The Winepress

Jennifer C. Lane, “The Winepress,” in Finding Christ in the Covenant Path: Ancient Insights for Modern Life (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 119‒28.

I was in elementary school when the Washington D.C. Temple was built. It was the first temple east of the Mississippi River and is prominently situated on a hilltop along the Beltway, the major thoroughfare encircling Washington, D.C., and Arlington, Virginia: my home. I don’t remember my exact age, but I clearly remember one Saturday morning when my parents explained that they were going to the temple open house and that I could join them. In a moment that I continue to regret, I told them that I didn’t want to miss my favorite Saturday-morning cartoon shows. I wasn’t interested in their invitation. They didn’t force me, and I didn’t go.

Sometimes there is a flip side to the invitations that we are offered. If we don’t choose to receive the gift that we are being given, then the gift itself can stand in condemnation of our choice. Speaking of the last resurrection, Christ says that those who never chose to know him will come and stand before him. “And then shall they know that I am the Lord their God, that I am their Redeemer; but they would not be redeemed” (Mosiah 26:26)—“would not” meaning “did not want to.” These will be the people who had the opportunity to come to know Christ and receive his redeeming power but who did not want to be redeemed. The consequences of agency can be sobering and sound harsh, but remembering that we receive what we are willing to receive helps us realize that Christ is always seeking our redemption (see Doctrine and Covenants 88:32–33). He is always offering us mercy. His arms of mercy are extended to us. But his justice—his righteousness—is shown in letting us have the final word on what we want.

Keeping this perspective can help us understand the imagery of Christ and the winepress. In Isaiah 63 we see both the loving and the more sobering aspects of this image. In this prophecy, Christ is asked, “Wherefore art thou red in thine apparel, and thy garments like him that treadeth in the winefat?” (63:2). From modern-day scripture, we know that when he comes again “the Lord shall be red in his apparel, and his garments like him that treadeth in the wine-vat” (Doctrine and Covenants 133:48). In Isaiah we read that, when asked about his red garments, he shall say: “I have trodden the winepress alone; and of the people there was none with me: for I will tread them in mine anger, and trample them in my fury; and their blood shall be sprinkled upon my garments, and I will stain all my raiment” (Isaiah 63:3). The language here of the Lord’s anger and fury can be hard to reconcile with the gospel message of his redeeming love. His Second Coming is also associated with judgment, and I think that we can see his role as judge and our personal accountability to him in better perspective as we dive more deeply into the imagery of Christ treading the winepress alone.

The idea of Christ as the mystical winepress was an image that was beloved in the later Middle Ages. As Christians tried to think about what the Lord’s Atonement meant and how they could receive it in their lives, they knew that the sacrament, what they knew as the Eucharist, was essential. The Eucharist, the body and blood of Christ, was sacred, and they experienced partaking of it, or even seeing it, as a very holy occasion. Indeed, as time went on it became common for only priests to drink the wine, and ordinary Christians began to partake of the bread (the host) less frequently because it was seen as so holy that they feared not being worthy. At the very same time, the holiness and power in these substances was the source of widespread meditation and reverence. People tried to understand how Christ could make himself present in these substances, and they developed artistic metaphors to depict Christ as the mystic mill and the mystical winepress to show that from his body came the substances that could give spiritual life.

The imagery of Christ treading the winepress, as we have seen, has a clear foundation in the imagery of Isaiah, and this biblical image can be helpful to think through what these medieval images might be pointing us to. Through metaphors of physical reality, we can get a greater glimpse into spiritual reality. Indeed, the very physical reality of the pressing of olives seems to have stood behind the significance of Christ’s suffering in a place called Gethsemane, which literally means “oil press.” When olives are first pressed for oil, the initial pressing has a reddish color, reminiscent of Christ’s bleeding from every pore in the garden.

Encouraging us to reflect on this symbolism whenever we see olive oil used for a blessing, President Russell M. Nelson remarked around thirty years ago: “Remember what it meant to all who had ever lived and who ever would yet live. Remember the redemptive power of healing, soothing, and ministering to those in need. Remember, just as the body of the olive, which was pressed for the oil that gave light, so the Savior was pressed. From every pore oozed the life blood of our Redeemer. And when sore trials come upon you, remember Gethsemane.”[1] By slowing down to see the physical substance of olive oil as a symbol for the atoning blood of Christ, we can begin to see the spiritual truth of Christ’s suffering and death as the source of healing and life.

The image of Christ being pressed in a winepress showed his sufferings as the source of the life and mercy that we need. Theodosia-altaar, detail, 1545. Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht.

The image of Christ being pressed in a winepress showed his sufferings as the source of the life and mercy that we need. Theodosia-altaar, detail, 1545. Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht.

The Lord has always used images and parables to connect physical reality with spiritual reality. Just as the pressing of olives points to the pressing of Christ, so Isaiah used the pressing of grapes to help us understand Christ’s suffering. Following this metaphor, in late medieval devotional images of Christ, we can see him standing in a vat of grapes, stomping them to produce wine, but at the same time Christ himself is being pressed and is bleeding. Sometimes it is the cross alone that presses on him and sometimes a press is depicted above his head pressing on the cross that presses on him. Often depicted as a press that turned on a screw, like a very old-fashioned printing press, these images portrayed Christ being pressed down in his suffering and his blood merging with the wine produced as he trod the winepress. Even in some depictions of Christ as a child on his mother’s lap, he or Mary is portrayed holding a bunch of grapes, pointing ahead to his atoning sacrifice.

In our days, we use water in the sacrament rather than wine, and so the visual parallels of wine and Christ’s blood take more imagination than in earlier Christian days. Fortunately, the sacrament hymns can help focus our meditation. Again, “Reverently and Meekly Now” encourages us to see beyond the bread and water to the spiritual truths presented with the physical realities.

In this bread now blest for thee,

Emblem of my body see;

In this water or this wine,

Emblem of my blood divine.

Oh, remember what was done

That the sinner might be won.

On the cross of Calvary

I have suffered death for thee.[2]

Looking for and seeing the redeeming sacrifice of Christ in physical symbols may take effort, but our effort allows us to behold and feel the love manifest in his gift.

We can see how early the imagery of wine as blood appears by examining the Gospel of John’s description of the Savior’s first miracle. In this account of Christ turning water to wine at Cana, the water becoming wine provides an important religious contrast. The water that Christ turned into wine was not just any water but was water used for ritual purification following an understanding of the law of Moses. Christ used the water found in “six waterpots of stone, after the manner of the purifying of the Jews” (John 2:6). So the external purification mandated by the law of Moses stands in contrast to the foreshadowed inner purification offered by Christ’s atoning blood, symbolized by the wine.

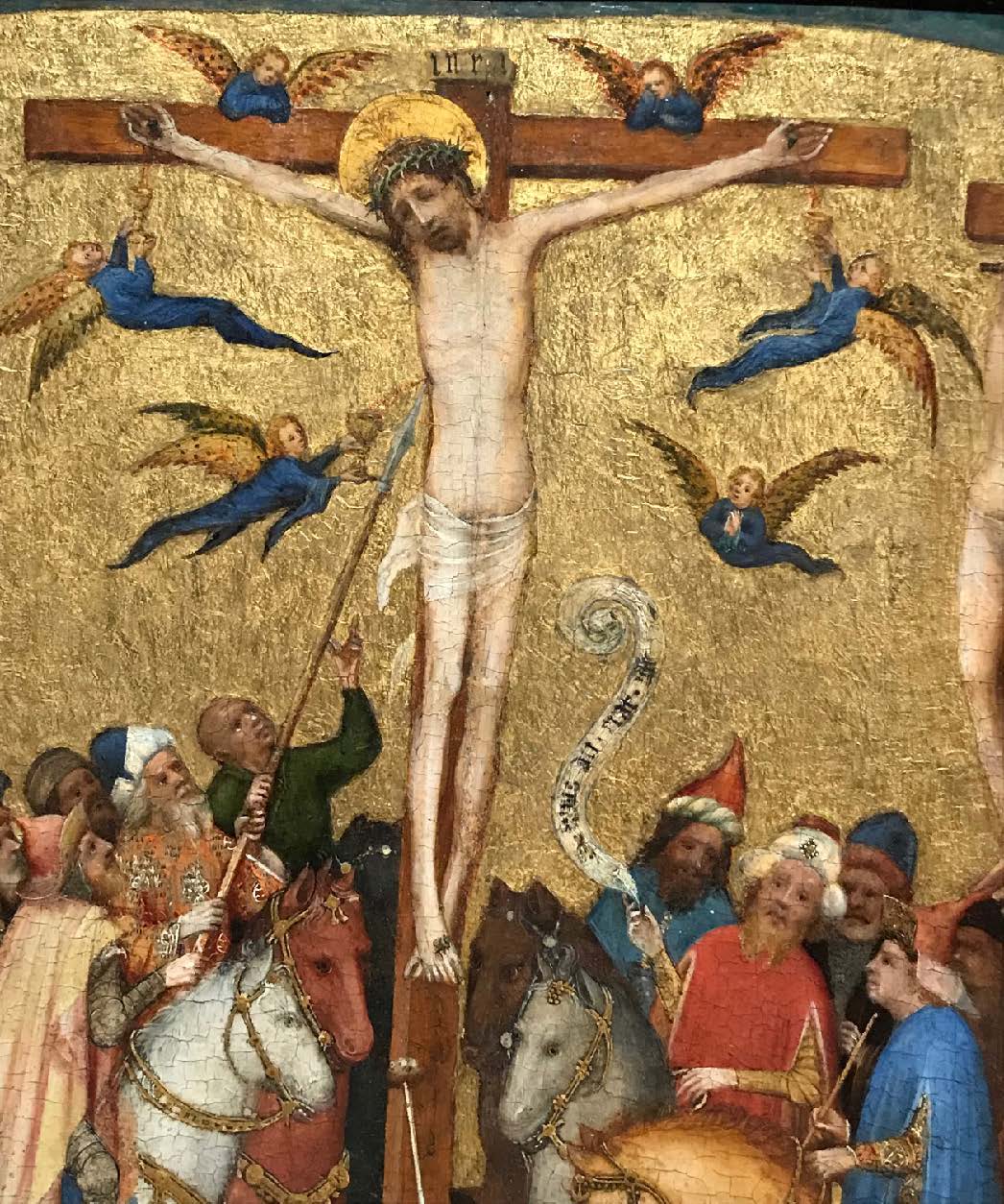

Angels were often shown collecting the blood of Christ that would nourish the faithful. Meister der hl. Veronika, The Small Calvary, detail, around 1400.

Angels were often shown collecting the blood of Christ that would nourish the faithful. Meister der hl. Veronika, The Small Calvary, detail, around 1400.

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln.

Christ’s first miracle points to and foreshadows the purpose of his mission of redemption. Through his suffering and death, he came to provide a means of holiness and sanctification that will replace the external holiness made available “after the manner of the purifying of the Jews.” Through his atoning blood, we can have our garments made white; we can become clean. But to see this dimension of what the miracle teaches, we must connect the images of wine and blood in our own minds, as the early Christians—the first readers of the Gospel of John—would have done.

In the later Middle Ages, making the connection between wine and blood was not difficult. Often the images of Christ as the mystic winepress show individuals, either angels or clergymen, holding up the sacramental chalice or cup filled with the wine that was the final result of the “processing” of this mystic winepress. Similarly, many depictions of Christ on the cross also show one or more angels hovering in the air, holding a chalice to gather the blood from Christ’s hands or side. There was no question for medieval believers that Christ bled to provide the blood that would nourish the faithful.

Another beloved medieval image that reinforced this metaphor of Christ’s blood giving life to the faithful was the legend of the pelican. There were medieval books known as bestiaries that had fanciful descriptions of legendary animals. The pelican was one of these animals. I learned about this legend when I sang in the BYU Women’s Chorus before my mission. The composer, Randall Thompson, had set an entry of one of these bestiaries to music in a beautiful song, “The Pelican,” with English text by the poet Richard Wilbur. It wasn’t just the stirring musical setting or the evocative language of the translation that moved me. In this song, I came to see and feel another dimension of the love of God.

In the legend the pelican takes care of its offspring, but in return they attack their parent and die as a result. The pelican then strikes its own breast with its beak and with the blood that flows out brings the children back to life. Throughout the Middle Ages, the power of self-sacrifice in the image or symbol of the pelican was repeatedly drawn or sculpted to point to Christ. This metaphor of Christ giving his own life to give new life to his offspring, the believers, joined the symbol of the mystic winepress as an extremely widespread and beloved image of Christ’s redeeming blood.

The legend tells how the pelican brought its young back to life by striking its own breast with its beak. Sint-Niklaaskerk, embroidery on processional canopy. Veurne, Belgium.

The legend tells how the pelican brought its young back to life by striking its own breast with its beak. Sint-Niklaaskerk, embroidery on processional canopy. Veurne, Belgium.

Judgment and the Winepress

Both Isaiah and the book of Revelation connect the winepress with the wrath of God. We sometimes see that wrath pointed against us, but let’s look more closely at the language in Revelation 19. Here we see Christ coming to rule and reign. He is “clothed with a vesture dipped in blood: and his name is called The Word of God” (19:13). Verse 15 points to his right to judge and rule: “and out of his mouth goeth a sharp sword, that with it he should smite the nations: and he shall rule them with a rod of iron.” But it also stresses that “he treadeth the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God.”

Recognizing that the winepress was “the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God” is a critical point that we sometimes overlook. The consequences of our sins result in what scripture describes as the “wrath of God.” To use another image, this winepress is the bitter cup that should have been ours, but Christ drank it for us. At the temple at Bountiful, directly after announcing himself as Jesus Christ, “the light and the life of the world,” Christ tells the people: “I have drunk out of that bitter cup which the Father hath given me, and have glorified the Father in taking upon me the sins of the world, in the which I have suffered the will of the Father in all things from the beginning” (3 Nephi 11:11). Drinking this cup of wrath for us, “treading the winepress alone,” this is what he is offering to take from us. His willingness to tread the winepress, to drink the bitter cup, also shapes the meaning of the cup that he gives us to drink.

Christ takes the cup of wrath, the cup of indignation. By drinking the bitter cup of the consequences of all that we have done to offend God, Christ frees us from what should have been our fate. He partakes of the consequences of our life and offers us instead the chance to partake of his life, to enjoy his unity with the Father and the fullness of his Spirit. The bitterness of all that we have chosen did not just disappear. He drank that bitter cup in our place. What Christ has done in treading the winepress as he suffered for our sins puts us in a relationship with him that we cannot ignore.

And so, as we read the passages about Christ treading the winepress alone, hopefully we can see the price that he paid in treading “the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God” (Revelation 19:15). He doesn’t just want us to feel sorry for him. He wants us to know that his love is so deep that, like the legend of the pelican, he shed his blood to give us life. He wants us to know that his love is so deep that he would do anything to keep us from receiving the eternal consequences of our choices. “Thus saith thy Lord the Lord, and thy God that pleadeth the cause of his people, Behold, I have taken out of thine hand the cup of trembling, even the dregs of the cup of my fury; thou shalt no more drink it again” (Isaiah 51:22). As he treads the winepress alone, he is pleading with us to accept his suffering on our behalf. That is what he wants for us more than anything else. He wants us to “no more drink” the cup of trembling and the cup of God’s wrath.

How could he more fully communicate his desire to redeem us? “I have trodden the winepress alone; and of the people there was none with me” (Isaiah 63:3). None could be with him because he did this for all of us. As Abinadi testified, “Thus all mankind were lost; and behold, they would have been endlessly lost were it not that God redeemed his people from their lost and fallen state” (Mosiah 16:4). The redemption price was paid, and Christ will return in a red robe so that we will know what he suffered on our behalf in that winepress. But, as a prophet of God, Abinadi also testified that even the redemption of Christ cannot overpower human agency (see Mosiah 16:5). He has trodden “the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God,” but we must let him take out of our hand the cup of trembling. We must let go of the cup of wrath and accept instead the blood of the covenant.

If we do not choose faith, repentance, and making and keeping covenants, we are instead choosing to persist in our “own carnal nature, and [go] on in the ways of sin and rebellion against God.” Of those who make this choice, Abinadi warns that they “[remain] in [their] fallen state and the devil hath all power over [them]. Therefore [they are] as though there was no redemption made, being an enemy to God; and also is the devil an enemy to God” (Mosiah 16:5). Perhaps this is why judgment imagery is interwoven with the imagery of Christ treading the winepress alone. How we respond to his suffering on our behalf becomes our judgment. Without choosing to receive his gift with our faith and repentance, coming unto him on the covenant path, we will someday know that he redeemed us, but we did not want to be redeemed. He offers to take away the cup of wrath and replace it with the cup of his blood, his life, his fullness. We decide. We will receive what we are willing to receive.

Notes

[1] Russell M. Nelson, “Why This Holy Land?,” Ensign, December 1989, 13.

[2] Joseph L. Townsend, “Reverently and Meekly Now,” in Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 185.