Epilogue

Joining Hands across the Waters

Fred Woods, “Joining Hands across the Waters,” in Fire on Ice: The Story of Icelandic Latter-day Saints at Home and Abroad, (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 185–221.

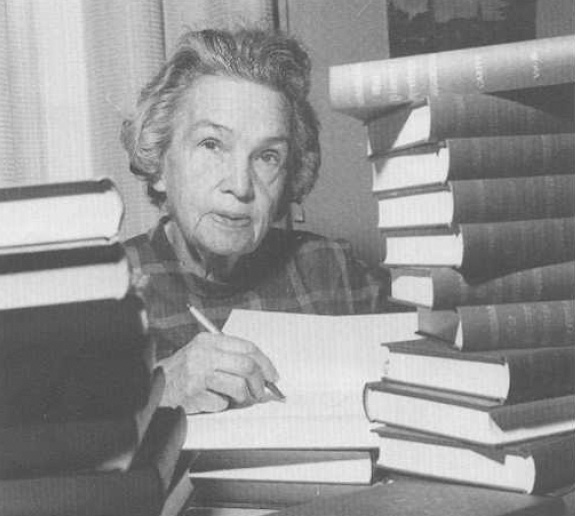

The Icelanders of Utah have remembered their roots in several ways. Visual reminders of loved ones as well as images of the fatherland decorated their homes. A continual exchange of letters has crossed the ocean to remind both countries of their common ancestry. No doubt the Westmann Islands and Reykjavík were mentioned in the streets of Spanish Fork, while native Icelanders spoke of friends and loved ones who had immigrated to Utah. Steady efforts were made by the transplanted Icelanders to maintain their native customs and traditions. Kate Bjarnson Carter wrote, “The Iceland people in Utah are said to have preserved folklore and customs of their mother country more than any other nationality who pioneered Utah.” [1]

Kate Bjarnson Carter was a prominent leader of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers in Utah and one of three Utah Icelanders to receive Iceland’s highest award, the Order of the Falcon. Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

Kate Bjarnson Carter was a prominent leader of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers in Utah and one of three Utah Icelanders to receive Iceland’s highest award, the Order of the Falcon. Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

“Iceland Days”

“Iceland Days” were established to retain the rich heritage of the Latter-day Saint Icelanders in Utah. [2] This annual festivity commenced in 1897 and was organized under the capable leadership and direction of Einar H. Johnson, who formed a committee to make plans for commemorating Iceland’s settlement in 874. [3]

In describing the first “Iceland Days” celebration held August 3, 1897, La Nora Allred wrote, “Poles and willows along the river in the bottoms were gathered, and a bowery was built on the north side of the amusement hall. The entire program was in Icelandic: Speeches were given. . . . Vocal solos were sung. . . . The Icelandic choir also sang several numbers. . . . There was also a grand ball in the evening.” [4]

JoAnna Woods, an honorary Icelander, demonstrates the craft of spinning wool as part of the activities of “Iceland Days.” Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

JoAnna Woods, an honorary Icelander, demonstrates the craft of spinning wool as part of the activities of “Iceland Days.” Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

Byron T. Geslison points out that elements of this general commemorative plan continued to be practiced early each August during the twentieth century, though the location for the event sometimes changed:

In the beginning they prepared boweries in which to hold the observance. They also had winter programs and committee meetings to prepare for the main summer event. Icelandic Day has been held in many different locations over the years. Some of the early ones were held in the diversion dam up Spanish Fork Canyon. Many of the participants fondly remembered the “dam parties,” as they were called then. Another favorite site was Castella Resort also up Spanish Fork Canyon. They would ride up in hay wagons, live in tents, swim in the outdoor and indoor swimming pools, and play baseball and other sports. Subsequently, Icelandic Day has been held in other Utah Valley locations including Geneva Resort, Park Roshe, Arrowhead and Canyonview Park, and most recently, the Spanish Fork City Park. [5]

Joseph Walker describes the celebrations: “For generations, descendants of those early immigrants have gathered in Spanish Fork on the first Saturday in August. The date coincides with an annual holiday in Vestmannaeyjar [Westmann Islands], an island just off the south coast of Iceland that was a haven to Icelandic Mormons.” One Icelander adds, “For years, our ancestors clung to each other. . . . They were family. In that sense, our gathering is a family reunion. It’s a way of maintaining ethnic identity and cementing ties to our Icelandic heritage.” [6]

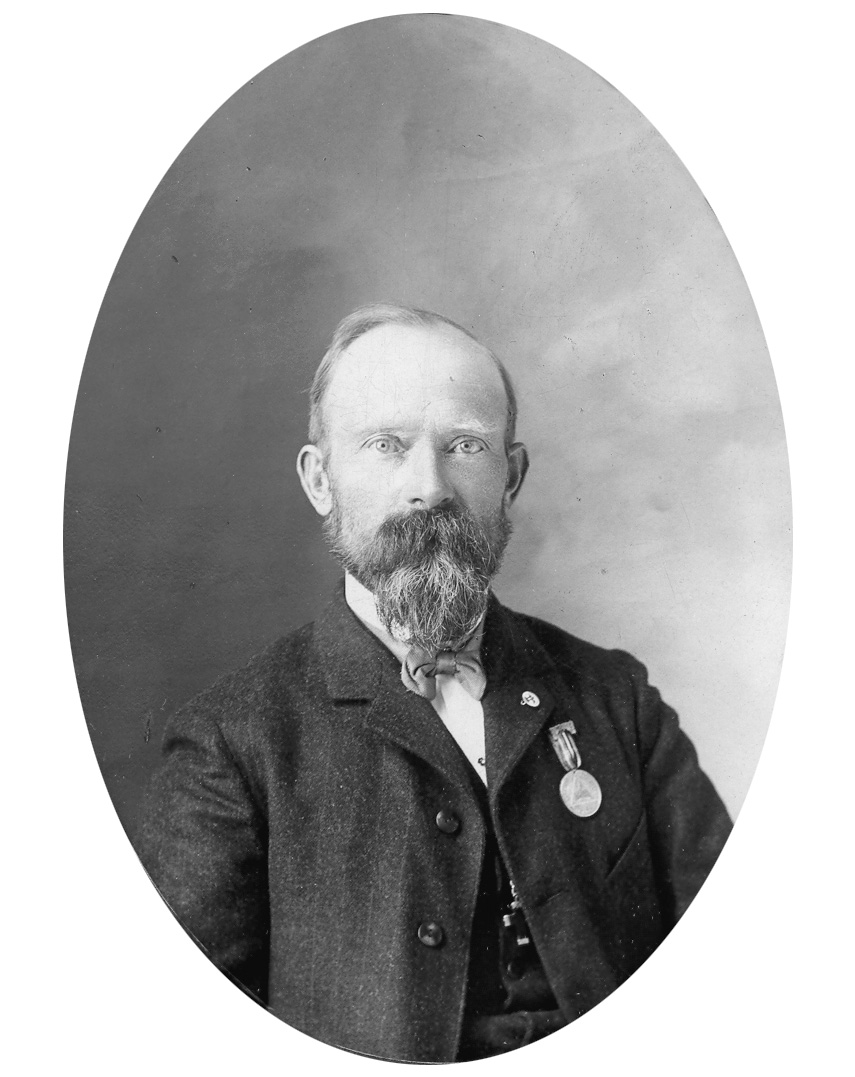

Such events helped to keep the Utah Icelanders united, although all did not embrace the predominant LDS faith within the borders of the state. Evidence for such unity appears in reports by members of the Icelandic Association as well as from newspaper articles that both Latter-day Saints and non-Mormons participated in the “Iceland Days” programs. For example, in 1900 the Latter-day Saint owned newspaper the Deseret Evening News reported the involvement of the Lutheran clergy. “In the afternoon an instructive speech on the Icelanders in Vinland, by Rev. R. Runolfson, was the first number on the program. . . . Rev. A. Gunberg read a historical and geographical sketch of Iceland, which was replete with data, and graphical descriptions of that island.” [7]

Reverend Runolfur Runolfson, a Lutheran clergyman, participated in the program of “Iceland Days” in 1900. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

Reverend Runolfur Runolfson, a Lutheran clergyman, participated in the program of “Iceland Days” in 1900. Courtesy of the Geslison family.

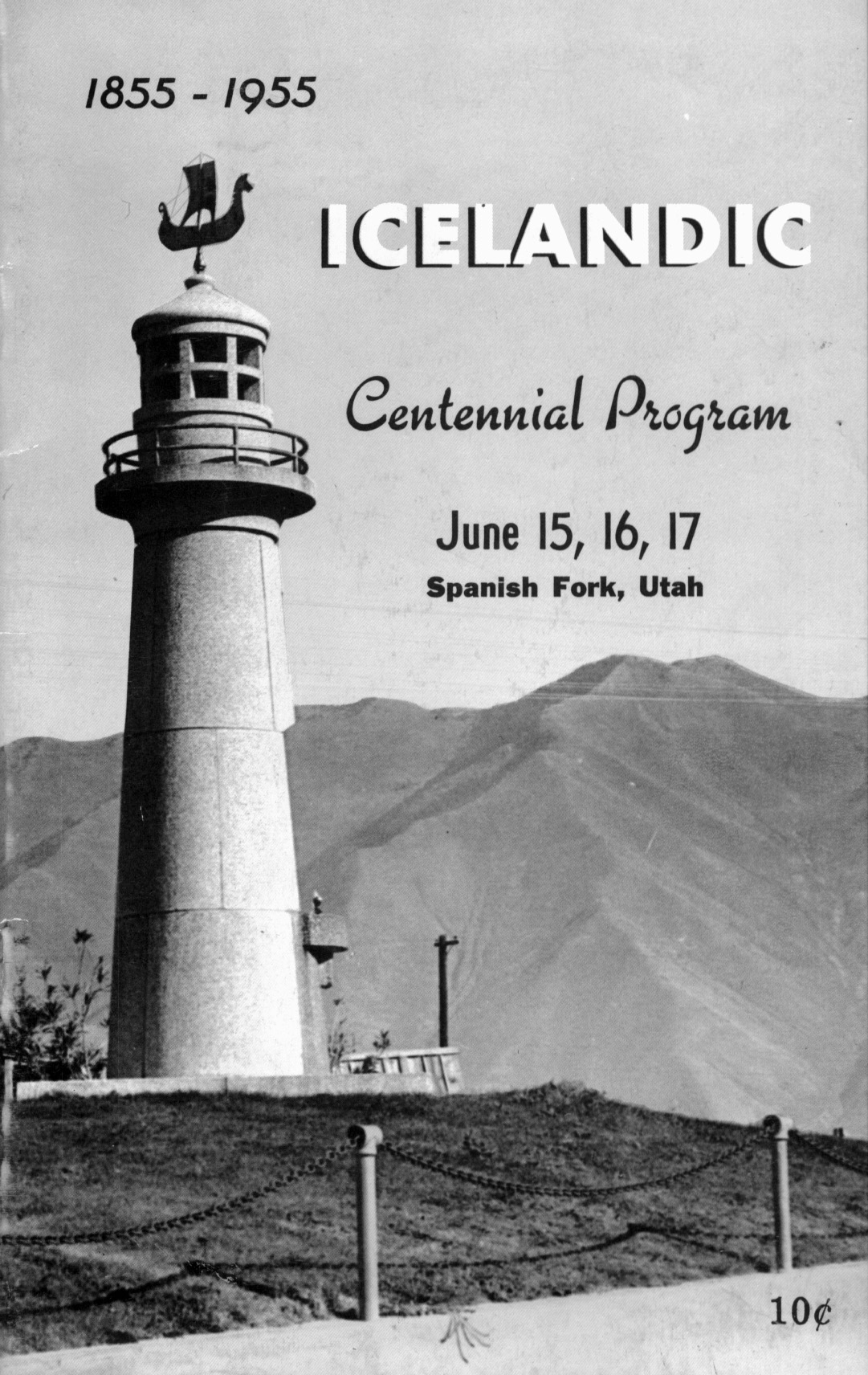

Icelandic Monument

One catalytic effort that established a permanent image for the early Icelanders was initiated during the “Iceland Days” commemoration of 1938. As August dawned, a beautiful monument was unveiled to pay tribute to the first sixteen Icelanders who immigrated to Utah. It was a replica of a lighthouse with a Viking ship model sitting on top and a plaque engraved with the sixteen names. The symbol reflects the seafaring background of the Icelanders and was erected by the Icelandic Association of Utah and the Daughters of Utah Pioneers. It lies on the East Bench of Spanish Fork located at Eighth East and Canyon Road and has become a local landmark. [8]

Top: Icelanders in native costume stand in front of the Iceland Monument during the 1938 “Iceland Days” celebration. Courtesy of La Nora Allred. Middle: The Icelandic Monument in Spanish Fork, Utah. Courtesy of David A. Ashby. Bottom: Cover of Centennial Anniversary Program of the First Icelanders to Utah in 1955. Courtesy of Fred E. Woods.

Top: Icelanders in native costume stand in front of the Iceland Monument during the 1938 “Iceland Days” celebration. Courtesy of La Nora Allred. Middle: The Icelandic Monument in Spanish Fork, Utah. Courtesy of David A. Ashby. Bottom: Cover of Centennial Anniversary Program of the First Icelanders to Utah in 1955. Courtesy of Fred E. Woods.

Two days before the dedication, the Deseret News announced that “girls representing each of the original pioneer families and dressed in native costumes will unveil the monument and Andrew Jenson, assistant Church Historian will offer the dedicatory prayer.” [9] On Thursday, August 4, 1938, the Spanish Fork Press reported, “With several thousand visitors swelling the population of Spanish Fork, and more than a 100 persons in colorful costume . . . the Icelandic Monument commerating [sic] the first permanent Icelandic settlement . . . was dedicated Monday evening.” [10] The following day, news of the historic event had already spread to the inhabitants of Iceland. Byron T. Geslison heard of the monument dedication via an Icelandic radio station when he was visiting with his cousin in Reykjavik in August of 1938. He noted that when the announcement was made, “It caused great interest among the people of Iceland.” [11]

Not only was there keen interest in the 1938 “Iceland Days” celebration, but nearly six decades later another festive occasion beckoned attention. In the summer of 1995 Einar Benediktsson, Iceland’s ambassador to the United States, visited the “Iceland Days” activities and spoke: “He described the Icelandic people as hardy, strong and intelligent and said those traits were shared by their descendants in Utah who are professional and Church leaders. ‘What a great heritage they have,’ he said.” Joining Ambassador Benediktsson on this occasion was Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who described the ambassador as “a man of great quality and character.” [12] Such meetings certainly helped to minimize the great chasm between Utah and Iceland.

1955 Centennial Anniversary of First Icelanders to Utah

Another key event that caught the attention of Icelanders on both sides of the ocean was the centennial anniversary of the first Icelanders to Utah, held June 15–17, 1955. The keynote speaker was Elder Henry D. Moyle of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Another guest speaker, Petur Eggerz, counselor to the Legislation of Iceland at Washington DC, officially represented his native Iceland. However, the most important attendees at the celebration were some of the early Icelandic immigrants themselves. One noteworthy person in attendance was the sole living child of Samúel Bjarnason, first male Icelandic immigrant to Utah. Bjarnason’s daughter, Mary Jane B. Nelson recalled the great effort her father put forth to succeed: “Father built a two-room adobe home on 2nd East and later built the two-story home in which I was born.” Mary Jane added, “Father was a forceful man and a very hard worker. He was up early and late and prospered because of it.” [13]

A float in the Spanish Fork parade, 1955. Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

A float in the Spanish Fork parade, 1955. Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

The performance of several prominent vocalists added a further dimension to the commemoration. A cultural highlight on the occasion was a demonstration of Icelandic wrestling known as “glíma,” performed by young wrestlers from Winnipeg who had come to participate in the festivities. [14] In addition, a parade was held with floats of Icelandic themes. Recently the author learned of photographic footage taken of the 1955 parade by Finnbogi Guðmundsson, who was then on a tour of Icelandic settlements in North America and had come to Utah to capture the “Iceland Days” festivities on film. [15]

Byron Geslison remembered: “This was a major event which attracted considerable attention, and was said to be the largest celebration Spanish Fork had had up to this time. The original Icelandic families were asked to make floats for the parade. These graphically portrayed the old country, the trek west by the pioneers, and various subsequent events.” [16] The Spanish Fork Press reported: “Seldom has Spanish Fork seen a celebration more enthusiastically accepted. . . . Every feature of the celebration was well attended. The pageant drew a capacity crowd with well over 1800 present. . . . Every Icelandic family assigned to build a float built one—without exception—a float their family could be proud of, and which would do credit to the whole Icelandic people.” [17]

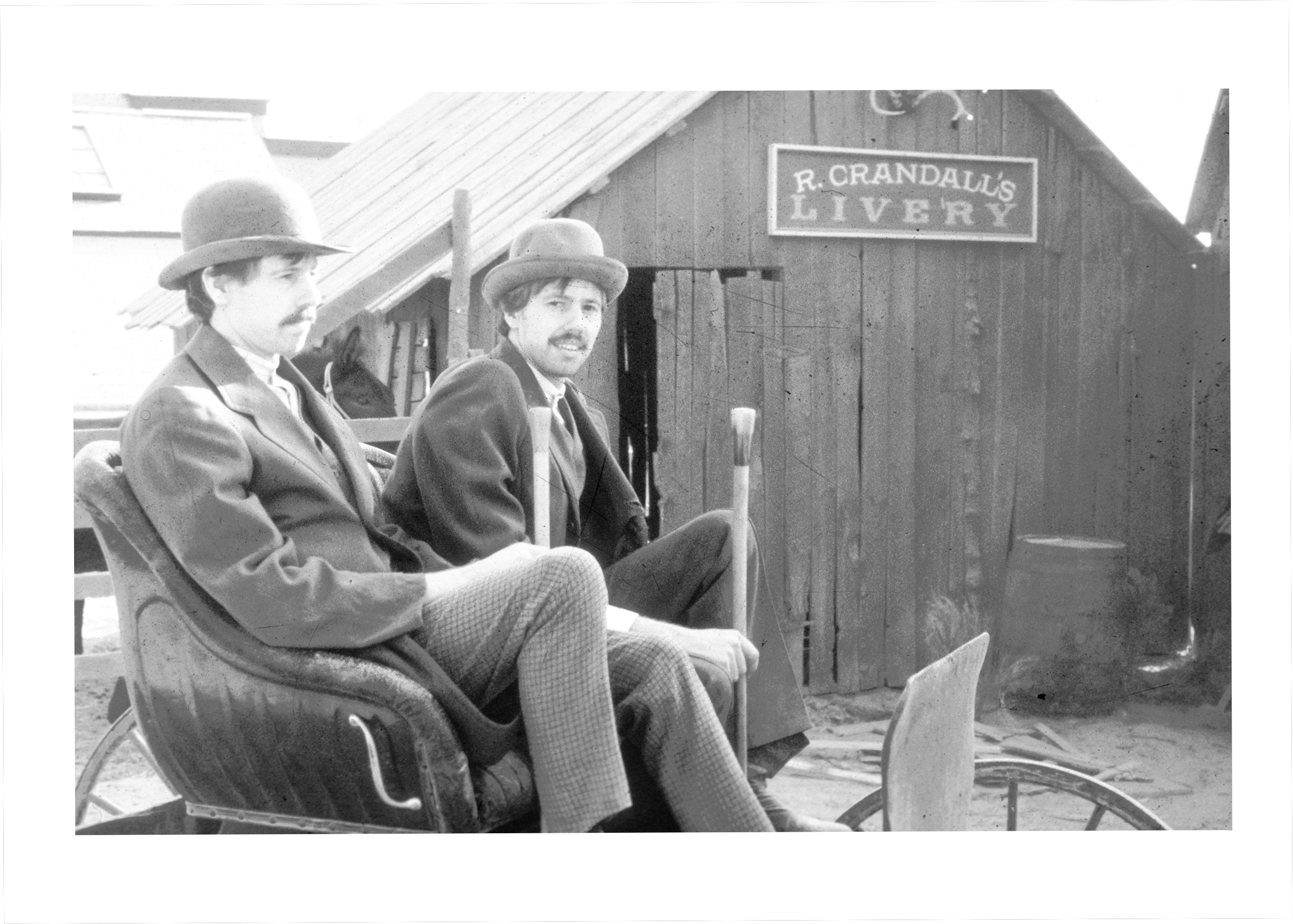

Daniel and David Geslison in the film Paradise Reclaimed. Courtesy of Daniel Geslison.

Daniel and David Geslison in the film Paradise Reclaimed. Courtesy of Daniel Geslison.

Key Events Unifying Utah and Iceland

Another episode that brought renewed interest in the Icelandic connection was the 1975 reopening of missionary work in Iceland by the Geslison family. [18] Upon their return from Iceland, the twin Geslison brothers David and Daniel participated in a five-hour film spotlighting the drama of LDS missionaries in Iceland. The 1981 film, based on the Halldór Laxness novel Paradise Reclaimed, revived interest in the topic of Iceland. [19]

Events occurring in Utah eventually influenced Icelandic politicians abroad. In 1989 Thor Leifson of Spanish Fork, was officially appointed the first honorary consul in the United States. [20] Thor’s father, Victor Leifson, had hosted Icelandic visitors to Utah until his death in 1983. Thor recounted that shortly after his father’s death, “I received a phone call from our U.S. Foreign Services in Washington D.C., and the gentlemen asked if it would be possible for me to entertain and host a dignitary from Iceland who was scheduled to come to the University of Utah.” Thor responded, “I asked the Foreign Service man how be obtained my name. . . . He was a bit evasive but mentioned he understood the Leifson family had assisted them this way before.” [21]

Thor Leifson served as the first honorary consul to Iceland. Courtesy of Thor Leifson.

Thor Leifson served as the first honorary consul to Iceland. Courtesy of Thor Leifson.

Thor further considered the possibility that perhaps the Icelandic government had records of several visits he had made to Iceland while traveling to Europe. In any case, this initial contact led to Thor’s hosting of other Icelandic dignitaries. Eventually Iceland’s ambassador, Ingvi Ingvarsson, suggested that Thor’s position become more official and that he receive the title of honorary consul of Iceland for the Intermountain area of the United States. Leifson explained, “For some years there had been a consular position in Denver, Colorado, but that the gentlemen there had recently passed away and Ingvi felt Salt Lake City was more central for the Inter-mountain area and therefore they would really like me to accept the assignment.” [22]

After a warm relationship was established between Leifson and Ingvarsson, the ambassador accepted Thor’s invitation for him and his wife to visit Utah. According to Leifson, this 1990 visit was a landmark event, as “no Icelandic ambassador had ever visited here before.” The visit was tailor made by Leifson to meet the interests of his Icelandic guests and to ensure that they saw the best of what Utah had to offer. The itinerary included a visit to several national parks, a BYU football game, a performance by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and a meeting with members of the Church’s First Presidency. [23]

The Utah visit was a great success. Leifson related, “The ambassador said he felt he related very well with the Mormon folk because they seem to have many of the same principles that Icelanders have, such as being hard working, conscientious, friendly, outgoing, highly literate and skilled workers.” Thor added, “He mentioned all these qualities that made him feel right at home here among the Mormon people.” [24]

In 1995 Clark T. Thorstenson of Provo, Utah, followed Leifson in his duties as consul. The stewardship of the Icelandic Consul to the western United States included the western states of Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, and Colorado. [25] During their years of service, these two Latter-day Saints hosted prominent Icelanders, including two presidents of Iceland, and arranged for the visit of several ambassadors from Iceland. Furthermore, they were successful in setting up meetings between Icelandic government officials and the First Presidency, as well as Utah governmental and congressional leaders such as Governor Michael Leavitt.

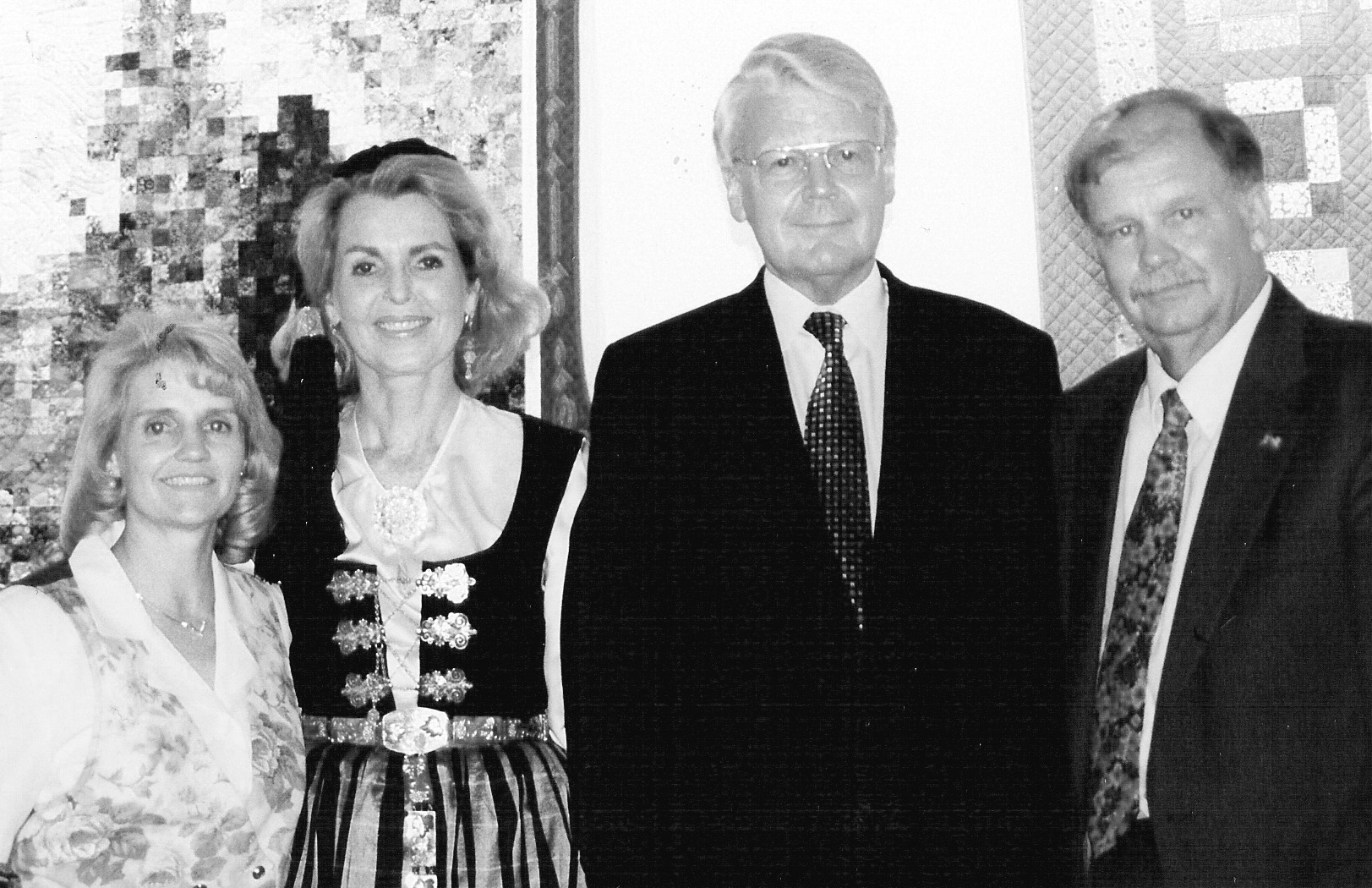

Clark T. and Colleen Thorstenson visit with Ambassador Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson. Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

Clark T. and Colleen Thorstenson visit with Ambassador Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson. Courtesy of David A. Ashby.

In December 1996 Consul Thorstenson extended a personal invitation to Iceland’s President, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, and his wife to visit Utah in 1997. This year marked the centennial of Spanish Fork’s “Iceland Days” as well as the sesquicentennial celebration of the Mormon pioneers entering the Salt Lake Valley. Grímsson and his wife enjoyed a weeklong July excursion that included visits with Church leaders and a Salt Lake City tour of Temple Square, the Church’s Welfare Square, and a broadcast of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s Music and the Spoken Word. They also visited the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah, where they dropped in on a class of missionaries learning Danish. The president conversed with them for several minutes in the Scandinavian language.

A special visit was also made to Spanish Fork, where President Grímsson and his wife saw evidence of its Icelandic roots. They rode in a horse-drawn buggy as they led the Fiesta Days parade as honored guests. When the parade concluded, the president visited the Spanish Fork Icelandic monument. Grímsson laid a wreath on the monument to honor the pioneer Icelanders. He and his wife then visited the Spanish Fork cemetery, where they viewed the graves of many Icelanders. Afterward, they toured historic Icelandic homes. [26]

Top: President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson and his late wife, Guðrun KatrinÞorbergsdóttir, in a horse-drawn buggy at the head of the Fiesta Days parade on July 24, 1997. Bottom: David A. Ashby, President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, and Guðrun Katrin Þorbergsdóttir at the Spanish Fork Cemetery looking at a grave of an early Icelandic immigrant, 1997. Photos courtesy of David A. Ashby.

Top: President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson and his late wife, Guðrun KatrinÞorbergsdóttir, in a horse-drawn buggy at the head of the Fiesta Days parade on July 24, 1997. Bottom: David A. Ashby, President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, and Guðrun Katrin Þorbergsdóttir at the Spanish Fork Cemetery looking at a grave of an early Icelandic immigrant, 1997. Photos courtesy of David A. Ashby.

In a “Pioneer Heritage Fireside,” held in Spanish Fork, President Grímsson extended a warm invitation to his fellow Icelanders to return for a visit to their fatherland: “My journey to your beautiful state . . . is also intended as an invitation to you all to return our visit by coming home to Iceland to worship in the land of your ancestors where the magnificent creation of the earth is still going on.” He added: “The soul of the Icelanders who came to Utah had been transformed by those forces. . . . I pay tribute to those pioneers and I salute their families who for so long have been true to the Icelandic tradition.” [27]

Several years after the impressionable Utah visit, President Grímsson, in a letter to Elder Wm. Rolfe Kerr, a General Authority, said, “One of the most memorable events of my presidency was the visit I and my late wife Guðrún Katrín made to Utah in 1997. It was a revelation to us to discover the strong and lively Icelandic heritage that still flourishes in the State of Utah and to meet the leaders of the Church.” [28]

Organized Tours to Iceland

In 1996 Thorstenson made arrangements for the first large organized group of Icelandic Latter-day Saint pioneer descendants to visit Iceland. The tour was led by Lil Shepherd, then president of the Icelandic Association of Utah, Inc. Simultaneously, Icelandic descendent Mark Geslison and the Brigham Young University Folk Music Ensemble presented several concerts on the mainland and on the Westmann Islands. In the summer of 1997, Shepherd escorted another group of Western Icelanders back to their homeland. Lil and her group made dozens of contacts with native Icelandic relatives they had never met before. These tours and the BYU concerts generated positive television, radio, and newspaper reports throughout the nation. [29]

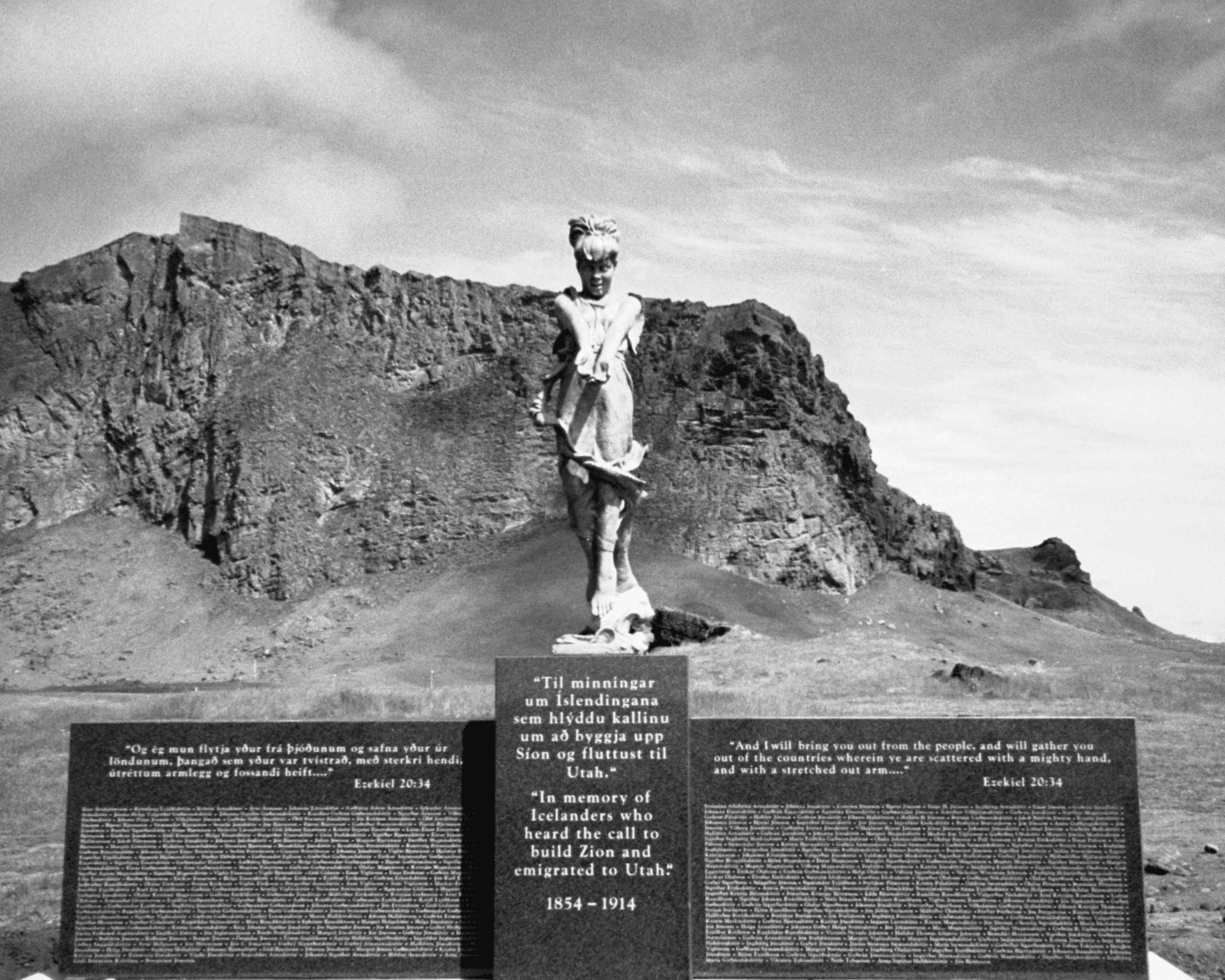

Top: Lil Shepherd, Guðrun Katrín Þorbergsdóttir, President Ólafur RagnarGrímsson, and David A. Ashby, 1997. Middle: President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson visits with President Gordon B. Hinckley and Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin on a trip to the United States in January of 2004. Bottom: The monument at Westmann Island, which was dedicated on June 30, 2000. Photos courtesy of David A. Ashby.

Top: Lil Shepherd, Guðrun Katrín Þorbergsdóttir, President Ólafur RagnarGrímsson, and David A. Ashby, 1997. Middle: President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson visits with President Gordon B. Hinckley and Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin on a trip to the United States in January of 2004. Bottom: The monument at Westmann Island, which was dedicated on June 30, 2000. Photos courtesy of David A. Ashby.

Shortly after the tour group returned home, President Grímsson and his wife arrived in Utah, hosted by Lil Shepherd. Arrangements were made for the Grímssons to meet Church leaders such as Elder Merrill J. Bateman, president of Brigham Young University, and Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Friendships were established, seeds were cultivated, and Icelandic soil was finally prepared for Latter-day Saints to enjoy a permanency in the land of fire and ice.

Historic Commemoration Project

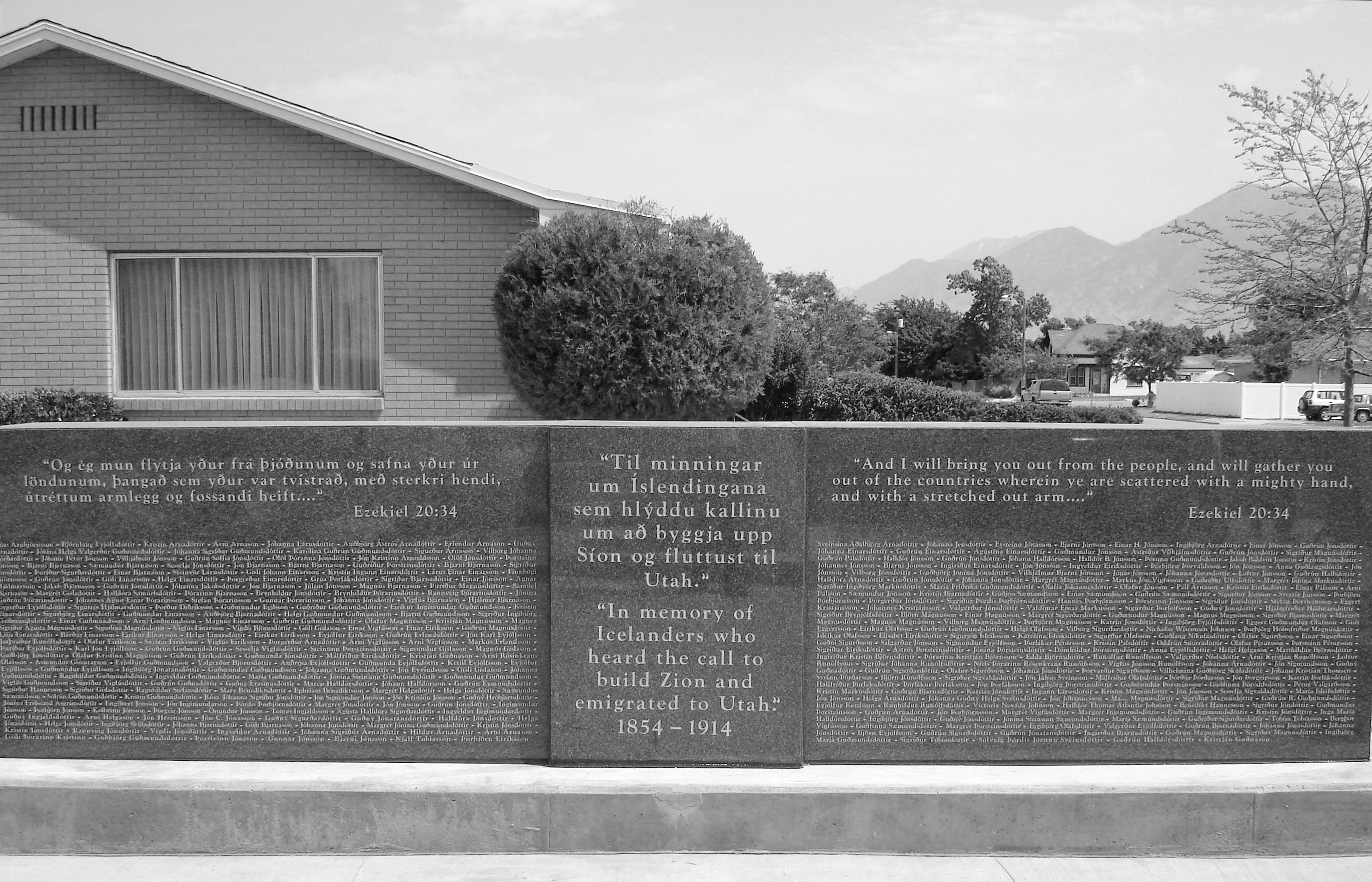

Three years later, on June 30, 2000, a cluster of Icelandic Saints from Utah and Iceland met to celebrate the erection of a monument on the Westmann Islands. This, “Monument to the Emigrants,” includes a sculpture titled The Messenger, by Utah artist Gary Price and presents the figure of an angel with outstretched hands to the sea, symbolizing the divine assistance these Icelandic emigrants received as they journeyed to Utah. The base of the monument also includes a biblical passage engraved in both Icelandic and English: “And I will bring you out from the people, and I will gather you out of the countries, wherein you are scattered, with a mighty hand, and with a stretched out arm” (Ezekiel 34:20). In addition, below this passage of scripture is a list of the names of 410 Icelanders who left their homeland for Utah between 1854 and 1914, about half of which were from the Westmann Islands. [30]

Those who were in attendance for this special occasion included not only friends and family of Icelanders who had immigrated to Utah but also Icelandic government officials and LDS Church leaders, Ólafur Einarsson, district president of the Church in Iceland, and Elder Kerr, then serving in the North European Area Presidency. Before dedicating the monument, Elder Kerr thanked the citizens of the Westmann Islands for their support in allowing the monument to be erected and also Church members who assisted with this project. He made special note of Spanish Fork citizen and Iceland’s honorary vice consul J. Brent Haymond, whom he thanked “for his tireless efforts in seeing the project through to completion.” Kerr further complimented Haymond, stating, “Brent’s gene pool does not accommodate the word ‘no.’” [31]

Top: Valgeir Thorvaldsson, Brent Haymond, and David A. Ashby at the signing of the Cooperative Tripartite Agreement on July 17, 1999, which led to the opening of “The Road to Zion” exhibit, launched in 2000 at the Hofsós Emigration Center. Courtesy of David A. Ashby. Bottom: Aerial photograph of Hofsós. The white arrow designates the location of the Icelandic Emigration Center. Courtesy of Valgeir Thorvaldsson.

Top: Valgeir Thorvaldsson, Brent Haymond, and David A. Ashby at the signing of the Cooperative Tripartite Agreement on July 17, 1999, which led to the opening of “The Road to Zion” exhibit, launched in 2000 at the Hofsós Emigration Center. Courtesy of David A. Ashby. Bottom: Aerial photograph of Hofsós. The white arrow designates the location of the Icelandic Emigration Center. Courtesy of Valgeir Thorvaldsson.

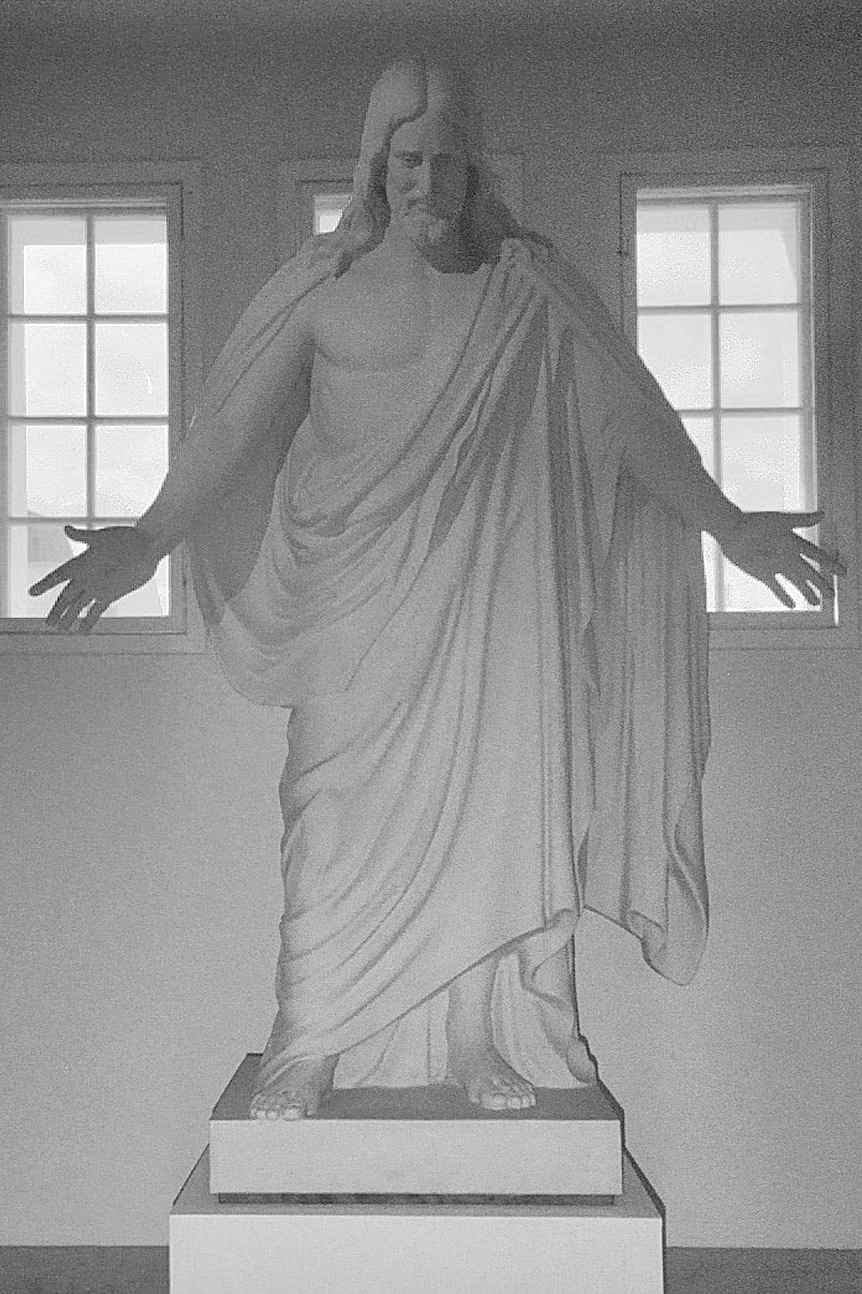

Just three days later (July 3, 2000), President Grímsson and a number of Icelandic Saints from Utah and Reykjavík gathered for the opening of a museum exhibit at the Icelandic Emigration Center in Hofsós, Iceland. This project had its origin with President Grímsson’s 1997 visit to Utah. Through this initial contact, a relationship began to develop between Valgeir Thorvaldsson, director of the Icelandic Emigration Center, and members of the Icelandic Association of Utah. This exhibit, titled “The Road to Zion,” featured a story of the Icelanders who gathered to Utah (mostly Spanish Fork) between 1854 and 1914. It included information about the first missionaries to Iceland, the journey by land and sea to Utah, as well their assimilation experience in a new country. The exhibit also included a statue of Jesus Christ. This statue is a smaller replica of a famous sculpture known as the Christus by Scandinavian sculpture Bertel Thorvaldsen (1768–1844), whose mother was Icelandic. [32]

Top: David A. Ashby, David Oddsson, Almar Grímsson, and Valgeir

Top: David A. Ashby, David Oddsson, Almar Grímsson, and Valgeir

Thorvaldsson, at the reopening of “The Road to Zion” exhibit in the Culture House in Reykjavík, Iceland, on May 7, 2005. Bottom: The Christus, by the famed Icelandic and Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1768–1844), which is part of “The Road to Zion ”exhibit being displayed at the Culture House in Reykjavík until 2007. Photos courtesy of David A. Ashby

The Icelandic Association of Utah rallied heroically to support these historic projects. [33] Throughout the undertakings, David A. Ashby, president of the Icelandic Association, and vice consul J. Brent Haymond spearheaded efforts to move plans forward in a timely manner. [34] Bliss Anderson, whom Ashby referred to as “our most active genealogist” in the Icelandic Association, labored diligently to provide names of the Icelanders who gathered to Utah, which were displayed on a “Wall of Honor” as part of the museum exhibit. [35] Since then, Bliss has continued to serve as a volunteer in the Spanish Fork Family History Center to help Utah citizens get connected with their Icelandic roots.

Bliss Anderson, local Spanish Fork genealogist, strives to put Utah Icelanders in touch with their roots. Courtesy of David A. Ashby

Bliss Anderson, local Spanish Fork genealogist, strives to put Utah Icelanders in touch with their roots. Courtesy of David A. Ashby

The Icelandic Connection in the Twenty-first Century

As the twenty-first century has commenced, a great relationship between Utah and Iceland continues. In the early spring of 2001, Iceland’s ambassador to the United States and Canada, Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson, and his wife, Bryndís Scram, visited Spanish Fork at the invitation of Brent Haymond. During the visit the ambassador was touched by a book compiled by Blaine Ashby and Bliss Anderson containing more than five hundred pages of his genealogy. [36] Later the ambassador wrote to Anderson, stating: “I shall cherish this royal present for as long as I live. . . . It is a treasure. . . . When the family gets together, this proud treasure is the focus of everyone’s attention.” [37]

A year later, Ambassador Hannibalsson returned to Utah for the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. During his visit, a reception was held for Icelandic athletes and dignitaries at the Springville Museum of Art near Spanish Fork. Spanish Fork Icelander Lil Shepherd and other organizers were expecting approximately two to three hundred visitors, but instead received over seven hundred. The tremendous support once again impressed the ambassador and thrilled the athletes. [38]

A Sesquicentennial Commemoration

President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson and Fred E. Woods discuss plans for the 2005 sesquicentennial event in Spanish Fork, Utah, 2004. Courtesy of Fred E. Woods.

President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson and Fred E. Woods discuss plans for the 2005 sesquicentennial event in Spanish Fork, Utah, 2004. Courtesy of Fred E. Woods.

In 2005 the Icelandic Association of Utah undertook a special project: a sesquicentennial commemoration of the first Icelanders to immigrate to Spanish Fork. The celebration was a remarkable success, lasting several days (Thursday through Sunday, June 23–26) and utilizing poetry, dance, and song throughout the events. One particular highlight was the unique music of the Icelandic Festival Choir, who stirred the hearts of listeners with several inspiring numbers. This forty-five-member choir financed their own travel in order to give tribute to the Western Icelanders of Utah. As usual, music was the magic which overcame language barriers in the conveyance of mutual affection and also obliterated any obstacles of misunderstanding which may have existed.

Top: Board of Trustees of the Icelandic Association of Utah. Back row (left to right): Krege Christensen, J. Brent Haymond, Richard Williams, G. Blaine Ashby, Jack Tobiasson, Richard Johnson. Middle row: Marilyn Ashby, Kathleen Reilly, Bliss K. Anderson, Rhea Jean Hancock, Vina J. Foster, Lil J. Shepherd. Front row: Cory Stone, David A. Ashby, Phyllis H. Ashby, Kristy Robertson, Art Johnson. Not shown: Kami Anderson, DeVon Koyle. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah. Middle: Members of the Sesquicentennial Celebration Committee. Back row (left to right): J. Brent Haymond, Richard Williams, Jack Tobiasson, Richard Johnson. Front row: David A. Ashby, Thora Leifson Shaw, Kristy Robertson, Paul Christensen. Not present: Susan B. Huff, DeVon Koyle. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah. Bottom: The monument in Spanish Fork, Utah, is similar to the monument at the Westmann Islands and lists the 410 Icelanders who made their way to Utah between 1854 and 1914. Courtesy of Derek J. Tangren, Mormon Historic Sites Foundation.

Top: Board of Trustees of the Icelandic Association of Utah. Back row (left to right): Krege Christensen, J. Brent Haymond, Richard Williams, G. Blaine Ashby, Jack Tobiasson, Richard Johnson. Middle row: Marilyn Ashby, Kathleen Reilly, Bliss K. Anderson, Rhea Jean Hancock, Vina J. Foster, Lil J. Shepherd. Front row: Cory Stone, David A. Ashby, Phyllis H. Ashby, Kristy Robertson, Art Johnson. Not shown: Kami Anderson, DeVon Koyle. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah. Middle: Members of the Sesquicentennial Celebration Committee. Back row (left to right): J. Brent Haymond, Richard Williams, Jack Tobiasson, Richard Johnson. Front row: David A. Ashby, Thora Leifson Shaw, Kristy Robertson, Paul Christensen. Not present: Susan B. Huff, DeVon Koyle. Courtesy of the Icelandic Association of Utah. Bottom: The monument in Spanish Fork, Utah, is similar to the monument at the Westmann Islands and lists the 410 Icelanders who made their way to Utah between 1854 and 1914. Courtesy of Derek J. Tangren, Mormon Historic Sites Foundation.

Those attending the Friday night Spanish Fork gala were impressed by the heartfelt remarks delivered by President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson. He publicly admitted that initially Icelanders felt enmity towards the early Mormons because their conversion represented the first religious rebellion in eight hundred years. Their migration was also resented because they left at a precarious time when Icelanders were fighting the Danes for national independence. President Grímsson explained that due to the sincere efforts initiated by Utah Icelanders to reconnect with their homeland and to keep their cultural heritage vibrant, reconciliation had melted the icy feelings of the past and that goodwill presently flourishes. He complimented: “You have given us a pride in this joint heritage we share. . . . We hope we will enjoy your friendship forever.”

President Grímsson addressed a large assembly the following day at the dedication services held at the Icelandic Memorial in Spanish Fork. In his remarks he petitioned the audience to reflect upon the faith of the poor Icelandic farmers and fishermen who left their homes for a new country and to consider the great legacy they have subsequently left in Spanish Fork. He graciously thanked the Icelandic Association of Utah, the LDS Church, and most especially President Gordon B. Hinckley for their support of the Icelandic people. Grímsson concluded with telling the audience that this new Icelandic monument containing the names of 410 Icelandic immigrants (1855–1914) along with her sister monument on the Westmann Islands, “reminds us that we share the same heritage. We are one family in spirit, in faith, in heritage and in vision.”

Following these beautiful sentiments by President Grímsson, President Hinckley was invited to speak before dedicating the additions to the Icelandic memorial. These new acquisitions included a large rock taken from the area used for baptisms on the Westmann Islands, two new flags representing the United States and Iceland, eight plaques detailing the early history of Latter-day Saint Icelanders and the beautiful granite monument engraved with the names of the Icelandic immigrants. [39] President Hinckley pointed out that President Grímsson had bestowed a great honor upon those assembled by coming so far to pay tribute to the early Icelandic Utah pioneers. After recounting highlights of the sesquicentennial history of the Latter-day Saint Icelanders, he reminded the audience that the first Icelanders who gathered to Utah took ten months to make the journey, while he had made the same trip three years earlier in just twelve hours. He also recollected that he knew of no other LDS ethnic group who had kept their heritage in tact as well as the Icelanders had. The attendance of both President’s Hinckley and Grímsson on this special sesquicentennial occasion and the uniting of their hands in friendship served to symbolize the powerful brotherhood which is presently enjoyed by Icelanders at home and abroad in Utah.

Top: President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson shaking hands with those who gathered for the dedication of the Icelandic monument on July 25,2005. Courtesy of Derek J. Tangren. Bottom: President Grimsson and President Hinckley standing together at the sesquicentennial commemoration. Courtesy of Ethan Vincent.

Top: President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson shaking hands with those who gathered for the dedication of the Icelandic monument on July 25,2005. Courtesy of Derek J. Tangren. Bottom: President Grimsson and President Hinckley standing together at the sesquicentennial commemoration. Courtesy of Ethan Vincent.

In this, the twenty-first century, Icelandic converts as well as all other international converts are counseled to remain in their homelands and strengthen their local congregations. [40] Church members are also encouraged to be exemplary citizens in each of their respective countries. [41] But the Icelandic Saints who were once asked to forsake their beloved island and to build new lives in this aforetime inhospitable western desert somehow managed to instill devotion to loved ones left behind and a fierce loyalty to their beloved homeland of fire and ice. The posterity of these noble Atlantic pioneers continues to maintain their Icelandic identity and nurture their family ties across the great deep. Many are still active in the Icelandic Association of Utah and gather annually for “Iceland Days” and other activities. Others are involved in the Regional Family History Center at Spanish Fork and have been especially aided by the untiring dedication of local genealogist Bliss Anderson, who strives to connect Utah Icelanders with their roots. [42]

Top: A portion of 45 members of the Selfoss, Iceland, Choir who paid their own expense to come to Utah for the commemoration.

Top: A portion of 45 members of the Selfoss, Iceland, Choir who paid their own expense to come to Utah for the commemoration.

Courtesy of David A. Ashby. Bottom: Melva, Daniel, and David Geslison (left to right) standing at the sesquicentennial commemoration when President Hinckley asked if the Geslison family were in the crowd, 2005. Courtesy of Ethan Vincent.

At this time of reflection in this sesquicentennial year one is compelled to acknowledge that the establishment of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the land of fire and ice and the subsequent travels to Zion was no small feat for the hardy participants. Assimilation for transplanted Icelanders on American soil required suitable time for absorption. Seeds from the fatherland have germinated in this western garden, and these Utah vines have sprouted and climbed back to their homeland northward. Joyfully, the roots have welcomed the good fruit, and a spiritual grafting has been realized.

If the past is any indication of the future, many more celebrations of the rich Icelandic heritage flourishing in Spanish Fork will yet be enjoyed. Reciprocally, Icelandic commemorations will also remind native Icelanders of their friends and family in Utah, who are ever mindful of them. Finally, this inspirational story bears eloquent witness that the Great Husbandman is keenly aware of each portion of His garden and that He truly does remember those who are upon the isles of the sea.

Michael L. Hutchings, secretary of the Mormon Historic

Michael L. Hutchings, secretary of the Mormon Historic

Sites Foundation, looks on as Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson,

president of Iceland, and Gordon B. Hinckley, president of

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, shake

hands. Courtesy of Deseret Morning News.

Painting honoring the Icelandic Sesquicentennial Commemoration. Courtesy of the artist, Calvin Jolley.

Painting honoring the Icelandic Sesquicentennial Commemoration. Courtesy of the artist, Calvin Jolley.

Notes

[1] La Nora Allred, The Icelanders of Utah (reprint, Spanish Fork, UT: Icelandic Association, 1998), 39.

[2] David A. Ashby, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah,” 10, indicates that the Icelandic Association also began to hold an annual Thorablot gathering in March 1998. Ashby explains this festive occasion: “Mid-winter is marked in the Icelandic calendar as the time of Thorri—known since the 12th century as the fourth month of the cold season. Blot is a feast that is held many times a year. Thorrablot is held at the end of winter or the end of the coldest season in Iceland.”

[3] David A. Ashby, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah,” unpublished paper in author’s possession, 7.

[4] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 39.

[5] Byron T. Geslison, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah” (adapted from a speech given to the Provo Chapter of the Utah Historical Society, March 11, 1992). This unpublished article is in the author’s possession.

[6] Joseph Walker, “Icelanders: ‘Something to Be Proud Of,’” Church News, August 12, 1984, 9.

[7] “Icelandic Memorial Day,” Deseret Evening News, August 4, 1900, 7. In an article titled “Funeral Services for Rev. R. Runolfson,” Spanish Fork Press, January 24, 1929, 1, we learn that Runolfson had immigrated to America in 1881. He also returned to Iceland to fill a pastorate for a decade (1906–16) before returning to Spanish Fork. He spent a total of thirty-five years as pastor of the Lutheran Church in Spanish Fork and died January 23, 1929, at the age of 76.

[8] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 40–41; LeRoy Whitehead, “Icelandic Converts Honored,” Deseret News, July 30, 1938, 2.

[9] LeRoy Whitehead, “Icelandic Converts Honored,” Deseret News, July 30, 1938, 2. “Icelandic Pioneers of Utah Are Honored,” Deseret News, August 2, 1938, 3, reported two days after the event that Andrew Jenson reviewed some of the early history of Iceland before offering the dedicatory prayer. In the “Journal of Andrew Jenson, 1850–1941,” for the date of August 1, 1938, Church Archives, Jenson writes: “Mon, Aug. 1. . . . Left the city by auto at 5pm. with Bertha and others and traveled to Spanish Fork where we attended a celebration honoring the arrival of the first Icelanders to Spanish Fork. I dedicated the beautiful monument erected by the local Saints and also made a speech. Clarence G. Nealen represented Gov. Blood and there was quite a lengthy program.” Appreciation is expressed to Derek Tangren for transcribing this entry from Jenson’s journal.

[10] “Monument to Early Settlers Dedicated,” Spanish Fork Press, August 4, 1938, 1. On this same page, an article titled “Observe Icelandic National Holiday” reports, “With approximately 2,000 persons in attendance, most of them of Icelandic descent, the fortieth annual Icelandic National holiday to be held here was celebrated . . . at the Arrowhead Resort near Benjamin.”

[11] Byron T. Geslison, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah,” 17, 22.

[12] Greg Hill, “Iceland Day Preserves Settlers’ Heritage,” Church News, August 12, 1995.

[13] “Icelandic Descendants Hold Fete,” Deseret News, June 17, 1955, 10A.

[14] Allred, The Icelanders of Utah, 41.

[15] Finnbogi Guðmundsson, Nineteen Articles and Speeches (Reykjavík: University of Iceland, 2003), 6, evidences that at this time Finnbogi was serving as an associate professor of Icelandic Language and Literature at the University of Manitoba. He later served as the director of the National Library of Iceland (1964–94). Thanks is expressed to David A. Ashby for bringing this information to my knowledge.

[16] Byron T. Geslison, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah,” 18.

[17] “Congratulations Offered for Centennial Success,” Spanish Fork Press, June 23, 1955, 1.

[18] Byron T. Geslison, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah,” 18.

[19] Golden A. Buchmiller, “Paradise Reclaimed,” Church News, March 28, 1981, 1.

[20] Thor Leifson, Sagas of My Life, 59. A bound, unpublished, and undated autobiographical account in Thor Leifson’s possession. According to the Autobiographical Sketch of Thor Leifson, Icelandic Memories, vol. 1, compiled by Phyllis H. Ashby and in possession of the Icelandic Association or Utah (n.p, n.d.), he was asked to be the honorary consul in 1987, but as noted in Leifsons’ Sagas of My Life, 59, the official letter of appointment did not arrive until 1989.

[21] Leifson, Sagas of My Life, 58.

[22] Leifson, Sagas of My Life, 58, 60.

[23] Leifson, Sagas of My Life, 60.

[24] “LDS Leaders, Visitors: ‘Friendly Exchange,’” Church News, October 27, 1990, 5.

[25] Autobiographical Sketch of Clark T. Thorstenson, Icelandic Memories, vol.1. Leifson, Sagas of My Life, 60, reveals that Thor Leifson’s consular appointed ended when he was called with his wife to serve as missionaries in the Swiss Temple.

[26] Gerry Avant, “Iceland President Visits Utah,” Church News, August 2, 1997, 3,13.

[27] Avant, “Iceland President Visits Utah,” 13.

[28] Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson to Wm. Rolfe Kerr, January 26, 2000. A copy of this letter is in the author’s possession.

[29] Oral interviews with Clark T. Thorstenson on July 10, 2001, and David A. Ashby on July 11, 2001.

[30] “Journal of Historical Events June 30 to July 4, 2000,” pamphlet published by the Icelandic Association of Utah, Spanish Fork, 2000, 2.

[31] “Journal of Historical Events June 30 to July 4, 2000,” 5. Another catalytic individual involved with the monument project was David A. Ashby, who was then serving as the president of the Icelandic Association of Utah.

[32] “Journal of Historical Events June 30 to July 4, 2000,” 8–9. This pamphlet also indicates that Arni Pall Johannsson was in charge of the design of the exhibit and that he was assisted by Marjorie Conder, staff member of the LDS Museum of Church History and Art (Salt Lake City) as well as her colleague Kevin Neilson, who journeyed to Iceland to assist with the exhibit’s implementation. In 2004 this exhibit was transported to Reykjavík. On May 7, 2005, the exhibit reopened at the Culture House, where it will be displayed until 2007.

[33] Church Almanac, 2001–2002 (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2002), 341.

[34] The wife of David (Bonnie Ashby) and Brent’s spouse (Janice Ashby) have been a continual support to their husbands in this 2000 project and continue to support them in their work to preserve a bond between Iceland in Utah. In the summer of 1999, Brent Haymond (vice consul), David Ashby (president of the Icelandic Association) met with Valgeir Thorvaldsson (director of the Icelandic Emigration Center of Hofsós) and Sigríður Sigurðardóttir (director of the Skagafjörður Folk Museum in Glaumbær) met in Iceland to discuss the proposed “Road to Zion” exhibit. On July 17, 1999, Thorvaldsson, Sigurðardóttir and Ashby signed a “Cooperative Tripartite Agreement between these three organizations to “strengthen the ties that exist between these institutions by attempting to independently and together to preserve and research the culture and heritage of the Icelandic immigrants and their descendants.” This agreement is in David Ashby’s possession. In February 2000, my wife was reading the local newspaper announcing plans for this “Road to Zion” exhibit. Due to my previous focus on immigration research as well as her intuition, she told me that she felt I should be involved with the project. This comment has led to my five-and-a-half year involvement with Icelandic Latter-day Saint research.

[35] July 6, 2000, oral interview with David A. Ashby. Ashby served as the president of the Icelandic Association of Utah, Inc. from 1994–95 as well as 1999–2000. He is currently serving as the director of Iceland relations in the Association.

[36] “Iceland’s Ambassador visits Sp. Fork,” Spanish Fork Press, April 12, 2001, 5.

[37] “Icelandic Olympic Reception Draws Crowd,” Daily Herald (Provo), February 27, 2002, 1.

[38] “Icelandic Olympic Reception Draws Crowd,” 1.

[39] The memorial site also has new landscaping, which adds a renewed beauty to the lighthouse monument erected in 1938. On June 26, 2005, David A. Ashby told me that in a recent interview he had with Deseret News reporter Roger Harding, David mentioned that there was symbolism behind the lighthouse that most visitors viewed as merely a reminder of the seafaring nature of the Icelandic people. However, Ashby added that to him it also represented the Light of Christ, which not only holds the Icelanders of Utah with the people of their homeland but also all of God’s children spread throughout the earth.

[40] On December 1 the First Presidency issued the following statement: “We wish to reiterate the long-standing counsel to members of the Church to remain in their homelands rather than immigrate to the United States. As members throughout the world remain in their homelands, working to rebuild the Church in their native countries, great blessings will come to them personally and to the Church collectively” (Church News, December 11, 1999, 7).

[41] As previously noted, the Articles of Faith are part of the Latter-day Saint scriptures. Article 12 states: “We believe in being subject to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates, in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.”

[42] This center is owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1995 Clark T. Thorstenson was instrumental in arranging to have the Icelandic genealogical materials transferred from the Family History Center in Salt Lake to the Regional Family History Center in Spanish Fork, a very important source for this topic of study. Phylis and Marilyn Ashby, both members of the Icelandic Association of Utah, have compiled several volumes of textual and photographic materials that highlight the history of the Icelandic history of Spanish Fork and provide biographical sketches of hundreds of Icelanders in this region. In 1995 an article titled “Icelandic Historian Receives Annual ‘Heritage Award,’” Spanish Fork Press, August 10, 1995, 8, indicates that Phylis, who had begin serving as the Icelandic Association historian since 1987, was the recipient of the annual Icelandic Heritage Award. It also notes that Phylis would be passing on the job of historian to Marilyn but would still be of assistance if needed. David A. Ashby, “The Icelandic Settlement in Utah,” 18, estimates that nearly 100,000 descendants have come from the original 410 Icelanders who immigrated to Utah between 1855 and 1914, but he notes that they are now scattered across America and in other parts of the world.