The Education of a Prophet

The Role of the New Translation of the Bible in the Life of Joseph Smith

David A. LeFevre

David A. LeFevre, "The Education of a Prophet: The Role of the New Translation of the Bible in the Life of Joseph Smith," in Foundations of the Restoration: The 45th Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, ed. Craig James Ostler, Michael Hubbard MacKay, and Barbara Morgan Gardner (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 99-120.

David A. LeFevre was an independent scholar in the Seattle area when this was published.

From June 1830 to July 1833, Joseph Smith labored on a new translation of the Bible, commonly known today as the Joseph Smith Translation (JST). During this time, the majority of the doctrines of the Church and the sections of the Doctrine and Covenants were first revealed or understood. The work on the JST and the receipt of these doctrines and revelations were not only overlapping in time but were directly related—the Lord used the work on the JST to reveal “many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God” (Articles of Faith 1:9).[1]

Joseph Smith’s view of the Bible was influenced by his day but was also unique. He believed in “the literality, historicity, and inspiration of the Bible.”[2] But unlike others, he didn’t believe the Bible alone was adequate to resolve important questions (see Joseph Smith—History 1:8–12). “Instead, he produced more scripture, scripture which echoed biblical themes, reinforced biblical authority, interpreted biblical passages, was built with biblical language, shared biblical content, corrected biblical errors, filled biblical gaps, and restored biblical methods. . . . Smith put himself inside the Bible story.”[3] That is the achievement of the JST.

The work on the Joseph Smith Translation was beneficial to the Church and especially to Joseph Smith, serving as his personal spiritual tutorial. Joseph Smith’s role “did include scriptural study, but it was grounded in direct revelation.”[4] His translation of the Bible was revelation, and revelation was how he learned the things of God.[5] This paper examines the correlation between concepts revealed to Joseph Smith through the work on the JST with those of his other revelations and teachings.

Beginning the Work

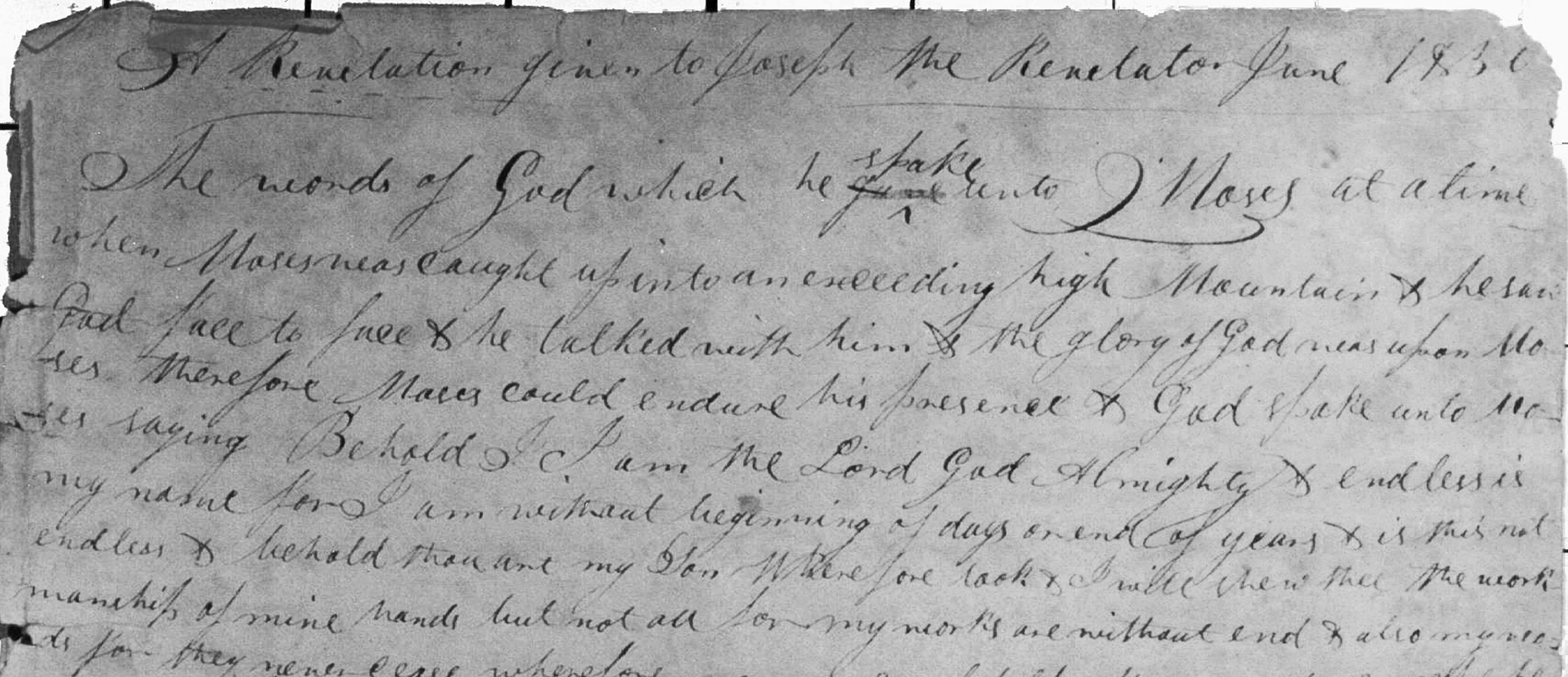

The Book of Mormon first went on sale at the end of March 1830.[6] A few days later, the Church was organized on 6 April 1830 (see D&C 20, heading). Shortly after those events, Joseph returned to Harmony, Pennsylvania, where he was living with his wife Emma. On 9 June 1830, the Prophet traveled to a Church conference held in Fayette.[7] At the end of June, he was in Colesville, New York, with his wife Emma, Oliver Cowdery, and John and David Whitmer to baptize and confirm members there (including Emma) when he was arrested and tried.[8] Between the conference and the Colesville visit, he was in Harmony.[9] It is likely that during this period at Harmony that Joseph Smith received a new revelation, recorded in the hand of Oliver Cowdery, that begins, “A Revelation given to Joseph the Revelator June 1830.”[10] This revelation related encounters Moses had with God and Satan after the burning bush incident but before he delivered the children of Israel out of bondage in Egypt.[11]

Figure 1: The vision of Moses, the start of the translation of the Bible. (Courtesy Community of Christ Archives.)

Figure 1: The vision of Moses, the start of the translation of the Bible. (Courtesy Community of Christ Archives.)

With that revelation, the work on the translation of the Bible began.[12] There is no recorded directive compelling the Prophet to do the work, though many subsequent revelations demonstrate that it was a divinely sanctioned part of his mission.[13] What is very clear from the beginning is that Joseph saw the translation as an important learning experience and a critical part of his calling. In the first mention of the JST work in a revelation, the Lord told Joseph in early July 1830, shortly after the vision of Moses in June, “& thou shalt continue in calling upon [God] in my name & writing the Things which shall be given thee by the Comforter & thou shalt expound all scriptures to unto the church & it shall be given thee in the very moment what thou shalt speak & write & they [the church] shall hear it . . . & in temporal labo[rs] thou shalt not have strength for this is not thy calling attend to thy calling & thou shalt have wherewith to magnify thine Office, & to expound all scriptures.”[14] Though the Prophet was receiving other revelations, the inspired translation of Genesis he was doing at this time was an important part of his writing of things given by the Comforter and led directly to his ability to “expound all scriptures” to the Church, which the Lord identified as a core part of his office.

It is interesting to note that in this effort, he was given “in the very moment” what to speak and to write, indicating that the work on the Bible was not so much an intense intellectual study as knowledge and understanding that flowed from the Spirit as they considered each passage. This “in the very moment” experience was similar to his efforts with the Book of Mormon translation, which was also completed “by the gift and power of God.”[15] This revelatory experience was surely why the Prophet considered his work on the Bible also a “translation,” even though no language but English was involved.[16] Another revelation reinforced this, given to Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and John Whitmer, who worked together on the Bible translation, just a few days later: “Behold I say unto you that ye shall let your time be devoted to the studying the Scriptures & to preaching & to confirming the Church.”[17]

Frederick G. Williams was called as a scribe to Joseph Smith as early as February or March of 1832.[18] His writing began in the JST in the book of Revelation, about 20 July 1832.[19] On 5 January 1833, as the translation was progressing through the Old Testament, Frederick G. Williams was called as a counselor to Joseph Smith and asked to continue his work as scribe. In that revelation not in the Doctrine and Covenants, the Lord declared, “My Servant Joseph is called to do a great work and hath need that he may do the work of translation for the salvation of souls.”[20] This was a work that was fully supported by the Lord.

Spiritual Lessons Learned

As the Prophet Joseph Smith worked his way through the Bible between June 1830 and July 1833, he was consistently tutored by the Spirit and taught eternal truths for his personal benefit and for the Church as a whole. Here are examples where Joseph Smith personally learned new truths that impacted his life and triggered additional revelations that were often recorded in the Doctrine & Covenants.

The nature of Satan. Joseph Smith had learned about Satan in a very personal way in his First Vision.[21] Early sections of the Doctrine and Covenants also mentioned “Satan” and “the devil” several times.[22] But D&C 29, given about 26 September 1830, revealed seemingly new information about Satan that is not found in the Bible nor understood by anyone in Joseph Smith’s day. In the revelation, the Lord explained that he made man “an agent unto himself” with commandments given to provide direction, but the devil “rebelled against me saying give me thine honour which is my Power” so that Satan might take away the agency of man. This rebellion was the cause of him and “a third part of the host of Heaven” being “thrust down” and thereby allowed to “tempt the children of men or they could not be agents unto themselves.”[23]

If all we had was the Doctrine & Covenants, we might view this information as new and unique. But this wasn’t the first time Joseph Smith had heard it. He had learned about Satan in June 1830 with the initial Visions of Moses,[24] but even more directly, what is now Moses 4:1-6 has the same concepts and similar wording as D&C 29—and it was translated from Genesis 3 prior to the revelation. The exact date Moses 4:1–6 was recorded is not known, but dates on the manuscript give us a range between June 1830 and 21 October 1830.[25] However, the text for that entire section is in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting, so we can narrow that range by looking at when Joseph and Oliver were together and likely to write. Oliver left Harmony and returned to live with the Whitmers in Fayette in mid-July,[26] while Joseph moved back to Fayette in early September.[27] After the Prophet arrived in Fayette, and until just before the 26 September conference, he and Oliver were at odds over the Hiram Page incident (D&C 28), making it unlikely they would work on the translation that month. October saw Oliver preparing to leave on his mission to the Lamanites. So the most likely date for all the material in Oliver’s handwriting (everything up to Moses 5:43a) is June–mid-July 1830, weeks before D&C 29.[28]

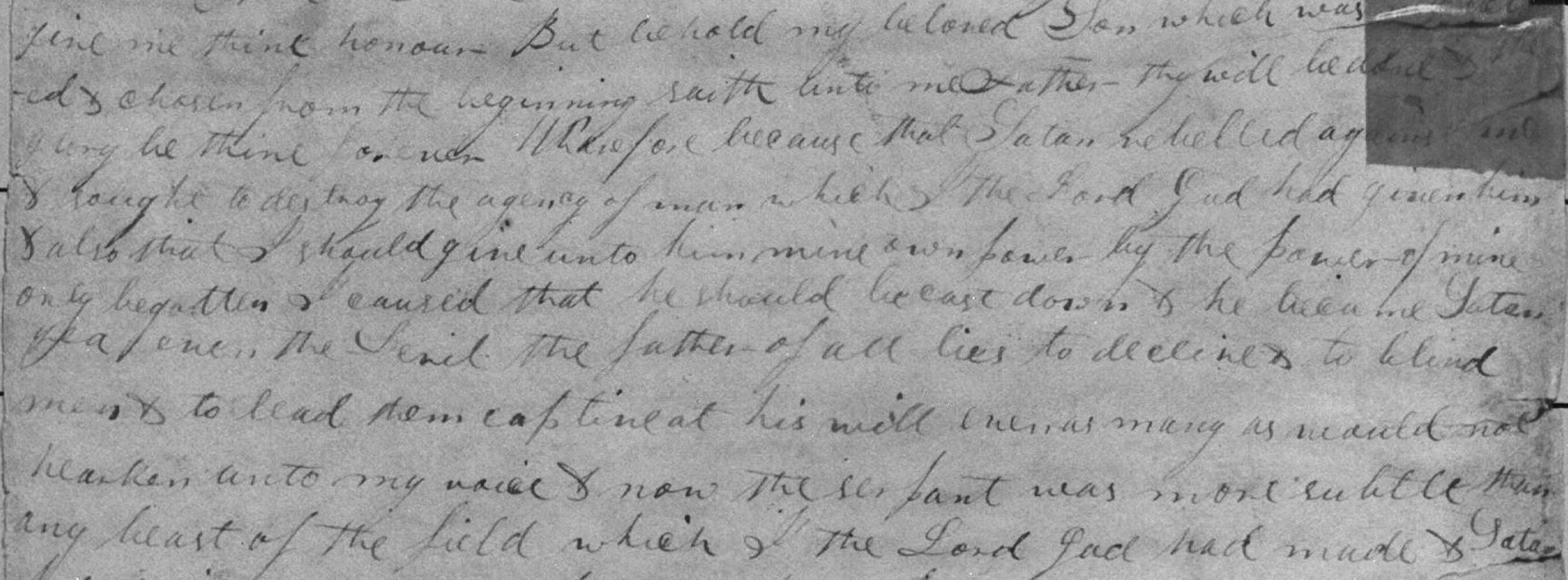

In the New Translation, Satan says, “Behold send me I will be thy son and I will redeem all mankind that one soul shall not be lost, and surely I will do it Wherefore give me thine honour.”[29] However, because Satan’s action was a rebellion to “destroy the agency of man” and an effort that God “should give unto him mine [God’s] own power,” Satan was “cast down,” becoming “the Devil the father of all lies to deceive & to blind men & to lead them captive at his will even as many as would not hearken” to the Lord’s voice.[30] The Prophet learned about Satan through the Bible translation and the Lord made that information directly relevant to the latter-day Church in D&C 29.

Figure 2: Close-up of page 6 of Old Testament Revision 1, showing Satan’s rebellion. (Courtesy of Community of Christ Archives.)

Figure 2: Close-up of page 6 of Old Testament Revision 1, showing Satan’s rebellion. (Courtesy of Community of Christ Archives.)

On several occasions, Joseph Smith taught from this understanding of the role of Satan in God’s plan. He said, “The devil has no power over us only as we permit him; the moment we revolt at anything which comes from God the Devil takes power.”[31] Furthermore, he explained, “Satan Cannot Seduce us by his Enticements unles we in our harts Consent & yeald—our organization such that we can Resest [resist] the Devil If we were Not organized so we would Not be free agents.”[32] In abbreviated notes, he was recorded to have taught, “The plans the devil laid to save the world.—Devil said he could save them all—Lot fell on Jesus.”[33] Applying this understanding to the Saints in an 1841 discourse, Joseph said, “Satan was generally blamed for the evils which we did, but if he was the cause of all our wickedness, men could not be condemned. The devil cannot compel mankind to evil, all was voluntary.— Those who resist the spirit of God, are liable to be led into temptation, and then the association of heaven is withdrawn from those who refuse to be made partakers of such great glory—God would not exert any compulsory means and the Devil could not; and such ideas as were entertained by many were absurd.”[34]

Zion and the New Jerusalem. Joseph Smith’s understanding of the terms “Zion” and “New Jerusalem” clearly changed and deepened with the translation work and related revelations. From the Book of Mormon’s forty-five references and others in the Bible, he would have understood that Zion generally referred to Jerusalem or was “a holy community, a fortification of the Saints against evil,”[35] while “New Jerusalem” referred to a city that will be built as the gathering place of the righteous[36] and another city of unknown origin which will come again.[37] References to “Zion” in the Prophet’s early revelations take that same meaning; several Saints in 1830 were called to “seek to bring forth and establish the cause of Zion” (D&C 6:6; see also 11:6; 12:6; 14:6; 24:7). The first hint that Zion was a different place than Jerusalem was in a revelation to Oliver Cowdery in late September 1830. In relation to things Hiram Page had falsely said, Oliver was told, “Now Behold I say unto you that it is not Revealed & no man knoweth where the City shall be built But it shall be given hereafter.”[38] The city was the New Jerusalem or Zion.[39]

There is no immediate explanation for a shift in revelatory meaning of “Zion”—the Lord simply started referring to it as a new city starting with D&C 28. But like Adam, who first sacrificed and then had it explained to him (see Moses 5:5–8), the details soon came to the Prophet through the work on the Bible and the revelations it triggered. In early December 1830, after Sidney Rigdon’s arrival in Fayette to meet Joseph Smith, they recorded what is now Moses 7:13–21, where they learned about Enoch’s people and city, how the people were called Zion as was the city, and that the city was taken up into heaven. On 2 January 1831, an almost casual reference is made to Enoch’s Zion as the Lord described himself: “I am the same which hath taken the Zion of Enoch into mine own bosom.”[40] Without the context of Moses 7, that remark would make little sense—in the Bible, there is no mention of Enoch with a city called Zion. On 7 March 1831, another revelation spoke of the righteous gathering to Zion and the wicked being afraid of it (D&C 45:67–71), which echoes what Joseph Smith had already learned the previous December, that all nations greatly feared Enoch’s Zion because Enoch “spake the word of the Lord and the earth trembled and the Mountains fled even according to his command and the rivers of water were turned <out> of their course and the roar of the Lions was heard out of the willderness.”[41]

In terms of the “New Jerusalem,” the work in Genesis built upon what was in the Book of Mormon. In December 1830, Joseph and Sidney Rigdon learned that Zion was equated with the New Jerusalem: “a place which I shall prepare an holy City that my people may gird up their loins and be looking fourth for the time of my coming for there shall be my tabernicle and it shall be called Zion a New Jerusalem.”[42] That city would be the abode of God during the “thousand years the earth shall rest” (Moses 7:64). The first mention of the term “New Jerusalem” in the Doctrine and Covenants is about two months later, on 9 February 1831 in D&C 42:9 (also vv. 35, 62, and 67). “Mount Zion” and “New Jerusalem” are first mentioned together even later, on 3 November 1831 (see D&C 133:56) and not equated until 22–23 September 1832 (see D&C 84:2). In other words, Joseph Smith learned these concepts through his work on the Bible at least a year before they were made clear in the Doctrine and Covenants.

On 20 July1831, the Prophet revealed to the Church the promised location of Zion, the New Jerusalem, in the last days—Independence, Missouri (see D&C 57:1–2). There the Saints would gather and build a temple (see D&C 57:3). Subsequent revelations throughout 1832–1834 developed and directed this activity, including the attempt to redeem Zion with an army (see D&C 103). As the Saints were driven from Jackson County into Clay and Caldwell counties, and eventually out of Missouri entirely, the Prophet’s definition of “Zion” enlarged, finally coming to take in all of North and South America.[43]

The importance of Zion to Joseph Smith is reflected in an 1839 discourse—after their failure to establish a city in Missouri—when Joseph Smith said, “We ought to have the building up of Zion as our greatest object.—when wars come we shall have to flee to Zion, the cry is to make haste.”[44] However, his most expansive definition of “Zion” came before the Saints had even gone to Missouri: “The Lord called his people Zion because they were of one heart and of one mind and dwelt in righteousness and there was no poor among them.”[45] Later, before Joseph knew of the troubles just beginning in Missouri, in a revelation he received just one month after he finished the work on the Bible, the Lord said simply, “Zion [is] the pure in heart.”[46]

One historian noted, “The City of Zion occupied a central place in Joseph Smith’s design for world renewal. He conceived the world as a vast funnel with the city at the vortex and the temple at the center of the city. Converts across the globe would be attracted to this central point to acquire knowledge and power for preaching the gospel. Trained and empowered in the temple, the missionary force would go back into the world and collect Israel from every corner of the earth. The city, the temple, and the world, existed in a dynamic relationship. Missionaries flowed out of the city and converts poured back in. The exchange would redeem the world in the last days.”[47]

The law of consecration. Closely related to the concept of Zion is the revelation on “the law” (D&C 42:2). The growing understanding and application of this law spanned several years, with the Bible translation experiences playing a major role in its advancement.

As mentioned above, after Sidney Rigdon’s arrival in Fayette in December 1830, he began to scribe for Joseph Smith on the translation work. The first thing they worked on was what is now Moses 7, where they learned about Enoch protecting his people with miraculous priesthood power (Moses 7:13); that his people and their city were called Zion because “they were of one heart and of one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them” (v. 18); and that Zion was taken (v. 69). Just a few days later, a revelation was received in which the Lord identified himself as “the same which have taken the Zion of Enoch into mine own bosom” (D&C 38:4). Following Zion’s example, the Saints were counseled to “let evry man esteem his Brother as himself . . . I say unto you be one & if ye are not one ye are not mine.” The Church was also commanded to “look to the poor & the needy & administer to their relief that they shall not suffer.”[48]

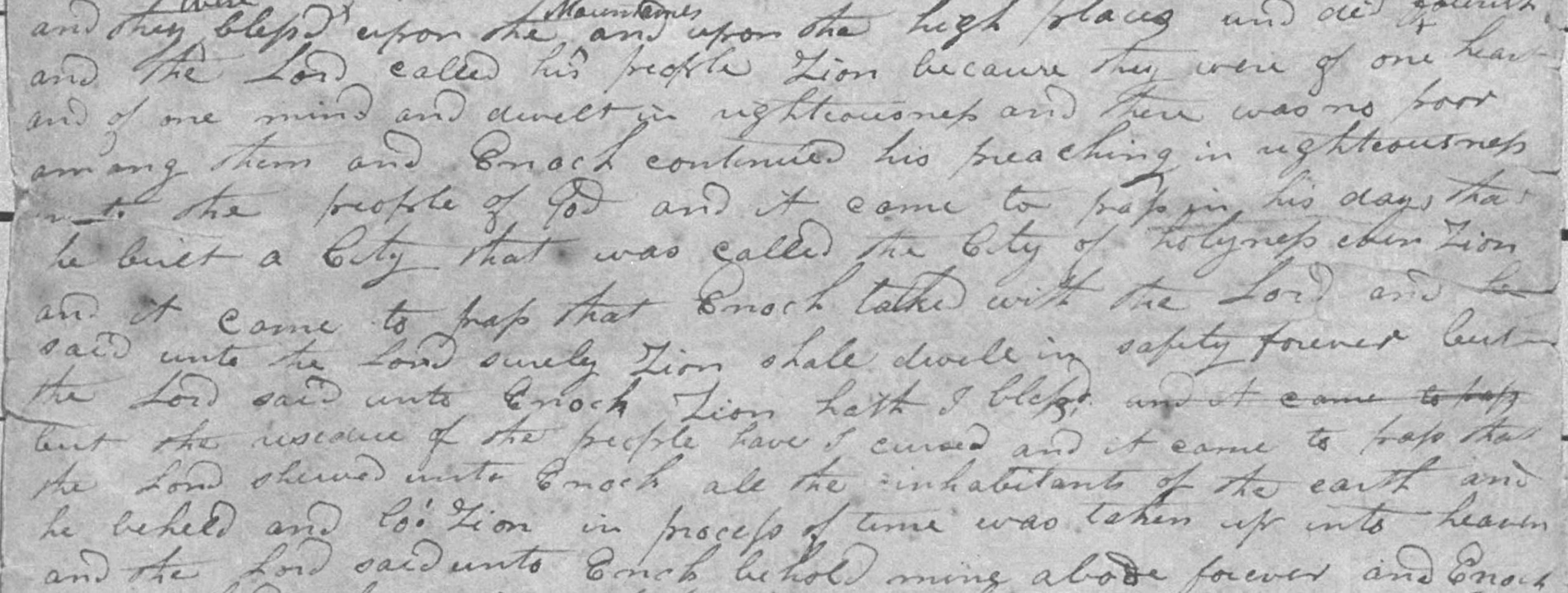

Figure 3: Old Testament Revision 1, page 16, showing the reference to Zion and no poor among them. (Courtesy of Community of Christ Archives.)

Figure 3: Old Testament Revision 1, page 16, showing the reference to Zion and no poor among them. (Courtesy of Community of Christ Archives.)

After a cold trip in late January/

Just five days later, 9 February 1831, the first revelation on that law was received, titled “The Laws of the Church of Christ” by John Whitmer.[51] This document answered five questions posed to Joseph Smith by twelve elders, the second of which concerned “The Law.” After reciting a number of commandments (don’t kill, steal, commit adultery, or speak evil of a neighbor; do love your wife), the Lord stated, “If thou lovest me thou shall serve & keep all my commandments & Behold thou shalt consecrate all thy property properties that which thou hast unto me with a covena[n]t and Deed which cannot be broken & they Shall be laid before the Bishop of my church & two of the Elders such as he shall appoint & set apart for that purpose.”[52] Unlike the communal efforts of the Kirtland Saints previously, this system relied on a bishop to make “every man a Steward over his own property or that which he hath received . . . that every man may receive according as he stands in need.”[53] The remainder would be managed by the bishop in a storehouse to take care of the poor and needy.[54] This was the latter-day implementation of the doctrines of Zion and caring for the poor taught to the Prophet through the Enoch chapters, which information prepared him to receive and teach this law.

On 6 June 1831, another revelation was given on the second day of a conference held in Kirtland. The brethren were told that their next conference was to be in Missouri, and they were to travel there two by two, preaching as they went. Missouri was “the land which I will consecrate unto my People,”[55] and they were to “assemble yourselves together to rejoice upon the land of your inheritance which is now the land of your enemies but behold I the lord will hasten the City in its time.”[56]

Finally, once all had arrived in Missouri, Joseph Smith pondered the question of where the holy city of Zion should be built. The brethren were in Independence, on the western border of Missouri, when the revelation was given on 20 July 1831: “Wherefore, this is the land of promise & the place for the City of Zion. . . . Behold the place which is now called Independence is the centre place, & the spot for the Temple is lying westward upon a lot which is not far from the court-house.”[57]

The history of the Saints in Missouri is well-documented in the Doctrine and Covenants and an abundance of books of the Church history of the period. Trying to make Zion flourish in Missouri became a core focus of Joseph Smith and many others in the Church for several years. The effort that started all the questions and triggered the revelations was the Prophet’s experience and learning gained through translating the Bible. This is surely one of the great reasons the Lord directed Joseph Smith to perform the labor of the translation in the first place, for even today “The Law” of consecration and stewardship forms a foundational structure upon which the entire ability of the Church to function and be successful is based.

The age of accountability. One of the most widely noticed chains of learning experiences related to the Bible translation is with the age of accountability.[58] The Book of Mormon has nearly an entire chapter devoted to idea that “little children need no repentance, neither baptism” (Moroni 8:11), but the age when they do need repentance and baptism is not given. In June 1829, as the brethren were finishing up the translation of the Book of Mormon, the Prophet received a revelation directing that “all men must repent and be baptized; and not only men, but women and children, which have arriven to the years of accountability,”[59] but again, the age of accountability was not given.

In the period of February–March 1831, Joseph Smith and Sidney Ridgon were working through the Genesis chapters about Abraham.[60] In Genesis 17 they learned that people had turned away from the ordinances of “anointing and the buriel or baptism wherewith I commanded them.” Instead, they were washing children and sprinkling blood. The Prophet must have rejoiced when in Abraham’s discussion with the Lord, Abraham was instructed to make a covenant of circumcision with the Lord, part of which was designed to teach “that children are not accountable before me till eight years old.”[61] This was a very practical and needed piece of information to correctly apply the doctrine of accountability.

Later that year, at a Church conference held in Hiram, Ohio, on 1 November 1831, the Lord was instructing parents in the Church in their responsibilities toward their children: “And again inasmuch as parents have children in Zion that teach them not to understand the doctrine of repentance faith in Christ the Son of the living God & of baptism & the gift of the Holy Spirit by the laying <on> of the hands when eight years old the sin be upon the head of the parents for this shall be a Law unto the inhabitants of Zion & their children shall be baptised for the remission of their sins when eight years old & receive the laying on of the hands & they also shall teach their children to pray & to walk uprightly before the Lord.”[62] The information about the age of eight is noted not as new information but as something already understood—which it was to the Prophet and others with whom he shared it after the Genesis translation. The emphasis in the revelation is rather on how parents prepare their children for baptism and the laying on of hands when they arrive at eight years old.

Joseph Smith had several children die before the age of eight.[63] In 1836, while in the Kirtland Temple, he received a vision that included the amazing discovery that “all children who die before they arrive at the years of accountability are saved in the celestial kingdom of heaven” (D&C 137:10). Knowing that their small children were not accountable and would be exalted must have brought great comfort to him and Emma, as it does to millions today.

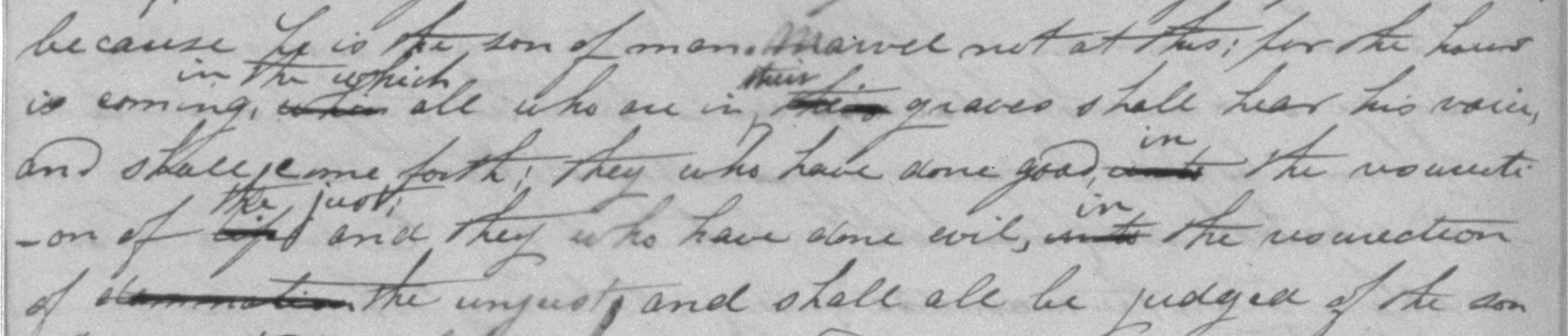

The degrees of glory. One of the clearest links between the translation work and significant new knowledge occurred on 16 February 1832. Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon were living at Hiram, Ohio, and had progressed in the translation work to John chapter 5. When they first encountered John 5:29, Rigdon wrote it in the manuscript fundamentally the same as it appeared in the King James Bible they were using as a reference: “And shall come forth; they who have done good, unto the resurection of life and they who have done evil, unto the resurection of damnation.”[64] Then the men paused, being “in the spirit . . . and through <by> the power of the spirit our eyes were opened and our understandings were enlarged so as to see and understand the things of God.”[65] In this state, they understood a change needed to be made to the verse, and they recorded it so: “And shall come forth; they who have done good, unto <in> the resurection of life <the just;> and they who have done evil, unto <in> the resurection of damnation the unjust.”[66] The bracketed words were inserted above the crossed out words, showing they had to squeeze them in above the already-written verse, but the phrase “the unjust” was added after the crossed-out “damnation,” indicating the pause before the edits, as they had room to write the final phrase on the same line.[67] The men wrote that this small change of six words “caused us to marvel for it was given <unto> us of the spirit.”[68] Then they had a lengthy visionary experience where they saw and conversed with Jesus Christ, who was on the right hand of the Father, and witnessed angels and others before the throne of God. They saw the fall of Lucifer, learned about “sons of perdition,” then learned about those saved in three different kingdoms of glory—celestial, terrestrial, and telestial.

Figure 4: New Testament Revision 2, part 4, page 114, showing John 5:29 revisions. (Courtesy of Community of Christ Archives.)

Figure 4: New Testament Revision 2, part 4, page 114, showing John 5:29 revisions. (Courtesy of Community of Christ Archives.)

This vision had a powerful impact on Joseph Smith. After receiving it, he used the language of D&C 76 in sermons, letters, prayers, and more.[69] In his history, he is recorded to have said, “Nothing could be more pleasing to the Saint, upon the order of the kingdom of the Lord, than the light which burst upon the world, through the foregoing vision. . . . [It] witnesses the fact that that document is a transcript from the Records of the eternal world. The sublimity of the ideas; the purity of the language; the scope for action; the continued duration for completion, in order that the heirs of salvation, may confess the Lord and bow the knee; The rewards for faithfulnes & the punishments for sins, are so much beyond the narrow mindedness of men, that every honest man is constrained to exclaim; It came from God.”[70]

Wheat and tares. This parable in Matthew 13 was first recorded in the translation effort probably in April or May 1831, and was first written fundamentally as it stands in the King James Version.[71] The key verse (30) had no changes: “Let both grow till <untill> the harvest and in the time of harvest I will say to the reapers gather ye together first the tares and bind them in bundles to burn them but gather the wheat into my barn.”[72] Shortly after that, John Whitmer made a copy of the first New Testament manuscript and kept the wording exactly the same.[73] After the brethren completed the work on the New Testament at the end of July 1832, they turned their attention back to the Old Testament.[74] However, Joseph and Sidney continued to make revisions in the New Testament manuscript until 2 February 1833.[75] Sometime during this review, the words “gather ye together first the tares & bind them in bundles to burn them but gather the wheat into my Barn” were crossed out in New Testament 2 and a note was pinned over the text as follows: “Gather ye together first the wheat into my barns, and the tares are bound in bundles to be burned.”[76]

On 6 December 1832, Joseph Smith personally wrote in his own journal, “December 6th translating and received a Revelation explaining the Parable the wheat and the tears [tares] &c.”[77] The resulting revelation (D&C 86) gives a marvelous latter-day interpretation of the parable, including the same reversal of the order of the harvest expressed on the pinned note. Both the pinned note and the original revelation were in the handwriting of Sidney Rigdon, especially significant because Frederick G. Williams was the principal scribe for the translation in December 1832.[78] Though we don’t know the date of the pinned note with certainty, the journal entry for the revelation gives the impression of cause and effect—“translating and received a Revelation.” It is reasonable then, that, like section 76 and similar experiences, the change was first made to the biblical text by inspiration, which then triggered the larger revelation recorded in the Doctrine and Covenants.

The reversal of the order was significant to the message of the Restoration. About a year previous, the Lord had told the Church to “flee unto Zion” and “flee unto Jerusalem.” They were to come “out from among the nations” and “from the midst of wickedness,” separating themselves from the wicked, “which is spiritual Babylon” (D&C 133:12–14; see also verses 4–5, 36–38, all of which focus on the Church’s mission and message to gather the righteous out of the wicked world). This then became a main mission of the Church and drove the Prophet to send missionaries abroad and men to preach the gospel in many nations. Changing the parable to gather the wheat first aligned with that vision and mission and was good doctrine. D&C 86 put the interpretation squarely in a latter-day context: “But behold in the last days, even now while the Lord is begining to bring forth his <the> word, and the blade is springing up and is yet tender,” the angels are anxiously waiting to start the harvest. But the Lord refrains them: “Pluck not up the tears while the blade is yet tender (for verily your faith is weak) least you distroy the wheat also, therefore let the wheat and the tears grow together untill the harvest is fully ripe then ye shall first gather out the wheat.”[79]

A couple of years later, Joseph Smith explained it this way: “We understand that the work of the gathering together of the wheat into barns, or garners, is to take place while the tares are being bound over and preparing for the day of burning.”[80] The wheat may be first, but both types of harvest are the work of the latter-days.

Israel and the priesthood. Joseph Smith had been learning about the priesthood since his ordination by John the Baptist in May 1829 (see D&C 13) and through the early 1830s. The work on the Bible translation was an important avenue for his increased understanding. While translating Genesis 14 (probably in February 1831), he learned significant new information about Melchizedek, including that Melchizedek “was ordained a high priest after the order of the covenant which God made with Enock it being after the order of the Son of God.”[81] About a year later, while working through Hebrews 7, it was revealed: “For this Melchisedec was ordained a priest after the order of the son of God, who was <which order was> without father, without mother, without descent, having neither begining of days, nor end of life; and all those who are ordained unto this Priesthood, are made like unto the son of God, abiding a Priest continually.”[82]

Then in September 1832, after returning from Missouri and resuming the work on the Old Testament, two similar passages were changed to instruct how the priesthood was handled among the Israelites in Moses’s day. The first was in the opening verses of Exodus 34: “And the Lord said unto Moses, hew thee two other tables of stone, like unto the first, and I will write upon them also, the words of the Law, according as they were writen at the first, on the tables which thou breakest; but it shall not be according to the first, for I will take away the priest-hood out of there midst; therefore my holy order; <and the ordinances thereof,> shall not go before them; for my pressence shall not go up in there midst Least I distry [destroy] them,<.>”[83]

The second was Deuteronomy 10:1–2 that reinforced his learning from Exodus: “At that time the Lord said unto me, hewe thee two other tables of stone, like unto the first, and come up unto me upon the mount, and make thee an ark of wood,<.> And I will write on the tables the words that were on the first tables which tho breakest, save the words of the <everlasting> covenant of the holy Priesthood, and thou shalt put them in the ark,<.>”[84]

The culminating revelation from all this work was given on 22 September 1832, just after these changes, today section 84.[85] Joseph Smith learned that Moses received “the holy Priesthood” from his father-in-law, Jethro,[86] who received it through a chain of ordinations that originated with Abraham, who “received the Priesthood from Melchesedec who received it through the lineage of his fathers even till Noah, and from Noah till Enoch, through the lineage of thare fathers,”[87] who could trace his priesthood lineage back to Adam. The priesthood “continueth in the church of God in all generations.”[88] Compared to the priesthood of Aaron, this “holiest order of God” is the “greater Priesthood” and without it and its associated ordinances, “the power of Godliness is not manifest unto man in the flesh.”[89] Referring back to Joseph’s recent translation work in Exodus and Deuteronomy, the Lord clarified, “Now this Moses plainly taught to the children of Israel in the wilderness and saught diligently to sanctify his people that they might behold the face of God, but they hardened ther hearts and could not endure his presence,” so the Lord took the holy priesthood away from them.[90]

Priesthood offices and authority were largely unknown concepts in Joseph Smith’s day.[91] The Prophet had to be tutored so that he could understand the authority he had received from divine messengers and then administer that throughout the Church. Matthew C. Godfrey argued:

The Lord taught these truths to Joseph through a variety of means, including providing inspiration as Joseph worked on his translation of the Bible and giving Joseph additional revelations that clarified priesthood doctrine and responsibilities. Joseph, in turn, conveyed these teachings through his revelations and through conferences of elders and high priests. . . . In the years that followed, the Lord would reveal more to the Prophet about priesthood; by 1835, for example, the greater priesthood, or the umbrella under which all offices of the priesthood exist, was known as the Melchizedek Priesthood, and the lesser priesthood was called the Aaronic Priesthood. But the doctrines revealed in the Church’s initial years provided the foundation for this understanding, making what Joseph taught about the priesthood in the early years of the Church even more significant.[92]

Conclusion

The Prophet Joseph Smith was a man who thoroughly engaged with the scriptures. He studied them intensely and sought revelation as he did so. His translation of the Bible, which was done by the Spirit of God, like the Book of Mormon translation, is a model for how the study of the scriptures can stimulate revelation in our own lives. As Joseph pondered the words on those sacred pages and asked questions that thereby came to his mind, the Lord revealed answers to him. In his role as the Prophet of the Restoration, many of his answers impacted not only his own life but the entire path of the Church in the last days. While our own revelations may not have the same scope, they are nevertheless personally significant. Studying scripture is a catalyst to personal revelation, an effort we make to show the Lord that we seriously seek his voice, need his guidance, and desire to be “a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge” (Abraham 1:2). Joseph Smith demonstrated through his work on the translation of the Bible that such an effort is well rewarded.

Notes

[1] Robert J. Matthews, in his groundbreaking work on the translation, called the abundance of revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants during the work on the Joseph Smith Translation “not coincidental but consequential.” Robert J. Matthews, “A Plainer Translation”: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible—A History and Commentary (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 265.

[2] Philip L. Barlow, “Before Mormonism: Joseph Smith’s Use of the Bible, 1820–1829,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, LVII/

[3] Barlow, “Before Mormonism,” recognizing that Barlow is speaking mostly of the Book of Mormon and revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants, given the time period of his article, but what he says applies equally to the translation of the Bible.

[4] Barlow, “Before Mormonism,” 763.

[5] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 388.

[6] Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publications of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2015), 215.

[7] Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, vol. 1 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 139.

[8] Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds. Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844, vol. 1 of the Histories series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 390–412; see also page 552 in the same volume that gives the date of Joseph Smith’s arrest and trial at Colesville that occurred at this time as 28 June–1 July, 1830.

[9] History Drafts, 1838—Circa 1841, Draft 1 and Draft 2, in JSP, H1:390.

[10] Visions of Moses, June 1830, in JSP, D1:152.

[11] Moses 1:17 shows that it was after the burning bush encounter recorded in Exodus 3, and Moses 1:26 proves that the deliverance from Egypt was yet to happen.

[12] It’s not clear that the initial “Visions of Moses” revelation was immediately linked to the translation process in the minds of Joseph and Oliver, or how long it was after that revelation that they turned to the first chapter of Genesis. But the same document used to record the initial revelation became the one used for the translation, and the copies made later all included the vision. That some time passed between what is now Moses 1 and the work on Genesis seems evident by the formatting (strong lines dividing the vision from the rest of the text) and a note at the start of Genesis chapter 1: “A Revelation given to the Elders of the Church of Christ On the first Book of Moses given to Joseph the Seer.” Old Testament Revision 1, p. 3, in Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004), 86.

[13] For example, D&C 45:60–61 directs the Prophet to start the translation of the New Testament with this counsel, showing the Lord gave him the work: “And now, behold, I say unto you, it shall not be given unto you to know any further concerning this chapter, until the New Testament be translated, and in it all these things shall be made known; Wherefore I give unto you that ye may now translate it, that ye may be prepared for the things to come” (emphasis added).

[14] Revelation, July 1830-A [D&C 24], in JSP, D1:158–59 (emphasis added); see D&C 24:5–6, 9.

[15] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Book of Mormon Translation,” https://

[16] D&C 76:15 and chapter heading to that section quoting from History of the Church; see also D&C 45:60–61. The work is referred to as the “new translation” in many documents, such as D&C 124:89 and a verse originally in the revelation that is now D&C 104 (the deleted section would be after verse 59 today) with the Lord telling the brethren to seek “the copy right to the new translation of the scriptures” so “that others may not take the blessings away from you which I conferred upon you.” Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Manuscript Revelation Books, facsimile edition, first volume of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2009), 369. The latter quote significantly shows the Lord’s attitude that the work on the translation was a great blessing to Joseph and the early Church.

[17] Revelation, July 1830-B [D&C 26], in JSP, D1:160 (emphasis added); see D&C 26:1.

[18] Letter to William W. Phelps, 31 July 1832, in Matthew C. Godfrey, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 2: July 1831–January 1833, vol. 2 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 267n337.

[19] Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible, 47; Revelation, 5 January 1833, in JSP, D2:357.

[20] Revelation, 5 January 1833, in JSP, D2:361.

[21] See Joseph Smith—History 1:15–17; see also History, circa June 1839–circa 1841 [Draft 2], in JSP, H1:212-214.

[22] E.g. D&C 10:5, 10, 12, 14, 20, 22–27, 29, 32–33; 18:20; and 19:3.

[23] Revelation, September 1830-A [D&C 29], in JSP, D1:181.

[24] See Moses 1:12–24.

[25] Faulring, et al, Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible, 57.

[26] See History Drafts, 1838—Circa 1841, Draft 1 and Draft 2, in JSP, H1:424; and Revelation, July 1830-A [D&C 24], Historical Introduction, in JSP, D1:157n220.

[27] See Chronology, in JSP, H1:552.

[28] My examination of the handwriting on the manuscripts also supports continuous work for the entire section, with similar ink flow and color right up to the point where the handwriting changes to John Whitmer’s handwriting.

[29] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 6, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 90. The phrase in Moses 4:1 today is, “Behold, here am I, send me,” with the words “here am” being added by James E. Talmage in the 1902 edition of the Pearl of Great Price that he prepared. Kent P. Jackson, The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 43.

[30] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 6, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 90.

[31] 5 January 1841 (Tuesday), Old Homestead, Extracts from William Clayton’s Private Book, in Ehat and Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith, 60.

[32] 16 March 1841 (Tuesday), McIntire Minute Book, in Ehat and Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith, 65.

[33] 7 April 1844 (Sunday afternoon), at the temple, Joseph Smith Diary, by Willard Richards, in Ehat and Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith, 342.

[34] 16 May 1841 (Sunday morning), at meeting ground, Times and Seasons 2 (1 June 1841): 429–430, in Ehat and Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith, 72.

[35] Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan, eds., Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 1397. The Book of Mormon references they give in support are 1 Nephi 13:37; 2 Nephi 10:11–13; 26:29–31; 28:20–21, 24.

[36] E.g., 3 Nephi 20:22; 21:23–24; and Ether 13:5.

[37] E.g., Ether 13:3–4, 10; it has a similar meaning in Revelation 3:12 and 21:2.

[38] Revelation, September 1830-B [D&C 28], in JSP, D1:185–86; see D&C 28:9.

[39] Revelation, September 1830-B [D&C 28], in JSP, D1:186n361.

[40] Revelation, 2 January 1831 [D&C 38], in JSP, D1:230; see D&C 38:4.

[41] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 16, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 104; see Moses 7:13.

[42] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 19, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 109; see Moses 7:62.

[43] Glossary, “Zion,” in JSP, D1:505.

[44] Before 8 August 1839 (1), Willard Richards Pocket Companion, in Ehat and Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith, 11.

[45] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 16, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 105; see Moses 7:18.

[46] Revelation, 2 August 1833-A [D&C 97], in Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Brent M. Rogers, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds. Documents, Volume 3: February 1833–March 1834, vol. 3 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2014), 202; see D&C 97:21.

[47] Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, 220–21.

[48] Revelation, 2 January 1831 [D&C 38], in JSP, D1:232–33; see D&C 38:4, 25–27, 24–25.

[49] Stephen E. Robinson and H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, vol. 2 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 1–2; Revelation, 4 February 1831 [D&C 4], Historical Introduction, in JSP, D1:241–242.

[50] Revelation, 4 February 1831 [D&C 41], in JSP, D1:244; see also D&C 41:3.

[51] Revelation, 9 February 1831 [D&C 42:1–72], in JSP, D1:249.

[52] Revelation, 9 February 1831 [D&C 42:1–72], in JSP, D1:251.

[53] Revelation, 9 February 1831 [D&C 42:1–72], in JSP, D1:252.

[54] Revelation, 9 February 1831 [D&C 42:1–72], in JSP, D1:252.

[55] Revelation, 6 June 1831 [D&C 52], in JSP, D1:328.

[56] Revelation, 6 June 1831 [D&C 52], in JSP, D1:332.

[57] Revelation, 20 July 1831 [D&C 57], in JSP, D2:7–8.

[58] For example, see Matthews, “A Plainer Translation,” 260, 317; Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler, Revelations of the Restoration (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 492–93; Revelation, 1 November 1831-A [D&C 68], in JSP, D2:102n179.

[59] Revelation, June 1829-B [D&C 18], in JSP, D1:73; see D&C 18:42.

[60] On 10 December 1830, Sidney Rigdon began to write at what is now Moses 7:2. Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible, 57 and 103; see D&C 35:20. On 30 December 1830 they stopped the translation process at the Lord’s direction, shortly after receiving the Enoch material in the Book of Moses. Revelation, 30 December 1830 [D&C 37], in JSP, D1:226–27. The translation did not resume until the brethren relocated to Kirkland, Ohio, on 4 February 1831. Revelation, 4 February 1831 [D&C 41], in JSP, D1:241. The work on the Old Testament ended temporarily at Genesis 24:41a on 7 March 1831 when they were commanded to begin work on the New Testament (D&C 45:60–61). Thus the chapters on Abraham in Genesis 12:1–24:41a were the focus in February–March 1831.

[61] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 41, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 131-132.

[62] Revelation, 1 November 1831-A [D&C 68], in JSP, D2:102 (emphasis added); see D&C 68:25-28.

[63] Five of the Smith’s children died in infancy; see, Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, 425.

[64] New Testament Revision 2, part 4, p. 114, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 454.

[65] Revelation Book 2, 16 February 1832 [D&C 76], in JSP, MRB:414–17; see D&C 76:11–12.

[66] New Testament Revision 2, part 4, p. 114, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 454.

[67] Rigdon drew a bold line down across two lines just after the word “unjust,” which later was written over by a semicolon and a letter in the line below it, further emphasizing the dramatic pause they experienced.

[68] Revelation Book 2, 16 February 1832 [D&C 76], in JSP, MRB:417; see D&C 76:18.

[69] For example, see http://

[70] History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], page 192, The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[71] There were some minor changes that do impact the meaning of the text, such as changing “which” to “who” in verse 24 and dropping the word “was” from verse 26 to smooth out the reading.

[72] New Testament Revision 1, p. 34, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 192.

[73] New Testament Revision 2, part 1, p. 25, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 267.

[74] Joseph Smith declared the translation work on the New Testament done in his letter to W. W. Phelps, dated 31 July 1832: “We have finished the translation of the New testament great and marvilous glorious things are revealed, we are making rapid strides in the old book [Old Testament].” Letter to William W. Phelps, 31 July 1832, in JSP, D2:267.

[75] Minute Book 1 has an entry dated 2 February 1833 by Frederick G. Williams that states, “This day completed the translation and the reviewing of the New testament and sealed up no more to be broken till it goes to Zion.” Minute Book 1, page 8, The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[76] New Testament Revision 2, part 1, p. 25, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 267; emphasis added.

[77] Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., Journals, Volume 1: 1832–1839, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 11.

[78] New Testament Revision 2, part 1, p. 25, in Faulring et al., Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 267n1 explains that the pinned note was “in Sidney Rigdon’s handwriting.” Though we don’t have the original copy of D&C 86, the early copy made by Frederick G. Williams affirms that it was “written by Sidney [Rigdon] the scribe an[d] Counsellor.” Revelation, 6 December 1832 [D&C 86], in JSP, D2:327. Williams was the scribe for the Old Testament work then going on and some of the New Testament revisions, but Rigdon did much of the revision writing. Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 59.

[79] Revelation, 6 December 1832 [D&C 86], in JSP, D2:326; see D&C 86:4–7.

[80] Messenger and Advocate, December 1835, 226–29, cited in Kent P. Jackson, ed., Joseph Smith’s Commentary on the Bible (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 95.

[81] Old Testament Revision 1, p. 34, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 127.

[82] New Testament Revision 2, part 4, p. 139, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 539.

[83] Old Testament Revision 2, p. 70, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 701.

[84] Old Testament Revision 2, p. 72, in Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 709.

[85] The revelation was received over two days, 22–23 September 1832, but the section containing the information about the priesthood is in the beginning verses and was thus confined to 22 September.

[86] Revelation, 22–23 September 1832 [D&C 84], in JSP, D2:293; see D&C 84:6.

[87] Revelation, 22–23 September 1832 [D&C 84], in JSP, D2:295; see D&C 84:14–15.

[88] Revelation, 22–23 September 1832 [D&C 84], in JSP, D2:295; see D&C 84:17.

[89] Revelation, 22–23 September 1832 [D&C 84], in JSP, D2:295, see D&C 84:19–21.

[90] Revelation, 22–23 September 1832 [D&C 84], in JSP, D2:295–96; see also D&C 84:23–25.

[91] Matthew C. Godfrey, “A Culmination of Learning: D&C 84 and the Doctrine of the Priesthood,” in You Shall Have My Word: Exploring the Text of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Scott C. Esplin, Richard O. Cowan, and Rachel Cope (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 170–71.

[92] Godfrey, “Culmination of Learning,” in You Shall Have My Word: Exploring the Text of the Doctrine and Covenants, 178.