Gospel Messengers Return to Iceland

Fred Woods, “Gospel Messengers Return to Iceland ,” in Fire on Ice: The Story of Icelandic Latter-day Saints at Home and Abroad, (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 105–49.

Although there was no organized LDS Icelandic branch between 1914 and 1974, in 1930 two full-time missionaries were sent to Iceland from the Danish Mission to serve for a few months: James C. Ostegar and F. Lynn Michelsen. [1] A visit to Copenhagen by a returning missionary in 1938 revealed that after these missionaries had spent a summer in Iceland, they were called back “thinking it was not of any use.” [2]

Soon after visiting the Danish Mission in 1955, Elder Spencer W. Kimball, a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, wrote a letter to Church President David O. McKay and his counselors: “I wonder if further consideration should be given to the inclusion of this area [Iceland] in the Danish Mission because of the language, to be made an independent mission later if and when it is secure enough.” [3] Three years later, an opportunity arose which led to the reemergence of missionary activity when a twenty-eight-year-old Latter-day Saint named David B. Timmins arrived with his family to work as the American Consul at the U.S. Embassy in Iceland. Consul Timmins later wrote, “When my wife and I arrived in Reykjavik, Iceland, with our two small sons in early 1958 for my posting to the U.S. Embassy there we immediately found ourselves to be objects of great interest because of the fact that we were Utahns and Mormons. We quickly learned that virtually everyone in Iceland has relatives in Utah—most in the Spanish Fork area.” [4]

Ambassador David B. Timmins (center) while serving as the first branch president in Spain, 1968. Courtesy of LDS Church Archives

Ambassador David B. Timmins (center) while serving as the first branch president in Spain, 1968. Courtesy of LDS Church Archives

Groundwork Laid by Consul Timmins

Timmins further related, “We soon found ourselves invited to any number of receptions, where we were besieged with questions about Utah and the Church. And the local newspaper soon arrived to interview and photograph us and our three children [the third child was born after their arrival] for a front-page article.” [5] Soon thereafter, Timmins was told that the Lutheran bishop of Iceland was teaching a comparative religion course at the University of Iceland and wanted him to discuss Mormon doctrine with his students. Timmins reported,

The Bishop, who proved to be a most distinguished and courteous gentleman, came to our home for a period of one night a week for six or eight weeks while we explored Mormon doctrine in detail, and in the process we became good friends. At the end of our relationship, two years later when we were about to depart Iceland, he told me that he would be pleased to welcome Mormon missionaries back to Iceland (where they had not been for over a hundred years) because he felt we had a message which would improve the moral climate of his countrymen which he considered to be deteriorating. [6]

Not only was Timmins welcomed by this gentle bishop, but he and his wife were invited to spend an evening in the country home of Iceland’s famous Nobel Laureate for Literature, Halldór Kiljan Laxness. Here in the Laxness home, the Timmins also had the opportunity to mingle with other guests who were numbered among Iceland’s aristocracy. During the course of the evening, Laxness invited Timmins privately into his library and related to him what Iceland’s bishop had told Laxness about the Mormon from the embassy. Timmins explains what followed:

It turned out that he was considering a Mormon theme for his next novel and had been put on to me by our mutual acquaintance the Bishop. We talked history and doctrine for about three hours, and at the end of the evening he asked my assistance in arranging contacts and interviews for his intended visit to Utah to gather background for his novel. I thereupon wrote my father, W. Mont Timmins, a bishop, patriarch, and historian, who agreed to make further appointments and escort Mr. Laxness during his visit to Utah. I also wrote a couple of General Authority acquaintances. . . . Mr. Laxness made his trip, later informing me how courteously he’d been received and how delighted he was with his trip. While I’d by that time left Iceland for Harvard University, Mr. Laxness sent me an English language copy of his new book which he called Paradise Regained [Reclaimed]. [7]

Timmins’s assignment as a U.S. diplomat in Iceland ended in 1960; still, the catalytic events he experienced over a period of two brief years proved consequential. After returning to Utah, Timmins explained, “Elder Kimball called my wife and me to his office to inquire about our experiences in Iceland. Within a year, we learned the Danish Mission had commissioned a group of missionaries to take up the Icelandic Bishop’s invitation and a District of the Danish Mission was established in Iceland.” [8] The following year President David O. McKay sent Alvin R. Dyer (Assistant to the Twelve) to Iceland to look into the possibility of sending missionaries to Iceland again. [9]

During the October 1962 General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Elder Alvin R. Dyer, spoke of his recent meeting with the mayor of Reykjavík:

Under the instruction of President McKay, during my term in Europe, I had the experience of going to Iceland and there, after meeting all of the civic authorities that we thought it important to meet, I went into the office of the mayor of Reykjavik, Mayor Hallgrimmson, and he treated us with such courtesy and with such friendliness that I wondered why a man that far off would be so friendly to us in our desire to find out if it would be possible that missionaries could be sent into that land. . . . Mayor Hallgrimmson came to America, unannounced, not as a mayor but as an individual, primarily to visit an uncle who was among those converted. He met and lived with the Mormon people in that area. He observed their manner and way of life and he told of finally coming to Salt Lake City where he met a man who managed a motel, and he said that this man went out of his way to help him. . . . “If these are Latter-day Saints, who so befriended me, why would I not be friendly to you?” And I have often wondered if that man who owned this motel really knew the good that he did when he befriended Mayor Hallgrimmson of Reykjavik, Iceland. [10]

Fact-Finding Mission to Iceland

Just two years later, LDS missionaries Elder P. Bryce Christensen of the Danish Mission and Elder Richard C. Torgerson of the Norwegian Mission teamed up for a visit to Iceland. Their first stop was to Keflavík, where there was a NATO Naval Air station, as well as a small cluster of American Latter-day Saints serving in the military. [11] They were given the assignment to assess the feasibility of sending missionaries to Iceland again. [12] A few days later, Christensen reported his findings to his mission president R. Earl Sorensen, stationed at mission headquarters in Copenhagen: [13]

I feel that four missionaries could have more than enough work to do if they were assigned to Reykjavik. There is an active servicemen’s organization at the Keflavik U.S. Naval Station. We stayed with the leader for the group, and he was very enthused about the possibility of sending missionaries to Iceland. . . . He said he would give the missionaries all the support possible. We met with the servicemen’s group on Sunday, and they were thrilled to have missionaries in attendance. [14]

Christensen suggested, “I think that two experienced missionaries from either Denmark or Norway (both languages are equally effective) should be sent to Iceland first to get things organized. Then I would suggest that two missionaries direct from home be sent up as their companions and learn Icelandic.” [15] Christensen also informed President Sorensen of his meeting with Bishop Sigurbjörn Einarsson, the head of the state Church of Iceland:

We explained the missionary program and Church organization to him, and bore our testimonies. We presented him with a copy of Jesu Kristi Kirke Af Sidsta Dagas Helliges Historia and the Book of Mormon. . . . The Bishop said that it would not be very hard for us to find a place to meet. He said that, of course, he would have to attack any of our teachings which he thought were false. We asked him to read the Book of Mormon before he started attacking. He listened very attentively to us and was very polite. [16]

The young Mormon missionaries also had the privilege of meeting with Mr. Finnbogi Guðmundsson, director of the National Library in Iceland. “He was very friendly and willing to give us any help we needed,” [17] Christensen commented. However, the missionaries’ high expectations of association with the mayor of Reykjavík, with whom Elder Dyer had previously visited, met with disappointment. According to Christensen:

Our visit to the Mayor of Reykjavik, Geir Hallgrimeson, was very disappointing after the great build-up we had received. He was very polite, but he said that he could just barely remember President Dyer’s visit. He said that he had not been in Utah since the visit (as it said in the letter from President Peterson) and that he was not in favor of any of our Church programs because he knew nothing about the Church. Evidently there has been a great deal of misunderstanding on the part of someone. [18]

Christensen summarized the remaining portion of this brief and memorable fact-finding excursion of 1964: “We tracted for a couple of hours, and found exactly the same attitude toward religion as there is found in Denmark and Norway. The people are generally very interested and it won’t be any trouble for missionaries to make appointments and get opportunities to preach the gospel. The big job will get them to see a need for religion.” [19]

Yet another decade elapsed before formal plans were in place for the reestablishment of missionary work among the natives of Iceland.

Preparation of Byron Geslison to Reopen the Iceland Mission

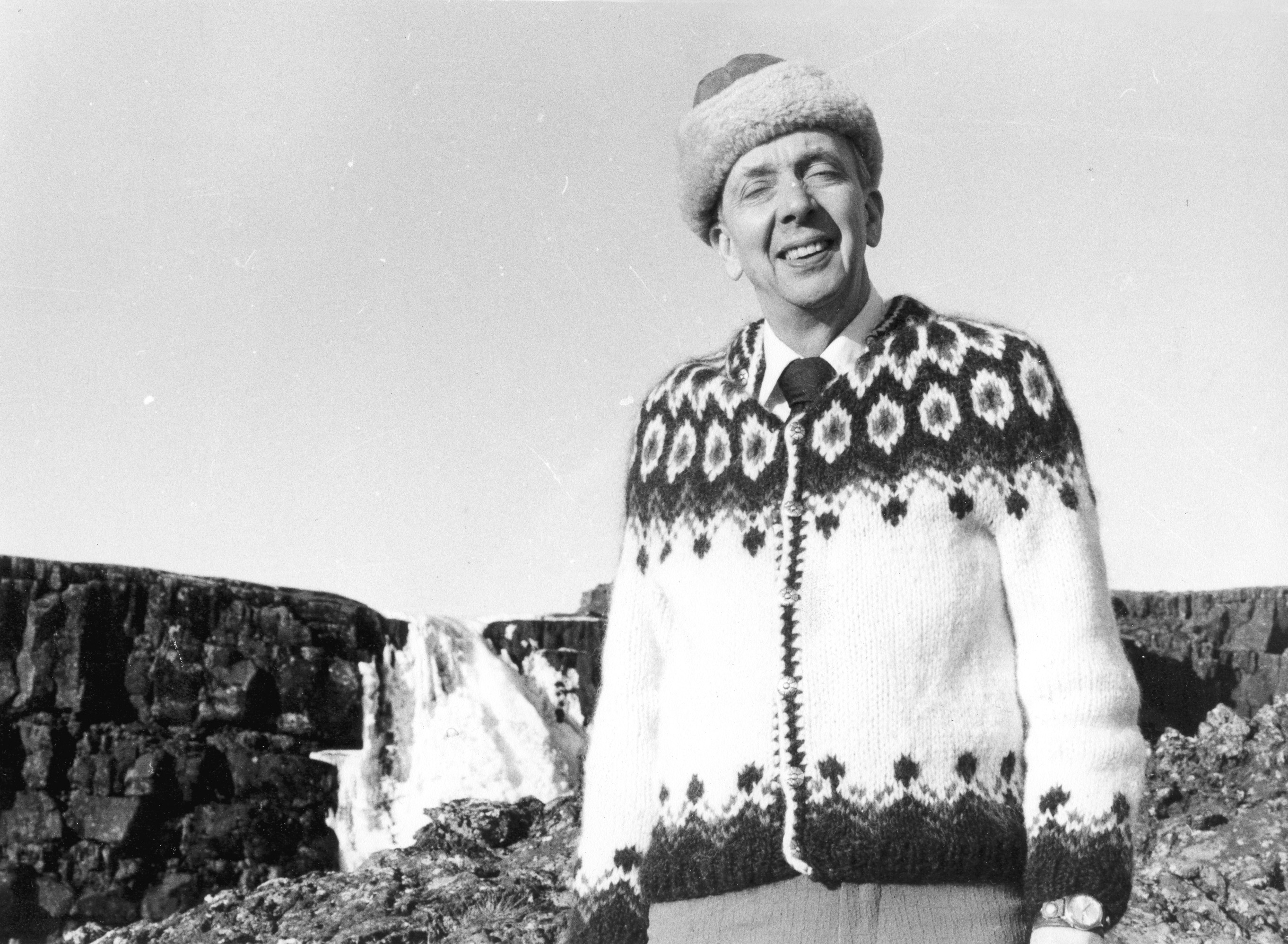

Byron T. Geslison was called to reopen the Icelandic Mission in 1975. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Byron T. Geslison was called to reopen the Icelandic Mission in 1975. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Still it appears that a plan for the reemergence of the Church in Iceland had already been in the making in the very year the LDS Iceland Mission closed. On May 15, 1914, a full-blooded Icelander, Byron T. Geslison, was born in Spanish Fork, Utah. His great-great-grandmother had left Iceland in 1857, bound for Spanish Fork, where she lived among the Latter-day Saints the remainder of her days. Byron’s great-grandmother (Guðný Erasmusdóttir Hafliðasson) left a legacy that infected her posterity with a commitment to the LDS faith as well as a love for their native homeland. [20] Further, when Byron’s Icelandic grandmother (Steinunn Þorsteinsdóttir Geslison) became a widow, she did not want to be alone. Byron recalled:

As soon as I was old enough, she wanted me to stay with her evenings and at night and this did until 10 years old, when she passed away. . . . She spoke mostly Icelandic to me and taught me in the ways of the Icelander. She had a map of Iceland on the wall along with old time pictures of the Westmann Island. I can still see them. . . . She told me of other tales of Iceland and the happenings she remembered. I developed a strong desire to go to this rugged land of my forefathers. [21]

Little did he know as a child that one day he would be the individual asked to reopen LDS missionary work among his countrymen after a six-decade closure of the Iceland Mission.

A specific experience further endeared him to his native homeland. Just before returning from serving as an LDS missionary in the German-Austrian Mission, Byron’s father thought it a good idea for him to ask permission to return home via Iceland, in order to gather genealogy for the family. [22] Permission was granted by Church President Heber J. Grant, who also “requested that I study conditions there as to the advisability of [again] starting missionary work there.” [23]

Byron T. Geslison with his mission president, Roy A. Welker, president of the German-Austrian Mission. On his way home from his mission, Geslison stayed in iceland for a time. Courtesy of Melva Geslison

Byron T. Geslison with his mission president, Roy A. Welker, president of the German-Austrian Mission. On his way home from his mission, Geslison stayed in iceland for a time. Courtesy of Melva Geslison

Byron’s first encounter with his homeland was tumultuous: “A terrible storm came up as we approached the Westmann Islands and all we could do was drop anchor and wait. I got seasick, so sick that I was afraid I was going to die. I surely did not care if I did at that point. When the storm subsided enough they put me in a basket attached to a boom and lowered me into a smaller boat some distance from the ship.” [24] Byron was soon greeted by relatives and spent the summer in Reykjavík living with his cousins. [25]

In Reykjavík, Byron met Sighvatur Brynjólfson, to whom his father had been writing for many years. On his first day in the capital city, Geslison also met a German-speaking Lutheran pastor: “I had the opportunity to speak to him and discuss the religious conditions of Iceland. . . . I told him about the Book of Mormon and he became very nervous and . . . left us on the spot, after a short greeting of departure.” [26]

A Passion is Born

After his first week, Byron was taken on a trip to southern Iceland “to the place where my father’s father and my great-grandparents were born.” This venture included a visit to a summer home, where he lodged for the night with a kind family. The encounter left a memorable impression on him, as indicated by his journal entry that night: “I was amazed at the hospitality of these Icelandic people.” [27] A week after this experience, Byron’s feelings and impressions ran deep. “I feel that I have a mission to perform in the land and that if I continue to hold the Lord’s commandments and be diligent, I shall be able to do it.” He summarized the summer of 1938 in his fatherland: “I feel really like I’m living in heaven.” [28] No wonder his departure was emotionally difficult. He recorded the memorable experience of watching his Icelandic relatives bid him farewell: “They all stood in a little group, some 12 or 13 of them, and when the boat pulled away, they all waved and waved. It was certainly pathetic. I surely had a hard time to keep from breaking down. To stand there and think that maybe I would never see them again was heartbreaking. My only comfort was that I hoped to come back someday.” [29]

Although leaving was difficult, he did not go away empty handed. During that short summer he was able to gather about two thousand names of his ancestors in Reykjavík and in the Westmann Islands. [30] Byron later reminisced, “They took me to many parts of the land and I grew to love it. I met many relatives and made many friends. I met people in important positions and heads of Churches, this was good for my report to President Grant.” [31]

Progress is Slow but Sure

Arriving back in Utah, Byron eagerly gave President Heber J. Grant a very favorable report concerning the potential missionary opportunities in Iceland, but apparently because of the outbreak of World War II, the intention to reestablish missionary efforts there was postponed. It would be nearly two decades later before the Church sent representatives to investigate the possibility of opening Iceland to missionary service.

9 July 1967 Elder Howard W. Hunter, and his wife, and Pres. Jacobson, of the Norwegian Mission arrived at Keflavik International Airport. They were met by Pres. Cupp and several of the [Keflavík] Branch members. They had come to see about opening up the mission field in Iceland. After spending several days with the Officials of Iceland in Reykjavik, they reported to us that they thought it would be very unwise to open the mission field at that time. They did say that they were going to recommend that “The Spoken Word” be translated into Icelandic and be broadcasted over the Icelandic Radio Station as a beginning to opening up the mission field here in Iceland. [32]

Five years later, Elder Loren C. Dunn of the Seventy wrote a letter to the Danish Mission president Grant R. Ipsen, suggesting he travel to Iceland and provide a report of the conditions there. Although President Ipsen had received Elder Dunn’s request around November of 1972, an emergency in the mission postponed the trip. After a six-month lapse, another letter requested that he visit Iceland. About May 1, 1973, Bernard P. Brockbank, president of the International Mission, asked that Ipsen help reorganize the leadership of the Keflavík Branch presidency. Five weeks later, Grant Ipsen and his wife were on their way to Iceland. [33]

Upon arrival the Ipsens met with William Waites, acting branch president of the Keflavík Branch. They reviewed names and addresses of local Icelandic members and visited them in Reykjavík. Their first visit was to a young woman named Þórhildur Einarsdóttir, a convert of eighteen months. Next they visited the Kinski family, consisting of two brothers, Orn and Fálk Kinski, and their mother, Sister Jona Pallisdóttir; all had converted in Denmark before World War II. Ipsen writes, “In 1951, a missionary or a member of the Church came through to Iceland and ordained the two boys . . . Priests in the Priesthood. They [the Kinskis] indicated they had been in the [Church] services a few times from the Keflavik air force base, and then because of tightening of restrictions, they were not allowed on the base, and since that time they had not had any contact with the Church.”

Ipsen concluded his report as follows: “As I see it, the language would be the greatest hindrance. . . . I believe it would be a wonderful opportunity to preach the Gospel. I did not have an antagonistic feeling in the city or in the country. We do have the wonderful little Branch at the Keflavik Air Force Base, plus a nucleus of five or six possibly seven members in Rekavik [sic] or in the surrounding area.” [34]

One LDS District compilation summarizes his visit:

An extensive report of President Ipsen indicated that Iceland would be a suitable place to open active proselyting again. The minutes of the Branch at Keflavik note that the Branch Presidency was reorganized by Danish Mission President Grant R. Ipsen, under the direction of the International Mission President Bernard P. Brockbank. It was noted that on 14 October 1973 there were 44 in attendance at the Sacrament Meeting, a new high. [35]

With this favorable report, the gears were greased to formally reopen missionary work in Iceland. One year later, Church officials contacted the Geslison family.

The Geslison Family Called and Arrive in Iceland

Byron T. Geslison recorded in his journal the initial contact made by one of the Church General Authorities in the late fall of 1974:

Brother Rictor [Elder Hartman Rector Jr.] first called while I was home to lunch on Tuesday Nov. 19, 1974. Said he wanted names of possible couples to Iceland. When I could come up with none he asked about us; Melva and me, as if that was his question from the first. He asked what would prevent our going. I respon[d]ed that I was rusty in the Icelandic language and that we had two sons out in the mission field in the Far East of whom we had a responsibility. [36]

In overcoming the first obstacle, Elder Rector countered, “You can brush up, can’t you?” Byron responded that he thought he could. “I told him that given a little time I might come up with some better suggestions than us. He said to call him in a few days or he would get in touch with me. For the next week I had some unusual feelings. I . . . couldn’t get it off my mind. I knew we had a destiny in Iceland.” [37]

About a week later, Elder Rector called and Byron reiterated his concern for the twins. Elder Rector empathized, “The Brethren were concerned about that also.” Geslison noted, “I told him I could come up with no other names who fit the conditions called for. He said he would talk further with the Brethren and would get back to me.” Byron wrote in his diary, “We were to go back to Omaha for Christmas. . . . On the way back I had an impression of a definite call and that President Kimball & the first Presidency & others were involved in a discussion of us & Iceland & that we would be sent up to open Iceland to missionary work with Dave and Dan going with us. That was Monday Dec 30.” [38] A week later, Byron and Melva were called into the office of their local bishop who informed them that he had received a call from Elder Rector: “Brother Rector had been requested by President Kimball to hurry the work in Iceland & not to delay in getting us called and up there; that the twins would go with us.” [39]

An Obstacle Overcome

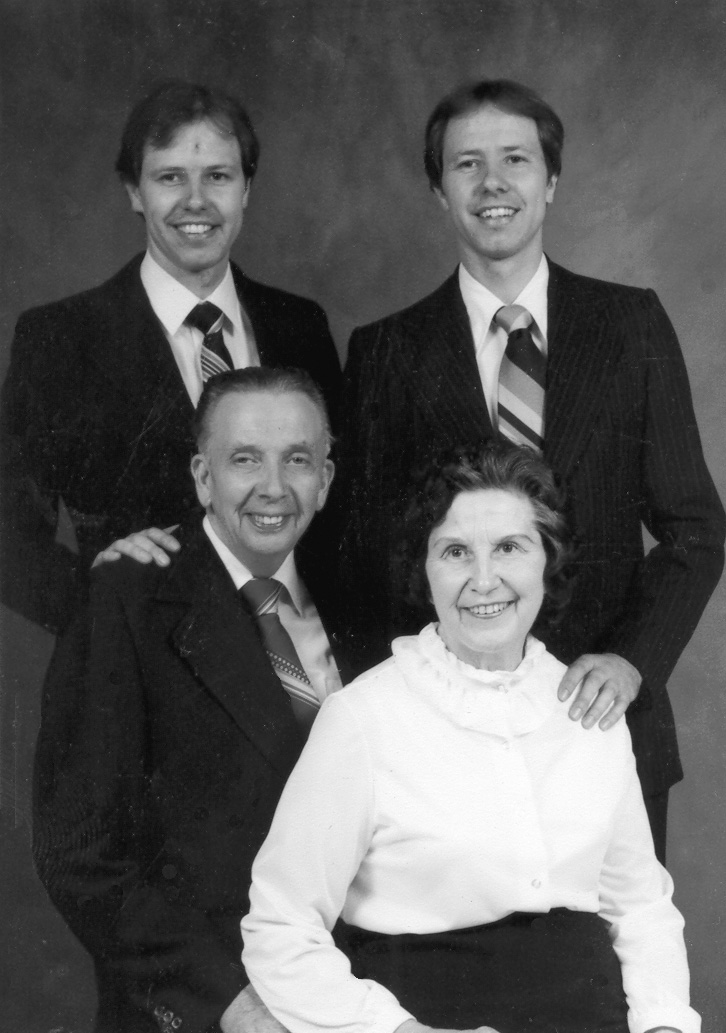

At the time of the call, the Geslisons’ twin sons, David and Daniel, would soon be returning from serving two-year, full-time missions for the Church, David in Korea and Daniel in Japan. Byron and Melva were naturally concerned that their sons were returning at the same time they would be leaving for the mission field. The problem was solved when President Spencer W. Kimball was impressed that the boys should immediately be called to serve another full-time mission to accompany their parents in Iceland. [40] The day after his bishop issued the call, Byron wrote this letter to both sons, dated January 8, 1975:

I hope what I am about to say will in NO WAY effect the remainder of your mission only for the better and I think it will have the effect to bring you to even greater dedication and devotion and that you will end your missions there in a blaze of glory. We knew you would do that all along. What you did not know however is that, you probably will not spend much time if any time at home for another possibly two years more or less. The First Presidency is about to call your mother and me to Iceland and they have approved that you and your brother go with us or meet us there whichever way it works out best after we get the official call. . . . We hope that you will not be too shocked by this and that you can [be] reconciled to changing whatever plans you have been making. [41]

Both twins were delighted with the news, excited to serve a mission with their parents and each other. As children, these twins had dreamed of the opportunity to one day serve a full-time mission together, and now, unexpectedly, their wishes could be realized. They returned to Spanish Fork on March 19, 1975. In less than three weeks they were delivering their mission reports and mission farewells the same day (April 6), and by April 18, 1975, the Geslison family had arrived in Iceland. [42]

Briefings and Recommendations

Before the twins’ return and the flight to Iceland, Byron and Melva received instruction from Church leaders in Salt Lake City on February 13. Byron recorded the contents of this important meeting: “At 4:00pm we met with Elder Rector & Elder Bernard Brockbank who presides over the international mission. . . . We discussed timing, twins, contacts with Icelandic Associates & the Icelandic community in Spanish Fork. Needs in the way of printed materials. The Book of Mormon being translated. Home Evening materials etc.” [43]

Photo of the Geslison family. Courtesy of the Geslison family

Photo of the Geslison family. Courtesy of the Geslison family

Byron was asked “to go thru the old Icelandic tracts and materials in the Church Historian’s office which might be used on a temporary basis, since there was no written material in Icelandic.” Geslison therefore “selected fourteen tracts which he felt would be useful in the work while waiting for the first official tracts to be printed, and the brethren agreed to make fifty copies of each and send to Iceland. . . . It was felt, because of its [the Iceland Mission’s] peculiar problems, that it should be operated . . . as an emerging or miniature mission.” [44]

During their February meeting with Church leaders, Geslison made several suggestions regarding moving the work forward in Iceland: “We also inquired if young men of Icelandic descent might be called later as missionaries. They thought that was a good idea. I made the suggestion that boys of Icelandic descent could have their Bishops and Stake Presidents put their names on the missionary recommendation form ‘Of Icelandic Descent.’” Byron further recommended that “people of Icelandic descent . . . go the second mile and help with Icelandic missionary work by funneling their money thru Sp. Fork Utah Stake which could go into an ‘Icelandic Mission Fund.’” [45]

Less than two months later, Byron and his family discovered a second-mile effort already performed by the Saints of his local area: the twins gave their combined mission reports and farewell addresses in a Spanish Fork chapel filled to overflowing with a congregation of 600 to 800. After this April 6 meeting concluded, Byron wrote, “We talked to many after & many came to the house. We had so many offers to help & so much given us that when . . . [donations were] counted up before we left, it was nearly $2500.00.” [46] Less than two weeks later, the Geslisons were on their way to Iceland. [47]

A Hospitable Welcome

Byron recorded his first impressions as his family landed in Iceland to embark on their mission: “At the Keplavik Airbase we were met by Pres. Broadbent, Bentley & Curtis the Branch Presidency of Keplavik. They were so glad to see us & helped us so much. . . . Brother Curtis brought us to #17 Falkagata to be our home for several weeks. We met Bro Payne (Dr. David Payne) & he warmly welcomed us.” [48]

Upon their arrival in the mission field, they found only one fully active member of the Church in the area: “Thorsteinn Jonsson, a fisherman who had been baptized about a year before and had been attending meetings at Keflavik Air Base, along with an occasional investigator.” [49] Þorsteinn proved to be a great blessing to the Geslisons, wearing himself out in providing for their needs. For example, a few days after their arrival Byron wrote, “Bro Jonsson brought us fish and blankets . . .—6 of them.” The following month, “Thorsteinn came & brought fish & lamb.” [50] Further, “Friday June 27th Thorsteinn comes from sea and begins looking for a place for us and offers us his place for as long as is needed.” [51]

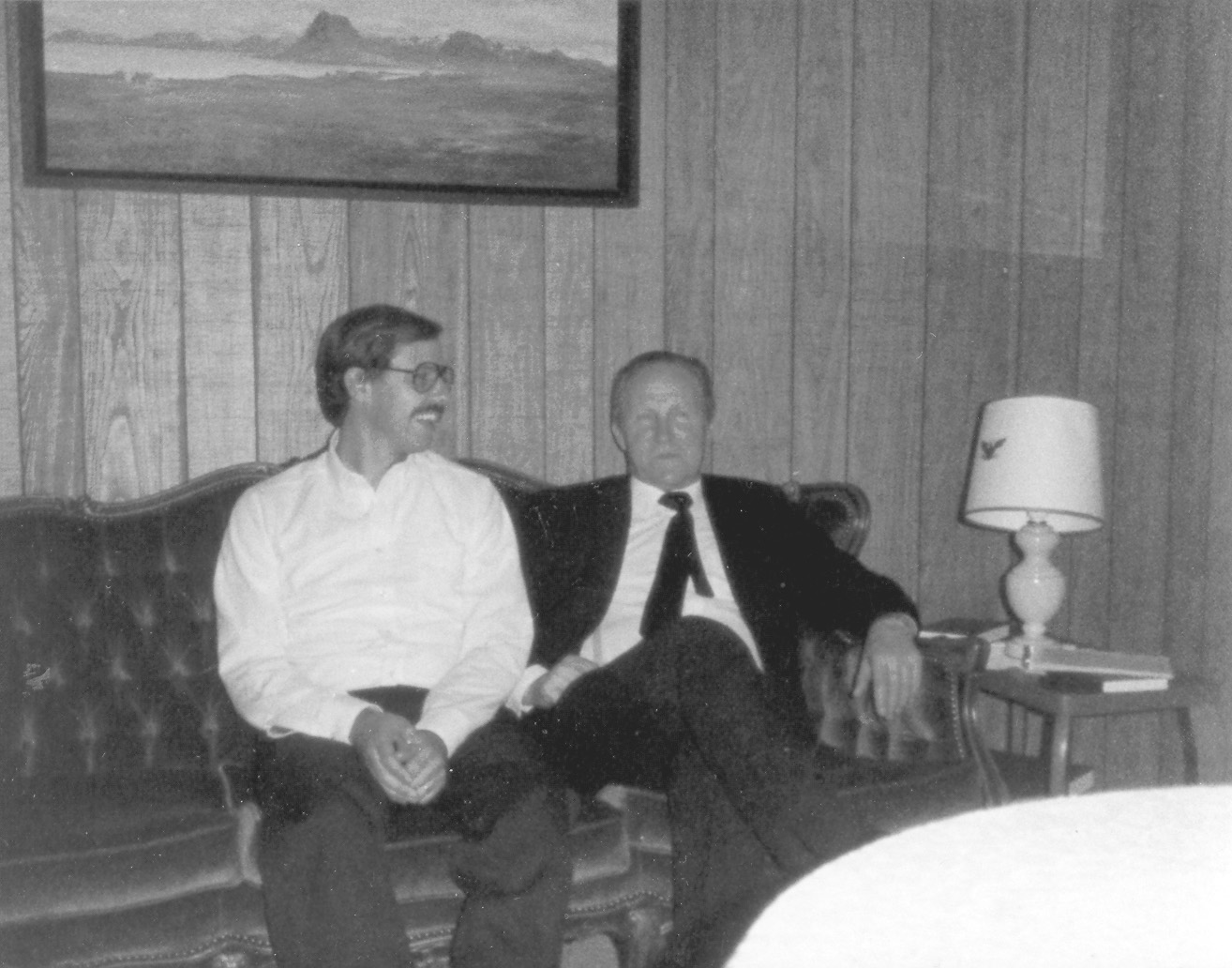

Daniel Geslison (left) visiting Þorsteinn Jónsson, who was the only fully active member of the Church when the Geslisons arrived in Iceland. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Daniel Geslison (left) visiting Þorsteinn Jónsson, who was the only fully active member of the Church when the Geslisons arrived in Iceland. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

The Geslisons’ initial living arrangements quickly changed due to Dr. Payne and his family’s return to Utah and a rental agreement that expired with no option for renewal. As a result, they struggled for several months to find other affordable living accommodations. [52] Knowing of their plight, Þorsteinn gladly inconvenienced himself by giving up his apartment and living on his fishing boat for a time. The family soon learned that they should not tell Þorsteinn anything they were lacking, for he would make great sacrifices to assure that their needs were met. In reminiscing, the Geslisons all agreed that no one helped them more than Þorsteinn Jónsson. [53]

Opportunities for Growth Arise

The challenges at first seemed arduous. Less than two weeks after reaching Iceland, Byron recorded the visit of President Grant Ipsen and his wife, whom he described as “most gracious & wonderful.” During their short stay, Grant Ipsen, president of the Denmark Copenhagen Mission, conducted ecclesiastical business during a branch conference. Geslison recorded on May 1, 1975: “Pres. Ibsen presented the proposition that Reykjavik be taken from the International Mission & placed in the Denmark Copenhagen Mission. This was unanimous. Pres. Ibsen then presented Byron T. Geslison as the District President of the Iceland District of that mission called by the prophet of God. This was unanimous.” Such a transaction caused Byron to write, “I felt the weight of this great assignment now to go forth & open Iceland to missionary work.” [54]

Byron also recalled, “Our task when we arrived, seemed rather formidable when we realized that we had no materials to work with, no tracts, no scripture, except the Bible, no building, no budget, no adequate housing, and no members to meet with, excepting the Servicemen’s Branch on NATO base.” [55] The weather and lack of missionary successes sometimes discouraged the twins. David remembered, “Dad was always a stalwart of faith.” [56]

Adjustments to miscellaneous costs were an immediate concern. Just after their arrival, Byron wrote, “We went to the store & I gave Melva Kr. [Kroner] 5000.00 & she thought she was rich but it took most of it for a few groceries and it was all gone in bus fare etc.” [57] Humor found its place in helping to deflect difficulties, such as when “Melva had bought a lamb leg smoked, but it turned out to be a lambs head.” [58]

Melva Geslison. Courtesy of Daniel Geslison

Melva Geslison. Courtesy of Daniel Geslison

One technique Melva used to deal with such incidents was to write parodies to lighten the heaviness of disappointment that occasionally set in. One of a number of favorites faithfully recorded was titled “Our Ravings”:

Once upon a winter dreary

As we tracted weak and weary

Over the hardened lava roads

With feet so SoreWe started gently tapping

And increased to timid rapping

Rapping on the íbúð [apartment] door. . . .The door was opened slightly

And our spirit lifted lightly

We said; “We’re the Mormons”

The door closed and nothing moreAnd we went on our way undaunted

Tho to die we really wanted,

Just to die and nothing more. . . .Soon our hunger started growing

And our weariness was showing

And we headed for home and food galore.We started really hoping

Sister Pres. had done her shopping

And we visioned all the treats

That were in store.But Alas our hope was ended

As to each his plate was handed

Only fish and nothing more—[59]

Challenge of Learning the Language

One of the immediate difficulties facing the Geslisons was learning Icelandic, reputedly one of the most challenging of languages to master. But Byron maintained, “The twins learned it surprisingly fast and were giving Sunday School lessons in Icelandic in a matter of a few weeks, adapting the missionary discussions and augmenting them as best they could.” [60] Soon Byron requested that other missionaries be sent to assist in the work:

In July I wrote the Missionary Committee, as I had been instructed to do when I felt we would be ready for more missionaries. I learned sometime later that four Elders would arrive in September. It was thought that since the Icelandic language was so difficult and since good language is so important in missionary work, that we would enroll the Elders in the University of Iceland for a ten-week . . . Icelandic grammar course. The eight of us took the course and it proved to be an excellent thing to do. The group came through the course very well and it set a high standard for language excellence that was to become a goal for all missionaries in Iceland. [61]

An Opportunity to Promote Favorable Public Opinion

Another opportunity that worked to their advantage presented itself when Byron was invited to present his religious views on national television on August 30, 1975. Byron recalled that the interviewer, Mr. Guðnason, “thought it best to conduct the interview in English with some Icelandic at the end of the interview.” He also noted, “I felt satisfied with it and felt the Lord was with me & would use it to help in His work here. The five minutes or so went rapidly. He asked if we weren’t discouraged being here or coming here when the early missionaries received so much persecution & because of the bad manner in which they had been received.” Geslison responded, “I told him—no—that on the contrary we were very incouraged [sic] and enthusiastic & that we didn’t feel that we had been received earlier so badly when or since about 200 families joined the Church.”

He also fielded a number of questions regarding Latter-Saint doctrine, which included an explanation of how a belief in modern-day revelation, as well as how modern-day prophets and apostles made all the difference. Guðnason said he asked “how we expected to carry out our work & I told him the rest in Icelandic that missionaries were coming and they would work among the people. Then I bore my testimony.” [62]

The interview was well received by the Icelanders, and as a result doctrinal misunderstandings were clarified. Byron was of the opinion that the interview was a “fair and factual report which did us much good.” Several newspapers reported the interview, thus aiding the missionaries with their proselytizing. [63] One of the missionary twins, David Geslison, recalled that his father’s appearance on television helped generate discussion and open up more doors for proselytizing. [64]

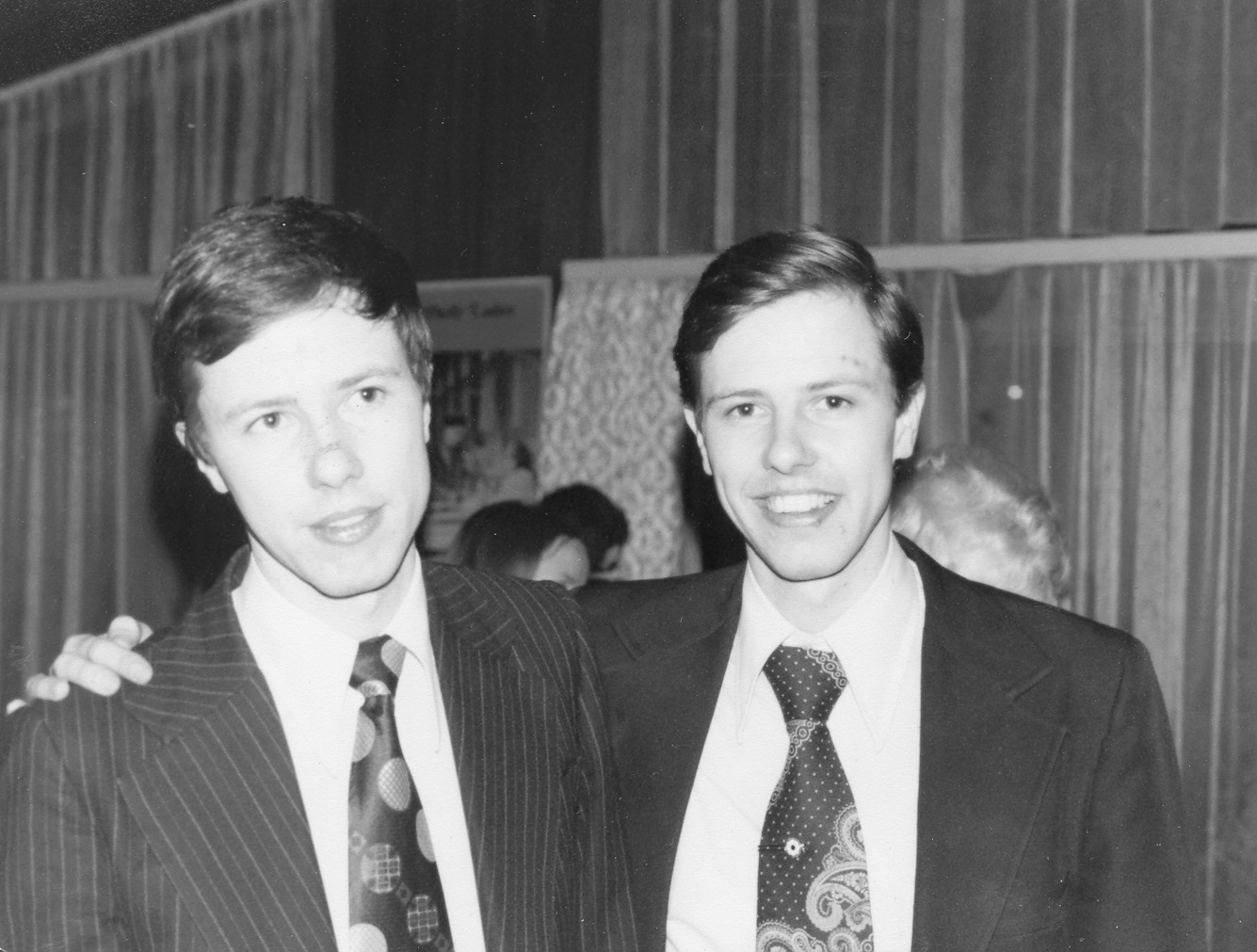

David (left) and Daniel Geslison quickly picked up the language after arriving in Iceland. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

David (left) and Daniel Geslison quickly picked up the language after arriving in Iceland. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

One very important contact of the Geslisons was with the influential bishop of Iceland. “The Bishop of Iceland has always been friendly since the first visit and has left his door open. He has a copy of all of our tracts, the Book of Mormon and Theodore Dedrickson’s book. He has helped us at different times that we had need of his help. His is one of the most important office in Iceland, since he is head of the State Church and also has political influence.” [65]

Iceland’s president entertained many visits from the Latter-day Saint missionaries. Geslison reported, “He has read three books on the archaeology of the Book of Mormon and is now reading A Marvelous Work and a Wonder. He was an archaeology professor at the University of Iceland before coming to this high office. He is especially impressed with the microfilming project of the Church. . . . His door has always been open to me.” [66]

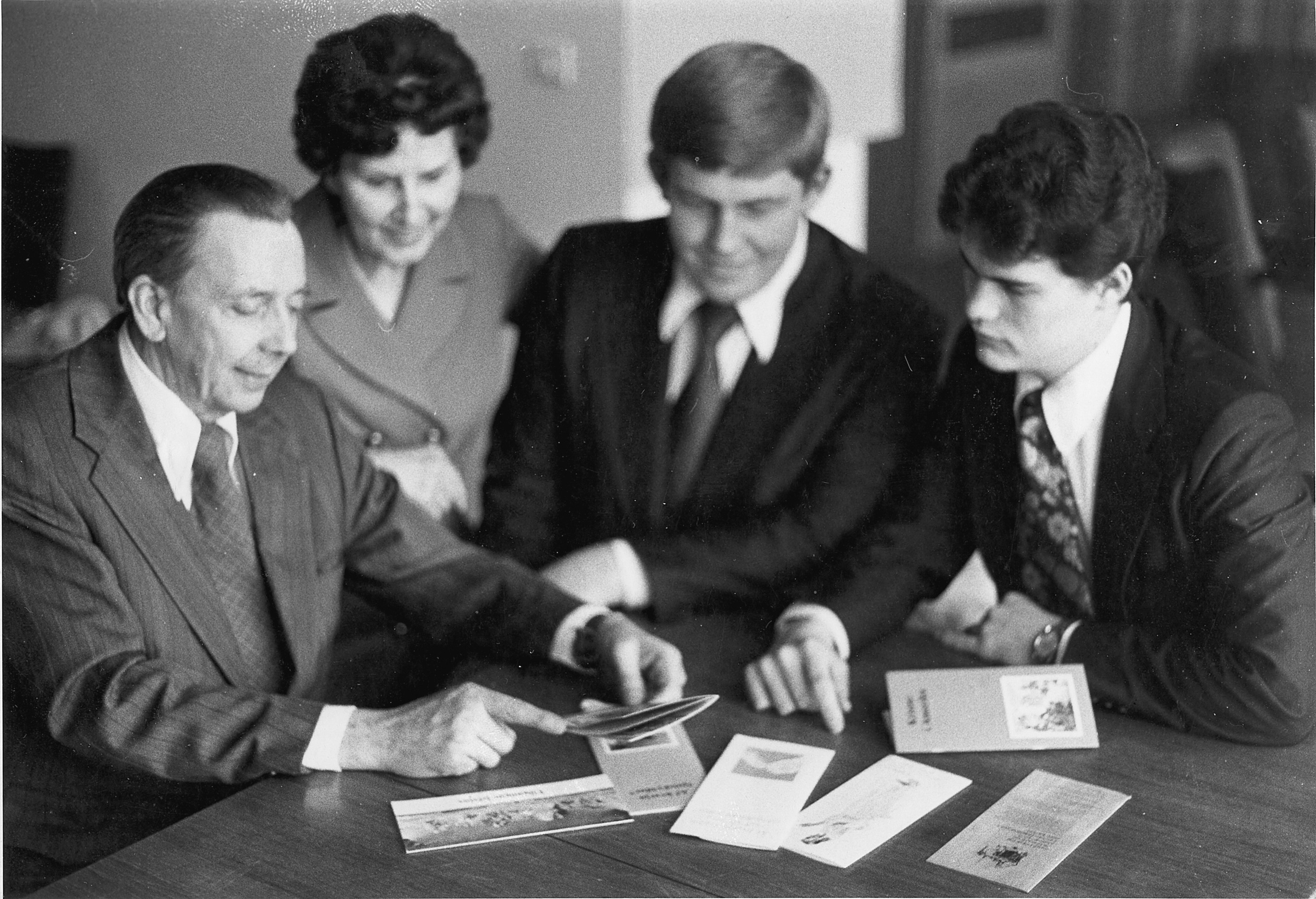

Byron and Melva Geslison, David Dedrickson, and Ty Erickson look at newly translated Icelandic missionary tracts, 1977. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Byron and Melva Geslison, David Dedrickson, and Ty Erickson look at newly translated Icelandic missionary tracts, 1977. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Translation Work Proceeds

One of the next great challenges for the new mission president was to obtain written material prepared to aid in missionary work. Upon arriving in Iceland, Byron noted, “There were no missionary discussions, no tracts, no film strips, no literature at all excepting old tracts.” Thus one of the first aims was to hire a translator. Byron found a competent one in Hersteinn Pálsson, former editor of the local newspaper Vísir. Pálsson first began work on the needed missionary discussions, and tracts soon followed. [67] Þorsteinn Jónsson also volunteered to help the Geslisons with the translation work, as well as with their Icelandic pronunciation.

Sveinbjörg Guðmundsdóttir (above) translated most of the Book of Mormon into Icelandic, 1976. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Sveinbjörg Guðmundsdóttir (above) translated most of the Book of Mormon into Icelandic, 1976. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

After being in this new country for just a short time, Daniel Geslison recorded in his journal a special experience. He had spent the week memorizing the Joseph Smith story, which Þorsteinn Jónsson had translated from an English missionary tract into Icelandic. On Sunday, April 27, 1975, Daniel stood in a Sunday School class and told the assembled group that he was going to share the Joseph Smith story in Icelandic. He made the presentation without a flaw, an act that moved his new friend and tutor, Þorsteinn, to tears. [68]

In addition to the effective missionary tracks, it was imperative that the Geslisons have a translation of the Book of Mormon. Byron reports: “After several unsuccessful attempts to get the translation of the Book of Mormon underway, a man was hired in August [1977] by the name of Ulfur Ragnarsson.” Sveinbjörg Guðmundsdóttir had been assigned to supervise this translation and was an excellent resource. [69] Like Þorsteinn Jónsson, Sveinbjörg proved to be a great blessing to the work. She was initially contacted by Elder Brad Bearnson and Elder Blake Hansen, the two additional missionaries who had joined the Geslisons by the fall of 1975. [70] In his journal dated May 2, 1976, Daniel Geslison recorded an impressive testimony that Sveinbjörg, not yet a member of the LDS faith, offered, which greatly moved all present: “It was at first a regular meeting and then Sveinbjörg stood up—and bore the most spiritual testimony that I have heard from a nonmember—She said I’m not a Mormon ‘not yet’—Then she bore testimony. . . . I can’t explain in words how wonderful the spirit was in that meeting. There was not a dry eye in the whole audience.” [71] Her testimony and example left an impact on many.

Production of Proselytizing Media

Another proselytizing tool which needed attention was that of filmstrips. Byron recalled:

At the beginning we used the English and Danish filmstrips which were available. It was readily apparent that to be effective we needed filmstrips in Icelandic, for since some people understood some English and Danish, yet few understood in sufficient depth to get the messages of the filmstrips. . . . One morning I felt especially impressed to visit the radio station. I had met the gentlemen in charge of the national radio and television and he had been friendly and seemed to have some interest in us. On the stairs I met Peter Peterson, who was one of the announcers on radio and in charge of some radio programming. He expressed himself to the effect that he felt bad that the earlier missionaries had been treated so shamefully and he didn’t want that to happen this time and he wanted to do what he could to help us out. I offered him the use of some Tabernacle Choir tapes I had and asked him if we could work out something so that we could use their studios and technical help to produce some filmstrips for our work. He took me to the man who programmed the studio and we set up a series of appointments.[72]

This process led to the successful production of sixteen filmstrips by the fall of 1976. To ensure the best, given their resources, Byron “secured the professional services of Iceland’s ‘golden voice,’ Hersteinn Pálsson, and used members and missionaries for the various parts needed.” Byron reported their effectiveness in “serving a great purpose in helping carry our message to the Icelandic people and have helped to build the morale of the missionaries and members a great deal.” He further recognized that the filmstrips had been used effectively in public schools and open house programs, as well as other Church functions. [73]

Church Auxiliaries Established

By August of 1976, two small ecclesiastical units known as branches were functioning in Iceland, one on the NATO base in Keflavík and the other in Reykjavík. Since the arrival of the Geslison family, the Keflavík Branch had increased to about 130 members of both American and Icelandic converts. [74] Church auxiliaries for young men and young women were soon organized in the Reykjavík Branch. The women’s organization (Relief Society) was also formed, Sister Melva Geslison acting as president. [75] Melva was influential in lifting the Saints at most meetings with the music she played on an old pump organ, transported from Utah through funds donated by local Saints of Spanish Fork, Utah. [76]

Finding a place to have Church meetings in Reykjavík was difficult. As his first mission drew to a close in December 1977, Byron reported:

Up to recently we have rented a home with an extra large living room and have held all of our meetings there. . . . Just recently we were miraculously able to secure a hall with three adjacent spaces for classrooms. This facility is in the best part of Reykjavik on the Main street where the center of activity is. . . . The missionaries can use it in many ways to improve missionary work. It gives us permanency & status because of the excellent location and type of facility. It will give us excellent exposure, since most everyone frequents this part of town. It has done much to give the members a feeling of pride in their facility. . . . Investigators will feel much freer to attend our meetings now than when they were held in the home. It will give us an additional reason to become recognized by the government. One of the requirements is to show proof of permanency. [77]

Opposition seemed to follow closely on the heels of each small success. In late December, Byron explained: “The main opposition directed against the Church at the present is coming from a quarterly publication which has connections with the State church. The Editor has told us his goal is to drive us out of Iceland as was done many years ago. He has written two bad articles about us. He permitted us to answer his first article but has said he will not permit this again.” Further, it was reported that two brothers who had once been LDS Church members were now doing everything possible to hurt the Church and were also supporting the editor in his opposition to the Latter-day Saint cause. But Byron Geslison remained optimistic, believing that the opposition would in fact strengthen and unify the local congregation of Saints. [78]

Iceland Dedicated for the Preaching of the Gospel

One important event that helped to bring permanency to the Icelandic Saints was the dedication of the land for the preaching of the gospel. Byron recalled:

In the summer of 1977 we received word that Elder [Joseph B.] Wirthlin had been assigned by the Brethren to come to Iceland and dedicate the land. Elder Wirthlin came in September 1977. A Conference was held and in connection with it the dedication took place. Elder Wirthlin sent word to select a site, preferably on a hill overlooking Reykjavik. Oskahlid, a hill in the south part of the city overlooking Reykjavik, was recommended. Elder Wirthlin was pleased with this site. . . .The dedication was to take place between the morning and afternoon sessions of Conference. The weather was cold and storms were about the area and the weather was very threatening. . . . Elder Wirthlin and I decided on holding it inside and so I announced it. The members were quite unhappy with this decision and so expressed themselves. Trudy, a teenage girl from Keflavik Branch, said that it would not rain, that we had made an appointment with the Lord and He wouldn’t let it rain. Brother Wirthlin and I consulted and decided to go on the hill for the dedication. . . . [We] met on the hill and the impressive and inspiring dedication took place. It did not rain and it proved to be a beautiful and a great experience for all. It was truly a great historical milestone in the history of missionary work in Iceland. [79]

Among other things, Elder Wirthlin said, “I dedicate the land of Iceland for the preaching of the Gospel and for the establishment of Thy Church and Kingdom on this land. I bless this people that there may be many wonderful sons and daughters of Thee who will recognize the truth and embrace the Gospel.” Elder Wirthlin was also mindful of the leaders of the country: “I invoke my blessing upon the government. Through the principles of the gospel may they be inspired so that peace may always prevail in this land.” Finally, he blessed the elements of this unique country: “I invoke Thy blessing of this day on this beautiful land, which is a land of beautiful lakes and tall mountains covered with eternal glaciers. Wilt thou bless it abundantly? May it produce the necessities of life for this people.” [80]

Although the wheels of the Church would roll slowly in Iceland, the message of Mormonism would steadily go forth. And though the Latter-day Saints felt it was God’s decree that the good people of Iceland be given the opportunity to hear the fullness of His saving truths, it was the meek and humble who made it all happen. The Geslison family was the right tool at the right time for the job at hand. Gentle but determined, meek yet wise, they sought for divine direction day after day to move the work forward. They endured discouragement and seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Yet they endured. Who can enumerate the incalculable blessing these years of missionary service wrought upon the family, let alone the lives they influenced for good in Iceland? Perhaps the gratitude and expressions of commendations which they so deserve will be insignificant compared to the rewards and honor heaped upon them in a future day.

Notes

[1] Assistant Church historian Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing Company, 1941), writes, “Iceland was a part of the Scandinavian Mission from 1851 to 1894, when it was transferred to the British Mission. A few years later it was listed as a separate mission which was continued until 1914. In 1930 the few local Saints on Iceland belonged to the Danish Mission. For several years no Elders from Zion [Utah] were sent to Iceland, but in 1930 two Elders, James C. Ostegar and F. Lynn Michelsen, labored there for a few months.” Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission,” 129–30, suggests, “Failure to establish a strong organization in Iceland was due to a combination of things: (1) the great distance which separates Iceland from Church headquarters in Copenhagen, (2) languages difference between Iceland and Denmark, (3) opposition, and (4) emigration.”

[2] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), typescript in possession of Melva Geslison, August 28, 1938 (p. 341), notes that upon arrival in Copenhagen, Elder Geslison (who had been serving in the German Austrian Mission) “went out to Sunday School and met missionaries and Pres. Garff. They told me that they had missionaries in the summer of 1930, but they called them out, thinking it was not of any use.”

[3] Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission,” 131. In a talk titled “Icelandic Settlement in Utah 100 Years Old,” given in 1955 at the centennial anniversary of the Icelandic settlement in Spanish Fork, Petur Eggerz, counselor of the legislation of Iceland, stated: “Two years ago Utah’s Genealogical Society sent welcome representatives to Iceland. They took microfilms of all books and documents in possession of the National Archives in Iceland.” Thus, the microfilming of these records in 1953 may also be viewed as part of the preparation for Iceland to again receive missionaries.

[4] David B. Timmins, “The Second Beginning of the Church in Iceland,” unpublished document in the author’s possession, 1. The author wishes to express appreciation to Clark T. Thorstenson, who later served as the Icelandic Consul to the western United States, for allowing him to have a copy of this manuscript, which is also located at the Church Archives in Salt Lake City. In a manuscript in the files of the LDS Icelandic Branch in the Reykjavík region titled “A Brief History of the Icelandic Branch,” comp. Donald R. Knight, 1, the very first entry to a written Church record since the closure of the mission of 1914 states the following for the date of May 3, 1959: “Kenneth Fowles, Elder, ‘presiding and conducting’ First meeting held in Reykjavik at the home of Brother and Sister Timmins. Bro. Timmins is listed as employed at the American Embassy.” The second entry, dated May 6, 1959, notes: “Wednesday evening meeting at Keflavik Naval Air Station. The pattern was get for regular Sunday and Wednesday meetings which continued unbroken until 2 Nov 1960. During this time attendance at the meetings ranged from 3 to 12.” Page 2 of this document indicates that these assorted notes were compiled by Donald R. Knight, September 16, 1972.

[5] Timmins, “The Second Beginning of the Church in Iceland,” 1.

[6] Timmins, “The Second Beginning of the Church in Iceland,” 1.

[7] Timmins, “The Second Beginning of the Church in Iceland,” 2. The novel Paradise Reclaimed (Timmins misspoke; the title is not Paradise Regained), published in 1962, focuses on an LDS convert who immigrated to Spanish Fork and later returned to Iceland, where Laxness asserts he reclaimed paradise. This novel is the most well-known book concerning Latter-day Saints in all of Iceland. Though well written, unfortunately this novel presents a picture of Mormonism that is not altogether accurate. In an interview in the winter of 2000 with the late Byron Geslison, who served several missions to Iceland, Byron informed the author that one evening when Geslison was in the home of Laxness, the famous poet admitted that he did take poetic license in relating the history of the Latter-day Saints. Geslison further noted, “Halldor Kiljan Laxness, Iceland’s Nobel Prize winner in Literature, has received us several times and has much of our literature. He and his wife have offered to help us and there is a letter on file from him stating his desire to help us where he can” (Byron T. Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 17, in author’s possession).

[8] Timmins, “The Second Beginning of the Church in Iceland,” 2.

[9] Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission,” 131. For the interesting story of events leading up to missionary work again opening up in Iceland, see also the 1973 typescript of interview of Grant Ruel Ipsen (president of the Danish Mission), Church Archives, 1–6.

[10] Alvin R. Dyer, in Conference Report, October 5, 1962 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), 12–13.

[11] Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission,” 214, notes, “On April 1, 1920, the Norwegian Mission was organized as an independent mission as it was separated from Denmark”—in other words, from the Danish Mission.

[12] In a November 20, 1964, letter written from Oslo, Norway, by Dean A. Peterson, Norwegian Mission president, to Geir Hallgrímsson, mayor of Reykjavík, President Peterson informed the mayor that two young Americans were going to be visiting him from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Peterson wrote, “They are Mr. Richard C. Torgerson and Mr. P. Bryce Christensen. Mr. Torgerson has been in Norway for the past two and a half years and Mr. Christensen has been in Denmark for the same length of time. The purpose of their trip as representatives for the Church, is to obtain information for President [Ezra Taft] Benson in the possible consideration of sending missionaries to labor in Iceland.” President Benson was at this time a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and also the President of the European Mission. A copy of this letter was faxed to me by Bryce Christensen on February 22, 2000. The author expresses appreciation to Bryce for his help. It also seems reasonable to suppose that one missionary was sent from each mission as the question may have arisen as to which mission Iceland would fit better in: the Danish Mission or the Norwegian Mission.

[13] Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission,” 214, indicates that R. Earl Sorensen began serving as the president of the Danish Mission in 1963.

[14] Bryce Christensen to R. Earl Sorensen, December 9, 1964, 1, letter in author’s possession. Christensen, 3, also points out that the LDS group leader for Iceland was “Ssgt. Billy N. Jensen, USAF.” The following year, “A Brief History History of the Icelandic Branch,” comp. Donald R. Knight, Reykjavík Branch Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 11, notes, “12 Dec. 1965 Good news has been given our fine group. We are now a branch in the British Stake (Mission). Our Branch President Billy Jensen, will go to London next month to make the final arrangements. We are a fast growing group.” Six months later this same Church record notes, 12, “12 June 1966 Last Sunday night the branch held a fairwell for Billy and Marilyn Jensen and their family. Billy had been a tool in the Lords hand in establishing the branch in Iceland. . . . Last month Brother Leonard Jensen was sustained and went to London and was set apart as Branch President and Pres. Billy Jensen was released as Branch President.” In a separate one-page manuscript titled “Relief Society in the Icelandic Branch,” apparently compiled from the records of the LDS Icelandic Reykjavík Branch, 1, an extract from a Relief Society meeting notes for the date of January 25, 1966, “Icelandic Branch was organized on 16 Jan 1966 after Brother Billy N. Jensen went to London to be called to the position of Branch President under [the] British Mission and given authority to organize the Branch, IT WAS THE FIRST TO BE ORGANIZED SINCE 1947 IN ICELAND.” Apparently this refers to the Relief Society organized on the Keflavík NATO base, largely made up of Americans, and not an Icelandic branch. The 1947 reference is very interesting, but thus far no information has been found to provide more details. In another one-page manuscript titled “Primary in the Icelandic Branch,” which contains extracts apparently compiled from LDS Reykjavík Branch records, 1, one extract notes, “Primary for 65–66 had 5 teachers and officers and there were 7 LDS and 1 non-member children. . . . The non-member child apparently was baptized because the later enrollment later became 8 LDS.”

[15] Christensen to Sorensen, December 9, 1964, 3.

[16] Christensen to Sorensen, December 9, 1964, 2.

[17] Christensen to Sorensen, December 9, 1964, 3.

[18] Christensen to Sorensen, December 9, 1964, 3–4.

[19] Christensen to Sorensen, December 9, 1964, 4.

[20] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 85–86, wrote that Gudný “was born September 6, 1794, in Kirkulaekur, Teigur, Rangarvalla, Iceland, the daughter of Erasmus Eyjolfsson and Katrine Asgeirsson. She was married to Arni Haflidasson on October 4, 1828. They had six children, but only two lived to maturity. Her husband was drowned while fishing in 1847. Gudny then worked in a fish-packing plant.” Gudný joined the LDS Church and left Iceland in 1857. However, she did not arrive in Spanish Fork until 1859 because the small Icelandic group she emigrated with stopped in Fairfield, Iowa, in order to obtain the funds needed to proceed to Utah (see Mission History of the Icelandic Mission, 1857). According to David B. Geslison, she was known as “Old Gudny,” and it was said that she did not walk across the plains with her handcart, but rather that she “ran across the plains” (interview of David, Daniel, and Melva Geslison by Fred E. Woods, May 22, 2005 in Spanish Fork, Utah). Allred, 86, further notes, “She died June 14, 1888, and was buried in Spanish Fork City Cemetery.”

[21] “Autobiography of Byron T. Geslison,” 1. This is really an unpublished autobiographical sketch a copy of in author’s possession. The author expresses appreciation to David B. Geslison for allowing him to copy this document.

[22] The Directory of the General Authorities and Officers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Presiding Bishopric, 1936), 91, evidences Byron commenced his mission under Roy A. Welker, president of the German-Austrian Mission. However, by the time his mission concluded in 1938, The Directory of the General Authorities and Officers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Presiding Bishopric, 1938), 92, indicates that President Albert C. Rees was overseeing the mission with whom Geslison would have sought permission to visit Iceland on his way home. Thanks is expressed to Melvin L. Bashore, Senior Librarian at the LDS Church Library in Salt Lake City for providing the author with this information. The Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), December 1935, 7, lists the name of President Walker. Apparently there was a mistake made in this typescript, and the name should have been Welker. The Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), June 19, 1938, 300, notes, “President Rees gave me my release.”

[23] “Autobiography of Byron T. Geslison,” 9.

[24] “Autobiography of Byron T. Geslison,” 9.

[25] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), July 10–11, 1938, 314–15, reveals that Byron was met by a relative referred to as “Sigrater Brynholfson’s brother.” Geslison soon other Icelandic relatives referred to as “Bjorg Sighvatsdottir [and] two young grandchildren.” After spending just one day on the Westmann Islands, he went to Reykjavík by ship.

[26] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), July 10–11, 1938, 316–17. Byron’s diary also reveals that he had several missionary experiences with his Icelandic relatives. For example, diary entries for the dates of August 11, and 20 (pages 332, 336) reveal that he taught a relative named “Ganja” the Joseph Smith story and other principles of the restored gospel. His relatives seemed to be particularly struck by the health code Byron strictly adhered to, which included abstaining from alcohol, smoking, tea, and coffee. See, for example, diary entries for July 14, 1938 (318) and August 21, 1938 (337). The August entry reveals the wonderful relationship Byron had developed with his relatives, although he would not bend in his commitment to living such a code: “I told them that I didn’t condemn them for it [smoking or drinking alcohol and coffee], I merely didn’t do it myself. I said I probably have other faults not of that nature, which are just as bad and could be worse.”

[27] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), July 10–11, 1938; July 18, 1928 [1938], 321–22.

[28] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), July 10–11, 1938; July 26, 1938, 325.

[29] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (1935–40), July 10–11, 1938; August 22, 1938, 339.

[30] Interview of Byron T. Geslison by Fred E. Woods, February 18; 2000, Spanish Fork Utah.

[31] “Autobiography of Byron T. Geslison,” 10.

[32] “A Brief History of the Icelandic Branch,” comp. Donald R. Knight, 13. The record for the date of May 28, 1967, further notes why the Norwegian Mission president accompanied Elder Hunter: “Branch transferred to Norwegian Mission.”

[33] Grant R. Ipsen, “Report: Trip to Iceland,” in Reykjavík Branch Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 1.

[34] Grant R. Ipsen, “Report: Trip to Iceland,” 1–5.

[35] “History of District,” Reykjavík Branch Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 3. This document is a compilation of salient features of the district taken from other Church records.

[36] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), November 19, 1974.

[37] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), November 19, 1974.

[38] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), December 30, 1974.

[39] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), January 6–7, 1975.

[40] Byron T. Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 4. A copy of this report was given to me by Byron before his passing on October 10, 2001. This typed manuscript is twenty-eight pages long. On the cover is a note probably written by Byron: “This report was presented to the First Presidency, the Quorum of the Twelve and the missionary committee. 4 copies were deposited in the Church Historian’s office.”

[41] Letter of Byron T. Geslison to his sons Daniel and David Geslison, dated January 8, 1975. The author thanks Dan for permitting him to have a copy of this letter.

[42] Interview of Daniel, David, and Melva Geslison by Fred E. Woods in Spanish Fork, Utah, May 22, 2005. Phone conversation with Daniel Geslison, May 23, 2005. Other members of the Geslison family, Elaine, Allen, and Kathy, were married and did not accompany their parents to Iceland.

[43] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), February 13, 1975.

[44] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 4.

[45] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), February 13, 1975.

[46] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), April 6, 1975. The following month Byron’s diary, dated June [May] 22, also reveals that LDS Icelanders in Spanish Fork continued to financially assist the Geslison family mission: “We received $200.00 from Myrtle [Johnson] and [her twin sons] Richard & Robert Johnson. We can’t get over their generosity.”

[47] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), April 6, 1975. Byron also notes that prior to their departure, a Salt Lake City travel agency staff dealing with their transportation desired to see them: “The people in Murdock Travel heard we were the ones going to Iceland, [they] wanted . . . to see what we looked like & what Icelander’s looked like.”

[48] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), April 1975. An entry from this diary dated March 10, 1975, reveals that Payne had previously been in contact with the Geslison family and suggests that high costs of housing probably dictated why the Geslison’s were temporarily staying with Payne. Byron wrote that on this date the Geslison’s received a letter “from Dr. David Payne, Melva read it over the phone. Price’s seem very high. Many good tips.” The Geslison family first lived in the apartment that Dr. David Payne had been renting, who was a visiting professor teaching sociology at the University of Iceland. According to a document titled “History of the District,” Icelandic District Records, Reykjavík Iceland, 3, at this time Dr. Payne, his wife, and their infant daughter were Latter-day Saints from Provo. This record also indicates that “there were five known Icelanders living in Reykjavik, who were members of the Church. The small group functioned as a dependent group of the Branch at Keflavik.” It appears that “dependent group,” stated herein actually means that a small group of Saints met independently but were still under the jurisdiction of the Keflavík Branch. After the Payne family departed, the Geslisons had to move as well. At the commencement of their stay, the twins slept on the floor with coats over them for warmth (interview of Daniel, David, and Melva Geslison by Fred E. Woods in Spanish Fork, Utah, May 22, 2005.

[49] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 4–5. In the May 22, 2005, interview with the Geslisons, the author further learned that Þorsteinn had first heard about the Church during World War II (1943–44). Some unknown person had approached him while he was apparently reading anti-Mormon literature and handed him a copy of the Book of Mormon with the brief comment that he would like it a lot better than what he was reading. Years later, Þorsteinn corresponded with Salt Lake City about the Latter-day Saint beliefs and as a result, the Church assigned Utah Icelanders John Y. Bearson and Kate B. Carter to stay in contact with him for the Church. In 1974 Þorsteinn was baptized by a military officer stationed at Keflavík named William Waites, from Moses Lake, Washington. One of the things the Geslisons noticed about his apartment was that he had purchased nearly every book the Church had ever published. The Reykjavík Dependent Branch Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 1976, 1, notes, “Upon their arrival to Iceland, the Geslisons found a small military branch of the Church on the NATO airbase in Keflavik. Part of the membership of the branch were 8 Icelanders. Thorsteinn Jonsson, a fisherman and only active Icelander, had a testimony of the Church for 15 years during which time he regularly bought and read Church books. He was finally contacted by the elders of the Branch, baptized and ordained an elder a year and a half before the Geslisons arrived. A Book of Mormon in English, given him by an American friend while at sea, led to gaining of a testimony long before he met Pres. William Waites and Clyde T. Swasey of the Keflavik Branch.” Þorsteinn Jónsson was born January 9, 1918, and died October 12, 1997. The notation of “8 Icelanders” in this document deserves special mention, inasmuch as the “8” is the only item written in bold. Dan Geslison suggested to the author that this number should actually be four. It appears that the “8” may have been added later.

[50] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), April 22, June [May] 22, 1975.

[51] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (June 8, 1975, to April 1977), June 27, 1975.

[52] According to the Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), May 6, 1975, Brother Payne left Iceland on May 6th. The Diary of Byron T. Geslison (June 8, 1975, to April 1977) discloses that during their first few months in Iceland the Geslison family faced the challenge of high costs in both lodging and furniture. See, for example, entries for the dates of July 24, 26; and August 5, 8, 1975. In fact, diary entries for September 11–12, 1975, reveal that they did not find an apartment to rent and adequate furniture until the day before two young elders (Gary Buckway and Blake Hansen) had been sent to help augment missionary work in Iceland. The furniture consisted of “six beds and 6 chairs, a sofa set with two chairs and two tables.” The six beds made it possible for Byron, Melva, the twins, and the new missionaries all to sleep under the same roof. This needed success just before the arrival of the missionaries seems to have been largely influenced by Byron’s tenacity and faith. Although the Geslison family had struggled to find adequate lodging for over two months, in a July 26, 1975, entry Byron writes optimistically, “I know he [God] will guide us to the right apartment . . . . We will not be overcome nor will we be discouraged because of what the Adversary can do because God’s power is so much greater. The stormy gloomy days merely cause me to try twice or 3 times as hard to be cheerful, positive & faithful & rely on the merits & mercies of Christ for I have no such merits nor powers myself outside His matchless power. I can only glory in Him.”

[53] Interview of Daniel, David, and Melva Geslison, May 22, 2005.

[54] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), May 1, 1975.

[55] “Autobiography of Byron T. Geslison,” 14. At the conclusion of the Geslison interview, May 23, 2005, the point was made that the LDS servicemen on the NATO base in Keflavík were a great strength to the Geslisons and provided them with whatever they needed, including transportation, food, and if needed, more men for the missionaries to go out proselytizing with. Finally, when they stepped onto the base, they felt as if they had a reprieve from the rugged Icelandic experience they were encountering, perhaps the next best thing to home.

[56] Interview of Daniel, David, and Melva Geslison, May 22, 2005.

[57] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), April 20, 1975.

[58] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (November 1974 to July 7, 1975), April 21 [22], 1975.

[59] Journal of Daniel Geslison, no date included.

[60] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 5.

[61] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 5.

[62] Diary of Byron T. Geslison (June 8, 1975, to April 1977), August 30, 1975.

[63] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 7. In the spring of 2004, the author visited Iceland to conduct research and to lecture at the University of Iceland on the topic of Icelandic Mormon immigration to Utah. During his visit to Reykjavík, he was also interviewed on Iceland’s prime-time television program Kastljósið, on radio, and also by Guðni Einarsson, a reporter from Iceland’s newspaper Morganblaðið. Each of the interviews provided opportunities to discuss the history of Icelandic Latter-day Saints at home and abroad as well as their religious beliefs which stimulated immigration to Utah in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

[64] Phone conversation with David Geslison, May 19, 2005.

[65] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 17. The Thordur Didricksson book Geslison is referring to is treated in Appendix B.

[66] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 17.

[67] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 4. The Diary of Byron T. Geslison (June 8, 1975, to April 1977), June 12, 1975, evidences that Pállson was paid $165.00 [kroner] for translating a tract called the Plan of Salvation. On this same date, Geslison also recorded that he and a small group had visited with the king of Sweden, “King Karl Gustav,” for about an hour and a half at the Swedish embassy. King Gustav was given a copy of the Book of Mormon during this visit.

[68] Interview of Daniel, David, and Melva Geslison, May 22, 2005.

[69] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 14. “Historical Events [of the] Reykjavik Dependent Branch, Reykjavík Branch Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 1977, 1, for the date of July 24, 1977, notes that “Sveinbjorg Gudmundsdottir was called to be an official translator for the Church. She will quit her job at samband to do this. This will be a full-time job for her.” Although Byron estimated that the translation would be done in about a year and a half, it was not completed until the end of 1979 and was not actually printed until 1981.

[70] Phone conversation with David Geslison, May 23, 2005.

[71] Journal of Daniel Geslison, May 2, 1976. Daniel also notes, June 6, 1976, that Sveinbjörg was baptized into the LDS Church. This was the first baptism in the mission in over a year.

[72] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 15. An entry from the Diary of Byron T. Geslison (June 8, 1975, to April 1977), August 25, 1975, notes, “We decided to go to the radio station & talked to the head man. He was very kind & polite & seemed very interested & wanted to talk to me about the radio discussion. He said he would listen to the Tabernacle Choir tapes & Spoken Word. . . . I told him that it was the most famous & longest continuous program on radio in America & that they could use it weekly as they would like.”

[73] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 15–16. Geslison, 23, also points out that filming of another sort was going on which influenced family history research for both Latter-day Saints as well as the people of Iceland in general. “The government allowed the Church to come in and microfilm many of their records and they have a set of these microfilms in their national library, which are made available to their people for use. The members have been anxious to begin their genealogies as soon as they have learned why the Church has placed so much emphasis on it and what their individual responsibilities are.” In his December 1977 report at the close of his first mission to Iceland, Geslison, 28, recommended the erection of an LDS Branch Genealogy Library in Iceland that he felt would increase the amount of family history research because the National Library of Iceland allowed usage of the genealogical films only during its operating hours between 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., which did not generally fit into the busy schedule of LDS Church members.

[74] “History of the District,” Icelandic District Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 3, notes, “On 8 August 1976 a Dependent Branch [known as the ‘Reykjavik Dependent Branch’] was organized to serve the members in Reykjavik. At this time there were ten Elder Missionaries and one Senior Couple serving in Iceland as Missionaries.” The Reykjavík Dependent Branch Records, Reykjavík, Iceland, 1, states that by July 1976, “The Kevlavik Branch had grown unbelievably to about 130 members since the arrival of President Geslison and the missionaries, not only with Icelandic converts but also with American Mormon families receiving military assignments to Iceland. The members of the Keflavik Branch have done everything possible to foster the beginning missionary labor. On July 25th, 1976, the first sacrament meeting in Icelandic was held in Kopavogur with President Geslison presiding and conducting.”

The Church News also published the glad tidings of the growth of the Church in Iceland. An article titled “Hostility Melts in Iceland” (August 20, 1977, 8–9) noted that “In . . . 1975 a branch of the Church was organized in Iceland on the American military installation at Keflavik. About 130 members, American servicemen and their families, were organized as part of the Denmark Copenhagen Mission. . . . Now an additional branch of the Church has been organized at Reykjavik.”

[75] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 12–13. Deanne Walker, “A Burning Testimony in Iceland, Ensign, October 1997, 61, notes that Maria Rosinkarsdottir was “the first Icelandic Relief Society president.”

[76] Interview of Daniel, David, and Melva Geslison, May 22, 2005. Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland December 1977,” 23, notes that the Icelandic branch in Reykjavík was strengthened through music: “Thru the help of several people in Spanish Fork a small organ was secured and sent to us. This was a great help in our work. There have been about fifty [LDS hymns] translated and a few old Icelandic hymns that can be used, so that now a small song folder is being prepared for the use of the Icelandic Branch until enough hymns can be translated to print a songbook.” The Diary of Byron Geslison (June 8, 1975, to April 1977), September 1, 1975, notes, “mailed letter to Frank O’Brien clearing the way for the organ.”

[77] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 20–21. In late 1977, Geslison further writes, 22, “The Church approved the construction of a chapel in the early spring of 1977. The status of this project is that the City of Reykjavik has tentatively approved the building site, but final approval is being awaited as it goes through the City Engineer, the building committee, zoning committee and other agencies. . . . The site appears to be a good one. It will be in the center of greater Reykjavik, readily accessible by bus and near roads which lead directly from the larger population centers near Reykjavik, such as Kopavogur and Hafnafjordur.” However, a chapel would not be dedicated in Iceland until the summer of 2000.

[78] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 21.

[79] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 18–19.

[80] Geslison, “Mission Report of Iceland: December, 1977,” 19–20.