Gathering Converts from the Land of Fire and Ice (1873–1914)

Fred Woods, “Gathering Converts from the Land of Fire and Ice (1873–1914),” in Fire on Ice: The Story of Icelandic Latter-day Saints at Home and Abroad, (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 75–103.

Although Þorsteinn Jónsson never returned to walk the streets of Reykjavík or visit any part of Iceland, twenty-two native Icelanders who had previously immigrated to Utah did return as LDS missionaries during the period of 1873–1914. [1] Of this group Magnús Bjarnason and Loftur Jónsson were the first to be called. [2] They had emigrated from Iceland in 1857 with a small company destined for Spanish Fork, as previously discussed. [3] Bjarnason and Jónsson launched the second and largest wave of LDS Icelandic immigration to Utah, which subsided at the turn of the twentieth century. This was also a time of mass emigration from Iceland as a whole; from 1872 to 1900, about sixteen thousand of the total population of seventy thousand emigrated, mostly to North America. After 1900 very few left. [4]

Proselytizing amid Stiff Opposition

Bjarnason and Jónsson arrived at the Westmann Islands on July 17, 1873, and commenced preaching the gospel. They met strong opposition by the Lutheran clergy. Magnús Bjarnason remembered, “We were called into court three times, but after being submitted to a rigid examination we were again set at liberty.” [5] By the time the missionaries left the Westmann Islands in the spring of 1874, a branch had again been organized, [6] and eleven Icelanders had caught the spirit of their message and gathered with them to Zion. The missionaries’ labors had been rewarded, notwithstanding the fact that they had experienced much persecution, and had been exposed to harsh weather. [7] Einar Eiríksson, one of the Westmann Islands converts of 1874, wrote of the spiritual preparation he received prior to the arrival of the missionaries, “having been appraised [apprised] of their coming by dreams and visions.” [8]

In 1875 two more native Icelanders, Þórður Diðriksson and Samúel Bjarnason, who had previously gathered to Utah, were called to labor in their homeland for one year. Although they did not baptize anyone during this time, they established many friendships, and several Icelanders immigrated with them to Utah when they concluded their mission. [9] Three years after his return to Spanish Fork, Diðriksson wrote the first known Icelandic missionary tract, consisting of 186 pages. A Voice of Warning and Truth was consistently utilized in the late nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth century. [10]

Until 1880 missionary work of the previous three decades had been largely confined to the Westmann Islands. In the spring of 1879, Elders Jón Eyvindson and Jacob B. Jónsson were called on a mission to labor in Canada before continuing on to Iceland. However, they labored only a few months in Winnipeg and New Iceland, where they held fifteen public meetings. [11] They then continued to Iceland, where they labored on the mainland, using Diðriksson’s missionary tract. [12]

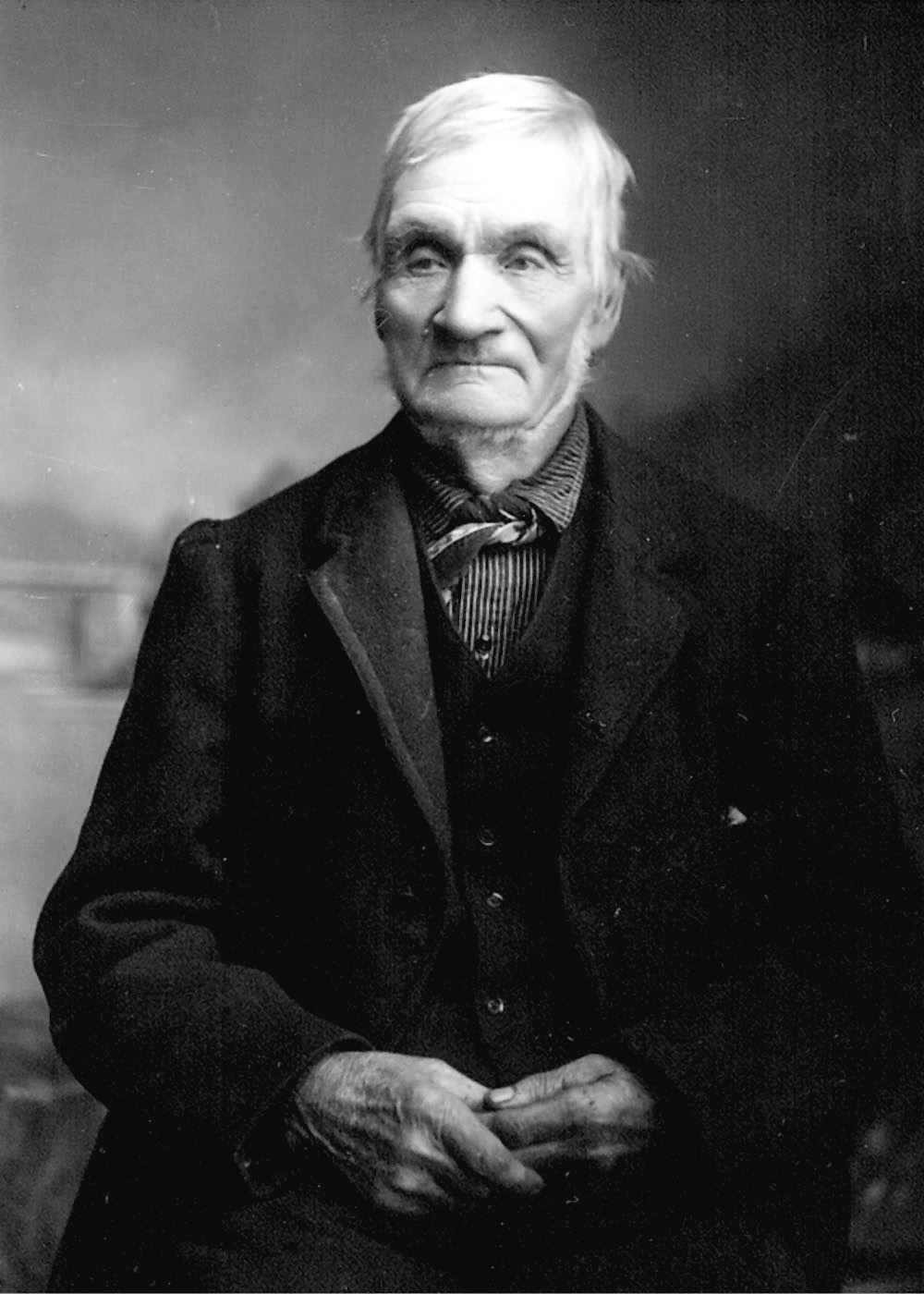

Magnús Bjarnasson (above) and his companion, Loftur Jónsson, were the first missionaries from Utah to be called to Iceland. They helped launch the second and largest wave of LDS immigration to America. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

Magnús Bjarnasson (above) and his companion, Loftur Jónsson, were the first missionaries from Utah to be called to Iceland. They helped launch the second and largest wave of LDS immigration to America. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

Upon arrival, Jón Eyvindsson wrote concerning the opposition he and his companion immediately faced: “It is the same here as we experienced in Canada. . . . The magistrate and priests make great opposition against us. They have forbidden the people to lend us their houses to preach in. . . . There is great intolerance here. . . . It is difficult for us to get at the people, to warn them.” [13]

Notwithstanding, soon thereafter Elder Eyvindsson baptized three people in Reykjavík, the first known baptisms in the capital city. [14] Eyvindsson wrote concerning this newsworthy event, “When the report spread about the baptism of these three sisters, the spirit of persecution was fiercely displayed by the people, and we were in danger from mobs. The lawyers accused us of rambling about in idleness [vagrancy], which is contrary to the law, because we travel about to preach the Gospel.” Further, “the magistrate of the town called us up twice for examination and finding us guilty of no crime, he banished us from the city and forbad us to preach. However we returned, and the chief of police put us in prison for two days. We were then taken before the magistrate again . . . [and ordered to] pay of fine of 100 Danish crowns each.” [15]

Jón Evyindsson was a missionary companion to Jakob B. Jónsson. They served for a short time in Canada before continuing to their mission in Iceland from 1879 to 1881. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

Jón Evyindsson was a missionary companion to Jakob B. Jónsson. They served for a short time in Canada before continuing to their mission in Iceland from 1879 to 1881. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

The Icelandic mission history also notes, “The baptizing of these three persons in Reykjavik set the whole town in an uproar and the brethren could scarcely walk the streets without being attacked and stoned by the mob. At last they were arrested by the police, accused of vagrancy and imprisoned for two days.” [16]

Voyages and Travel to America

Nevertheless, when their mission concluded, Eyvindsson, Jónsson, along with a group of twenty-two converts from Reykjavík, embarked for America on the ship Camoens. [17] One of their converts, Eiríkur á Brúnum [Eiríkur Ólafsson], wrote about his experience on this voyage:

On the evening of the 8th of July, 1881 I went on board the ship Camoens, a horse transport ship of Kokkels, after I, with some effort, a scuffle, and some tribulation of soul and body, was made to protect my grandson, of 14 months old, before 10 sturdy men of Reykjavík, who intended to attack my daughter and tear the child from her bosom at the command of her child’s father, who then wished to be such, but would not acknowledge the boy when newborn. [18]

On July 12 they landed at the dock of Granton’s Harbor near Edinburgh, Scotland. The group then traveled by train to Liverpool before embarking on the steamer Nevada. [19] Having crossed the Atlantic, Elder Jón Eyvindsson reported in a letter to British Mission president Albert Carrington of the successful voyage on the Nevada, over which Eyvindsson presided, noting that an Icelandic mother had given birth to twins:

We have had a pleasant journey, and for the most part good health and spirits. On the 23rd and 24th we had strong wind blowing from the south?west, and the rough sea began to make the sisters seasick. Peace and satisfaction have existed. We have had our prayers daily. We expect to reach New York tomorrow morning.

On the 25th, one of the sisters had twins. Her husband is with the company. Both the mother and the children are doing well. One is a boy and the other a girl. The name of the boy is Halldór Tómas Atlander, and was blessed by Elder J. [John] Eyvindson, that of the girl, Victoria Nevada, and she was blessed by Elder J. [Jacob] B. Johnson. New York, July 29th. We arrived at Castle Garden at 11 o’clock yesterday, all in good health and spirits, and we expect to leave here at 6 p.m. tomorrow night. [20]

By the time Eyvindsson returned to his home in Spanish Fork he could report to being an eye-witness to multiple births and also to the conversion of many souls. During his ministry, which lasted two years and four months, he and his companion had witnessed twenty-eight baptisms, and during this same period fifty-seven Icelanders had immigrated to Utah. [21] Evindsson and Jónsson had launched the peak decade of LDS emigration, the 1880s. [22] Yet missionary work in Iceland continued to be as hard as ice; conversions came only as a result of much travail. One missionary, writing in 1881 to the Scandinaviens Stjerne, noted, “Conditions in Iceland are deplorable.” This was largely the result of a famine in the land and the fact that the people were filled with “bigotry and hatred toward the Latter-day Saints.” [23] In this same year, a ray of sunlight shone on the Icelandic Saints when Spanish Fork Icelander Jón Jónsson translated the first book of Nephi into Icelandic. [24] Now, for the first time, Icelanders could read in their native tongue about Lehi and his family’s successful voyage to a promised land.

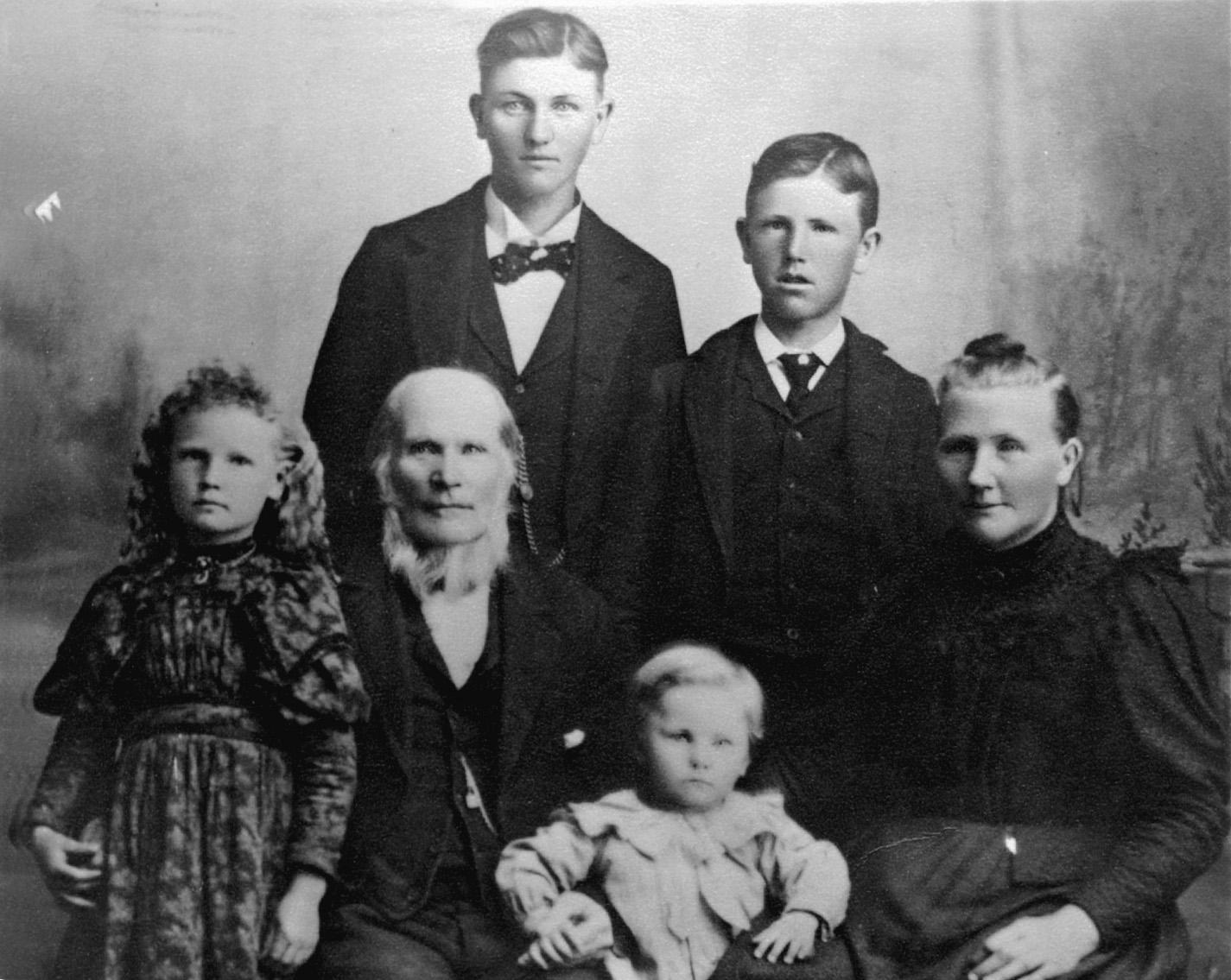

Jón Jónsson and his family. He was the first person to translate the book of 1 Nephi into Icelandic. Courtesy of Frances Hatch, great-granddaughter of Jón Jónsson.

Jón Jónsson and his family. He was the first person to translate the book of 1 Nephi into Icelandic. Courtesy of Frances Hatch, great-granddaughter of Jón Jónsson.

In 1883 John A. Sutton reported his experience of leading a group of LDS Icelandic emigrants across the Atlantic, having met them in Liverpool just prior to embarking:

We arrived here [Queenstown] at 9:35 this (Sunday) morning, all well, no seasickness. With the assistance of the interpreter, I effected an organization of the Icelanders, and appointed Elder Thorarinn Bjarnason to take charge, and have morning and evening prayer at 7 a.m. and 8 p.m. They appear to be very good people. I am studying Icelandic, with the assistance of a Danish and Icelandic Grammar. [25]

As noted, the year 1886 was the peak year for baptisms and emigration. [26] Their successful journey nevertheless did not come without a price. [27] One group who crossed the Atlantic in 1886 aboard the Alaska reported their challenge of passing through customs at New York:

Brother Hart [28] met us at the landing, and after being introduced to the Saints, rendered us valuable assistance in getting our luggage inspected etc. When we reached Castle Gardens we had considerable delay and trouble in answering needless and impertinent interrogatories by the Emigration Commissioners, who were seemingly determined to find fault. This was the more apparent from the fact that the most rigid scrutiny and closest investigation in the examination of the condition and prospects of the Icelandic Saints were observed in every detail, consuming more time with the twenty-three of our people than with 375 other emigrants who had previously passed muster. [29]

Even the New York Times picked up on the determent of the Icelandic Saints. In an article titled “Mormons with Little Money,” the editor noted the fact that “four families of Mormon immigrants from Iceland arrived yesterday in the Guion steamship Alaska. They numbered 25 persons all told. They were not as well clad as the average Mormons, and the whole party could not show more than $25 when they landed at Castle Garden.” [30]

Arrival of a Noble People

In spite of such obstacles, these Latter-day Saint Icelanders made their way to Utah, where they combined their efforts with those of other Icelandic emigrants in having a positive impact on the state. The Millennial Star depicted these emigrants thus: “All the Icelanders in Utah are living in Spanish Fork. They are an industrious, frugal people, and soon acquire comfortable homes, and are able to assist their less fortunate friends in emigrating from their far off native land.” [31]

As 1887 dawned, an article by Icelandic convert John Torgeirson outlined some of the salient features of his native land and noble people. Among other things, Torgeirson mentioned that the history of Iceland contained more evidence of Israelite origins than the history of any other country. [32] He also boasted of the fact that literacy in Iceland was unmatched: “Idiocy is nearly unknown, insanity is very rare and only two murders have been committed during the last one hundred years. . . . The National Library in Reykjavík is the largest, having over 10,000 volumes.” [33] Such a noble legacy of literate people no doubt influenced Utah for good.

Throughout 1887 the Icelandic Saints continued to gather. One small group (about twenty-two to twenty-five in number) embarked from Iceland on the Thyra and landed in Leith, Scotland, before taking a train to Liverpool, the primary port of embarkation for the Saints. From Liverpool they joined other foreign converts and crossed the Atlantic on the Wyoming. This group chartered a new route of emigration, which had just been altered for the 1887 season. Instead of traveling directly from New York to Utah, this company reembarked from New York and took a twenty-four hour trip on the Old Dominion Steam line, coming to port in Norfolk, Virginia. They then continued their travel via Kansas City and Denver by rail, arriving in Utah on July 25, 1887. [34]

A Poor Harvest on Difficult Terrain

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, missionary work in Iceland continued to be difficult. Conversions were sparse, and few Mormon Icelanders immigrated to Utah. During this period the elders continued seeking converts primarily on the southern coast of Iceland’s mainland, establishing their headquarters at Reykjavík, with occasional seasonal trips to the Westmann Islands. [35] However, others traveled to different regions of the country in search of more fertile fields. In the fall of 1894, Elder Þórarinn Bjarnason [36] wrote of challenges he faced traveling across Iceland’s wilderness to the eastern territory of Iceland.

I am traveling on foot, except when I have a guide to take me across the rivers and through unknown places. Once in crossing a large river on a ferry boat, we became fast in an icefloe which threatened to drive us into the sea. The breakers were very dangerous, and would certainly have upset the boat if we had been taken a little further out. We barely escaped by throwing a rope to those people who were standing on shore who caught it and kept us from going farther. [37]

Þórarinn Bjarnason was called to serve a mission to Iceland in 1894 and expressed the difficulties of traveling on foot across the land of fire and ice. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

Þórarinn Bjarnason was called to serve a mission to Iceland in 1894 and expressed the difficulties of traveling on foot across the land of fire and ice. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

Nearly a decade later, another LDS missionary wrote of such obstacles:

It is hardly safe to go a day’s journey without constantly having a guide. All traveling is done either on ponies or on foot, as there are no railroads, and only one short stage line in the whole country. To travel with the stage or “post wagon,” as they call it here would weary the patience of Job. I rode in it a short distance, but when I found that I could make time by walking I left it. [38]

A few months later, this same missionary described not only the difficulty of travel, but the season of the journey which augmented the problem:

During the winter season it is practically impossible to travel around in the country and, during the summer months the people are so busy that they could not, even if they felt so disposed, spare time enough to listen to an Elder explain the Gospel. Early in spring and late in autumn are the only seasons that farmers can be approached, for then they have a little leisure to spare. This being the case, the Elders have spent the winters in the towns and cities along the coast. These are the principal business places as well as seaports and rendevouz for sailors and fishermen. [39]

In 1899 Elder Halldór Jónsson, [40] struggling with poor health, reported his frustration of proselytizing during the summer months when the Icelanders were too busy working to stop and listen. “Nearly all the people are engaged for two months, from daylight to dark in haymaking.” [41]

This statement about the preoccupation of the Icelanders is indicative of the seasonal spiritual famine that occurred at the turn of the twentieth century, when few converts were made, and emigration subsequently ebbed. On April 29, 1901, Elder Lorenzo Anderson and Elder Jón Jóhannesson had literally washed their feet as a symbolic witness against all the inhabitants of Reykjavík. [42]

Determined Missionaries despite Hardships

During the fall of 1901, Elder Jón Jóhannesson traveled to the northwest and began proselytizing in the city of Akureyri. Finding there a more receptive people, he left a blessing rather than a curse on the inhabitants, although he initially met stiff opposition:

In October I took a steamboat to this town, which has about 1,400 inhabitants, and when I arrived here I was told it would be no use for me to stop here, as I would be killed. But I was not afraid, for I knew I was directed by the Lord and would be preserved by His power. . . . A Methodist preacher here commenced to warn the people against me and my tracts, but as a general rule the effect of that was to awaken the people to investigate. . . . I was led to invoke the blessing of the Almighty upon the country and its inhabitants, and since that time everything seems to have changed for the better. The whole community seems to be friendly towards me, and many have told me that they have been greatly deceived about our religion. The people as a rule are courteous, kind, intelligent and reasonable. They have lost confidence in their own ministers. They are seeking the streams of “living water.” [43]

Notwithstanding this friendly reception, apparently few actually drank from the water, and there is no evidence any of the inhabitants of Akureyri actually entered the waters of baptism. Certainly one reason for the Icelandic resistance to the gospel was expressed by Loftur Bjarnason, who explained:

Many lack courage to accept it because of the ridicule of their friends; others are so poor that they are forced to comply sometimes against their inner convictions, with the ordinances of the prevailing church in order that their children be not taken from them. It has often happened that baptized members of our faith, in order to retain their children, have been forced to allow the ministers to sprinkle and confirm them, otherwise the authorities would take these children from their parents and place them elsewhere. [44]

In 1903 Bjarnason reported his proselytizing labors among his relatives in the eastern part of Iceland, which was an area rarely visited by LDS missionaries. [45] He noted that his uncle, a Lutheran minister, had kindly received him. He added, “Once I had the pleasure of speaking publicly in a Lutheran church to a medium-sized congregation. The minister, a relative of mine, was liberal minded enough to allow me the privilege, the first of the kind that has been granted our Elders in this land.” [46]

Einar Eiríksson was the last missionary to serve in Iceland before the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

Einar Eiríksson was the last missionary to serve in Iceland before the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

During the first decade of the twentieth century few Icelanders converted to Mormonism; those who did immigrated to Canada. On June 16, 1903, Elder Jón Jóhannesson led a small company of LDS Icelandic immigrants to gather in Raymond, Alberta. [47] Gleaning these converts was well deserved as he had met stiff opposition and was even threatened with death during the time he labored alone for nearly three years as a missionary. [48] An example of the opposition he encountered occurred in the city of Reykjavík soon after his arrival. During a public meeting, a group of ruffians accosted him. He explains:

When I began to speaking they began to squeak and hollo, and then crying like a chicken, then to throw beans all over the people in the room like a hail-storm. When they found they could not hurt me with this, they began to shoot beans again until one of them hit me in the eye which hurt me very much, so I had to give up the meeting, though I spoke some time, and told them with great power and the spirit of prophecy what would follow their iniquities, and how they would bring down the judgments of God upon themselves. I further told them that I was not afraid of them, for even if they should kill me I was ready to seal my testimony with my blood, if they so desired, as others had done before. Then the lights went out, and as I went toward the door someone hit me on the head and broke my hat all to pieces, though I have worn it every day since, for the women-folk sewed it together for me. [49]

In spite of such tough opposition, the early-twentieth-century missionaries sent to labor in their native country of Iceland worked diligently, believing there were still souls to harvest in Iceland. Before his release, Elder Loftur Bjarnason, who labored faithfully and alone as a missionary from 1903 to 1906, reported thirty-eight members of the Church in Iceland. [50] In 1905 he described missionary labors in Iceland for the month of July: “We have visited the homes of sixty-five strangers; revisited fifteen of them; distributed six books and four hundred and sixty-four tracts; held four meetings and forty Gospel conversations.” Such strenuous efforts yielded but one convert; a woman who had been investigating the Church for over a year. [51] During this same year he noted, “Reykjavík is a city of about eight or nine thousand inhabitants, and it would be of great value for the work if the Church owned a house here.” [52] Regrettably, nearly a century passed before an LDS chapel came to Iceland.

In 1914, at the conclusion of Elder Einar Eiríksson’s second term as a missionary in Iceland, the Icelandic Mission was closed. [53] World War I loomed, and with it, emigration from Iceland in general ceased. It would be another six decades before the mission would reopen and an Icelandic branch be reestablished.

Notes

[1] The Historical Record of the Icelandic Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1873–1914, Church Archives, 2, contains a “Register of Elders” which lists the twenty-three missionaries by name. There are also individual columns for the date they arrived on their mission in Iceland, remarks concerning release and leadership appointment dates, and where they were residing at the time of their call. This document is not to be confused with the Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, which covers the years 1851–1914 and does not contain this register. It appears that it was most probably a compilation of Assistant Church Historian Andrew Jenson, who simply included the earlier years in this compilation along with this register. Fifteen of these missionaries resided in Spanish Fork, six in Cleveland, Utah, one (Jón Jóhannesson) in Raymond, Alberta, Canada, and one in Brigham City, Utah (Lorenzo Andersen), at the time of their call. Jóhannesson had lived previously in Spanish Fork but had migrated to Raymond in 1896. Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 12, lists Andersen as the lone Dane from the Danish Mission as all others were native Icelanders.

[2] According to La Nora Allred, The Icelanders of Utah (reprint, Spanish Fork, UT: Icelandic Association of Utah, 1998), 68, Magnús was born August 3, 1815, in Iceland, the son of Bjarni Jónsson. Further, “in 1853 he became a member of the LDS Church. He was married to Þuríður Magnúsdóttir, and in 1859 he and Þuríður emigrated to Spanish Fork, Utah. . . . He was a scholarly man who loved to read, and he is credited with founding the Icelandic library in Spanish Fork. He died in 1905 at the age 90 years, and is buried in the Spanish Fork Cemetery.”

[3] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 1857.

[4] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 17. Jonas Thor, Icelanders in North America: The First Settlers (Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 2002), 17, drawing upon data from Júníus Kristinsson, Vesturfraskrá, 1870–1914 (Reykjavik: Institute of History, University of Iceland, 1983), Table 7, writes: “Statistics show that in the beginning of the [Icelandic] emigration period, most of these Icelandic emigrants were young couples with children. During the first decade, from 1870–1880, 2857 individuals left Iceland for North America. Of these, 1894 were children, teenagers, and adults under the age of thirty. Four hundred and forty were between the ages of thirty and forty. This ratio did not change much throughout the entire emigration period of 1870 to 1914.”

[5] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 1873. Tom Checketts, “Here We Go Again: A Look at the History of Religious Rights in Iceland,” Fall 1999, unpublished paper in the author’s possession, 36, notes, “The conflict between the Mormons and the establishment came to a head when the Bishop of Iceland refused to recognize a 1873 marriage performed by a Mormon Elder and characterized the cohabitation of the couple as ‘illegal and immoral.’” Michael Fell, And Some Fell into Good Soil: A History of Christianity in Iceland (New York: Peter Lang, 1999), 230, adds, “Efforts to punish the couple, however, came to an end a year later, when Iceland’s new constitution guaranteeing freedom of religion came into effect.” Several articles on the subject of Mormons and civil marriage are attested in the Icelandic newspaper Ísafold. See, for example, these topic treated for the following dates: December 17, 1875; January 8, 1876; May 10, 1876.

[6] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, May 27, 1874, notes, “A branch of the Church was organized on Westmann Island with eight members. Einar Erikson (one of the converts) was ordained an elder by Loptur Johnson and appointed to preside over the branch.” In Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 7, Einar Eiríksson wrote, “After the departure of the Elders the branch was in a weak condition, as they had none of the church works excepting the bible. However, we held meetings every Sunday in my little dwelling house, the saints were united and the power of God was made manifest by healings and we had dreams and visions to strengthen our faith.” (Eiríksson wrote “Short History of the Iceland Mission” in 1912. This work is compiled at the end of the Icelandic missionary history.)

[7] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, May 29, 1874, lists the names of those emigrants and notes that only one of the eleven left as a member of the LDS Church. However, the other ten were baptized after arriving in Utah. The group sailed from Iceland to Great Britain on the ship Hermine and on the Nevada from Liverpool to New York.

[8] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, May 29, 1874.

[9] One of the emigrants had previously been baptized into the LDS Church, while the other three or four other emigrants had not yet been baptized (see Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 1875, August 8, 1875).

[10] Referring to Diðriksson’s tract, Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, Eiríksson notes, “I consider this book the best that has been published in the Iceland language on our religion.” A copy of this work is housed in the Church Archives in Salt Lake City. Byron Geslison, who was called to reopen the Icelandic Mission in 1975, indicated that the missionaries still used Þórður’s tract a century after it was written (oral interviews with Byron Geslison and his family in the winter of 2000).

[11] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 7–8. Concerning the brief mission of Elders Jónson and Eyvindsson to Canada, “The Gospel to the Icelanders,” Millennial Star, September 15, 1879, 587, notes, “They have, in accordance with a portion of their appointment, labored about three and a half months in Manitoba, in the Northern portion of British America, where about 2,000 Icelanders are located. During their ministry in that part they held seventeen meetings, three of which were in the open-air, the others in private houses. They encountered malignant opposition, incited, for the most part, by John Bjarnason, a Lutheran priest. . . . The priest circulated many false reports concerning the elders and counseled the people not to listen to and to shut their house against them. The meetings were, however, attended by from sixty to one hundred persons, and they left some believing in the Gospel and intending to gather to Utah this autumn.”

[12] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 1879. “The Gospel to the Icelanders,” Millennial Star, September 15, 1879, 587, notes that these missionaries had a copy of the manuscript and were planning on printing no less than two thousand copies of the tract. In a article written a quarter century later by President Loftur Bjarnason titled “The Work of the Lord in Iceland,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 145–47, he states, “The precious truths of this book contains (referring to Thordur Didricksson’s missionary tract) have been the cause of many accepting the Gospel and emigrating to Utah, where they are to-day staunch and faithful Latter-day Saints.” See Appendix B for this manuscript in its entirety.

[13] Letter of Jón Eyvindsson to President Wm. Budge, written from Reykjavík, March 18, 1880, “Missionaries in Iceland,” Millennial Star, April 5, 1880, 221. Jón Þorgeirson, “Iceland Items,” Deseret News, December 29, 1880, 767, notes that Eyvindsson and Jónsson, “had suffered imprisonment and all kinds of persecution. . . . The cause of this great persecution is that the Lutheran faith is universal in Iceland, and the Lutheran clergy have unlimited power there as there is no other sect in the whole country.”

[14] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, March 22, 1880, notes, “The names of these converts were Setselja Sigvaldsdottir (born in 1858), Sigridur Bjarnsdottir (born in 1834 in Reykjavik) and Sigridur Jonsdottir (born in 1846).”

[15] Letter of Jón Eyvindsson to President William Budge, Millennial Star, May 31, 1880, 350. See also Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, March 22, 1880. The story of the missionaries being arrested for vagrancy was also mentioned in a local Reykjavik newspaper, Ísafold, April 9, 1880, 36.

[16] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, March 22, 1880. As noted, at this time Þorsteinn Jónsson and Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur were both police officers in Reykjavik. They were also both witnesses at the trial of these two Mormon missionaries, and Sigríður Jónsdóttir (as noted in note 12), was one of the three women Eyvindsson baptized. She was also the wife of Þorsteinn. Þorsteinn joined the Church and gathered with his wife to Utah the following year. In the 1882 Reykjavik Parish Census, Þorsteinn’s age is forty-six and his status is “police officer.” The age of Sigríður is given as thirty-nine. Appreciation is extended to Jóhanna, an employee at the Reykjavík City Archives, for bringing this information to the attention of the author. After Þorsteinn immigrated to Spanish Fork and then moved to Cleveland, Utah, he communicated with his friend Borgfirðingur for many years. However, Borgfirðingur remained at home in Iceland as a Lutheran and never immigrated to Utah.

[17] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, July 7, 1881, lists seventeen of twenty-two emigrants by name.

[18] Vilhjálmur Gíslason, Eiríkur á Brúnum (Reykjavík: Ísafoldarprentsmiðja H.F., 1946), 116, trans. Darron S. Allred. Eiríkur á Brúnum is actually Eiríkur Ólafsson. According to Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 110, he was born by Eyjafjöll, in Iceland, November 14, 1824. Further, “he was married to Runveldur Runolfsdottir. He was a rancher and also operated a restaurant in Reykjavik. He was a writer and published a book which is still read in Iceland today. In 1881 he was baptized into the LDS Church, and shortly after he and his wife, their daughter, Ingveldur, and her son Thorbjorn Thorvaldson, emigrated to Spanish Fork, Utah. They traveled by train from New York, but at North Platte, Nebraska, Runveldur died of heat exhaustion. . . . In 1883 Eirikur returned to Iceland on a mission for the LDS Church. After his return, he moved to Independence, Missouri, about 1890. In 1891 he went back to Iceland where he married himself to Gudfina Saemundsdottir. He died in Iceland.”

[19] Vilhjálmur Gíslason, Eiríkur á Brúnum, 116. See John Bartholomew, Gazetteer of the British Isles: Including Summary of 1951 Census (Edinburgh: John Bartholomew & Son, n.d.), 301, for details regarding the location of Granton Harbor. The voyage from Iceland to Scotland and then down to Liverpool by train or by ship was the general pattern for the Icelandic LDS immigrants during the latter half of the nineteenth century. From Liverpool they then crossed the Atlantic to America. The United States port of entry most used by the Icelandic Saints was Castle Garden, which was located on the shore of New York City. It had an immigration depot from 1855 to 1889, which was replaced by Ellis Island in 1892. Only the first three LDS Icelandic immigrants to Utah came by way of the port of New Orleans. Commencing in 1855, Brigham Young sent all others to either Boston, Philadelphia, or New York, thinking it was too risky to bring the Mormon immigrants up the Mississippi River (via New Orleans) due to the threat of yellow fever and cholera (see Brigham Young to Franklin D. Richards, August 2, 1854, “Foreign Correspondence, Millennial Star, October 1854, 684, cited in Fred E. Woods, Gathering to Nauvoo [American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2002], 89).

[20] Jón Eyvindsson to Pres. A. Carrington, Millennial Star, August 29, 1881, 554–55. Such reports written by Church leaders on LDS company-chartered voyages were a general routine. Voyage accounts would be sent back to Liverpool, the mission headquarters for the LDS Church in Europe. Hundreds of these accounts are readily available in issues of the Millennial Star for the latter half of the nineteenth century. These and other first person LDS immigrant accounts are also available on a CD titled “Mormon Immigration Index,” which covers the years 1840–90 and is available for purchase through The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints distribution centers. The editor and compiler of this index is also the author of this work.

[21] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, July 7, 1881.

[22] As noted, research compiled by Bliss Anderson (a member of the Icelandic Association of Utah), reveals that 268 of 410 Icelanders who emigrated from Iceland to Utah during the period 1854–1914 did so during the decade of the 1880s. See Appendix A for a list of the names of these emigrants, which includes genealogical data, including birth date, place, and year of emigration.

[23] Marius A. Christensen, “History of the Danish Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1850–1964,” [Author: university?] (master’s thesis, 1966), 128.

[24] This is the first known translation of a portion of the Book of Mormon. The original is in the possession of Marian P. Robbins, the great-granddaughter of Jón Jónsson.

[25] Letter of John A. Sutton, Millennial Star, July 23, 1883, 479. Sutton may have been motivated to learn Icelandic due to his loneliness on the voyage. In a letter written two weeks later he commented that he would have rather taken a thousand Englishmen across the ocean because he found it difficult to converse with the Icelanders and did not have any Saint to converse with in his language (see Millennial Star, August 13, 1883, 527).

[26] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, December 31, 1886. Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 20, notes that sixty-three Icelanders emigrated to Spanish Fork in 1886. Bliss Anderson’s research suggests that as many as eighty gathered to Utah for this year.

[27] Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, Einar Eiríksson, “Short History of the Iceland Mission,” 9, indicated that in the spring of 1886 he traveled from the Westmann Islands to Reykjavík “to act as private agent for 15 emigrants who were going to Utah. I was instrumental in reducing their fares to Scotland from 70 crowns to 35, by correspondence from the Steamship Company.” Emigrants then generally took a train down to Liverpool where they joined with other European Saints who then crossed the Atlantic to America. In Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, 10, Eiríksson later summarizes his mission: “Having labored 14 months and 6 days . . . I baptized 25, and converted and assisted 57 emigrants to Zion, the majority of which were members of the Church, and most of the others were baptized after arriving in Spanish Fork.”

[28] This was James H. Hart, who served admirably as the emigration agent at New York from 1882 to 1887. He was a very successful politician and attorney and even continued to serve in the Bear Lake Stake presidency in spite of his seasonal emigration assignments in the East. See Edward L. Hart, Mormon in Motion: The Life and Journals of James H. Hart 1825–1906 in England, France and America (Salt Lake City: Windsor Books, 1978), for details of his life and experience as an emigration agent.

[29] “The Icelanders,” Millennial Star, August 9, 1886, 507.

[30] “Mormons with Little Money,” New York Times, July 19, 1886, 8.

[31] “From Iceland,” Millennial Star, November 5, 1883, 711.

[32] In a conversation with Byron Geslison (February 2000), Byron, who served as a patriarch in Iceland in the late twentieth century, indicated that every blessing he gave in Iceland reflected that the recipient was from the tribe of Ephraim. The only exception was a foreigner who was temporarily stationed at the NATO base in Keflavík.

[33] John Torgeirson, “The People of Iceland,” Deseret Evening News, January 24, 1887, 2.

[34] Between five thousand and six thousand Saints came through Norfolk on this new route between 1887 and 1890. For more information concerning the cause of the rerouting and the experience of these Saints through the port of Norfolk, see Fred E. Woods, “Norfolk and Mormon Folk: Latter-day Saint Immigration through Old Dominion, 1887–1890,” Mormon Historical Studies, 1, no.1 (Spring 2000): 73–91.

[35] Loftur Bjarnason, “The Work of the Lord in Iceland,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 146, further notes, “There are many parts of this country that have not been yet covered, as the Elders, who come here have labored principally in those localities in which they were born and reared. It is only along the southern coast of the mainland and in the Westmann Islands that the Gospel has to any extent been preached, while the greater portions of the northern and eastern countries have never been visited.” See also Millennial Star, March 24, 1904, 188, and May 12, 1904, 301–2, for evidence of seasonal proselytizing in the Westmann Islands.

[36] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 69, indicates that Þórarinn was born June 17, 1849, and was from Skafafell’s County, Iceland. In 1882 he and his wife, Byrnhildur Jónsdottir Bjarnasson, were converted to Mormonism and emigrated to Utah the following year with three of their children. Þórarinn died February 21, 1924. He is buried in the Spanish Fork Cemetery.

[37] Millennial Star, December 17, 1894, 806. Elder Bjarnason, writing a decade later, also spoke of the difficulties missionaries encountered proselytizing in the country. Here he noted, “Houses are scattered, being from a half mile to a mile and a half apart, and the only method of traveling is either by foot or on ponies. Often it is impossible to go from one farmhouse to another without being accompanied by a guide, on account of the dangerous streams that are to be encountered, which only experienced men can find the way to cross. To purchase a horse and pay a guide wages, together with other expenses, has made traveling in this country both expensive and difficult,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 146.

[38] Loftur Bjarnasson to Francis M. Lyman, September 20, 1903, Millennial Star, October 8, 1903, 645–46.

[39] Letter of Loftur Bjarnasson, “The Work of the Lord in Iceland,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 145–46.

[40] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 97, notes that Halldór Hansson was born in Skurðbær, Meðaland, Iceland, on March 1, 1956. In 1880 Halldór and his wife, Guðrún Jónsdóttir Einarsson, joined the LDS Church, and the following year they immigrated to Spanish Fork, Utah, with their son Johann. Halldór and his family lived in Spanish Fork as well as Cleveland, Utah; he died January 11, 1936 and is buried in the Cleveland Cemetery.

[41] British Mission Manuscript History, LDS Church Archives, November 2, 1899, 1. Andrew Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:342, notes that Halldór Jónson labored as a missionary in Iceland from 1898 to 1900. Five years later, Icelandic Mission president Loftur Bjarnason elaborated on the difficult climatic conditions in Iceland.

[42] “Record of Members of the Icelandic Mission, 1873–1914,” Church Archives, 40. Anderson, a Dane coming from the Danish Mission, was the only non-Icelandic missionary to serve in Iceland during this period.

[43] “Preaching in Iceland,” Millennial Star, July 3, 1902, 427–28.

[44] President Loftur Bjarnason, “The Work of the Lord in Iceland,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 147. Several months later, Bjarnason, “Notes from the Mission Field,” Millennial Star, September 1, 1904, 555, explained another factor which made proselytizing difficult, “There are many wicked stories afloat in this country about the ‘Mormons,’ and much time is spent in explaining to the people the absurdity and falsity of these tales.” One of the doctrines that received the most opposition in Iceland and in other parts of the world was polygamy, which was a practice that was rescinded through an official manifesto issued by the Church in 1890.

[45] Most of the missionaries concentrated on proselytizing on the Westmann Islands, the Reykjavík region and the western coast of Iceland due to the difficulty of traveling across the country, especially in winter. Therefore they consigned themselves principally to the western seaports where sailors, fishermen and people generally would gather during the winters (see Letter of Loftur Bjarnasson, “The Work of the Lord in Iceland,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 146. In this same year, Bjarnason wrote, “During our stay in Vestmanneyjar we had so won the hearts of the people that many expressed their regrets at seeing us depart. Although we did not make any converts there, we did make a host of friends, and several are earnestly investigating the Gospel” (Millennial Star, December 22, 1904, 812). The Westmann Islands was not only the place where the missionaries generally received their most welcome reception, but during the later half of the nineteenth century, it was where they plucked most of their converts, commencing with the arrival of the first LDS missionaries to Iceland in 1851. In another letter, Bjarnason reported in “Travelers in Iceland,” Millennial Star, May 12, 1904, 302, “Vestmanneyjar is a beautiful group of islands about twelve miles off the mainland in a southerly direction. The largest island of the group has a population of eight hundred souls, while the smaller islands are used principally for the pasturing of the sheep. . . . About two-thirds of those who have embraced the Gospel from this country have come from this place, and indeed we feel the same spirit of goodwill toward our people that has ever existed here. We have been better received than we could have anticipated, and we are beginning to think that the hospitality of the people is limitless.”

[46] Loftur Bjarnasson to Francis M. Lyman, September 20, 1903, “Word from Iceland,” Millennial Star, October 8, 1903, 645.

[47] “Record of Members of the Icelandic Mission, 1874–1914,” Church Archives, 78 ff. Page 88 indicates that the Saints who emigrated with Elder Jón Jóhanneson “took passage on the S. S. Laura for Raymond Alberta Canada via [the] Albion Line.” According to the Millennial Star, July 2, 1903, 426, Elder Jóhanneson and four Saints were to emigrate via Glasgow. The “Historical Record of the Icelandic Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1873–1914,” Church Archives, 14–15, 17, notes that three of the group were Guðfinna Sæmundsdóttir, Jón Grímsson and Guðnurður Jónsson. Elder Halldór Jónsson reported that due to the unfavorable temporal prospects in Iceland during this period, “many are emigrating to Canada, and many more would do so if their finances would allow” (see Millennial Star, July 5, 1900, 426). Further, the Raymond, Alberta, Membership Record (1901–12), Church Archives, lists the names of at least ten additional Icelanders living in Raymond during this period. It also records that some of these Icelanders migrated later to the Taber Ward, located a few miles away in the predominately Mormon area of southern Alberta, Canada. The Taber, Alberta, Membership Record, Church Archives, also lists the names of twenty Icelandic names in this ward.

[48] “Returning from Iceland,” Millennial Star, July 2, 1903, 426. Manuscript History of the Icelandic Mission, Einar Eiríksson, “Short History of Iceland Mission,” 11, notes that Jóhannesson arrived in Reykjavík on September 28, 1900. “When he arrived there he gave the statistical report of the saints in Iceland as follows: One Elder, one Deacon, 16 lay members, and 12 children not baptized belonging to the Latter-day Saints. During the missionary labors, he baptized ten, ordained three, and blessed thirteen also aided five to emigrate to America. So at the close of his mission there were: Three Elders, One deacon, 18 members and 17 children, making a total of 39 souls. While in Iceland Elder Johannesen composed and published a number of tracts which assisted in the promulgating the everlasting gospel. He received an honorable release in June, 1903, arrived in Raymond, Canada, July 20th and at Salt Lake City, December 5th.”

[49] “Abstract of Correspondence,” Millennial Star, December 20, 1900, 811. In an article titled “Returning from Iceland,” Millennial Star, July 2, 1903, 426, Elder Jóhannesson’s tenacity was noted, in spite of such hardships. In addition to the persecution it was noted, “Elder Johannesson has found himself without money at times, and has had to rely on the aid of the Lord. On one occasion he had to sell his walking stick and English Book of Mormon to supply his necessities. He has during his mission written a book and published over two thousand copies, besides publishing nearly eight thousand large tracts. . . . We wonder if there is any church in the world whose members would go under such trials and do such work, at the same time bearing their own expenses.” Further, in an article written by Loftur Bjarnason titled “The Work of the Lord in Iceland,” Millennial Star, March 10, 1904, 147, Bjarnson notes that the book Jóhannesson wrote was titled A Call to the Kingdom of God, which contained 224 pages. The author has a copy of this book in his possession.

[50] Loftur Bjarnason, “From Iceland,” Millennial Star, February 22, 1906, 121. Further, seven months later, the Millennial Star, September 20, 1906, 607, reported Loftur Bjarnason was in charge of fifty-three emigrating Saints from Iceland. An article titled “Items for Iceland,” in the Millennial Star, July 5, 1906, 427, mentioned that inasmuch as there were “ten Sisters in Reykjavik, he [Barnason] has organized a relief society in that branch. The Saints are paying their tithing and attending to their duties generally.” The Relief Society is an ecclesiastical organization for women in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was established in 1842 and has as its motto “Charity Never Faileth.” The Historical Record of the Icelandic Mission, 1873–1914, 62–63, reports twenty-seven LDS members and thirteen children under the age of eight. On these pages is a statistical membership list for the years 1900 to 1911. By 1911, only twenty-six LDS members and three children under the age of eight were recorded. The Autobiography and Journals of Andrew Jenson, August 14–21, 1911, Church Archives, reveals that Jenson, Assistant Church Historian, visited Reykjavík where he rented a hall in order to lecture on Mormonism. He and the local missionaries were disappointed with the outcome inasmuch as the hall held up to four hundred people, but only thirty-five attended. Furthermore, some left before the lecture was over. On August 19, 1911, Jenson writes, “It is, however, possible that some of them could not understand Danish.” Yet on the following day Jenson notes that he gave a second lecture in a different location where 75 people attended. Finally, he adds, “The records show that there are 26 members of the Church in Iceland.” According to an article titled “Will Write History of Iceland Mission,” Deseret News, March 2, 1926, cited in the Journal History of this same date, fifteen years later Jenson is mentioned as the person who would compile the “Manuscript History of the Iceland Mission,” the last of a series of worldwide mission histories to be written.

[51] “Report from Iceland,” Millennial Star, August 31, 1905, 554–55. “Traveling in Iceland,” Millennial Star, May 12, 1904, 301, Bjarnason describes even more taxing efforts to win souls: “During the months of March and April we have visited the homes of 250 strangers, distributed 676 tracts, held five private meetings with Saints and investigators, and baptized one person.”

[52] Elder Bjarnason, “Notes from Iceland,” Millennial Star, October 12, 1905, 653. Writing from Reykjavík, Halldór Jónsson noted five years earlier, “If we had a meeting house here we could get many listeners, and, I believe, many would join the Church” (“Abstract of Correspondence,” Millennial Star, April 12, 1900, 234).

[53] “Historical Record of Icelandic Mission 1873–1914,” 41, states, “July 8, 1914 Elder Einar Eriksen, who commenced his labors on the Island July 11, 1913, was released today, on account of a discontinuance of missionary work in Iceland, and in compliance with instructions received from the First Presidency.”