tr[i]dge says he imformed you of the oppertunity of sending [a letter] by brother Rodgers.” He conceded that “I do not Know but your was sick so that you could not write.” Hyrum shared that he was “verry anxious to hear from you,” and he worried about his family. “I have been informed,” he wrote, “that you are sepperated from the family . . . on this side of the river & you on the other . . . my feelings & anxiety is sutch that my sleep has departed from me.” And then Hyrum confided that his jail experience was wearing on him: “My faith understanding & Judgement is not suffitient to over come these feelings of sorrow a word from you might possibly be sattisfactory or in degree relieve my feelings of anxiety that sleep may return.” He also provided a glimpse into the physical toll life in jail exacted. “Excuse my poor writing my nerves are some what affected & <my hands> are this Evening q[u]ite swolen & fingers are stiff & painfull with the rheum[a]tism.”[31] Two statements from this letter sound similar to the canonized portions of Joseph’s 20 March letter:

Table 5. Excerpts from Hyrum Smith’s 19 March 1839 letter to Mary Fielding Smith

Hyrum’s 20 March letter to Mary Fielding Smith. Hyrum informed Mary that David Rogers visited that morning and that Alanson Ripley was also there and “is a going to start back to [faded] this after noon.” Ripley did not depart on 20 March, though, because Joseph’s cover letter to Emma, which he carried to Illinois, is dated on the following day. Toward the end of this letter, Hyrum again gently chided Mary for not writing: “I thought if you could not write you could send a friendly word, . . . I do not wish to harrow up your feelings if they are inocent but I thought it strange that you did not send one word to me when I thought you Knew I was so anxious to hear from you. . . . If you have no feelings for me as a husband you could sent or caused to be sent some information concerning the little babe or those little children that lies near my hart.” Unlike the other letters to Mary, this letter has no signature or address.[32] As this letter is dated the same day as Joseph’s letter, it is no surprise that several concepts from the latter found their way into the former.

Table 6. Excerpts from Hyrum Smith’s 20 March 1839 letter to Mary Fielding Smith

Hyrum’s undated (presumably pre-20 March) letter to Mary Fielding Smith. This letter is addressed (on the final page) to “Mrs Mary Smith, Q[u]incy Adams Co Ilinois.” In the extant pages, Hyrum compares the prisoner’s situation to Joseph in Egypt who “was sold by his bretheren notwithstanding he was cast in to prison for many years yet the power of wisdom was there all though men thought to disgrace him but they fail’d.” He shared his opinion with Mary that “bonds and imprisenments and persecutions are no dis grace to the Saints it is that is common in all ages of the world since the days of adam for he was persecuted by his own posterity in the days of Seth with sutch violence the he had to flee out of his own count[r]y to an other land.” He closed this letter by asking Mary to “pray for me my companion I will pray for <you> unceasingly as mutch as I can.” After signing his name, he asked Mary to “Excuse all imperfections.”[33]

Table 7. Excerpts from an undated letter from Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith

As these letter excerpts demonstrate, Hyrum Smith appears to have been involved in discussions regarding the doctrines and concepts included in Joseph’s 20 March letter. For a brief time, that letter of instruction served almost as a de facto Church presidency while the Church was deprived of Joseph and Hyrum’s presence. It should not come as a surprise that Joseph and Hyrum discussed much of the contents of Joseph’s 20 March letter; they were experiencing the same trying conditions, emotions, and family difficulties. Plus, there was a strong and lifelong bond between them.

There are additional similarities to Joseph’s 20 March letter in Hyrum’s subsequent letters and diary entries, but they do not necessarily reflect discussions that could have occurred between Joseph and Hyrum prior to Joseph dictating the 20 March letter.

Release from Liberty Jail

The five prisoners left Liberty Jail on 6 April and were taken to Daviess County to appear before Judge Birch. For ten days a ribald and irreverent grand jury boasted of abuses they had perpetrated on the Mormons. Hyrum reported that after ten days of the grand jury’s drunken antics, “we were indicted for treason, murder, arson, larceny, theft, and stealing.”[34] The prisoners requested a change of venue to Marion County, but were granted instead a change to Boone County. “They fitted us out with a two horse wagon, and horses, and four men, besides the sheriff, to be our guard,” according to Hyrum. “There were five of us [prisoners]. We started from Gallatin the sun about two hours high, P.M., and went as far as Diahman that evening and staid till morning. There we bought two horses of the guard, and paid for one of them in our clothing, which we had with us; and for the other we gave our note.” Upon reaching Boone County, “we bought a jug of whiskey; with which we treated the company.” The sheriff informed the prisoners that Judge Birch had instructed him “never to carry us to Boon[e] county . . . and said he, I shall take a good drink of grog and go to bed, and you may do as you have a mind to. Three others of the guard drank pretty freely of whiskey, sweetened with honey; they also went to bed, and were soon asleep, and the other guard went along with us, and helped to saddle the horses.”[35]

Joseph and Hyrum mounted the horses, and Caleb Baldwin, Lyman Wight, and Alexander McRae started walking to Quincy, Illinois. Joseph and Hyrum reached Quincy on 22 April 1839 where they found their families “in a state of poverty, although in good health.”[36] Their extended ordeal had reached an end.

Aftermath

Joseph’s 20 March letter was considered a historical document and was not canonized during Joseph and Hyrum’s lifetime. Both parts of the 20 March 1839 letter were published several times prior to Doctrine and Covenants 121–123 being canonized, including excerpts printed in the Times and Seasons, the Deseret News, and the British Millennial Star.[37] Sometime prior to 15 January 1875, Elder Orson Pratt received an assignment from Brigham Young to work on a new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants “arranging the order in which the revelations are to be inserted.” Elder Pratt “divided the various revelations into verses, and arranged them for printing, according to the order of date in which they were revealed.”[38] Responsibility regarding which excerpts from the 20 March letter would be canonized was also apparently left to Elder Pratt. The seven excerpts (five which were stitched together to become Doctrine and Covenants 121 with one contiguous excerpt providing the text for sections 122 and 123) were included in the 1876 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. The Pearl of Great Price was sustained as one of the four standard works of the Church during the October 1880 general conference; Doctrine and Covenants 121, 122, and 123 were canonized at the same time.[39]

Notes

[1] It is insightful to note that both Lilburn W. Boggs and Samuel D. Lucas were residents of Jackson County, Missouri, and had figured prominently in the 1833 expulsion of the Saints. In 1833, Boggs was Missouri’s lieutenant governor and Lucas was a county court justice and colonel of local militia. See Leland H. Gentry and Todd M. Compton, Fire and Sword: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Northern Missouri, 1836–39 (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 15.

[2] Church Educational System, Church History in the Fulness of Times Student Manual: Religion 341 through 343 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2003), 205.

[3] Judge King had determined the outcome before the hearing. “If a Cohort of angels were to come down and declare we were clear Donaphan said it would all be the same for he King had determined from the begining to Cast us into prison.” Sidney Rigdon, Joseph Smith, et al., Petition Draft (“To the Publick”), circa 1838–1839, 45b, http://

[4] Statement of Hyrum Smith, July 1, 1843, History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], 1615, http://

[5] History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], 1615, http://

[6] Clark V. Johnson, ed., Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1992), 680–81. On 1 July 1843, Sidney Rigdon testified before the Municipal Court of Nauvoo that in January 1839, “I was ordered to be discharged from prison, and the rest remanded back. . . . It was some ten days after this before I dared leave the jail. . . . Just at dark, the sheriff and jailer came to the jail with our supper. . . . I whispered to the jailer to blow out all the candles but one, and step away from the door with that one. All this was done. The sheriff then took me by the arm, and an apparent scuffle ensued. . . . We reached the door, which was quickly opened, and we both reached the street. He took me by the hand and bade me farewell, telling me to make my escape, which I did with all possible speed.” See also History, 1838–1856, volume E-1 [1 July 1843–30 April 1844], http://

[7] History of the Reorganized Church, 2:309. Mary Fielding Smith had recently given birth to a son, Joseph F. Smith on November 13, 1838, and her health remained poor for many weeks.

[8] History of the Reorganized Church, 2:315.

[9]“Statement of Hyrum Smith, July 1, 1843,” History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], 1615, http://

[10] Hyrum Smith, quoted in Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, 273, http://

[11] Letter from Edward Partridge, 5 March 1839, http://

[12] Letter from Don Carlos Smith and William Smith, 6 March 1839. Letter from Emma Smith, 7 March 1839, http://

[13] Elder David White Rogers, Journal History, 17March 1839. Salt Lake City: Church History Library, 2-4. The typewritten copy of Rogers’s statement that appears in the Journal History is dated February 1, 1839 at Quincy, Illinois. The date is somewhat problematic because the majority of the statement outlines events that occurred well after February 1, 1839. It seems likely that Rogers began his statement, which details his efforts with S. Bent and Israel Barlow to find a suitable location for the Saints to settle in Illinois, on February 1 and simply did not re-date the completed statement. Rogers recorded: “We left Far West on the 20th. I have visited the brethren in Richmond Jail in the meantime. And on the morrow [21 March] we visited the Prophet Joseph Smith in Liberty Jail.” There appears to be a dating error in Rogers’ account, though because both Hyrum and Joseph wrote that they received Bishop Partridge’s letter on 19 March—not 21 March as Rogers remembered. In a letter to his wife Mary, dated 19 March, Hyrum wrote that “we receaved a letter this evening from brother [Edward] Pa[r]tridge by the hand of brother Rodgers it was q[u]ite late when it came to us & we was out of paper except this scrap & the mesinger said he should start very Erley in the morning.” Holograph, Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 19 March 1839, MS 2779, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. In his 20 March letter (a few lines prior to the location where the text for D&C 121:7–25 would later be extracted), Joseph stated that “we received some letters last evening one from Emma one from Don C. Smith and one from Bishop Partridge all breathing a kind and consoling spirit”— showing that Rogers arrived at the jail on 19 March. (Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Letter to the Church and Edward Partridge, 20 March 1839–A: http://

[14] Lucy Mack Smith referred to Hannah as “Mrs. Grenolds.” The spelling “Grinnals” is from the Nauvoo Temple Endowment Register, which records her endowment on 31 December 1845 and gives her date of birth as 3 November 1783. The Hannah Grennell (born 3 November 1796, Killingsworth, Connecticut) found in the Church’s patriarchal blessing index may be the same person despite the discrepancy in the year of birth. The blessing, given in Nauvoo on 4 July 1845, records her parents as William Woodstock and Elizabeth with no last name given. The patriarchal blessing indicates that Hannah would receive her companion and children in the resurrection of the just, suggesting that she may have been a widowed mother of more than one child. The 1850 federal census lists a sixty-six-year-old Hannah Grennells, born in Connecticut, as a member of Mary Smith’s home. This is consistent with the 1840 federal census (from Hancock County, Illinois), which lists a woman between fifty and sixty years of age living in Hyrum’s home. If the girl listed with Hannah in the 1840 census is her daughter Clarinda then she and Hyrum’s daughter Lovina were near the same age. According to historian Don C. Corbett, Hannah “died two years after Mary Smith, who passed away on 21 September 1852 at the age of fifty-eight.” If Hannah died in 1854, however, she would have been seventy according to the 1850 federal census. Mary Fielding Smith’s obituary appeared in the 11 December 1852, Deseret News; if Hannah had a published obituary it is yet to be located. Considering Hannah’s long-term relationship and significant contributions to Hyrum’s family, there is an amazing paucity of information about her. See Don Cecil Corbett, Mary Fielding Smith: Daughter of Britain (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970); Pearson H. Corbett, Hyrum Smith, Patriarch (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976); and Orson F. Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1978).

[15] Hyrum Smith to Sister Grinnals, 16 March 1839, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, VMSS 774, series 2, box 1, folder 18–20. All transcriptions of Hyrum’s Liberty Jail letters and diaries are from the Hyrum Smith Papers Project directed by Craig K. Manscill.

[16] H. Dean Garrett, “Seven Letters from Liberty,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Missouri, ed. Arnold K. Garr and Clark V. Johnson (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1994), 189–90.

[17] The 1839 Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith letters are located at the Church History Library, Salt Lake City, MS 2779.

[18] Letter from Edward Partridge, 5 March 1839, http://

[19] One of the many alternate spellings of Grinnals.

[20] Letter from Don Carlos Smith and William Smith, 6 March 1839, http://

[21] The Joseph Smith Papers project has assigned a 20 March 1839 date to both parts of the “D&C 121–123 letter.” http://

[22] The LDS History of the Church incorrectly lists the date of this important letter as 25 March 1839. A note in that volume incorrectly states that it “was written between the 20th and 25th of March.” See History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 3:289.

[23] Letter to the Church and Edward Partridge, 20 March 1839–A, http://

[24] Dean C. Jessee and John W. Welch, “Revelations in Context: Joseph Smith’s Letter from Liberty Jail, 20 March 1839,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 125.

[25] Steven C. Harper, Making Sense of the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2008), 448.

[26] Letter to the Church and Edward Partridge, 20 March 1839–B, http://

[27] Letter to Emma Smith, 21 March 1939, http://

[28] Ripley had made previous visits to the jail. See History of the Reorganized Church, 2:315–23, and Holograph, Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 16 March 1839, MS 2779, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[29] Neal A. Maxwell, “A Choice Seer,” Ensign, August 1986, https://

[30] Holograph, Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 16 March 1839.

[31] Holograph, Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 19 March 1839.

[32] Holograph, Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, 20 March, 1839.

[33] Holograph, Hyrum Smith to Mary Fielding Smith, undated (written from Liberty Jail).

[34] “Statement of Hyrum Smith, July 1, 1843,” History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], 1617, http://

[35] “Statement of Hyrum Smith, July 1, 1843,” History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], 1618.

[36] “Statement of Hyrum Smith, July 1, 1843,” 1618.

[37] As noted by Jessee and Welch (page 131), the 20 March letter was published in the Times and Seasons (May and July 1840), the Deseret News, 26 January and 2 February 1854, and the Millennial Star, December 1840, October 1844, also 27 January and 10 February 1855.

[38] Church Historian’s Office, Journal (CR 100 1), 1844–1879, 15 January 1875, Church History Library. See also Journal History, 15 January 1875 and “New and Revised Edition of the Book of Doctrine and Covenants,” Historian Office Journal, 15 January 1875, 70.

[39] Richard E. Turley Jr. and William W. Slaughter, How We Got the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 98–99.